Abstract

Sustainable entrepreneurs launch businesses to meet social and environmental needs while advancing the interests of the larger community. Sustainable entrepreneurs encounter particular difficulties when starting their businesses because of the distinction between creating and appropriating personal and social values. This study examines the effects of perceived risks and barriers on sustainable entrepreneurship through the mediating role of government support in SMEs in Algeria. This study used a quantitative research methodology that combined primary and secondary data to gather the necessary data from 230 small and medium-sized enterprise entrepreneurs through purposive sampling techniques and simple random sampling to estimate the requirements in Oran region clusters, Algeria. The proposed research model applied a structural equation model, growth path modeling analysis, correlation matrix, and analysis using the SPSS and AMOS software suites to ascertain the causal relationship between perceived risks and barriers and business performance. The main result revealed that perceived barriers impact sustainable entrepreneurship more during business startups. Likewise, perceived risk significantly affects sustainable entrepreneurship. Instead, government support has substantially mediated the relationship between perceived risk and sustainable entrepreneurship and perceived barriers. Furthermore, the diverse and complex stakeholder relationships make sustainable entrepreneurship more likely to challenge perceived risks and barriers during business startup. These results might be an essential cue for governments and private capital providers to enhance the environment for entrepreneurship.

1. Introduction

Contrary to the widely accepted role of entrepreneurship in promoting growth and bestowing economic means on a society, sustainable entrepreneurship has been thought to play the same role in generating societal prosperity during periods of abundance in urgent social and ecological needs. [1]. Prior studies revealed that sustainable entrepreneurship relates to entrepreneurial traits, such as innovation, sensitivity, and creativity [2]. In addition, entrepreneurs’ ethical concerns are growing when launching new ventures and running existing ones. Entrepreneurs who concentrate on those issues challenge their expectations about private and public benefits, the quest for capital, and the necessity of meeting the needs of others. Even though the conventional literature on entrepreneurship has a strong bias in favor of logical self-interest and the quest for individual economic gain, others regarding behavior have a long history in ethics research [3].

This study focuses on sustainable entrepreneurs who launch a venture to address social and environmental needs while advancing their and the group’s interests in Algeria. Algeria has a youthful vitality that exceeds 75% of its population. The country also has significant natural and human resources [4]. Moreover, it is the finest of Africa’s many obscure and obvious natural bounties. Similarly, many business owners have been operating SMEs for a long period of time. Oran Province’s SMEs cluster was chosen for the purpose of this study. Due to its prominence in industry, commerce, economy, culture, and government, it is one of the most significant cities in Algeria [5]. However, sustainability issues exist, and many entrepreneurs face difficulties and uncertainties. Therefore, fostering sustainable entrepreneurship will help Algeria achieve a higher level of prosperity. Sustainable entrepreneurship is the path to a society’s progress, development, and growth in all aspects. The following issue can be raised from the previous work: how might entrepreneurship serve as a key tool for developing sustainable entrepreneurship in Algeria? In order to achieve sustainable development, it is crucial to improve the environment for the development of entrepreneurial institutions and to establish a set of conditions that enable them to hold onto and grow their market shares while also having access to regional, national, and even international markets. In this situation, the Algerian government took the initiative to enact several reforms, laws, and programs.

Sustainable entrepreneurs are increasingly acknowledged for addressing current social and environmental problems [6]. These socially and environmentally conscious individuals fulfill a vital role in society because they offer solutions to complex societal issues that are overlooked, ignored, or unsuccessfully addressed by governments and incumbent businesses [7]. However, there is a lack of knowledge regarding sustainable entrepreneurs. For instance, there is still much to learn about how sustainable entrepreneurs launch their businesses and deal with challenges at the beginning. Sustainable business owners are thought to encounter unique difficulties when starting their enterprises. The disparity between the production of personal value and the production of social value may be the cause of these difficulties [8].

Even though academics are becoming more interested in sustainable entrepreneurship, more study is still needed to fully comprehend the challenges faced by sustainable entrepreneurs when starting a business. The current research answers this request. Hence, the present study examines risks and barriers to sustainable entrepreneurship when starting a business, focusing on these apparent difficulties. This study used 230 Algerian SME entrepreneurs to provide the data, which examined perceptions of entrepreneurship’s risks and barriers. Regarding obstacles, we discuss how much the institutional setting supports or hinders sustainable entrepreneurs as they launch their businesses. The perceived lack of financial resources, the perceived level of administrative procedure complexity, and the perceived scarcity of startup information are dimensions of the institutional environment. Due to the fact that they must question current laws, policies, norms, and regulations, sustainable entrepreneurs perceive financial, administrative, and informational support more negatively than regular entrepreneurs do [9].

In terms of risks, we look at the various sustainable risk types. Although scholars have argued that multiple kinds of entrepreneurs face different risks, entrepreneurs have been known to take risks [10]. Shaw and Carter [11] claim that social entrepreneurs are terrified of nonfinancial personal risks, such as the possibility of losing their network of personal connections or local credibility. This current paper distinguishes between financial and nonfinancial risks in sustainable entrepreneurs, such as potential income loss, bankruptcy, and personal failure.

This study responds to the call to investigate the added complexity of sustainable entrepreneurship [12]. To achieve this, we concentrate on the perceived risks and barriers faced by people who have recently decided to launch a business. A few significant contributions demonstrate the novelty of this current study. To advance the body of knowledge exclusively devoted to sustainable entrepreneurial activity, we first compare the perceived complexity of business startups to sustainable and conventional entrepreneurs. The significance of creating distinct support programs for entrepreneurs who are motivated to serve the desires of others compared to entrepreneurs who focus on pursuing self-interests has been supported by differences in perceived barriers and risk. Second, we discuss the heterogeneity of various risks and impediments. Our findings prove that different businessperson types have different perspectives on multiple risks. The perception of the risk of failure on a personal level seems to be especially important in sustainable entrepreneurship. Third, we further our understanding of sustainable entrepreneurship by utilizing extensive and globally comparable data. Using such data fills in the gaps in current research on sustainable entrepreneurship, where there are few empirical studies.

This study’s findings are consistent with the hypothesis that sustainable entrepreneurs have less favorable views of the administrative, financial, and informational support provided at the beginning of their businesses. Sustainable entrepreneurs are also evident in their tendency to take risks and the financial risks they face when running their businesses. Finally, this research demonstrates that sustainable entrepreneurs are more troubled by failure than conventional business owners are. Following sections on literature and hypotheses, methodology, the interpretation of the regression results, and discussion, the paper finally concludes with additional research recommendations.

2. Literature Review and Forming Hypothesis

2.1. Entrepreneurs Perceived Risk

Since early times, defining risk has been a difficult and contentious task. According to current studies in psychology and management, perceived risk is generally defined as a situation in which a decision has potential outcomes and the probability that they will occur, known as measured uncertainty [13]. Based on the expected convenience theory, risk has been defined in economics and psychology as the outcome of how people judge the likelihood and seriousness of unfavorable effects. Likewise, culturally and socially structured conceptions and assessments of phenomena, such as actions and understandings, influence risks. As opposed to this, Agustina et al. [14] claimed that the term “perception” is more frequently used in cognitive psychology, which describes how a person’s mental processes are affected by how they receive, approach, and evaluate information from their context through their senses. In the earlier scientific literature, the perception of risk has been thoroughly explored [15], particularly in relation to several factors that affect an individual’s perception of risk. This study’s main objective is to identify the characteristics of risk perception in entrepreneurship, which have been influenced by individual differences, context, how risk is processed, and how information has been communicated.

Perceived risk is an emotion- and cognition-related sensation [16]. Numerous researchers have long endorsed this comprehensive concept. This conceptualization of risk perception acknowledges the complexity of perception in risky situations. Risk perception studies have focused on a long list of risk-related problems. One issue has been brought up in another attempt to examine international risk perceptions concerning entrepreneurship. Algeria’s SMEs have low but inventive levels of perceived risk and risk-taking behavior. The concept can be defined simply as the subjective probability that an individual holds for a specific event based on those descriptions. The damage caused by the pandemic and the likelihood that the damage will occur are two of the three aspects of risk perception that we will measure in this study by asking entrepreneurs about these topics. In prior studies, entrepreneurial intention and actual entrepreneurship have been found to differ; in the former, one intends to start a business, whereas, in the latter, one has already begun a firm [17]. The relationship between risk-taking, social factors, financial considerations, and personal benefit has been examined in published studies [7]. Previous research has looked at the purpose of entrepreneurs to take on economic, social, and developmental risks to benefit themselves financially and personally [18].

2.2. Perceived Barriers of Entrepreneurs

The term “perceived barrier” refers to one’s assessment of the difficulty of social, personal, environmental, and economic barriers in a particular behavior or their desired goal status on that behavior. Furthermore, perceived barriers can influence decisions not to invest in new technologies, for instance, when a company decides not to take advantage of opportunities brought on by new kinds of order requirements due to a lack of knowledge and expertise. People who encounter perception barriers behave unreflectively, acting only in their interests and making wrong assumptions.

Perceived barriers can directly impact decisions not to invest in new technologies. For example, a company may decide not to take advantage of opportunities related to novel order requirements because it lacks the necessary knowledge and experience. Moreover, companies may be hesitant to set up their structures for future advancements in these developing technical sectors because they believe the restructuring will be excessive. This would stall SME readiness development and limit SMEs’ ability to adopt the technology. Perceived barriers account for a significant portion of the variation in behavior [19]. It is well known that those entrepreneurs’ intentions to start their businesses have been negatively influenced by perceived barriers [20]. According to findings by other researchers, entrepreneurs’ perceptions of barriers negatively affect their preferences and attitudes toward entrepreneurship [21]. Entrepreneurship faces various challenges, depending on the individual or group’s strengths.

Identifying a situation as a barrier depends on the context and can take many forms [22]. Depending on the industry sector, the location, or the type of business, there may be different entrepreneurial obstacles. Cultural, political, economic, or psychological aspects may influence these entrepreneurship obstacles. Entry versus survival barriers [23], actual versus perceived, and internal versus external barriers are some of the categories used to classify barriers in entrepreneurship [24].

The perceived internal and external entry barriers are the subjects of this study. Personality- and attitude-related walls are significantly perceived internal barriers [25]. The external barriers, which have been most commonly noticed, were related to finances [26], institutional support [27], market-related problems, such as weak networks, inadequate market knowledge, fierce competition, and difficulty finding customers [28], as well as legal and regulatory restrictions. Government red tape, taxes, and corruption [29] are state-related obstacles caused by sociopolitical, economic, and business environments [30].

2.3. Sustainable Entrepreneurship

Sustainable entrepreneurship is attracting scholarly attention in the realm of entrepreneurship education. Sustainable entrepreneurship has gained popularity in describing how entrepreneurial activities can aid in sustainable development by fusing the notions of sustainability and entrepreneurship [31]. Sustainable entrepreneurship refers to an individual’s ownership and management of a company on their account and risk. It is a difficult concept to grasp. It speaks of behavior centered on the perception and development of fresh business opportunities. Intrapreneurship, also known as corporate entrepreneurship, is a type of entrepreneurial behavior that can occur within an existing company and in creating new businesses. Individuals or business owners may include the self-employed, occupational (managerial), independent, and business owners. According to Shane [32], entrepreneurship is the academic study of how, by whom, and with what outcomes opportunities create future goods and services that are discovered, evaluated, and exploited.

The innovation, creation, and exploitation of business opportunities that advance sustainability by benefiting others in society through social and environmental benefits have been referred to as the emerging field of sustainable entrepreneurship [32]. Sustainable business owners are driven to make a difference in the complex and frequently connected social and ecological issues we face today, including long-term unemployment, climate change, and unequal healthcare and education access. They are motivated to promote sustainable development more broadly, which is understood to be the development that satisfies present-day needs without jeopardizing the ability of future generations to satiate their own needs. Furthermore, sustainable entrepreneurship is closely related to institutional, social, and environmental entrepreneurship claims [33]. We first examine how social, environmental, and sustainable entrepreneurship are similar and different to define the term. This paper discusses the connection between institutional entrepreneurship and sustainable entrepreneurship.

The desire of businesspeople to create value for others by spotting and taking advantage of opportunities arising from social issues that have not been adequately addressed by public, private, or civil society organizations is the first factor that links the fields of social, environmental, and sustainable entrepreneurship [34]. Value creation is increased societal utility by entrepreneurial activity [3]. Whatever the form of entrepreneurship, societal value creation is a prerequisite for appropriating value at the firm level. However, Santos [3] contends that each entrepreneur’s ultimate goal of value creation differs. Unlike regular businesspeople, social, environmental, and sustainable entrepreneurs also seek to improve people’s quality of life for the benefit of others as part of their mission. This contrasts with regular businesspeople, who primarily focus on creating value for their own use [35]. Due to this, the driving force behind social, environmental, and sustainable entrepreneurs differs from the one-sided pursuit of profit that usually characterizes the typical entrepreneur [36].

Secondly, despite this similarity, some key differences exist between the social, environmental, and sustainable entrepreneurship fields. These differences include the relative significance of the goals pursued and the disciplinary foundations. By addressing societal issues, such as expanding access to healthcare, sanitation, and water in slum areas and reviving underserved communities, social entrepreneurs seek to generate social benefits. Economic benefit generation frequently returns to social benefit creation in nonprofit environments [37]. It is possible to explain the nonprofit context by referring to the primary disciplinary roots of social entrepreneurship in the public and nonprofit sectors. Entrepreneurs in the environmental sector work to protect or rehabilitate our ecosystems and natural surroundings. They carry out these activities in a for-profit environment that combines the production of economic and ecological value [34], with environmental economics serving as its disciplinary basis.

Business owners prioritize a trifecta of social, environmental, and financial goals to develop future goods, procedures, and services for profit, where profit has generally been taken to comprise gains to people and society beyond money. Preserving the environment, community, and life support systems is how they define these multiple bottom lines. Hockerts and Wüstenhagen [38] assert that social and environmental entrepreneurship fields gave rise to sustainable entrepreneurship. Consequently, social and ecological entrepreneurship are sometimes defined as including sustainable entrepreneurship.

Sustainable business owners typically operate in environments where market failure and imperfections present opportunities while posing challenges that must be met [8]. Successful sustainable business owners can transform their institutional environment and implement socio-economic or political reforms. Despite their close ties, we argue that not all owners of sustainable businesses fall under the definition of institutional entrepreneurs in the sense of consciously initiating and implementing divergent changes. Institutional entrepreneurs are only those business owners whose activities directly or structurally aim at bringing about and actively implementing changes in the institutional context [39]. The coevolutionary processes and contributions of different actors in the transformation of entire industries, markets, and economies are also looked at in more recent business-related literature on the sustainability-focused transformation of society [40]. This body of literature combines processes by which established businesses transform to become more sustainable with the growth and education of new rivals or innovators. The sustainability-oriented transformation perspective strongly emphasizes the interactions between actors, as opposed to the more conventional institutional entrepreneurship approach [41].

2.4. The Effect of Perceived Barriers and Risks on Sustainable Entrepreneurship

2.4.1. The Relationship between Perceived Barriers and Sustainable Entrepreneurship

Numerous studies on sustainable entrepreneurs have looked at how important it is for them to change institutions when there are obstacles in their way. Since they negatively perceive the institutional framework for entrepreneurship, sustainable entrepreneurs struggle to launch their businesses because of financial and nonfinancial barriers. Financial obstacles have frequently been mentioned in related social and environmental entrepreneurship [8]; conversely, numerous studies on social entrepreneurship challenge securing funding [42]. The study by Leahy and Villeneuve [43] on the social enterprise coalition extensively reveals that social entrepreneurs view access to financing as a significant roadblock to their ability to expand.

Sustainable business owners deliberately locate their operations in industries with limited opportunities to capture value. This issue is connected to our claim about market flaws in the subsection below titled “challenges to sustainable entrepreneurs” [44]. Even though these business owners made this decision strategically, they still need to deal with other stakeholders when starting and expanding their businesses. Such stakeholders will probably have various interests. Hence, this may have a negative perception of these barriers regarding their commitment to and motivation for making a difference in sustainability. Since they may be motivated to overcome the difficulties mentioned above, sustainable entrepreneurs may be able to counteract the unfavorable perceptions.

Business angels, venture capital, and other private capital sources will be reluctant to invest if they cannot cover their resource commitments. Sustainable entrepreneurs may also face financial difficulties because there are no standardized metrics for how well businesses generate social value [45]. Since social entrepreneurship has its disciplinary roots in the public and nonprofit sectors, the tension between value creation and value capture (for private gain) may appear especially acute. However, for various reasons, entrepreneurship in the environmental sector is also uncertain. Academics contend that substantial value spillovers brought on by positive externalities restrict the ability of environmental entrepreneurs to capture value. Conversely, ecological economics is the disciplinary foundation of this claim [46].

Positive externalities produce significant and required societal achievements. Such societal achievements are not likely suitable for venture investing, though. The private capital provision will be constrained because of these societal benefits that cannot be taken entirely. When considering the characteristics of natural resources and environmental concerns, this problem, also referred to as the double externality problem, becomes especially crucial [47]. We also believe that a similar argument for sustainable entrepreneurs could be made by referencing the related social and ecological entrepreneurship fields. Negative perceptions of the availability of financial resources may inspire sustainable entrepreneurs to promote sustainability by creating social and environmental benefits for others in society rather than value capture for personal gain.

Although perceived nonfinancial barriers related to the institutional context in which they operate are a challenge in and of themselves, the arguments in our subsection on challenges to sustainable entrepreneurs emphasize that these barriers are particularly severe. Moreover, according to Groot and Pinkse [8], the notion that institutional entrepreneurship is a component of sustainable entrepreneurship implies that sustainable entrepreneurs face nonfinancial challenges. Sustainable business owners must avoid market imperfections, such as the monopoly power of existing players in the electrical utility industry, which restricts access to alternative energy sources. More than regular entrepreneurs, sustainable business owners deal with institutional burdens and are more likely to see barriers. This hypothesis seems to be supported by numerous empirical data. Social entrepreneurs in various developed nations struggle due to a lack of a support system [48]. As a result, social entrepreneurs lack access to knowledgeable advisors who disseminate information about best practice models and modify them for local conditions.

Similar to this, the absence of an aiding infrastructure restricts the development of social entrepreneurs and forces them to reinvent the wheel [49]. Other empirical studies suggest that startups tackling sustainability issues may need to do more administrative work. For instance, Groot and Pinkse [8] drew attention to the fact that sustainable startups depend more on government support in the form of subsidies and other incentives, which necessitates a sizable amount of paperwork and lacks transparency regarding the application process. Furthermore, more monitoring and reporting requirements by more intricate stakeholder relationships will likely add to the administrative burden of new sustainable entrepreneurs [50]. In other words, administrative processes or entrepreneurial information do not explicitly target sustainable entrepreneurs. In this study, two perceptions of infrastructure support for starting a business have been used: the perception of organizational startup complexity and insufficient startup information. People with negative opinions of these two elements are probably unsupportive of their attempts to launch a business. As a result, we came up with the following two theories:

Hypothesis 1.

Entrepreneurs committed to sustainability are more likely to overcome perceived barriers and positively influence the entrepreneurship of SMEs in Algeria.

2.4.2. Entrepreneurship Perceived Risk and Sustainable Entrepreneurship

Bringing demand and supply for goods and services together is the entrepreneur’s responsibility, who also assumes the risk associated with the venture and is responsible for keeping any profits made as a result [51]. Any theory on entrepreneurship must address risk, which can be divided into three main categories: risk attitude, actual risk, and risk insight. Risk attitude, also known as risk aversion or risk tolerance, expresses their preferred activities. While some people value taking risks, others would rather avoid them. Most people, including business owners, are comparatively risk-averse [52]. All entrepreneurs face some level of profit risk related to unpredictability regarding shifting consumer preferences, retaliating against rivals, and shifting future prices. Risk perception is the subjective measure of risk and frequently represents an inaccurate assessment of the proper degree of risk. Individuals have different perspectives on risk: there are believers and disbelievers. Risk attitudes and perceptions significantly influence new business developments [53].

We, therefore, concentrate on these two risk concepts in this study. We do not contend that sustainability affects how much risk exists. Contrary to sustainable entrepreneurs, conventional businesses that disregard sustainability issues in their operations and deny that their continued existence and expansion depend on the environment and society may expose them to greater levels of actual risk. Due to a lack of data, we cannot include the fundamental risk level in our analyses; as a result, we concentrate on people’s risk attitudes, and perceptions of risk attitudes. At the same time, we are aware that uncertainty and risk influence people’s career decisions, and the ability to manage them is necessary for entrepreneurship [52]. Different risk attitudes among people affect occupational choices and the entrepreneur’s choice of how much labor and capital to use, affecting the production scale. A group of entrepreneurs demonstrated that differences in risk-taking attitudes exist.

Block et al. [10] revealed that little research has been conducted on various entrepreneurs’ risk attitudes. They investigate whether a risk-taking attitude and the drive of the entrepreneurs at a venture startup are related. More specifically, people who start a business out of necessity are more risk averse than those who start a business to seize a perceived opportunity [10]. The delay has been intended to be turned into an opportunity for entrepreneurs who act despite the uncertainty [4]. Fundamental uncertainty is present in environmental and societal issues because it is impossible to predict the outcomes of these issues. After all, they depend on yet-to-be-determined future actions [54].

Furthermore, it is uncertain whether sustainable business practices would be rewarded by customers, markets, or governments [55]. As a result, we predict that they will face greater startup risk than their conventional counterparts, which is consistent with our earlier discussion of the additional challenges sustainable entrepreneurs face compared to regular entrepreneurs in our subsection [55]. Someone motivated to contribute to solving today’s intricately intertwined social and environmental problems must be willing to take risks first and persist in facing obstacles.

Little research has been conducted on the types of risk that entrepreneurs perceive than on people’s attitudes toward risk, which has received much attention in the literature on entrepreneurship. An entrepreneur risks losing their financial security, career prospects, relationships with their family, and mental health due to the business, social, psychological, and amicable risks they face. Depending on how they feel about risk and how they perceive the different kinds of risks involved, one’s willingness to take these risks will vary. We presume that a business owner’s motivation is influenced by how he/she sees differences. According to Block et al. [10], the risk-taking attitude of an entrepreneur is related to the entrepreneur’s motivation during a venture startup. With that in mind, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 2.

Entrepreneurs perceive risk positively affecting sustainable entrepreneurship.

2.5. The Mediation Role of Government Support

2.5.1. Entrepreneurs’ Perceived Barriers, Government Support, and Sustainable Entrepreneurship

It is widely acknowledged that entrepreneurs face significant challenges related to the small size of new businesses and a lack of resources, which may discourage would-be entrepreneurs from going down this path. It has been noted that supportive institutions and policies promote entrepreneurial activities [56]. However, such policies’ effectiveness has occasionally been disputed and seen as ineffective [57]. The goals of sustainable entrepreneurs are more expansive and intricate. They take advantage of opportunities presented by unaddressed social and environmental issues, and combine the pursuit of individual interests with those of the group’s [8]. The additional complexities have been connected to the distinction between the creation and appropriation of personal value and social value [3]. Therefore, the role of government support is so crucial. In response to this disparity, we offer three explanations for why sustainable entrepreneurs face more difficulties than conventional entrepreneurs when starting their businesses. Sustainable entrepreneurs frequently take advantage of opportunities in imperfect and falling markets [58]. Public goods, externalities, monopoly power, improper government intervention, and incomplete information are all factors in these market failures. Although pursuing these opportunities may contribute to creating private and public value [31], dealing with market failures in the context of societal and environmental problems presents additional difficulties.

On the one hand, such market failures have been related to the characteristics of natural resources and environmental concerns, such as a lack of or ambiguity in property rights, the absence of prices for specific natural resources, and exhaustibility, where use currently has an impact on next availability. In contrast, it is believed that the existence of clearly defined property rights is necessary for value appropriation and, consequently, for entrepreneurial activity. Government assistance has been deemed essential to SME performance. Administrative services may encourage entrepreneurs to complete various services, such as working environments, retail spaces, and other infrastructures [59]. Numerous researchers have looked at the extent of government support [60], which affects the rate at which SME development occurs. The government’s support significantly influences the performance of SMEs in the form of tax releases, inspiration (incentives), and an adequate control structure [61].

Hypothesis 3.

Government support has a substantial positive mediation effect on the relationship between entrepreneurs’ perceived barriers and sustainable entrepreneurship.

2.5.2. Entrepreneurs’ Perceived Risk, Government Support, and Sustainable Entrepreneurship

When starting a business, entrepreneurs must manage numerous risks and take precautions [62]. Entrepreneurs need to be constantly aware of their rivals. There may not be a market for the product if there are no rivals. The market might be saturated if there are only a few significant rivals, or the business may find a competing complex [63]. Additionally, business owners with fresh concepts and innovations should file for patents to protect their intellectual property and themselves from the gains of their rivals, who are most likely to affect them. Among the many risks that entrepreneurs must manage, in addition to bankruptcy, are financial, competitive, environmental, reputational, political, and economic risks [64]. To convince investors that they are aware of the risks, business owners must carefully plan their budget and present a realistic business plan [65]. Business owners should consider technological changes as a risk. Additionally, consumer trends are subject to rapid change, which makes market demand unpredictable and problematic for business owners. Therefore, these risks have affected sustainable entrepreneurship.

An entrepreneur will require capital to launch a business, which can come from family, loans from investors, or savings. Any new business should have a financial plan that is a component of the overall business plan and includes income projections, the sum of money required to break even, and the anticipated return on investment over the next five years. Planning incapability could put the entrepreneur in financial trouble and leave the investors with nothing. Thus, it is believed that government support is necessary for SME performance. Administrative support could promote a good corporate location, promoting the market to fully supply different services, such as office and retail space [59].

Several academics have studied the level of governmental support that affects the SME development rates [66]. The government’s support significantly influences the performance of SMEs in the form of tax releases, inspiration (incentives), and an adequate control structure [67]. Businesses need government support in various ways, including financial and nonfinancial assistance, because government involvement is not the only factor affecting SME performance. The motivation of the SME sector significantly decreases in the public-private partnership if government support for entrepreneurs has not been offered. Government support for businesses can be used to build a platform that promotes entrepreneurship, fosters R and D collaboration, and monitors the performance of SMEs [68]. Due to the multiplier effects of their integration into emerging economies, it suggests that the roles of the government and SMEs are similar to two sides of the same coin.

Additionally, fostering an atmosphere that promotes healthy competition while reducing risks could lead to government support for entrepreneurs [69]. The difficulties with fairness, laws, regulations, and tax burdens are a few of the administration’s provisional elements that hinder SME performance in the opinion of business leaders. Furthermore, no matter the economy’s state, government assistance significantly affects how well SMEs perform [70]. This study evaluated the government’s mediating effect on SME performance based on access to facilities and infrastructure. As a result, the following hypothesis has been put forth:

Hypothesis 4.

Government support substantially mediates the relationship between perceived risk-taking and sustainable entrepreneurship.

2.6. Government Support and Sustainable Entrepreneurship

As a new megatrend in the entrepreneurial path, sustainable entrepreneurship is rapidly gaining recognition in academic literature [71]. Sustainable entrepreneurship enables businesses to stand out from the competition, a source of a firm’s competitive advantage [31]. The community, environment, employees, customers, and suppliers are just a few of the dimensions that sustainable entrepreneurship encompasses [72]. For business owners, maintaining their business performance requires a safe and healthy work environment and opportunities for learning and development. As a result, in developing nations, such as Algeria, the government’s contribution to the growth of small businesses is essential.

Many researchers have observed that governments emphasize rules and regulations more than they assist entrepreneurs. The Algerian government recently offered a variety of support to help advance industrialization in the nation [73]. However, government support refers to outside assistance or support provided by various governmental institutions to aid in the development of SMEs [74]. Utilizing this assistance serves as the government’s support mechanism in the context of this study. Government assistance grants businesses access to limited, affordable resources without requiring an equivalent financial payback [75]. Most governments, especially those in developing nations, have spent a lot of time and money creating policies that support entrepreneurship [76]. Similarly, government encouragement of sustainable practices is crucial to ensuring SMEs adopt SEPs. Based on this contention, the hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 5.

Government support has a positive impact on sustainable entrepreneurship

2.7. Study’s Conceptual Framework

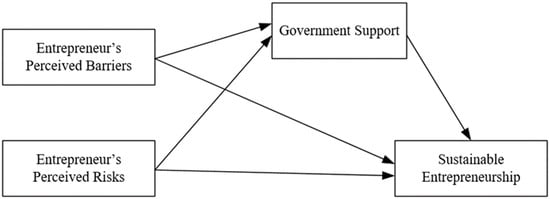

The conceptual research model for this study was constructed based on results from earlier studies. Earlier, there was a limitation in research on sustainable entrepreneurship and government support. To our knowledge, there is no similar research on sustainable entrepreneurship in Algeria. In contrast, the new contextualized insight constraints are the mediator variable, perceived risk-taking, and the barriers entrepreneurs face. Hence, sustainable entrepreneurship is the outcome variable. The entrepreneur’s perceived barriers and perceived risks are predictor variables, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Authors proposed conceptual model.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Design of the Study

A research design is used to accomplish research objectives and address issues. For this study, the quantitative research method was used. By incorporating some restrictions other scholars have not yet studied, the study created the mediator variable for government support. Researchers have examined how entrepreneurial skills play a role in mediating the relationship between government support for businesses and business performance [77]. Here, they ignored the effects of other factors, such as the perceived risk and barriers faced by entrepreneurs. They also failed to consider government assistance as a constraint on sustainable entrepreneurship mediation. Therefore, this study looks at how perceived risks and barriers to entrepreneurship affect sustainable entrepreneurship through the mediation of government support for SMEs in Algeria.

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

The researchers of this study used the purposive sampling method to determine the number of respondents from the total population [78]; thus, the estimated sample size of entrepreneurs of SMEs was taken from Oran Province, Algeria. As a result, the authors used primary and secondary data from SME entrepreneurs by choosing 230 SME entrepreneur respondents purposively. The researchers distributed 250 questionnaires to respondents. Finally, 230 questionnaires were collected and analyzed using SPSS/AMOS statistical tools.

3.3. Measurement Items

The study’s questionnaires were adapted from previous studies. The study used a five-point Likert scale for each dependent variable, independent variable, and mediating variable. There were 19 statement assessment items about the variables chosen for this study and four construct variables. Sustainable business practices were the dependent variables in this investigation. These variables’ measuring tools were altered based on results that had already been confirmed. Additionally, five contextualized items were assessed using questions with predefined five-point Likert scales. In this study, perceived risks and barriers faced by entrepreneurs were examined to achieve the study’s goals. Government support has been chosen as the final mediator variable.

4. Results and Interpretations

4.1. Demographic Data Analysis

This study’s 55.2% (127) respondents were male SME entrepreneurs. Some 103 (44.8%) of the respondents were female SME entrepreneurs. From the statistics, we understand that women participate in society in relatively good proportions; this may be due to the ability of SMEs to take into account the involvement of female entrepreneurs. According to the data analysis, 20–29-year-olds made up 36% of the entrepreneurs who responded, followed by 30–39-year-olds at 23%, 40–49-year-olds at 17%, over-50-year-olds at 13.1%, and over-50-year-olds at 10.8% of the respondents. It demonstrates that two-thirds of the participants were experienced business people who could provide a thoughtful response to the study.

According to the respondents’ responses regarding their educational backgrounds, 18.9% of them had completed secondary school, 35% had earned diplomas, 25.5% had completed their undergraduate degrees, and 20.6% had completed their post-graduate degrees. The analysis, therefore, suggests that the majority of the participants were able to contribute valuable evidence to the study. Additionally, according to the respondents’ work history, 18.5% had more than 21 years of service performing SME business tasks, while 54.9% had 11–20 years of work experience. The remaining respondents, who had 6–10 and 1–5 years of business experience, made up the remaining 11.7 and 3% of the sample, respectively.

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

Convergent and discriminant validity were used to evaluate the measurement model’s quality to determine the items’ construct validity and reliability [79]. Convergent validity is the extent to which multiple items measuring the same construct share significant variance in standard [80]. When the AVE is less than zero (0), it is clear that the constructs can account for more indicator errors than the variance. All variables in this study had an AVE of greater than 0.50. Therefore, it could be stated that those are accurate indicators.

4.2.1. Reliability and Discriminant Validity Test

In this study, all relevant questionnaire questions were evaluated using the statistical program SPSS/AMOS 23 to ensure they met the validity and reliability standards. The model fit indices were also assessed, validated, and tested using all popular tests for validity, reliability, discriminative validity, and multidimensionality checking. As a result, the study determined the extracted results’ average variance, loading factor, composite reliability (C.R), and Cronbach alpha (AVE). All variables’ Cronbach alpha coefficient values fell within the range of 0.765–0.893, more significant than the recommended value of 0.70 [81]. As a result, the result shows that the estimated values exceeded the calculated variance value in terms of internal consistency, reliability, and validity. The factor analysis also seeks to identify unaccounted-for factors that affect how different observations co-variate. Factor-loading values can represent the variance a variable on a specific element can explain. The factor takes enough variance from the variable using a structural equation modeling technique when the factor loading is 0.70 or higher. Therefore, it is more likely that the estimated factor loading values for the entire variable, which range from 0.709 to 0.869, are significant, proving the measurement constructs’ strong convergent validity.

Furthermore, all estimated CR values for latent constructs were above the critical ratio’s acceptable level of reliability of 0.70, ranging from 0.849 to 0.921 [82]. The regressed weighted essential balance greater than 1.96 was regarded as a significant parameter at a p-value of 0.05. Since the level of AVE is higher than the recommended value of 0.50, which is considered very good and acceptable [81], the estimated (AVE) values for the entire derived construct ranged from 0.584 to 0.70. This demonstrates that each research variable’s characteristics could be more accurately reflected by the measuring questions used in the conceptual model for the study and as displayed in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Reliability and validity test analysis.

4.2.2. Discriminant Validity and the Correlation Matrix

The covariance values indicate a significant correlation between the constructs and the outcome variable, sustainable entrepreneurship, perceived barriers by the entrepreneur, perceived risk by the entrepreneur, and government support Appendix A. All independent and dependent variables have a positive and significant relationship, according to the (AVE) of the observed variables, at p < 0.05. The covariance values, therefore, showed that all constructs are related. Additionally, the entrepreneur perceives risk-taking and barriers to the outcome variable, sustainable entrepreneurship (SUES). As shown in Table 2, the mediation variable government support (GOVS) also supports the relationships between the variables.

Table 2.

Correlations matrix and discriminant validity results analysis.

4.3. Analysis of Multiple Regressions

This study used multiple regression analysis to pinpoint the responsive factors that affect enterprise performance results. A hugely important and beneficial relationship exists between the characteristics of an entrepreneur’s perceived risk, an entrepreneur’s barriers, and government support for sustainable entrepreneurship. Regression results show that the estimated values of each parameter range from 0.236 (GOVS), 0.263 (EPB), to 0.427 (EPR) with SUES. The mediator role of government support helps to explain the indirect significant and positive impact among variables, and the parameter estimate value ranges from 0.276 (EPB) to 0.661 (EPR) with (GOVS). When the estimates are divided, their appropriate standard errors (S.E.) are examined, and crucial ratio values are produced (C.R). At a significance level of 0.05, a critical ratio score above 1.96 increases the likelihood that the result will be positive. The data demonstrated that every study’s limitation is significant at a p-value of 0.05.

Each determined variable underwent independent testing to ensure that the proposed research model adheres to the previously stated assumptions. The outcome variable, sustainable entrepreneurship, was positively and significantly impacted by the predictor variables entrepreneur’s perceived barrier (EPB) and entrepreneur’s perceived risk (EPR), with a p-value of 0.000. Furthermore, the mediator variable, government support (GOVS), with a p-value of 0.000, significantly and positively influenced the dependent variable, sustainable entrepreneurship (SUES). This shows that the variances in the study variables across all dimensions are not entirely different. Therefore, government support (GOVS) is more likely to positively and significantly affect sustainable entrepreneurship (SUES), as shown in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Regression weights for significant and critical ratio levels.

4.4. Structural Equation Model Estimate

This study employed a structural equation model with a supportive path diagram to assess the effects of the response variables on the dependent variables. The structural equation (SEM) model estimation summarized and demonstrated that the goodness of model fit indices is acceptable as long as they all exceed the threshold values of fundamental assumptions. Additionally, the model’s chi-square is less than 3.0 at 1.74, and the GFI fits at 0.931, higher than the 0.90 thresholds. The model’s IFI is 0.951, above the recommended value of greater than 0.90, and the AGFI is acceptable at 0.916, above the recommended value of 0.90. The NFI value is also 0.905, above 0.90. The model’s CFI is 0.961, or 0.90, and its TLI is 0.907, or 0.90. Hence, Table 4 shows the summary of model fit indices.

Table 4.

Summary of model fit indices.

4.5. Results of the Path Modeling and Goodness-of-Fit Analysis of the Structural Model

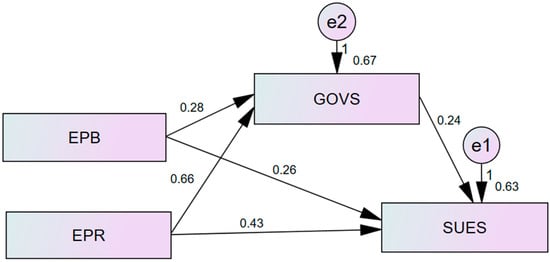

This study assessed the goodness-of-fit and effects of constructs on the corresponding variables using the structural equation and growth path models. Additionally, the explained variance of model fitness based on the outcomes of the path-modeling diagram analysis and the estimated values of the growth path modeling coefficients or standardized regression weights of 0.667 (67%) were taken into account in the study (R2). The growth path model revealed that the independent variable, entrepreneur perceived barrier (β = 0.263 ***), was significant at a p-value of 0.000. As a result, the estimated values for the variable from the standardized coefficient regression suggest that the model is fit because R square (R2) is estimated to be 0.63 (63%), and significant at a p-value of 0.000. As shown in Figure 2, the perceived risk of the entrepreneur (β = 0.427 ***) has a substantial impact on the outcome variable of sustainable entrepreneurship, which is strongly mediated by government support (β = 0.236 ***). As a result, the government’s role in supporting entrepreneurship among SMEs in Algeria is significant.

Figure 2.

Standardized path coefficients and significance of the structural equation model.

On the other hand, the impact of every constraint variable on sustainable entrepreneurship has multiplied. Whereas others stay constant, the outcome variable sustainable entrepreneurship (SUES) rises by an estimated factor of (β = 0.263, significantly, with a p-value of 0.000). When the impact of perceived risk (EPR) increases by one unit, the outcome variable, sustainable entrepreneurship (SUES), significantly improves by an estimated factor of (β = 0.427 with a p-value of 0.000). Additionally, the estimated factor of (β = 0.236 at a p-value of 0.000) will substantially affect the overall sustainable entrepreneurship of SMEs because it significantly strengthens the mediating effect of government support on other constraints, such as the entrepreneur’s perceived barrier and risk. Government support mediates between independent and dependent variables, as shown by the suggested conceptual model fit indices in Figure 2.

4.6. The Mediator Variable’s Direct, Indirect, and Total Effects

The growth path model was used in this study to look at how the study variable affected mediation. Path modeling regression weight analysis was used to assess the mediator variable’s direct, indirect, and cumulative effects on support. The structural equation model considered and balanced all the independent factors that were added to the outcome variable’s mediation effects (SEM). The different mediation results demonstrate the cumulative, direct, and indirect effects of the mediator variable government support. The mediation weights can now account for two points of view, according to the findings of the development path modeling. The first examines how the government acts as an intermediary and how each independent factor influences things. The mediating effects of government support on entrepreneurs’ perceived barriers and risks were positive and significant at (β = 0.276, β = 0. 0.661), respectively. The results imply that government assistance significantly affects how entrepreneurs perceive risks and barriers. The second aspect that needs to be examined is how support from the government affects sustainable entrepreneurship. This positively and significantly influences government support for sustainable entrepreneurship, encouraging total effects (β = 0.66). In summary, the mediating effects of government support and all independent factors on the enterprise performance outcomes were highly significant and positive in all direct, indirect, and total effects measurements. Therefore, as shown in Table 5 below, the government’s mediation role was beneficial.

Table 5.

The direct, indirect, and total effects.

4.7. Mediating Effects of Government Support

As shown in the Table 5, government support has been used in this study as a mediator variable to investigate the effects of entrepreneurs’ perceived barriers and risks on sustainable entrepreneurship. The Sobel test was used to examine the impact of the mediating variables and determine how effective they were at catalyzing other established predictors and outcome variables. Therefore, mediating effects occur when the Z-score exceeds 2.00 (absolute value) [83,84]. Table 6 below demonstrates that the Sobel test’s Z-score value met the 2.00 threshold requirement and that the other study variables were strongly supported by the mediating effects of government support in their intervening role.

Table 6.

Results of the mediation effects of government support.

4.8. Hypothesis Test Analysis and Decision

This research attempted to formulate and test five hypotheses per the study’s objectives. The entire predicted hypothesis was also developed using the literature and empirical research. According to the study’s hypothesis test findings, the perceived barrier faced by entrepreneurs has a positive and significant effect on sustainable entrepreneurship, with an estimated value of (β = 0.263 ***; p = 0.000), and the proposed H1 is, therefore, supported. Likewise, the entrepreneur’s perceived risk positively and substantially influences sustainable entrepreneurship with estimation values of (β = 0.427 ***; p = 0.000), so H2 is supported. Government support also affects perceived barriers, as shown by estimation values (β = 0.276; p = 0.000), which offer a positive and significant influence of government support on perceived barriers of entrepreneurs. Government support also affects how people perceive risk, and the typical estimation values show that this influence was positive and significant (β = 0.661 **; p = 0.000). Therefore, H3 and H4 have also been supported.

Furthermore, with the estimation values (β = 0.236 ***; p = 0.001), the mediator variable government support directly and significantly positively affects sustainable entrepreneurship, supporting the proposed H5. As a result, each stated hypothesis significantly and positively impacted the model. This study sought to fill in some of these gaps by providing evidence to support speculative conclusions about the influence of perceived risks and barriers on the long-term sustainability of entrepreneurship among SMEs in Algeria. As a result, it has been discovered that every developed and tested hypothesis contributed significantly and positively to the success of sustainable entrepreneurship. As a result, the resulting hypotheses have been supported, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Summary of hypothesized results.

5. Discussion

Unlike the widely acknowledged role of entrepreneurship in fostering growth and bestowing economic wealth in a society, sustainable entrepreneurship is thought to play the same role in generating societal wealth during periods of abundance in urgent social and ecological needs [85]. Regardless of the growing interest in sustainable entrepreneurship among academics, more research is still needed to fully comprehend sustainable entrepreneurs’ challenges when opening a business [12]. The present study responds to this question. We begin by claiming that sustainable entrepreneurs face more difficulties in the startup business phase, defined by the simultaneous pursuit of individual and collective goals. We suggest sustainable entrepreneurs face more institutional barriers and risks when starting a business because they operate in critical institutional contexts, require a broad knowledge base, and use imperfect markets. In terms of financial and, primarily, nonfinancial barriers, our research shows that sustainable entrepreneurs are more critical of the startup environment. This is based on an entrepreneurship survey that gathers data on business owners’ startup motivations, barriers to entrepreneurship, and risk factors in Algeria.

Environmentally conscious entrepreneurs are significantly more willing to take financial risks. One of the initial initiatives to pinpoint various risk attitudes of the entrepreneurs under investigation is this current paper. We find that entrepreneurs’ willingness to take risks is remarkably sustainable. Therefore, when we view the topic of risk from a broader perspective, our findings are consistent with the idea that sustainable entrepreneurs face various risks when they launch a business. We found evidence to support the claim that sustainable entrepreneurs fear failure more than conventional entrepreneurs. Since they have to handle increasingly complicated stakeholder relationships while questioning laws, rules, and norms, sustainable entrepreneurs risk losing their credibility and reputation.

Our findings from this study suggest that further investigation might establish whether a coping mechanism for long-term financial risks exists. More specifically, by being motivated to overcome the challenges they expect to face during the startup process, sustainable entrepreneurs may become less afraid of taking financial risks. It would be intriguing to investigate the function of altruistic behavior and group interests in this context instead of rational self-interest. The current study significantly advances our knowledge of sustainable entrepreneurs, particularly concerning how they perceive the startup process. We highlight the significance of the risk of failure in various types of risk. Different supportive strategies have been needed to address the risk of personal failure, especially when teaching entrepreneurial skills, such as networking or building and maintaining relationships with stakeholders. Furthermore, specialized training programs for aspiring sustainable entrepreneurs could increase awareness of environmental and social issues’ specifics and other challenges.

Our results have implications for how we understand how various types of entrepreneurs move through the entrepreneurial process from a (future) research perspective [86]. According to earlier studies, the later, more advanced stages of the entrepreneurial process are when social entrepreneurs tend to be less active. There is proof that entrepreneurs may not fully engage in the entrepreneurial process as they want [87]. Future studies may look at how perceptions of startups affect sustainable entrepreneurs’ experiences as their businesses grow, taking various performance measures into account. Earlier studies [88] focused on the relationship between perceived barriers and entrepreneurial intentions.

6. Conclusions and Recommendation

This study’s primary objective was to investigate how perceived barriers and risks affect sustainable entrepreneurship in Algeria’s SME owners, with government support as a mediating factor. In this study, quantitative research methods were used. The developed research model used multiple regression analysis, growth path modeling, a structural equation model, and SPSS/AMOS statistical tools. Additionally, the study drew on primary and secondary data sources from chosen entrepreneurs. The study reached the following important conclusions based on the findings and the reviewed literature.

Theoretical ramifications suggest that the mediating role of government support has substantial, significant, and positive impacts on sustainable entrepreneurship (β = 0.236 and R2 = 0.67), consistent with the study’s findings. The derived conceptual model satisfied all suggested model index values and fit significantly and favorably. Additionally, the independent variables perceived barrier by the entrepreneur (β = 0.263) and perceived risk by the entrepreneur (β = 0.427) have a favorable and significant impact on sustainable entrepreneurship. However, each indicator measurement item positively affects the receptive response and outcome variable. Mainly, the perception of risk by the entrepreneur (β = 0.427) has a significant effect on sustainable entrepreneurship. The conclusions of the results have substantial and advantageous effects on theoretical implications.

Theoretical Implication: This study’s findings agree with earlier research from a rational and theoretical perspective. According to the sustainability theory, an entrepreneur’s financial constraints can be alleviated by long-term loan options, access to leased equipment, and access to workspaces via a cluster approach, all of which have an impact on (future) research as well as the educational system, the support system, and other areas. Our study suggests that sustainable entrepreneurs perceive a greater degree of institutional support deficiency than conventional entrepreneurs by comparing perceived risks and barriers to those perceived risks. Therefore, this study’s theoretical implications should be discussed in light of resource-based theory.

Managerial Implications: This study’s findings have crucial implications for governments and private financiers that want to support sustainable entrepreneurship. It is necessary to improve the climate for new businesses, and targeted support initiatives for launching long-term businesses seem justified. Further encouragement should be given to specialized support systems, such as sustainable incubators and investment funds for sustainable startups. Furthermore, subsidy providers could re-evaluate the associated administrative constraints by aiding startups in their application procedure. Additionally, the study’s findings and their managerial ramifications demonstrate how important this finding is for those who want to support sustainable entrepreneurship, such as governments and private capital providers. It is necessary to improve the startup environment, and targeted support initiatives for budding sustainable entrepreneurs seem justified. Specialized support systems, such as incubators for sustainable startups and investment funds, must be encouraged more. Subsidy providers could also reassess the associated administrative costs by assisting startups with their application process.

Limitations and future directions: This study’s primary limitation is that SME entrepreneurs are its only focus. Algeria, particularly in the purposive prominent entrepreneurs of SME clusters, was the sole focus of this study. Other limitations have not been taken into account in this study. The use of secondary data to assess the financial facets of enterprise performance is also constrained. All of this suggests that additional research should be conducted.

The Study’s Future Directions: We suggest a few additional potential research areas. Research could focus on the actual outcomes of sustainable entrepreneurial activities and the degree to which the goals of the sustainable entrepreneur in terms of social value creation are achievable. Taking into account a variety of sustainable businesses might be a different strategy. It is possible to consider the difference between sustainable and conventional businesses as a continuum with various dimensions; sustainable businesses may differ in the degree to which they set social and environmental goals, as well as in terms of their level of innovation and desire to produce the right kind of value. In this current study, we used four ordinal categories to address the diversity among entrepreneurs regarding the significance of addressing unmet environmental and social needs at startups. It would be interesting to see more detailed typologies which consider the desire to satisfy one’s own needs and those of others. Examining country differences in-depth would be another potential direction for future research. Although our primary analysis used a large sample, one of the additional analyses revealed variations across geographic regions, such as in risk-taking propensity. To better understand sustainable entrepreneurship, it may be helpful to have a clear overview of regional differences and an explanation. Finally, we would like to emphasize how important it is to comprehend the complexities of the risks and barriers that sustainable entrepreneurs face, as well as the significance of the institutional startup climate, given the growing interest in the role of entrepreneurs in the diffusion of innovations and their contribution to a more sustainable society.

All parties involved in enterprise development should act under their individual and shared responsibilities. Obtaining long-term loan financing, balancing unfair interest rates, providing long-term machine lease systems, redefining small and microenterprises practically, and formulating suitable clustering management approaches are other recommendations offered by this study for the government. These actions must address the sustainable issues that SME entrepreneurs are currently facing. The government should evaluate the implementation of the SME policy and strategy in light of the primary legitimate institutions interested in job creation. As a result, more research should be conducted, and the government and institutions should have experience resolving issues using research-based investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.P. and L.W.; methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resource, data curation, and writing—original draft preparation, L.W.; writing—review, editing, and supervision, H.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding sources.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

First, we would like to thank the respondents who provided accurate data for our study. Furthermore, we would like to thank the School of Management at the Wuhan University of Technology for their continuous support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurements Construct Items.

Table A1.

Measurements Construct Items.

| Variables | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| (1) My company must support the well-being of its employees. | ||

| (2) Our company needs to participate in community development actively. | ||

| Sustainable Entrepreneurship | (3) Our products and services are meant to be harmless regarding environmental issues. | [71] |

| (4) Our company needs to establish long-term connections with partners in our market (s). | ||

| (5) For our company to achieve tenable economic goals, operating within the business networks is essential. | ||

| (1) It is challenging to start one’s own business due to a lack of available financial support. | ||

| (2) It is not easy to start one’s own business due to the complex administrative procedures. | ||

| Perceived Barriers | (3) Finding enough information on how to launch a business is challenging. | [89] |

| (4) I lack the necessary knowledge and expertise. | ||

| (5) lack of startup information, willingness to take risks. | ||

| (1) In general, I am willing to take risks. | ||

| (2) The risks of a business that I set up is what I am most afraid of. | ||

| Perceived Risks | (3) To assume responsibility for the environment or society, our company invests in green. | [90] |

| (4) I find it very hard on my present income | ||

| (5) I faced bankruptcy. | ||

| (1) Facilitating training. | ||

| (2) Facilitating working and selling place. | ||

| Government Support | [68] | |

| (3) Issued supportive policy. | ||

| (4) Facilitating financial support. |

References

- Savrul, M. The impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth: GEM data analysis. J. Manag. Mark. Logist. 2017, 4, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, R.A.; Rosenthal, S.B. The spirit of entrepreneurship and the qualities of moral decision-making: Toward a uni-fying framework. J. Bus. Ethics. 2005, 60, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.M. A positive theory of social entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ethics. 2012, 111, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samia, K.; Wahiba, Z. Entrepreneurship a Pivotal Mechanism for Achieving Sustainable Development in Algeria (Reality and Expectations). J. Bus. Trade Econ. 2021, 6, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Khaidher, K.; Safi, W.; Eneizan, B. Small and Medium Enterprises as a Strategic Choice for Development Case Study of Algeria. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. 2019, 9, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorio, A.M.; Puumalainen, K.; Fellnhofer, K. Drivers of entrepreneurial intentions in sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behave. Res. 2017, 24, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn, B.; Van der Zwan, P.; Thurik, R. Sustainable entrepreneurship: The role of perceived barriers and risk. J. Bus. Ethics. 2019, 157, 1133–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkse, J.; Groot, K. Sustainable entrepreneurship and corporate political activity: Overcoming market barriers in the clean energy sector. J. Entrep Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 633–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kury, K.W. Sustainability meets social entrepreneurship: A path to social change through institutional entrepreneurship. Int. J. Bus. Insights Transform. 2012, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Block, J.; Sandner, P.; Spiegel, F. How do risk attitudes differ within the group of entrepreneurs? The role of motivation and procedural utility. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E.; Carter, S. Social entrepreneurship: Theoretical antecedents and empirical analysis of entrepreneurial processes and outcomes. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2007, 14, 418–434. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M.I. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, K.; Larsen, S.; Øgaard, T. How to define and measure risk perceptions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustina, I.; Ajis, M.N.E.B.; Pradesa, H.A. Entrepreneur’s perceived risk and risk-taking behaviour in the small-sized cre-ative businesses of the tourism sector during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Manag. 2021, 18, 187–209. [Google Scholar]

- Renn, O.; Burns, W.J.; Kasperson, J.X.; Kasperson, R.E.; Slovic, P. The social amplification of risk: Theoretical foundations and empirical applications. J. Soc. Issues 1992, 48, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arin, A.T. Persepsi risiko di Indonesia: Tinjauan kualitatif sistematik. Bul. Psikol. 2016, 20, 66–81. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelfattah, F.; Al Halbusi, H.; Al-Brwani, R.M. Influence of self-perceived creativity and social media use in predicting E-entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2022, 6, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutzler, J.; Andonova, V.; Diaz-Serrano, L. How context shapes entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a driver of entrepre-neurial intentions: A multilevel approach. Entrepreneur. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 880–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, N.; Lytle, L.A.; Komro, K.A. Applying the theory of planned behaviour to fruit and vegetable consumption of young adolescents. Am. J. Health. Promote. 2002, 16, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, M.; Shinnar, R.; Toney, B.; Llopis, F.; Fox, J. Explaining entrepreneurial intentions of university students: A cross-cultural study. Int. J. Entrep. Behave. Res. 2009, 15, 571–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebaili, B.; Al-Subyae, S.S.; Al-Qahtani, F. Barriers to entrepreneurial intention among Qatari male students. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2017, 24, 833–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katundu, M.A.; Gabagambi, D.M. Barriers to business startup among Tanzanian university graduates: Evidence from the University of Dar-es-salaam. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2016, 17, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeesi, R.; Dastranj, M.; Mohammadi, S.; Rasouli, E. Understanding the interactions among the barriers to entrepreneurship using interpretive structural mod-elling. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaridis, I.K.; Kitsios, F. Students’ perceptions of barriers to entrepreneurship. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2017, 1, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakovleva, T.; Solesvik, M.Z. Entrepreneurial intentions in post-Soviet economies. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2014, 21, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G.O.; Boateng, A.A.; Bampoe, H.S. Barriers to youthful entrepreneurship in rural areas of Ghana. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2014, 8, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Şeşen, H.; Pruett, M. The impact of education, economy and culture on entrepreneurial motives, barriers and intentions: A comparative study of the United States and Turkey. J. Entrepreneurship. 2014, 23, 231–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, M.; Nduro, K. Polytechnic Students’ Entrepreneurial Knowledge, Preferences and Perceived Barriers to Start–Up Business. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2015, 7, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, M.M.; Chowdhury, M.M.; Ullah, M.M. Barriers and incentives for youth entrepreneurship startups: Evidence from Bangladesh. Glob. Manag. Bus. Res. 2015, 15, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ozaralli, N.; Rivenburgh, N.K. Entrepreneurial intention: Antecedents to entrepreneurial behaviour in the USA and Tur-key. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2016, 6, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Janssen, F.; Nicolopoulou, K.; Hockerts, K. Advancing sustainable entrepreneurship through substantive research. Int. J. Entrep. Behave. Res. 2018, 24, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.G.; O’Neil, I.; Sarasvathy, S.D. Exploring environmental entrepreneurship: Identity coupling, venture goals, and stakeholder incentives. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 695–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelken, H.N.; de Jong, G. The impact of values and future orientation on intention formation within sustainable entre-preneurship. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 122052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacin, P.A.; Dacin, M.T.; Matear, M. Social entrepreneurship: Why we do not need a new theory and how we move for-ward from here. Acad. Manag. Perspective. 2010, 24, 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, N.; Kiefer, K.; York, J.G. Distinctions Not Dichotomies: Exploring Social, Sustainable, and Environmental Entre-Preneurship in Social and Sustainable Entrepreneurship; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hockerts, K.; Wüstenhagen, R. Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids: Theorizing the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 481–492. [Google Scholar]

- Battilana, J.; Leca, B.; Boxenbaum, E. How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Annals. 2009, 3, 65–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.G.; Schaltegger, S. 100 per cent organic? A sustainable entrepreneurship perspective on the diffusion of organic clothing. Corp. Gov. 2013, 13, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, S.; Andrachuk, M.; Carey, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Schroeder, H.; Mischkowski, N.; Loorbach, D. Governing and accelerating transformative entrepreneurship: Exploring the potential for small business innovation on urban sustainability transitions. Curr. Opin. Enviro. Sustain. 2016, 22, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newey, L.R.; Zahra, S.A. The evolving firm: How dynamic and operating capabilities interact to enable entrepreneurship. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, S81–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, G.; Villeneuve-Smith, F. State of a Social Enterprise Survey; Social Enterprise Coalition: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin, G.; Bacq, S.; Pidduck, R.J. Where change happens: Community-level phenomena in social entrepreneurship re-search. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2018, 56, 24–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, S.A.; Wright, M. Understanding the social role of entrepreneurship. J. Manage. Stud. 2016, 53, 610–629. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rijnsoever, F.J. Intermediaries for the greater good: How entrepreneurial support organizations can embed con-strained sustainable development startups in entrepreneurial ecosystems. Res. Policy. 2022, 51, 104438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.B.; Newell, R.G.; Stavins, R.N. A tale of two market failures: Technol. Environ. Policy. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 54, 164–174. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, A.; Anwar, N.; Yasmin, F.; Islam, M.A. An exploratory study toward understanding social entrepreneurial intention. J. Int. Bus. Manag. 2018, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]