Evaluating Actions to Improve Air Quality at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Setting

1.3. Study Aims and Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scoping and Identification of Air Quality Actions

2.2. Data Collection for Qualitative Assessement: Interviews with Subject Area Experts

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Procedure

2.2.3. Analysis

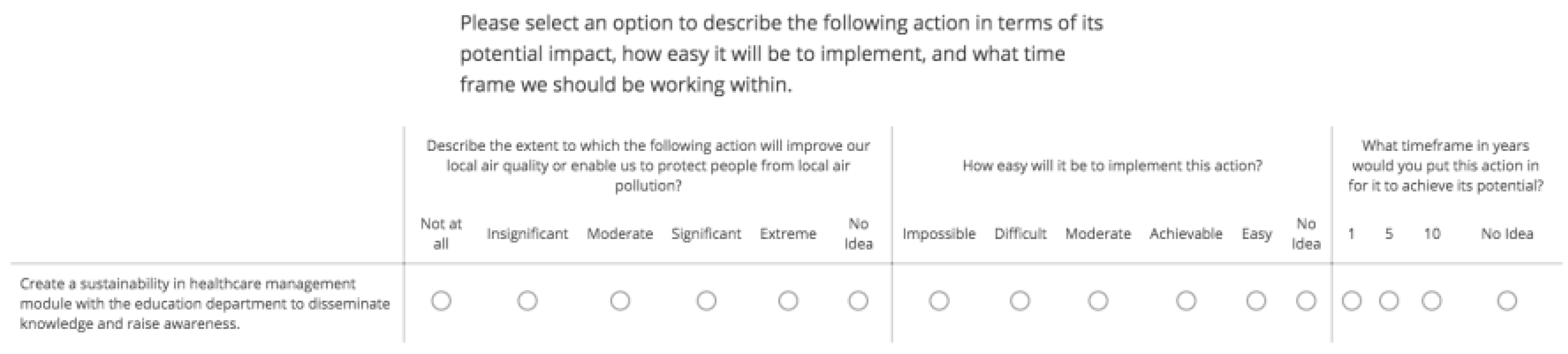

2.3. Data Collection for Quantitative Assessment

2.3.1. Participant Recruitment

2.3.2. Data Collection

- ‘Describe the extent to which the following action will improve our local air quality or enable us to protect people from local air pollution?’Answers are on a Likert scale with six options:

- Not at all

- Insignificant

- Moderate

- Significant

- Extreme

- No Idea

- ‘How easy will it be to implement the action?’With answers the Likert options:

- Impossible

- Difficult

- Moderate

- Achievable

- Easy

- No Idea

- ‘what time frame they would expect the action required to achieve its potential’With answers from:

- 1 Year

- 5 Years

- 10 Years

2.3.3. Analysis

2.4. Combining Interview and Survey Data

3. Results

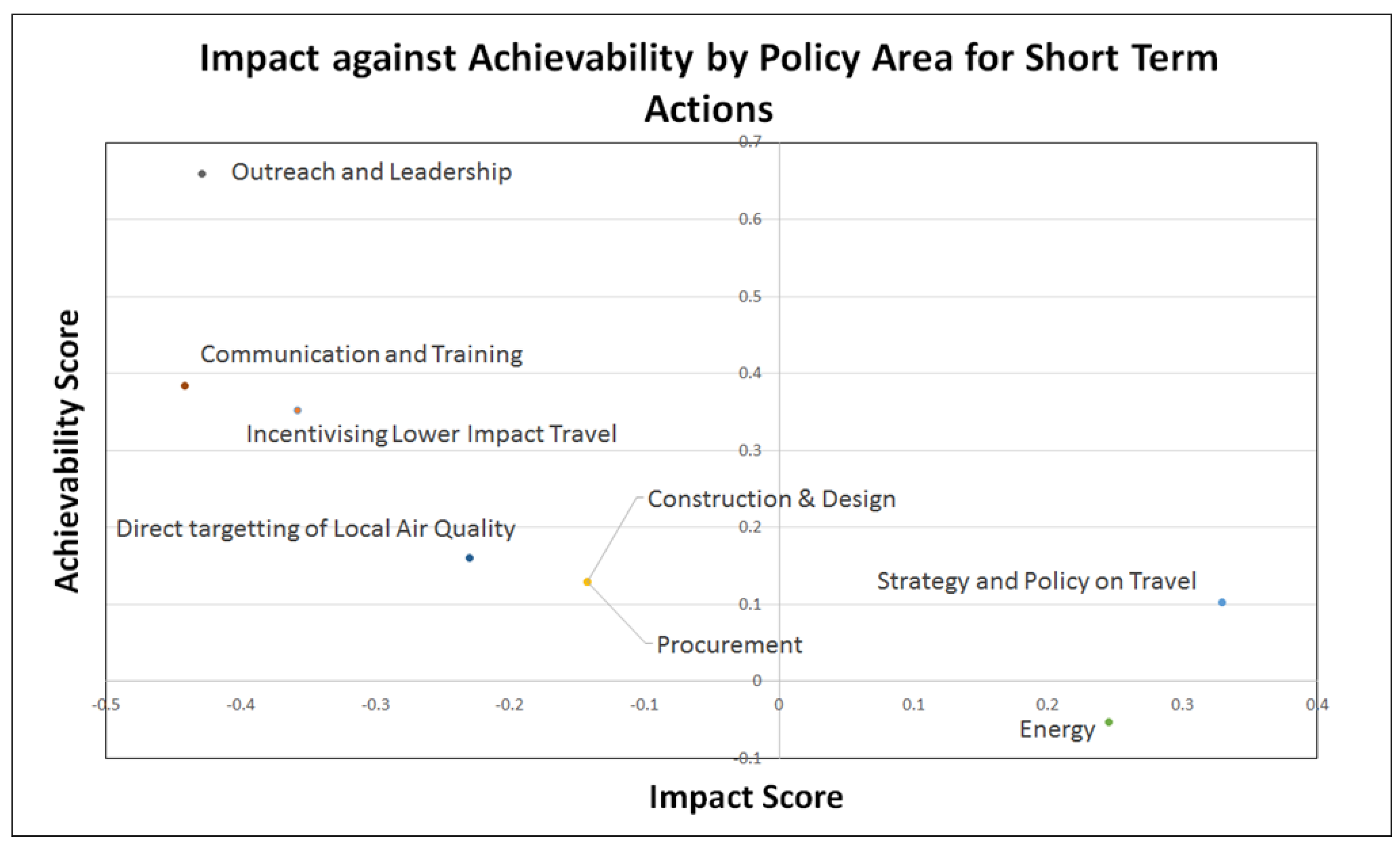

3.1. Comparison of Policy Areas in Short and Long Run

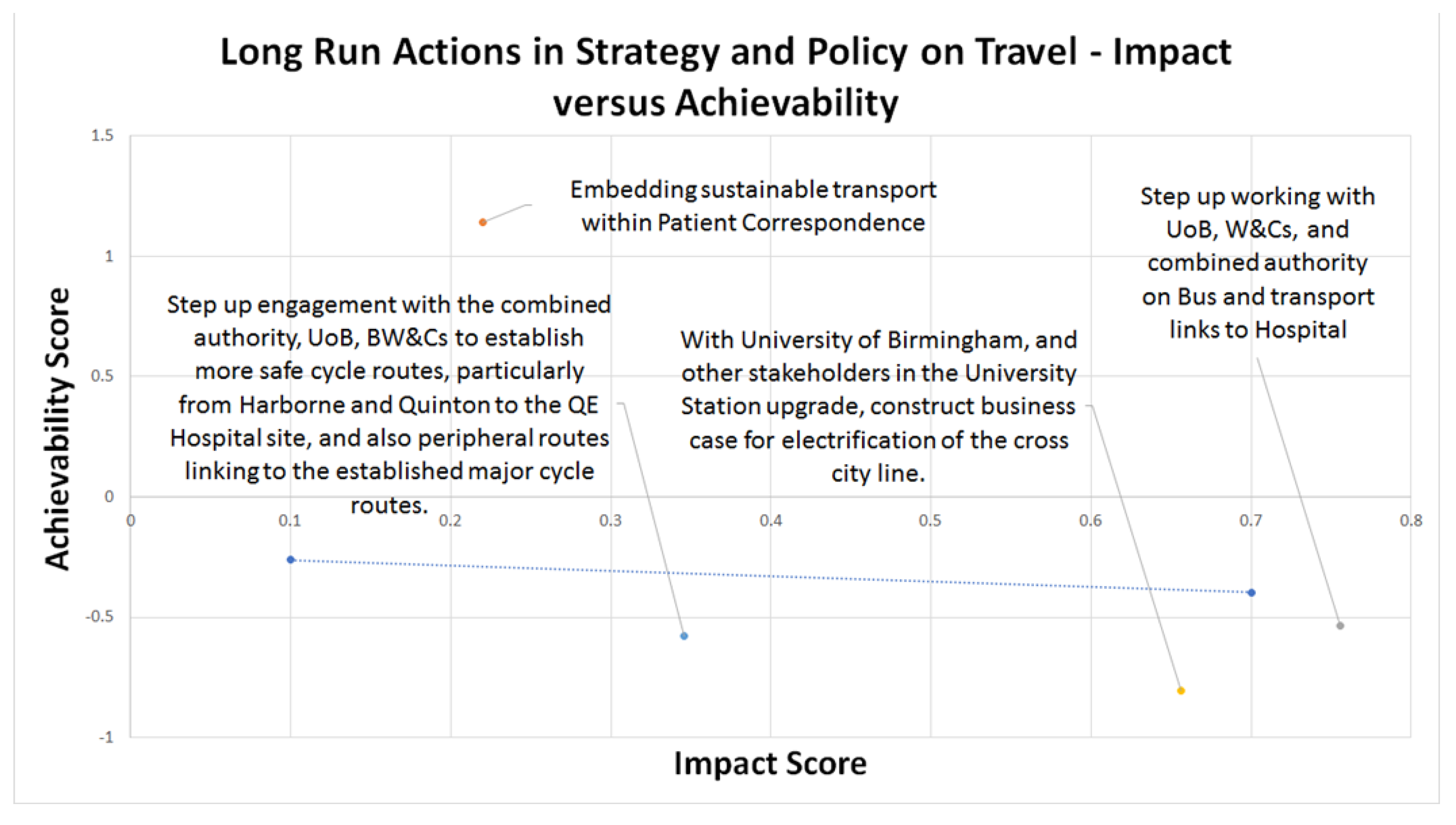

3.2. Strategy and Policy on Travel

“…the plan would be that, on a pathway, the patient wouldn’t need to go to see the GP, but would come in straight for diagnostic, and then straight to see the clinician for counselling and discussions around how we’re going to deal with their health care needs after having the diagnostics. So possibly take two to three appointments out of the system for each patient that comes through those pathways. So that’s a fairly big one.”

‘I have been working with some other trusts around their cycle parking facilities, some folks, you know, it’s normalizing it, making it feel normal and that you’re welcome to arrive by active means that you are given higher priority, that you have safe, secure cycle parking near to the entrance to the hospital.’

‘I didn’t know about this, where the cycle lanes were, and people that talk to me when we have casual conversations about, you know, you don’t live very far, you could cycle in, going: what and just get knocked off my bike. There aren’t any cycle lanes. So that’s the perception.’

‘But, they seem to be weirdly discouraging people from taking that bus as a route to get to work because it’s a really strange thing… you’d expect a bus service provided to get you into the QEHB, would think about having lots of buses around the period of eight o’clock to nine to get people in work. But for some reason, inexplicably, this bus service, the one bus service that gets you from Mosley into the QEHB has this inexplicable 50 min pause where no buses run. So between 08.00 a.m. and 08.53 a.m., there is no bus that gets you into the QEHB. So you’re either extremely early or very late into work.’

‘But at the moment the way patients receive information in their patient letter, it feels predominantly focused around accessing car parking and not actually public transport. Again, we’re just currently moving through switching from paper correspondence with patients to electronic correspondence and we’re hoping to kind of rejig the patient letter there so that we can actually embed links so that you could say, if you want to access the QEHB site by public transport, how would you go about doing it?’

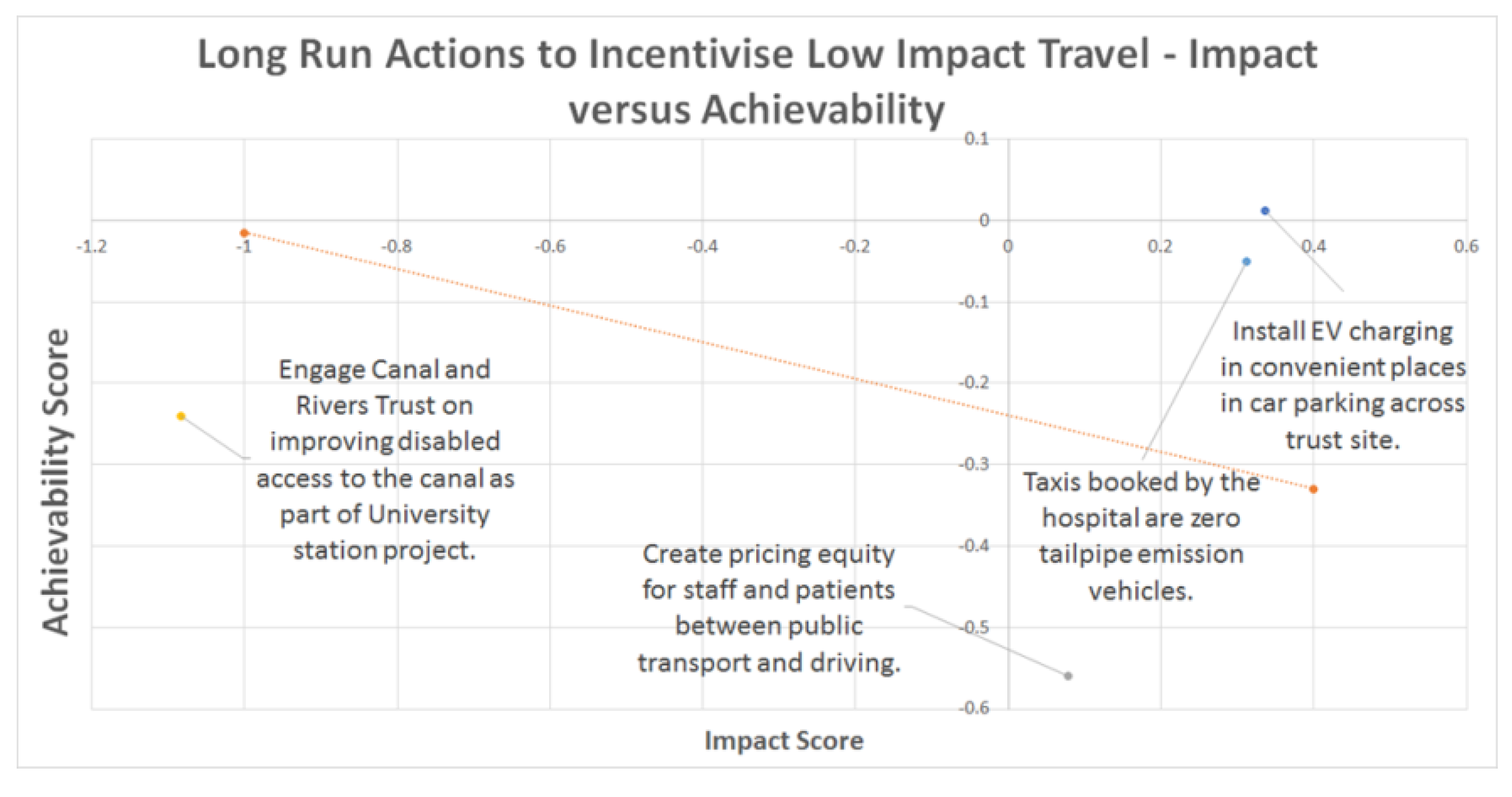

3.3. Incentivising Lower Impact Travel

‘I think we could have better facilities, more of them and more secure facilities, for cycling and they would be used, and that would help to increase sustainable travel. I don’t think we do very well.’

…

‘But again, while we’ve still got an issue with security that’s a really big problem that needs to be dealt with. It’s affecting our staff already. One person down here just got a new bike through the cycle to work scheme. It got stolen within a week.’

‘I think that is indicative of the issue that you’re facing here in that any move towards improvement is just going to be fraught with just massive bureaucracy at times. It can be paralyzing…’

‘the price of a permit is still cheaper than the cost of a travel permit ticket on the railway or the bus. At the very least we should aim for parity, if not making car parking more expensive… it is actually less than a bus permit. It can’t be right that it’s cheaper to park than to come by public transport.’

A key barrier identified for implementing these changes was concern regarding staff recruitment and retention, notably consultants/highly skilled staff who are in high demand.

‘[X] said to me about the car parking, that [they] didn’t want all the consultants to go work for a different hospital because they couldn’t park their cars.’

‘It’s not particularly easy to nudge people out of their cars. To a certain extent you have to force it. And the fact that we’ve reduced the number of car parking permits, we’ve started to tier staff as to their importance and whether they get a parking permit or not, is beginning to bring some of that enforcement, but once you start enforcing things, then we have the downside of that we lose staff goodwill and we can’t really afford that at the moment.’

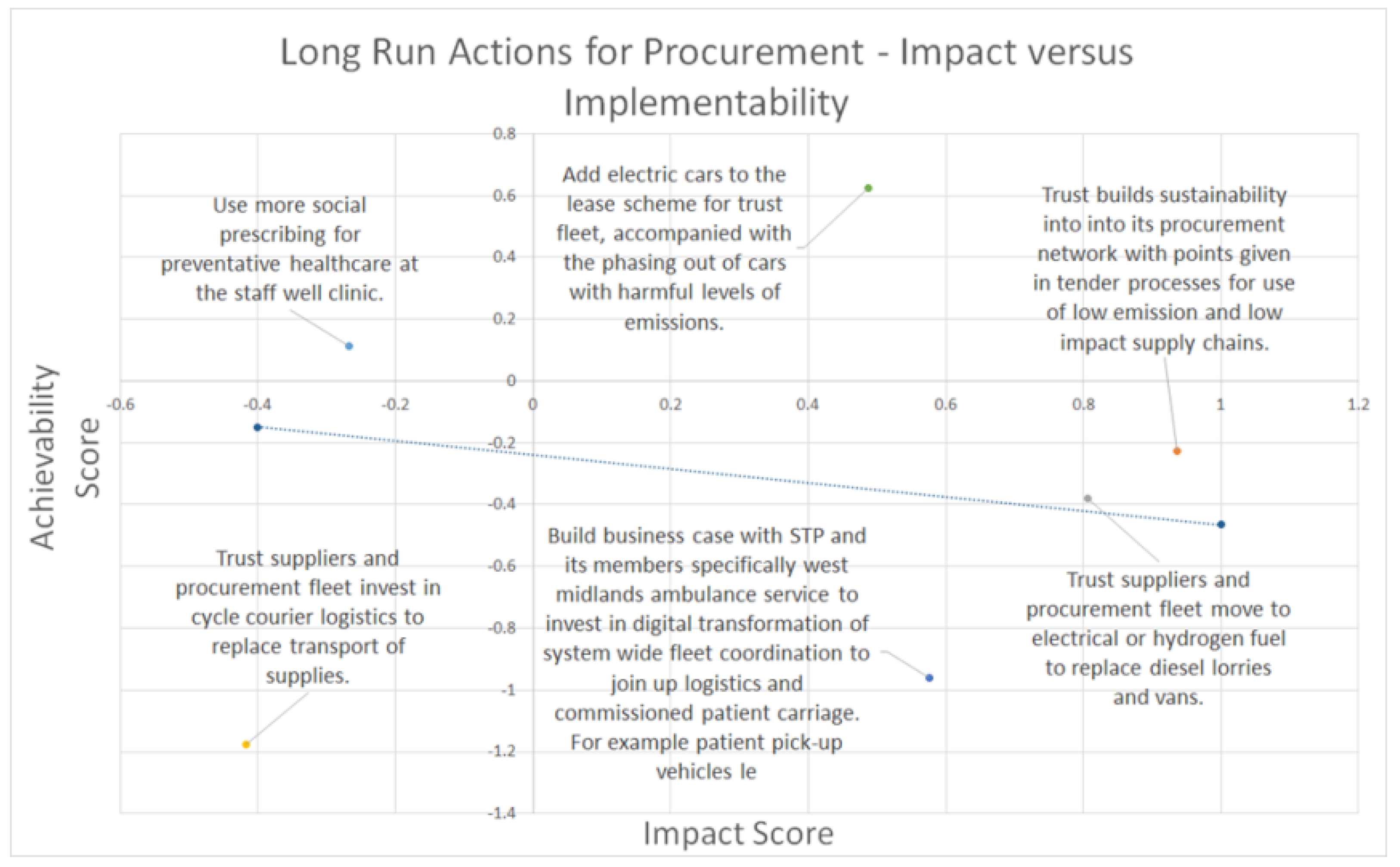

3.4. Procurement

‘I think the potential is a bit limited. And also a lot of the goods tend to be too bulky. Post tends to come into this site, there’s a post room, so it’s delivered there and distributed just on foot. So there’s no vehicles really used, so I think it’d be limited.’

‘So we have a very significant voice in the West Midlands procurement network in a way that, you think UHB was before, but actually we weren’t… So we’ve increased our voice and so there are things we can influence and I think it’s, it’s coming at a time that the national level is also incredibly interested in sustainability as well. So I think our bigger voice and the national level also recognizes that value for money is very important, but we can also use our purchasing power in a slightly different way. The STP, for example, did quite a bit of work around the social value policy, drawing on some of the learning from local authorities that perhaps do this and their suppliers tend to be more local than the NHS, so sometimes it’s slightly different. But we did quite a bit of work just to kind of start to understand what good looks like across all our partners for procurement for social value.’

‘Our primary purpose as an organization is to deliver healthcare, safe, high quality, effective healthcare to patients. So that needs to be our primary focus. To do that you need to have money. So that is secondary and then you’re kind of into the tertiary elements, which is how we do that? I think sustainability sits in that kind of tertiary element of how we do it. How do we do this effectively? How do we do this in a sustainable way? How do we do this with minimum waste? All those kinds of things. If we minimize the waste that should mean that we’ve got more money to spend elsewhere within the system. It all fits together. But if you’re asking for a hierarchy. The hierarchy needs to be: high quality, safe, patient care to start off with, to do that you need money, below that you need the whole implementation area.’

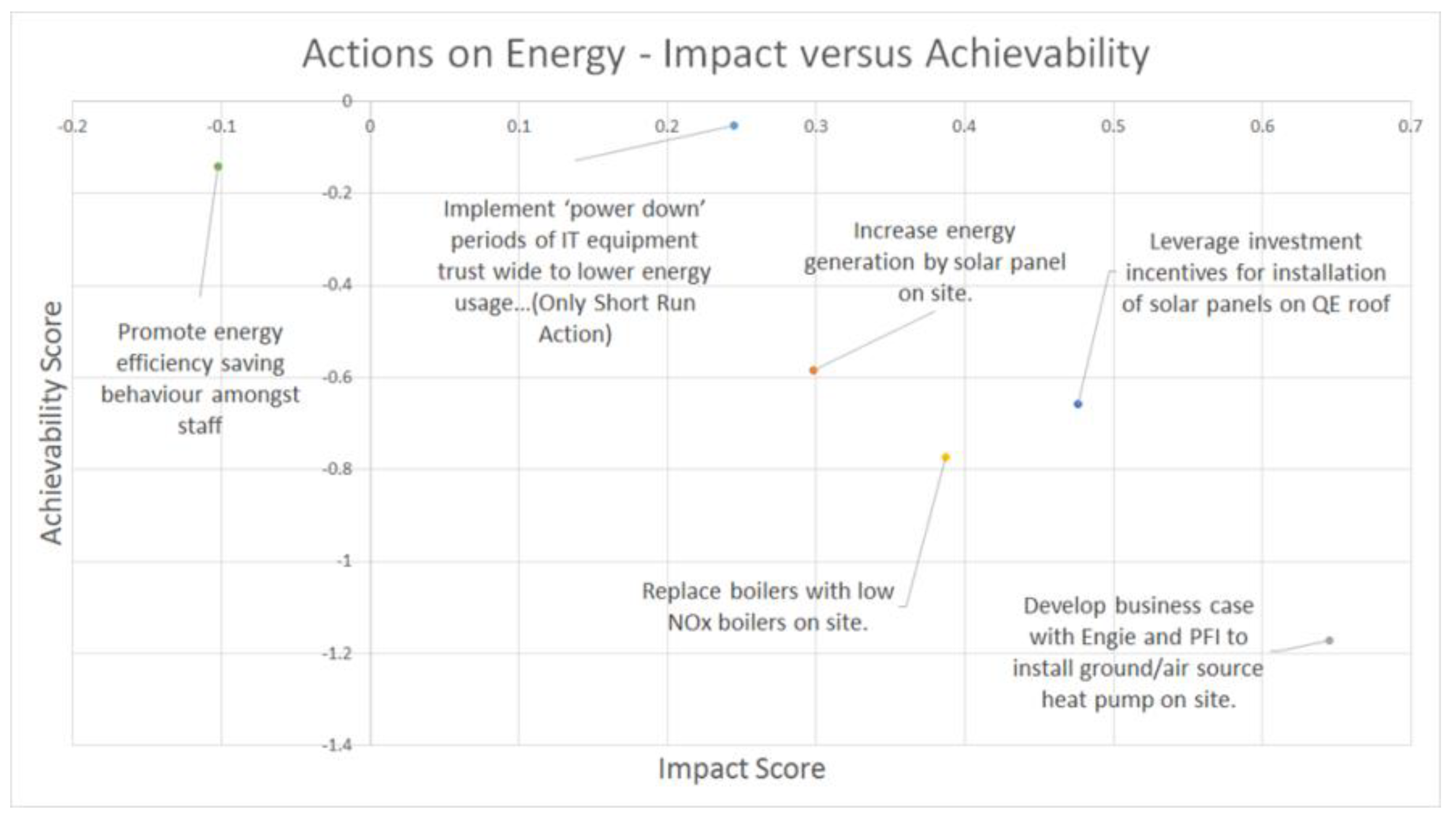

3.5. Energy

3.6. Communication and Training

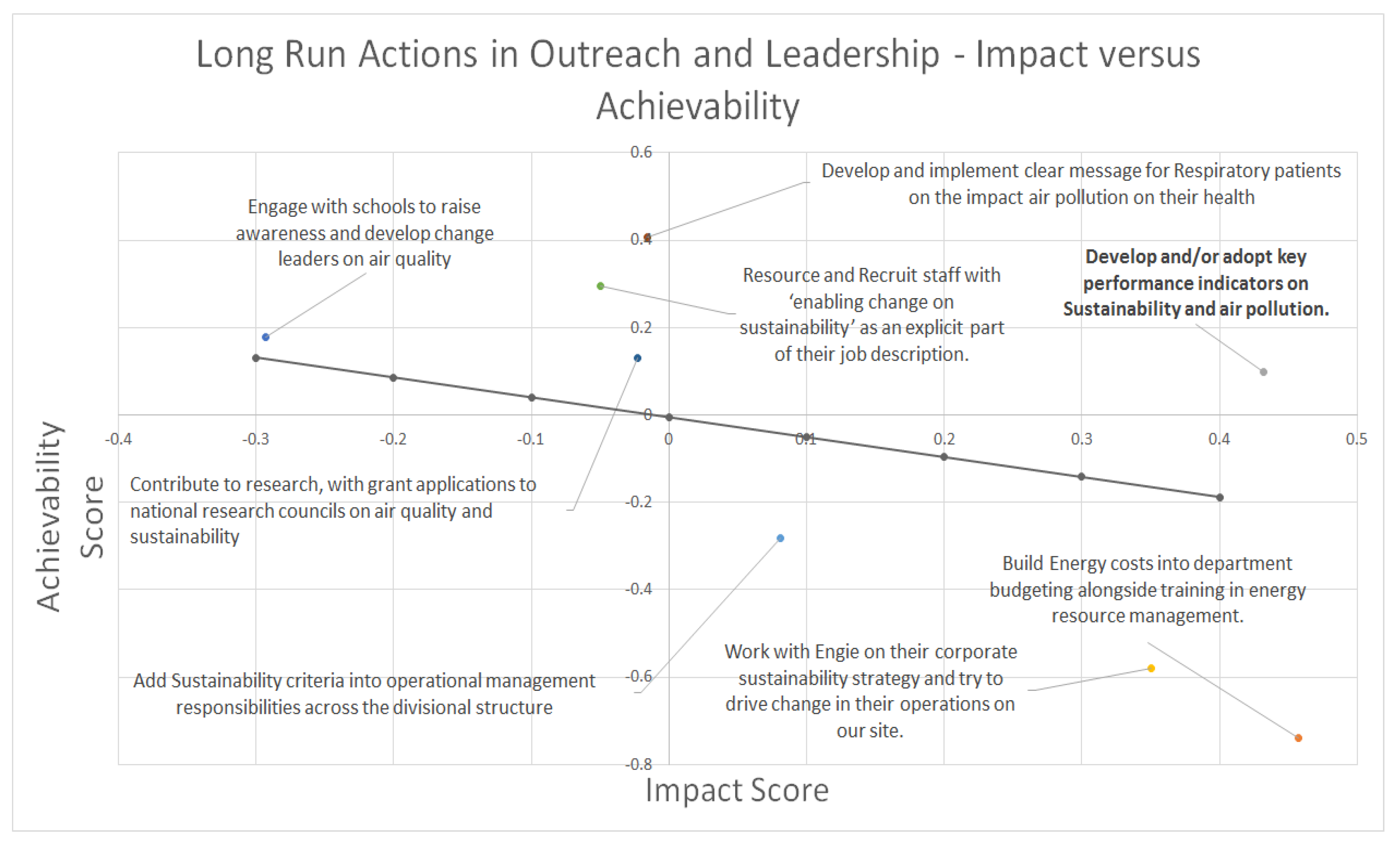

3.7. Outreach and Leadership

‘In every area of our clinical activity and our financial activity we are reporting against mandatory data requirements. If you can’t measure something in the NHS, you just can’t say anything about it.’

‘Whatever they are tested on, so however they show that they do their job well, they’ll do whatever they’re measured on, but they aren’t measured on sustainability… If they were measured on it they would do it, I think… when you set a measure, people will try to get the best number of that measure and if they can achieve that by not actually doing anything useful for sustainability they will. If they can achieve that by cheating, they’ll do it. But on the other hand they’ll still do some good things…’

3.8. Final Recommendations Table

4. Discussion

4.1. Remote Consultations

“Clinical consultations conducted through a video link tend to be associated with high satisfaction among patients and staff; no difference in disease progression; no substantial difference in service use; and lower transaction costs compared with traditional clinic based care.”

4.2. Transport Coordinators

4.3. Implement ‘Power Down’ Periods of IT Equipment Trust Wide to Lower Energy Usage, e.g., Automatic Shutdown on All Non-Essential Machines

4.4. Trust Builds Sustainability into Its Procurement Network with Points Given in Tender Processes for Use of Low Emission and Low Impact Supply Chains

4.5. Add Electric Cars to the Lease Scheme for Trust Fleet, Accompanied with the Phasing Out of Cars with Harmful Levels of Emissions; ‘/’ Trust Suppliers and Procurement Fleets Move to Electrical or Hydrogen Fuel to Replace Diesel Lorries and Vans’

4.6. Put Up More Signage around the Health Campus for Distances and Routes Connecting the Site to the City by Active Travel

4.7. Create Pricing Equity for Staff and Patients between Public Transport and Driving

4.8. Cargo Bikes for Hospital Logistics in the Long and Short Run

4.9. Embed Sustainable Transport within Patient Correspondence

4.10. Develop and/or Adopt Key Performance Indicators on Sustainability and Air Pollution

4.11. Research Limitations and Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Participant Information Sheet, Consent Form and Interview Sample Questions

| Principal Investigator: Dr Suzanne Bartington | |

| Name of Researcher: Owain Simpson | |

| Participant Identification Number: ______________ | |

| Participant Date of Birth: ______________________ | |

| Please initial each box | |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

Appendix B. Complete List of Actions Feature in Survey and Sorted into Policy Areas of Analysis

| Strategy and Policy on Travel |

| Introduce and enforce a strict no idling policy on site. |

| Step up engagement with the combined authority, UoB, BW&Cs to establish more safe cycle routes, particularly from Harborne and Quinton to the QE Hospital site, and also peripheral routes linking to the established major cycle routes. |

| Embedding sustainable transport within Patient Correspondence |

| Step up working with UoB, W&Cs, and combined authority on Bus and transport links to Hospital |

| Develop an emergency transport strategy for returning to work, using evidence based optimum levels of working from home and targeting increased proportion of staff using sustainable transport (incl. buses and trains) |

| Increase the rate of penalties for illegal parking on-site, specifically targeting delivery vehicles not using correct drop off locations and causing congestion. |

| Patient travel data collection through outpatient check-in system. |

| Resource and Recruit a Transport Coordinator for the trust. |

| Understand how much of our appointments and clinics are now run remotely and concentrate on improving that experience, ready with a plan for post-lockdown when patients wish to start returning to hospital. |

| With University of Birmingham, and other stakeholders in the University Station upgrade, construct business case for electrification of the cross city line. |

| Incentivising Lower Impact Travel |

| Offer staff who cycle to work a free breakfast. |

| Put up more signage around the health campus for distances and routes connecting the site to the city by active travel. |

| Taxis booked by the hospital are zero tailpipe emission vehicles. |

| Work with Engie to increase security on bike storage areas. |

| Negotiate for adaptive bikes to be made available on the cycle to work scheme. |

| Invest in secure cycle storage and more changing facilities across the QEUHB site. |

| Create pricing equity for staff and patients between public transport and driving. |

| Encourage the use of e-bikes to the site and publicise that staff are welcome to recharge batteries here. |

| Engage Canal and Rivers Trust on improving disabled access to the canal as part of University station project. |

| Implement a park and ride service from Longbridge. |

| Install EV charging in convenient places in car parking across trust site. |

| Procurement |

| Use more social prescribing for preventative healthcare at the staff well clinic. |

| Use cargo bikes for blood collection, transporting chemotherapy drugs and other logistics, this is already done at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford. |

| Trust builds sustainability into into its procurement network with points given in tender processes for use of low emission and low impact supply chains. |

| Trust suppliers and procurement fleet do not leave vehicles idling on site. |

| Trust suppliers and procurement fleet move to electrical or hydrogen fuel to replace diesel lorries and vans. |

| Trust suppliers and procurement fleet invest in cycle courier logistics to replace transport of supplies. |

| Prescribe dry rather than wet inhalers for patients for whom it can be just as effective. |

| Build business case with STP and its members specifically west midlands ambulance service to invest in digital transformation of system wide fleet coordination to join up logistics and commissioned patient carriage. For example patient pick-up vehicles leaving hospital site carry medications to pharmacies. |

| Add electric cars to the lease scheme for trust fleet, accompanied with the phasing out of cars with harmful levels of emissions. |

| Construction & Design |

| Work with construction firm on new hospital site to monitor air quality impact. |

| Assess air quality in wards in the new QE for patients that are already vulnerable, e.g., respiratory and cardiology. |

| Work with construction firm on new hospital to choose more sustainable building materials with less air quality impact, low VOCs etc. |

| Target the use of new technologies in the new hospital building for improved air quality control. e.g., AQ monitoring and live AQ control on air conditioning. |

| No idling policy for construction vehicles is established and enforced on site for the new hospital project, for both move-able and non-movable machinery. |

| Energy |

| Implement ‘power down’ periods of IT equipment trust wide to lower energy usage, automatic shutdown on all non-essential machines etc. |

| Increase the amount of energy generated through solar panels on site. |

| Work with Engie and PFI provider to build business case for ground/air source heat pump installation on site. |

| Invest in low NOx boilers in the heritage building and other trust owned buildings on site. |

| Leverage investment incentives for installation of photovoltaic cells on the roof of the New Queen Elizabeth Hospital |

| Strongly promote behaviour change in staff to start think about energy efficiency, e.g., wear jumper don’t just turn on the radiator, turn down radiators don’t open a window, turn off lights, turn off computers. |

| Direct Targeting of Local Air Quality |

| Develop our own dashboard of air quality measurement taken at the hospital for patients and staff to access live. |

| Install further and fixed AQ monitors around the site to build a better picture of AQ around the health campus. |

| Publicise local air quality information Tools to patients and staff. |

| Engage UoB and BW&Cs to take a combined approach to smoking across the health campus. |

| Facilitate Walking Meetings and meetings in outdoor spaces. |

| Implement a smoke-free hospital site. |

| Implement stronger and stricter rules on staff smoking on site to at least stop staff being seen smoking in uniform out with smoking shelters. |

| Improve rates of prescription of smoking patches for inpatients. |

| Invest in staff smoking cessation programme through staff well clinic. |

| Install hypoallergenic plants where it is safe and sensible to do so in the hospital. To improve air quality and environment in wards and other spaces. |

| Install protective screens and living walls in places where people are exposed to transport related air pollution on site (Atrium area, ED area, University station) |

| Trial stricter smoking enforcement in order to form an evidence base on direct and indirect consequences, gather more evidence for trust policy so that we know our policy is sound and valid. |

| Communication and Training |

| Organise a hard hitting seminar and awareness raising presentation for the trust’s board of directors on the seriousness of local air quality impacts on public health, and how localised change really makes a difference. |

| Add messaging around behaviour change to pay slips promoting active travel and sustainability |

| Collate Patient experiences of suffering as a result of air pollution. Publicise these accounts to raise awareness and promote behaviour change. |

| Create a sustainability in healthcare management module with the education department to disseminate knowledge and raise awareness. |

| Create medical training materials to feature on the grand rounds or generic teaching groups advising on current best practice around air quality |

| Develop staff guidelines for engaging with patients on issues of air quality and active travel. |

| Use posters and e-posters on electronic check-in to convey information on Health Impact of Air Pollution and how to protect yourself. |

| Adjust Trust policy on employees using social media in a professional context. Work to enable any staff wishing to use social media to raise awareness of health issues to do so, rather than attempting to present a single communication point. |

| Resource and Recruit an engagement lead who can engage in conversation with the public on a number of subjects, one area of which would be sustainability and air quality. |

| Outreach and Leadership |

| Add Sustainability criteria into operational management responsibilities across the divisional structure |

| Build Energy costs into department budgeting alongside training in energy resource management. |

| Create voluntary health and wellbeing ambassadors for promoting behaviour change in staff and patients. |

| Develop and/or adopt key performance indicators on Sustainability and air pollution. |

| Work with Engie on their corporate sustainability strategy and try to drive change in their operations on our site. |

| Engage with external organisations for Clean Air Day, use our platform to raise awareness, but keep funding for other projects instead. |

| Proactively Engage with local schools to raise awareness and develop change leaders who care about air quality impacts on health and actions we can take to improve. |

| Commit to resourcing activities for a Clean Air Day event and really make a big deal out of it. |

| Resource and Recruit staff with ‘enabling change on sustainability’ as an explicit part of their job description. |

| Seek out and commit to research collaboration with external and national organisations on air quality and sustainability in healthcare. |

| Work with Respiratory to develop a clear message to patients on the impact air pollution has on their health and then implement this across trust activities. |

References

- NHS England. NHS Long Term Plan. 2019. Available online: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- UK Clean Air Strategy. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/770715/clean-air-strategy-2019.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Travel in the NHS—Key Facts. Available online: https://www.bre.co.uk/page.jsp?id=2726 (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Pimpin, L.; Retat, L.; Fecht, D.; De Preux, L.; Sassi, F.; Gulliver, J.; Belloni, A.; Ferguson, B.; Corbould, E.; Jaccard, A.; et al. Estimating the costs of air pollution to the National Health Service and social care: An assessment and forecast up to 2035. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, D.; Moody, D. Multimorbidity—The Biggest Clinical Challenge Facing the NHS. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/blog/dawn-moody-david-bramley/ (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Slama, A.; Śliwczyński, A.; Woźnica, J.; Zdrolik, M.; Wiśnicki, B.; Kubajek, J.; Turżańska-Wieczorek, O.; Gozdowski, D.; Wierzba, W.; Franek, E. Impact of air pollution on hospital admissions with a focus on respiratory diseases: A time-series multi-city analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 16998–17009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Smith, S.; Dobney, A.; Thornes, J.; Smith, G.E.; Vardoulakis, S. Monitoring the effect of air pollution episodes on health care consultations and ambulance call-outs in England during March/April 2014: A retrospective observational analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 214, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajat, A.; Hsia, C.; O’Neill, M.S. Socioeconomic Disparities and Air Pollution Exposure: A Global Review. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, S.; Hebbern, C.; Cakmak, J.D.; Vanos, J. The modifying effect of socioeconomic status on the relationship between traffic, air pollution and respiratory health in elementary schoolchildren. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 177, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez, M.; López-Casasnovas, G. Assessing the Effects on Health Inequalities of Differential Exposure and Differential Susceptibility of Air Pollution and Environmental Noise in Barcelona, 2007–2014. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, D.D.; Dzhambov, A.M. Perceived access to recreational/green areas as an effect modifier of the relationship between health and neighbourhood noise/air quality: Results from the 3rd European Quality of Life Survey (EQLS, 2011–2012). Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 23, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, Q.; Kaufman, J.S.; Wang, J.; Copes, R.; Su, Y.; Benmarhnia, T. Effect of air quality alerts on human health: A regression discontinuity analysis in Toronto, Canada. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e2–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radisic, S.; Bruce Newbold, K. Factors influencing health care and service providers’ and their respective “at risk” populations’ adoption of the Air Quality Health Index (AQHI): A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- D’Antoni, D.; Auyeung, V.; Walton, H.; Fuller, G.W.; Grieve, A.; Weinman, J. The effect of evidence and theory-based health advice accompanying smartphone air quality alerts on adherence to preventative recommendations during poor air quality days: A randomised controlled trial. Environ. Int. 2019, 124, 216–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, J.; Williams, I.D. The impact of communicating information about air pollution events on public health. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 538, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karanasiou, A.; Viana, M.; Querol, X.; Moreno, T.; de Leeuw, F. Assessment of personal exposure to particulate air pollution during commuting in European cities-Recommendations and policy implications. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 490, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Nazelle, A.; Bode, O.; Orjuela, J.P. Comparison of air pollution exposures in active vs. passive travel modes in European cities: A quantitative review. Environ. Int. 2017, 99, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, E.; Forsberg, B. Health impacts of active commuters’ exposure to traffic-related air pollution in Stockholm, Sweden. J. Transp. Health 2019, 14, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Hirabayashi, S.; Doyle, M.; McGovern, M.; Pasher, J. Air pollution removal by urban forests in Canada and its effect on air quality and human health. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, C.; Harrison, R.; Querol, X. Review of the efficacy of low emission zones to improve urban air quality in European cities. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 111, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrsitz, M. The effect of low emission zones on air pollution and infant health. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2017, 83, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Robertson, C.; Ramsay, C.; Gillespie, C.; Napier, G. Estimating the health impact of air pollution in Scotland, and the resulting benefits of reducing concentrations in city centres. Spat. Spatio-Temporal Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudway, I.S.; Dundas, I.; Wood, H.E.; Marlin, N.; Jamaludin, J.B.; Bremner, S.A.; Cross, L.; Grieve, A.; Nanzer, A.; Barratt, B.M.; et al. Impact of London’s low emission zone on air quality and children’s respiratory health: A sequential annual cross-sectional study. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e28–e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, Y.; Jones, S.; Christmas, H.; Roderick, P.; Cooper, D.; McGready, K.; Gent, M. Collaborative health impact assessment and policy development to improve air quality in West Yorkshire-A case study and critical reflection. Climate 2017, 5, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunt, H.; Barnes, J.; Longhurst, J.W.S.; Scally, G.; Hayes, E. Enhancing Local Air Quality Management to maximise public health integration, collaboration and impact in Wales, UK: A Delphi study. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 80, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, E.; Green, J.; Chalabi, Z.; Wilkinson, P. Materialising links between air pollution and health: How societal impact was achieved in an interdisciplinary project. Health 2019, 23, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotcher, J.; Maibach, E.; Choi, W.T. Fossil fuels are harming our brains: Identifying key messages about the health effects of air pollution from fossil fuels. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University Hospitals Birmingham NHSFT (UHB). Greener Communities Healthier Lives—Sustainability Strategy. Available online: http://www.tya.uhb.nhs.uk/Downloads/pdf/sustainability-strategy.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Noy, C. Sampling Knowledge: The Hermeneutics of Snowball Sampling in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2008, 11, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejonckheere, M.; Vaughn, L.M. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigour. Fam. Med. Community Health 2019, 7, e000057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cathain, A.; Murphy, E.; Nicholl, J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ 2010, 341, c4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Malderen, L.; Jourquin, B.; Pecheux, C.; Thomas, I.; Van De Vijver, E.; Vanoutrive, T.; Verhetsel, A.; Witlox, F. Exploring the profession of mobility manager in Belgium and their impact on commuting. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2013, 55, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, M.; Thornes, J.E.; Banerjee, D.; Mitsakou, C.; Quaiyoom, A.; Delgado-Saborit, J.M.; Phalkey, R. Intervention of an Upgraded Ventilation System and Effects of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Air Quality at Birmingham New Street Railway Station. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornes, J.E.; Hickman, A.; Baker, C.; Cai, X.; Saborit, J.M.D. Air quality in enclosed railway stations. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Transp. 2017, 170, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, A.; Tremper, A.H.; Lin, C.; Priestman, M.; Marsh, D.; Woods, M.; Heal, M.R.; Green, D.C. Air quality in enclosed railway stations: Quantifying the impact of diesel trains through deployment of multi-site measurement and random forest modelling. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.; Karlsen, R.; Yu, W. Green transportation choices with IoT and smart nudging. In Handbook of Smart Cities: Software Services and Cyber Infrastructure; Maheswaran, M., Badidi, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A.; Brand, C. Assessing the potential for carbon emissions savings from replacing short car trips with walking and cycling using a mixed GPS-travel diary approach. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 123, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, G.; Clifton, K.J. Influence of individual perceptions and bicycle infrastructure on decision to bike. Transp. Res. Rec. 2009, 2140, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nazelle, A.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Antó, J.M.; Brauer, M.; Briggs, D.; Braun-Fahrlander, C.; Cavill, N.; Cooper, A.R.; Desqueyroux, H.; Fruin, S.; et al. Improving health through policies that promote active travel: A review of evidence to support integrated health impact assessment. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondschein, A.; Blumenberg, E.; Taylor, B. Accessibility and cognition: The effect of transport mode on spatial knowledge. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 845–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Transport, UK Government. Transport Use during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. 2020. Available online: www.gov.uk (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Air Quality Expert Group, DEFRA. Non-Exhaust Emissions from Road Traffic. 2019. Available online: https://uk-air.defra.gov.uk/assets/documents/reports/cat09/1907101151_20190709_Non_Exhaust_Emissions_typeset_Final.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Buchanan, R. Wicked Problems in Design Thinking. Des. Issues 1992, 8, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Plsek, P.E.; Greenhalgh, T. The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ 2001, 323, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plsek, P.E.; Wilson, T. Complexity, leadership, and management in healthcare Organisations. BMJ 2001, 323, 746–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.R.; Roe, M.T.; Peterson, E.D.; Chen, A.Y.; Gibler, W.B.; Armstrong, P.W. Better outcomes for patients treated at hospitals that participate in clinical trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, L.; Fisher, S.J.; Dagnan, D. Patients admitted to more research-active hospitals have more confidence in staff and are better informed about their condition and medication: Results from a retrospective cross-sectional study. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2020, 26, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrina, E.; Vilsi, A.L. Key Performance Indicators for Sustainable Manufacturing Evaluation in Cement Industry. Procedia CIRP 2015, 26, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, M.; Pinna, C.; Aliakbarian, B.; Tonelli, F.; Terzi, S. Soft Drink Supply Chain Sustainability: A Case Based Approach to Identify and Explain Best Practices and Key Performance Indicators. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggan, J.C.; Shoup, J.P.; Whited, J.D.; Van Voorhees, E.; Gordon, A.M.; Rushton, S.; Lewinski, A.A.; Tabriz, A.A.; Adam, S.; Fulton, J.; et al. Effectiveness of Acute Care Remote Triage Systems: A Systematic Review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 2136–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corden, E.; Rogers, A.K.; Woo, W.A.; Simmonds, R.; Mitchell, C.D. A targeted response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Analysing effectiveness of remote consultations for triage and management of routine dermatology referrals. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 45, 1047–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohenschurz-Schmidt, D.; Scott, W.; Park, C.; Christopoulos, G.; Vogel, S.; Draper-Rodi, J. Remote management of musculoskeletal pain: A pragmatic approach to the implementation of video and phone consultations in musculoskeletal practice. PAIN Rep. 2020, 5, e878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macken, J.H.; Fortune, F.; Buchanan, J.A.G. Remote telephone clinics in Oral Medicine—Reflections on the place of virtual clinics in a specialty that relies so heavily on visual assessment. A note of caution. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 59, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskins, Z.; Crawford-Manning, F.; Bullock, L.; Jinks, C. Identifying and managing osteoporosis before and after COVID-19: Rise of the remote consultation? Osteoporos. Int. 2020, 31, 1629–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Burt, J.; Chowdhury, T.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Martin, G.; Van Der Scheer, J.W.; Hurst, J.R. Specialty COPD care during COVID-19: Patient and clinician perspectives on remote delivery. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2021, 8, e000817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Wherton, J.; Shaw, S.; Morrison, C. Video consultations for COVID-19. BMJ 2020, 368, m998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, C.; Gifford, R.; Brown, E. The Influence of Descriptive Social Norm Information on Sustainable Transportation Behavior: A Field Experiment. Environ. Behav. 2020, 47, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartle, C.; Avineri, E. Final Report Prepared for ‘Ideas in Transit’ WP34 (GeoVation): User Participation in the Design of Innovative Information Services to Influence Travel Behaviour: The ‘myPTP’ Case Study. Cent Transp. Soc. 2012, 1–29. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/2811497/Final_Report_prepared_for_Ideas_in_Transit_WP34_GeoVation (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Copsey, S.L. The Development and Implementation Processes of a Travel Plan Within the Context of a Large Organisation: Using an Embedded Case Study Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hertfordshire, Hertfordshire, UK, 2013. Available online: https://uhra.herts.ac.uk/handle/2299/10331 (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Berl, A.; Race, N.; Ishmael, J.; De Meer, H. Network virtualization in energy-efficient office environments. Comput. Netw. 2010, 54, 2856–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, A.C.; Cripps, A.; Buswell, R.A.; Wright, J.; Bouchlaghem, D. Estimating the energy consumption and power demand of small power equipment in office buildings. Energy Build. 2014, 75, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulville, M.; Jones, K.; Huebner, G. The potential for energy reduction in UK commercial offices through effective management and behaviour change. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2014, 10, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulville, M.; Jones, K.; Huebner, G.; Powell-greig, J. Energy-saving occupant behaviours in offices: Change strategies. Archit. Build. Res. Inf. 2017, 45, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maula, H.; Hongisto, V.; Naatula, V.; Haapakangas, A.; Koskela, H. The effect of low ventilation rate with elevated bioeffluent concentration on work performance, perceived indoor air quality, and health symptoms. Indoor Air 2017, 27, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destaillats, H.; Maddalena, R.L.; Singer, B.C.; Hodgson, A.T.; Mckone, T.E. Indoor pollutants emitted by office equipment: A review of reported data and information needs. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 1371–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindfors, A.; Ammenberg, J. Using national environmental objectives in green public procurement: Method development and application on transport procurement in Sweden. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, J.D.; Raibley, L.A.; Eckelman, M.J. Life Cycle Assessment and Costing Methods for Device Procurement: Comparing Reusable and Single-Use Disposable Laryngoscopes. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 127, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikusinska, M. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Surgical Scrub Suits. Ph.D. Thesis, KTH—Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2012. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:574013/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Unger, S.; Landis, A. Assessing the environmental, human health, and economic impacts of reprocessed medical devices in a Phoenix hospital’s supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1995–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Transport (DfT). Tendering Road Passenger Transport Contracts Best Practice Guidance Department for Transport. 2013. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/254392/tendering-road-passenger-transport-contracts.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Smallbone, A.; Jia, B.; Atkins, P.; Paul, A. Energy Conversion and Management: X The impact of disruptive powertrain technologies on energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions from heavy-duty vehicles. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2020, 6, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandarajah, G.; McDowall, W.; Ekins, P. Decarbonising road transport with hydrogen and electricity: Long term global technology learning scenarios. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2013, 38, 3419–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, E.; Browne, M. Technical and operational obstacles to the adoption of electric vans in France and the UK: An operator perspective. Transp. Policy 2018, 63, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environmental Agency (EEA)—Electric Vehicles from Life Cycle and Circular Economy Perspectives—TERM. 2018. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/electric-vehicles-from-life-cycle (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Zuniga, K.D. From barrier elimination to barrier negotiation: A qualitative study of parents’ attitudes about active travel for elementary school trips. Transp. Policy 2012, 20, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, A.; Buehler, R. Commuter mode choice and free car parking, public transportation benefits, showers/lockers, and bike parking at work: Evidence from the Washington DC region. J. Public Transp. 2014, 17, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, L.; Friman, M.; Gärling, T.; Hartig, T. Quality attributes of public transport that attract car users: A research review. Transp. Policy 2013, 25, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. Coronavirus: Free Buses and Trams for West Midlands NHS Staff. 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-birmingham-52153700#:~:text=Coronavirus%3A (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Public Services (Social Value) Act. 2012. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/3/enacted (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Catano, V.M.; Hines, H.M. The influence of corporate social responsibility, psychologically healthy workplaces, and individual values in attracting millennial job applicants. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2018, 48, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetunji, O.J.; Ogbonna, I.G. Corporate Social Responsibility as a Recruitment Strategy by Organisations. Int. Rev. Manag. Bus. Res. 2013, 2, 313–319. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, J.; Kihm, A.; Lenz, B. Research in Transportation Business & Management A new vehicle for urban freight? An ex-ante evaluation of electric cargo bikes in courier services. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 11, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schliwa, G.; Armitage, R.; Aziz, S.; Evans, J.; Rhoades, J. Sustainable city logistics—Making cargo cycles viable for urban freight transport. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2015, 15, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, S.; Sloman, L. Potential for E-Cargo Bikes to Reduce Congestion and Pollution from Vans in Cities. Available online: https://www.bicycleassociation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Potential-for-e-cargo-bikes-to-reduce-congestion-and-pollution-from-vans-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Gössling, S. ICT and Transport Behavior: A Conceptual Review. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2018, 12, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsuppakorn, P.; Karimi, H.A. Personalised routing for wheelchair navigation. J. Locat. Based Serv. 2009, 3, 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socharoentum, M.; Karimi, H.A. A comparative analysis of routes generated by Web Mapping APIs. Cartograph. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2015, 42, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.; Pelta, D.A.; Verdegay, J.L. PRoA: An intelligent multi-criteria Personalized Route Assistant. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2018, 72, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Varriale, L.; Alvino, F. Key performance indicators for developing environmentally sustainable and energy efficient ports: Evidence from Italy. Energy Policy 2018, 122, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.V.; Garcia, A.; Rodriguez, L. Sustainable Development and Corporate Performance: A Study Based on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I.; Chirico, A. The Role of Sustainability Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) in Implementing Sustainable Strategies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, N.G. Triangulation and Mixed Methods Designs: Data Integration With New Research Technologies. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2012, 6, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant’s Professional Field | Area (s) of Expertise |

|---|---|

| Strategy and Analysis | Designing sustainability strategy at UHB; the operational specifics of the QEHB |

| Respiratory Medicine | Air quality and its impacts on healthcare and Public Health |

| Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement | Working in engagement and communications to do with air quality and sustainability |

| Medical Physics | Leading change at UHB; the operational specifics of the QEHB |

| Public Health and Environmental Epidemiology | Understanding air quality and its impacts on healthcare and Public Health; working in engagement and communications to do with air quality and sustainability |

| Quality Development | Leading change at UHB; designing sustainability strategy at UHB; the operational specifics of the QEHB |

| Innovation and Trust Leadership | Leading change at UHB; designing sustainability strategy at UHB; the operational specifics of the QEHB |

| Estates | Leading change at UHB; designing sustainability strategy at UHB; the operational specifics of the QEHB |

| Operations | leading change at UHB; designing sustainability strategy at UHB; the operational specifics of the QEHB; working in engagement and communications to do with air quality and sustainability |

| Estates | Working in engagement and communications to do with air quality and sustainability |

| Finance | Leading change at UHB, designing sustainability strategy at UHB, the operational specifics of the QEHB, working in engagement and communications to do with air quality and sustainability |

| Actions | Survey Score | Interview Consensus | Barriers /Trade-Offs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Impact | Achievability | |||

| 1 | Quantify Hospital Activity run remotely, then undertake improvement of quality and efficiency of these services for post-lockdown to prevent return to business as usual | 1.09 | 0.38 | All positive | IT Video Consultation Capacity |

| 2 | Create the Transport Coordinator Role | 0.64 | 0.50 | All positive | Cost |

| 3 | Develop an emergency transport plan for returning to work. Establish real optimum levels of home working and target sustainable transport use to establish new habits | 0.57 | −0.46 | All positive | Staff Health Impacts/ productivity concerns |

| 4 | Implement ‘power down’ periods of IT equipment trust wide overnight | 0.24 | −0.05 | Majority Positive | None |

| 5 | Build sustainability into procurement processes rewarding low emission and low impact supply chains | 0.94 | −0.22 | All positive | Cost/ Complexity/ national policies on procurement |

| 6 | Convert fleet to electrical or hydrogen fuel to replace diesel lorries and vans | 0.81 | −0.38 | All Positive | Cost |

| 7 | Put up more directions and information around the health campus for active travel | −0.57 | 1.11 | All positive | None |

| 8 | Gradually install EV charging in convenient places in car parking across the trust site | 0.47 | −0.15 | Majority Positive | Car parking capacity/current low demand |

| 9 | Create pricing equity between public transport and driving for staff and patients | 0.08 | −0.56 | Majority Positive | Concern over staff dissatisfaction at cost of parking |

| 10 | Review logistics fleet to assess capacity of cycle courier logistics | −0.29 | 0.04 | No | Lack of Knowledge about capability/capacity |

| 11 | Collect Patient and visitor travel data through check-in systems | −0.13 | 0.50 | Majority Positive | Opportunity cost of not collecting other data for other purposes |

| 12 | Embed sustainable transport within Patient Correspondence | 0.22 | 1.14 | Majority Positive | None |

| 13 | Create and promote a ‘sustainability in healthcare management’ module with the education department | 0.16 | 0.37 | All positive | None |

| 14 | Adopt evidenced KPIs measuring performance against sustainability and air quality criteria | 0.43 | 0.10 | Majority positive | More pressure on staff to meet more targets/cost |

| 15 | Build more and better secure cycle storage. | 0.16 | 0.33 | Majority positive | None |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simpson, O.; Elliott, M.; Muller, C.; Jones, T.; Hentsch, P.; Rooney, D.; Cowell, N.; Bloss, W.J.; Bartington, S.E. Evaluating Actions to Improve Air Quality at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811128

Simpson O, Elliott M, Muller C, Jones T, Hentsch P, Rooney D, Cowell N, Bloss WJ, Bartington SE. Evaluating Actions to Improve Air Quality at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811128

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimpson, Owain, Mark Elliott, Catherine Muller, Tim Jones, Phillippa Hentsch, Daniel Rooney, Nicole Cowell, William J. Bloss, and Suzanne E. Bartington. 2022. "Evaluating Actions to Improve Air Quality at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811128

APA StyleSimpson, O., Elliott, M., Muller, C., Jones, T., Hentsch, P., Rooney, D., Cowell, N., Bloss, W. J., & Bartington, S. E. (2022). Evaluating Actions to Improve Air Quality at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust. Sustainability, 14(18), 11128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811128