Food Systems in Informal Urban Settlements—Exploring Differences in Livelihood Welfare Factors across Kibera, Nairobi

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- Who are the people living in Kibera, and how are tribes distributed across the villages?

- (2)

- How do selected welfare factors vary across Kibera, such as income, land and source of electricity?

- (3)

- How do trust levels differ for various actors across the villages of Kibera?

- (4)

- To which extent do levels of food insecurity vary across the Kibera villages?

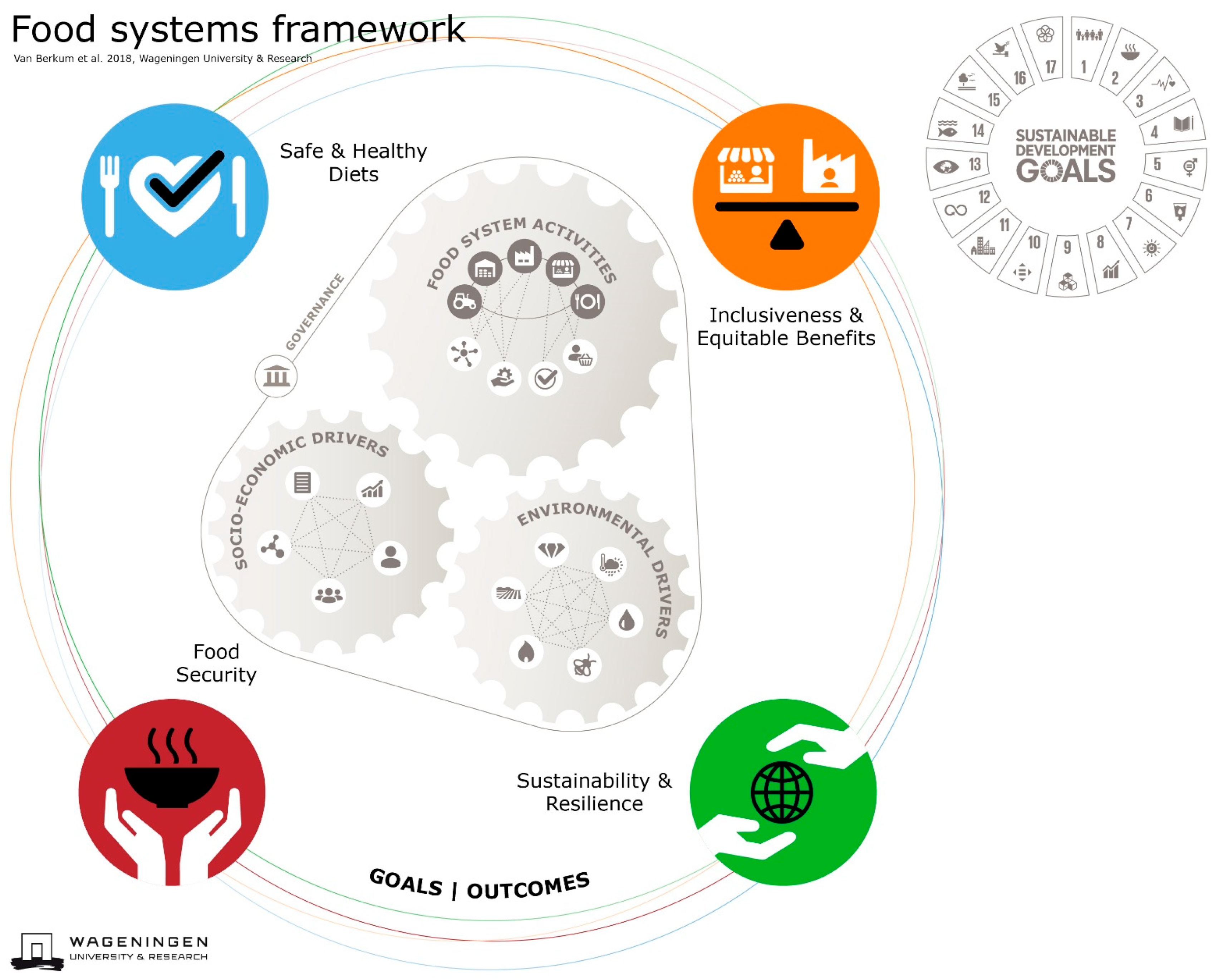

2. A Food System Approach

3. Methodological Approach

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

- Did you worry that your household would not have enough food? How often?

- Were you or any household member not able to eat the kinds of foods you preferred because of a lack of resources? How often?

- Did you or any household member have to eat a limited variety of foods due to a lack of resources? How often?

- Did you or any household member have to eat some foods that you really did not want to eat because of a lack of resources to obtain other types of food? How often?

- Did you or any household member have to eat smaller meals than you felt you needed because there was not enough food? How often?

- Did you or any household member have to eat fewer meals in a day because there was not enough food? How often?

- Was there ever no food to eat of any kind in your household because of lack of resources to get food? How often?

- Did you or any household member go to sleep at night hungry because there was not enough food? How often?

- Did you or any household member go a whole day and night without eating anything because there was not enough food? How often?

4. Results

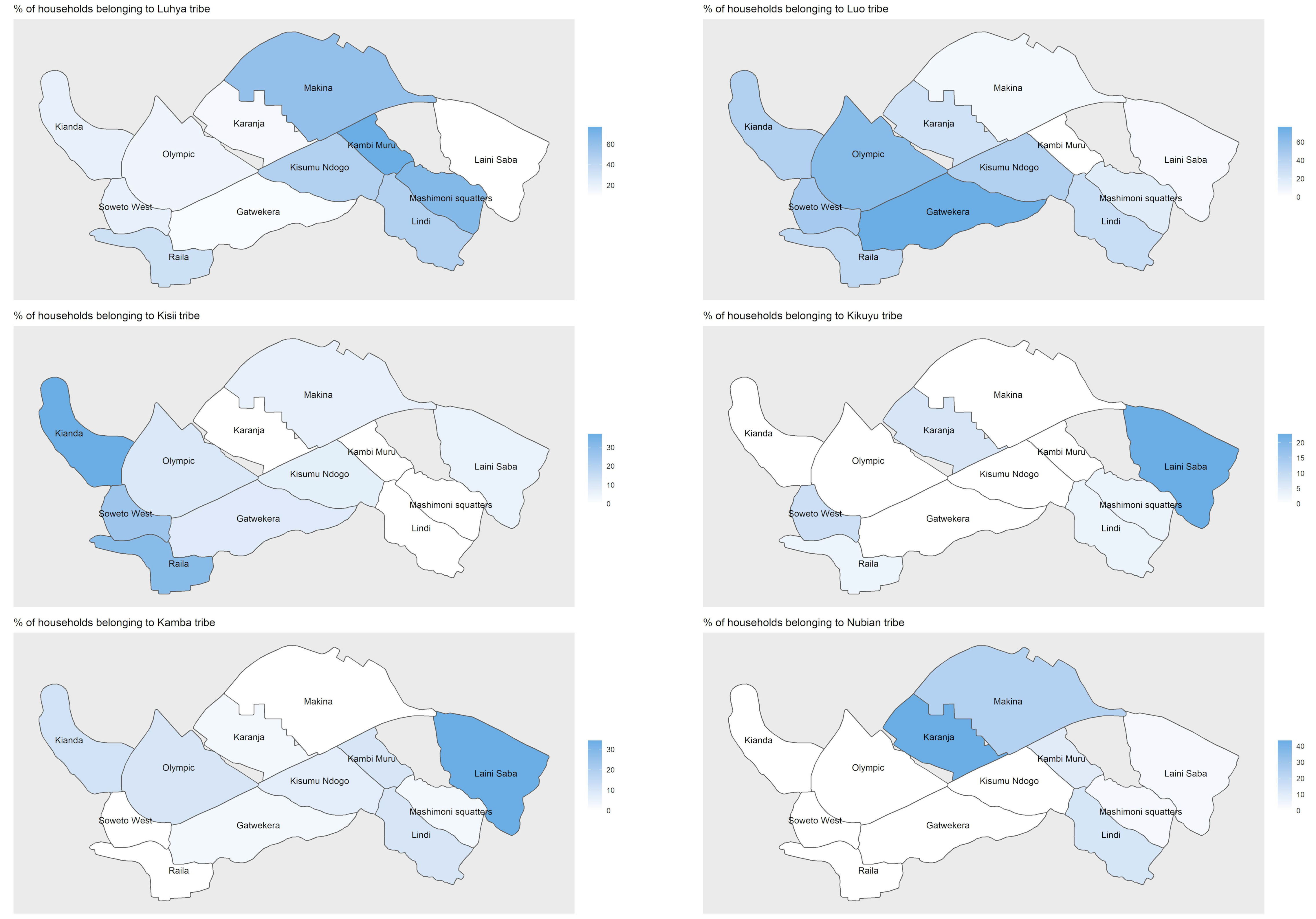

4.1. Who Are the People Living in Kibera, and How Are Tribes Distributed across the Villages?

4.2. How Do Selected Welfare Factors, such as Income, Land and Source of Electricity Vary across Kibera?

4.3. How Do Trust Levels Differ for Various Actors across the Villages of Kibera?

4.4. To which Extent Do Levels of Food Insecurity Vary across the Kibera Villages?

5. Discussing Differences in Livelihood Welfare Factors across Kibera and Food System Outcomes

6. Concluding Remarks

- The differences across villages in Kibera are large and can be linked with the dominant tribe in the specific village. For instance, two villages (Laini Saba and Karanja) are dominated by tribes with less connectivity to rural areas in Western Kenya, with Laini Saba having a majority of Kamba and Kikuyu tribes who relate to the region of Mount Kenya and Eastern Kenya, and Karanja having most of the Nubians, who are not originally from Kenya, but were World War I veterans given temporary residence permits by the British colonial government between 1912 and 1934 [7,44]. The Luos and Luhyas are tribes from Western Kenya who in varying degrees dominate the other villages. Notably, also within these villages a series of welfare factors differ significantly, for instance, connection with Western Kenya, owning land in rural areas, access to steady electricity and trust in county government;

- The selected income factors differ across the villages, with Laini Saba having the lowest, and Olympic having the highest average income levels. The variability in owning land in rural areas is high, ranging from a total of 69% owning land in Kianda, to only 33% owning land in Laini Saba. In addition, access to electricity varied highly across the villages, for which Makina ranged the highest, with 77% having access, to only 17% having access in Laini Saba;

- The trust levels, ranging from 1 to 5 on a scale where 1 refers to lowest level of trust, and 5 the highest, was shown to be highest for ‘people from the village’, followed by ‘community leader in Kibera’. However, looking at the variability across the villages, the trust in the county government was significantly different from the average for a total of six villages. Only in Laini Saba was the trust in strangers higher than average;

- Food insecurity measured on a HFIAS scale showed variability, with Laini Saba ranging the highest and Karanja, Makina and Lindi lowest, confirming higher food security in these three villages than average.

- Outcomes of the food system were investigated in this study along with food security, inclusiveness and equitable benefits and sustainability and resiliency, but did not directly take safe and healthy diets into account. Although this was covered more substantially in the paper by Ayuya et al. [20] on fish nutrition in Kibera, it is recommended to further investigate safe and healthy diets, including the consumption of indigenous vegetables in informal settlements;

- To achieve higher welfare with no increase in climate emissions it is recommended to investigate bottlenecks such as access to finance and access to affordable green energy-based innovations and their differences across villages, as well as to analyze the climate and welfare impacts of such innovations;

- To achieve real impact, the informal economy must be understood and recognized as an equal partner. It is advised to investigate the potential to invest and set up business opportunities among the lowest income groups, in communities with high social capital [21].

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Statistical Tests of Discrepancies between Livelihood Factors in a Village and the Average in Kibera

| Kibera (total) | Gatwekera | Kambi Muru | Karanja | Kianda | Kisumu Ndogo | Laini Saba | Lindi | Makina | Mashimoni Squatters | Olympic | Raila | Soweto West | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 3: Households (hh) origin (tribe) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| % of hh belonging to the tribe Luhya | 34% | 12% | ** | 77% | *** | 13% | * | 20% | + | 46% | 9% | *** | 47% | 60% | ** | 67% | *** | 17% | * | 33% | 20% | + | |||

| % of hh belonging to the tribe Luo | 33% | 76% | *** | 0% | *** | 27% | 43% | 43% | 6% | *** | 30% | 7% | ** | 17% | * | 63% | *** | 36% | 49% | * | |||||

| % of hh belonging to the tribe Kikuyu | 4% | 0% | 0% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 23% | *** | 3% | 0% | 3% | 0% | 3% | 9% | |||||||||||

| % of hh belonging to the tribe Kisii | 12% | 9% | 0% | * | 0% | * | 37% | *** | 7% | 6% | 0% | * | 7% | 0% | * | 10% | 30% | *** | 26% | ** | |||||

| % of hh belonging to the tribe Nubian | 8% | 0% | + | 10% | 43% | *** | 0% | + | 0% | 3% | 13% | 23% | *** | 3% | 0% | 0% | + | 0% | + | ||||||

| % of hh belonging to the tribe Kamba | 8% | 3% | 10% | 3% | 11% | 7% | 34% | *** | 10% | 0% | + | 3% | 10% | 0% | + | 0% | + | ||||||||

| Figure 4: Household (hh) practices | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mean years hh lived in Kibera | 20.7 | 21.47 | 21.2 | 31.7 | *** | 15.4 | * | 19.4 | 22.4 | 21.1 | 21.4 | 24.5 | 17.9 | 12.8 | ** | 19.9 | |||||||||

| % of neighbors sharing the same cultural practices | 45% | 67% | *** | 42% | 40% | 44% | 43% | 38% | + | 51% | 42% | 38% | + | 48% | 49% | 42% | |||||||||

| Mean number of times hh visit their rural area per year | 1.60 | 1.44 | 1.33 | 2.63 | ** | 1.69 | 1.64 | 1.60 | 1.77 | 0.93 | + | 1.47 | 1.57 | 1.42 | 1.66 | ||||||||||

| % of hh head who connect with Western Kenya | 75% | 97% | ** | 77% | 40% | *** | 89% | * | 89% | + | 20% | *** | 77% | 63% | 87% | 83% | 88% | + | 89% | * | |||||

| Figure 5: Household (hh) characteristics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Household size | 4.63 | 4.50 | 4.20 | 4.90 | 4.50 | 4.60 | 4.00 | + | 3.80 | * | 4.40 | 5.80 | ** | 5.20 | + | 5.10 | 4.70 | ||||||||

| % of hh heads who have secondary education (from 4–6 years) or higher | 48% | 47% | 57% | 60% | 49% | 57% | 29% | * | 60% | 47% | 27% | * | 77% | ** | 42% | 37% | |||||||||

| % of hh heads who are married | 67% | 85% | * | 57% | 63% | 77% | 68% | 57% | 67% | 70% | 60% | 67% | 73% | 63% | |||||||||||

| % of hh heads who are female | 3% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 6% | 4% | 0% | 3% | 7% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 0% | ||||||||||||

| Figure 6: Household (hh) welfare | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mean monthly income (KES) | 13,094 | 14,726 | 12,555 | 14,827 | 12,267 | 12,411 | 9840 | * | 14,703 | 15,578 | 10,843 | 17,053 | * | 11,506 | 11,684 | ||||||||||

| % of hh for whom their income is enough | 36% | 47% | 27% | 37% | 34% | 25% | 34% | 50% | 47% | 27% | 33% | 42% | 31% | ||||||||||||

| % of hh owning land in rural areas | 51% | 65% | + | 67% | + | 33% | * | 69% | * | 54% | 31% | * | 33% | * | 37% | 63% | 50% | 52% | 51% | ||||||

| Mean land size in rural areas (hectares) | 1.41 | 1.97 | 1.74 | 1.85 | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.31 | 3.33 | ** | 0.83 | 1.27 | 1.43 | 1.06 | 0.78 | |||||||||||

| Figure 7: Household (hh) spending and loans | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mean % of income sent to rural areas | 6% | 9% | * | 4% | 6% | 7% | 6% | 3% | * | 6% | 4% | 6% | 7% | 5% | 4% | ||||||||||

| % of hh receiving food gifts | 56% | 79% | ** | 63% | 20% | *** | 63% | 39% | + | 46% | 57% | 40% | + | 57% | 77% | * | 61% | 66% | |||||||

| % of hh having savings | 13% | 18% | 13% | 20% | 15% | 14% | 9% | 14% | 13% | 3% | 10% | 6% | 20% | ||||||||||||

| % of hh having loans | 35% | 32% | 37% | 28% | 24% | 46% | 29% | 31% | 30% | 40% | 53% | * | 33% | 37% | |||||||||||

| Figure 8: Household (hh) use of energy source | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| % of hh having access to steady electricity | 48% | 44% | 63% | + | 67% | * | 46% | 61% | 17% | *** | 37% | 77% | ** | 27% | * | 57% | 36% | 54% | |||||||

| % of hh using of charcoal as energy source | 19% | 24% | 17% | 17% | 17% | 21% | 3% | * | 20% | 13% | 23% | 33% | * | 12% | 26% | ||||||||||

| % of hh using paraffin as energy source | 40% | 32% | 47% | 37% | 34% | 39% | 54% | + | 37% | 37% | 47% | 23% | + | 55% | + | 34% | |||||||||

| % of hh using LPG as energy source | 36% | 41% | 37% | 47% | 49% | 36% | 31% | 37% | 47% | 17% | * | 33% | 27% | 34% | |||||||||||

| Figure 9: Trust relations on a scale from 1 (low) to 5 (high) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trust in strangers (1–5) | 2.06 | 1.97 | 2.13 | 2.17 | 2.11 | 1.75 | 2.54 | ** | 1.79 | 1.97 | 1.97 | 1.87 | 2.09 | 2.26 | |||||||||||

| Trust in people from the village (1–5) | 3.01 | 2.88 | 3.20 | 3.30 | 2.77 | 3.04 | 2.94 | 2.83 | 3.13 | 3.4 | + | 2.73 | 3.15 | 2.77 | |||||||||||

| Trust in national government (1–5) | 2.42 | 2.64 | 2.130 | 2.57 | 2.66 | 2.79 | 2.09 | 2.17 | 2.72 | 2.97 | * | 2.07 | 2.06 | + | 2.24 | ||||||||||

| Trust in county government (1–5) | 2.27 | 2.59 | + | 1.90 | + | 2.62 | + | 2.06 | 2.39 | 2.23 | 2.27 | 2.47 | 2.62 | + | 1.85 | + | 1.91 | + | 2.30 | ||||||

| Trust in local politicians (1–5) | 2.01 | 2.32 | 1.70 | 2.23 | 1.86 | 2.14 | 1.97 | 1.83 | 2.27 | 2.23 | 1.89 | 1.82 | 1.91 | ||||||||||||

| Trust in community leader (1–5) | 2.46 | 2.73 | 2.37 | 2.53 | 2.15 | 2.44 | 2.06 | + | 2.63 | 2.93 | * | 2.80 | 2.43 | 2.52 | 2.09 | + | |||||||||

| Figure 10: Food insecurity | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hh Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) scores | 7.97 | 8.47 | 8.63 | 6.20 | * | 7.89 | 7.36 | 9.40 | + | 6.13 | * | 6.37 | + | 9.23 | 8.50 | 9.27 | 7.71 | ||||||||

References

- Archambault, C.S.; De Laat, J.; Zulu, E.M. Urban services and child migration to the slums of Nairobi. World Dev. 2012, 40, 1854–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallaher, C.M.; Kerr, J.M.; Njenga, M.; Karanja, N.K.; WinklerPrins, A.M.G.A. Urban agriculture, social capital, and food security in the Kibera slums of Nairobi, Kenya. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 30, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olack, B.; Feikin, D.R.; Cosmas, L.O.; Odero, K.O.; Okoth, G.O.; Montgomery, J.M.; Breiman, R.F. Mortality Trends Observed in Population-Based Surveillance of an Urban Slum Settlement, Kibera, Kenya, 2007–2010. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, L.I.; Chaudhuri, J.; Kagima, B. Kenya’s focus on urban vulnerability and resilience in the midst of urban transitions in Nairobi. Dev. South Afr. 2016, 33, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, B.; Odaba, E. Access to water in a Nairobi slum: Women’s work and institutional learning. Water Int. 2010, 35, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achungo, B.C. The Social Transformation of the people living in Kibera Slum in Nairobi County following the Kenya Slum upgrading programme. Master’s Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 11 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kibere, F.N. The Capability of Mobility in Kibera’ Slum’, Kenya: An Ethnographic Study of How Young People Use and Appropriate New Media and ICTS. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK, 6 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ngongo, C.J.; Mathingau, F.A.; Burke, H.; Brieger, W.; Frick, K.; Chapman, K.; Breiman, R. Community Par-ticipation to refine measures of socio-economic status in urban settings in Kenya. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2008, 28, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seal, D.; Bown, R.T.; Parker, A.H. Penetrometer tests on 109 pit latrines in Kibera, Nairobi, Kenya. Water SA 2018, 44, 1816–7950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KNBS. Kenya Population and Housing Census: Vol 1: Population by County and Sub-County; Kenya National Bureau of Statistics: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Gulyani, S.; Talukdar, D. Informal Rental Markets: The Low-Quality, High-Price Puzzle in Nairobi’s Slums. In Urban Land Markets; Lall, S.V., Freire, M., Yuen, B., Rajack, R., Helluin, J.J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 191–223. [Google Scholar]

- Marras, S. Mapping the Unmapped; University of Milano-Bicocca: Milano, Italia, 2012; p. 4. Available online: http://mapkiberaproject.yolasite.com/resources/Kibera_mapping_the_unmapped.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Lunch Bowl Network. 1.5 mill Luncbowl. Facts and Information about Kibera. 2015. Available online: http://www.lunchbowl.org/the-kibera.html (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- De Bercegol, R.; Monstadt, J. The Kenya slum electrification program. Local politics of electricity networks in Kibera. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 41, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongosi, A.N.; Gericke, G.; Mbuthia, E.; Oelofse, A. Food variety, dietary diversity and perceived hunger among lactating women (0-6 months postpartum) in a low socio-economic area in Nairobi, Kenya. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2014, 14, 8663–8675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgroppes, A.; Taupin, S. Kibera: The Biggest Slum in Africa? East Afr. Rev. 2011, 44, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Berkum, S.; Dengerink, J.; Ruben, R. The Food Systems Approach: Sustainable Solutions for a Sufficient Supply of Healthy Food; Memorandum 2018-064; Wageningen Economic Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2018; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Van Berkum, S.; Broeze, J.; Herens, M.; de Rooij, B.; Soma, K.; Roosendaal, L. Urbanisation, Migration and Food System Transformations: Concepts and Methodologies for a Better Understanding of the Dynamics of Urban Food Systems and Migration Settlements; REPORT 2020-046; Wageningen University and Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands; Wageningen Economic Research: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2020; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- HLPE. Food Losses and Waste in the Context of Sustainable Food Systems; High Level of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition; Committee on World Food Security: Rome, Italy, 2014; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuya, O.; Soma, K.; Obwanga, B. Socio-Economic Drivers of Fish Species Consumption Preferences in Kenya’s Urban Informal Food System. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termeer, E.E.W.; Soma, K.; Motovska, N.; Ayuya, O.I.; Kunz, M.; Koster, T. Sustainable Development Ensued by Social Capital Impacts on Food Insecurity: The Case of Kibera, Nairobi. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, K.; Dijkshoorn-Dekker, M.W.C.; Polman, N.B.P. Stakeholder contributions through transitions to-wards urban sustainability. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brückweh, K. The Head of Household. Administory 2016, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaney, J.A. Elements of a Neoinstitutional Environmental Economics. J. Econ. Issues 1987, 21, 1739–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; p. 357. [Google Scholar]

- Soma, K.; Vatn, A. Is there anything like a citizen? A descriptive analysis of instituting a citizen’s role to represent social values at the municipal level. Environ. Policy Gov. 2010, 20, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, K.; Obwanga, B.; Kanyuguto, C. A New Rural-Urban Fish Food System Was Established in Kenya–Learning from Best Practices. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresco, L.O.; Ruben, R.; Herens, M. Challenges and perspectives for supporting sustainable and inclusive food systems. GREAT Insights Mag 2017, 6, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Food Systems and Natural Resources. In A Report of the Working Group on Food Systems of the International Resource Panel; Westhoek, H., Ingram, J., van Berkum, S., Özay, L., Hajer, M., Eds.; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- GLOPAN. Food Systems and Diets: Facing the Challenges of the 21st Century; Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition: London, UK, 2016; p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- Béné, C.; Mehta, L.; McGranahan, G.; Cannon, T.; Gupte, J.; Tanner, T. Resilience as a policy narrative: Po-tentials and limits in the context of urban planning. Clim. Dev. 2018, 10, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Thornton, P.K.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Palmer, J.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Pradhan, P.; Barrett, C.B.; Benton, T.G.; Hall, A.; Pikaar, I. Articulating the effect of food systems innovation on the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet Planet Health 2021, 5, e50–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blay-Palmer, A.; Santini, G.; Dubbeling, M.; Renting, H.; Taguchi, M.; Giordano, T. Validating the City Region Food System Approach: Enacting Inclusive, Transformational City Region Food Systems. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide: Version 3; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project; Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2013. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14; StataCorp LP.: College Station, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gallaher, C.M. Livelihoods, Food Security and Environmental Risk: Sack Gardening in the Kibera Slums of Nairobi, Kenya. PhD Thesis, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Otene, I.J.J.; Murray, P.; Enongene, K.E. The Potential Reduction of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions from Gas Flaring in Nigeria’s Oil and Gas Industry through Alternative Productive Use. Environments 2016, 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, L.; Mishra, A.; Dubey, A.K.; Tripathi, C.; Baredar, P. Renewable energy: An overview on its contribution in current energy scenario of India. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niekerk, A.; Govender, R.; Hornsby, N.; Swart, L. Household and caregiver characteristics and behav-iours as predictors of unsafe exposure of children to para n appliances. Burns 2017, 43, 866–876. [Google Scholar]

- Chege, P.M.; Kimiywe, J.O.; Ndung’U, Z. Influence of culture on dietary practices of children under five years among Maasai pastoralists in Kajiado, Kenya. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutisya, E.; Yarime, M. Understanding the grassroots dynamics of slums in Nairobi: The dilemma of Kibera informal settlements. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2011, 2, 197–213. [Google Scholar]

- Kihato, C.W. “Go back and tell them who the real men are!” Gendering our understanding of Kibera’s post-election violence. Int. J. Confl. Violence (IJCV) 2015, 9, 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- de Smedt, J.V.A. The Nubis of Kibera: A Social History of the Nubians and Kibera Slums. Ph.D. Thesis, Leiden University,, Leiden, The Netherlands, 12 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Elfversson, E.; Höglund, K. Home of last resort: Urban land conflict and the Nubians in Kibera, Kenya. Urban Stud. 2017, 55, 1749–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chege, P.; Kuria, E.; Kimiywe, J. A comparative study on dietary practices, morbidity patterns and nutrition status of HIV/AIDS infected and non-infected pre-school children in Kibera slum, Kenya. J. Appl. Biosci. 2010, 32, 2008–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gallaher, C.M.; WinklerPrins, A.M.G.A.; Njenga, M.; Karanja, N.K. Creating Space: Sack Gardening as a Livelihood Strategy in the Kibera Slums of Nairobi, Kenya. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2015, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneri, C.W. Health Risks Associated with Wastewater Used for Irrigation in Urban Agriculture, in Nairobi Kenya. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, E.M.; Dernini, S.; Burlingame, B.; Meybeck, A.; Conforti, P. Food security and sustainability: Can one exist without the other? Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2293–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndolo, G.M. An Assessment of Clean Energy Use for Cooking in Gatwekera of Kibera, Nairobi County. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 11 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K. Clean, low-carbon but corrupt? Examining corruption risks and solutions for the renewable energy sector in Mexico, Malaysia, Kenya and South Africa. Energy Strat. Rev. 2021, 38, 100723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. Women and Men in the Informal Economy—A Statistical Picture, 3rd ed.; International Labour Office (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; p. 164. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_626831.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Mekonnen, D.A.; Termeer, E.; Soma, K.; van Berkum, S.; Piters, B.d.S. Wass How to Engage Informal Midstream Agribusiness in Enhancing Food System Outcomes: What We Know and What We Need to Know Better; Wageningen Economic Research: Wageningen, Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marusic, A.; Nielsen, W.; Ghossein, T.; Solf, S. Re-thinking the Approach to Informal Businesses: Typologies, Evidence and Future Exploration; The World Bank Group, Open Knowledge Repository: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; p. 28. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34814 (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- OECD/SWAC. Africa’s Urbanisation Dynamics; Africapolis, Mapping a New Urban Geography; West African Studies: Dakar, Senegal; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021; Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; p. 240. Available online: https://www.fao.org/publications/sofi/2021/en/ (accessed on 19 August 2022).

| Gatwekera | Kambi Muru | Karanja | Kianda | Kisumu Ndogo | Laini Saba | Lindi | Makina | Mashimoni Squatters | Olympic | Raila | Soweto West | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 34 | 30 | 30 | 35 | 28 | 35 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 33 | 35 |

| % Male | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.69 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.74 |

| Mean age | 36.8 | 43.2 | 39.5 | 31.5 | 36.8 | 37.9 | 36.1 | 36.4 | 42.1 | 33.5 | 34.2 | 38.7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soma, K.; Cornelia Johanna Janssen, V.; Ayuya, O.I.; Obwanga, B. Food Systems in Informal Urban Settlements—Exploring Differences in Livelihood Welfare Factors across Kibera, Nairobi. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141711099

Soma K, Cornelia Johanna Janssen V, Ayuya OI, Obwanga B. Food Systems in Informal Urban Settlements—Exploring Differences in Livelihood Welfare Factors across Kibera, Nairobi. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):11099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141711099

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoma, Katrine, Valerie Cornelia Johanna Janssen, Oscar Ingasia Ayuya, and Benson Obwanga. 2022. "Food Systems in Informal Urban Settlements—Exploring Differences in Livelihood Welfare Factors across Kibera, Nairobi" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 11099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141711099

APA StyleSoma, K., Cornelia Johanna Janssen, V., Ayuya, O. I., & Obwanga, B. (2022). Food Systems in Informal Urban Settlements—Exploring Differences in Livelihood Welfare Factors across Kibera, Nairobi. Sustainability, 14(17), 11099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141711099