The Impact of Land Fragmentation in Rice Production on Household Food Insecurity in Vietnam

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measuring Food Security

2.2. Measuring the Effect of Land Fragmentation on Household Food Insecurity

- t = 2012, 2014, 2016

- i = 1, …, n

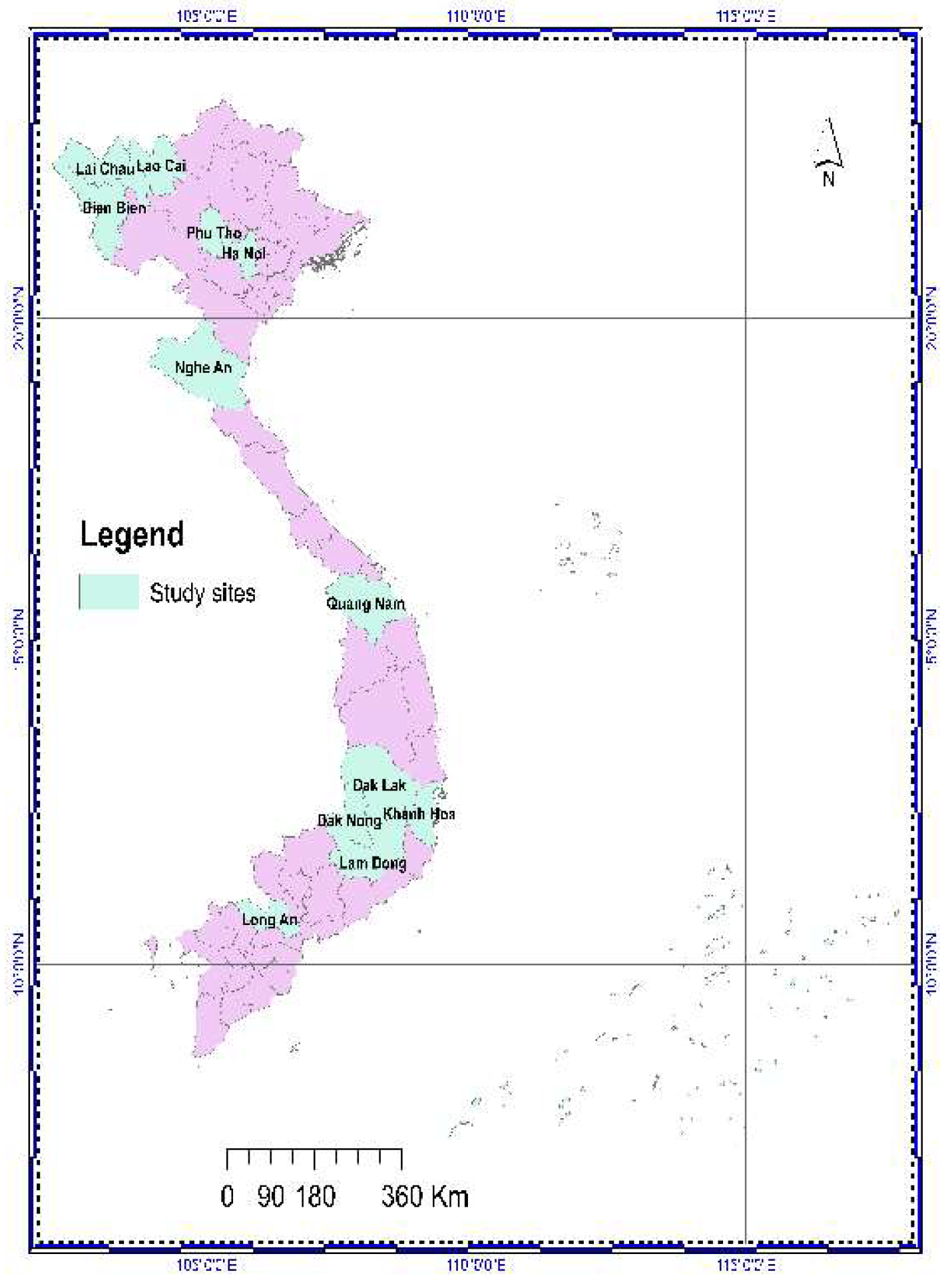

3. Data Sources

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.2. Estimation Results

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Phan, N.T.; Pabuayon, I.M.; Kien, N.D.; Dung, T.Q.; An, L.T.; Dinh, N.C. Factors Driving the Adoption of Coping Strategies to Market Risks of Shrimp Farmers: A Case Study in a Coastal Province of Vietnam. Asian J. Agric. Rural Dev. 2022, 12, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.T.; Thai, T.Q.N.; Tran, V.T.; Pham, T.P.; Doan, Q.C.; Vu, K.H.; Doan, H.G.; Bui, Q.T. Land Consolidation at the Household Level in the Red River Delta, Vietnam. Land 2020, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSO. Vietnam Statiscal Yearbook 2021; General Statistics Office, Statistical Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Embassy of The Netherlands in Hanoi and Consulate General in Ho Chi Minh City. Agriculture in Vietnam. Available online: https://www.rvo.nl/sites/default/files/2017/11/factsheet-agriculture-in-vietnam.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Agboola, W.L.; Yusuf, S.A.; Salman, K.K. Determinants of preference for land management practices among food crop farmers in North-Central Nigeria. Niger. Agric. J. 2019, 49, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, T.Q.; Vu, H. Van Land fragmentation and household income: First evidence from rural Vietnam. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Transforming Vietnamese Agriculture: Gaining More for Less; Vietnam Development Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/24375 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Thi, N.P.; Kappas, M.; Faust, H. Impacts of agricultural land acquisition for urbanization on agricultural activities of affected households: A case study in Huong Thuy town, Thua Thien Hue province, Vietnam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaian, P.; Guri, F.; Rajcaniova, M.; Drabik, D.; y Paloma, S.G. Land fragmentation and production diversification: A case study from rural Albania. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippenberg, E.; Jolliffe, D.; Hoddinott, J. Land Fragmentation and Food Insecurity in Ethiopia. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 102, 1557–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSO. Vietnam Statiscal Yearbook 2018; General Statistics Office, Statistical Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, L.; Nguyen, H.-T.-M.; Kompas, T.; Dang, K.; Bui, T. Rice land protection in a transitional economy: The case of Vietnam. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xie, H.; Yao, G. Impact of land fragmentation on marginal productivity of agricultural labor and non-agricultural labor supply: A case study of Jiangsu, China. Habitat Int. 2019, 83, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lon, Y.; Hotta, K.; Nanseki, T. Impact of Land Fragmentation on Economic Feasibility of Farmers in Rice-Based Farming System in Myanmar. Fac. Agric. Kyushu Univ. 2011, 56, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Lu, D.; Yan, J. Evaluating the impact of land fragmentation on the cost of agricultural operation in the southwest mountainous areas of China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niroula, G.S.; Thapa, G.B. Impacts of land fragmentation on input use, crop yield and production efficiency in the mountains of Nepal. L. Degrad. Dev. 2007, 18, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.P.; Kumar, A.; Singh, K.M.; Chandra, N.; Bharati, R.C.; Kumar, U.; Kumar, P. Farm Size and Productivity Relationship in Smallholder Farms: Some empirical evidences from Bihar, India. J. Community Mobilization Sustain. Dev. 2018, 13, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.; Zhu, F.; Chen, F.; Yu, M.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y. Assessing the impacts of land consolidation on agricultural technical efficiency of producers: A survey from Jiangsu Province, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholo, T.C.; Fleskens, L.; Sietz, D.; Peerlings, J. Land fragmentation, climate change adaptation, and food security in the Gamo Highlands of Ethiopia. Agric. Econ. 2019, 50, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippenberg, E.; Jolliffe, D.; Hoddinott, J. Land Fragmentation and Food Insecurity in Ethiopia; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.Q.; Vu, H. The impact of land fragmentation on food security in the North Central Coast, Vietnam. Asia Pacific Policy Stud. 2021, 8, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholo, T.C.; Fleskens, L.; Sietz, D.; Peerlings, J. Is land fragmentation facilitating or obstructing adoption of climate adaptation measures in Ethiopia? Sustainability 2018, 10, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.C.; Subandoro, A. Measuring Food Security Using Household Expenditure Surveys; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; ISBN 9780896297678. [Google Scholar]

- Jackman, S. Models for Ordered Outcomes. Political Sci. C 2000, 200, 1–20. Available online: https://web.stanford.edu/class/polisci203/ordered.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Duc, K.N.; Ancev, T.; Randall, A. Farmers’ choices of climate-resilient strategies: Evidence from Vietnam. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nonvide, G.M.A. Irrigation adoption: A potential avenue for reducing food insecurity among rice farmers in Benin. Water Resour. Econ. 2018, 24, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B. Household Assets and Food Security: Evidence from the Survey of Program Dynamics. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2011, 32, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah; Zhou, D.; Shah, T.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, W.; Din, I.U.; Ilyas, A. Factors affecting household food security in rural northern hinterland of Pakistan. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Han, X.; Elahi, E.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X. Internet Access and Nutritional Intake: Evidence from Rural China. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korir, L.; Rizov, M.; Ruto, E.; Walsh, P.P. Household Vulnerability to Food Insecurity and the Regional Food Insecurity Gap in Kenya. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, H.T.; Nguyen, T.T. Cropland rental market and farm technical efficiency in rural Vietnam. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidisha, S.H.; Khan, A.; Imran, K.; Khondker, B.H.; Suhrawardy, G.M. Role of credit in food security and dietary diversity in Bangladesh. Econ. Anal. Policy 2017, 53, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Guideline for Interpretation | Ordered Probit |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage of expenditure on food (%) (the total spending on food in the total income of a household) | >75: very high food insecurity | 1 |

| >65: high food insecurity | 2 | |

| >50: medium food insecurity | 3 | |

| <50: low food insecurity | 4 (Base) |

| Provinces | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ha Tay | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.53 |

| Lao Cai | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.40 |

| Phu Tho | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.59 |

| Lai Chau | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.52 |

| Dien Bien | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.44 |

| Nghe An | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.52 |

| Quang Nam | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.47 |

| Khanh Hoa | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.29 |

| Dak Lak | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.31 |

| Dak Nong | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.27 |

| Lam Dong | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.24 |

| Long An | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.36 |

| Total | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.48 |

| Variables | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | All | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | |

| Outcome variables | ||||||||

| 1= Very high food insecurity; 2= High level of food insecurity; 3 = Medium level of food insecurity; 4 = Low level of food insecurity | 3.613 | 0.798 | 3.752 | 0.789 | 3.797 | 0.637 | 3.721 | 0.712 |

| Explanatory variables | ||||||||

| Fragmentation index | 0.511 | 0.287 | 0.471 | 0.287 | 0.454 | 0.285 | 0.479 | 0.287 |

| Farm and land characteristics | ||||||||

| Total cultivated area (m2) | 3350.045 | 5441.889 | 3298.191 | 5274.620 | 3148.765 | 4770.635 | 3265.667 | 5169.105 |

| Irrigation (% of plots irrigated) | 0.904 | 0.269 | 0.923 | 0.240 | 0.956 | 0.189 | 0.928 | 0.236 |

| Rice productivity (kg/m2) | 0.488 | 0.136 | 0.502 | 0.138 | 0.500 | 0.127 | 0.497 | 0.134 |

| Land quality (1 = lower average; 2 = average; 3 = higher average quality) | 1.940 | 0.351 | 1.991 | 0.303 | 1.994 | 0.282 | 1.975 | 0.314 |

| Household and farm characteristics | ||||||||

| Household labor size (persons) | 4.538 | 1.605 | 4.516 | 1.608 | 4.438 | 1.646 | 4.497 | 1.620 |

| Gender of household head (1 = Male) | 0.856 | 0.352 | 0.838 | 0.368 | 0.836 | 0.370 | 0.843 | 0.363 |

| Age of household head (years) | 49.514 | 12.763 | 51.105 | 12.675 | 52.627 | 12.593 | 51.082 | 12.736 |

| Education of household head (years) | 8.075 | 3.020 | 8.672 | 2.849 | 8.927 | 2.748 | 8.558 | 2.896 |

| Household assets (Number of assets) | 6.974 | 3.456 | 7.904 | 3.522 | 4.751 | 2.068 | 6.543 | 3.359 |

| Types of seed (1 = Hybrid seed from Vietnam) | 0.489 | 0.500 | 0.606 | 0.489 | 0.581 | 0.494 | 0.559 | 0.497 |

| Access to credit (1 = yes) | 0.621 | 0.485 | 0.664 | 0.473 | 0.940 | 0.238 | 0.741 | 0.438 |

| Socks (1 = Experienced illness, droughts, floods) | 0.496 | 0.500 | 0.408 | 0.492 | 0.336 | 0.473 | 0.413 | 0.493 |

| Number of extension officer visits (times/year) | 1.388 | 2.259 | 1.793 | 2.722 | 1.053 | 1.490 | 1.411 | 2.236 |

| Savings (1 = yes) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.841 | 0.366 | 0.865 | 0.342 | 0.902 | 0.297 |

| Access to the internet (1 = yes) | 0.233 | 0.423 | 0.268 | 0.443 | 0.449 | 0.498 | 0.317 | 0.465 |

| Levels of Household Food Insecurity | Land Fragmentation Index | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | Total | |

| Very high food insecurity | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.55 |

| High food insecurity | 0.56 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.50 |

| Medium food insecurity | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.47 |

| Low food insecurity | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.47 |

| Total | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.48 |

| Variables | Ordered Probit Model | CRE Ordered Probit Model |

|---|---|---|

| Fragmentation index | −0.362 *** | −0.558 *** |

| (−0.106) | (−0.198) | |

| Total cultivated area 1 | 0.105 *** | 0.095 ** |

| (−0.04) | (−0.042) | |

| Irrigation | 0.196 | 0.185 |

| (−0.124) | (−0.184) | |

| Rice productivity | 0.279 | 0.487 |

| (−0.25) | (−0.328) | |

| Land quality | 0.01 | 0.097 |

| (−0.096) | (−0.108) | |

| Household labor size 1 | 0.005 | −0.02 |

| (−0.072) | (−0.168) | |

| Gender of household head | −0.011 | −0.029 |

| (−0.082) | (−0.082) | |

| Age of household head 1 | 0.166 | 0.166 |

| (−0.114) | (−0.114) | |

| Education of household head 1 | 0.075 | 0.017 |

| (−0.067) | (−0.111) | |

| Household assets | 0.010 | 0.000 |

| (−0.009) | (−0.013) | |

| Types of Seed | −0.118 ** | −0.111 * |

| (−0.057) | (−0.057) | |

| Access to credit | 0.215 *** | 0.321 *** |

| (−0.067) | (−0.082) | |

| Socks | 0.003 | 0.028 |

| (−0.06) | (−0.078) | |

| Number of extension officer visit | −0.017 * | −0.013 |

| (−0.01) | (−0.014) | |

| Savings | 0.266 *** | 0.289 *** |

| (−0.089) | (−0.09) | |

| Access to the internet | 0.022 | 0.012 |

| (−0.063) | (−0.082) | |

| Within-household means | No | Yes |

| Observations | 2784 | 2784 |

| Variables | Very High Level of Food Insecurity (y = 1) | High Level of Food Insecurity (y = 2) | Medium Level of Food Insecurity (y = 3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ordered Probit Model | CRE Ordered Probit Model | Ordered Probit Model | CRE Ordered Probit Model | Ordered Probit Model | CRE Ordered Probit Model | |

| Fragmentation index | 0.0312 *** | 0.0479 *** | 0.0155 *** | 0.0238 *** | 0.0413 *** | 0.0635 *** |

| (0.0095) | (0.0174) | (0.0048) | (0.0088) | (0.0122) | (0.0225) | |

| Total cultivated area 1 | −0.0090 *** | −0.0081 ** | −0.0045 *** | −0.0040 ** | −0.0120 *** | −0.0108 ** |

| (0.0035) | (0.0036) | (0.0017) | (0.0018) | (0.0045) | (0.0048) | |

| Irrigation | −0.0169 | −0.0158 | −0.0084 | −0.0079 | −0.0224 | −0.0210 |

| (0.0107) | (0.0159) | (0.0054) | (0.0079) | (0.0142) | (0.0210) | |

| Rice productivity | −0.0241 | −0.0418 | −0.0120 | −0.0208 | −0.0319 | −0.0554 |

| (0.0217) | (0.0284) | (0.0108) | (0.0140) | (0.0286) | (0.0374) | |

| Land quality | −0.0008 | −0.0083 | −0.0004 | −0.0041 | −0.0011 | −0.0111 |

| (0.0083) | (0.0093) | (0.0041) | (0.0046) | (0.0110) | (0.0123) | |

| Household labor size 1 | −0.0004 | 0.0017 | −0.0002 | 0.0009 | −0.0006 | 0.0023 |

| (0.0062) | (0.0144) | (0.0031) | (0.0072) | (0.0082) | (0.0191) | |

| Gender of household head | 0.0010 | 0.0025 | 0.0005 | 0.0012 | 0.0013 | 0.0033 |

| (0.0071) | (0.0070) | (0.0035) | (0.0035) | (0.0094) | (0.0093) | |

| Age of household head 1 | −0.0143 | −0.0143 | −0.0071 | −0.0071 | −0.0189 | −0.0189 |

| (0.0098) | (0.0099) | (0.0049) | (0.0049) | (0.0131) | (0.0131) | |

| Education of household head 1 | −0.0064 | −0.0014 | −0.0032 | −0.0007 | −0.0085 | −0.0019 |

| (0.0058) | (0.0095) | (0.0029) | (0.0047) | (0.0076) | (0.0126) | |

| Household assets | −0.0008 | 0.0000 | −0.0004 | 0.0000 | −0.0011 | 0.0000 |

| (0.0008) | (0.0011) | (0.0004) | (0.0006) | (0.0010) | (0.0015) | |

| Types of Seed | 0.0102 ** | 0.0095 * | 0.0051 ** | 0.0047 * | 0.0135 ** | 0.0126 * |

| (0.0049) | (0.0049) | (0.0025) | (0.0025) | (0.0065) | (0.0065) | |

| Access to credit | −0.0185 *** | −0.0275 *** | −0.0092 *** | −0.0137 *** | −0.0246 *** | −0.0365 *** |

| (0.0059) | (0.0073) | (0.0030) | (0.0037) | (0.0076) | (0.0092) | |

| Socks | −0.0003 | −0.0024 | −0.0001 | −0.0012 | −0.0003 | −0.0031 |

| (0.0052) | (0.0067) | (0.0026) | (0.0033) | (0.0069) | (0.0089) | |

| Number of extension officer visit | 0.0014 * | 0.0011 | 0.0007 * | 0.0006 | 0.0019 * | 0.0015 |

| (0.0008) | (0.0012) | (0.0004) | (0.0006) | (0.0011) | (0.0016) | |

| Savings | −0.0230 *** | −0.0248 *** | −0.0114 *** | −0.0123 *** | −0.0305 *** | −0.0329 *** |

| (0.0079) | (0.0080) | (0.0040) | (0.0040) | (0.0102) | (0.0103) | |

| Access to the internet | −0.0019 | −0.0010 | −0.0010 | −0.0005 | −0.0025 | −0.0014 |

| (0.0054) | (0.0071) | (0.0027) | (0.0035) | (0.0072) | (0.0094) | |

| Within-household means | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Observations | 2784 | 2784 | 2784 | 2784 | 2784 | 2784 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Phan, N.T.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kien, N.D. The Impact of Land Fragmentation in Rice Production on Household Food Insecurity in Vietnam. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11162. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811162

Phan NT, Lee J-Y, Kien ND. The Impact of Land Fragmentation in Rice Production on Household Food Insecurity in Vietnam. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11162. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811162

Chicago/Turabian StylePhan, Nguyen Thai, Ji-Yong Lee, and Nguyen Duc Kien. 2022. "The Impact of Land Fragmentation in Rice Production on Household Food Insecurity in Vietnam" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11162. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811162

APA StylePhan, N. T., Lee, J.-Y., & Kien, N. D. (2022). The Impact of Land Fragmentation in Rice Production on Household Food Insecurity in Vietnam. Sustainability, 14(18), 11162. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811162