1. Introduction

Since the 1990s there has been an accelerated change in the diets and lifestyles of populations around the world. This evolution, designated as a “nutritional transition”, is mainly linked to the industrialisation pressure, urbanisation, and growing globalisation of traditional food systems, sometimes with harmful consequences for the health and nutritional status of populations. Developing countries and countries with economies in transition are particularly affected [

1,

2,

3].

Modern food systems and diets are characterised by the consumption of foods with high energy density, generally rich in saturated fat, salt, and sugar, and hardly containing unrefined carbohydrates [

2]. At the same time, the urban lifestyle leads to a decrease in metabolic energy expenditure associated with a sedentary lifestyle. Indeed, city dwellers using motorised transport do not devote themselves to physical activities and have leisure activities that involve low energy expenditure. As a result of this concomitant change in diet and lifestyle, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are increasingly becoming important causes of death, both in developing countries and in countries with economies in transition [

1]. Fifty years ago, the majority of worldwide deaths were caused by infectious diseases. In 2013, two out of three worldwide deaths were caused by NCDs and the number of deaths from these diseases increased by 15% between 2010 and 2020. However, most of this increase was localized in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Africa [

4].

Meat is a valuable source of macro- and micronutrients, including protein, vitamins, iron, and zinc. Its consumption is very beneficial for health. However, the increased and imbalanced consumption of animal source products has harmful effects on the health of populations. Indeed, the high availability of meat and the decrease in its cost sometimes lead to the excessive consumption of this product, leading to a high fat intake which is harmful to the health [

1]. In addition, meat is known for its high concentration of uric acid and may be a contributing factor to obesity, cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes, etc. Thus, in recent years, several epidemiological studies have demonstrated an association between the high consumption of meat (red/processed) and the increased risk of obesity and NCDs [

5]. The study by Wolk [

6] showed an increased risk of the main NCDs (diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, etc.) due to the high consumption of red meat (100 g/day) and processed meat (50 g/day). Moreover, just one additional meal taken away from home per week is associated with a 6% increased risk of pre-hypertension [

7].

In Senegal, the demographic pressure and increasing urbanisation have strongly contributed to out-of-home consumption, especially in popular neighbourhoods, and significantly to the change in the eating habits of populations [

8]. Indeed, for households living in difficult and precarious conditions, it is cheaper to buy a meal for the group than prepare it at home [

9]. In the out-of-home catering sector, the development of dairy bars, canteens, fast-food restaurants, and dibiteries perfectly illustrate the nutritional transition of Senegalese populations [

10]. Dibiteries are informal catering outlets. They are mostly owned by citizens from Senegal, Mauritania, and Niger and mainly specialise in braised meat from small ruminants (especially sheep) and occasionally chicken over a wood or charcoal fire [

11,

12,

13]. The sheep meat prepared in these dibiteries is particularly appreciated and its consumption is very anchored in the eating habits of the Senegalese populations. However, knowledge and perceptions as well as the extent of NCD risks are poorly known from these populations. In fact, in addition to inequalities in access to care, three-quarters of Dakar residents with hypertension are unaware of being sick and the risk of mortality linked to the non-treatment and ignorance of NCDs in Dakar is today very high [

14,

15].

Previous studies on food environments and health status have highlighted the importance of identifying the factors that influence eating behaviours and food safety, especially in disadvantaged areas, as an important step in ensuring that interventions and policy changes will be informed by local evidence [

16,

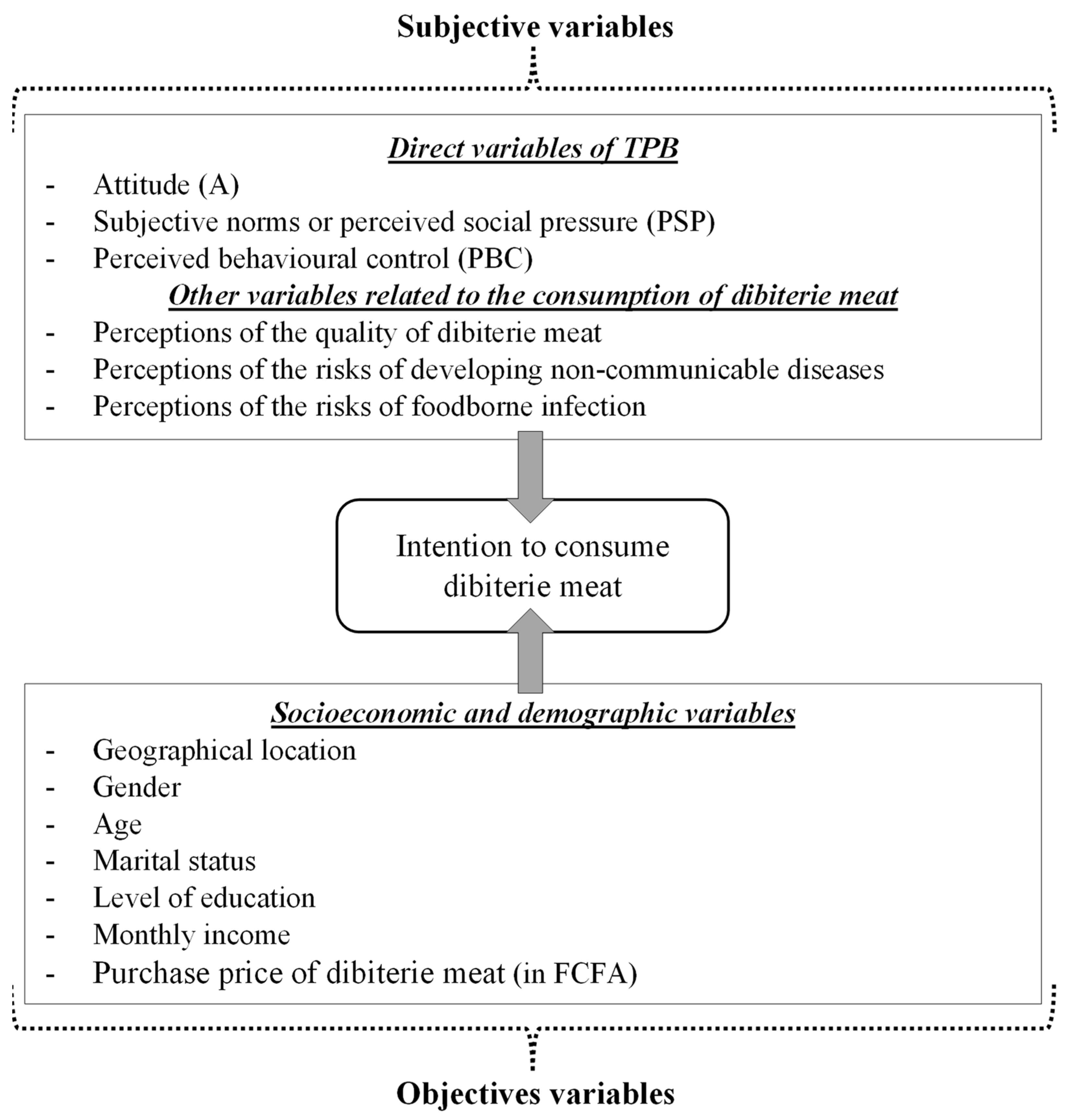

17]. An analysis of the association between the motivation to consume dibiterie meat and the risks of developing NCDs in this population is essential for the design and implementation of behavioural interventions aimed at preventing and controlling NCDs in the context of high meat consumption. To the best of our knowledge, no study in Senegal has yet addressed this issue. This study, therefore, aims to (i) examine the socio-demographic characteristics and population’s preferences of dibiterie meat consumption; (ii) determine socioeconomic and demographic factors related to dibiterie meat consumption; (iii) analyse determinants of the intention to consume dibiterie meat in relation to the risks of NCD development.

4. Discussion

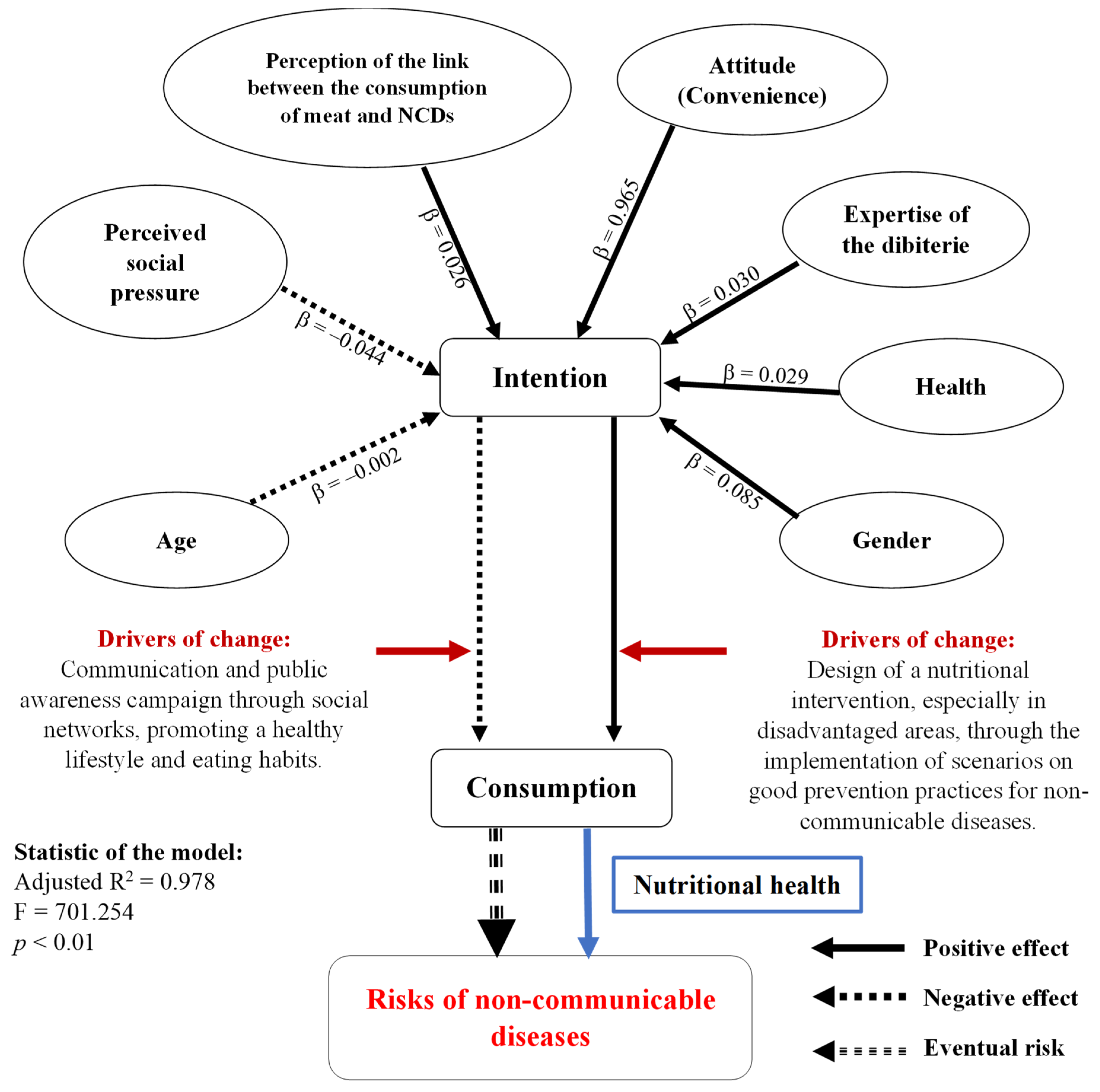

The present study showed that half of the people consume dibiteries meat. Their frequency of consumption was mostly once a month and the quantities varied from 1.5 to 6 Kg according to whether the meat was purchased and consumed at home. “Well-cooked” meat was the preferred mode of cooking by consumers. The identification of the determinants of the dibiterie meat consumption showed among the socio-demographic and economic factors that geographical location, gender, age, monthly income, and family size significantly determined the dibiteries meat consumption. In addition, attitude (convenience), perceived social pressure, the expertise of the dibiterie, health, perception of the link between meat consumption and NCDs, gender, and age of consumers were the determinants of the intention to consume the dibiterie meat in households in the Dakar region.

Socio-demographic and economic determinants of the consumption of dibiterie meat have shown the significant influence of geographic location, gender, age, family size, and monthly income on the consumption of dibiterie meat. However, among these variables, income appeared to be the most discriminating factor, due to its high coefficient in the model.

The positive influence of geographic location on the consumption of dibiterie meat means that households living in Dakar tend to consume more dibiterie meat than those in the suburbs. The purchasing power of the populations of Dakar, which is higher than that of the rest of the country, explains this difference. According to Orou Seko et al. [

13], it constitutes a factor of attractiveness, installation, and concentration of the production and marketing workshops such as dibiteries in popular neighbourhoods of this department. In the practice of dibiterie meat consumption, women significantly eat more than men. The organisation of meals in households in Dakar may explain this result. Indeed, evening meals are rarely taken with the family. Thus, to ensure the evening’s needs in the household, women tend to turn to collective catering such as dibiteries and fast-food restaurants. These dibiteries have operating hours that coincide perfectly with the evening meals of the population living especially in popular neighbourhoods [

8,

13]. The study by Orou Seko et al. [

39] on the out-of-home consumption of dibiterie meat had instead shown that women (21%) were poorly represented compared to men (79%). This confirms the idea that few women consume dibiterie meat in the outlets. The act of purchase they make is in most cases for family consumption rather than for individuals.

In this study, the factor of age above 60 years negatively influences the consumption of dibiterie meat in households in Dakar. In other words, the older people get, the less they eat dibiterie meat. Indeed, the elderly must pay more attention to their lifestyle by adopting healthier eating behaviours towards the risks of NCDs. For example, the elderly must pay attention to their health by reducing their consumption of animal fats by eating more fish [

40].

In Dakar, Mankor [

41] revealed that the level of income has a positive influence on the amount spent monthly by households on the purchase of meat in the sense that the higher the level of income, the more money is spent monthly on the purchase of fresh meat. This result is in line with the economic theory linking increased income and the consumption of luxury animal products, which is not verified for processed products (braised meat). Our results have shown that the income “less than 75 Euros” positively influences the consumption of dibiterie meat; these are individuals with an income lower than the minimum wage in Senegal, i.e., 89 Euros according to Jeune Afrique [

42], and are more likely to consume dibiterie meat than people with higher income. This result could be explained by the fact that individuals with high incomes pay more attention to the “health” factor linked to meat consumption. The quality is generally requested by the better-off. This result is all the more supported by the study on the purchasing decision factors for dibiterie meat carried out by Orou Seko et al. [

39] among consumers within dibiteries in Dakar. According to these authors, the majority of consumers surveyed (61%) were “less concerned” by the health dimension (quality and safety) when buying braised meat in dibiteries. In addition, in the dibiteries hygiene and good production practices are often not mastered by the staff. Consequently, the products from these restaurants are often of doubtful microbiological quality or do not meet the international standards required for human consumption [

43,

44]. The installation of dibiteries in popular neighbourhoods with low or diversified income allows them to be closer to the target customers who do not care about the quality of the products consumed [

13].

The results also showed that the size of the family between “2 and 5 persons” negatively affects the consumption of dibiterie meat. This means that the smaller the household is, the less it consumes dibiterie meat. In Senegal, the majority of households are large (on average 8.3 people) and most often live in difficult and precarious conditions [

45]. For the latter, it is cheaper to buy a meal for the group to vary the monotonous eating habits. It is thus difficult for these types of families to diversify meals within households. They are therefore faced with a certain dietary monotony which forces some family members to go for out-of-home catering in order to diversify their evening [

8]. This situation therefore suggests that the dibiterie meat constitutes a food supplement to support the monotonous diets of low-income and large households. The result contradicts the tendency of high meat consumption described in urban areas.

The results of the study showed that attitude (convenience), perceived social pressure, the expertise of the dibiterie, health, perception of the link between meat consumption and NCDs, gender, and age of consumers influence the intention to consume dibiterie meat in households in the Dakar region.

In the first model, attitude (convenience), perceived social pressure, and perceived behavioural control explain 97.15% of the variance of intention to consume dibiterie meat. The studies by Boucher et al. [

29] on the intention to consume at least five servings of vegetables and fruit each day and Giampietri and Del Giudice [

46] on the purchase of food in short food supply chains had obtained certainly high proportions of variance, but lower than our study (75% and 73%, respectively). Therefore, the theory of planned behaviour [

24] is an effective predictor of intention to consume dibiterie meat.

Among these factors, convenience (attitude) is the main determinant regardless of the model, and it turns out to be very important for consumers. This result differs from that of the studies by Gao et al. [

47] and Giampietri and Del Giudice [

46] who indicated that among the attitude variables, loyalty was the main determinant of intention. However, in our study, convenience had a positive influence on intention, indicating that consumers of dibiterie meat find its price favourable and its sanitary impact beneficial on their health, and thus, are more willing to consume this product. Consumers are therefore motivated or feel capable to consume dibiterie meat despite its price, and above all highlight its perceived beneficial impact on their health. These factors tend to induce an increased consumption of red meat and therefore an increased risk of developing an NCD. In the context of high consumption, the design and implementation of nutrition education interventions, and promoting good practices in the prevention of NCDs may be necessary. The positive influence of attitude on intention has also been reported by certain studies carried out on the determinants of food choice [

29,

34,

35,

48]. However, Blanchard et al. [

48] and Boucher et al. [

29] found that attitude is a significant predictor of intention to consume fruits and vegetables, but not the best. On the other hand, other studies have shown that attitude, especially convenience, has a negative influence on intention; thus, indicating that consumers with a high propensity to save money are less willing to buy food in short food supply chains [

46,

49].

However, perceived social pressure negatively affected the intention to consume dibiterie meat. This result indicates that the consumer is under pressure from his social network which contributes to reducing his intention to consume dibiteries meat. In the context of low revenue and the large size of the family, people may hide when consuming meat to avoid being qualified as selfish. We can conclude that the relatives and important people for the consumer, such as his family, friend, doctor, or religious guide would disapprove of his consuming dibiterie meat, especially being aware of the link associated with this act to the development of NCDs. In addition, the consumption of dibiterie meat is seen as an act that promotes individualism in Senegal, hence their greater disapproval in face of the risks of developing an NCD. The social network, therefore, seems to be very important in developing the intention of the populations of Dakar to consume dibiterie meat. The negative effect of the perceived social pressure on the intention would favour the reduction in the consumption of meat and by extension a reduction in the risks of developing an NCD. Consequently, in the context of high meat consumption, interventions promoting a healthy lifestyle and eating habits could be implemented through communication and awareness campaigns on the media (radio, television, and social networks). In addition, traditional dance fairs could also be places for disseminating messages on healthy eating behaviours. Finally, the strategy that appears to be the most cost-effective could involve teachers in schools broadcasting messages in order to change the behaviour of a large number of children’s families. Unlike our study, some authors found that perceived social pressure did not help predict participants’ intention to consume vegetables and fruit [

29,

48,

50].

In addition to the direct variables of the TCP, model 3 of the present study allowed us to show that the expertise of dibiterie, health, perception of the link between meat consumption and NCDs, gender, and age also have a significant influence on the intention to consume dibiterie meat. Indeed, this model is the most explanatory and allows us to state that all the variables included explain about 98% of the variance of intention.

However, the perception of the quality of dibiterie meat, the “expertise of the dibiterie” and “health” components related to dibiterie meat, as well as consumer perception of the link between meat consumption and NCDs, positively influence behavioural intention. This means that a consumer will tend to consume dibiterie meat if: (i) the dibiterie has proven expertise in processing meat, (ii) he is aware of the impact of animal fat and the bad hygiene of the meat on his health, and (iii) he is also aware of the risks of NCDs associated with the consumption of red meat.

Regarding gender and age, they positively and negatively influence intention, respectively. In the Dakar region, females largely tend to consume dibiteries meat in the household. However, within the dibiteries, it is mostly men who buy and consume dibiterie meat [

39]. Moreover, the negative influence of age on intention means that the older the participants are, the less they intend to consume meat from dibiteries. It is the age groups of 20–30 years and 30–40 years that are most present when buying and consuming braised meat in dibiteries [

39].

In summary, a consumer would be motivated to consume dibiterie meat in households if he or she feels able to do so, perceives less social pressure, if the dibiterie has proven expertise in the grilling of meat, if the person is aware of the impact of animal fat and the poor hygiene of the dibiterie on his health, if the consumer is aware of the risks of NCDs associated with the consumption of red meat, and more if the person is female and in the 20–40 age group (

Figure 2). Interventions aimed at preventing or controlling NCDs by promoting the adoption of healthy eating behaviours should take into account all of these factors which significantly determine the intention to consume dibiterie meat.

Apart from the widely documented link between the daily consumption of red meat and the development of non-communicable diseases, a diet low in fruits and vegetables may also contribute to an increased risk of heart disease, stroke, and certain types of cancer [

51,

52,

53]. Indeed, according to Hernandez-Rodas et al. [

54], diet directly influences the development of obesity and specific pathologies such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). High energy intake in the form of fat, a diet low in fruit and vegetables, and lack of physical activity are the major problems. Worldwide, 1.7 million deaths (2.8% of all deaths) can be attributed to insufficient fruit and vegetable consumption. Low intake of fruits and vegetables is estimated to account for approximately 14% of deaths associated with gastrointestinal cancer, 11% of deaths associated with heart disease, and 9% of stroke-related deaths each year worldwide [

55]. Factors affecting access to fresh fruits and vegetables are complex and include income, gender, education, age, geographic location (rural vs. urban), accessibility, availability, quality, adequate transportation, and lack of food-related skills, including preparation, handling, and storage [

56].