1. Introduction

Ideas travel. From Palo Alto to Port Harcourt, Madrid to Maputo or Berlin to Bluefield, Nicaragua, we meet similar vocabulary, expressions and concepts around innovation and collaboration. In this paper, we examined how organisations have facilitated the decade-long journey of the twin ideas of open innovation (OI) [

1] and university–industry collaboration (UIC) [

2], moving from the highly industrialised Nordic context to an emerging economy in Central America. We aimed to enable collaboration and new ways of working and creating value, while supporting sustainable economic and social development. While we recognise the potential importance of OI and UIC in enabling and sustaining the development of organisations, societies and individuals [

3], it is not fully clear how the combination is best diffused and locally adapted across application contexts [

4]. We noted how local contexts, history and path dependencies, and market and knowledge asymmetries, together with differences in language, culture, trust and educational backgrounds, influenced this diffusion and subsequent local adaptations [

5]. Furthermore, complexity is added to the picture through the organisations that help ideas to travel and become parts of local adaptations. These innovation intermediaries traditionally support knowledge diffusion, technology transfer, brokering, innovation management, intermediation services and systems and networks [

6,

7]. They also support the aims of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG#17), as multi-stakeholder partnerships are an important vehicle for sharing both global and local knowledge, expertise, technologies, and resources to systemically support human development [

8]. Through the combined OI–UIC focus, the innovation intermediaries help to foster innovation (SDG#9), decent work and economic growth (SDG#8), as well as access to quality education (SDG#4). They support combining global, local, internal and external knowledge [

9], and open, flexible and collaborative modes of working that support partnership-forming practices [

10,

11]. Engaging universities enables systemic approaches to societal challenges through shared value within these partnerships [

2,

12,

13,

14].

In many cases, open innovation studies identify the connection between the actors in the ecosystem through inflows and outflows of knowledge [

15], and studies such as those of Scaringella and Radziwon [

16] and Spithoven and Knockaert [

17] identify the role of universities as knowledge brokers. However, the evolutionary pathways and shifting roles that depend on the context appear to not be fully addressed, and proposed frameworks tend towards the static. This may be understandable from the perspective of, for example, limiting research complexity, but since ecosystems and the constellation of actors operating within them are dynamic and constantly evolving, we feel that it is pertinent to longitudinally examine the changing and shifting roles and practices of actors. In the OI and UIC context, innovation intermediaries appear to undertake multiple functions that are not fully clear. Recognising the importance of the intermediary organisations leads us to ask: in the context of OI and UIC, what are the roles that innovation intermediaries have in diffusing global knowledge and practices and in enabling local adaptations?

To address this question, this paper examined three interlinked and longitudinal (2012–2022) cases from the contexts of high-tech Finland, industrialised Mexico and the emerging economy of Nicaragua. Our analysis crossed one ocean, two continents and three phases of economic development. In our first adaptation, we examined how local high-tech product-oriented innovation was enabled in the Tampere region, Finland, by drawing from ideas around the benefits of open exchanges of knowledge, talent, resources [

1] and the collaboration between local universities [

12] and firms [

18]. The initiative cross-pollinated North American ideas and practices around OI-induced resource interchanges and knowledge flows between organisations [

1], together with challenge-based learning [

19,

20] within a Nordic context [

21]. The collaboration between technology-oriented student teams and industry actors informed the novel and often tacit practices of rapid prototyping and the testing of new product and service concepts [

22]. The second adaption took place in Guadalajara, Mexico, a central hub of business and digital innovation in the country. The local adaptation of the Tampere experience involved a deep engagement with academia and the codification of tacit collaboration practices to inform front-end business, service, and product development activities [

23]. The third adaptation involved moving from the Mexican industrialised country context to Nicaragua, an economically less-developed Central American country [

24].

Within these adaptations, we recognised that innovation intermediaries have had multiple roles as knowledge couriers, conveners, orchestrators, brokers and enablers of engagement [

7]. The intermediaries have enhanced cultures of collaboration [

22] and supported the co-creation of value [

25] to ensure the sustainability of the initiatives. We also noted the complexity of transferring and adapting ideas that are novel into new application contexts with distinct socio-cultural and economic development and contexts [

5].

In this paper, we start by reviewing the literature on innovation intermediaries, open innovation and value co-creation. We then elaborate on our methodological approach and present the three cases and related findings. Through our discussion, we propose a framework to describe the multiple roles of intermediaries and the process model of adaptation, discussing the implications for both academia and practitioners. The study contributes to sustainable development and multiple SDGs through modelling the diffusion and adaptation roles and processes when moving across application contexts from industrialised countries to emerging economies.

For practitioners, the design of strategies for the incorporation of universities in ecosystems requires clear roadmaps to define objectives and work plans. The proposed evolutionary model gives clear references for the development of long-term strategies in developing UIC relationships. The expectations of the stakeholders in UIC projects and their consequent support must be established in terms of the evolution and context of each intermediary. The proposed model allows for the establishment of management strategies for stakeholder expectations and the reduction of risk in projects that, due to their nature, are highly complex. The longitudinal study also allowed us to reflect on the contributions to academic knowledge and practice. We noted the scarce literature on open innovation knowledge and practice in emerging economies and aimed to make a contribution through our modelling and analysis.

2. Literature Review

Within innovation systems, innovation intermediaries [

6,

16,

26,

27] are the “engines” of innovation, playing a significant role through setting up hubs, facilitating learning, orchestrating knowledge-intensive services, and brokering activities to enable commercialisation, engagement, and value creation [

6,

28]. These intermediaries are well placed to facilitate the diffusion and local adaptation of knowledge and practices, including within collaborations between industry and academia, noting the impact that context has on the process [

2,

7]. The intermediaries often operate within networks [

29] and involve actors and contexts that do not focus solely on technology transfer [

17]. Intermediaries thrive on open innovation (OI), as coined by Chesbrough (2003) [

1] and further developed in other studies [

30,

31,

32,

33]. OI emphasises the advantages gained from the open flow of knowledge, practices and resources across places and organisations. Recently, Payán-Sánchez et al. (2021) [

34], in their overview of the field, noted the wide scholarly attention and significance of OI in the context of achieving sustainability in firms. This involves combining internal and external knowledge [

9]; supporting open, flexible collaboration [

10,

11]; promoting new technology and business models across organisational boundaries [

35]; and searching, selecting and implementing radical new ways of managing innovation [

3].

University–industry collaboration (UIC) is a prime example of the application of open innovation principles, where the knowledge exchange between two commercially unrelated entities enables the creation of novel ideas and subsequently innovation, providing value to stakeholders and societies [

2,

13]. To date, UIC has been extensively reviewed around commercialization [

18], organizational perspectives [

36] and recently, through key success factors [

13]. Driven by intense competition and a search for opportunities for growth through knowledge, engaging students has become a key source of innovation [

37]. While the literature to date has focused its attention on value creation through external ideas among Western entities [

15], less is known about the ways in which these ideas, knowledge and practices apply to emerging economies [

5]. Earlier studies have found that new, unfamiliar approaches and knowledge, together with less-developed markets, institutions and capability asymmetries, can create challenges for innovation intermediaries when moving across application contexts [

38,

39,

40].

Conducive institutions, which are understood here as the social constructions of norms, beliefs, organisations and rules in society [

41], have a significant impact on OI within UIC [

13], involving multiple actors in ecosystems [

42]. More specifically, the culture of collaboration has had a significant impact on the success of diffusing global knowledge and practices into local ecosystems [

43]. As OI aims to share knowledge, its success depends on the willingness of the individuals involved to become receptive to these new ideas and work together, hence why the culture of collaboration is a central challenge in UIC [

2,

13]. Success in the practice of applying OI in UIC is dependent on how local intermediaries manage delivery within the local service ecosystem [

44]. Seeing UIC as a service [

22] that integrates the resources of universities, entrepreneurs, social innovation actors, the public sector and students enables an understanding of collaboration as the basis of value co-creation in service ecosystems [

45,

46].

Value is understood here as the comparative appreciation of knowledge or practices defined by participant stakeholders [

45]. This economic perspective involves creating and capturing value in use, in exchange or as shared in context [

25,

47]. The co-creation of value, seen as the dynamic exchange of resources, is an essential component in service ecosystems [

46], connecting the input and output flows in OI [

32]. This exchange is moderated by the context in which value is created, as local institutions impose rules and regulations that can both enable and constrain their actions [

48,

49]. As innovation intermediaries are central to introducing new ideas (including OI and UIC) into ecosystems, they facilitate the co-creation of value in context, while participants co-create exchange and use value within practice and activities through the integration of resources between actors [

50]. This integration, governed by institutional agreements, is an essential resource for the co-creation of value [

51], enabling or limiting the interaction between actors within a service-dominant logic [

51].

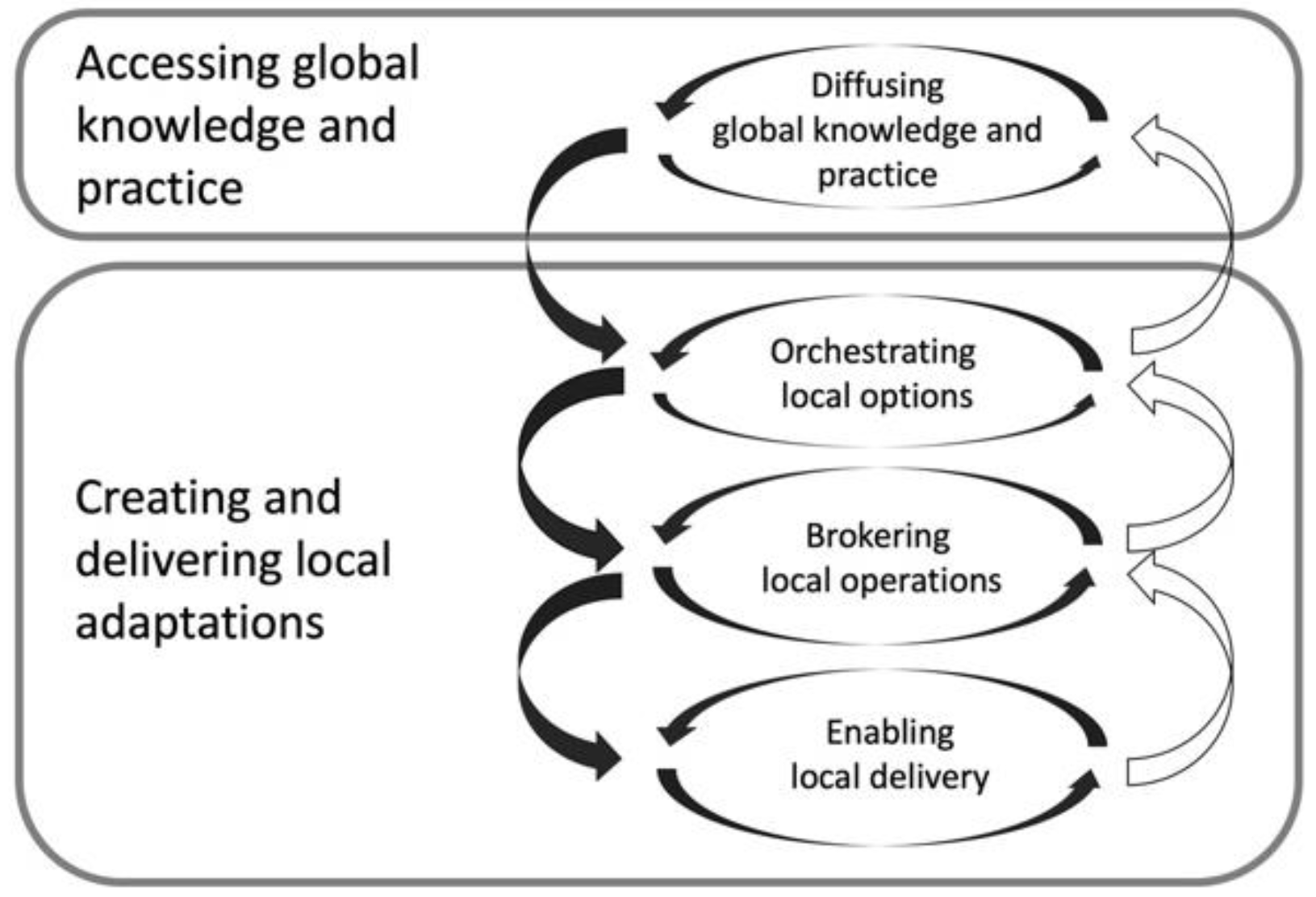

Figure 1 sums up the potential key roles that innovation intermediaries have in the context of UIC.

3. Materials and Methods

The case projects involved the diffusion of knowledge and practices, which were understood here as the application or use of an idea, belief or method. Through a multiple case study approach [

52], we theorised on the diffusion and adaptation within and across cases [

53,

54], aiming to understand the multiple roles that innovation intermediaries had, moving from highly industrialised to emerging-economy contexts. Literature informed the establishment of key study elements, the gathering of information and designs based on the research question and the theoretical axes of the transfer and adaptation models [

52,

55]. The research involved a decade-long longitudinal engagement with all three case contexts by the researchers in varying configurations, enabling direct contact and, at times, immersion within adaptation contexts.

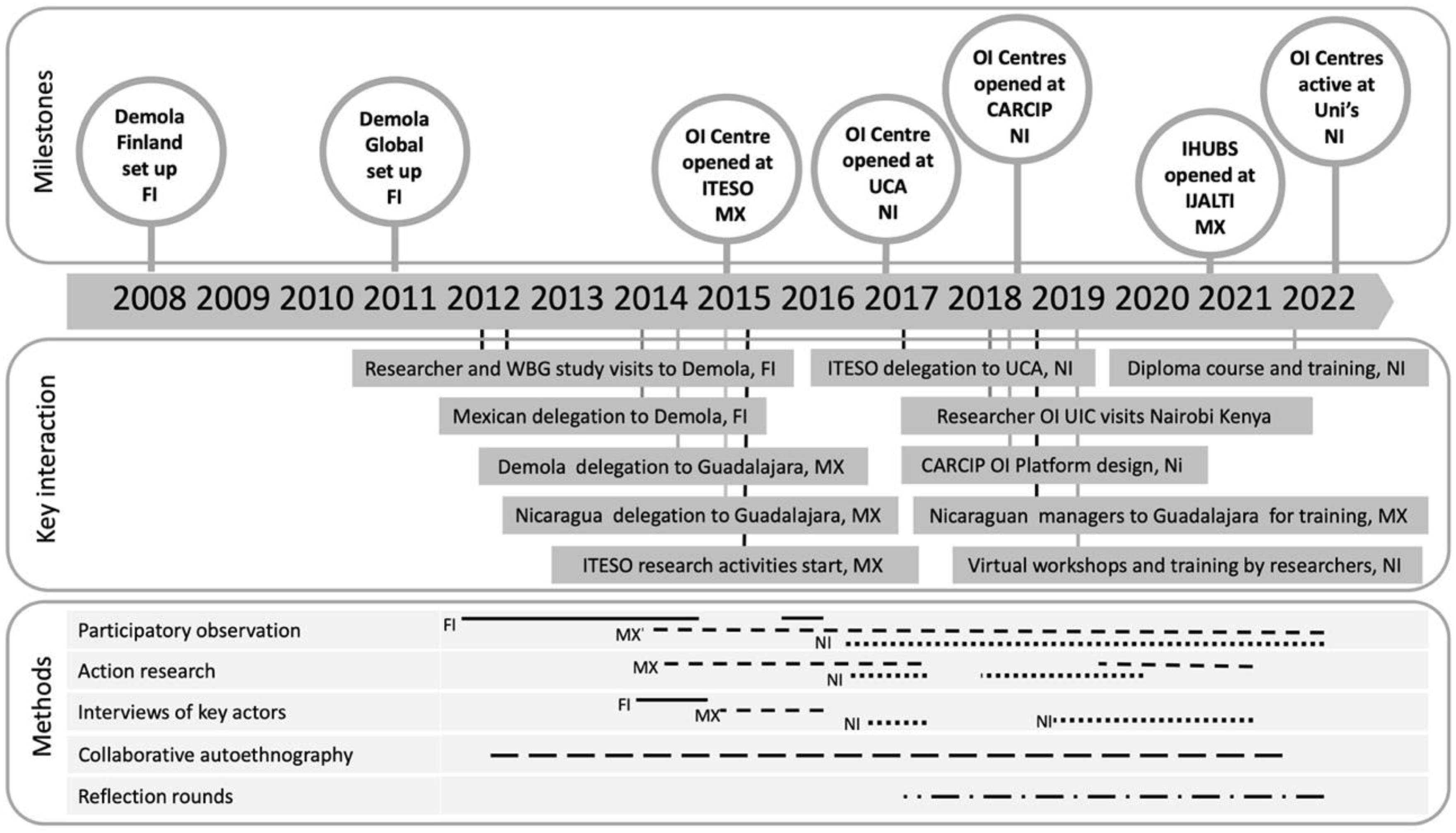

The data collection and analysis built on multiple research approaches at distinct stages, including participatory observation [

56], action research [

57], interview methods [

58] and collaborative autoethnography [

59,

60] to provide a rich pool of empirical material from several sources (see

Figure 2 and

Table 1). The authors combined their previous experience, notes and documents with secondary data, including emails, meeting minutes, proposals, reports and guidelines, to gain insights into the practices and roles of intermediaries and their temporal relations.

The initial observation and contextual engagement started in 2012 and the core data were collected between 2014 and 2022 (see

Table 1). This stage included 34 key stakeholder interviews and the observation of 35 transfer events [

58]. While formal interviews were not conducted in Mexico, the immersion and participatory roles of the researchers enabled gaining insights into this case. The authors did close to a hundred collaborative reflection rounds (weekly and bi-weekly reflective online meetings using shared whiteboards and working documents) during 2017–2022 to gain insights into the multiple types of data. As the researchers had complementary engagements with the adaptations, time-line sequencing was used to organise the data using a temporal bracketing method [

61], where the team organised the events in chronological order, resulting in a narrative of the adaptation. The clustering of the events allowed for the comparison of transitions, providing the basis for gaining insights into how context shapes idea implementation. As a result, our theoretical contribution is based on the recognition of patterns in how innovation intermediaries enable transfer and adaptation across differing application contexts. In the modelling of the process, we applied an iterative design-thinking-process model [

20,

62] with stepwise definition, using the double diamond innovation model [

63] and building on exploration, experimentation and sensemaking within the complex tasks and contexts of transfer and adaptation, where linear processes were not suitable.

4. Case Studies

In this section, we discuss the three longitudinal and interlinked case studies to provide background and context.

4.1. Finland: Tampere

Tampere gained city rights in 1779, and over time the early sawmills and small-scale ironworks grew into the second largest urban centre in Finland with an industrial base in textiles, ironworks, paper and pulp, heavy industry, automation and telecommunications. The first university moved to Tampere in 1960, and over the 1980s and 1990s, the UIC increasingly involved the local ICT (information communication technology) industry, supported by innovation policymaking, increasing openness and internationalisation of the Finnish economy. The global UIC experience (e.g., Stanford’s ME310 [

64]), together with local UIC initiatives around technology, design, and business in the 90s [

65], also supported emerging practices. Around this time, OI was coined by Chesbrough [

1]. The expansion and high profitability of the global and local ICT industry created both resources and research needs [

22], and OI helped to engage university students and graduates as users and innovators [

66], supporting the recruitment of talent.

Conducive local and national policies and the mission needs of universities and the high-tech industry led to the establishment of Demola in 2008 (e.g., see Pippola et al. (2012) [

67] and Catalá-Pérez, Rask and De-Miguel-Molina (2020) [

22]) as an innovation platform and a UIC model, focused upon new product and service development. This UIC consisted of multidisciplinary students working on real-life, time-bound challenges, provided by firms, by applying a standardised process involving mentoring. The challenges were structured around four interactive sessions involving students, invited experts, project owners and facilitators, with discovery, ideation and prototyping taking place between the sessions. This interaction was facilitated by the low-power distances that exist in the Nordic countries, the independent nature of the higher education studies in Finland and the need of technology firms to find new ways of innovating and recruiting talent [

65]. This resulted in firms providing a high degree of internal and external endorsement for the way of working at Demola and a shift in the culture of collaboration towards open innovation.

The process was highly standardised, and the intellectual property remained with the student teams with pre-determined purchase rights for the engaged firm. The students were eligible to receive degree credits from the projects. Originally operated by Hermia Oy, a semi-public technology agency with regional public funding, Demola was supported by the three regional universities of Tampere. As a key enabler, the regional Nokia Research Centre facilitated the diffusion of the Demola innovation model, engaging with young talent and acting as a peer reference organisation for other key players. By 2011, Demola had been included in the set of national policy models aimed at boosting innovation in Finland, beginning its process of internationalisation and leading to the establishment of Demola Global and a series of international nodes. In a parallel development, the ICT and Innovation and Entrepreneurship units of the World Bank Group (WBG), together with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Finland, engaged Aalto University in Finland in 2012 to deliver innovation management and capability training, with cohorts of senior emerging-economy civil servants and bank staff visiting the Tampere ecosystem and Demola, which was facilitated by one of the researchers.

Catalá-Pérez, Rask and De-Miguel-Molina (2020) [

22] noted the value creation and distribution across a quadruple helix [

68], where value in context is generated in the overall ecosystem around Demola, with teams and firms creating and capturing value in knowledge exchange. Individual students benefit from value in the use of created opportunities and knowledge from real-life work experience, instrumental and professional skills, and competencies in innovation, new methodologies and collaboration, combined with jobs, self-employment and academic recognition. The Tampere universities benefited through new teaching and learning environments, enhanced faculty capabilities, and connectedness with enterprise actors, involving research and consulting opportunities and potential revenue through intellectual property rights (IPR). Participating firms captured value through engaging in novel, networked, international innovation contexts and culture, through low-risk engagement with external new knowledge, ideas and insights, and with the potential of recruiting next-generation talent. Finally, the engagement for the public sector enabled the leading of local and regional mindset changes towards collaborative cultures, leading to an enhanced innovation performance in cities and regions.

At the time of writing, Demola was present in 18 countries and 50 universities, having engaged with over 750,000 students through OI and IUC (Demola 2022). Since 2008, Demola has maintained the foundations of their business model, which are the creation of networks and the exchange of value through the solution of problems: first local, then regional and now global. The continuity of the application of these principles has helped its role as an intermediary evolve systematically. Currently the organization is exploring new opportunities based on business intelligence and trend-information management. In addition to continuing with business projects connected with students, they have launched pilots for the attention of students around the world to address global problems.

4.2. Mexico: Guadalajara

By 2012, partly due to the past researcher-supported international study visits, the Demola experience had attracted the attention of audiences as far as Mexico, prompting an initial visit by a government–industry–academy delegation to the Tampere and Demola facilities. As a result of this visit, in July 2014, the first OI meeting in Latin America took place in Guadalajara, Mexico. With a 5 m metropolitan population, Guadalajara is Mexico’s third largest urban area and an international hub of tech, finance and art. Founded in 1542 as the capital of Nueva Galicia in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, the city grew through the 18th century’s mass migrations and industrialisation to over 1 m (1964) inhabitants (and to 2.5 m by 1980). The early first university (1791) and printing press (1793) foresaw the emergence of the key digital technology hub in Mexico.

Soon after the 2014 meeting, the Western Institute of Technology and Higher Education (ITESO) entered into an agreement with Demola Global to set up and host the first OI centre in Mexico. By now, Demola was already operating in a series of international locations [

22], and the ITESO Innovation and Technology Management Centre (CEGINT) became the newest host. A team of three consultants and five volunteer professors (including two of the researchers) worked to launch and facilitate the launching of innovation projects in January 2015. The two Demola staff-training visits around open innovation, services and co-creation in September and December 2014 uncovered the challenges of students moving from internships, social projects or professional application projects as “cheap labour” into new roles as partners and co-creators of value with companies seeking ideas and solutions in the innovation centre. Concepts such as challenge-based learning, collaboration, connection management and ecosystems were new and exciting, but were also seen as abstract and lacking in foreseeable deliverables and measurable metrics of success (subsequently, with important consequences).

Opening the OI centre required intense training, the preparation of facilities and an aggressive call to engage stakeholders managed by CEGINT at ITESO with participation of the researchers. Targeting other universities, government, and key high-tech anchor firms of the “Mexican Silicon Valley” in Guadalajara produced varied responses, ranging from enthusiastic embraces to incredulous questioning of the hitherto unknown OI-based collaboration, and the “it is not done here” rejection by business organizations. Challenges at ITESO itself were partly overcome through awarding academic credits to participating students, a key success factor in the call for talent. Altogether, ten firms responded to the call for innovation challenges linked to their needs or future strategy, having been convinced of the need to experiment with new ways to boost the ecosystem, and in January 2015 the first season started with ten challenges, fifty students and five faculty mentors. The technology transfer strategy of Demola relied on weekly accompaniment, with facilitators learning as the projects progressed, adding complexity to the process. Two further Demola staff visits ended with the presentation of projects at the end of the season.

Notwithstanding impressive initial projects and high satisfaction levels, the participants had concerns with the next steps. With the implementation of the ideas not being contemplated in the model, the results could not be compared to traditional innovation models. Unfamiliar problems arose with the premise that the students would be partners in the idea, being able to receive shares in it or purchase the rights; how would this be conducted in a local context? The model gave few clues and gave the impression of “a fun thing to do” but also of an incomplete process, uncertainty about how the local context should be accommodated and the consequences of participating in this. In May 2015, the OI model was adjusted, improving student participation and co-creation meetings.

Within ITESO, the project’s success was initially seen through the profitability of the training centre, without consideration for the intangible innovation benefits, thus limiting scalability and creating frustration among the project sponsors. Other players in the ecosystem, such as the state government and the IT industry chamber, also chose to launch their own open innovation initiatives, which were examples that other universities followed, atomising the focused opportunity. In addition, the initial aversion of companies to collaborate with students in a different modality lasted longer than expected, significantly complicating scaling up. Today, the OI Centre is still in operation, delivering projects alongside companies with a limited connection to the ecosystem, but without the involvement of Demola since 2017.

Two recent complementary streams of activities have emerged from the OI Centre. During October 2015, the ITESO research team became interested in the Demola project. By starting with the first post-graduate studies on co-creation, the group has built a stream of research around service science, open innovation, platforms and ecosystems of innovation and entrepreneurship. In another line of development, which sought better collaboration between companies in the technological sector of Guadalajara, the Information Technology Institute of Jalisco (IJALTI) launched the IHUBS initiative in March 2021 as a team-driven business platform by applying OI to the solution of challenges from governments and other companies who were expanding OI practice beyond UIC. Finally, in the case of Guadalajara, the innovation intermediary activities that began in 2014 have struggled to achieve a consistent growth in the flow of OI and UIC activities, even though the original implementation team of consultants and researchers has remained affiliated with ITESO. As in the case of IHUBs, practices have expanded through transfers to different contexts in the wider entrepreneurial and innovation ecosystem.

4.3. Nicaragua: Multiple Sites

In May 2015, a combined Nicaraguan and WBG team visited the ITESO OI centre in Guadalajara. While some stakeholders had expressed doubts about the utility of these novel approaches, the adaptation of practices generated in Europe in a Latin American environment had not gone unnoticed. The Guadalajara adaptation by ITESO led to a functional practice in Mexico, and the demonstrations and opportunities to watch the teams at work resulted in an interest in replicating the steps in Nicaragua, resulting in a Demola Finland team visiting the country a few weeks later to develop a similar project.

Nicaragua has a population of 6.6 m (2020) and a GDP per capita of USD 1905 (2020, equivalent to USD 5642 PPP). With Nicaragua being one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere, a distinctly different context was created to the previous two cases. Independent since 1821, the country has seen natural disasters, political unrest, dictatorship, war and occupation at various times. While two-thirds of the multi-ethnic population is urban, low formal employment (c.50%), high underemployment (c.50%), low growth (−2% in 2020) and a Gini coefficient of 0.49 [

69] imply significant human capability development and resource needs, especially in scientific and technical information (STI) programs within UIC. The first of the current eight universities, the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua, was founded in 1812, and the 2002 tertiary education enrolment rate was 17% [

70]. Systemic challenges exist in the quality of, distribution of and access to higher education [

71].

Despite the enthusiasm of both parties, an agreement between the Nicaraguan Government and Demola Global was not reached and the OI Centre initiative did not go forward. However, resulting from the earlier Nicaraguan visit, one of the researchers was invited in January 2017 to visit the Central American University (UCA) in Nicaragua (a Jesuit university, as ITESO). For two months, the ITESO academic staff accompanied the training, the call for actors and the preparations for the new innovation centre inaugurated in February. To enable this, the innovation cycle and related knowledge and practice was documented for the first time with the experiences and learning collected up to that moment.

In a parallel development and as a result of the study visits to Demola in Finland, OI and UIC were incorporated into several WBG programmes with an initial UIC platform designed (in 2017–2018) to contribute to the competitiveness of the Kenyan economy [

39]. Another project engaging these principles was the Caribbean Regional Communications Program (CARCIP) in Nicaragua (2016–2022) [

24]. The Nicaraguan government, with WBG support, had continued the development of the digital innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystem, and the CARCIP project was activated in August 2016 with the innovation component in May 2018. One of the deliverables was an industry–academia collaboration platform based on OI. By this time, the former lead of the UCA first-generation OI centre had joined the new initiative, in addition to a team that included two of the researchers who designed and launched the first Nicaraguan OI centres and related platforms in Bluefields, and a few weeks later, in Bilwi. Informed by the UCA project, the first operational manuals for the OI centres and facilitators were prepared. Over three months, close to fifty persons were trained as leaders and staff for the OI centres at Nicaraguan universities. Three additional OI centres (Bonanza, Las Minas, and El Rama) were opened in August 2019, expanding the network in order to share knowledge, information and practices. This was followed by Estelí and León in October 2020, and Managua and Nueva Guinea in November 2021. The network in Nicaragua extended altogether to nine locations (Bilwi, Bluefields, Bonanza, Las Minas, El Rama, Estelí, Leon, Managua and Nueva Guinea) across the Bluefields Indian and Caribbean University (BICU), the University of the Autonomous Regions of the Nicaraguan Caribbean Coast (URACC), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua (UNAN) and Facultad Regional Multidisciplinaria (FAREM).

In November 2018, while the OI centres in Nicaragua were delivering their round of projects, a delegation of eleven Nicaraguan managers visited Guadalajara for an intensive course on leadership skills in innovation, interviewing and visiting university innovation centres. By June 2019, the focus had shifted in the Nicaraguan ecosystem. With close to three hundred selected local entrepreneurs, CARCIP organised virtual workshops (these were virtual due to COVID-19) on the application of OI and general innovation and entrepreneurship tools in process management, service design and innovation sprints, raising awareness among local actors and government players, such as the Ministry of Creative Economy project. A further virtual diploma course was held for OI centre leaders and facilitators in July of the same year, and further training was delivered to integrate business acceleration with OI practices in April 2022.

At the time of writing, with the successful CARCIP project ending, stakeholders such as the National University Council, the Ministry of Creative Economy and the Nicaraguan Council of Science and Technology (CONICyT) developed a long-term national innovation strategy. Informants noted that CARCIP has demonstrated an effective way to connect universities and firms, and the platforms create ideal spaces for the development and testing of future initiatives and alliances with multiple organisations. In the case of Nicaragua, the innovation intermediary roles originally established for CARCIP have gradually been delegated to a university-led network of UIC OI centres, helping to maintain consistency and continuity in the maturing transfer of knowledge and practices.

5. Findings from the Cases

The three cases highlighted the importance of the multiple roles that innovation intermediaries have in the diffusion and local adaptation of knowledge and practice through knowledge couriering, orchestrating, brokering and enabling engagement. We also noted the diversity of actors at distinct stages. In the first adaptation, Tampere, the initial intermediary was a development corporation (Hermia Oy, Tampere, Finland), set up jointly by the key ecosystem actors (the city, the regional authorities, the area’s universities and local research centres), which convened actors and orchestrated the establishment of a dedicated UIC organisation, Demola [

72]. Brokering by Demola enabled university engagement. In the Mexico case, a single institution, ITESO, initially convened actors while delegating the orchestration and brokering and enabling the adaptation of activities to a specific entity within the university (CEGINT). In this, they were initially aided by the WBG and Demola Global experts, acting as knowledge couriers of the latest global knowledge and practice, and thus supporting local adaptation. In the Nicaraguan context, the Nicaraguan Government, together with the WBG, jointly convened actors and orchestrated the set-up of an implementing intermediary (CARCIP), which were supported by ITESO as a knowledge courier. The subsequent brokering was led by CARCIP, which led the adaptation through the formation of the innovation centres (at various universities), which played the local intermediary roles of enabling the delivery of the services and were supported by ITESO. Some intermediary actors shifted their roles over time, i.e., moving from adaptation intermediaries to knowledge couriers (e.g., ITESO); some had a focus on single roles (e.g., the WBG acting solely as a knowledge courier), while others managed multiple roles (such as CARCIP’s orchestration, brokering and engaging of actors).

The findings also indicated the importance of the culture of collaboration as an enabler of both OI and UIC, impacting on both the diffusion and adaptation of knowledge and practices. As an intermediary within the Tampere ecosystem, Demola has benefitted from the supportive alignment of regional policymakers, universities, and research institutions around fostering collaboration; providing access to opportunities and resources; reducing operational constraints; and helping to embed the collaboration culture in UIC between student groups and regional firms. Over time, intermediary activities have evolved from promoting engagement and collaboration to developing processes leading to the generation of value for students, universities and participating firms. In Guadalajara, CEGINT at ITESO initially benefitted from the knowledge, and demonstrated practices through the knowledge courier intermediary, Demola. However, an ecosystem-wide alignment with local actors was difficult to achieve due to a lack of past institutionalised UIC, open-ended interaction practices and public funding (for example, Howells, Ramlogan and Cheng (2012) [

7] note the challenges of UIC). In Guadalajara, universities traditionally had not been enterprise partners, and a combination of UIC and OI approaches needed time to create a credible track record, despite the initial success. The initial collaboration maintained a focus on the front-end concepts and solutions, and the entrepreneurial ecosystem only recently gravitated towards achieving tangible concepts of market value through OI within enterprise-to-enterprise collaboration. In Nicaragua, the mix of external parties (the WBG and ITESO) and local endorsing authorities created the initial enabling institutional mix to kickstart new forms of collaboration.

Finally, we perceived the need to show and deliver tangible benefits from the collaboration through value co-creation and capture. While the short-term results in new contexts appear singularly encouraging (as in the case of Nicaragua), long-term sustainability will no doubt be dependent on how the value continues to be co-created and captured equitably by all actors. At every adaptation, sustainability has been linked to capturing the benefits of OI and UIC, e.g., from having access to new opportunities to capturing novel resources in the delivery of services [

13]. We noted the stepwise progress on the cases, where courier organisations enabled the identification of opportunities, leading to localised meaning-making, decisions, and the delivery of UIC services. Just as much as value co-creation (and related capture) [

25,

73] is at the core of sustainable UIC, it takes different forms in the adaptations. We also noted the value of co-creating initial opportunities (e.g., through the convening role of the WBG) and the building of options in the new contexts (as ITESO did in Guadalajara). This was followed by the creation of new forms of participation across application contexts (however, as we saw, these mostly always involved universities as key partners), down to the value co-created in the actual delivery of the projects in local contexts. In line with seeing the UIC from the service-dominant logic (SDL) [

74] perspective, we see value as being co-created at every stage of the process. We have summarised the key findings in

Table 2.

6. Discussion

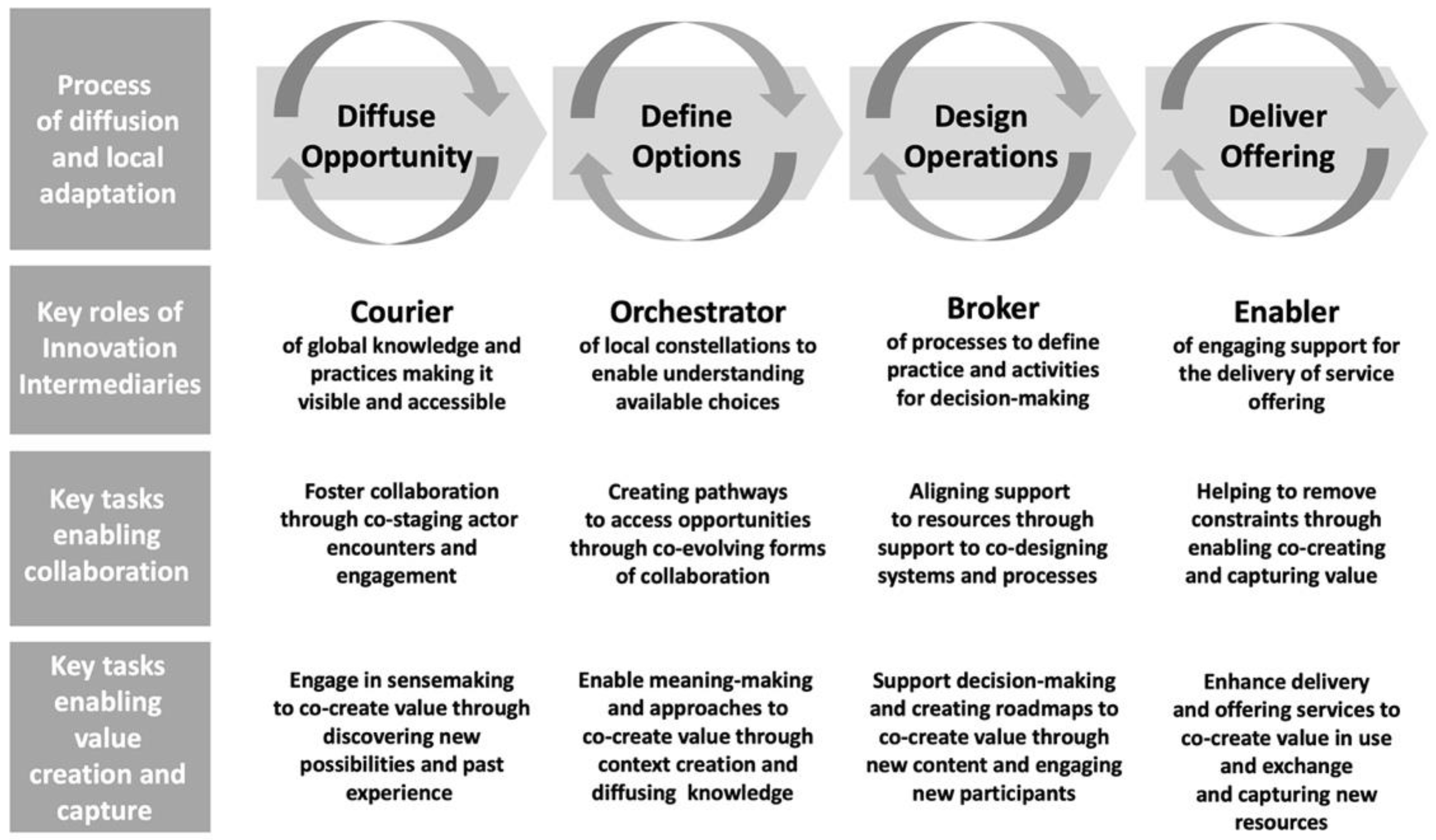

In this paper, we aimed to understand the role of innovation intermediaries in the diffusion and enabling of local adaptations through OI and UIC. By linking the various elements from the findings, we proposed a generic stepwise process underpinning the work of innovation intermediaries that would like to engage in diffusion and adaptation processes. We argue that diffusing global knowledge and practices implies initially adopting a knowledge courier role, disseminating the idea and value of collaboration, open innovation and new ways of working between industry and academia [

2,

12]. As knowledge couriers, innovation intermediaries support making global ideas and practices visible and accessible in new application contexts, as in the case of the WBG’s organisation of study visits and training. This is the initial step in fostering current and potential collaborations through convening actor encounters and engagement. Engaging in early-stage collaborative sensemaking allows for the co-creation of value with local stakeholders through discovering the range of possibilities and leveraging past learning [

11]. This in turn enables an understanding of the knowledge and practices underpinning choices to be made in setting up initiatives (as seen in the case of Demola Global supporting ITESO, and subsequently, ITESO supporting UCA). Suffice to say, this complex role requires a deep understanding of the target context, a critical mindset, experience and an understanding of the acceptability of courier organisations as credible and relevant partners to local stakeholders. The evidence from the Nicaragua case suggests that support from a Latin American partner was especially conducive to bridging the psychic distance between new ideas and the local context, due to a common language and cultural affinity [

24].

Defining local opportunity spaces builds on understanding the potential, acceptability and affordability of global knowledge and practices in the local context. The intermediary has a role as an orchestrator convening local actors to identify and create pathways to existing and potential new local opportunities [

2,

18]. This interaction underpins co-evolving forms of collaboration and creates value through the diffusion of new knowledge, the meaning-making of appropriate local solutions and the development of new application contexts for OI and UIC. Furthermore, the orchestrator of these novel constellations has a key enabling role in the co-creation of understanding with local stakeholders around available choices and in defining feasible options, allowing the creation of roadmaps and pathways forward [

66]. In the three cases, the intermediaries had significant roles as orchestrators. In Tampere, Hermia set up Demola to act as a locus of operations, while ITESO built up the constellation of initial actors and activities in the Guadalajara context. A combination of organisations (the Government of Nicaragua, supported by the WBG and ITESO) acted jointly as an intermediary, creating the group of actors and activities around the CARCIP project [

16]. One of the key challenges in the orchestration of the OI and UIC agenda in an emerging-economy context is the lack of evidence-based knowledge of what works and what does not [

44]. Observing this lack led to a codification process in Guadalajara of the knowledge and practices that had previously been used in Tampere. The first international adaptation between the cases involved a significant amount of tacit knowledge, while the second one benefitted from a more codified knowledge base.

Designing sustainable operations supports stakeholders in developing and defining practices and approaches for decision-making around implementing operations (e.g., Demola supporting initial ITESO/CEGINT practices, and CARCIP’s support of the Nicaraguan OI Centres). These brokering activities involve the processes of designing operations that help to co-create and sustain a culture of collaboration that enables value creation across the interactions through enhanced decision-making, road-mapping, making the latest content available and inviting new participants to join [

39]. A key collaboration focus would rest on aligning support to gain resources for co-designing systems, processes and delivery. The key task challenges of ITESO were in this space. To note, Demola Global has invested significantly in developing processes over the years, which has enabled their global scaling up through systemic management approaches and principles.

Finally, supporting the delivery of valuable offerings is a key role for intermediaries in their activities with the local student teams, firms and other stakeholders [

2,

7]. This is a core activity in the case of Demola, ITESO’s CEGINT and the OI Centres at the various universities in Nicaragua. It is also the level where tangible results are created, products and services are conceptualised and where products and services are tested for suitability. Intermediary support can help to remove constraints while enabling the co-creating and capturing of value, while also capturing new resources. In

Figure 3, we propose a framework for the procedure of transferring and adapting OI and UIC knowledge and practices, highlighting the stepwise process and the key issues related to enabling collaboration and value co-creation.

Some further insights emerged from the set of cases that were linked to role needs, sequencing, the evolutionary nature of the process and the integration needs and value co-creation by intermediaries involved in the transfer and adaptation. We noted that all the identified roles were necessary and needed to be adopted by actors involved in the process. That said, there appeared to be flexibility in terms of intermediaries adopting single or multiple roles, and in moving from one role to another, even filling a single role through the joint efforts of various organisations. These roles have a singular sequence and a direction, moving from knowledge couriering to orchestrating, brokering and enabling engagement. In this, we extend the work on intermediaries [

6,

7,

26] through understanding the interlinked nature of roles and their stepwise application and progression.

While this sequence appears to be linear, the cases demonstrated a non-linear, evolutionary process that was both complex and application context-dependent, calling for iterative sensemaking methods when developing initiatives, such as design-thinking [

62,

75], together with processes that uncover solutions over time, as in the methods applied through the Double Diamond (see

Figure 3) [

63]. Engaging in OI and UIC creates significant demand for the flexibility and adaptability of the intermediaries that work together, as collaborative cultures do not evolve overnight, confirming the need for appropriate working methods to achieve sustainable results [

10,

11]. The practice of OI in the UIC context also requires consistency of application, continuity in resourcing and dedication from the actors involved to achieve the sustainable management of innovation [

3], and significant attention is needed to ensure strategic alignment and activity integration in the collaboration of participating intermediaries [

9,

12]. This complexity becomes apparent when aiming to scale up initiatives.

While short-term value co-creation for students is often apparent immediately through their real-time participation and use of methods, tools and approaches within projects, the value co-creation of universities through exchanges will often only accrue over time and through various application cycles, making systemic approaches to collaboration and partnerships important [

9,

12]. For firms and social innovators, value co-creation may depend on the willingness, ability and resources of the collaborating organisations to take concepts to the market and establish their commercial exchange or utility value [

18]. Overall, we noted that the varied nature and multiple levels of value co-creation were in line with the findings of Chandler and Vargo (2011) [

25] and Lusch and Nambisan (2015) [

46], when understanding intermediaries as providing services within ecosystems [

24].

Establishing effective indicators linked to OI and UIC initiatives is complex, as long-term benefits may be systemic and difficult to quantify, with outcomes that may not coincide with the initial expectations, and that may require systemic innovation management practices to achieve sustainable gains [

3]. We noted, however, that OI and UIC practices are also very flexible and can be implemented in many ways, which helps to maintain OI as an inter-organizational constant that does not depend on the models to which it is applied, but on the application context in which the actors interact, supporting different forms of management, innovation or collaboration, also outside of or complementing the UIC context. To note, universities are uniquely placed in local ecosystems as long-term, stable intermediaries; thus, they are well-suited as anchors for local adaptations. Finally, in terms of sustainable development, we noted the multiple contributions that the combined OI and UIC initiatives may make towards multi-stakeholder partnerships through sharing knowledge, expertise, technologies and resources (SDG#17), fostering innovation (SDG#9), generating decent work and economic growth (SDG#8) and contributing to quality education (SDG#4).

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we aimed to understand how innovation intermediaries enable the diffusion and local adaptation of knowledge and practices. Initiatives building on open innovation and university–industry collaboration have the potential to change cultures of collaboration as well as the talent and innovation landscapes and to create long-term sustainable and systemic competitive advantages for participants at all levels, contributing to multiple SDGs. We noted the importance of understanding the multiple roles with which intermediaries need to engage, their sequencing, the evolutionary nature of the transfer and adaptation process and the need to align the efforts of multiple intermediaries to foster collaboration and co-create tangible value. This proposed process model creates a framework for thought that can be used to inform the planning and delivery of similar initiatives. For practitioners, this indicates the structured steps needed to launch, develop and provide evolution monitoring of OI platforms in UIC.

For researchers, there is ample room for future studies. The findings and their interpretation should be further discussed from the perspective of previous studies in the broadest context possible. While the focus of this paper has been on the roles and processes related to innovation intermediaries, we note the need to investigate further the capability issues related to setting up and delivering sustainable intermediation activities. These underpin operational and business models (e.g., see Teece (2010) [

76]), and initial evidence from these cases suggests that dynamic managerial capabilities may be needed within organisations to build, integrate and reconfigure ambidextrous capabilities (see, for example, Ambrosini and Altintas (2019) [

77] for a recent review) [

78]. These enable both the exploration of new contexts (what Teece (2007) [

79] calls sensing and seizing opportunities for transformation) and subsequent exploitation, renewal and change [

80]. Similarly, the collaboration practices and value co-creation models linking service-dominant logic perspectives to the service ecosystems with OI and UIC initiatives would warrant further detailed enquiry. Finally, we note that the three cases cannot be generalised and the findings are indicative of direction only. We believe, however, that it is worthwhile to continue this work to generate further knowledge towards a more generalizable model contributing towards sustainable futures, and we hope that the proposed framework will support this process over time in novel contexts for both practitioners and academics. We furthermore note the scarce literature on open innovation knowledge and practice in emerging economies, and aim to contribute through our modelling and analysis.