Abstract

With the world of business often criticised for contributing to social and environmental damage, addressing sustainability has become necessary for virtually all business models, including co-operatives. This article investigates ways in which worker co-operatives can contribute to a more sustainable world, using the conceptual lens of Doughnut Economics (DE). It places enterprises, as a supporting pillar of our economies, at the intersection between meeting social needs and operating within planetary boundaries. A descriptive multiple case study of six worker co-operatives in the UK indicates that these enterprises contribute to sustainability primarily by embodying a mission of fulfilling the needs of workers and their communities, rather than just aiming for financial gains. Worker co-operatives are enterprises with highly generative design traits, distributive of the wealth they generate, and to some degree regenerative by design. Their strengths lie in learning capacity and distributive values that contribute to social sustainability. The implications of the study are demonstrated in the use of the DE model for addressing sustainability in the studied worker co-operatives. This article contributes to the body of knowledge on sustainability in worker co-operatives as a relatively less researched form of co-operative organisation, employing DE as a holistic framework which so far has been seldom used in business research.

1. Introduction

“The business of business is business,” according to Milton Friedman (cited in [1] (p. 68)) in his influential neoliberal market philosophy of the 1970s, reinforcing the ultimate goal of companies as that of producing, selling, and maximising profit [2]. Today’s mainstream business model of the Investor-Owned Firm (IOF) operates according to this principle [1] (p. 191). An IOF is characterised by private ownership and management in the hands of investor–shareholders who supply the capital [3]. However, these owners are normally absent from the day-to-day running of the business [4] (p. 168). The management of an IOF typically follows the principle that a company’s primary aim is to maximise the shareholders’ returns of investments [1] (p. 189), [4] (p. 155), [2,5]. This neoliberal epistemology is criticised for prioritising the interests of shareholders, and for providing incentives to externalise social and environmental costs, contributing to, for example, income inequality and job insecurity [6].

In response to these criticisms, and to increasing demands from consumers for businesses to become more sustainable [7], the private sector has started to widen the definition of what constitutes a successful business, to incorporate social and environmental goals, alongside financial metrics. Sustainability has been interpreted in numerous, often contested ways (see, e.g., [8]), with a prevalent description based on meeting long-term environmental, social, and economic goals [9,10]. How one views the relationship, between these three spheres of sustainability, matters. Sustainable development discourse, for example, has long aligned with the figure of three separate overlapping circles, with ensuing variations based on different ways of problematising the separateness between the environment, society, and the economy [8]. The heterodox theory of Social Ecological Economics (SEE), on the other hand, interprets the three dimensions as nested circles, with the economy nested within, and thus subordinate to, the wider social-ecological system [11] (p. 120).

One way to consider sustainability in the world of business is to turn Milton Friedman’s position on its head, and redefine “the business of business” as that of contributing “to a thriving world” [1] (p. 233). This supports a widespread call from economists, scholars, and civil society alike to reimagine the economic system (see e.g., [12,13,14]). Similar to the SEE theory, Kate Raworth describes an economy that lies between a social foundation of human wellbeing and an ecological ceiling of planetary boundaries [1] (p. 44). She calls this ‘Doughnut Economics’ (hereafter DE, further detailed in the Section 3). Reimagining business, following this theory, would involve redefining companies with “a living purpose, rooted in regenerative and distributive design” [1] (p. 234). A regenerative business is designed to embrace biosphere stewardship, reconnecting nature’s cycles, and giving back to the living systems it belongs to [1] (p. 218). A distributive business is designed to distribute financial wealth and other value sources, including income, knowledge, time, and power, in an equitable way [1] (pp. 174–176).

1.1. Co-Operatives

Rethinking our economic systems requires a transformation of practices at different levels, including the firm, with alternative business models required to disrupt the hegemony of the profit-driven IOF. Co-operatives represent an alternative form of organisation, and can be considered representative of alternative economic theories like the SEE, the Co-operative Economy, or the Social and Solidarity Economy. They can play a significant part in “reimaging and reconfiguring the economy as a whole as well as bringing to the table alternative forms of governance” [15] (p. 592). The model is broadly characterised by equal ownership and decision-making power in the hands of its members [16], as opposed to the investors or shareholders [17]. According to the International Co-operative Alliance (ICA), which is an apex body representing co-operatives worldwide, “a co-operative is an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise” [18]. To this end, co-operatives worldwide share a set of values including democracy, equality, and solidarity, and a set of principles:

- Voluntary and open membership

- Democratic member control

- Member economic participation

- Autonomy and independence

- Education, training, and information

- Cooperation among co-operatives

- Concern for community.

Co-operatives can be classified in various ways [15], with one way based on the groups that make up their membership. According to Cato [19] (p. 109), the three main membership types are: consumer or retail co-operatives, producer co-operatives (groups of producers), and worker co-operatives (owned by the employees). Each of these member groups have different sets of needs, aims, and structures. This project focused on the worker co-operative, based on an interest in exploring the effects of governance for sustainability in worker-owned corporations (as opposed to those in the hands of traditional investor–shareholders). Worker co-operatives are enterprises owned and controlled by their workforce [20]. For a more comprehensive description, we refer to Pérotin’s [21] (p. 35) definition:

A worker co-operative is a firm in which all or most of the capital is owned by employees in the firm, whether individually or collectively; where all employees have equal access to membership regardless of their occupational group; and where each member has one vote, regardless of the allocation of any individually owned capital in the firm.

Worker co-operatives exhibit several characteristics that positively contribute to the pillars of sustainability, with a considerable body of literature focused particularly on isolated economic and social aspects. Research shows that worker co-operatives can preserve jobs in deteriorating market conditions better than other firms can [3,15,21], that they can foster higher levels of job satisfaction and employee wellbeing [21], and that they can promote income equality [22] by reducing wage differentials [6,23]. Employment security has been shown to be the main motivator for joining a worker co-operative [24], as opposed to income maximisation per member, as previously considered [25]. Additionally, worker co-operatives can contribute to development in their community, by directing some of their profits, or surplus, to community projects [15,26], and they can lead to their members’ increased engagement in society [19] (p. 117) and participation in political democracy [27]. On environmental sustainability in worker co-operatives, the literature is scarce. One study [28] posits that worker co-operatives can contribute to climate change mitigation, through their lower interest, than that of their IOF counterpart, in perpetual growth, which means lower energy and material use, and thus lower greenhouse gas emissions.

However, worker co-operatives are not immune to challenges that can impede their long-term sustainability, with some arguing that this model is destined to fail [29]. Most notably, they face market pressures that put them at risk of compromising their principles [16] and reverting to capitalist practices, following what is known as the degeneration theory [30]. Examples of degenerative practices include employing non-member workers, concentrating power in the hands of management, or prioritising growth and profit-seeking above member needs [22]. They are also not inherently regenerative [1] (p. 233)—meaning, for example, that a worker-owned enterprise can still operate according to linear, cradle-to-grave processes of extracting natural resources and turning them into products meant to be disposed of after a short life cycle. To what extent, then, can a worker co-operative prove a business model fit for a more sustainable economic system and society?

1.2. Problem Statement, Aim, and Research Question

In order to redesign our economies for a sustainable future, more research is required into existing enterprise models, like worker co-operatives, that could contribute to disrupting the IOF hegemony. Studies on worker co-operatives and sustainability are few and far between, usually focus on a limited number of social issues, and seldom adopt a multi-dimensional approach.

The aim of this article was to explain how worker co-operatives may represent a regenerative and distributive business model in line with Kate Raworth’s holistic Doughnut Economy framework (DE). DE has so far seldom been applied to business research; thus, we extended its scope, to exemplify how this framework could be used as an internal exercise for enterprises to measure themselves against, and as an external exercise for members of society—including researchers and individuals—to analyse the sustainability of enterprises. To this end, the study explored the following research question:

- -

- In what ways can worker co-operatives align with Doughnut Economy principles, and what would be the implications for the sustainability of this enterprise model?

The findings of the study are intended to contribute to the body of knowledge on worker co-operatives’ potential to implement sustainable practices, thereby contributing to a thriving society. In the subsequent sections of the article, we account for our approach, starting with the method and a conceptual framework. This is followed by an empirical background that serves as a context for understanding the results, presented together with an analytical discussion. The article addresses the research question, along with a discussion that leads to conclusions, where we return to the aim of the project.

2. Method

The approach taken by this study is reflected in two parts: a conceptual and a methodological account, in what Robson and McCartan [31] refer to as “real world research”, which refers to researching a phenomenon in its context, with ambitions to capture the ongoing processes. This study focused on the organisational aspects of sustainable development, where national and international institutional contexts serve as backdrops. An initial literature review paved the way for making conceptual choices and ascertaining methodological priorities, as well as providing an empirical context.

2.1. Case Study

This study employed a multiple-case study method. It combined two methods for data collection: interviews, and reviews of online company documentation. A case study can be built on various methods of data collection and analysis [32]; thus, it should be understood as a research strategy rather than a method. Yin [33] (p. 18) offers the following often-cited definition for case studies and their use in research:

A case study is an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident.

For this research project, the definition of a case study was based on a descriptive, multiple-case, holistic design, a study of six worker co-operatives in the UK. The choice of worker co-operatives in the UK is further explained in Section 4: ‘An Empirical Background Based on a Literature Review’. A holistic case study involves one unit of analysis, and is grounded in a thorough understanding of the case through narrative descriptions. A descriptive case study uses a “reference theory or model that directs data collection and case description” [34] (p. 12). In this study, the reference theory in question was based on the DE framework (presented in Section 3: ‘A Conceptual Framework’), with a focus on the organisational aspects of sustainability in business.

A selection of case units was made from the worker co-operatives listed by Co-operatives UK [35] in the sixteenth and most recent edition of their ‘Organisation Data’ spreadsheet. The websites of the 379 currently trading worker co-operatives were mapped, checking for available information on three criteria: 1. co-operative identity; 2. sustainability agenda; and 3. annual reports and financial documents. When financial information was not available via a company’s website, the ‘Economic Data’ spreadsheet from Co-operatives UK (2020) was also consulted. From the co-operatives with some published information or policies relating to these three points, a selection was made, comprising different industries and different membership sizes, which were approached as potential case studies. The selection of case studies also aimed at covering different industries and corporate sizes. The final choice was based on the level of interest from the contacted representative of the co-operative. Six representatives of co-operatives agreed to be part of the research via an interview (by videocall or by email), and these co-operatives formed the basis of the study’s empirical data.

A case study protocol was developed, to guide the process of data collection. A set of protocol questions, inspired by Wilson and Post [2], was established for interviews and document review. The detailed case study protocol can be reviewed in Preluca [36] (p. 17).

2.2. Data Collection

The study employed two methods of data collection: semi-structured interviews with a respondent from each of the six co-operatives, and reviewing company documentation, either publicly available or as provided by the co-operative. Interviews provide a rich source of evidence in a case study research strategy, as case studies are usually concerned with “human affairs or behavioural events” [33] (p. 108). In this project, interviews with one worker–member from each business represented the main source of case study information. Five interviews were conducted by videocall, and lasted between 60 and 80 min, focusing on the case study protocol in a semi-structured format. One additional interview was done by email, with the respondent answering a set of pre-defined open questions.

Interview data were supplemented with information from each co-operative’s website, and from any relevant document and policy addressing the co-operative’s mission, structure, or sustainability initiatives (either publicly available or provided by the co-operatives). Some of these materials represented what De Massis and Katlar [37] (p. 19) call “more objective factual information,” and could be useful in combination with more interpretative data, like semi-structured interviews, for understanding organisational processes.

2.3. Data Analysis

The conceptual framework was based on the work of Raworth [1], DEAL [38], and Kelly [4]. The DE served as the structural support both for the data collection and the analysis of the cases. In order to sort, display, and analyse the data sets, we turned to the thematic analysis, specifically the template approach, as outlined by Crabtree and Miller [39] (1999). This approach involves “coding a large volume of text so that segments about an identified topic (the codes) can be assembled in one place to complete the interpretative process” [39] (p. 166). The initial template was developed, a priori, i.e., with codes based on the research questions and the theoretical framework (following the case study protocol). Further categories were added as and when the data showed evidence of emerging themes not covered by the a priori codes [36] (p. 21).

With the analytical template in hand, we proceeded to code and analyse the data for each case study, as part of a within-case analysis. This step involved descriptive write-ups of each case study, with descriptions central to generating insight [40]. A cross-case analysis was then performed, to identify potential similarities and differences between the co-operatives, as well as emerging patterns based on the proposed DE framework. Cross-case patterns rely on argumentative interpretation rather than quantitative metrics [33] (p. 160), a characteristic that relates to the overall interpretivist philosophical tradition adopted by the study. We focused on the cross-case analysis, with the within-case vignettes available in [36] (pp. 26–37).

2.4. Quality Assurance

Achieving research quality is accounted for in terms of validity and reliability (Table 1). Scrutiny of case study method [41] paves the way for procedures that reflect methodological reflection [42].

Table 1.

Techniques for establishing validity and reliability in case studies (based on [42] (pp. 78–79), with modifications).

3. A Conceptual Framework

A theoretical framework, based on Raworth’s [1] Doughnut Economy (DE) concept, was deemed pertinent for a study of business sustainability, given its foundation in Social Ecological Economics, (SEE), where economy (and thus business) is embedded in a wider social–ecological system [11]. Rejecting the neoclassical economics assumption that infinite economic growth is possible, even necessary for a healthy economy [1] (p. 32), SEE is formulated around the fulfilment of every person’s needs within the ecological limits of our planet [11] (p. 120).

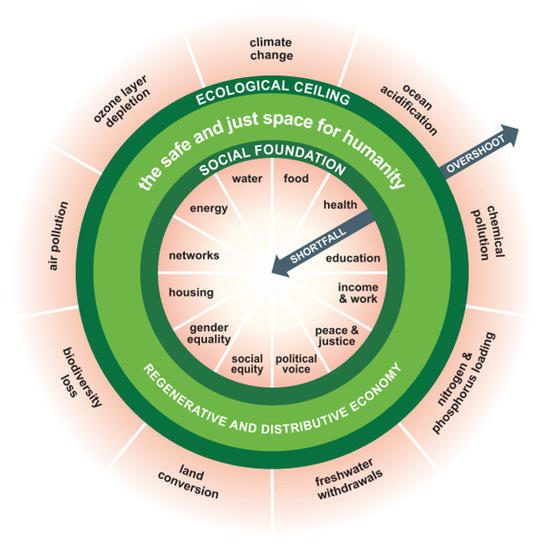

Following the principles of SEE, Kate Raworth’s DE is a vision of prosperity for humanity within the means of the planet (Figure 1). In the middle of the doughnut lies the social foundation of human wellbeing, comprising the basics of life, which no one should fall short on. They are crowdsourced from the social targets of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a set of global development goals adopted by all UN member states in 2015, with the ambition of achieving them by 2030 (United Nations, [43], for the 17 goals and their 169 targets). The outer ring denotes the ecological ceiling which humanity cannot overshoot, made up of the nine planetary boundaries—first introduced by a team of systems thinkers led by Rockström in 2009, and reviewed in 2015 [44]—considered essential to the functioning of Earth’s supporting systems. Between the two rings lies “the ecologically safe and just space in which humanity can thrive” [1] (p. 295), and it is this space that economic systems should aim for.

Figure 1.

The Doughnut of social and planetary boundaries (Kate Raworth and Christian Guthier, CC-BY-SA 4.0).

A framework on how to apply the model to the world of business is yet to be formulated. The Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL), a platform co-founded by Kate Raworth that works to put DE principles into practice, discusses the risk of co-opting the concept in the field of business, which would discredit it and undermine its transformative ambitions (DEAL, n/d). As a result, a policy on engaging business with the Doughnut is still in the making. Meanwhile, DEAL [38] has formulated three essential elements for enterprises interested in adopting a DE approach. These three elements, listed below, from DEAL [38], serve as a base for our conceptual framework.

- What is the mission of the enterprise? (DEAL [38] refers to this question as “Embracing the Doughnut as the 21st century goal”). The first directive of the DE theory requires changing the goal of the economic system (and, by extension, of business), from measuring progress based on economic growth, to meeting the human rights of every person within the means of the planet [1] (p. 25). Embracing the Doughnut as the goal of an enterprise would, in this project, mean asking whether its mission and business procedures are helping to bring humanity to a safe and just space in which everyone can thrive, or whether it is leading to transgressions of either the social or ecological boundaries.

- What are the enterprise design traits that support its mission? (DEAL [38] refers to this question as “Aligning the design traits of the business itself, through its Purpose, Networks, Governance, Ownership and Finance.”) In the project, it refers to analysing how a business is designed around its mission. Raworth draws on the framework of the generative enterprise proposed by Kelly [4]. A generative enterprise is based on the five design patterns presented in Table 2 [4].

Table 2.

Patterns in a regenerative enterprise [4] (pp. 153–206).

Table 2.

Patterns in a regenerative enterprise [4] (pp. 153–206).

| Theme for Pattern | Interpretation of the Theme | Empirical Key Questions to Support the Theme |

|---|---|---|

| Living purpose | At the core of a generative enterprise lies its living purpose, i.e., adopting a mission beyond financial returns: that of being of service to the community [4] (p. 153). Here, we will understand ‘community’ to include both social and environmental structures, similarly to ICA’s formulation of the seventh co-operative principle [18]. | What is the firm’s mission? How is it implemented—both explicitly, but also implicitly, in the way the firm is designed? |

| Rooted membership | Kelly [4] (p. 167) defines rooted membership as ownership in living hands, i.e., the hands of stakeholders closely related to the operations of the enterprise, rather than absent members disconnected from the life of the enterprise. |

|

| Mission-controlled governance | In a generative enterprise, governing control is kept in the hands of those concerned with its mission [4] (p. 182). They govern with a long-term view, ensuring the company’s legacy and mission are not for sale with new rounds of owners or managers. |

|

| Stakeholder finance | A generative finance design implies re-routing capital into human hands rather than distant investors [4] (p. 197). |

|

| Ethical networks | Ethical networks represent a design pattern outside the company itself; they are made up of the social and ecological communities that the firm belongs to [4] (p. 206). |

|

Kelly [4] (p. 14) notes that not every ownership model integrates all five design patterns (Table 2), but that the more generative patterns used, the more effective the design of the business will be. Therefore, one can conceptualise generative enterprises along a spectrum, rather than through binary labels of generative or non-generative.

- 3.

- How does the enterprise aim to be regenerative and distributive by design? Businesses need to be distributive by design, i.e., sharing value – from materials and energy to knowledge and income – equitably among those who help to create it and use it [1] (p. 176). A distributive design implies a redistribution both of income and of the wealth sources that help to generate income [1] (p. 205). Examples of this principle in practice include businesses owned by employees, those adopting living wages, and ethical supply chains, or those committed to paying a fair tax. This principle opposes the centralisation of value and wealth in the hands of a small proportion of top-level employees, with the aim of reducing inequality from the core of a business.

Businesses need to be regenerative by design, i.e., working with and within the cycles of the living world [1] (p. 218). One element of a more regenerative economy is a circular or cyclical design [1] (p. 220). Following circular economy theory, this circularity implies three principles: designing out waste and pollution, keeping materials and products in use and in the economy, and regenerating natural systems [45]. A regenerative design opposes the extractive design of linear business models, which are focused on extracting financial wealth and maximising profits.

The DE framework has certain limitations when applied to society at large, including the challenge that no country is currently meeting all social needs without transgressing any ecological boundary [46], and the impossibility of perfect material circularity as needed in a regenerative economy [47], and thus limitations to the concept of the circular economy. Furthermore, the framework’s intended universality comes with blind spots for specific local needs and boundaries. In the business field, the framework is in its early stages of application and reiteration, awaiting solid research to show if and how it can be used by organisations in a constructive manner. We therefore find it all the more suitable to utilise this framework for valuable lessons from one enterprise model.

4. An Empirical Background Based on a Literature Review

This study looked at the worker co-operative sector in the UK, a geographical choice based on the country’s rich history of co-operatives (e.g., [25]). The UK is widely regarded as the birthplace of the modern co-operative, following the model of the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society established in the English town of Rochdale in 1844. Notwithstanding this, the worker co-operative movement is now worldwide—from the Basque country, with its long-established and well-researched Mondragon worker co-operative (e.g., [24]), to the Worker Recuperated Enterprises (WREs) in Argentina [26].

Co-operatives of all sizes and structures in the UK are part of the trade body Co-operatives UK (CUK, CUOK) [48]. There are over 7000 co-operatives in the UK, operating across all industries, with over 14 million members (consumers, suppliers, workers, or a combination), employing more than 240,000 people [49] (pp. 2–3). Worker co-operatives are specifically represented in Co-operatives UK by the Worker Co-operative Council (WCC). There are around 500 worker co-operatives of different sizes, operating in various sectors [49] (p. 4), including retail, manufacturing, housing, education, and the media [35].

There is no designated co-operative legislation in the UK [49] (p. 2). Therefore, worker co-operatives can use any legal form—including companies, societies or partnerships—and self-define as a co-operative. A co-operative can choose to incorporate—that is, to adopt a legal identity for the organisation that is distinct from its members—or it can remain an unincorporated body, meaning it is treated as a group of people with individual and collective responsibility [50] (p. 13). The following information focuses on incorporated enterprises, since the six cases hereby studied are incorporated.

It is important to note the legal form a co-operative uses, because it indicates to others how the co-operative is funded, what it can do with the profits it generates, and how it interacts with its members [51]. Many co-operatives of all types choose to become societies, which are corporate bodies registered in England, Wales, and Scotland under the ‘Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014’ (CCBSA2014), and in Northern Ireland under the ‘Industrial and Provident Societies Act (Northern Ireland) 1969’ (IPSA(NI)1969). The six case studies were all from England, thus the information that follows draws on English sources. Societies registered in England are administered by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), an “independent, nongovernmental body that regulates the financial services industry in the UK” [50] (p. 31), which acts as the registrar of societies under the CCBSA2014. There are two legal forms that societies can adopt, i.e., a co-operative society and a community benefit society.

A different common form of incorporation is the Community Interest Company (CIC). CICs are registered with Companies House (i.e., the registrar of companies in the UK) but have two traits that differentiate them from other limited companies. They have a mandatory asset lock—meaning that their assets cannot be distributed among members or shareholders, but are passed onto charitable organisations or other asset-locked enterprises—and they must pass a test demonstrating community interest [50] (p. 26). The two forms of incorporation adopted by the enterprises studied are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of the key features of the two legal forms adopted by the co-operatives in the present study (based on [50,51]).

Table 3 highlights the two legal forms adopted by the six worker co-operatives, with different implications for how they can be owned, managed, and financed. Other possible legal forms for co-operatives can be found in [50,51], and are summarized in [36] (p. 25).

5. Results

This section begins with a brief factual summary of the six worker co-operatives included in the research (Table 4). We then move on to the cross-case analysis, that highlights commonalities and differences between the six cases (based on a preceding within-case analysis found in [36] (pp. 26–37)), and to a discussion of these findings in relation to the research question and previous literature, following the three theoretical components outlined in the DE framework.

Table 4.

General information on the six worker co-operatives included in the project.

The six co-operatives were purposefully chosen from different industries, locations, and sizes. Although co-operatives can adopt a wide variety of legal forms, most of the worker co-operatives sampled were co-operative societies, a common form of incorporation since CCBSA2014 was passed in 2014. The difference between number of members and total number of staff presented in the table above indicates which co-operatives employed non-member staff to add to their workforce. The six cases were analysed by following the three elements introduced by DEAL, as requisites for enterprises aiming to operate according to DE principles (mission-oriented, generative enterprise design traits, and distributive and regenerative by design).

5.1. The Mission of the Co-operative

The first directive for businesses to align with the DE concept is to be guided by a core mission of contributing to a thriving world [38]. The co-operatives had different ways of defining their mission, though one common thread was identified: aiming to create purposeful work that provided employees with decent livelihoods and a workplace that cared for their wellbeing. Outlandish stated its values to be “useful, meaningful work” and developing a structure that “maximises worker freedom, support and effectiveness.” Bristol Bike Project (BBP) was working towards an “inclusive, non-judgemental, vibrant and supportive environment” for all its volunteers and users. Co-operative Assistance Network Ltd. (CAN) was aiming to be “a good employer and an active democracy”. Leeds Bread Co-op (LBC) was seeking to build an “ethical and enjoyable workplace”. Calverts was aiming to carry out “decent work, i.e., interesting and work that has value.” Interwoven with the aim of caring for the workers were sustainable business ambitions, either in the sense of ensuring business continuity through delivering quality work and retaining customers (Calverts, Outlandish), or by being a fine example of a sustainable and responsible worker co-operative (Essential, CAN, LBC).

Most of the co-operatives were coupling internal-facing goals with an external-facing vision of contributing to the wellbeing of their communities. Essential’s mission was focused on driving sustainability in the food and retail industries, and making “a positive impact for people and planet.” For LBC, the Leeds part of their name referred to being a responsible member of their local community. BBP’s mission was rooted in empowering people, democratising knowledge on bicycles, and caring for the environment. CAN was on a quest to develop the common ownership movement, and to promote democracy and co-operation in society at large.

There were also some aspirational or revolutionary ideals coming through, yet all six co-operatives were well-rooted in the reality of having to meet their business needs (alongside striving to meet wider community needs) and work with achievable expectations. For example, costs might still dictate what suppliers a co-operative used, taking priority over environmental considerations; however, the reason behind this prioritisation was not to increase profits and returns for the member-owners—which would qualify as an example of degeneration into capitalist practices [22]—but, rather, to make sensible business decisions, maintain customers, create a pot of financial reserves, and ensure the continuity of the co-operative.

The motivation to work in a worker co-operative is also considered in this section, as it links the mission of the co-operatives with that of the co-operators. Most of the co-operative representatives discussed workplace democracy values as strong incentives. In the case studies, this involved:

- ◦

- giving workers control and decision-making power over their own work (Outlandish, LBC) and over the direction of the co-operative (BBP);

- ◦

- participating in decision-making (Calverts); individual autonomy (BBP), and self-responsibility (LBC);

- ◦

- sharing of power and responsibility among the members (Calverts).

Calverts was the only co-operative to indicate (good) wages as an incentive, with both Calverts and BBP mentioning the satisfaction of sharing the fruits of the labour with fellow workers and/or the community, rather than having external shareholders profit from their work.

Employment security was a key motivator, as found in other studies (e.g., [24]); however, it was not just any employment, but rather employment that was meaningful, interesting, ethical, and aligned with co-operative and democratic values (for most, but not all employees, as most of the co-operatives noted). It can be argued that this type of work contributes to the workers’ wellbeing, and can foster intrinsic motivation, i.e., meaning not related to income, supporting previous literature findings [21]. A good wage was in fact mentioned by only one out of the six co-operatives as one of the reasons to work in the co-operative. Income maximisation per member—what Craig and Pencavel [25] gathered from earlier studies to be the main incentive for workers—was not once mentioned; on the contrary, most of the co-operatives studied did not prioritise profit-sharing among members (e.g., “None of us at Outlandish really want to get rich and retire at 35, none of us have two houses, that’s not the kind of lifestyle that any of us have individually chosen”). This heightened intrinsic motivation could be linked to strong feelings of investment in the co-operative, that some interviewees expressed; they were in it for the long haul, and thus likely to set long-term goals and protect the co-operative’s mission. Some of the co-operatives had different levels of engagement with participatory processes among their membership, with some members more interested in getting their job done, than in co-operative organisational aspects. This fact is discussed primarily as an observation of individual choice of involvement, rather than as an organisational challenge.

Lastly, some of the respondents seemed, in one way or another, politically motivated to work in a worker co-operative. Essential believed this model to be an “alternative way of being,”; CAN saw themselves as “revolutionists here to change the world […] counter-cultural […] co-operators in a capitalist world,” LBC thought that the values of democracy at work were “so fundamental on a political level.” The interviewees from Outlandish jokingly referred to themselves and other members as “frustrated activists, where we can’t get paid to be an activist so we’re doing it through our job.” Working in a worker co-operative appeared to be almost an act of deliberate rebellion against mainstream business, with the interviewees displaying a strong feeling of pride in their work and in their co-operative model. Feelings of pride, belonging, and dedication, could prove a differentiator between worker co-operatives and IOFs or other business models. These differences have implications for how companies set their missions, and how their missions are then translated into behaviours.

5.2. What Are the Enterprise Design Traits That Support a Co-Operative’s Mission?

For a business to align with DE principles, it must align as closely as possible with what Kelly [4] refers to as the five design patterns of a generative enterprise: Living Purpose (discussed above under Mission); Rooted Membership; Mission-controlled Governance; Stakeholder Finance; and Ethical Networks.

An overarching observation on the worker co-operative model is that, at its core, it is a model emulating Kelly’s design patterns, starting with a Living Purpose. All six co-operatives had a mission that was clearly focused on meeting the needs of their members in a holistic sense (i.e., not just the need for a job and an income), as well as meeting wider societal needs in one way or another. The other four patterns flow towards the generative side of the spectrum as a result of this Living Purpose, as we illustrate below.

5.2.1. Membership

Membership at the six co-operatives was voluntary, and extended to all employees who met certain conditions (generally: having completed a probation period; in specific cases: working sufficient hours or completing a training program), in accordance with the first co-operative principle of ‘Open and Voluntary Membership’. Most of the co-operatives (CAN, Essential, Outlandish, LBC) had both members and non-member workers, with the membership of one co-operative (BBP) comprising both staff and volunteers. Employing non-member staff could be seen as a sign of degeneration, as per Storey et al.’s [30] theory that a worker co-operative will degenerate into capitalist practices to survive competition. However, a more just interpretation would be that this practice was often temporary (i.e., to cover seasonal roles or a member’s absence), and therefore aligned with the principle of voluntary membership. Workers were always encouraged to become members; nevertheless, some chose not to, usually because they did not want additional responsibilities. Membership came with voting power and responsibility although, in some cases, non-members were invited to attend meetings, and could participate in decision-making within their teams.

Regarding financial contributions, in some of the co-operatives, new members were asked to contribute a nominal membership fee of £1, which corresponded to one’s voting share. Essential was an exception, requiring both a £1 voting share and a £500 loan contribution to the co-operative’s financial reserves pot, a historical policy now under review to be scrapped, as the co-operative now has financial stability.

5.2.2. Governance

An organisational pattern across all the co-operatives was the use of teams or departments that were, to a greater or lesser extent, responsible for their work and decision-making. Essential and BBP, as relatively large co-operatives (100 and 70 members, respectively), formed, in addition, a management committee/directors’ group, that was elected by the members and had overall responsibility for the business. For most of the co-operatives, the main decision-making forum was represented by General Meetings, where the entire membership was convened (most commonly, quarterly meetings—out of which, one was an Annual General Meeting (GM)). The exceptions were LBC, where meetings for all members happened fortnightly, and Outlandish, where meetings seemed to happen on an ad hoc basis. By relying on members’ participation in governing the business, the six co-operatives adhered to the second co-operative principle of Democratic Member Control.

The co-operatives used a variety of decision-making mechanisms. The most common (CAN, Outlandish, partly Calverts) was to follow principles of sociocracy, whereby the team was organised in several circles that practiced autonomy (i.e., could make decisions) over their area of work, and decisions were made by consent (i.e., when there were no objections to a proposal). LBC made decisions by consensus (i.e., when everyone agreed on a proposal) but showed interest in sociocratic methods. At BBP and Essential, major decisions were made by voting at General Meetings (GMs), either by a simple majority or, in specific cases, by a higher majority threshold. BBP stood out, with a unique mentality in regard to decision-making, i.e., they aimed to be agile, and were not committed to any one method of making decisions, so as to avoid power issues that might arise from some people being more skilled in a particular method than their colleagues.

One way of investigating whether the governance system used in a co-operative is driven by its mission, is to compare its aims with its metrics of performance. For the co-operatives where this information was available (CAN, LBC, BBP), the metrics seemed to be a combination of financial and non-financial, mostly in line with their missions. For example, CAN had developed a grid, with definitions of what it meant to be a co-operative, a socially and environmentally responsible company, and achieving business objectives, with annual targets measured and published in performance reports.

5.2.3. Finance

The fourth co-operative principle, on Autonomy and Independence, emerged as a significant pattern in the co-operatives’ financial policies. Most of them had, at times, made use of internal or external financing (from bank loans and government grants to co-operative financing and member loans), yet always ensured that the funds did not come with demands that would compromise their autonomy or co-operative values (for example, a loan would not come with any decision-making power). In times of financial difficulties, all six co-operatives had seen their members agree to take temporary pay cuts (in some cases, the amount was later paid back), with some also cutting back on staff benefits, and making use of available reserves.

Five of the six co-operatives were registered as co-operative societies, a legal form which implies that capital can be raised by issuing shares, but only to co-operative members, and that they are withdrawable at any time by the members. Several of the co-operatives had made use of this option, of raising capital from the members at one point or another. The sixth co-operative was incorporated as a CIC, meaning that it was a not-for-profit organisation that had to use its surplus for social aims; additionally, it had a mandatory asset lock: thus, in the event of a foreclosure, all assets were to be transferred to a charity or a similar asset-locked enterprise.

5.2.4. Networks

True to the sixth co-operative principle of Co-operation among Co-operatives, the six cases showed clear evidence of working with, and within, their co-operative community. Co-operation was manifested as: sharing knowledge, skills, advice, ideas and/or organisational best practices (all six); trading with other co-operatives (Essential, LBC, Calverts); participating in national worker co-operatives bodies (Calverts, Essential); setting up co-operative communities in their trade (Outlandish) or, in the case of CAN, literally existing to develop other co-operatives. Outlandish and BBP both mentioned that they co-operated with other businesses within their own trade, thus pointing to the value of co-operation over competition.

Some of the co-operatives also worked with, and within, their local communities, linking to their external-facing mission, as per the seventh co-operative principle of Concern for Community. BBP directly served the local neighbourhood through the services it produced; Calverts was active in a body of independent businesses and a local environmental campaign group; LBC supported organisations with bread donations; Outlandish ran a co-working project with the local council, to teach residents technical skills.

Lastly, some co-operatives discussed their relationship with their customer or supplier networks. Essential was adamant about supporting independent trade rather than supermarkets, and had long-established relationships with both their customers and their suppliers. Similarly, LBC saw their customer groups as a tight-knit community that shared their values. Calverts’ client base was heavily focused on the social, education, and arts sectors, with a historical reputation for working with community groups and charities in the local area.

The six co-operatives studied took the co-operative values and principles to heart, which translated into the way they were designed and run. From ensuring membership was open to all, and voluntary, to working closely with and learning from other co-operatives, to holding onto ideals of autonomy and independence, particularly in challenging financial situations, they either implicitly or explicitly adhered to these internationally recognised directives—as both guidance and as an accountability framework. Here lies a learning opportunity for other business models, to reflect on establishing similar charters to function as an internal moral compass.

6. Discussion—Distributive and Regenerative by Design

The final DE directive is for enterprises to be regenerative and distributive by design. An enterprise is distributive by design when the various types of wealth it generates (be it income, knowledge, power, or time) is shared in an equitable manner among those who helped create it, those who use it, and those who are impacted by it [1]. A regenerative business is designed to work with and within nature’s cycles, following a circular design that keeps materials and products in use, minimises waste and pollution, and restores the living systems it resides in [1].

6.1. Distributive by Design

There were several strands through which the co-operatives proved to be distributive by design. Firstly, they distributed financial wealth internally, through wages that, as a minimum requirement, met the Living Wage Foundation standards, and which were often flat or with a low ratio between highest and lowest paid, thus contributing to reducing income inequality (as also observed by Parker [6] and Wren [23]). Where addressed, the co-operatives had different views on whether their salaries were good or sufficient, yet the idea was prevalent that wages were not a main driver.

Financial surplus, when available, was used in different combinations at the six co-operatives. Most frequently, part of the profits was retained as reserves, to carry the business through periods of low revenues, with financial crises in some cases proving significant for starting a reserve policy (e.g., Essential, after the 2008 crisis). Profit-sharing among members, in the forms of salary increases and/or bonuses, was used in some cases (Outlandish, Calverts, Essential), and was rare in others (CAN, BBP). The use of surplus, for purposes other than benefitting the co-operative and its workers, was common, e.g., supporting other co-operatives or community programmes; this reflected previous findings from Cheney et al. [15] and Vieta [26].

Another strand of wealth distribution was based on sharing knowledge with fellow co-operators, and with society in general, as well as learning from other co-operatives’ expertise, an idea less reflected in previous literature. Co-operatives shared know-how with other co-operatives, and learnt from each other’s best practices, including within their own industries, which was indicative of the role of co-operation over competition (although it is worth noting that relationships of direct competition were not addressed). Notably, CAN was explicitly open source, freely sharing tools with their users, and policy templates with other organisations, based on their vision of seeing “more property in common ownership”, including intellectual property. Some co-operatives also shared their expertise with their local community, as an act of empowering people (e.g., BBP taught bicycle maintenance skills to local people, to help them be independent; Outlandish taught people technical skills, to help improve their quality of life). This pattern of knowledge-sharing could be linked to the fifth and sixth co-operative principles, which require co-operatives to engage in training and development, and to support the work of other co-operatives, in order to strengthen the co-operative movement.

A theme that emerged inductively, in the data from several co-operatives, was poor diversity in their membership group. CAN, BBP, Outlandish, and LBC all pointed out that they were not very diverse, or not diverse enough, although some of them had a diversity policy in place. It can be posited that this issue means that co-operative wealth in all its forms is not equitably distributed in society, benefitting some groups more than others. Dedicated studies are needed on why the co-operative movement is lacking diversity, what the implications are for a business (e.g., one co-operative noted that diversity was essential to innovation), and potential ways of tackling this challenge.

Outlandish brought up a related point, concerning power dynamics among its workforce. The co-operative representative openly discussed the challenge some of the members had, of letting go of their position of power, at the same time as other members struggled to take power or to participate as required in a democratic organisation. This made for a surprising challenge, given the nature of a co-operative’s participatory model. Co-operatives can be easily idealised as being equal or flat structures, giving everyone the same voice, in terms of power and responsibility; however, worker co-operatives do not exist in a bubble: the power dynamics that exist in society at large can be replicated, even within a democratic organisation. Thus, it can be posited that what Johanisova and Wolf [16] referred to as the transition from power imbalances to democratic decision-making—as a characteristic of economic democracy—is exactly that: a transition, and thereby a process that takes time and effort, and begins with the recognition of where power imbalances lie in the first place.

Perhaps less explicitly, worker co-operatives are distributive of democratic practices and skills in the wider society, with implications for the strength of democracy as an institution. Our results show that people often learn to be engaged and to participate in running their co-operative, and through enhancing their participatory skills they can become more engaged with happenings in society at large. Some members expressed political motivations for joining their co-operative (in the sense of making a difference in the world), yet this was not a requirement, nor was it common for new workers. What was observed in some cases, however, was that some members became more political once they had experienced democratic principles and participatory processes at work, which they then applied to matters outside of work. This benefit of advancing democracy in society reflects previous findings by Cato [19] and Rothschild [27]. Further studies could investigate the correlation between the presence of a co-operative economy and the strength of democracy at local or national level.

6.2. Regenerative by Design

The explicit way in which the worker co-operatives that we studied aligned with regenerative principles, was through the products or services they sold, supplemented by some circularity initiatives in their business operations. BBP had a business model based on circularity at its core, by working to redirect functional bicycles from the landfill (thus also avoiding waste), as well as teaching people how to care for and maintain their bicycles. Essential contributed to regeneration and circularity through the products that they sold: for example, a large amount of their product range came with organic and/or Fairtrade certification, and was never genetically modified—all indicative of agricultural practices that aimed to avoid exploitation of resources and of people. Similarly, Calverts embedded circularity in how it sourced and produced its print products. On a smaller scale, most of the co-operatives had at least some circular ambitions, including: using renewable energy providers (Essential); minimising pollution and resource use (LBC, Calverts); and working with environmentally certified suppliers, where possible (Calverts).

Waste in one form or another was relevant to all six co-operatives, yet had only been addressed briefly, and in certain cases. LBC had solid ecological aims, including minimising waste, pollution, and resource use; however, the data were missing on whether and how these aims were achieved. Essential considered plastic packaging to be one of its most significant challenges, and had achieved some milestones in tackling plastic waste (e.g., discontinuing bottled water); however, it recognised that more work was needed on reducing food plastic packaging. BBP took what some might consider waste (bicycles and bicycle parts about to end up in the landfill), reintroduced them into circulation, and sourced products with less or no packaging, where possible. Calverts recycled some of its used printing parts into material for other industries, and used inks that enhanced the recyclability of paper. Other than these waste-related initiatives, waste management and disposal were not properly addressed, a potential focal point for future environmental work in the co-operatives. Designing out waste is a key component of a circular economy [45], with each co-operative having the opportunity to enhance its environmental contributions by streamlining its waste sources (e.g., food waste, material waste, e-waste).

A theme that emerged from the interviews was that working with suppliers could restrain the co-operatives’ environmental ambitions. One challenge was relying on suppliers that could not be controlled or influenced. For example, BBP was dependent on a few large suppliers that were often not providing the most environmentally friendly option, with smaller suppliers unable to cover all their needs. Essential had a strict supply chain policy—which arguably they could achieve, as an established business with strong buying power—yet they could not control their suppliers’ operations (e.g., the type of packaging they used). Another challenge was having to put in balance value/costs and ecological requirements. LBC would, for example, buy organic, when the cost of organic was not more than 50% higher than the non-organic alternative. Outlandish mentioned the trade-offs (price, convenience, reliability) between using two server suppliers that had different takes on environmental sustainability, with the ultimate decision being up to the client. Similarly, Calverts balanced out value, environmental impact, and other considerations in their sourcing decisions. A question for further consideration could be whether, and how, a worker co-operative could nurture environmental goals across its value chain.

Lastly, an observation pertaining to both regenerative and distributive principles was that most of the co-operatives did not have publicly available environmental or social reports. CAN is the only exception, publishing a yearly environmental report alongside its financial report (less regular social reporting). Calverts referred to environmental metrics by adhering to the ISO 14001 standards, an environmental certification for which they were getting audited regularly. Having policies focused on the environment was more common (Calverts, CAN, Essential) or, at least, organisational aims with an ecological focus (LBC, BBP). As Outlandish so eloquently put it, however, “the challenge is matching practice with policy”, so that the company’s behaviour matched its intention (be it a social, environmental, or co-operative intention). Measuring progress on environmental and social metrics could serve as an internal benchmark for co-operative performance, and help the co-operatives to make themselves more accountable to their communities.

7. Conclusions

The worker co-operatives’ representatives reflected, with pride and a high sense of community and responsibility, on their role in society:

“While you’re here you’re a caretaker, [the co-operative] is not yours, it’s commonly owned, it’s there forever. You come in and you look after it like looking after a garden, you keep the soil good, you eat well. When you leave the garden, that’s it, bye bye.”(Essential member)

“We are counter cultural. We are co-operators in a capitalist world”(CAN member)

This article has, as a broad starting point, the call to rethink one of the structures that supports our current mainstream economic system: the ubiquity of the IOF as the primary form of economic organisation. The IOF is not the sole form of organisation we have available in our economies. Alternative models, such as co-operatives, have been around for centuries, and are globally widespread: at least 12% of all people worldwide are members of co-operatives [52]. This study set about asking in what ways a worker co-operative could be a model better fitted to a sustainable future; it was conceptualised as aligning with Kate Raworth’s DE framework of a regenerative and distributive enterprise. Specifically, the study asked, “In what ways can worker co-operatives align with Doughnut Economy principles, and what are some implications for the sustainability of this enterprise model?”. With the Doughnut in hand, it set about investigating how six worker co-operatives in the UK aligned with a regenerative and distributive mission, principles, and design traits.

7.1. Aligning with Doughnut Economics

The six worker co-operatives exemplified how a business can function when driven by a mission other than making private financial gains, with the values it holds most dearly being its focus on worker and community wellbeing. As both Raworth [1] and Kelly [4] have remarked, it is the purpose of an enterprise that dictates how its other design traits fall into place, and having a Living Purpose is “the single irreducibly necessary core of every generative enterprise” [4] (p. 153). For the six co-operatives studied, this translated into an embedded mission to create decent livelihoods in their communities, and to operate as sustainable, responsible, successful worker co-operatives with a long-term mindset, particularly with regard to socio-economic issues. In turn, this mission enabled Kelly’s [4] other design traits, that describe worker co-operatives as generative enterprises, including having Rooted Membership, Mission-controlled Governance, Stakeholder Finance, and Ethical Networks.

On upholding distributive and regenerative principles, what clearly transpired was that the six cases had numerous success stories to tell, yet they also revealed certain shortcomings. Worker co-operatives are almost by default a largely distributive structure, and these six cases were no exception—showing examples of being distributive, particularly of financial wealth, knowledge, and skills. Where they were currently facing challenges—i.e., in widely lacking diversity, and in facing internal power issues—they discussed them with a strong sense of awareness and transparency, and they appeared willing to take steps towards taking responsibility. It was on regenerative principles that the six co-operatives notably fell short. Their focus was on minimising their environmental impact through various circular initiatives on different scales. It is essential to note, however, that for an enterprise to be truly regenerative, it must move past causing less damage into restoring living systems. This is what Raworth [1] (pp. 215–218) referred to as moving up the Corporate ‘To Do’ List, from “doing our fair share in making the switch to sustainability” or from “doing no harm” to “giving back to the living systems of which we are part”; it is in this area that worker co-operatives have most work to do internally, to align with the Doughnut.

7.2. Implications for Sustainability

In a literal sense, worker co-operatives can show that, despite the worker co-operative model being sometimes considered destined to fail [29], they are able to sustain themselves through waves of challenging times. Co-operative workers are committed to, and proud of, their co-operative; they welcome experimentation and continuous learning, and value flexibility and transparency in order to sustain their co-operative.

The co-operatives which we studied contributed to the three commonly conceptualised dimensions of sustainability, often in interconnected ways: for example, what the co-operatives referred to as providing “good” or “decent” employment relates to economic sustainability (through keeping wages in circulation in the economy, taxes, reduced unemployment, etc.), as well as to social sustainability (via worker wellbeing, as well as community wellbeing) and, in some measure, to environmental sustainability, when seen from the prism of the co-operatives’ environmental ambitions (which, as we noted, were currently relatively limited, in most cases). They could empower workers through participatory decision-making, they could reduce income inequality, and they could participate in the development of the local community and the widening of democratic practices.

The overarching implications of this enterprise model for sustainability show how a business founded in shared ownership can provide a decent life for employees and the community in which it resides, without jeopardising ecological health.

7.3. Continued Research

Further research could focus on the specific challenges observed in worker co-operatives, and their potential impact on the long-term sustainability of the enterprise model.

One example is the diversity challenge currently present in the co-operative movement (in the UK and potentially elsewhere), as noted in our findings. Previous literature points to another significant challenge for co-operatives in general: the issue of ‘opportunism’ or ‘free riding’ (see, e.g., [53]). Free riding can lead to a lack of active and informed participation in decision-making, which can impact on the survival of a co-operative in the market; it can also decrease member satisfaction [53]. The six interviewees did not point to opportunism issues as a significant challenge for their co-operatives, even though some did note differences in the levels of their members’ involvement in decision-making. One possible explanation was what Nilsson and Svendsen [53] refer to as the opposing explanations of free riding and trust, whereby a member’s lack of involvement did not necessarily mean they were shirking collective responsibilities, but that they might trust their fellow co-operators with a decision. Continued research could focus on worker co-operatives where free riding is specifically identified as a problem, checking for long-term impacts on the co-operative’s membership and governance, and the possible risk of its degeneration [30], and monitoring different types of solutions being put into practice.

Whether a worker co-operative can influence environmental sustainability across the value chain is another research avenue of interest, especially if looked at in comparison to an IOF. At a more macro-level, studies could explore whether the strength of democratic practices in organisations influences the strength of democracy at a local or national level. Based on the call to rethink our mainstream economic systems [see 12–14]—which this study attempts to contribute to—further research could explore the potential for an economic democracy system rooted in applying democratic principles at work, as exemplified by worker co-operatives and other democratic enterprises [16,54].

If the worker co-operative is proving to be an enterprise model well-designed for wellbeing and prosperity, future research could look into potential reasons why the model is what Booth called, in 1995, a “rarity” [55] (p. 229), such that nowadays it is still not a widespread form of economic organisation, or why it is more common in some countries—for example, Italy, Spain, France, and, to a lesser extent, the UK—but not in others. Finally, continued research may focus on how common ownership could become more common in business. A significant factor to include would be the history of co-operativism in different regions and political regimes across Europe and the world, and how this history influences current perceptions and practices of co-operative enterprises.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P., K.H. and C.M.-H.; Data curation, A.P.; Formal analysis, A.P.; Funding acquisition, C.M.-H.; Investigation, A.P.; Methodology, A.P. and K.H.; Project administration, A.P., K.H. and C.M.-H.; Resources, A.P.; Software, A.P.; Supervision, K.H.; Validation, A.P. and K.H.; Visualization, A.P.; Writing—original draft, A.P. and C.M.-H.; Writing—review & editing, A.P., K.H. and C.M.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent has been obtained from interviewed individuals, as part of the protocol in this kind of research at SLU.

Data Availability Statement

The data used from annual reports and corporate financial documents are all public documents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist; Penguin Random House: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, F.; Post, J.E. Business models for people, planet (& profits): Exploring the phenomena of social business, a market-based approach to social value creation. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 715–737. [Google Scholar]

- Pencavel, J.; Pistaferri, L.; Schivardi, F. Wages, Employment, and Capital in Capitalist and Worker-Owned Firms. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 2006, 60, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M. Owning Our Future: The Emerging Ownership Revolution, 1st ed.Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, N.P.; Straume, O.R. Are cooperatives more productive than investor-owned firms? Cross-industry evidence from Portugal. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2018, 89, 377–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M. Alternative enterprises, local economies, and social justice: Why smaller is still more beautiful. Management 2017, 20, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, R.E. Limits to labels: The role of eco-labels in the assessment of product sustainability and routes to sustainable consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, S. Mapping Sustainable Development as a Contested Concept. Local Environ. 2007, 12, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spash, C.L.; Asara, V. Ecological Economics. In Rethinking Economics: An Introduction to Pluralist Economics; Fischer, L., Hassel, J., Proctor, J.C., Uwakwe, D., Ward-Perkins, Z., Watson, C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, L.; Hassel, J.; Proctor, J.C.; Uwakwe, D.; Ward-Perkins, Z.; Watson, C. (Eds.) Rethinking Economics: An Introduction to Pluralist Economics; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Max-Neef, M. The World on a Collision Course and the Need for a New Economy. AMBIO 2010, 39, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleyers, G. Alter-Globalization Movement. In Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary; Kothari, A., Salleh, A., Escobar, A., Demaria, F., Acosta, A., Eds.; Tulika Books: New Delhi, India, 2019; pp. 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cheney, G.; Santa Cruz, I.; Peredo, A.M.; Nazareno, E. Worker cooperatives as an organizational alternative: Challenges, achievements and promise in business governance and ownership. Organization 2014, 21, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanisova, N.; Wolf, S. Economic democracy: A path for the future? Futures J. Policy Plan. Futures Stud. 2012, 44, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Co-Operatives UK. What Is a Co-Op. 2021. Available online: https://www.uk.coop/understanding-co-ops/what-co-op (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- ICA. Cooperative Identity, Values & Principles. 1995. Available online: https://www.ica.coop/en/cooperatives/cooperative-identity (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Cato, M.S. Co-Operative Economics. In Rethinking Economics: An Introduction to Pluralist Economics; Fischer, L., Hassel, J., Proctor, J.C., Uwakwe, D., Ward-Perkins, Z., Watson, C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cornforth, C. Co-operatives. In Concise Encyclopaedia of Participation and Co-Management; Széll, G., Ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pérotin, V. Invited Paper: Worker Cooperatives: Good, Sustainable Jobs in the Community. J. Entrep. Organ. Divers. 2013, 2, 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bretos, I.; Marcuello, C. Revisiting Globalization Challenges and Opportunities in the Development of Cooperatives: Revisiting Globalization Challenges and Opportunities for Cooperatives. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2017, 88, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wren, D. The culture of UK employee-owned worker cooperatives. Empl. Relat. 2020, 42, 761–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I. The ties that bind? Exploring the basic principles of worker-owned organizations in practice. Organization 2014, 21, 645–665. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, B.; Pencavel, J. The Objectives of Worker Cooperatives. J. Comp. Econ. 1993, 17, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieta, M. The Social Innovations of Autogestión in Argentina’s Worker-Recuperated Enterprises: Cooperatively Reorganizing Productive Life in Hard Times. Labor Stud. J. 2010, 35, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, J. Workers’ Cooperatives and Social Enterprise: A Forgotten Route to Social Equity and Democracy. Am. Behav. Sci. 2009, 52, 1023–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, R. Work time reduction and economic democracy as climate change mitigation strategies: Or why the climate needs a renewed labor movement. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2019, 9, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, G.K. Governing the Firm; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, J.; Basterretxea, I.; Salaman, G. Managing and resisting ‘degeneration’ in employee-owned businesses: A comparative study of two large retailers in Spain and the United Kingdom. Organization 2014, 21, 626–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, C.; McCartan, K. Real World Research: A Resource for Users of Social Research Methods in Applied Settings, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, R.W.; Tietje, O. Embedded Case Study Methods; Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Knowledge; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Co-Operatives UK. Open Data, 16th ed. 2020. Available online: https://www.uk.coop/resources/open-data (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Preluca, A. Doing Business in the Doughnut: The Sustainability of Worker Co-Operatives. Master’s Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2021. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1566878&dswid=-7467 (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- De Massis, A.; Kotlar, J. The case study method in family business research: Guidelines for qualitative scholarship. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEAL. When Business Meets the Doughnut. 2020. Available online: https://doughnuteconomics.org/tools-and-stories/44 (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Crabtree, B.F.; Miller, W.L. Doing Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvberg, B. Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riege, A.M. Validity and reliability tests in case study research: A literature review with “hands-on” applications for each research phase. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2003, 6, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Agenda. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Steffen, W.; Broadgate, W.; Deutsch, L.; Gaffney, O.; Ludwig, C. The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration; SAGE: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. What Is the Circular Economy? 2017. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/what-is-the-circular-economy (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- O’Neill, D.W.; Fanning, A.L.; Lamb, W.F.; Steinberger, J.K. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H. Review of Doughnut Economics, by Kate Raworth, Chelsea Green Publishers, 2017; Elsevier B.V: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Co-Operatives UK. About Us. 2021. Available online: https://www.uk.coop/about-us (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Co-Operatives UK. Worker Co-Op Code. 2015. Available online: https://www.uk.coop/resources/worker-co-op-code (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Co-Operatives UK. Simply Legal. 2017. Available online: https://www.uk.coop/resources/simply-legal (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Co-Operatives UK. 5.2 Choosing Your Legal form. 2021. Available online: https://www.uk.coop/start-new-co-op/start/choosing-your-legal-form (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- ICA. International Cooperative Alliance. 2018. Available online: https://www.ica.coop/en/about-us/international-cooperative-alliance (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Nilsson, J.; Svendsen, G.T. Free riding or trust? Why members (do not) monitor their co-operatives. J. Rural Coop. 2011, 39, 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ellerman, D.P. The Democratic Worker-Owned Firm: A New Model for the East and West; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, D.E. Economic democracy as an environmental measure. Ecol. Econ. 1995, 12, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).