The Interpretation of Quality in the Sustainability of Indonesian Traditional Weaving

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Indonesian Traditional Ikat Weaving SME Organizational Culture

2.2. Meaning of Quality in Organizational Culture

3. Methodology

Research Method

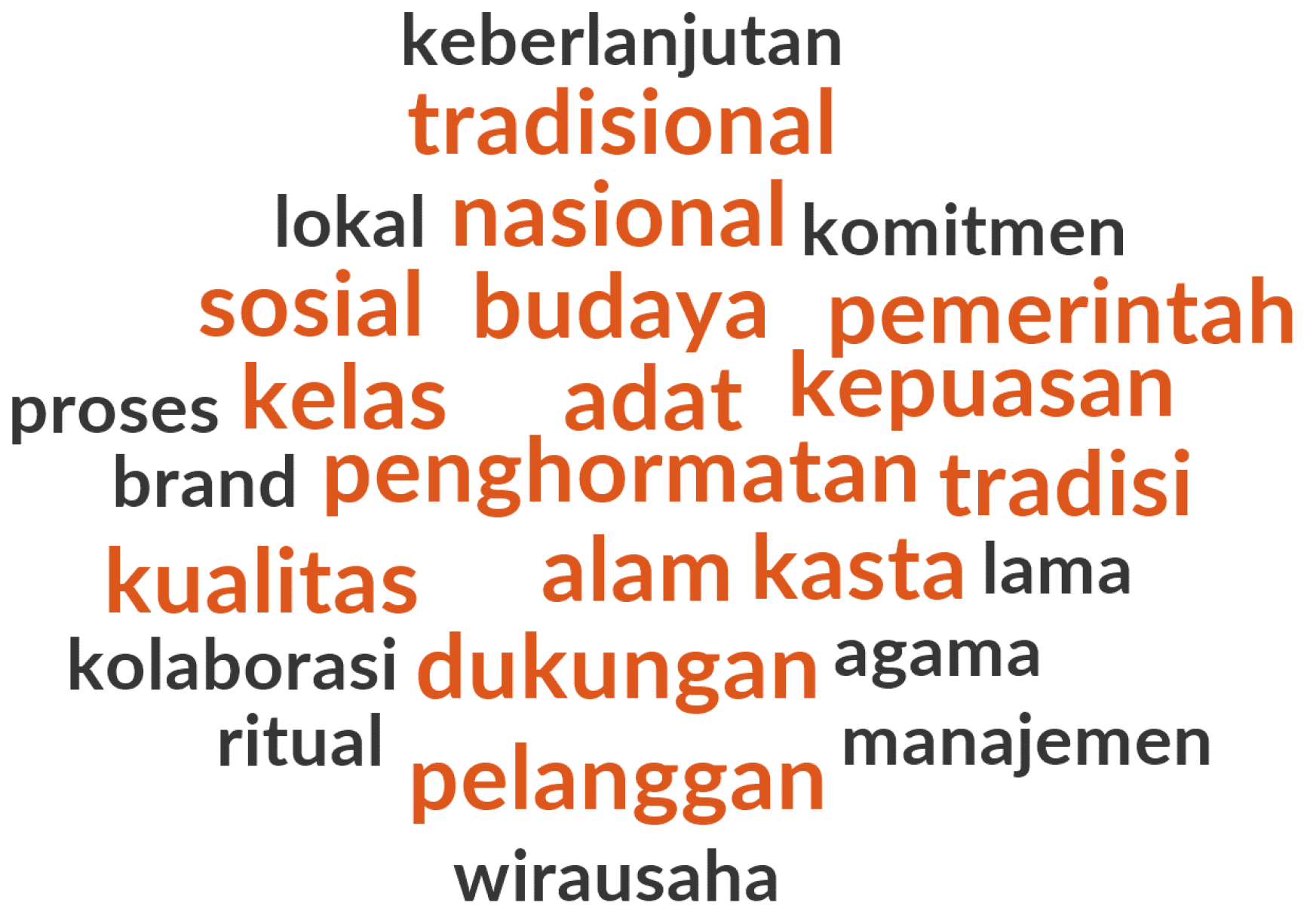

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Quality Is Commitment to Continual Process Improvement

“We create new designs that require a lot of experimentation. Experiments cost a lot of money, but once successful, the resulting product is reliable.”(Informant from Bali).

“We started to explore old motifs, which were originally just pictures of flora, then we gave animals or a combination of wayang and animal forms”(Informant from NTT).

5.2. Quality Is Honesty and Respect for Traditional Culture and Nature

“There is space and opportunity given to be creative. We are free to be creative, except in the type of ikat which already has certain standards. In our opinion, quality can basically be seen from the design, because each design is unique, has a specific history and materials.”(Informant from Bali).

5.3. Quality Is Reputation

“Producing superior, unique, and historically valuable products cannot be mass-produced because premium buyers highly value limited-produced products.”(Informant from Bali).

“Songket woven fabrics are produced manually, and the demand is still quite high because songket woven fabrics are used during religious ceremonies, harvests, deaths, and weddings. Although there are other substitutes, such as silk, cotton, and mixed products, we still maintain woven fabrics, which are traditional products”(Informant from Bali).

“Keep up with traditional products. I want to urge the government to provide copyright so that it is not easily plagiarized because many superior products are plagiarized by other people, both local and foreign people.”(Informant from Bali.)

“Getting the government’s recommendation to have IPR certification is not as easy as promised. The process of obtaining IPR is very burdensome in terms of costs, bureaucracy, and documentation of product variations in each production process”(Informant from Bali).

5.4. Quality Is Compliance with Standard Operating Procedure

“There are many aspects that must be met in creating woven fabrics of guaranteed quality. We must maintain the quality of raw materials, auxiliary materials, and weaving processes that are acceptable to the community at the regional, national, and international levels.”(Informant from Toraja.)

5.5. Quality Is HR Investment

“Weavers must be able to understand the wishes of buyers and be able to describe them in modified motifs. So, to improve their skills, weavers need to receive training from the Cooperative Service. To maintain the quality of woven fabrics, buyers as users also need to know how to maintain woven products. It takes a lot of socialization from the weaving cooperative to the community as users.”(Informant from Bali).

5.6. Quality Is Synergy

“If the government pays more attention, the craftsmen will definitely improve their quality. The government should intervene because each district has its own weaving craftsmen.”(Informant from NTT).

“We are greatly helped by the existence of exhibitions, for example, big events whose markets reach overseas.”

“Many women have started to like weaving. We find it very helpful when the local government establishes woven cloth as an official uniform that must be worn every certain day regularly. Woven clothing is also the formal uniform of government officials in attending formal events, thus showing the identity of the NTT region. This will be the easiest marketing tool”(Informant from NTT).

“We need support so that these affordable woven products can sell quickly. Therefore, government support is needed to accommodate this segmentation, including the provision of low-cost financing facilities and guarantees of intellectual rights for traditional weaving motifs”(Informant from Bali).

6. Implications

Building Organizational Culture through Quality in Weaving SMEs

7. Conclusions and Research Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ndou, V.; Schiuma, G.; Passiante, G. Towards a framework for measuring creative economy: Evidence from Balkan countries. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2019, 23, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elassy, N. The concepts of quality, quality assurance, and quality enhancement. Qual. Assur. Edu. 2015, 23, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundararajan, K. Cost-reduction and quality improvement using DMAIC in the SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Perf. Manag. 2019, 68, 1528–1540. [Google Scholar]

- Husband, S.; Mandal, P. A conceptual model for quality integrated management in small and medium size enterprises. Int. J. Qual. Rel. Manag. 1999, 16, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanzon, J.B.P.; Muhi, M.M. Significant factors to motivate small and medium enterprise (SME) construction firms in the Philippines to implement ISO9001:2008. Procedia Eng. 2017, 171, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaabi, K.A. Customers’ purchasing behavior toward home-based SME products: Evidence from UAE community. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2021, 16, 472–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L.; Lourenço, L. Factors that hinder quality improvement programs’ implementation in SME: Definition of a taxonomy. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2014, 21, 690–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D.; Reeves, K. How to build a quality management climate in a small to medium enterprise. An action research project. Intern. J. Lean Six Sigma 2021, 13, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G. Do SMEs need to strategize? Bus. Strategy Ser. 2011, 12, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthy, R. Nature of Qualitative Research. In Methodological Issues in Management Research: Advances, Challenges, and the Way Ahead; Subudhi, R.N., Mishra, S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; pp. 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, B.; González-Romá, V.; Ostroff, C.; West, M.A. Organizational climate and culture: Reflections on the history of the constructs in JAP. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Chatman, J.A.; Caldwell, D.F. People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 33, 487–561. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan, F.; Baird, K.; Munir, R. The association between organisational culture, CSR practices and organisational performance in an emerging economy. Meditari Account. Res. 2020, 28, 977–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifah, H.; Halim, H.A.; Ahmad, N.H.; Vafaei-Zadeh, A. Emanating the key factors of innovation performance: Leveraging on the innovation culture among SMEs in Malaysia. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2019, 13, 559–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alosani, M.S.; Yusoff, R.Z.; Alansi, A.M. The effect of six sigma on organizational performance: The mediating role of innovation culture. J. Adv. Res. Des. 2018, 47, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Aboramadan, M.; Albashiti, B.; Alharazin, H.; Zaidoune, S. Organizational culture, innovation, and performance: A study from a non-western context. J. Manag. Dev. 2020, 39, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumuk, Y.; Kurgun, H. The Role of Organizational Culture Types on Person-Organization Fit and Organizational Alienation Levels of Hotel Workers; Ruel, H., Lombarts, A., Eds.; Sustainable Hospitality Management; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; Volume 24, pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Azeem, M.; Ahmed, M.; Haider, S.; Sajjad, M. Expanding competitive advantage through organizational culture, knowledge sharing and organizational innovation. Tech. Soc. 2021, 66, 101635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yipa, J.A.; Levine, E.E.; Brooks, A.W.; Schweitzerd, M.E. Worry at work: How organizational culture promotes anxiety. Res. Org. Behav. 2020, 40, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-Espin, J.A.; Jiménez-Jiménez, D.; Martínez-Costa, M. Organizational culture for total quality management. Tot. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2013, 24, 678–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.J. TQM and organisational culture: How do they link? Tot. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2012, 23, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, X.; Robbins, T.L.; Fredendall, L.D. Mapping the critical links between organizational culture and TQM/Six Sigma practices. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 123, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albourini, F.; Al-Abdallah, G.M.; Abou-Moghli, A. Organizational culture and total quality management (TQM). Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 8, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, A.; Kurey, B. Creating a culture of quality. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2014, 92, 23–25. Available online: https://hbr.org/2014/04/creating-a-culture-of-quality (accessed on 24 September 2021). [PubMed]

- Cadden, T.; Marshall, D.; Cao, G. Opposites attract organisational culture and supply chain performance. Supply Chain Manag. 2013, 18, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafreshi, M.Z.; Pazargadi, M.; Abed Saeedi, Z. Nurses’ perspectives on quality of nursing care: A qualitative study in Iran. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Ass. 2007, 20, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solin, A.; Curry, A. Perceived quality: In search of a definition. TQM J. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kemenade, E.; Van der Vlegel-Brouwer, W. Integrated care: A definition from the perspective of the four quality paradigms. J. Integrated Care 2019, 27, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetteh, G.A.; Amoako-Gyampah, K.; Twumasi, J. Developing a quality assurance identity in a university: A grounded theory approach. Qual. Ass. Edu. 2021, 29, 238–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Chawla, V.; Tähtinen, J. Dimensions of e-return service quality: Conceptual refinement and directions for measurement. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutingi, M.; Chakraborty, A. Quality management practices in Namibian SMEs: An empirical investigation. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2021, 22, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanapathy, K.; Bin, C.S.; Zailani, S.; Aghapour, A.H. The impact of soft TQM and hard TQM on innovation performance: The moderating effect of organisational culture. Int. J. Prod. Qual. Manag. 2017, 20, 429–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Greenhalgh, T.; Westhorp, G.; Pawson, J.B.; Pawson, R. RAMESES publication standards: Meta-narrative reviews. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ferasso, M.; Takahashi, A.R.W.; Gimenez, F.A.P. Innovation ecosystems: A meta-synthesis. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2018, 10, 495–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morselli, D.; Marcelli, A.M. The role of qualitative research in Change Laboratory interventions. J. Workplace Learn. 2022, 34, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyumba, T.O.; Wilson, K.; Derrick, C.J.; Mukherjee, N. The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, V.G. Methodological Insights Theory development in qualitative management control: Revisiting the roles of triangulation and generalization. Acc. Aud. Account. J. 2021, 34, 451–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azrani, A.; Maulana, H.A. Strategi pengembangan industri kreatif kain tenun lejo sebauk pada masa pandemi COVID-19. J. Manaj. Dan Kewirausahaan. 2021, 6, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Waluyati, S.A.; Kurnisar; Sulkipani. Analisis upaya-upaya pengrajin tenun songket dalam mempertahankan kelangsungan usaha di Desa Sudimampir Kecamatan Indralaya Kabupaten Ogan Ilir. J. PROFIT Kaji. Pendidik. Ekon. Dan Ilmu Ekon. 2016, 3, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Nenengsih, A.S.E. Strategi pengembangan industri kerajinan sulaman/tenun Sumatra Barat berbasis sinergitas multi-stakeholders. Menara Ekonomi 2019, 3, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ro’ini, Y.K.; Prahastuti, E.; Rahayu, S.E.P. Upaya peningkatan kualitas tenun ikat Bandar Kediri. Prosiding Pend. Teknik Tata Boga Busana FT UNY 2021, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Atmoko, T.; Dharsono. Perkembangan ragam hias tenun ikat gedog Bandar Kidul Mojoroto Kota Kediri Jawa Timur. J. Seni Bud. 2015, 13, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Nisa, N.C.; Nadiroh. Studi kualitatif nilai-nilai ekofeminis pada komunitas kerajinan tenun di Desa Sukarara Kecamatan Jonggat, Lombok Tengah. J. Green Growth Dan Manaj. Ling. 2017, 6, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Firdaus, F. Eksistensi Tennung Walida (Gedogan) Kain Sutera di Desa Rumpia Kecamatan Majauleng Kabupaten Wajo. Equilibrium J. Pend. 2021, IX, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudirtha, I.G. Diversifikasi produk industri tenunan tradisional Bali menuju industri kreatif. Sem. Nas. Riset Inov. 2014, II, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar]

- Fauziyah; Suharto, H.A. Astuti, I.Y. IbM kelompok pengrajin tenun ikat khas Kediri. J. Dedikasi 2016, 13, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Naini, U.; Dangkua, S.; Naini, W. Kerajinan tenun tradisional Gorontalo. Jambura: J. Seni Dan Desain 2020, 1, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Samsir, S.; Nurwati, N. Pelestarian seni budaya melalui home industry tenun Samarinda: Perspektif Sejarah Islam. El-Buhuth 2018, 1, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismanto, H.; Tamrin, M.H.; Pebruary, S. Pendampingan Usaha Kecil dan Menengah Tenun Ikat Troso dalam peningkatan produktivitas dan kualitas produk kain. J. Pengab. Dan Pember. Masy. 2018, 2, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamiludin; Agustang, A.; Samad, S. Kerajinan Tenun pada Masyarakat Muna (Kasus Peranan Modal Manusia dan Modal Sosial Dalam Reproduksi Budaya Tenun di Kabupaten Muna). 2020. Available online: https://osf.io/4bksf/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Mustikasari, H.; Destiarm, A.H.; Sachari, A. Kajian terhadap kecenderungan aspek visual dalam perancangan produk mode berbasis Tenun Gedhog khas Tuban. KELUWIH J. Sains Dan Tek. 2020, 1, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, R.I.; Budiani, S.R. Analisis strategi pemasaran industri tenun di Desa Wisata Gamplong Kabupaten Sleman. Majalah Geo. Ind. 2018, 32, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telagawathi, N.L.W.S. Inovasi pemasaran dan penciptaan pasar kain Tenun Endek di Kabupaten Klungkung. Sem. Nas. Riset Inov. 2014, II, 875–890. [Google Scholar]

- Adnyani, N.K.S. Perlindungan hukum indikasi geografis terhadap kerajinan tradisional Tenun Grinsing Khas Tenganan. Sem. Nas. Pengabdian Masy. 2016, I, 223–235. [Google Scholar]

- Hidayah, S. Tradisi menenun pengrajin Bugis Pagatan di era globalisasi. BioKultur 2019, VIII, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Maulia, R. Wisata budaya dalam tradisi tenun di Kecamatan Mempura Kabupaten Siak. J. Online Mahasiswa Fak. I. Sos. Dan I. Pol. Univ. Riau. 2015, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ernawati, S. Strategi pengembangan umkm tenun untuk meningkatkan sosial ekonomi di Kota Bima. Proc. Sem. Nas. Ek. Dan Bis. 2021, I, 190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, M.I.; Williams, I.A.; Hammoud, M.S.; Dwyer, R.J. Strategies for implementing innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sust. Dev. 2020, 16, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’zungu, S.; Merrilees, B.; Miller, D. Strategic and operational perspectives of SME brand management: A Typology. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 943–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Rangarajan, K. Impact of policy initiatives and collaborative synergy on sustainability and business growth of Indian SMEs. Indian Growth Develop. Rev. 2020, 13, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Zhang, S. Institutional quality and internationalization of emerging market firms: Focusing on Chinese SMEs. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 92, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anning-Dorson, T. Organizational culture and leadership as antecedents to organizational flexibility: Implications for SME competitiveness. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 13, 1309–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Mutingi, M.; Vashishth, A. Quality management practices in SMEs: A comparative study between India and Namibia. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 26, 1499–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Literature Search Results | Main Categories | Initial Themes |

|---|---|---|

| Quality is the synergy of stakeholders |

| |

| Quality is respect for traditional culture and nature |

| |

| Quality is Commitment |

|

| Quality is reputation |

|

| Quality is in conformity with standard operating procedure. |

| |

| Quality is empowering education and training |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Semuel, H.; Mangoting, Y.; Hatane, S.E. The Interpretation of Quality in the Sustainability of Indonesian Traditional Weaving. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811344

Semuel H, Mangoting Y, Hatane SE. The Interpretation of Quality in the Sustainability of Indonesian Traditional Weaving. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811344

Chicago/Turabian StyleSemuel, Hatane, Yenni Mangoting, and Saarce Elsye Hatane. 2022. "The Interpretation of Quality in the Sustainability of Indonesian Traditional Weaving" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811344

APA StyleSemuel, H., Mangoting, Y., & Hatane, S. E. (2022). The Interpretation of Quality in the Sustainability of Indonesian Traditional Weaving. Sustainability, 14(18), 11344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811344