Do We Really Have to Scale Up Local Approaches? A Reflection on Scalability, Based upon a Territorial Prospective at the Burkina Faso–Togo Border

Abstract

1. Introduction

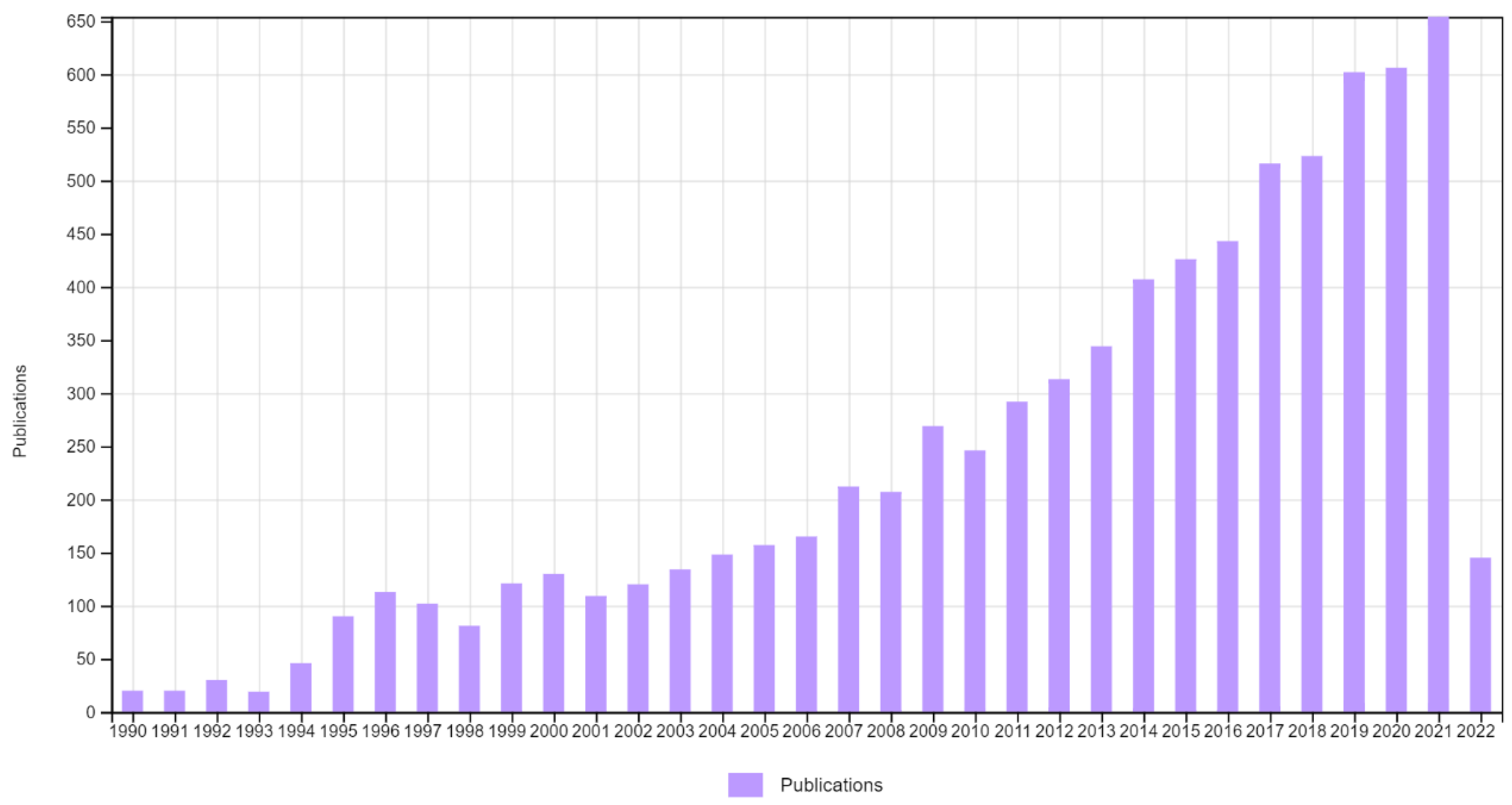

2. Scaling Up Territorial Studies: An Initial Analysis

2.1. Navigating between Two Normative Pitfalls

2.1.1. The Drivers Promoting Scalability

2.1.2. Scalability, the Primacy of Localism and Alternative Positions

- -

- Knowledge produced and mobilized. As far as knowledge is concerned, it is also necessary to insist, with Agrawal [19], on the danger of introducing a hierarchy between local and academic sciences (which may be a bias of the injunction to scale-up in the sense of generalizing). What is important is to produce contextual and activable knowledge; reality is a continuum from indigenous/local and academic spheres, with multiple hybridizations);

- -

- Modalities, methods and practices, depending on the context and purpose of action (emergency, development, academic research, etc.);

- -

- The supposed beneficiaries of the results (researchers, technicians, civil society organizations, policy makers, etc.).

2.2. Characterizing Non-Scalability Positively

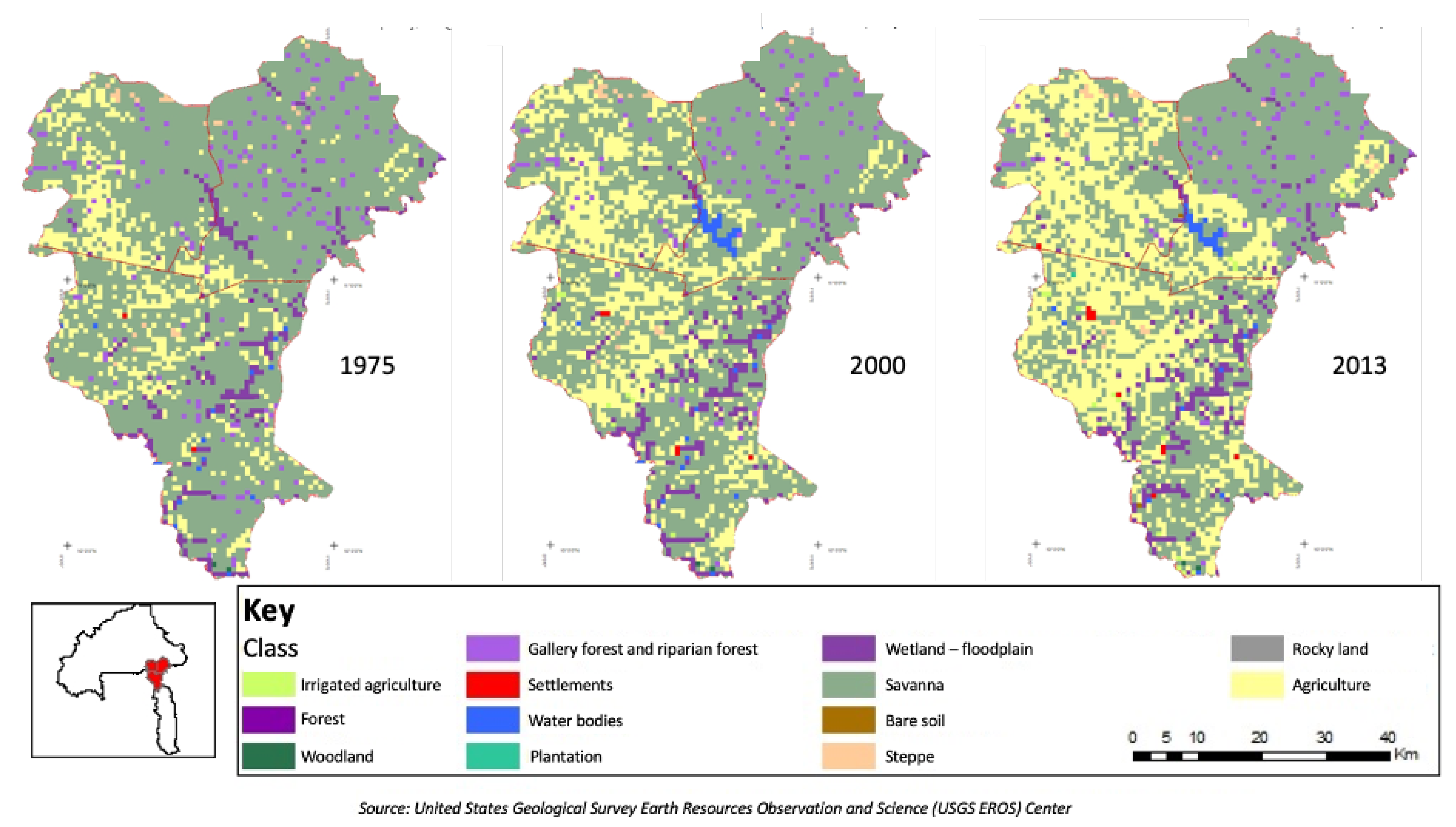

3. Narrating in Order to Denaturalize: A Territorial Prospective on Transhumance at the Border of Togo and Burkina Faso

4. Lessons from the Field: Ecology of Contexts, the Limits of Scalability and the Power of Relationships

4.1. Unfolding Processes, Revealing Relationships

4.2. Engaging in Transformative Action

4.3. Sustainability and Its Political Underpinning

- General calls for “inclusion—of women and young people” did not specify the factors and forms of their exclusion, what they were to be included in, the distinct conditions of different groups within these categories of women and young people or power relations and compromises that defined their circumstances. These apparently risk-free demands had no political cost: they went no further than an agreed-upon declaration of intent that stifled any discussion of social issues.

- Recommendations for scaling up failed to consider states of crisis or breakdowns that were apparent across a number of scales and in a range of ways. The cross-border territories between the Sahel and coast were affected by tensions in socioeconomic relations and a deterioration in relations with public authorities which, in the Sahel, have led to the “jihadisation of the agrarian question” [48]. Moreover, such recommendations ignored intermediate (local, meso-economic) forms of institutional arrangement and stability, which are in crisis at present, but were nonetheless essential to secure livelihoods and production systems and to allow them to evolve.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Driving Forces | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Cross border cooperation | Entente Cross-border cooperation is dynamic and effective: twinning, agreements, inter-municipal cooperation, joint planning of projects. | Non-Cooperation There is no inter-municipal cooperation: the municipalities see their powers transferred to the central administration. | Administrative retreat The administration lags behind the communities: problems on both sides of the border hamper cross-border cooperation. | A local parliament A local cross-border parliament: coexistence of the current institutions and a “Gourma Country”, with administrative, budgetary and security powers. | A wall A wall separates Togo and Burkina Faso, trade is ultra-regulated and greatly reduced. |

| B. Preservation of ecosystems | Lush nature The ecosystem (forests, animals, waterways) is lush with extensive and diverse resources functioning together in balance. | Desert A vast desert space characterized by the weakness of its flora and fauna, and the drying up of water bodies. | Degradation Significant reduction in natural ecosystems, strong pressure from agricultural activities, drastic reduction in fauna and flora, poisoning of waters, ecological imbalance. | ||

| C. Demographic growth | Managed growth Population growth rate is well controlled, families can look after their children who are in school. | Trends The population doubles and demographic growth is at 2.8%. | The boom continues High population growth, high total fertility rate. | Demographic decline Demographic decline with high mortality, falling birth rate. | |

| D. Human capital | Quality Quality education and vocational training in line with actual needs available to all. | An education desert There are no more schools. The population is illiterate and lacks professional skills relevant to its socio-economic needs. | Discrimination Only part of the population has access to education and training. | Obscurantism People are educated in systems specializing in a given ideology. | |

| E. Mines | El dorado Modern, sustainable mining with transparent management that allows the entire population to benefit from its positive impacts. | Capture A minority exploits and profits from the country’s mineral resources without regard for the environment and the interests of the people. | Anarchy Proliferation of small-scale mining sites with anarchic practices causing environmental degradation. | Non-Exploitation Mineral wealth is not exploited. | Nothing left There is nothing left to exploit. |

| F. Local governance | Transparency Governance by locally elected officials. Decentralization is a reality and the principles of accountability, transparency, participation, gender equality and operationality are respected. | A Centralized deadlock Decentralization is called into question. Local governance is by appointees who exercise power without accountability to the grassroots in an opaque and unilateral manner. | Unclear governance Decentralization remains theoretical with little transfer of powers and resources. Transparency and accountability are limited. Local elected officials have little authority. | Feudality The territory is dominated by local potentates, management of the commons is familial and ethnocentric, resources are confiscated by organized and violent pseudo-landowners. | Turmoil The territory is dominated by extremists, rights are violated, the whole system is questioned. |

| G. Professional structures | The leadership of POs Local professional organizations (POs) are well organized and dynamic and influence public policy. | Failure There is confusion between professional and political organizations. POs prioritize the wishes of the government over those of the organization. | Misappropriation The objectives of POs are distorted in the pursuit of self- and sectional interest and profit. | The collapse of POs Break-up of professional organizations. Actors depend on individuals or family organizations for representation. The sectors are dominated by private and political actors. | |

| H. Security | Peace Communities collaborate with security forces in a cross-border defence strategy which employs robots, preventing community conflict and ensuring the free movement of goods and people in a secure environment. | Chaos The population is in a situation of widespread insecurity. Cross-border collaboration between security services and the population has broken down. There are tensions within the security services. | Self-Defence Growing mistrust among the population and towards the forces of law and order sees communities set up self-defence groups. | The far west War between communities. |

References

- AL-Agele, H.A.; Nackley, L.; Higgins, C.W. A Pathway for Sustainable Agriculture. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankiyeva, A.K.; Huang, I.Y. Innovations and productiveness in agriculture: How far could they take us? Cent. Asian Econ. Rev. 2019, 2, 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- Chatty, D. Negotiating authenticity and translocality in Oman: The “desertscapes” of the Harasiis tribe. In Regionalizing Oman; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska, A.; Stopa, M.; Inglot-Brzęk, E. Innovativeness and entrepreneurship: Socioeconomic remarks on regional development in peripheral regions. Econ. Sociol. 2021, 14, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.D.F.; Gomes da Silva, F.; Ferreira, S.; Teixeira, M.; Damásio, H.; Dinis Ferreira, A.; Gonçalves, J.M. Innovations in Sustainable Agriculture: Case Study of Lis Valley Irrigation District, Portugal. Sustainability 2019, 11, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourisseau, J.-M.; Ancey, V. Une Approche Territoriale et Anticipatrice Pour Une Transhumance Apaisée à La Frontière Entre Le Togo et Le Burkina Faso—Synthèse; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremmen, B.; Blok, V.; Bovenkerk, B. Responsible Innovation for Life: Five Challenges Agriculture Offers for Responsible Innovation in Agriculture and Food, and the Necessity of an Ethics of Innovation. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2019, 32, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. Le Métier de Chercheur: Regard d’un Anthropologue; Sciences En Questions; Quæ: Versailles, France, 2001; pp. 1–108. [Google Scholar]

- Olivier de Sardan, J.-P. La Revanche Des Contextes: Des Mésaventures De L’ingénierie Sociale En Afrique Et Au-Delà; Editions Karthala: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- List, J.A. The Voltage Effect: How to Make Good Ideas Great and Great Ideas Scale; Currency: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, W. Défaire le Dèmos. Le Néolibéralisme, une Révolution Furtive; Éditions Amsterdam: Paris, France, 2021; 288p. [Google Scholar]

- Rangé, C.; Magnani, S.; Ancey, V. “Pastoralisme” et “insécurité” en Afrique de l’Ouest; Revue Internationale des études du Développement; IEDES: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 115–150. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, K. The great transformation. In The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time; Farrar & Rinehart: New York, NY, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Murray Li, T. The Will to Improve; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mosse, D. Cultivating Development: An Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hibou, B. La Bureaucratisation Du Monde à L’ère Néolibérale; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Caillé, A. Au-delà de l’intérêt (Éléments d’une théorie anti-utilitariste de l’action I). Rev. Du Mauss 2008, 31, 175–200. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen, K.I.; Niamir-Fuller, M.; Bensada, A.; Waters-Bayer, A. A Case of Benign Neglect: Knowledge Gaps about Sustainability in Pastoralism and Rangeland; United Nations Environment Programme and GRID-Arendal: 2019. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/27530 (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Agrawal, A. Dismantling the divide between indigenous and scientific knowledge. Dev. Chang. 1995, 26, 413–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, E.F. Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered; [1973]; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, E.O. Utopies Réelles; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tsing, A.L. Le Champignon de la fin du Monde: Sur la Possibilité de vie Dans les Ruines du Capitalism; La Découverte/Empêcheurs de penser en rond: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, M.; Bellon, S. Generalization without Universalization: Towards an Agroecology Theory. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 42, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koestler, A. The Ghost in the Machine; Hutchinson: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, M. L’agrécologie et la troisième position. In La Transition Agroécologique: Quelles Perspectives en France et Ailleurs; Hubert, B., Couvet, D., Eds.; Académie Agriculture: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bland, W.L.; Bell, M.M. A Holon Approach to Agroecology. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2007, 5, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsing, A.L. Vers une théorie de la non-scalabilité, translated from english by Julien, L. Multitudes 2021, 82, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, P.; Axelos, M.; Beckert, M.; Callois, J.M.; Dugué, J.; Esnouf, C.; Herbinet, B.; Valceschini, E. Nouvelles Questions de Recherche en Bioéconomie. Nat. Sci. Sociétés 2019, 27, 433–437. Available online: https://www.cairn.info/revue-natures-sciences-societes-2019-4-page-433.htm (accessed on 23 May 2022). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Corniaux, C.; Ancey, V.; Touré, I.; Camara, A.; Cesaro, J.-D. Pastoral mobility, from a sahelian to a sub-regional issue. In A New Emerging Rural World. An Overview of Rural Change in Africa, Atlas for the NEPAD Rural Futures Programme, 2nd ed.; Pesche, D., Losch, B., Imbernon, J., Eds.; Cirad: Montpellier, France, 2016; 76p. [Google Scholar]

- Mercandalli, S.; Losch, B. Une Afrique Rurale en Mouvement. Dynamiques et Facteurs des Migrations au Sud du Sahara; FAO: Rome, Italy; CIRAD: Montpellier, France, 2018; 60p. [Google Scholar]

- Benjaminsen, T.A.; Ba, B. Why Do Pastoralists in Mali Join Jihadist Groups? A Political Ecological Explanation. J. Peasant. Stud. 2018, 46, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krätli, S.; Toulmin, C. Farmer-Herder Conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa? A Research Paper for AFD; Research Report; IIED: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-78431-828-4. Available online: http://pubs.iied.org/10208IIED (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Pellerin, M. Listening to Herders in West Africa and the Sahel: What Future for Pastoralism in the Face of Insecurity and its Impacts? Report Réseau Billital Maroobé: Rome, Italy, 2021; 163p, Available online: https://www.maroobe.com/index.php/publications/rapports (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Corniaux, C.; Thébaud, B.; Gautier, D. La mobilité commerciale du bétail entre le Sahel et les pays côtiers: L’avenir du convoyage à pied. Nomadic Peoples 2012, 16, 6–25. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43123909 (accessed on 23 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Gonin, A.; Gautier, D. Shift in Herders’ Territorialities from Regional to Local Scale: The Political Ecology of Pastoral Herding in Western Burkina Faso. Pastoralism 2015, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourisseau, J.-M.; Bélières, J.-F.; Bourgeois, R.; Soumaré, M.; Rasolofo, P.; Guengant, J.-P.; Bougnoux, N.; Losch, B.; Ramanitriniony, H.K.; Coulibaly, B.; et al. Penser Ensemble L’avenir D’un Territoire. Diagnostic et Prospective Territoriale au Mali et à Madagascar (Études de l’AFD); AFD: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://www.afd.fr/index.php/fr/penser-ensemble-avenir-territoire (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Murdoch, J. Post-Structuralist Geography: A Guide to Relational Space; Thousand Oaks: Sage, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.; Haider, L.J.; Stålhammar, S.; Woroniecki, S. A relational turn for sustainability science? Relational thinking, leverage points and transformations. Ecosyst. People 2020, 16, 304–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumwood, V. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Jansson, Å.; Rockström, J.; Olsson, P.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chapin, F.S.; Westley, F. Reconnecting to the biosphere. Ambio 2011, 40, 719–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfiglioli, A.M. Pastoralisme, agro-pastoralisme et retour: Itinéraires sahéliens. Sociétés pastorales et Développement. Cah. Des Sci. Hum. 1990, 26, 255–266. Available online: https://www.documentation.ird.fr/hor/fdi:31594 (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Krätli, S. Valuing Variability: New Perspectives on Climate Resilient Drylands Development; de Jode, H., Ed.; IIED: London, UK, 2015; Available online: http://pubs.iied.org/10128IIED.html (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- FAO. Pastoralism—Making Variability Work; FAO Animal Production and Health Paper No. 185; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, P. Sustainability as a norm. Soc. Philos. Technol. Q. Electron. J. 1997, 2, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, B.; Ison, R. Institutionalising understandings: From resource sufficiency to functional integrity. In A Paradigm Shift in Livestock Management: From Resource Sufficiency to Functional Integrity; Kammili, T., Hubert, B., Tourrand, J.-F., Eds.; Hohhot’s Workshop: Avignon, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Poudiougou, I. Mali: De la Ruralisation du Djihad à la Djihadisation de la Question Agraire. AOC. 2022. Available online: https://aoc.media/analyse/2022/01/20/mali-de-la-ruralisation-du-djihad-a-la-djihadisation-de-la-question-agraire/ (accessed on 23 May 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ancey, V.; Sourisseau, J.-M.; Corniaux, C. Do We Really Have to Scale Up Local Approaches? A Reflection on Scalability, Based upon a Territorial Prospective at the Burkina Faso–Togo Border. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10977. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710977

Ancey V, Sourisseau J-M, Corniaux C. Do We Really Have to Scale Up Local Approaches? A Reflection on Scalability, Based upon a Territorial Prospective at the Burkina Faso–Togo Border. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):10977. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710977

Chicago/Turabian StyleAncey, Véronique, Jean-Michel Sourisseau, and Christian Corniaux. 2022. "Do We Really Have to Scale Up Local Approaches? A Reflection on Scalability, Based upon a Territorial Prospective at the Burkina Faso–Togo Border" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 10977. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710977

APA StyleAncey, V., Sourisseau, J.-M., & Corniaux, C. (2022). Do We Really Have to Scale Up Local Approaches? A Reflection on Scalability, Based upon a Territorial Prospective at the Burkina Faso–Togo Border. Sustainability, 14(17), 10977. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710977