Abstract

Considering that the role of leadership is still essential for a corporate organization to grow and develop continuously, self-leadership based on a sense of ownership is emerging as the ideal leadership required of organizational members. However, despite the great efforts of academia in investigating the effectiveness of self-leadership in various industrial fields, prior literature on self-leadership in the context of sports center organizations seems to be limited. The objective of the present study was to examine the influence of sports center employees’ self-leadership on leader-member exchange (LMX) and organizational commitment and the mediation role of LMX in the relationship between self-leadership and organizational commitment. A total of 172 Korean sports center employees participated in the present study. The results indicated that sports center employees’ self-leadership significantly impacted LMX and organizational commitment, and LMX positively affected organizational commitment. Additionally, sports center employees’ LMX had an important partial mediation role in the relationship between self-leadership and organizational commitment. Consequently, the current study’s findings provide sports center organizations with practical implications for enhancing organizational effectiveness.

1. Introduction

Today’s industrial environment, represented by the emergence of an alternative knowledge system based on big data and the spread of individualism centered on quality of life, is facing more rapid changes than ever, and corporate competition is accelerating daily [1,2]. For organizations to survive and maintain a competitive advantage in this hypercompetitive environment, it is necessary to break away from traditional organizational management strategies and practice an alternative organizational management method that enables all members to participate and immerse themselves in the innovation process to strengthen the value chain [3]. As part of alternative organizational operations for sustainable growth, organizations have embraced various forms of leadership which is a crucial success factor for individual projects within the organizations [4]. However, the reality is that realizing effective leadership is becoming more difficult due to rapid changes in the business environment and the diversified characteristics of organizational members nowadays. Considering that the role of leadership is still important for a corporate organization to grow and develop continuously, especially self-leadership based on a sense of ownership is emerging as the ideal leadership required of organizational members [5].

Self-leadership is the concept of self-management breaking away from the leader-centered leadership paradigm in which the leader’s role leads the members to a higher position than the members’ organization. Self-leadership also emphasizes the cooperative relationship between leaders and organizational members to maximize the potential of members and achieve the organizational goals of sustainable growth and development [6,7]. Self-leadership is an action process in which the attitudes and behaviors of organizational members actively participate in the value creation process according to their motives and judgments, rather than relying solely on standard roles within the organization or instructions from superiors. In other words, self-leadership refers to improving work efficiency and organizational performance by inducing job enthusiasm and organizational commitment through self-motivation and self-control by all organization members, rather than recognizing it as a leader-centered corporate organization [8].

Self-leaders who have the attitude that they are the owners of a corporate organization are likely to develop psychological ownership of the organization in the process of performing their work [9]. Self-leadership has been widely studied as an important factor that positively affects organizational effectiveness, such as organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intention [10,11,12]. In particular, organizational commitment, which refers to the psychological bond employees have with their organizations, is considered a crucial end-product of self-leadership because employees are more likely to be productive and dedicated to their work when they feel a strong sense of belonging to their organizations [13]. Moreover, as self-leaders are evaluated as members who do their best in a given task and show productivity without detailed management from their supervisors, organizational members with strong self-leadership skills tend to build amicable relationships with colleagues and supervisors [3]. In fact, several previous studies have empirically identified self-leadership as an important factor that enhances the desirable relationship among members and positively affects organizational commitment, enhancing overall organizational effectiveness [1,3].

Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) is also recognized as one of the important factors affecting organizational commitment in today’s competitive business environment. From an LMX viewpoint, unlike the traditional leadership viewpoint, which focuses on the one-sided influence of an organizational leader on members, the leader of a working group establishes a close relationship with the members of the work unit [14]. In fact, LMX, which evolved from the vertical dyad linkage theory, focuses on the interaction between leaders and members [15]. LMX has been considered a crucial factor that increases organizational effectiveness in various industrial fields and has been proven to positively affect employees’ empowerment, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment [3]. Previous studies have reported that the higher the quality of LMX, the higher the organizational commitment and job satisfaction and the lower the turnover intention [15,16]. More importantly, LMX is suggested as a crucial mediator in the relationship between self-leadership and organizational effectiveness, such as organizational commitment and job satisfaction [3].

Meanwhile, an increase in corporate productivity and public interest in health has contributed to the rise in the population participating in physical activity and, in turn, the quantitative expansion of sports facilities [17]. In particular, a sports center is a sports facility that exhibits rapid quantitative expansion because the public can easily participate in sports activities regardless of time and place in a complex living area and acquire many exercise effects at a relatively low cost [18]. Another reason for the quantitative expansion of sports centers is that. In contrast, in the past, the role of sports centers was only to provide participants a place for physical training. Most sports centers nowadays provide systematic physical activity programs to customers based on professional exercise counseling and transform themselves into spaces where social interaction with others is easy [19]. Nevertheless, the quantitative increase of sports centers is accelerating competition within the sports center operating industry. For a sports center, the role of employees who communicate with customers face-to-face at service points is crucial to surviving in a competitive market environment. In particular, a leader’s leadership of a sports center organization influences the behavior of its members. As it determines the operational direction and job performance, it dramatically affects organizational effectiveness [3,20]. Consequently, a sports center that provides human services based on facility resources requires effective leadership and management innovation strategies to survive in a competitive business environment and pursue sustainable growth.

Numerous studies have been conducted on self-leadership and organizational effectiveness in various industrial fields. However, research on the mediating effect of LMX on the relationship between self-leadership and organizational commitment of sports center employees is relatively limited. Moreover, prior studies do not provide a sufficient explanation for whether LMX partially or fully mediated the relationship between self-leadership and organizational commitment of sports center employees. Suppose it can be empirically identified as to what level of mediating effect LMX has in the relationship between sports center employees’ self-leadership and organizational commitment. In that case, it can justify the enhancement of employees’ LMX to improve organizational commitment, thereby providing sports center managers with practical implications for developing effective managerial strategies. Therefore, the present study investigated the effects of self-leadership on organizational commitment among sports center employees and the mediating effect of LMX in the relationship between the relevant variables. Additionally, we developed the following research questions:

- Q1: Does self-leadership of sports center employees have a positive effect on LMX?

- Q2: Does self-leadership of sports center employees have a positive effect on organizational commitment?

- Q3: Does LMX of sport center employees have a positive effect on organizational commitment?

- Q4: Does LMX of sports center employees have a partial or full mediating effect on the relationship between self-leadership and organizational commitment?

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Self-Leadership and Organizational Effectiveness

For the past decades, sports organizations have emphasized organizational sustainability, which refers to allowing an organization to remain financially and socially sustainable, as key in managerial strategies [21]. Self-leadership is one of the internal marketing measures to respond flexibly to the rapidly changing business environment and is being emphasized as an essential factor for the sustainable growth of an organization. In particular, a self-leader develops psychological ownership in performing his or her task and shows an enterprising attitude toward solving the given task, and shows immersion and attachment to the organization [9]. In addition, self-leadership is an important prerequisite for forming a constructive and positive relationship between leaders and members and ultimately enhances organizational effectiveness [3,22]. Consequently, self-leaders increase job-solving efficiency by leading a given task themselves and contribute to organizational effectiveness by forming a high-quality relationship with leaders.

2.2. Self-Leadership and Leader-Member Exchange (LMX)

The importance of self-leadership is being emphasized as one of the internal marketing strategies of corporate organizations to respond flexibly to the rapidly changing business environment. Additionally, self-leadership is a process that enables organizational members to become self-leaders. It has the concept of leadership in which organizational members use behavioral and cognitive strategies to influence themselves [6]. Especially, self-leadership refers to the autonomous and responsible behaviors and attitudes that service organization employees must have to achieve customer satisfaction [11]. According to Manz [8], self-leadership consists of an action-oriented strategy, which means suppressing undesirable behaviors and enhancing successful performance through positive behaviors, a natural reward strategy related to the enjoyment of a given task, and a constructive through pattern strategy, which refers to the visualization of successful performance. Moreover, organizational members who effectively utilize self-leadership strategies have higher performance than those who do not, strongly immerse themselves in their tasks, and solve key problems correctly [23]. In addition, self-leadership plays a significant role in improving positive interaction between leaders and members through active participation in task activities of organizational members [24]. Son [3] reported that self-leadership has a significant effect on LMX and concluded that positive psychological energy generated from adopting self-leadership by organizational members not only forms positive relationships among the members but also contributes greatly to creating a positive organizational atmosphere. Therefore, the current study proposes the following hypothesis based on the findings of previous relevant studies:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Sports center employees’ self-leadership will have a positive effect on leader-member exchange (LMX).

2.3. Self-Leadership and Organizational Commitment

Organizational effectiveness refers to the degree to which the various resources the corporate organization possesses are effectively utilized [25]. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intention are the most frequently used indicators of organizational effectiveness [26]. In particular, organizational commitment is an employee’s willingness to devote his or her positive energy to all tasks. It can be enhanced when an employee feels empowered in job performance and forms amicable relationships with supervisors and co-workers [27]. Previous studies report that a self-leader who takes the initiative in their work develops a sense of psychological ownership in the task performance process and shows more unity, attachment, and activeness toward their jobs [9,28]. In this regard, Ha [11] investigated the results of self-leadership enhancement, and it was confirmed that self-leadership positively affected organizational commitment and justice. You and Lee [22] argued that self-leadership is an important predictor of organizational effectiveness, including organizational commitment and job satisfaction, and suggested that firms should provide learning and training programs for self-leadership for the employees to improve organizational effectiveness. Jin and Kim [29] also reported that self-leadership had significant effects on organizational commitment and job satisfaction but had a stronger effect on organizational commitment than job satisfaction. Based on the prior studies, the following hypothesis can be suggested:

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Sports center employees’ self-leadership will have a positive effect on organizational commitment.

2.4. Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) and Organizational Commitment

In corporate organizations, leaders and members experience various types of interactions. According to social exchange theory, the theoretical foundation of LMX, organizational members who receive high social support from a leader has correspondingly improved job performance, which leads to a social exchange relationship that the leader is satisfied with. In contrast, organizational members who receive little social support from the leader show low work performance and ultimately have limited interaction with the leader [3]. More importantly, LMX emphasizes the interrelationship between leaders and members of an organization at the individual level. When the quality of the exchange relationship between leaders and members is high, trust and satisfaction, organizational attachment, and a sense of unity are effectively formed [22].

Given that, Jin and Kim [29] reported that airline employees’ LMX positively impacts organizational effectiveness, such as organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Lim [30] also reported that LMX significantly affected the organizational commitment and job satisfaction of organizational members. Therefore, a hypothesis was established as follows:

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

Sports center employees’ leader-member exchange (LMX) will have a positive effect on organizational commitment.

2.5. Mediating Role of Leader-Member Exchange Relationship (LMX)

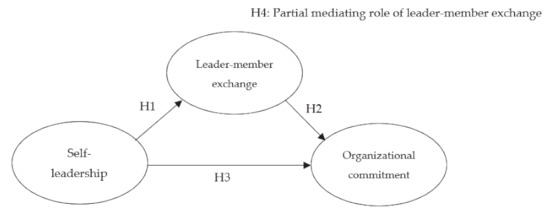

Based on LMX theory, leaders are the most influential in delivering specific roles to organizational members [31]. While all members of an organization are treated as a unit, a relationship between a leader and a specific member is an individual and unique one-to-one relationship, and leadership effectiveness varies depending on the characteristics of these relationships [3]. Organizational members with good relationships with their supervisors tend to have higher job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and work performance than those with poor relationships with supervisors [15]. In previous studies related to LMX, trust and loyalty are important factors that can improve LMX. The number of resources, information, and emotional support exchanged between a leader and a member determines the quality and level of LMX, thereby determining the attitude and behavior of the members toward their work and organizations [31,32,33]. Additionally, LMX is a crucial mediator in the relationship between self-leadership and organizational effectiveness, including organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Son [3] reported that sports center employees’ self-leadership positively impacted organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intention through LMX and concluded LMX was a crucial mediator between self-leadership and organizational effectiveness. You and Lee [22] also reported a partial mediating role of airline cabin crews’ LMX in the relationship between self-leadership and team commitment. Consequently, it seems that self-leaders with a sense of ownership for their organizations contribute to improving organizational commitment by increasing internal positive energy through a desirable relationship with their leaders. Thus, the following hypothesis was suggested, and the research model of this study was presented in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Research Model.

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

Sports center members’ leader-member exchange (LMX) will have a partial mediating role in the relationship between self-leadership and organizational commitment.

3. Method

3.1. Praticipants

In this study, 175 questionnaires were distributed and collected from May to June 2022, targeting the employees of 10 sports centers in Seoul and Kyonggi province, South Korea, using a convenient sampling method. Of 175 collected questionnaires, 172 (98.3%) data were used for the final analysis, excluding the three surveys with more than three questions unanswered. Among 172 participants, 121 (70.3%) were male, and 51 (29.7%) were female. Most participants (49.4%) were in the 20–29 years old category and graduated from university (4 years) (66.9%). For the length of employment, 44.8% of the participants showed less than one year, 28.5% worked less than two years, and 18.6% worked for less than three years. Most participants (50.0%) reported earning a monthly income of less than $2000 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of Participants.

3.2. Instruments

The authors of the current study developed a 22-item survey including five demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, age, education, monthly income, and length of employment) adapting previously validated studies.

More specifically, we adapted six items to measure perceived sports center employees’ self-leadership (α = 0.88), consisting of behavior-focused strategy, natural reward strategy, and constructive thought pattern strategy from You and Lee [22]. For LMX, three items (α = 0.77) were adapted from Son [3]. Lastly, the organizational performance represented by organizational commitment was measured with three items (α = 0.85) adapted from Son [3]. Sports center employees’ self-leadership, LMX, and organizational commitment were measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The content validity was secured through the verification work of experts (two sports management professors and two sports center operators) who excluded duplicate questions from previous studies and modified unclear wording of the question items. In addition, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and reliability tests were performed on the collected data (self-leadership, LMX, organizational commitment) to secure the validity and reliability of the questionnaire.

3.3. Data Collection Procedures and Data Analysis

This study selected 175 employees from large sports centers with 20 or more employees and sports facilities performing at least three different sports located in Seoul and Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. A survey method was utilized using a convenient sampling method to collect data in this study. The researchers visited the sports centers and obtained verbal consent to participate in the study. Participants were asked to answer survey items using self-administered methods.

For statistical analysis, we conducted descriptive analysis, reliability analysis, CFA, and structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses using SPSS version 23.0 and AMOS version 23.0 in the present study. In particular, we conducted CFA to examine the measurement model in terms of its psychometric properties by testing model fit, convergent validity, discriminant validity, and reliability. We used the maximum likelihood estimation (ML) procedure. Multiple indices were utilized to assess the model fit, including chi-square, CFI (>0.90), NFI (>0.90), TLI (>0.90), RMSEA (<0.08), and SRMR (<0.08) [34]. Additionally, we tested convergent validity by assessing the average variance extracted (AVE) values. We assessed the discriminant validity by comparing average variance extracted (AVE) to the squared correlation. To test the research hypotheses, we conducted a structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis using an Analysis of Moment Structure (AMOS) 23.0 software program. We estimated the structural model by considering the socio-demographic variables as covariates.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistical analyses showed skewness (ranging from −0.66 to −85) and kurtosis (ranging from 0.50 to 1.14) values within the acceptable ranges [34]. Tolerance (0.93) and variance inflation factor (1.06) values were examined to check multicollinearity, revealing that multicollinearity was not a concern [35]. Table 2 shows descriptive statistics and correlations.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations of Variables.

4.2. Measurement Model Test

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showed an acceptable model fit (χ² = 96.38, df = 51, p = 0.01, χ²/df = 1.89, goodness of fit index [GFI] = 0.91, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.07, and standardized root mean square residual [SRMR] = 0.05) [35]. AVE values (ranging from 0.65 to 0.74) demonstrated good convergent validity [36]. Additionally, all AVE values were higher than the squared correlation of all pairs, ensuring discriminant validity [35]. The calculation of composite reliability (CR) values (ranging from 0.84 to 0.93) indicated that all measures were internally reliable (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Factor Loadings (λ), Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE).

4.3. Structural Model Test

The results of structural equation modeling (SEM), which are shown in Table 4, revealed an adequate model fit to the data (χ² = 170.81, df = 101, p = 0.01, χ²/df = 1.69, GFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.06, and SRMR = 0.05). Self-leadership was found to have significant positive impacts on LMX (β = 0.24, p < 0.01) and organizational commitment (β = 0.19, p < 0.05). LMX had a significant impact on organizational commitment (β = 0.21, p < 0.05). Thus, Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 were supported. Additionally, there were no confounding effects in the relationships among self-leadership, LMX, and organizational commitment.

Table 4.

Path Coefficients between self-leadership, leader-member exchange (LMX), and organizational commitment.

4.4. Mediating Effects of Leader-Member Exchange

We tested the mediating effects of LMX in the relationships between self-leadership and organizational commitment by comparing two rival models (partial mediation and full mediation). As seen in Table 5, the results showed no significant difference in model fit measures except the chi-square value between the partial and the full mediation models. The chi-square value for the full mediation model compared to the partial mediation model increased by 5.67, which is statistically significant with df of 1 at the alpha level of 0.05. However, the values of RMSEA, TLI, GFI, and CFI were not different between the two models. Additionally, the path coefficients for the two rival models were statistically significant, and there was no difference in the path coefficient values. Thus, it cannot be concluded that the full mediation model fits the data better than the partial mediation model, and hypothesis 4, which suggests the partial mediation role of LMX in the relationship between self-leadership and organizational commitment, was supported.

Table 5.

Model fit measures and latent path coefficients for two models.

5. Discussion

The present study investigated the effects of self-leadership on organizational commitment among sports center employees and the mediating effect of LMX in the relationship between the relevant variables in the Korean sports center operation industry context. The findings of the current study support all the proposed hypotheses.

First, the results of this study showed that sports center employees’ self-leadership had a positive impact on LMX and are supported well by prior relevant studies [3,10]. Especially, Son [3] supported the current study’s findings by reporting that sports center employees’ self-leadership positively affected operational effectiveness, such as team commitment and job satisfaction. Kim [36] further supported these findings by revealing that self-leadership of employees working at a social enterprise positively affected LMX. In fact, highly motivated self-leaders have a strong tendency to enjoy their work and, in turn, to induce a positive atmosphere within the organization, so it is easy to form desirable relationships with colleagues and supervisors [3,8]. Moreover, a self-leader with clear objectives and a serious attitude toward a given task project is likely to create quality relationships with supervisors because they recognize the self-leader as a member who can accomplish the task in a self-directed manner [6,22]. Therefore, our findings demonstrate that it is necessary to enhance the self-leadership of the members to form a positive organizational culture in a workplace and a friendly mutual relationship between leaders and members.

This study expanded the understanding of self-leadership by verifying the mediating effect of LMX on the relationship between self-leadership and organizational commitment of sports center employees. The results provide a basis for follow-up studies on organizational effectiveness, such as employees’ enthusiasm, organizational commitment, and turnover intention in the context of sports service organizations. The findings of this study also revealed that sports center employees’ self-leadership had a significant effect on organizational commitment, supporting prior literature [1,10]. You and Lee [22] supported the current study’s findings by reporting that airline cabin crew members’ self- leadership had positive impacts on team effectiveness, such as team commitment and job satisfaction. Jin and Kim [29] also supported our findings by reporting that the self-leadership of airline cabin crew is positively related to organizational commitment and that the self-leadership enhancement of organizational members is an effective measure to improve organizational effectiveness. Due to the nature of sports center work, which provides counseling and feedback on professional physical activity while face-to-face with customers, highly motivated self-leaders with clear goals for their given work are likely to form psychological ownership of their assigned tasks, and, in turn, such an attitude develops an attachment to the job and organizational commitment [3,9]. Thus, the findings provide sports center organizations with a justification for introducing and realizing a self-leadership program that enables members to perform tasks through self-directed and constructive thinking and ultimately increase their attachment to sports center organizations.

Moreover, the current study found that sports center employees’ LMX positively influenced organizational commitment. Min and Ha [7] reported that airport security employees’ LMX positively impacted organizational commitment and supported the findings of this study. Lim [30] also supported our finding by reporting that airline crew members’ LMX positively affects organizational commitment and job satisfaction. In the sports center operation business, where human service is the core competency, it is crucial to forming trust and bonds among members of the organization to provide consistent and customer-satisfying services [3]. As a favorable exchange relationship is developed based on trust between a leader and a member, the leader and the member strengthen social exchange activities in which the leader gives encouragement or psychological support to the members, and the members provide loyalty and commitment toward the leaders and organizations [15]. Thus, it is plausible that if sports center employees are confident that they are forming an amicable relationship that receives emotional support and trust from leaders, they are more likely to show psychological attachment and commitment to their organizations.

Lastly, the current study exhibited that LMX had a significant partial mediating role in the relationship between self-leadership and organizational commitment among sport center employees and supported the relevant prior literature [3,22,36]. You and Lee [22] supported this finding by demonstrating that LMX quality, which was increased through self-leadership of airline cabin crew, functioned as a mediator to improve organizational effectiveness, such as job satisfaction and commitment. Lee and Yang [37] also exhibited similar findings. They confirmed that the quality of LMX perceived by hotel employees partially mediated the relationship between self-leadership and organizational commitment. Since sports center organizations are highly dependent on human resources, it is necessary to enhance each member’s job competency and build amicable relations with supervisors and other employees to overcome the heterogeneity of service products and improve organizational effectiveness and performance. Likewise, sports center employees with a self-directed attitude toward a given task may create a psychological attachment to their organizations and strengthen organizational commitment through an amicable relationship with their supervisors.

The findings of the current study suggest practical implications for sports center organizations. First, since the managerial decisions on recruitment are crucial for the organizational and economic sustainability of sports organizations [38], our findings encourage sports center managers to establish recruitment criteria to select applicants with desirable personal characteristics and enhance the self-leadership of sports center members. If there are several candidates with similar career conditions in the recruitment process, it is required to select self-directed candidates with a strong desire for achievement. Sports center employees are generally selected through multiple interviews and health checkups. Sports center organizations must add job aptitude tests to the hiring process and select candidates who can demonstrate self-leadership, such as a self-leading personality and achievement desire to enhance organizational effectiveness and performance. Second, sports center managers should understand that quality LMX between organizational leaders and members forms over a long period. Sports center organizations must provide organizational support such as systematic and long-term mentor-mentee programs to effectively enhance LMX between leaders and members and strengthen employees’ organizational commitment. Additionally, sports centers comprise various members such as instructors, management staff, and front desk staff, efforts should be made to form a favorable organizational culture among members to enhance organization attachment by providing regular inter-departmental socializing programs.

Although the current study suggests meaningful findings, several limitations should be addressed. First, the current study collected data from South Korean sports center employees, limiting the findings’ generalizability. Thus, it may be desirable that future research consider different country settings to increase the external validity of the study’s findings. Second, although this study conducted a quantitative study using a survey method, there was a limit to understanding the relationships between self-leadership, LMX, and organizational commitment of sports center members. Therefore, it would be necessary to replicate the current study by considering qualitative study through observation and in-depth interviews.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization W.-h.S.; methodology, W.-h.S., W.-y.B. and K.K.B.; formal analysis, data curation, W.-h.S.; writing—original draft preparation, W.-h.S.; writing—review and editing, W.-h.S., W.-y.B. and K.K.B.; supervision, K.K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The present research was supported by the research fund of Dankook University in 2021. The research funding number is R202101264.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to participants’ privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chu, Y.; Lee, J. The effects of self-leadership on job satisfaction and job performance in service employees working at coffee shops. Int. J. Tour. Manag. Sci. 2017, 32, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Ji, Y.H.; Baek, W.Y.; Byon, K.K. Structural Relationship among physical self-efficacy, psychological well-being, and organizational citizenship behavior among hotel employees: Moderating effects of leisure-time physical activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, W. The effect of self-leadership on leader-member exchange (LMX) and organizational effectiveness of sport center instructors. Korea J. Sports Sci. 2017, 26, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceptureanu, E.G.; Ceptureanu, S.I.; Luchian, C.E.; Luchian, I. Quality management in project management consulting. A case study in an international consulting company. Amfiteatru Econ. 2017, 19, 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, N.; Jung, S. The effect of self-leadership on organizational performance: The mediator effect of smart work environment. J. Ind. Econ. Bus. 2020, 33, 1383–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, C.C.; Sims, H. Super leadership: Beyond the myth of heroic leadership. Organ. Dyn. 1991, 19, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.; Ha, S. A study on the self-leadership of service employees: The implication for aviation service industry. J. Aviat. Manag. Soc. Korea 2013, 11, 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Manz, C.C. Self-leadership: Toward an expanded theory of self-influence processes in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, P.C.; Houghton, D.J. Two decades of self-leadership theory and research: Past developments, present trends, and future possibilities. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 270–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Jeon, M. The relationship among emotional labor and self-leadership of employee and organizational performance by job characteristics of airport security agents. Korean J. Converg. Sci. 2022, 11, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S. The effect of employees’ self-leadership on the job engagement: Focusing on the moderating effect of overall justice. J. Digit. Converg. 2022, 20, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, R.P.; Meyer, J.P. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Pers. Psychol. 1993, 46, 259–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H. The Causal relations among the Self-Leadership, Service Orientation and Organizational Commitment of Fitness Center. Korean J. Sports Sci. 2021, 30, 541–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreitner, R.; Kinicki, A. Organizational Behavior; Mcgraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, P.R.; Gobdel, C.B. The vertical dyad linkage model of leadership: Problems and prospects. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1984, 34, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lee, D. The relationship among service quality, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty of dance sports facility. Korean Soc. Sports Sci. 2013, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. Relationship of Sports Center Employees’ Transformational Leadership with the Perceived Organizational Support, the Organizational-base Self-esteem, and the Innovative Behavior. J. Sport Leis. Stud. 2012, 50, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, J.; Kim, C. The effect of relationship marketing implementing factors on customer satisfaction, relationship quality and customer loyalty of fitness Centers. J. Sport Leis. Stud. 2010, 40, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H. The influence of self-leadership on innovative behavior or sports center instructors: Focused on the moderating effect of resistance to organizational change. Korean J. Sport Stud. 2018, 57, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strittmatter, A.M.; Hanstad, D.V.; Skirstad, B. Facilitating Sustainable Outcomes for the Organization of Youth Sports through Youth Engagement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Lee, J. The effect of flight attendants’ self-leadership on team effectiveness: Focused on the mediating effect of leader-member exchange. Aviat. Manag. Soc. Korea 2015, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G.A. Leadership in Organizations, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Graen, G.B.; Scandura, T.A. Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. Res. Organ. Behav. 1987, 9, 175–208. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, B.T.; Harris, S.G.; Armenakis, A.A.; Shook, C.L. Organizational culture and effectiveness: A study of values, attitudes, and organizational outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Tims, M.; Derks, D. Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyne, V.L.; Pierce, L.J. Psychological ownership, and feelings of possession: Three field studies predicting employee attitudes and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Kim, K. The effects of self-leadership on organizational trust, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction: Focused on airline cabin crew. J. Hosp. Tour. Stud. 2020, 22, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E. A study on the relationships among leader-member exchange (LMX), empowerment, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction: Focused on “A” airline. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 34, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienesch, R.M.; Liden, R.C. Leader–member exchange model of leadership: A critique and further development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 618–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogliser, C.C.; Schriesheim, C.A. Exploring work unit context and leader–member exchange: A multi-level perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, S.J.; Shore, L.M.; Liden, R.C. Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. The effect of self-leadership of rural community employees on organizational performance: Mediation effect of empowerment and leader-member exchange relations. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 12, 1097–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Yang, G. A Study on the Intermediating effect of LMX (Leader-Member Exchange) in the influencing relation between hotel employees’ self-leadership and organization effectiveness. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2012, 26, 525–539. [Google Scholar]

- Galdino, M.; Lesch, L.; Wicker, P. (Un)Sustainable Human Resource Management in Brazilian Football? Empirical Evidence on Coaching Recruitment and Dismissal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).