Risk of Poverty Returning to the Tibetan Area of Gansu Province in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction and Literature Review

2. Research Design and Research Methods

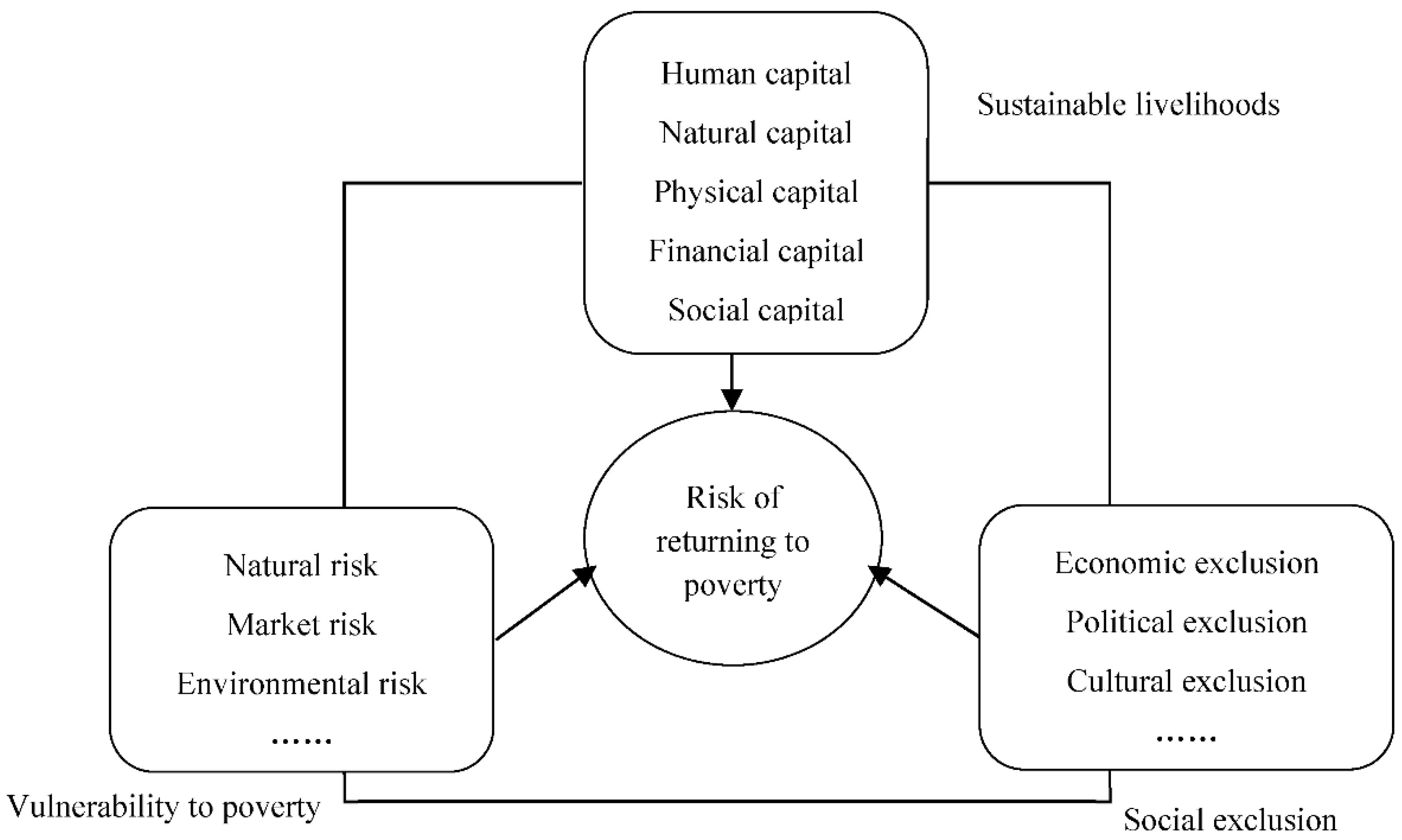

2.1. Establishment of a Risk Assessment Index System

2.1.1. Construction Basis

2.1.2. Evaluation Index System

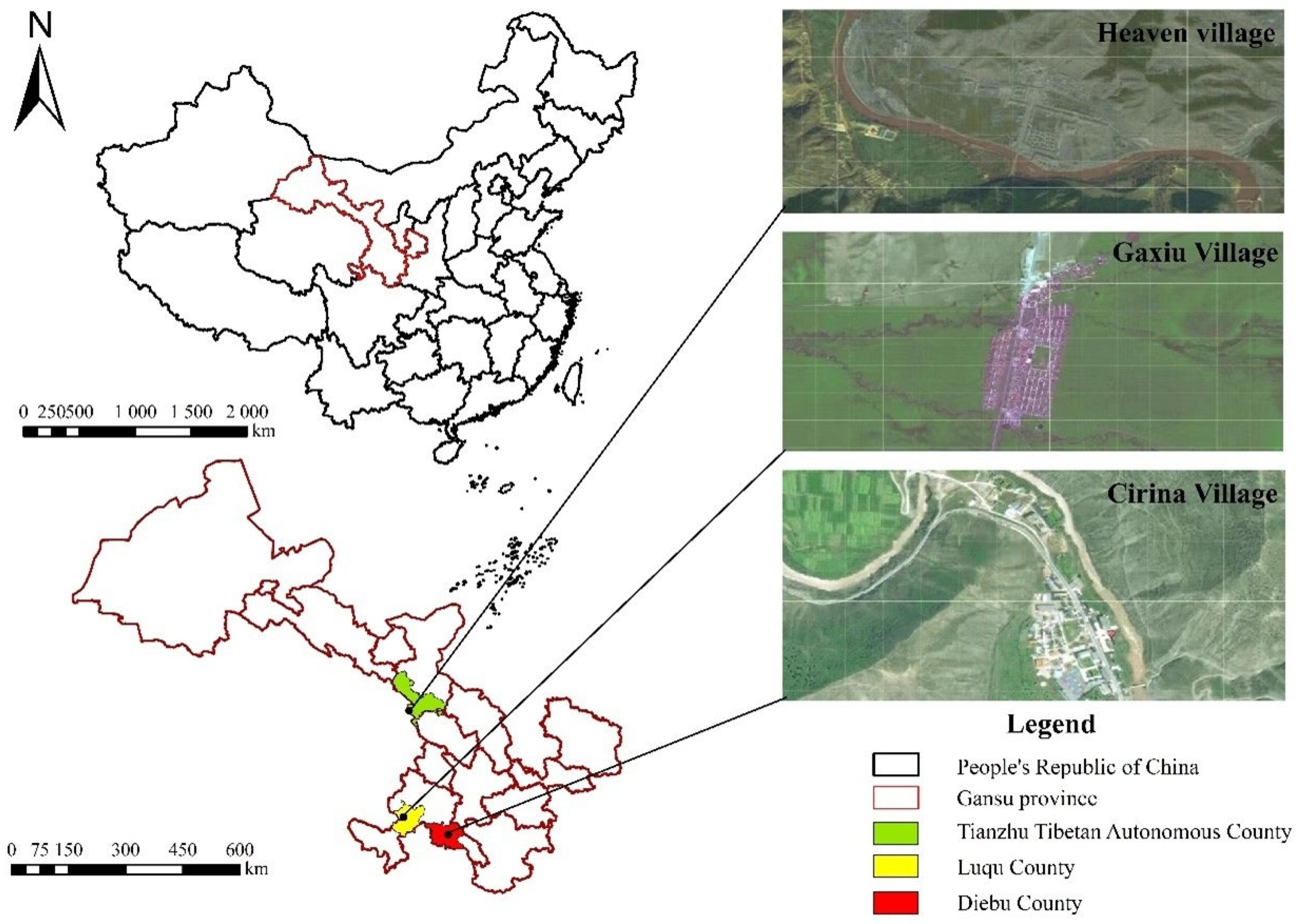

2.2. Overview and Data Source of the Study Area

2.2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2.2. Data Source

2.3. Evaluation Methods

2.3.1. Principal Component Analysis

2.3.2. K-Means Clustering Algorithm

3. Results and Analysis

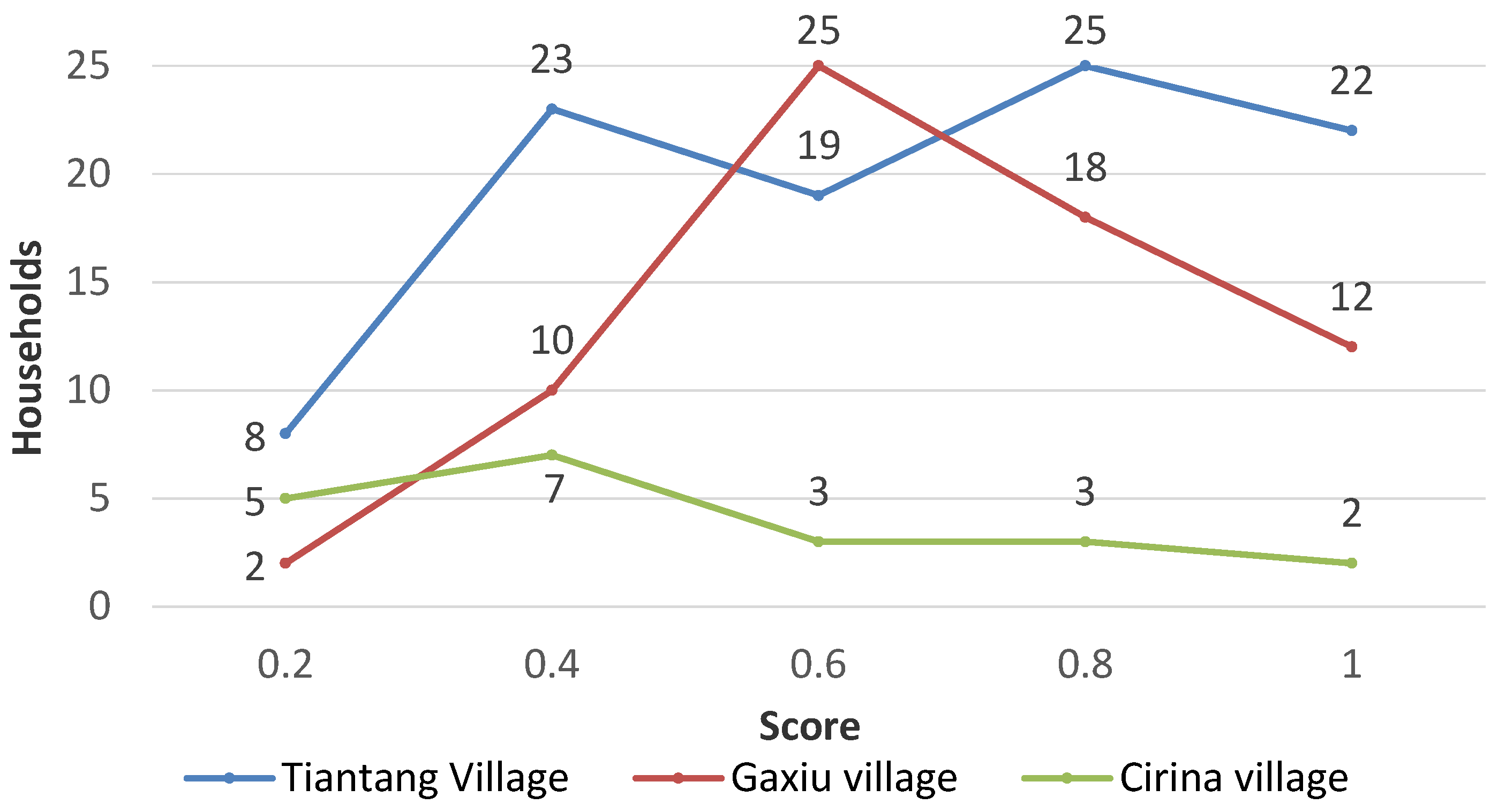

3.1. Evaluation Results

3.2. Result Analysis

3.2.1. Overall Analysis of Risk Assessment Results of Returning to Poverty

3.2.2. Comparative Analysis of Risk Assessment Results of Returning to Poverty

3.3. Early Warning Mechanism for Returning to Poverty

4. Conclusions and Discussion

5. Countermeasures and Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Office of Household Surveys, National Bureau of Statistics. The achievements of poverty alleviation and development have attracted worldwide attention, and decisive progress has been made in poverty alleviation--The fifth report of the series of reports on the achievements of economic and social development in the past 40 years of reform and opening up. China Information News, 4 September 2018; 1. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Bulletin of the People’s Republic of China on National Economic and Social Development in 2019. China Information News, 2 March 2020; 2. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva, M.M.G.T.; Kawasaki, A. Socioeconomic Vulnerability to Disaster Risk: A Case Study of Flood and Drought Impact in a Rural Sri Lankan Community. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 152, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuypers, S.; Marx, I. The Truly Vulnerable: Integrating Wealth into the Measurement of Poverty and Social Policy Effectiveness. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 142, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Luan, J.; Xie, B. An analysis on the phenomenon of returning to poverty. Explor. Econ. Probl. 2008, 3, 176–178. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Mao, K. Research on educational Prevention mechanism of Poverty return in ethnic minority areas. Res. Educ. Ethn. Minor. 2018, 29, 46–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Chen, B. Building sustainable poverty alleviation model to treat the persistent disease of rural poverty return. Soc. Sci. 2010, 1, 52–57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. “Policy to reduce poverty” calls for legislation of ecological compensation. Environ. Prot. 2011, 21, 58. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Erwin, S.; Hannes, M.; Anja, W. Explaining the impact of poverty on old-age frailty in Europe: Material, psychosocial and behavioural factors. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Atake, E.H. Health shocks in Sub-Saharan Africa: Are the poor and uninsured households more vulnerable? Health Econ. Rev. 2018, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-C.; Chen, D.-X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.-S.; Shao, K.; Dong, C.-S. Prevention of Returning to poverty: Strategic change and action mode of targeted poverty alleviation through sports. J. Shenyang Inst. Phys. Educ. 2020, 39, 29–34 + 42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Q. Community empowerment: An effective way to reduce the risk of returning to poverty among rural tourism destinations. China Tourism News, 5 June 2020; 3. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Human Development Report 2003: Millennium Development Goals: A Compact Among Nations to End Human Poverty; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. The problem that must be solved in the construction of new countryside: Peasants returning to poverty in underdeveloped areas. Spec. Area Econ. 2007, 8, 149–150. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fan, H. Research on the construction of early-warning mechanism for returning to poverty. Res. Social. Chin. Charact. 2018, 1, 57–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, K.; Chen, C.; Jiao, Y. Construction of prevention mechanism for returning to poverty in deeply impoverished areas from the perspective of holistic governance: A case study of L County in Liupanshan, Northwest China. Xinjiang Soc. Sci. 2019, 1, 137–145. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Coady, D.; Grosh, M.; Hoddinott, J. Targeting of Transfers in Developing Countries; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, Y.; Lu, C. Rural poverty reduction and poverty reduction prevention from the perspective of public investment in human capital. Fisc. Res. 2018, 5, 15–24. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.; Wang, M. The internal logic of returning to poverty: The theory and verification of poverty alleviation by vulnerability. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 45, 126–139. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ligon, E.; Schechter, L. Measuring Vulnerability. Econ. J. 2003, 113, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhuang, T.; Zhang, H.; Fu, X. Analysis on the impact of village-level development environment on poor people’s return to poverty in minority areas—Based on a survey of 67 villages in Minority areas of Sichuan, Guizhou and Chongqing. J. Agric. Technol. Econ. 2011, 2, 41–49. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, C. Study on factors of poor population returning to poverty in deep poverty area. J. Northwest Ethn. Stud. 2019, 102, 111–117. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Luo, F. Comprehensive fuzzy evaluation on the risk of returning to poverty of residents in rural tourism destinations: Based on the perspective of sustainable livelihood capital. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2018, 12, 100–104, 112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. Study on the Risk and Blocking Mechanism of Farmers Returning to Poverty in Ethnic Tourism Villages under Sustainable Livelihood. Master’s Thesis, Guilin University of Technology, Guilin, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X. Research on Risk Identification and Prevention and Control of Returning to Poverty: Based on an Empirical Investigation of L Township in Guizhou Province. Master’s Thesis, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Fan, X.; Wu, Y.; Jin, H.; Qi, X. Risk and mechanism of returning to poverty in poor mountainous counties: Based on multidimensional perspective of returning to poverty. J. Fujian Agric. For. Univ. 2020, 23, 11–17, 36. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. Study on Mechanism of Anti-Poverty Return in Jinggangshan under Region-Wide Tourism. Master’s Thesis, Nanchang University, Nanchang, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, Y. Measurement and decomposition of multidimensional return to poverty of farmers in deep poverty area. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 60–65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. Construction of Risk Evaluation Index System for Returning to Poverty in K Town of Agricultural Area of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.; Xue, X. Risk Assessment of Returning to poverty: Based on a survey of typical poor counties in western Henan province. J. Henan Polytech. Univ. 2021, 22, 22–30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Shu, D.; Jin, C.; He, X. Risk of returning to poverty in post-Poverty Era and insurance anti-poverty countermeasures: Based on the investigation of A District in Nanjing city. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2020, 48, 7–13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tian, K. Prediction Model of Poverty Return Based on Logistic Regression Analysis. Master’s Thesis, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, China, 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Wu, Y.; Gong, Y. Risk prediction and reason analysis of poverty return of registered poor Households: Based on field monitoring data of registered poor households in 25 provinces (autonomous regions and municipalities) in 2019. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. 2012, 22, 110–120. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H. Research and Application of Prediction Model for Poverty Reduction Based on Data Mining. Master’s Thesis, Shaanxi Normal University, Shaanxi, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, N.; Zheng, W. Measurement of Multidimensional Return to poverty of Migrant workers in China. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2017, 6, 58–69. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Cai, C.; Teng, J. Research on risk assessment and long-term prevention mechanism of returning to poverty in the context of rural revitalization. J. Luoyang Inst. Sci. Technol. 2019, 34, 38–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Li, H.; Hou, L.; Zhao, Z. Risk identification and early-warning mechanism construction of returning to poverty in rural tourism destinations from the perspective of sustainable livelihood: A case study of W Village, Enshi Prefecture, Hubei Province. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2022, 36, 186–193. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Luo, H. Early warning and evaluation of risk of returning to poverty under the background of poverty withdrawal. Stat. Decis. 2021, 37, 81–84. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Target | Level Indicators | The Secondary Indicators | Indicator Description and Assignment | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of poverty returning | Human capital (H) | Labor force H1 | The number of household workers; 0 = 1, 1 = 2, 2 = 3, 3 = 4, 4 or more = 5. | Positive |

| Education H2 | The average educational level of the household working population. Not in school = 1, primary school = 2, junior high school = 3, senior high school/technical secondary school = 4, junior college or above = 5. | Positive | ||

| Skill training H3 | The number of times a family member participates in skills training per year; 0 = 1, 1 = 2, 2 = 3, 3 = 4, 4 or more = 5. | Positive | ||

| Ideology H4 | Family members’ willingness to continue to get rid of poverty. Very weak = 1, relatively weak = 2, average = 3, relatively strong = 4, very strong = 5. | Positive | ||

| Natural capital(N) | Cultivated area N1 | The family owns the area of farmland. Less than 1 mu = 1, 1–2 mu = 2, 2–3 mu = 3, 3–4 mu = 4, 4 mu = 5. | Positive | |

| Distance of the scenic spot N2 | The distance between the family house and the core scenic area. Within 1 km = 1, 1–3 km= 2, 3 km= 3. | Negative | ||

| Road distance N3 | Distance between family house and village road. Near = 1, general = 2, far = 3. | Negative | ||

| Physical capital (P) | Housing structure P1 | Family housing structure. Hut = 1, civil = 2, brick = 3, tile = 4, concrete = 5. | Positive | |

| Livestock number P2 | The number of cattle, horses, sheep and other livestock raised by a family (unit: head, horse, sheep); 0 = 1, 1 = 2, 2 = 3, 3 = 4, 4 and above = 5. | Positive | ||

| Fixed assets P3 | Number of consumer durables owned by households (mobile phones, televisions, computers, electric fans, refrigerators, air conditioners, washing machines, rice cookers, induction cookers, microwave ovens, solar/water heaters, motorcycles, cars, and others); 5 or less = 1, 6–7 = 2, 8–9 = 3, 10–11= 4, 12 or more = 5. | Positive | ||

| Infrastructure P4 | Number of items of infrastructure available to households (safe drinking water, safe electricity, health care, compulsory education, tourist latrines, garbage removal, rural roads, sewage treatment et al.). 1 or less = 1, 2–3 = 2, 4–5=3, 6–7 = 4,8 or more = 5. | Positive | ||

| Financial capital (F) | Income level F1 | The average annual income of each family member. CNY 3000 and below = 1, CNY 3001–6000 = 2, CNY 6001–15,000 = 3, CNY 15,001–30,000 = 4, CNY 30,001 and above = 5. | Positive | |

| Tourism management F2 | Whether the family has run the Zangjiale. If yes = 1, if no = 0. | Positive | ||

| Revenue source F3 | Number of main sources of family income (farming, labor, government subsidies, tourism, and others); 0 = 1, 1 = 2, 2 = 3, 3 = 4, 4 or more = 5. | Positive | ||

| Credit channel F4 | The number of sources (banks, credit unions, relatives and friends, local governments, and others) through which households can obtain loans; 0 = 1,1 = 2,2 = 3,3 = 4,4 or more = 5. | Positive | ||

| Social capital (S) | Social network S1 | The number of family members, relatives and friends serving as village officials or other officials; 0 = 1, 1 = 2, 2 = 3, 3 = 4, 4 or more = 5. | Positive | |

| Social mutual aid S2 | How many trusted people in the village are willing to help your family; 0 = 1, 1–2 = 2, 3–4 = 3, 5–6 = 4, 7 or more = 5. | Positive | ||

| Risk shock® | Policy weakening R1 | Whether the government’s preferential policies for your family are weakened (poverty relief, policy subsidies, land acquisition subsidies, and special support) compared with the poverty alleviation period? If yes = 1, if no = 0. | Negative | |

| Natural disaster R2 | The damage caused by natural disasters to your home. Very small = 1, relatively small = 2, average = 3, relatively large = 4, very large = 5. | Negative | ||

| Emergency R3 | The damage to your family caused by an emergency. Very small = 1, relatively small = 2, average = 3, relatively large = 4, very large = 5. | Negative | ||

| Health condition R4 | Whether a family member has a major illness or disability. If yes = 1, if no = 0. | Negative | ||

| External rejection (E) | Probability of unemployment E1 | The possibility of a family member losing his or her job. Very small = 1, relatively small = 2, average = 3, relatively large = 4, very large = 5. | Negative | |

| Right of participation E2 | Whether family members normally participate in meetings and activities organized by the village. Very little = 1, relatively little = 2, average = 3, relatively much = 4, very much = 5. | Positive |

| Principal Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Extract The Sum of Squares and Load | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | Variance Contribution Rate/% | Cumulative/% | Eigenvalue | Variance Contribution Rate/% | Cumulative/% | |

| 1 | 9.811 | 42.657 | 42.657 | 9.811 | 42.657 | 42.657 |

| 2 | 2.299 | 9.997 | 52.653 | 2.299 | 9.997 | 52.653 |

| 3 | 1.619 | 7.040 | 59.693 | 1.619 | 7.040 | 59.693 |

| 4 | 1.154 | 5.016 | 64.709 | 1.154 | 5.016 | 64.709 |

| 5 | 1.071 | 4.655 | 69.364 | 1.071 | 4.655 | 69.364 |

| 6 | 1.002 | 4.356 | 73.720 | 1.002 | 4.356 | 73.720 |

| 7 | 0.852 | 3.703 | 77.424 | |||

| 8 | 0.700 | 3.045 | 80.469 | |||

| 9 | 0.576 | 2.504 | 82.974 | |||

| 10 | 0.559 | 2.432 | 85.405 | |||

| 11 | 0.467 | 2.031 | 87.436 | |||

| 12 | 0.444 | 1.929 | 89.365 | |||

| 13 | 0.389 | 1.693 | 91.058 | |||

| 14 | 0.365 | 1.586 | 92.643 | |||

| 15 | 0.331 | 1.437 | 94.081 | |||

| 16 | 0.284 | 1.235 | 95.316 | |||

| 17 | 0.249 | 1.082 | 96.398 | |||

| 18 | 0.219 | 0.951 | 97.349 | |||

| 19 | 0.185 | 0.805 | 98.154 | |||

| 20 | 0.145 | 0.632 | 98.786 | |||

| 21 | 0.122 | 0.529 | 99.315 | |||

| 22 | 0.105 | 0.455 | 99.770 | |||

| 23 | 0.053 | 0.230 | 100.000 | |||

| Index | Component Matrix | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principal Component 1 | Principal Component 2 | Principal Component 3 | Principal Component 4 | Principal Component 5 | Principal Component 6 | |

| Labor force | 0.624 | 0.482 | −0.318 | −0.126 | −0.161 | 0.097 |

| Education | 0.525 | 0.148 | −0.312 | −0.037 | −0.128 | 0.496 |

| Skills training | 0.860 | 0.167 | −0.094 | −0.089 | 0.003 | −0.037 |

| Ideology | 0.739 | 0.024 | 0.122 | 0.116 | −0.020 | −0.231 |

| Cultivated area | 0.245 | 0.909 | −0.071 | 0.026 | 0.004 | −0.089 |

| Distance of the scenic spot | 0.833 | −0.08 | −0.053 | −0.209 | 0.029 | −0.063 |

| Road distance | 0.705 | −0.005 | −0.097 | −0.281 | 0.042 | −0.182 |

| Housing structure | 0.816 | −0.023 | 0.109 | 0.059 | 0.042 | −0.018 |

| Livestock number | 0.269 | 0.161 | 0.560 | 0.536 | 0.333 | 0.053 |

| Fixed assets | 0.898 | −0.079 | 0.039 | −0.018 | 0.05 | −0.051 |

| Infrastructure | 0.229 | −0.094 | 0.566 | −0.436 | 0.062 | 0.290 |

| Income level | 0.914 | −0.126 | 0.128 | 0.046 | 0.131 | −0.158 |

| Tourism management | 0.559 | −0.415 | −0.400 | −0.196 | −0.037 | −0.132 |

| Revenue source | 0.823 | −0.094 | 0.218 | 0.047 | 0.066 | −0.002 |

| Credit channel | 0.794 | 0.059 | 0.126 | −0.018 | 0.022 | 0.121 |

| Social network | 0.608 | 0.049 | 0.080 | 0.086 | −0.040 | 0.371 |

| Social mutual aid | −0.181 | −0.094 | −0.517 | 0.131 | 0.588 | 0.406 |

| Policy weakening | −0.746 | 0.251 | 0.087 | −0.237 | −0.021 | 0.149 |

| Natural disaster | −0.212 | −0.867 | 0.069 | 0.005 | −0.051 | 0.163 |

| Emergencies | −0.848 | 0.290 | 0.209 | 0.017 | −0.110 | 0.123 |

| Health condition | 0.361 | −0.144 | −0.318 | 0.619 | −0.346 | 0.017 |

| The probability of unemployment | 0.427 | −0.078 | 0.244 | 0.054 | −0.593 | 0.296 |

| Participatory right | 0.722 | 0.059 | 0.045 | −0.020 | 0.223 | 0.213 |

| Index | Principal Component 1 | Principal Component 2 | Principal Component 3 | Principal Component 4 | Principal Component 5 | Principal Component 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labor force | 0.199 | 0.318 | −0.250 | −0.117 | −0.156 | 0.097 |

| Education | 0.168 | 0.098 | −0.245 | −0.034 | −0.124 | 0.496 |

| Skills training | 0.275 | 0.110 | −0.074 | −0.083 | 0.003 | −0.037 |

| Ideology | 0.236 | 0.016 | 0.096 | 0.108 | −0.019 | −0.231 |

| Cultivated area | 0.078 | 0.600 | −0.056 | 0.024 | 0.004 | −0.089 |

| Distance of the scenic spot | 0.266 | −0.053 | −0.042 | −0.195 | 0.028 | −0.063 |

| Road distance | 0.225 | −0.003 | −0.076 | −0.262 | 0.041 | −0.182 |

| Housing structure | 0.261 | −0.015 | 0.086 | 0.055 | 0.041 | −0.018 |

| Livestock number | 0.086 | 0.106 | 0.440 | 0.499 | 0.322 | 0.053 |

| Fixed assets | 0.287 | −0.052 | 0.031 | −0.017 | 0.048 | −0.051 |

| Infrastructure | 0.073 | −0.062 | 0.445 | −0.406 | 0.060 | 0.290 |

| Income level | 0.292 | −0.083 | 0.101 | 0.043 | 0.127 | −0.158 |

| Tourism management | 0.178 | −0.274 | −0.314 | −0.182 | −0.036 | −0.132 |

| Revenue source | 0.263 | −0.062 | 0.171 | 0.044 | 0.064 | −0.002 |

| Credit channel | 0.253 | 0.039 | 0.099 | −0.017 | 0.021 | 0.121 |

| Social network | 0.194 | 0.032 | 0.063 | 0.080 | −0.039 | 0.371 |

| Social mutual aid | −0.058 | −0.062 | −0.406 | 0.122 | 0.568 | 0.406 |

| Policy weakening | −0.238 | 0.166 | 0.068 | −0.221 | −0.020 | 0.149 |

| Natural disaster | −0.068 | −0.572 | 0.054 | 0.005 | −0.049 | 0.163 |

| Emergencies | −0.271 | 0.191 | 0.164 | 0.016 | −0.106 | 0.123 |

| Health condition | 0.115 | −0.095 | −0.250 | 0.576 | −0.334 | 0.017 |

| The probability of unemployment | 0.136 | −0.051 | 0.192 | 0.050 | −0.573 | 0.296 |

| Participatory right | 0.231 | 0.039 | 0.035 | −0.019 | 0.215 | 0.213 |

| Number | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | −0.414 | −0.212 | 0.700 | −0.115 | 0.019 | 0.811 | −0.118 |

| 13 | 0.243 | 0.163 | 0.796 | −0.410 | 0.282 | 0.888 | 0.207 |

| 20 | −0.244 | −0.358 | 0.303 | 0.399 | −0.165 | 0.868 | −0.068 |

| 22 | −0.426 | −0.245 | 0.773 | −0.300 | 0.334 | 0.984 | −0.108 |

| 30 | 0.251 | 0.268 | 0.505 | 0.505 | −0.397 | 0.888 | 0.215 |

| 35 | −0.343 | −0.269 | 0.758 | −0.414 | 0.206 | 0.937 | −0.090 |

| 56 | −0.321 | −0.152 | 0.869 | −0.192 | 0.233 | 1.095 | −0.042 |

| 68 | −0.241 | −0.160 | 0.360 | 0.666 | 0.052 | 1.096 | −0.010 |

| 117 | −0.418 | −0.268 | 0.756 | −0.300 | 0.341 | 0.941 | −0.110 |

| 119 | −0.281 | −0.093 | 0.617 | −0.063 | 0.181 | 0.802 | −0.046 |

| 173 | −0.338 | −0.162 | 0.421 | 0.620 | −0.086 | 0.872 | −0.066 |

| 174 | −0.357 | −0.194 | 0.657 | −0.286 | 0.294 | 1.183 | −0.074 |

| 179 | 0.334 | 0.258 | 0.317 | 0.386 | −0.244 | 0.887 | 0.237 |

| 181 | −0.133 | 0.256 | 0.288 | 0.466 | −0.091 | 0.735 | 0.040 |

| 183 | −0.034 | 0.157 | 0.662 | −0.304 | 0.063 | 1.135 | 0.085 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.-b.; Zhao, J.-h.; Yao, R.; Zhao, R.-t.; Li, Y. Risk of Poverty Returning to the Tibetan Area of Gansu Province in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811268

Wang Y-b, Zhao J-h, Yao R, Zhao R-t, Li Y. Risk of Poverty Returning to the Tibetan Area of Gansu Province in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811268

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yao-bin, Jin-hang Zhao, Rong Yao, Rui-tao Zhao, and Ying Li. 2022. "Risk of Poverty Returning to the Tibetan Area of Gansu Province in China" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811268

APA StyleWang, Y.-b., Zhao, J.-h., Yao, R., Zhao, R.-t., & Li, Y. (2022). Risk of Poverty Returning to the Tibetan Area of Gansu Province in China. Sustainability, 14(18), 11268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811268