Abstract

Hydropower engineering has brought unprecedented benefits to the world while causing massive displacement of people. Since the implementation of the Post-Relocation Support (PReS) policy for reservoir resettlers in China in 2006, the distribution of perceived livelihood resilience by gender of resettlers has gradually become more equal. Based on data from a survey of rural reservoir resettlers’ livelihoods in nine regions of Guizhou Province, China, this data examines the distribution of resettlers’ perceived livelihood resilience across genders using logit regression and then explores the contribution to gender equality. The empirical results show that, unlike previous studies, household economic conditions do not bring about more gender differences in perceived livelihood resilience among resettlers (gender contribution ratio = 1.12). Gender differences in perceived livelihood resilience among resettlers were influenced by household workforce levels (e.g., gender contribution ratio = 1.23 at high workforce levels), education level (e.g., contribution ratio = 1.87 in primary education), and resettlement methods (e.g., contribution ratio = 4.53 at external resettlement). The implementation of the PReS policy also contributes to the gender equality of these resettlers’ perceived livelihood resilience. For rural resettlers in different regions with different livelihoods, resettlement patterns, capital, and gender differences of resettlers should be understood through different livelihood resilience perspectives. Improving capacity building of resettlers’ livelihoods resilience through site-specific, participatory development and resource interoperability to promote high quality, sustainable and simultaneous development in resettlement areas and reservoirs.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the concept of resilience has become “a pervasive idiom of global sustainable governance” [1]. Discussions on resilience have also gradually risen to the top of the international policy agenda [2]. In today’s era of political, cultural and economic diversity, the term resilience has become a dynamic process, and the form and degree of its change are influenced by the instability and diversity of key elements in the external environmental system [3]. Many important perspectives of resilience focus on human livelihoods [4]. The resettlement of populations as they move between different regions and their socioeconomic recovery and reconstruction activities is a global challenge. Unmitigated and unmanaged, the resettlement effect is very likely to generate ‘new poverty’ among the displaced people, greater than their ‘predisplacement poverty.’ [5]. Resettlement might also lead to short term, relative deprivation for resettled people and their host communities [6]. Impoverishment of displaced people is the central risk in development caused by involuntary population resettlement. To counter this central risk, protecting and reconstructing displaced peoples’ livelihoods is the central requirement for equitable resettlement programs [7]. Impoverishment includes multiple variants: landlessness, homelessness, joblessness, food insecurity, erosion of health conditions, marginalization (downward mobility), and social disarticulation, including disruption of educational opportunities [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Empirical evidence shows that the risks of impoverishment and social disruption turn into a grim reality. In India, for instance, researchers found that the country’s development programs have caused the displacement and involuntary resettlement of approximately 20 million people over roughly four decades, but that as many as 75% of these people have not been “rehabilitated” [7]. Their incomes and livelihoods have not been restored. This is the very important driving force to the Resettlement Act that was launched in 2013 [13].

The dam is a very important national infrastructure for hydropower, irrigation, water supply and flood defence. During the first 30 years since the founding of PRC, the total number of reservoirs rose from 1200 to more than 83,000, and to date, there have been more than 98,500 dams, which have resulted in an estimated 24.9 million resettlers [14]. Resettlement is considered the greatest challenge for building dams [15]. Dam construction has forced significant numbers of residents to leave their homes and relocate to accommodate dam construction [16]. The research shows that reservoir resettlers would have caused the overall decline of resettlers’ livelihood capital. The prominent problem is that the reduction in land resources and population relocation leads to the changes of resettlers’ livelihood diversification and lifestyle change, which puts forward new requirements for the improvement of job skills and personal capability [17].

Large dams and reservoirs typically occupy vast lots of rural land and trigger resettlement on a massive scale. The rapid economic growth and social structure changes have driven a transition from “rural China” to “urban–rural China”. Population expansion, urbanization, industrialization, and modern infrastructure construction have deepened the tension of human land interaction and formed a pattern of the land-based development [14]. It always requires more space for city, industry and residential areas through taking more farmland from peasants. Land acquisition and resettlement are the core content of China’s land-related laws. As government and society focused on land issues, land expropriation and resettlement accordingly provoked more attention [18]. Land acquisition for construction not only needs to consider land occupation, but also should properly arrange the production, livelihoods, and equity [11,19].

The purpose of resettlement is to effectively reduce family risk and maintain living standards. However, it is unknown whether resettlers can adapt to the new environment after experiencing relocation. Studies have pointed out that most of the efforts to measure livelihood rely only on objective measures of resilience, although many efforts to measure livelihood resilience ignore human initiative, namely, subjective perception [4]. Research on perceived livelihood resilience has previously often used surveys or focus groups for data collection, which are only suitable for assessing the subjective perception of individuals, rather than a particular group. As stated, this approach is usually limited to one resilience capacity, challenge or function. Subjective perceptions of resilience may be largely ignored [20,21,22]. Livelihood resilience emphasises human initiative because human actors have information processing capabilities and their ability to participate in purposeful action and reflective learning [23]. It was noted that rural resettlers will become vulnerable to new environments, and therefore, their resilience to livelihood risks may fall dramatically [24,25]. Some researchers also recognize that the overall impact of resettlement on livelihoods is only understood many years after resettlement occurs [26,27,28]. Reconstruction and improving the livelihoods of displaced persons require clear strategies to mitigate risk with adequate financial support [7]. Whether resettlement has significantly improved livelihood resilience and reduced vulnerability after resettlement is a question that requires more time and empirical evidence to answer. Moreover, in the perceived measure of livelihood resilience among resettlers, most of the discussions have occurred in the community or within a larger macro system, often ignoring the perception of resilience of families and groups. More importantly, little is known about the importance of perceived levels of livelihood resilience in resettlement by gender. Analyses are also often limited to brief discussions and basic descriptions [29], including land acquisition and asset ownership [30]. However, the lack of land rights and interests and the partial deprivation of survival rights caused by resettlement make female immigrants have to rely more on male families for their livelihood. However, due to the lack of land rights and the partial deprivation of subsistence rights caused by resettlement, female resettlers have to rely more on male families for their livelihood [31]. Studies have shown that male and female resettlers are significantly different in their ability to adapt to society after resettlement [32]. Therefore, whether there is an equal perception of livelihood resilience in terms of gender requires further examination, and judging gender equality in the perceived situation of livelihood resilience helps to assess whether resettlers can be sustainable and better integrate into local life.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Livelihood Resilience and Perception

Livelihood is often understood as the way of earning a living based on capacity, assets and activities, which is reflected in the family’s choice of livelihood behaviour based on capacity and assets [33]. Consider resilience as a capability, that systems and related processes are not static but rather constantly changing and evolving and that they cannot be regarded as a result that can be measured quantitatively [34]. Livelihood resilience is about people making a living and ensuring their well-being [35,36,37]. Which defined as the process of families and communities coping, recovering, learning changes and interference, and changing their livelihood patterns to adapt to new changes and challenges [38]. Resilience and livelihood resilience, in particular, are positively influenced by nature, economy, and human capital [39]. Improving farmers’ livelihood resilience and eradicating poverty is a key policy objective of the EU, but empirical research on perceived livelihood resilience is still limited. The means of eradicating poverty are considered to support and encourage a stable livelihood for farmers. The temporary elimination of permanent poverty is the goal of improving household livelihood resilience to cope with risks and shocks [3]. Today, however, improving livelihood resilience does not necessarily lead to a reduction in poverty [40,41]. Therefore, future policies should be directed towards improving sustainable livelihoods and the perceived social resilience of resettled families at the individual level [40]. Building resilience to ensure well-being requires a careful understanding of resettlers’ thoughts and actions.

Measuring livelihood resilience needs to also consider the individual’s capacities and perceptions of their own livelihood recovery development. Again, respondents are asked to self-assess themselves, using their own internal judgement about their household’s ability to manage livelihood risks [42]. Measuring subjective resilience at the household level allows for an assessment of household resilience and individuals’ perception of the household’s ability to cope with livelihood risks and their own capacities [43].

2.1.2. Gender Differences and Perception of Livelihood Resilience

Hydropower dams will often require involuntary resettlement of households and communities which brings great social and psychological upheaval to individuals and to communities as a whole. Communities and households operate with defined gender roles and responsibilities—these are all affected [44]. The resettler labour force economy has its own vulnerabilities and leads to gender differentiation in the family division of labour, which affects the family’s perception of livelihood resilience [45]. Males and females have different approaches to livelihood recovery and adaptation. Gender roles influence the development and perception of access to and control over resources and livelihood resilience for male and female resettlers. Research points out that although remittances from relocation compensation enable women and families to lead relatively comfortable and secure lives during resettlement, men’s relocation and work lead to increased tasks and responsibilities for women and a decrease in perceptions of resilience [46]. On the other hand, female labour force participation rates are a real challenge [47]. Women are embedded in the social, cultural, economic, political and environmental structures of work employment that shape gender inequalities [48]. Women’s unequal access, control over and ownership of productive resources, such as land, limits their participation in agricultural decision making and increases their dependence on men to achieve their livelihoods [49]. Women may experience greater difficulties in coping with environmental and social stress that affect household stability and well-being [50], with different perceived impacts on livelihoods.

2.2. Description of the PReS Policy

In order to improve the production and living conditions of reservoir resettlers who have made sacrifices and for that matter significant contributions to flood control, power generation, irrigation, water supply and ecology, the State has set up a reservoir maintenance fund, reservoir construction funds and reservoir post-implementation support funds in an effort to solve these problems left behind by reservoir resettlers. Historical issues succeed from the reservoir resettlement mainly associated with weak infrastructure, limited arable area, rural poverty, low educational level, social disconnect of resettlers, etc., [17]. In 2006, an executive meeting of the State Council adopted the revised regulations on “Land acquisition compensation and resettlement for large and medium sized water conservancy and hydropower projects in principle” and the agreement on initiating and improving the PReS regulation for reservoir resettlers. In view of the country’s overall move into a new development paradigm of coordinating urban and rural development, promoting agriculture with industry and bringing rural areas together with cities, and promoting high quality economic and social development in the reservoir and resettlement areas for resettlers, on 17 May 2006, the State Council issued “Opinions on Improving the PReS Policy for Large or Medium-sized Reservoirs” that introduced the PReS policy for sustainable development. This was known as the PReS policy. “Move out, stay stable, can develop, get rich quickly” is a slogan widely used during resettlement and the PReS in China.

The PReS policy plays a significant role in rapidly improving the social, economic, and physical assets of resettlers in the early stage of reservoir resettlement; from the time scale of 15 years of policy implementation, the resettlement policy has an obvious slow release effect on making up for the improvement of natural resources development and human capital [51]. At present, the population of the PReS for reservoir resettlers was about 25 million in China. The PReS is a government initiative yet a resettler-centered policy that determined 20 years of lasting support covering many aspects of resettlers’ livelihood [17]. The policy has some key features, which include: (1) Scope of support: Rural resettlers of large and medium-sized reservoirs. Among them, those relocated before 30 June 2006 are status quo resettlers, and those relocated afterwards are the original relocated population. (2) Support standard: an annual subsidy of 600 yuan for each resettler included in the support scope. (3) Duration of support: 30 June 2006 was the relocation time line, and those relocated before that date will continue to receive support for 20 years; those relocated after that date will continue to receive support for 20 years from the date of completion of relocation. (4) Method of support: a combination of direct support, project support, direct subsidy and project support. Direct support was the direct payment of subsidies to individual resettlers for livelihood assistance; project support was the improvement of outstanding problems in the livelihood of resettlers through construction funds, fund projects, etc. It also includes the arrangement of nonfarm resettlement, infrastructure construction and other resettlement work.

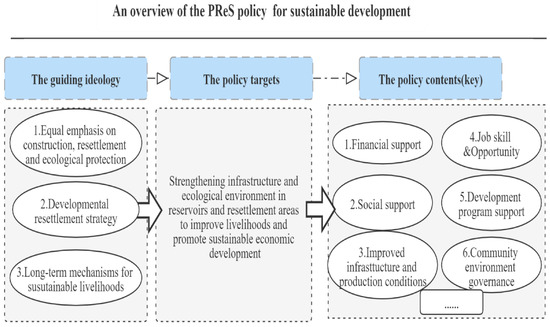

The implement of China’s the PreS policy further supports livelihood recovery and sustainable development of resettled people to some extent. Through the implementation of industrial development projects for resettlers, professionals from all walks of life have been attracted to return to their hometowns to start their own businesses and provide low interest loans, improving the opportunities for resettlers’ collective economy and personal annual income growth through employment and entrepreneurial skills training or education training, resettlers’ livelihoods have been inspired with confidence to become better and personal values have been enhanced through the construction of modern houses, the happiness and perception of access to livelihoods is enhanced, enabling resettlers to gradually adapt to life after relocation, and enhancing the resilience and sustainability of livelihoods. The main overview of the PReS policy for reservoir resettlers is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The main overview of the PReS policy.

2.3. Research Hypothesis

Income stability refers to secure employment, defined as a way to stabilize people’s lives by meeting their basic needs [33,52]. For relocated people, income is a necessary livelihood asset to sustain their lives and adapt to the environment [53,54]. A better financial position for resettlers can give households more opportunities to address or reduce livelihood risks. Studies have shown that financial capital, i.e., the level of household savings and the amount of compensation provided by the government are important factors influencing livelihood resilience [27,55]. Resettlers with better household economic conditions have a greater ability to invest in their own financial capital and greater resilience to various risks and, therefore, a greater perceived level of livelihood resilience. Conversely, the degree of perceived resilience decreases. Given that women have always been treated unequally in terms of economic and social status in remote and poor areas, adding a gender variable to the economic conditions of resettler households means that the distribution of perceived livelihood resilience among resettlers may have new effects or widen existing inequalities. For better off resettlers, the household division of livelihoods and risk perceptions are stronger and less likely to reduce perceived livelihood resilience because of financial livelihood costs. However, for less well-off resettlers, the lack of availability of livelihood capital in the face of unexpected risks such as unemployment or intermittent unemployment due to COVID-19, accidents, etc., may lead to a reduction or even a regression in the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers. In summary, the first hypothesis is proposed that differences in economic conditions will affect the extent to which perceived livelihood resilience is developed in resettled households by gender.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Gender differences in resettlers’ perceived livelihood resilience are inversely related to household economic conditions.

Education provides a firm foundation for development, and it increases the overall productivity of the workforce [56]. Higher education increases the likelihood of obtaining better employment. Research has shown that the level of education is the most important factor in determining the likelihood of finding a job to sustain a livelihood. At the same time, differences in education levels can influence the way resettlers choose to work, leaving them without the skills needed to engage in productive work [57]. Education through culture can give resettlers an identity with certain materiality and economic energy. On this basis, the inclusion of the gender variable further examines whether the level of education of resettler households can have an impact on the gender equality of perceived livelihood resilience. In general, it is assumed that the higher the level of education of a household, the greater its ability to access employment opportunities, market expectations, and social support, and, therefore the higher its perceived livelihood resilience. The lower the level of household education, the lower the livelihoods and adaptive capacity, and the more likely it is that perceived livelihood resilience will be less gendered. Therefore, a second hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Gender differences in the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers are inversely related to household education level.

In developing countries, resettlement accommodation is not only a living place but also a workplace [58]. The perceived level of household homeownership is strongly linked to an individual’s livelihood [33]. Similarly, the perceived state of housing affects individuals’ willingness to maintain and improve their quality of life [59]. Considering the impact of the environmental capacity of the regional population, some resettlers must experience out-relocation. However, it is also this role that drives them gradually closer to the city, accessing factors that may improve their livelihoods as they shift from agriculture to nonagriculture related work. The findings indicate that the stayers are largely disadvantaged in terms of land assets, housing conditions, finance, infrastructure, industrialisation, livelihood strategies, and emotional impact, whereas many distant resettlers are less affected or positively impacted in these aspects [60]. For those who are resettled within their homelands, however, the single means of livelihood, the slim opportunities for development and the low level of education have left most of them in a condition of relative poverty. When gender is further considered, it is possible that the following characteristics are deepened: internal resettlement groups are relatively lacking in terms of household economic conditions, labour force levels, gender perceptions, and educational attitudes, which may pose a clear constraint on women’s perceived livelihood resilience. Thus, a third hypothesis is proposed that gender differences in perceived livelihood resilience will be greater for internal resettlement groups than for external resettlement urban and periurban resettled groups.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Rural resettlers in external resettlement areas have a smaller gender gap in perceived livelihood resilience than in-county resettlers.

Household labour has a critical influence on human capital. CobbDouglas has also shown in the field of economics that an important determinant of the level of development is the level of labour input. It has been suggested that females may face wage discrimination in the labour market [61]. The labour force activities of female resettlers are often considered to be economically irrelevant [62]. The larger the number of resettler households in the labour force, the greater the chance that the household will participate in the labour market and receive greater financial gains. Of course, we do not exclude households with only one or two labour force holders and still have high returns, but these are only a minority. In summary, the share of the household labour force is closely linked to the economic conditions of resettled households. It will influence financial capital through human capital, further affecting resettlers’ perceived livelihood resilience. Therefore, a fourth hypothesis is proposed that differences in the household labour force share may have an impact on the gender equality of resettlers’ livelihood resilience.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Gender differences in resettlers’ perceived livelihood resilience are inversely related to the household labour force share.

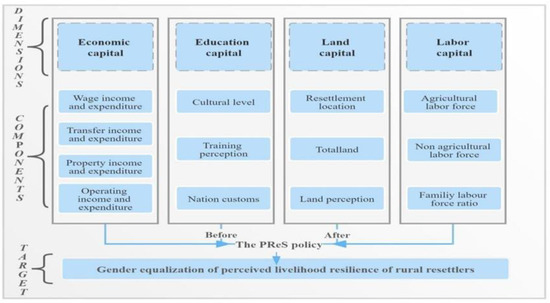

The research framework is shown in Figure 2. The above four interactions and re-search hypotheses are the basis for answering the question of gender equality and livelihood resilience perception. To investigate livelihood resilience perception and gender equality, we took a longitudinal approach by including the PReS (implemented since 2006 to ensure that after relocation and resettlement, reservoir resettlers are able to adapt to life in the resettlement site as soon as possible, restore their livelihoods and achieve quality development) among the variables examined. Specifically, the four hypotheses were used to build a regression model for “before and after the implementation of PReS” to compare the perceived differences in livelihood resilience of the four interaction terms on gender equality. On the one hand, it examines whether females are the main beneficiaries of the PReS policy and whether they contribute to gender equality among economically disadvantaged, less labour intensive, less educated and internally resettled groups. On the other hand, it also provides an assessment of the continuity and value of the PReS policy, which has been in place for 20 years and will cease in 2026. Therefore, the following hypothesis is further developed in this paper:

Hypothesis H5 (H5).

After the implementation of the PReS, the lower the economic conditions of the household, the greater the reduction in the gender inequality gap in perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers.

Hypothesis H6 (H6).

After the implementation of the PReS, the lower the level of household education, the greater the reduction in gender inequality in perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers.

Hypothesis H7 (H7).

After the implementation of the PReS, the difference in perceived gender inequality in livelihoods resilience was greater for resettlers in internal resettlement areas than for resettlers in external resettlement areas.

Hypothesis H8 (H8).

After the implementation of the PReS, the lower the level of labour force, the greater the reduction in perceived gender inequalities in livelihood resilience of resettlers.

Figure 2.

Research framework.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Study Area

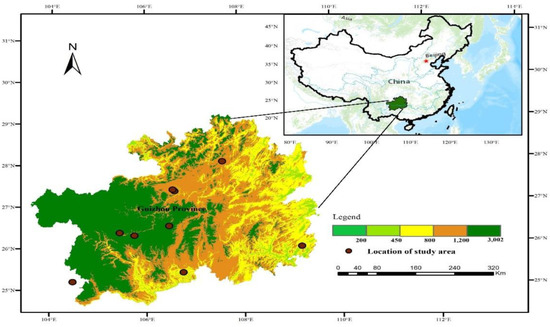

Guizhou Province is located in the mountainous plateau of south western China, 92% of which is mountainous and hilly. It is located on the Yungui Plateau, between 103°36′ and 109°35′ E longitude and 24°37 and 29°13′ N latitude, which is an important part of the Yangtze River Economic Belt. The nine survey areas (Qingzhen City, Weaving County, Qianxi County, Panzhou City, Puding County, Luodian County, Zunyi City, Tianzhu County and Sinan County) are located in the three major watersheds of the Wujiang River, Nanshui Panjiang River and Qingshui River, with a total of 188 reservoirs built and under construction and a total of 702,356 reservoir resettlers having been relocated and resettled. Guizhou is the largest relocation scale and the heaviest relocation task province in China. Therefore, investigating the resettlers within this region is representative and universal. The locations of the areas studied are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The location of the study area (nine districts in Guizhou Province) in China.

According to State Council document No. 471, Guizhou Province has carried out resettlement planning for resettlers based on the carrying capacity of resources and the environment through local resettlement and relocation, centralised resettlement and decentralised resettlement. It also implemented the PReS policy (State Council Document No. 26) in 2006, which provides support according to the approved resettler population with direct subsidy funds of 600 RMB (about USD 94.2) per person per year. A series of livelihood restoration efforts were also carried out, including poverty alleviation, home construction, industrial income generation, employment and entrepreneurship training. Thus, all these strategies are used to guarantee the integration of resettlers into the resettlement areas and support their livelihoods, with the aim of achieving simultaneous development of the reservoir area and the resettlement areas.

3.2. Data Collection

The study used a questionnaire with quantitative measures to collect data from households at the study site, which consisted of five sections. The first section dealt with demographic information about the respondent and basic information about the resettler’s household. The second part was on the household’s land resource status from before and after the land acquisition. The third and fourth sections ask for information on household income and expenditures for the current year, broken down into four areas: wages, business, property, and transfer, to examine the economic conditions of the resettler’s household in a comprehensive manner. Respondents scored their perceived livelihood resilience to identify important indicators of livelihood resilience. Two open-ended questions were included, inviting respondents to provide brief descriptions based on their own circumstances. It is important to note that the livelihood resilience measure is different from the subjective perception measure, but the measure of resettlers’ livelihood resilience should reflect the perceived indicators they are concerned about.

From November 2021 to January 2022, questionnaires were distributed to resettled families in the nine selected regions, with a total of 3700 resettlers responding to the questionnaires. To ensure the sample nature and availability of the questionnaire, the form of one-to-one survey interviews and online answers was adopted, in which questionnaires that had one-to-one invalid filling, did not conform to the actual situation, or had an online answer time of less than 3 min were removed. Finally, 1553 valid questionnaires (41.97%) were included. The information from the resettler section of the questionnaire and interviews is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics (N = 1553).

To further discuss gender differences and changes in the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers before and after the implementation of the PReS policy, a preliminary analysis of the extent and proportion of perceived livelihood resilience of male and female resettlers was conducted prior to modelling, and the results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of the sample distribution of perceived livelihood resilience among male and female resettlers before and after the Post-Relocation Support policy.

Table 2 shows that since the implementation of the PReS policy in 2006, there has been an overall increase in the perceived level of livelihood resilience of resettlers, from less than 25% for both male and female resettlers prior to the implementation of the PReS policy to approximately 45% after the implementation of the PReS policy. Second, with the implementation of the PReS policy, the perceived livelihood resilience of female resettlers increased more rapidly than that of male resettlers, from 23.08% to 45.92%, nearly doubling, whereas that of female resettlers increased from 16.89% to 46.84%, nearly tripling. Thus, in general, perceived livelihood resilience tends to equalise in terms of gender differences among resettlers.

3.3. Research Methods

Before our empirical analysis started, the type of dependent variable and the possible endogeneity of relocation and resettlement should be considered. Avoid the property of missing the best linear deviation. Referring to previous studies [27,63], given a Logit link function, we transform the dependent variable into a linear combination of independent variables.

The dependent variable in this study is perceived livelihood resilience, measured by the perception questions “Are you satisfied with your current household livelihoods?” and “Do you think your standard of living has improved?” Due to the absence of absolute bias in resettlers’ perception of livelihood resilience, the two original questions are again combined here to form a dichotomous variable. The logit model is expressed as follows:

is the probability that the Ith resettler has a better perception of livelihood resilience, is the independent variable, and is the regression coefficient of the independent variable, indicating the degree of influence of the independent variable on the dependent variable, controlling for the other independent variables.

The independent variables in this study include the gender of the resettler, the economic condition of the household, the educational level of the household, the mode of settlement, the labour force share and the interaction term between them. Of these, gender is the key variable in this study. In this paper, the total income of resettled households is first subtracted from the total expenditure and then ranked and finally neutralised as a fixed order variable. The educational level of the household is measured by using the education of the most educated party in the resettled household. The resettlement method transformed centralised resettlement and decentralised resettlement, relocation and local village resettlement into inward resettlement and outward resettlement. The household labour force ratio is measured as a proportion of the total household labour force to the total household size, and those with a labour force ratio of less than 50% are considered to have a low level of household labour force. In addition, because of the different modes of resettlement and regional locations in Guizhou Province, different modes of production and occupation, and the fact that the survey area is also located in an ethnic minority area, several variables were constructed to control for the effects of land sentiment, total agricultural land, number of training sessions and ethnic differences on perceived livelihood resilience. The results of the questionnaire were first imported, and the data were processed using SPSS and Excel. Finally, coding, transformation and analysis were carried out using STATA 17.0.

4. Results

4.1. Regression Analysis

Based on the previous design, this study first tests hypothesis 1–4. Table 3 presents the logit estimates affecting the perceived gender equality of resettlers’ livelihood resilience, including the baseline model and the interaction models (Models 1–4), with the interaction models testing Hypotheses 1–4.

Table 3.

Influence factors and interaction logit model of livelihood resilience perception of gender equality.

From the baseline model, all variables were positively significant, except for the high school level of family education, the number of training, and ethnicity variables. The perceived livelihood resilience of male resettlers was 1.31 times (e0.272) higher than that of female resettlers. This indicates that, controlling for other variables, there is gender inequality in perceived livelihood resilience during the overall time period since the resettlers were relocated and resettled.

Before the implementation of China’s 2006 PReS policy, perceived livelihood resilience increased by a factor of nearly 1.9 after implementation (e1.063−1). At the same time, we found that the difference in relocation method also had a significant impact on the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers, with external resettlement groups (those who were within the inundation line due to reservoir construction and relocated to live outside their original location in urban or peri-urban settlements) having 1.8 times higher perceived livelihood resilience than internal resettlement groups (e1.042−1), which is consistent with the scholarly findings [51,64]. However, a novel finding of our research is that although resettlers’ household conditions positively contributed to perceived livelihood resilience, the degree of contribution was modest in terms of coefficients. That is, resettlers’ perceptions of livelihood resilience increased by only 11% (e0.097) for each step up the scale.

In terms of the baseline model, it has been shown that household economic conditions have a significant positive effect on perceived livelihood resilience. Based on this, this study uses Model 1 to test whether this positive effect differs between resettlers depending on gender. Model 1 shows that the coefficient on the interaction term between gender and household conditions is not significant, which could be interpreted as each level of increase in household economic condition has approximately the same effect on the perceived livelihood resilience of male and female resettlers, increasing by a factor of 1.12 (e0.110). Therefore, the hypothesis of Model 1 was not supported.

There is also an effect on the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers in terms of household educational attainment, but the extent of the effect becomes less significant as the level of education increases. The base model shows that the perceived livelihood resilience increases by a factor of 0.3 (e0.259 − 1) for the group with a primary school education in the household relative to the group with an incomplete primary school education and that is illiterate; the PReSence of a member of the household with a secondary school education increases the perceived livelihood resilience by a factor of 0.2 (e0.217 − 1), whereas the PReS of a member of the household with a high school education is not significant. We also find that the ethnicity variable is not significant, but this does not mean that there are no differences in livelihood resilience between ethnic groups and gender, which could be due to several reasons, including sampling bias, as only 5% of the sample are ethnic minorities, and the uneven distribution of ethnic minorities among resettled households.

Further exploring the hypothesis of differences between household educational attainment and resettler gender, Model 2 first shows that males gain 1.46 times (e0.381) more perceived livelihood resilience than females in resettled households with incomplete primary schooling and illiteracy. It is evident from the interaction term that the difference in livelihood resilience between genders widens as household education increases, as evidenced by a perceived livelihood resilience ratio between males and females of 1.74 and 1.87 (e0.828−0.272, e0.828−0.201) for households with primary and lower secondary education; however, when household education reaches high school and beyond, the livelihood resilience ratio falls again to 1.49 (e0.828−0.429). This does not contradict common sense, as most of the rural resettlers selected for the survey belong to the older generation of reservoir resettlers, whose reported literacy and education are at the primary and junior high school levels, and who do not report high school education, leading to a downwards trend. Therefore, the hypothesis of Model 2 was partially supported.

Second, the hypothesis of the difference between resettlement mode and resettler gender is explored. Model 3 shows a significant interaction term coefficient, indicating that the difference in resettlement mode affects gender inequality in the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers. In terms of performance, male resettlers in internal resettlement perceive livelihood resilience to be 4.53 times greater than females (e1.511); in contrast, in the external resettlement group, men’s perception of livelihood resilience is almost equal to that of women (1 − e0.833−0.794). The gender inequality gap in livelihood resilience exhibited in the baseline model can, therefore, be largely attributed to gender inequalities in perceived livelihood resilience arising from differences in current settlement patterns. Hypothesis 3 is confirmed.

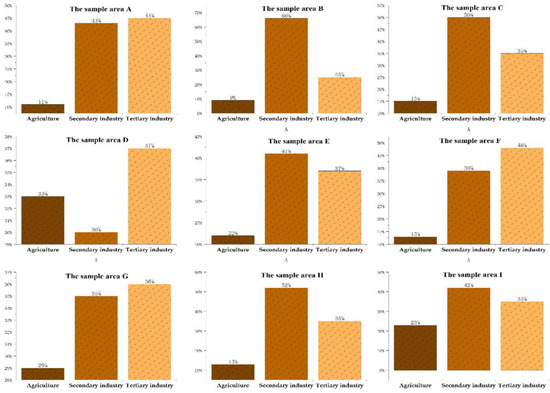

Next, we focus on the hypothesis of gender differences in perceived livelihood resilience inequalities in the labour force of resettled households. Labour force and income structure are closely related. As we can see from the graph of the structure of income from employment in the nine sample regions (Figure 4), current resettlers sustain their livelihoods mainly in the secondary and tertiary sectors. Land-based agricultural production, on the other hand, is maintained by only 11–33% of resettlers. The resettled labour force is gradually moving from agricultural into nonagricultural sectors such as manufacturing and business [59]. In our research interviews, we also found that resettlers in the labour force tend to engage in agricultural activities only after they are engaged in secondary and tertiary industries, i.e., only when they are not working in secondary and tertiary industries do resettlers take care of their land, but this does not mean that land is not important for resettlers’ livelihoods. Land is fundamental to resettlers’ survival and development and is an important asset for obtaining livelihoods.

Figure 4.

Income structure of the sample area. (A to I are the nine areas selected by the research team respectively).

Finally, we consider gender differences in the labour force in the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers. The baseline regression model shows that the household labour force share has a positive effect on perceptions of livelihood resilience. For each one rank increase in labour force share, the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers increases by 22.9% (e0.206). The regression of the interaction term between gender and household labour force share showed a negatively significant coefficient; thus, the difference between men and women in perceived livelihood resilience decreased as the degree of household labour force share increased. Thus, the hypothesis of Model 4 was confirmed.

4.2. Further Discussion

The PReS policy for reservoir resettlers in China was implemented in 2006 and will end in 2026, lasting 20 years. To consider the continuity value of the PReS policy, this study further included four interaction terms in the regression models before and after the implementation of the PReS policy to see how the effects of resettlers’ household economic conditions, education level, settlement mode and labour force on perceived livelihood resilience changed across gender before and after the implementation of the PreS (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparative model of livelihood resilience perception before and after PReS policy implementation.

We first examine Models 5 and 6, which measure the effect of gender differences in household economic conditions on resettlers’ perceived livelihood resilience before and after the implementation of the PReS policy, respectively. Before the implementation of the PReS policy, the perceived livelihood resilience of men in economically disadvantaged resettled households was 1.43 times higher than that of women (e0.360), but after the implementation of the policy, the ratio of perception of male to female resettlers was 0.87 (e−0.135). Again, as the coefficient on Model 6 is not significant, we can assume that the implementation of the PReS policy reduced the gender inequality difference in perceived livelihood resilience among economically disadvantaged resettler households. In terms of the interaction term, the coefficients are not significant before or after the implementation of the PReS policy, which suggests that the gender differences in perceived livelihood resilience among resettlers tend to equalize with respect to the economic conditions of households before and after the implementation of the PReS policy. In other words, as the PReS policy continues to be implemented, household economic conditions are not a major factor in the gender differences in the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers. This is also consistent with the findings of Model 1, so hypothesis 5 did not pass the test.

Now proceeding to Models 7 and 8, which show the effect of household education on perceived livelihood resilience by gender before and after the implementation of the PReS policy, respectively. Before the implementation of the PReS policy, the perceived livelihood resilience of male resettlers who had not completed primary school and were illiterate was 1.49 times higher than that of female resettlers (e0.397); after the implementation of the policy, the difference was 1.47 times higher (e0.384), suggesting that although the PReS policy had been implemented, it did not continue, indicating that although the gap narrowed after PReS implementation, the degree of narrowing is not significant. This suggests that the gender inequality gap in perceived livelihood resilience among resettlement households with little or no literacy has not improved with the PReS policy. Among resettlement households with primary and lower secondary levels of education, the perceived livelihood resilience of males was 1.33 and 1.35 times higher than that of female resettlers before the expansion (e0.384−0.099, e0.384−0.084) and 1.23 and 0.78 times higher than that of female resettlers after the expansion (e0.384−0.181, e0.384−0.635). This contributes to the gender equalization of resettlers’ perceptions of livelihood resilience. The coefficients are not significant for household education at the level of high school and above, which is consistent with the reasons explained above. Hypothesis 6 passed the partial test.

Second, in Models 9 and 10, which show the effect of relocation and resettlement methods on perceived livelihood resilience by gender before and after the implementation of the PReS policy, respectively. The perceived livelihood resilience of men in internal resettlement was 1.67 times higher (e0.513) than that of women before the implementation of the PReS policy and 1.5 times higher (e0.415) after the implementation of the PReS policy. Although the proportional change is small, it suggests that the implementation of the PReS policy has had a positive effect on reducing the perceived gender equality in livelihood resilience among the internal resettlement group. The perceived livelihood resilience of male resettlers was 1.36 times higher than that of female resettlers before the PReS policy was implemented (e0.513−0.203) and became 1.1 times higher after the policy was implemented (e0.513−0.421). Thus, the gender difference in the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers narrowed for both internal and external resettlement, but in terms of magnitude, the external resettlement group experienced greater gender equality in perceived livelihood resilience. Hypothesis 7 was confirmed.

Finally, Models 10 and 11 show that the impact of labour force participation on perceived livelihood resilience between genders before and after the implementation of the PReS policy. Prior to the implementation of the policy, the perceived livelihood resilience of male resettlers was 1.5 times higher (e0.415) than that of females in the group of resettlers with higher levels of household labour force, and this gap was reduced to 1.24 times (e0.221) after the implementation of the policy. Thus, the implementation of the PReS policy has contributed positively to the gender equalization of perceived livelihood resilience among households with higher levels of labour force among resettlers. In contrast, among resettled households with lower levels of labour force, the perceived livelihood resilience of men before the implementation of the policy was 82% of that of female resettlers (e0.415−1.19). After the implementation of PReS, men’s perception was 30% less than that of female resettlers (1 − e0.221−0.580). Thus, the implementation of the PReS policy reduced gender inequalities in perceived livelihood resilience among resettler households, both among those with higher and lower labour force levels, but resettlement households with lower labour force levels had a greater impact on the gender equalization of perceived livelihood resilience after the implementation of the policy, and Hypothesis 8 was confirmed.

To summarize the above analysis, the key variables in this study are summarized before and after the implementation of the PReS policy in Table 5, which provides a clear picture of the contribution of gender equality to the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers.

Table 5.

Contribution ratio of perceived livelihood resilience before and after implementation of PReS policy.

5. Discussion

Against the background of large-scale displacement and resettlement, a survey of rural reservoir resettlers’ livelihood in nine regions of Guizhou Province, China, examines the factors that influence the gendered perceptions of resettlers’ livelihood resilience and how the benefits of the PReS policy are distributed by gender, leading to gendered perceptions of livelihood resilience. The findings provide empirical evidence that livelihood recovery and development among resettlers varies by gender, as well as the institutional and impact evaluations of the upcoming PReS for resettlers.

First, the empirical results show that household economic conditions have a significant impact on the perceived level of resettler livelihood resilience. Male and female resettlers get different resources and benefit sharing in hydropower projects [44]. However, there are no obvious gender differences in this effect over the entire relocation settlement cycle. The distribution of perceived livelihood resilience between the genders of resettlers does not change dramatically with the economic condition of the household. The effective avoidance of risks and the material income brought by the construction of production projects improve the overall economic capital of resettled families [15]. In the regression model incorporating the PReS policy, the results show that the implementation of PReS reduces the gender gap in perceived livelihood resilience for both better- and worse-off households and that the gender gap in perceived livelihood resilience tends to equalize between male and female resettlers after the implementation of PReS, regardless of household economic conditions. Specifically, household economic status has gradually ceased to be a mechanism for the transition from gender differences in resettlers’ perceived livelihood resilience to inequality. The PReS policy promotes the relatively rapid improvement of physical, social and financial assets by resettlers, reverses the shrinking trend of livelihood capital, and promotes the balance of livelihood capital [17].

Second, previous research has focused solely on the educational attainment of individual resettlers, neglecting the impact of family education as a whole on individuals and between genders [59]. The results show that increased levels of household education can lead to an increase in the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers. However, there are significant gender differences in this resilience across households. Throughout the resettlement cycle, male resettlers perception of livelihood resilience was significantly higher than female resettlers when their household education was at the primary and lower secondary levels. However, this gender inequality in perceived resilience begins to disappear as household education rises to the high school level and higher. This result may be related to the small number of resettlers with high school education or higher at the time of the survey sample, but it is still largely caused by the low level of reported education among the older generations of resettlers. The difference in perceived gender inequality in livelihood resilience for resettled households with little to no literacy before and after the implementation of the PReS policy did not improve significantly with the implementation of the policy. For resettled households with primary and lower secondary education, the implementation of the PReS policy contributed to the perceived livelihood resilience of female resettlers, resulting in decreasing gender distribution of resettlers’ perceived livelihood resilience. Regarding whether high school education or higher results in gender inequalities in resettlers’ perceptions of livelihood resilience, expanding the proportion of this group investigated among old and new reservoir resettlers is also a direction for further research in the future.

Third, the extent to which differences in resettlement mode affect resettlers’ perceived livelihood resilience is evident. Resettlers in the rural internal resettlement group had significantly lower livelihood resilience perceptions than those in the external resettlement group. Livelihood resilience varies between internal and external resettlement groups; scattered resettlement groups were more negatively affected [63]. In our research, the results show that the perceived livelihood resilience of male resettlers in the internal resettlement group was significantly higher than that of female resettlers throughout the relocation and resettlement cycle, whereas in the external resettlement areas, the perceptions of males and females were almost equal. Longitudinally, the gender equality difference in the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers narrowed after the implementation of PReS in both internal and external resettlement, but in terms of magnitude as well as numerical magnitude, the external resettlement group contributed more to the gender equalization of perceived livelihood resilience.

Fourth, the results show that the level of household labour is also a prominent contributor to the perceived gendered equalization of resettlers’ livelihood resilience. With the growth of manufacturing and various enterprises, resettlers have also gradually moved towards urbanization and transitioned from agricultural work to employment in secondary and tertiary industries. Resettlement brings the effect of losing labor force to resettlers in agricultural production, and reduces household labor input [65]. The income structure map for the nine sample regions of the survey confirms this finding, but regardless of labour and income structure, the interaction between gender and household labour force shows that gender differences in resettlers’ perceived livelihood resilience narrow significantly as the degree of household labour force increases. However, for households with higher levels of labour force, this perceived gender equalization played a greater role with the implementation of PReS. Therefore, the full release of the household workforce and higher levels of mechanized production can help to build a more equal perception of livelihood resilience and promote the sustainable development of resettlers [3].

The results make a helpful contribution to understanding the experiences of resettlers of rural reservoirs, but the study has limitations. First, this paper is based on a quantitative survey, and although several qualitative questions were addressed in the questionnaire, the questions were not strongly correlated with resettler gender differences and, therefore, may need to be supplemented with a conventional survey that can better reflect resettler perceptions of livelihood resilience between genders. Second, in future research, different levels of resettler groups should be more carefully delineated to better assess the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers, and more sophisticated data analysis methods could be conducted to more clearly elucidate the relationship between the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers after relocation and resettlement and gender. Finally, indicators analyzing the perceived livelihood resilience of resettlers in relation to gender equality may be inadequate or fail to describe some important variables, and therefore, more indicators that potentially or indirectly affect differences in perceived livelihood resilience due to the gender of resettlers should be included.

6. Conclusions

In developing countries, the construction of dams often changes the livelihoods of villagers in their original settlement, and their relocation and resettlement disrupt normal livelihood activities. This study empirically examines the equality of resettlers’ perceptions of livelihood resilience by gender using Guizhou Province, China, as an example. We aim to measure whether current resettlers’ perceptions of livelihood resilience reflect different effects along with gender difference. The results indicate that male resettlers have different perceptions of livelihood resilience than female resettlers. Further analysis of the data suggests that the PReS policy can lead to a gender equalizing effect on perceived livelihood resilience, with an overall state of sustainable livelihood development. However, the contribution to gendered perceptions of livelihood resilience among resettlers is because the variety of livelihood opportunities presented by the PReS policy changes the structure of perceived resilience between male and female resettlers as a whole.

First, resettlers with higher levels of education received more opportunities for strengthening livelihood resilience through the PReS implementation, thus contributing more to the gendered perception of livelihood resilience. Therefore, it is necessary that, with the empowerment resettlers as the center, women’s federations, trade unions and other organizations are connected to conduct vocational education training and post training, and use professional skills such as social work to influence and change the psychological cognition of resettlers, so that the perception of livelihood resilience tends to gender equality.

Second, in the case of external resettlement groups, their perceived livelihood resilience increases significantly after moving to urban or peri-urban areas, improving the disadvantageous position of rural women in this group and reducing the difference in perceived livelihood resilience between female and male resettlers. We suggest that the relevant departments should adopt a reasonable resettlement method, combined with the current situation of resettled livelihood, with the goal of promoting a sustainable resettler livelihood for a reasonable resettlement.

Finally, the degree of household labour, as urban–rural integration and urbanization accelerate, also brings about different perceptions of livelihood resilience in terms of the structure of employment and income differences, thus affecting the gender equality of resettlers. Promoting the transformation of grassroots communities, accelerating the integration of the three industries and moving from ‘government-led’ to ‘resettler self-governance’ is crucial to promoting gender equality in the perception of resettlers’ livelihood resilience. This is essential for promoting gender equality in the perceived resilience of resettlers’ livelihoods, which is also a necessary path for the revitalisation of China’s rural development.

These findings may be more applicable to rural areas in China and elsewhere. However, they should also be instructive for more developed areas. Based on the extensive discussion of farmers’ livelihood resilience, further efforts should be made to understand gender differences within resettler subjects and to consider how to respond to shocks and interventions with different livelihood resilience perspectives for the resettlement and the PReS of reservoir resettlers.

Author Contributions

Supervision, writing—reviewing and editing, funding acquisition, G.S.; conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; investigation, software, validation, X.M.; investigation, supervision, D.Y.; investigation, project administration, H.Z.; resources, supervision, Y.X. and Y.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research Project of the National Foundation of Social Science of China (Fund No. 21&ZD 183), Community Governance and Post-relocation Support in Cross District Resettlement.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yi, F.; Deng, D.; Zhang, Y. Collaboration of top-down and bottom-up approaches in the post-disaster housing reconstruction: Evaluating the cases in Yushu Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of China from resilience perspective. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, E.; Andrei, S.; Huq, S.; Flint, L. Resilience synergies in the post-2015 development agenda. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 1024–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Deng, Q.; Zhou, Y. Livelihood resilience and the generative mechanism of rural households out of poverty: An empirical analysis from Lankao County, Henan Province, China. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 93, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, A. Measuring livelihood resilience: The Household Livelihood Resilience Approach (HLRA). World Dev. 2018, 107, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, T.E.; Shi, G.; Zaman, M.; Garcia-Downing, C. Improving Post-Relocation Support for People Resettled by Infrastructure Development INTRODUCTION. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2021, 39, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Owen, J.R.; Kemp, D.; Shi, G. An applied framework for assessing the relative deprivation of dam-affected communities. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M. The risks and reconstruction model for resettling displaced populations. World Dev. 1997, 25, 1569–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M.M. Understanding and preventing impoverishment from displacement—Reflections on the state of knowledge. In Understanding Impoverishment: The Consequences of Development-Induced Displacement, 1st ed.; International Conference on Development-Induced Displacement; McDowell, C., Ed.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 1996; Volume 2, pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, H.M. The impoverishment risk model and its use as a planning tool. In Development Projects and Impoverishment Risks: Resettling Project-Affected People in India; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Habich-Sobiegalla, S.; Rousseau, J. Responsibility to choose: Governmentality in China’s participatory dam resettlement processes. World Dev. 2020, 135, 105090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M.M. Risks, safeguards and reconstruction: A model for population displacement and resettlement. Econ. Political Wkly. 2000, 35, 3659–3678. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.; Sliuzas, R.; Mathur, N. The risk of impoverishment in urban development-induced displacement and resettlement in Ahmedabad. Environ. Urban 2015, 27, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J. A ‘capability approach’ to understanding loses arising out of the compulsory acquisition of land in India. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rongjing, W.; Bin, W. A brief discussion of new-type urbanization theory for China. Public Policy Admin. 2014, 2, 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Heming, L.; Waley, P.; Rees, P. Reservoir resettlement in China: Past experience and the Three Gorges Dam. Geogr. J. 2001, 167, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudder, T.; Colson, E. From welfare to development: A conceptual framework for the analysis of dislocated people. In Involuntary Migration and Resettlement; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 267–287. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Shi, G.; Dong, Y. Effects of the Post-Relocation Support Policy on Livelihood Capital of the Reservoir Resettlers and Its Implications-A Study in Wujiang Sub-Stream of Yangtze River of China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.; Nair, R.; Guoqing, S. Resettlement in Asian Countries: Legislation, Administration and Struggles for Rights; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Owen, J.R.; Shi, G. Land for equity? A benefit distribution model for mining-induced displacement and resettlement. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3410–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusset, X.; Teller, C. Supply chain capabilities, risks, and resilience. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 184, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, A.; Graber, R.; Jones, L.; Conway, D. Subjective measures of climate resilience: What is the added value for policy and programming? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 46, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, A.; Slijper, T.; de Mey, Y.; Meuwissen, M.P.M.; Poortvliet, P.M.; Rommel, J.; Hansson, H.; Vigani, M.; Soriano, B.; Wauters, E.; et al. Resilience capacities as perceived by European farmers. Agric. Syst. 2021, 193, 103224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, M.; Pahl-Wostl, C. Mechanisms of Resilience in Common-pool Resource Management Systems: An Agent-based Model of Water Use in a River Basin. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Understanding China’s dam-induced resettlement under the institutionalised governance process of policy coevolution. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 283, 111968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Yan, D. Interpretation of Resettlement Long-term Compensation under the “Field -Habitus” Perspective “Field—Habitual” perspective of hydropower migrants long-term compensation resettlement. Nanjing J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2011, 58–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Souksavath, B.; Maekawa, M. The livelihood reconstruction of resettlers from the Nam Ngum 1 hydropower project in Laos. Int. J. Water Resour. D 2013, 29, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunardi; Gunawan, B.; Manatunge, J.; Pratiwi, F.D. Livelihood status of resettlers affected by the Saguling Dam project, 25 years after inundation. Int. J. Water Resour. D 2013, 29, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kura, Y.; Joffre, O.; Laplante, B.; Sengvilaykham, B. Coping with resettlement: A livelihood adaptation analysis in the Mekong River basin. Land Use Policy 2017, 60, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatwangire, A.; Holden, S.T. Land Tenure Reforms, Land Market Participation and the Farm Size—Productivity Relationship in Uganda. In Land Tenure Reform in Asia and Africa: Assessing Impacts on Poverty and Natural Resource Management; Holden, S.T., Otsuka, K., Deininger, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 187–210. [Google Scholar]

- Adelman, S.; Peterman, A. Resettlement and Gender Dimensions of Land Rights in Post-Conflict Northern Uganda. World Dev. 2014, 64, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilt, B.; Braun, Y.; He, D. Social impacts of large dam projects: A comparison of international case studies and implications for best practice. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, S249–S257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Han, Z.; Shi, G. A Study on the Protection of Women’s Land Rights and Interests in The Marriage of Hydropower Migrants: A Case Study of Hongjiadu Hydropower Station. In Proceedings of the 2011 Annual Conference of Chinese Sociology “Analysis of Gender Research Methodology”, Nanchang, China, 24 July 2011. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Sina, D.; Chang-Richards, A.Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R. A conceptual framework for measuring livelihood resilience: Relocation experience from Aceh, Indonesia. World Dev. 2019, 117, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C.; Riba, A.; Wilson, D. Impacts of resilience interventions—Evidence from a quasi-experimental assessment in Niger. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 43, 101390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, D.; Sutherland, M.; Ifejika Speranza, C. The role of tenure documents for livelihood resilience in Trinidad and Tobago. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, T.; Lewis, D.; Wrathall, D.; Bronen, R.; Cradock-Henry, N.; Huq, S.; Lawless, C.; Nawrotzki, R.; Prasad, V.; Rahman, M.A.; et al. Livelihood resilience in the face of climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifejika Speranza, C.; Wiesmann, U.; Rist, S. An indicator framework for assessing livelihood resilience in the context of social–ecological dynamics. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamwanza, A.M. Livelihood resilience and adaptive capacity: A critical conceptual review. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2012, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Pramanik, S.; Mamidanna, S.; Whitbread, A. Climate risk, vulnerability and resilience: Supporting livelihood of smallholders in semiarid India. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebboth, M.G.L.; Conway, D.; Adger, W.N. Mobility endowment and entitlements mediate resilience in rural livelihood systems. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 54, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthopoulou, T.; Kaberis, N.; Petrou, M. Aspects and experiences of crisis in rural Greece. Narratives of rural resilience. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 52, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L. Resilience isn’t the same for all: Comparing subjective and objective approaches to resilience measurement. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2019, 10, e552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Tanner, T. ‘Subjective resilience’: Using perceptions to quantify household resilience to climate extremes and disasters. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2017, 17, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M. Balancing the Scales–Using Gender Impact Assessment in Hydropower Development. Oxfam Australia, Melbourne. 2013. Available online: http://resources.oxfam.org.au/pages/view.php (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Francis, E. Gender, Migration and Multiple Livelihoods: Cases from Eastern and Southern Africa. J. Dev. Stud. 2002, 38, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haas, H.; van Rooij, A. Migration as Emancipation? The Impact of Internal and International Migration on the Position of Women Left Behind in Rural Morocco. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2010, 38, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaad, R.; Hendy, R.; Lassassi, M.; Yassin, S. Explaining the MENA paradox: Rising educational attainment yet stagnant female labor force participation. Demogr. Res. 2020, 43, 817–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeratunge, N.; Snyder, K.A.; Sze, C.P. Gleaner, fisher, trader, processor: Understanding gendered employment in fisheries and aquaculture. Fish Fish. 2010, 11, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cely-Santos, M.; Hernández-Manrique, O.L. Fighting change: Interactive pressures, gender, and livelihood transformations in a contested region of the Colombian Caribbean. Geoforum 2021, 125, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeles, L.C.; Hill, K. The gender dimension of the agrarian transition: Women, men and livelihood diversification in two peri-urban farming communities in the Philippines. Gend. Place Cult. 2009, 16, 609–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gou, J.; Tian, P. Unintended consequences and changes of the late supporting reservior resettlement. J. Hohai Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2022, 24, 77–82. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Marschke, M.J.; Berkes, F. Exploring strategies that build livelihood resilience: A case from Cambodia. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmsen, B.; Webber, M. What can we learn from the practice of development-forced displacement and resettlement for organised resettlements in response to climate change? Geoforum 2015, 58, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, T.E. Creating poverty: The flawed economic logic of the World Bank’s revised involuntary resettlement policy. Forced Migr. Rev. 2002, 12, 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, T.M.H.; Schreinemachers, P.; Berger, T. Hydropower development in Vietnam: Involuntary resettlement and factors enabling rehabilitation. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraresi, M. Immigrants, social transfers for education, and spatial interactions. J. Urban Econ. 2021, 103423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budría, S.; Martínez-de-Ibarreta, C. Education and skill mismatches among immigrants: The impact of host language proficiency. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2021, 84, 102145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I. An overview of post-disaster permanent housing reconstruction in developing countries. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2011, 2, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, W.M.; Stegman, M.A. The effects of homeownership: On the self-esteem, perceived control and life satisfaction of low-income people. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1994, 60, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, G.; Yan, D. What about the “Stayers”? Examining China’s Resettlement Induced by Large Reservoir Projects. Land 2021, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Song, S. Rural–urban migration and wage determination: The case of Tianjin, China. China Econ. Rev. 2006, 17, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adserà, A.; Ferrer, A. Occupational skills and labour market progression of married immigrant women in Canada. Labour Econ. 2016, 39, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Xu, J. Effects of disaster-related resettlement on the livelihood resilience of rural households in China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 49, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Lyu, Q.; Shangguan, Z.; Jiang, T. Facing Climate Change: What Drives Internal Migration Decisions in the Karst Rocky Regions of Southwest China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Jiang, Y. Heterogeneous effects of rural–urban migration and migrant earnings on land efficiency: Empirical evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).