Ecosystems of Collaboration for Sustainability-Oriented Innovation: The Importance of Values in the Agri-Food Value-Chain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

‘Economic issues include the incomes and livelihoods of producers and others involved in the network, employment, and local economic development, particularly in rural areas. Social issues include labour rights and the safety of workers, consumer health, food culture, and the accessibility, availability, and affordability of nutritious food (food security). Environmental impacts of food production, processing, packaging, distribution, and consumption, in turn, have to do with the use of resources and with pollution and damage to the soil, water, and air (including greenhouse gas emissions), biodiversity and ecosystems, and animal welfare’[9] (p. 65).

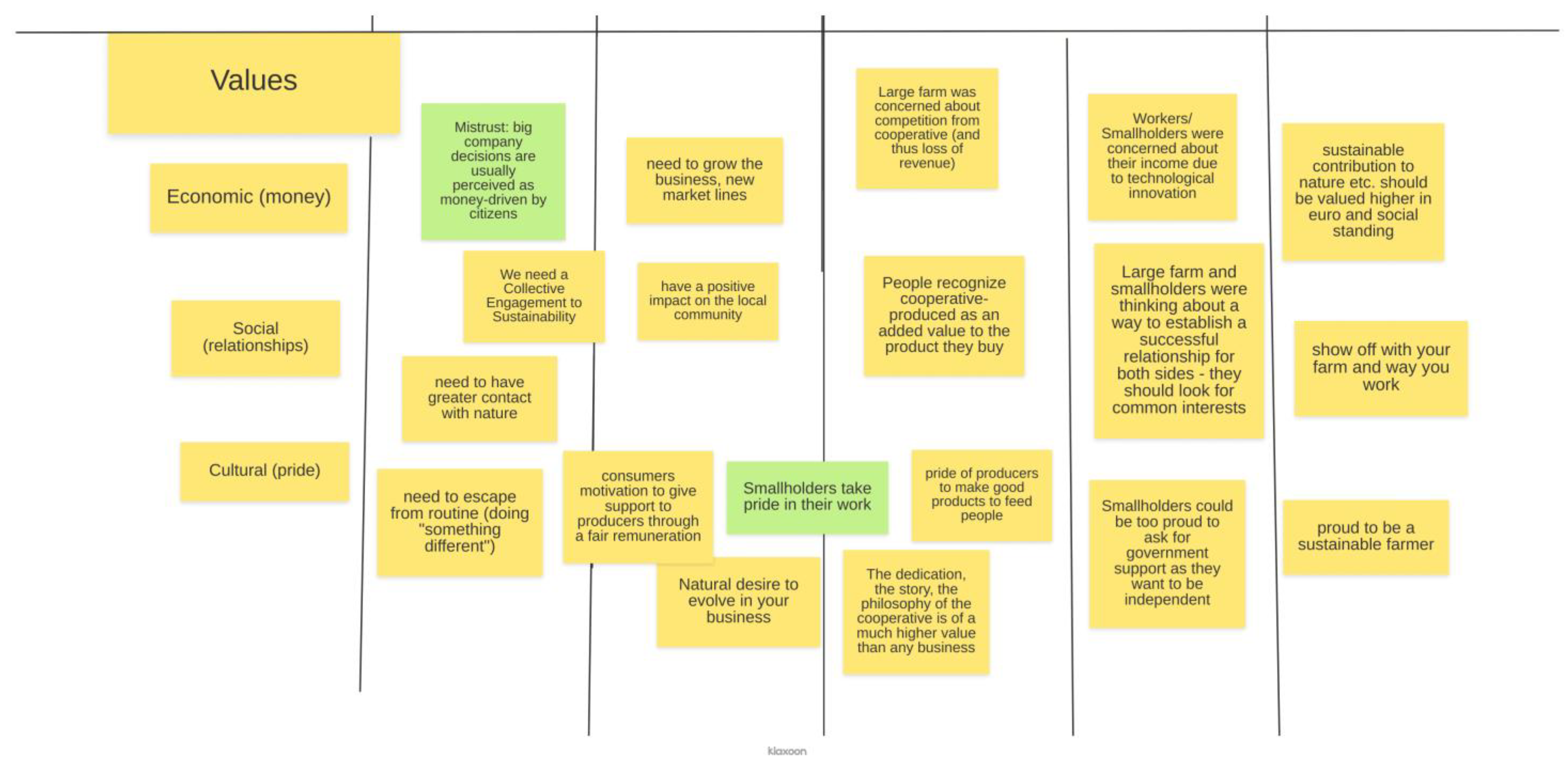

2. Values and SOI

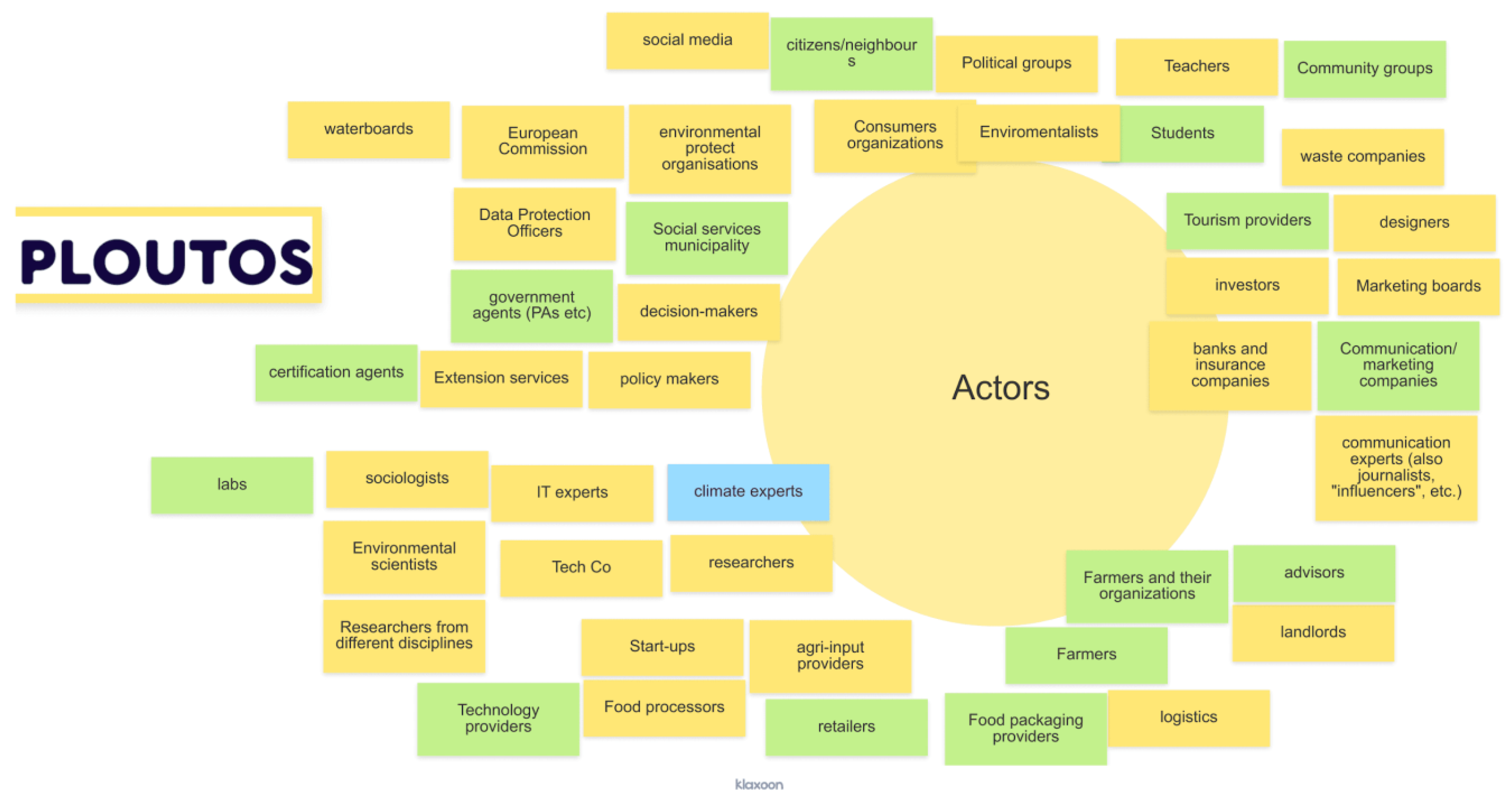

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. FGs1 (Vignettes and Brainstorming)

4.1.1. Economic Values

- Consumers: quality, precedence, transparency, price;

- Retailers: cost/profit, growth/diversification, and support for local producers;

- Producers: adequate income, collaboration, competitiveness;

- Authorities: adequate income, economic balance and fair trade;

- Advisors: value for money and quality.

4.1.2. Social Values

- Consumers: ethical consumption, health, tradition, and local values/cohesion;

- Retailers: collaboration and local support;

- Producers: inclusion, tradition and kin;

- Authorities: community commitment, family, guilt and shame about harming others;

- Advisors: change, cultural life and mutual learning.

4.1.3. Cultural Values

- Consumers: loyalty, trust, honesty, diversity, innovation;

- Retailers: innovation, prestige, tradition, diversity;

- Producers: pride, honour, prestige, tradition, loyalty, trust, independence/autonomy;

- Authorities: prestige, tradition and loyalty;

- Advisors: prestige and pride.

4.1.4. Enablers

- Consumers: described as mostly motivated by ethical and health-based decisions;

- Retailers: identified also as taking ethical considerations but mostly identifying market opportunities in sustainable products;

- Producers: mostly described as driven by the prestige of innovation, for their participation in wider networks, but also as motivated by new opportunities in the market;

- Authorities: enablers were described as deriving from organisational culture, opportunities for collaboration, and impact of development;

- Advisors: the enablers were described as a strong innovative ecosystem and good connections, mutual interests among stakeholders, desire to change and practical knowledge.

4.1.5. Hindrances

- Consumers: unrealistic expectations on price and the force of habit;

- Retailers: lack of market opportunities, cost/benefit;

- Producers: habit, lack of time/resources to spend on innovation, uncertainty;

- Authorities: unsuitable regulations, conflict of interests, distrust of people, lack of expertise or knowledge;

- Advisors: lack of trust, lack of transparency, and lack of skills.

4.2. FGs2 (Storyboarding)

4.2.1. Cross-Themes

- Ideas of fairness, transparency, honesty, equal opportunities and empathy underpin the importance given to trust across the agri-food value-chain. These values are linked by participants to the need for accurate information, effective communication, and for mutual understanding between actors.

- The ethical dimensions of production/consumption (animal welfare, environmental sustainability, supporting local produce, etc.) were very prominent for participants; although adequate income, good price and a margin of profit are important considerations, they didn’t represent the sole drivers of decision-making.

- Among the challenges, lack of information or skills, an inadequate system of incentives, and lack of support (financial, legal, market) were identified by participants as threatening the viability of SOI.

- The solutions explored implied the resourceful use of existing opportunities; technological, organisational and behavioural innovations; and increased collaboration between actors across the agri-food value-chain.

4.2.2. Leverages

- When put in dialogue with one another, and in an environment fostering collaboration, complementarities between actors contributed to envisioning possible sustainable innovations to address common, real-life problems.

- Synergies between producers and consumers, consumers and retailers, the combination of local and external knowledge and expertise, provided a wealth of SOIs.

- It is particularly important to emphasise that although technological innovation played an important role in some stories, many of the solutions explored by participants required changes in collaboration patterns among actors, changes in behaviour or in organisational culture.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Actor | Country | Gender |

|---|---|---|

| Consumers | Greece | Male |

| Food Industry | Cyprus | Male |

| Cyprus | Male | |

| UK | Female | |

| UK | Male | |

| France | Male | |

| Italy | Female | |

| Spain | Female | |

| Greece | Male | |

| Advisor | Italy | Female |

| Cyprus | Male | |

| Greece | Female | |

| Greece | Male | |

| North Macedonia | Male | |

| Farmer | Spain | Female |

| Ireland | Male | |

| France | Male | |

| Retail | Spain | Male |

| Spain | Male | |

| Netherlands | Male | |

| Tourism | Ireland | Male |

| Ireland | Female | |

| Spain | Female | |

| Spain | Female | |

| Spain | Male | |

| Research | Netherlands | Female |

| Spain | Male | |

| Spain | Female | |

| Belgium | Female | |

| Spain | Female | |

| Spain | Female | |

| Spain | Male | |

| Cyprus | Male | |

| Netherlands | Male | |

| Netherlands | Male | |

| North Macedonia | Female | |

| Ireland | Female | |

| Spain | Female | |

| Development Sector | Spain | Female |

| Spain | Female | |

| Spain | Female | |

| Spain | Male | |

| Government | Netherlands | Male |

| Netherlands | Female | |

| Cyprus | Female | |

| Ireland | Female | |

| Cyprus | Male | |

| Netherlands | Female | |

| Netherlands | Male | |

| Ireland | Male | |

| Finance Sector | Ireland | Male |

| Spain | Female | |

| Netherlands | Male |

Appendix B

| Actor | Economic Values | Social Values | Cultural Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumers |

|

|

|

| Retailers |

|

|

|

| Producers |

|

|

|

| Authorities |

|

|

|

| Advisors |

|

|

|

Appendix C

| Actor | Values |

|---|---|

| Producer |

|

| Consumer |

|

| Retailer |

|

| Tourism Operator |

|

| Authorities |

|

| Advisors |

|

| Researchers |

|

| Marketing consultant |

|

| Environmentalist |

|

| Innovation broker |

|

| Banker |

|

| Social media influencer |

|

Appendix D

References

- Friedmann, H. The political economy of food: A global crisis. New Left Rev. 1993, 197, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, T.; Barling, D.; Caraher, M. Food Policy: Integrating Health, Environment and Society; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Giménez, E.; Shattuck, A. Food crises, food regimes and food movements: Rumblings of reform or tides of transformation? J. Peasant. Stud. 2011, 38, 109–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Ploeg, J. Farmers’ upheaval, climate crisis and populism. J. Peasant Stud. 2020, 47, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.; Van Dusen, D.; Lundy, J.; Gliessman, S. Integrating social, environmental, and economic issues in sustainable agriculture. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 1991, 6, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxey, L. Can we sustain sustainable agriculture? Learning from small-scale producer-suppliers in Canada and the UK. Geogr. J. 2006, 172, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Squaring the circle? Some thoughts on the idea of sustainable development. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 48, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilbery, B.; Maye, D. Food supply chains and sustainability: Evidence from specialist food producers in the Scottish/English borders. Land Use Policy 2005, 22, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forssell, S.; Lankoski, L. The sustainability promise of alternative food networks: An examination through “alternative” characteristics. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello, S.; Yoon, E. Examining drivers of sustainable innovation. Int. J. Bus. Strategy 2008, 8, 164–169. [Google Scholar]

- Bos-Brouwers, H. Corporate sustainability and innovation in SMEs: Evidence of themes and activities in practice. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, M.; Magrini, M.; Triboulet, P. Transition agroécologique, innovation et effets de verrouillage: Le rôle de la structure organisationnelle des filières. Cah. Agric. 2012, 21, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale, A.; Eriksen, S.; Taylor, M.; Forsyth, T.; Pelling, M.; Newsham, A.; Boyd, E.; Brown, K.; Harvey, B.; Jones, L.; et al. Beyond Technical Fixes: Climate solutions and the great derangement. Clim. Dev. 2020, 12, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cillo, V.; Petruzzelli, A.; Ardito, L.; del Giudice, M. Understanding sustainable innovation: A systematic literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J. Behaviour and Sustainability Oriented Innovations in the Agri-Food Sector: A Structured, Semi-Systematic Review; Ploutos Working Document; TEAGASC: Dublin, Ireland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Feather, N. Values in Education and Society; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann, M.; Theuvsen, L. Value structures determining community supported agriculture: Insights from Germany. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.; Bilsky, W. Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, R.; Ester, P. Values and Work Empirical Findings and Theoretical Perspective. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 1999, 48, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Forstater, M.; Zadek, S.; Guang, Y.; Yu, K.; Hong, C.; George, M. Corporate Responsibility in African Development: Insights from an Emerging Dialogue; Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative, Working Paper 60; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tregear, A. Progressing knowledge in alternative and local food networks: Critical reflections and a research agenda. J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, J.; Howley, P. The accidental environmentalists: Factors affecting farmers’ adoption of pro-environmental activities in England and Ontario. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barham, E. Towards a theory of values-based labelling. Agric. Hum. Values 2002, 19, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, C. Social embeddedness and relations of regard: Alternative ‘good food’ networks in south-west Ireland. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K. Local and green, global and fair: The ethical foodscape and the politics of care. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 1852–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-González, I.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz-Molina, M. Ethically Minded Consumer Behavior, Retailers’ Commitment to Sustainable Development, and Store Equity in Hypermarkets. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiffoleau, Y. Dynamique des identités collectives dans le changement d’échelle des circuits courts alimentaires. Rev. Française Socio-Écon. 2017, 18, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klerkx, L.; Aarts, N.; Leeuwis, C. Adaptive management in agricultural innovation systems: The interactions between innovation networks and their environment. Agric. Syst. 2010, 103, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; Proctor, A. Beyond fragmentation and disconnect: Networks for knowledge exchange in the English land management advisory system. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.; Becker, A. The Use of Vignettes in Survey Research. Public Opin. Q. 1978, 42, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, J. The Vignette Technique in Survey Research. Sociology 1987, 21, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.; While, A. Methodological issues surrounding the use of vignettes in qualitative research. J. Interprof. Care 1998, 12, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever Happened to Qualitative Description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. What’s in a Name? Qualitative Description Revisited. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, R.; Macken-Walsh, A. An actor-oriented approach to understanding dairy farming in a liberalised regime: A case study of Ireland’s New Entrants’ Scheme. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, D. The strange history of the economic agent. New Sch. Econ. Rev. 2004, 1, 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- Szmigin, I.; Carrigan, M.; McEachern, M. The conscious consumer: Taking a flexible approach to ethical behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparcia, J. Innovation and networks in rural areas. An analysis from European innovative projects. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, T.; Gorman, M. Exploring the concept of farm household innovation capacity in relation to farm diversification in policy context. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 46, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Fielke, S.; Bayne, K.; Klerkx, L.; Nettle, R. Navigating shades of social capital and trust to leverage opportunities for rural innovation. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Yihuan, W.; Long, N. Farmer Initiatives and Livelihood Diversification: From the Collective to a Market Economy in Rural China. J. Agrar. Change 2009, 9, 175–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, S.; Swan, J. Trust and inter-organizational networking. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 1287–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Bui, S.; Marsden, T. Redefining power relations in agrifood systems. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotz, S.; Gravely, E.; Mosby, I.; Duncan, E.; Finnis, E.; Horgan, M.; LeBlanc, J.; Martin, R.; Neufeld, H.; Nixon, A.; et al. Automated pastures and the digital divide: How agricultural technologies are shaping labour and rural communities. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, I. Bridging the rural-urban divide in social innovation transfer: The role of values. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 1261–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Clarke, I. Culture, consumption and choice: Towards a conceptual relationship. J. Consum. Stud. Home Econ. 1998, 22, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Shiu, E. Ethics in consumer choice: A multivariate modelling approach. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1485–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D.; Hillier, D. What’s in store? Retail marketing and corporate social responsibility. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2007, 25, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrero, I.; Valor, C. CSR-labelled products in retailers’ assortment: A comparative study of British and Spanish retailers. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gutiérrez, J.A.; Macken-Walsh, Á. Ecosystems of Collaboration for Sustainability-Oriented Innovation: The Importance of Values in the Agri-Food Value-Chain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11205. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811205

Gutiérrez JA, Macken-Walsh Á. Ecosystems of Collaboration for Sustainability-Oriented Innovation: The Importance of Values in the Agri-Food Value-Chain. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11205. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811205

Chicago/Turabian StyleGutiérrez, José A., and Áine Macken-Walsh. 2022. "Ecosystems of Collaboration for Sustainability-Oriented Innovation: The Importance of Values in the Agri-Food Value-Chain" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11205. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811205

APA StyleGutiérrez, J. A., & Macken-Walsh, Á. (2022). Ecosystems of Collaboration for Sustainability-Oriented Innovation: The Importance of Values in the Agri-Food Value-Chain. Sustainability, 14(18), 11205. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811205