Abstract

The manuscript presents a thematic analysis of a U.S. adult sample’s self-reported motives and perception of environmental activists’ motives to engage in pro-environmental behavior via a qualitative online survey. I identified themes using a two-stage coding procedure. First, undergraduate research assistants coded all content into 1 or more of 17 inductive content categories. Second, I examined the categories and created five themes based on both inductive and theoretical considerations: (a) harm and care, (b) purity, (c) waste and efficiency, (d) spreading awareness, and (e) self-interest (mostly non-financial). Some themes (harm and care; preserving purity; and self-interest) were consistent with previous research and theory, but themes of waste and efficiency and spreading awareness have been less explored by previous work as key motivators of pro-environmental behavior, suggesting ripe avenues for future research. Conversely, some factors that have been proposed by previous research as key possible motives of pro-environmental behavior were not described by participants in the present work. The endorsement of themes was qualitatively similar across individuals’ descriptions of their own vs. environmental activists’ motives. Collectively, these findings suggest that individuals’ descriptions of common motives for pro-environmental behavior partially aligns with factors commonly proposed in environmental psychology literature, but key discrepancies warrant further investigation.

1. Introduction

What motivates people to take pro-environmental action? Previous work has taken a variety of largely quantitative approaches to answering this question, including examining the effectiveness of knowledge-based interventions [1,2,3], considering the role of moral attitudes [4,5,6], emotions [7,8], social identities [9], and social norms [10,11]. In the present work, I take a complementary, qualitative approach: directly asking people what motivates themselves and others to act.

As pointed out by other work [12,13], conducting qualitative research in the field of environmental psychology can provide insights into how survey respondents relate to commonly used theoretical constructs and reveal important themes neglected by previous theory and research. For example, Lewis and colleagues’ work [12] revealed that many Americans (and especially people of color) defined “environmental issues” more broadly than typically conceptualized by quantitative researchers. These findings motivated later quantitative work [14] further revealing that in the US, people of color were more likely than whites to consider “human-oriented issues” (e.g., poverty, lack of access to grocery stores) as “environmental” issues. Other qualitative work has similarly provided important insights for the field of environmental psychology, including research examining perceived barriers to environmental action [15], perceived contributors to behavioral spillover [16], attitudes toward recycling [17], perceptions of environmentalists [18], and which “objects of care” people perceive to be threatened by climate change [19].

Here, I use qualitative thematic analysis to examine described motives for engaging in pro-environmental behavior (PEB). As I explore below, previous work examining how individuals become intentional, active agents of positive environmental change has been largely quantitative in nature. This quantitative work has provided key insights for researchers and practitioners. Yet, it has not examined whether the theoretical components considered most important by researchers align with how lay individuals consider motives for engaging in PEB—a gap the present work aims to address.

1.1. What Are Individuals’ Self-Perceptions of Motives for PEB?

Considering that many individuals engage in at least some PEBs, it is worth evaluating individuals’ self-described reasons for engaging in PEB. For example, despite the fact that the US has one of the world’s highest per-capita carbon footprints [20], most Americans do regularly engage in PEB such as recycling [21]. Although individuals are not always aware of, or honest about, their own motives for PEB [22,23], examining individuals’ stated motives for PEB may reflect how individuals’ explain their PEB to others, which motives are salient when they reflect on their own PEB, and perhaps in some cases how they attempt to convince others to engage in PEB. Thus, in this sense, individuals’ self-described motives can reflect both their actual motives and socially normative or appropriate reasons for engaging in PEB. Furthermore, examining individuals’ stated motives for PEB can help researchers to gain insight into narratives and motivations leading individuals to take action [24], and to examine whether theoretical perspectives of environmental motives broadly used in environmental psychology, such as moral foundations theory [4,5,6,25], the norm activation model [26,27,28], and goal-framing theory [29,30], are aligned with individuals’ own self-descriptions of their motives.

1.2. How Do Individuals Perceive Environmental Activists’ Motives for PEB?

Because individuals’ self-descriptions of motives behind their own behaviors carries unique strength and weaknesses, it may also be worth considering individuals’ perceptions of others’ motives, which carries different and largely complementary strengths and weaknesses. For example, individuals may be less prone to social desirability biases when describing others’ motives than their own, suggesting the possibility that less socially desirable motive themes could be identified when considering others’ motives. Further, it is valuable to understand the sorts of motives that individuals ascribe to others’ PEB, in part because individuals’ awareness of what motivates others is key in coordinating collective responses to environmental challenges. Because individuals, on average, tend to assume that most others are not engaging in PEB (particularly for less visible behaviors) [31,32], in the present work I focus on the reference group of environmental activists (see Supplementary Materials for a pilot study supporting this choice), for whom individuals may more likely to find PEB salient. Previous work suggests the possibility that individuals might ascribe unique motives to these individuals, such as using environmental advocacy to promote leftist social ideas [33].

1.3. Present Research

In the present work, I evaluate which motives participants commonly reference to support (a) their own PEB and (b) environmental activists’ PEB. I used qualitative methodology and adopted a thematic analysis approach (grounded in Braun and Clarke’s, reflexive thematic analysis approach [34,35]) which allows for detailed analysis of textual qualitative responses. Braun and Clarke [35] argue for using reflexive thematic analysis, as opposed to another qualitative method such as interpretative phenomenological analysis, when research aims are centered around identifying common themes of individuals’ experiences centered in social contexts with practical implications (rather than individuals’ personal sense-making), the sample size is larger than 10 and results are not in the form of interviews—all of which are true in the present work. In this sense, I was less interested in the ideographic approach (i.e., unique details of specific responses) and more interested in the thematic approach (i.e., consistently identified themes across multiple responses). My research questions involved examining which themes participants would identify for their own and environmental activists’ motives for PEB, and whether certain themes would be specific to one group over the other.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Similar to other thematic analyses in the environmental domain [18], I used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) to recruit US adult participants. Though participants in MTurk samples tend to overrepresent younger adults and the highly educated, MTurk can be used to recruit a diverse sample of US adults, and are argued to be more diverse than in-person or university student samples [18]. Thus, I anticipated that the sample would not be perfectly representative of the U.S. population, yet expected sufficient heterogeneity to investigate and answer research questions.

Fifty-nine MTurk workers completed this survey in exchange for $1.00, of whom 7 were eliminated due to providing nonsensical responses (i.e., those obviously not intended to answer the question; e.g., writing “a good safe my life in the accident.”). It is unclear whether these participants provided these responses because they were unable to answer the questions, did not wish to answer the questions, or both. This left 52 participants in the final dataset, each providing six written responses (see below) for 312 total written responses. The sample size was selected based on the awareness that each participant would be providing six responses, such that approximately 300–350 written responses would provide adequate information power [36]. Information power refers to the concept that the amount of responses needed to adequately explore a concept in qualitative research differs based on study aim, specificity, level of theory, quality of dialogue, and type of analysis. Unlike power analysis in quantitative studies, the exact number of participants needed to obtain adequate information power cannot be calculated. Rather, it expresses the notion that researchers should consider the needed sample size for a qualitative study on a case-by-case basis.

Participants were 27 men and 25 women. Sixty-three percent identified as White/Caucasian, with 15% identifying as Black/African American, 12% as Asian, and 10% as Hispanic. Most participants were either age 25–34 (48%) or 35–44 (23%). Participants were more liberal than the general population (50% liberal/very liberal, 27% moderate, 23% conservative/very conservative). Following completion of the survey, nine participants (17%) self-identified as an environmental activist “quite a bit” or “very much”, however, comments at the end of the survey such as “this survey has made me realize that I am a little bit of an activist myself” suggested that survey tasks themselves might have influenced some participants to increase this self-identification.

2.2. Data Collection

Data was collected via an online survey. Participants first wrote about three situations in which they acted in an environmentally friendly manner (based on the prompt “Please list three different situations in which you acted in an environmentally-friendly manner. These situations can be recent things that you did, representative of things you do on a regular basis, or a situation that symbolizes something that is a particularly important part of who you are as a person.”). They next imagined an environmental activist and wrote about three situations in which this activist might act in an environmentally friendly manner following a similar prompt. After completing these two sets of open-ended prompts, they revisited their six responses and described the value that motivated them, or they imagined might have motivated the environmental activist, to act in that way for each of the six. They next completed quantitative exploratory (used for a different purpose), demographic measures, described their perception of the survey purpose, and were debriefed. Data collection was approved by the Penn State University IRB. The full survey can be viewed in Supplementary Materials.

Though not the primary focus of this research, I briefly examined the types of PEB individuals had considered to examine whether most participants had focused on a single behavior or category of behaviors. Participants reported many different PEBs, including waste management (e.g., recycling, composting), consumer behavior (e.g., reducing bottled water consumption, eating less meat), transportation behaviors (e.g., walking rather than driving), and political behaviors (e.g., reading up on politicians’ environmental stances before voting). Participants similarly noted a diversity of these types of responses for environmental activists’ PEB.

2.3. Data Analysis

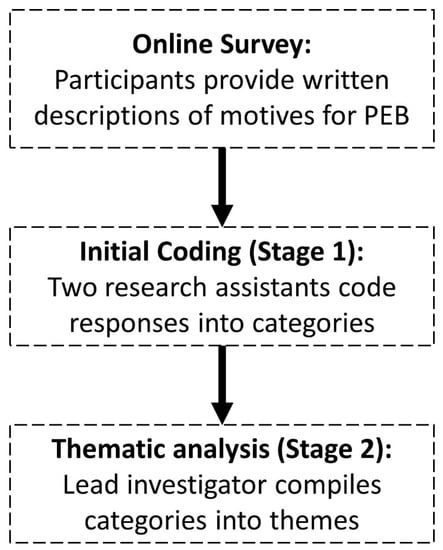

All statements describing participants’ evaluations of (a) their own motives for PEB and (b) environmental activists’ motives for PEB were compiled into a single list, decoupled from both the specific PEB and the actor. This list was added to a spreadsheet and used to conduct the thematic analysis. Based in part on procedures outlined by Braun and Clarke [34] and used in previous thematic analyses [37], categories were developed based on a two-stage, iterative procedure: in the first stage, narrower categories were first created and modified based on empirical considerations, and in the second stage, both empirical and theoretical considerations were used to create a smaller set of broader themes. I adopted an experiential approach to the thematic analysis, which suggests that I interpreted participants’ responses as reflecting internal understanding [38]. Although I agree that participants’ responses are guided by the larger social context in important ways, understanding this process is not a focus of the present work.

Figure 1 visually depicts the order in which the procedure was conducted. First, I worked with two undergraduate research assistants to code each response into one or more categories. At the time, I had completed a masters’ degree in social psychology and was broadly familiar with many of the theoretical perspectives laid out in the introduction, while in contrast, the undergraduate research assistants had limited insight into these perspectives. Initially, I examined a small subset of the written responses and identified a preliminary set of nine codes, which were shared with research assistants as examples. Research assistants were encouraged to consider other possible codes. Research assistants first coded a subset of the data: specifically, one-third of participants’ descriptions of (a) their own motives and (b) activists’ motives, while critically evaluating the initial set of categories and proposing additional categories or combination of existing categories if deemed appropriate. Categories were not mutually exclusive; responses were placed in multiple categories when appropriate. Some responses did not provide enough detail to categorize or the intended meaning was not clear to coders, these responses were not placed into a category. The two research assistants then met with me and discussed the revised list of categories to form a consensus category list. This list of seventeen categories was then used to code the full dataset. Finally, I consolidated the 17 categories into five themes capturing the most prevalent codes and most other codes, based both on empirical and theoretical approaches. During this latter process, I revisited written responses to verify that themes accurately captured the richness and meaning of participants’ responses.

Figure 1.

Flowchart visually illustrating the temporal order of steps in the procedure used in current work.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Initial Coding

The results from the initial round of coding are displayed in Table 1. Though some qualitative thematic analysis researchers [35] argue against relying on inter-rater reliability in reflexive thematic analysis, I provide values here for each code in the initial coding to show the extent to which categorization was consistent across the two coders. Overall, interrater agreement between the two research assistants was high (κ = 0.89). When the two raters disagreed on whether a particular motive applied to a given statement, that motive was scored as a 0.5 (rather than the typical 0 “does not apply” or 1 “applies) for that statement.

Table 1.

Motives participants provided for (a) their own and (b) environmental activists’ pro-environmental behavior, as identified by initial coding.

As shown in Table 1, the most prevalent of the seventeen motive categories were related to general principles: (a) protecting the environment (31% of individuals’ self-perceptions and 24% of perceptions of environmental activists) and (b) general moral concerns (26% of self-perceptions, 27% of perceptions of environmental activists). Also, fairly common, though somewhat less so than the above, was self-interest (14% of individuals’ self-perceptions vs. 20% of perceptions of environmental activists). Yet, this self-interest, in general, was not related to economic self-interest (only a total of 5% of individuals’ own self-perceptions and 3% of perceptions of environmental activists referenced economic or financial considerations at all).

Table 1 also shows that, on balance, individuals ascribed similar motives to themselves as they did to environmental activists. Although future quantitative work is needed to examine whether there are any statistical differences between these two categories, a glance at each of the columns suggests that there are not any qualitative differences between these two. These findings, on the surface, appear to contrast with previous work suggesting that individuals have negative impressions of environmental activists [39,40] and ascribe ulterior motives to these individuals (e.g., secretly advancing a leftist agenda [33]). One possibility for these findings is that participants’ responses may have been altered based on insights gained as a result of the reflective components of the task itself. Indeed, open-ended comments pro-offered by participants at the end of the survey (e.g., as noted above, “this survey has made me realize that I am a little bit of an activist myself”) support this explanation.

3.2. Thematic Analysis

Five themes were identified: harm and care, preserving purity, waste and efficiency, spreading awareness, and self-interest. Below, I discuss each theme identified here. Quotes are provided without identifying information to retain participant anonymity. Except where noted, themes were roughly similar across participants’ own motives and descriptions of environmental activists’ motives (also see Table 1). To broadly quantify the prevalence of responses and themes, I use the following guidelines (based loosely on previous work; [18,41]): the term “a majority” is used to refer to over half, “many” is used to refer to more than a quarter but less than half, “some” is used to refer to less than a quarter but more than a tenth, and “a few” is used to refer to less than a tenth.

3.3. Harm and Care

Various theoretical perspectives, including moral foundations theory [25] and dyadic morality theory [42] define the motive to prevent harm and advance well-being as a core moral motive. This motive has been argued to be a predominant motive in public discourse around environmental protection [4]. Indeed, many participants endorsed one theme in the present study reflecting this foundation: protecting the environment, advancing the welfare of humans, advancing the welfare of animals, and protecting future generations. For example, one participant wrote that environmental activists were motivated because “they don’t want to cause more harm to their environment.” Similarly, another participant wrote that “My family and I are motivated to do our part to save the environment. My family enjoys recycling knowing the ultimate overall benefits.” As shown in Table 1, a few more responses suggested that participants’ own motives were related to environmental protection, and in contrast, that environmental activists’ motives were related to protecting humans and future generations. The fact that this theme was identified suggests that individuals’ descriptions of motives of environmental behaviors align with several prevalent theories regarding this particular factor.

3.4. Preserving Purity

Some participants endorsed a second theme also reflecting a core moral foundation from moral foundations theory [25]: preserving purity. Previous research and theory suggests that this motive is salient to many regarding environmental issues [4,43,44,45], a pattern which I found evidence for in the present work. Many responses referenced ideas related to concerns about purity/pollution or aesthetic concerns and reducing litter or trash. For example, one participant wrote that they were motivated to pick up trash because “it makes the neighborhood look dirty and that people who lived their it looks like we don’t car. Trash belongs in the garbage [sic]”. Another participant wrote that they “wanted to do [their] part to not send toxic waste down the drain into the water supply”. Many responses ascribed similar motives to environmental activists, for example that “The activist values a cleaner planet for everyone” or that they were motivated “to reduce fossil fuel burning and lessen pollution”. As with harm and care, the identification of this theme suggests alignment with quantitative research and theory that has identified purity as an important factor.

3.5. Waste and Efficiency

Some participants endorsed a theme reflecting the idea of reducing waste and being efficient. For example, one participant wrote “I want to be respectful to others and try to reduce my energy as much as possible when it isn’t really needed.” Though not identified as a code in the initial coding by undergraduate research assistants, later examination revealed that a few responses tied this motive was tied to anti-consumerism; for example, one wrote “I want to be a person who wastes and consumes less. I would like for this to become part of who I am” and another wrote “anti-consumption is moral.” Responses about environmental activists reflected this theme at similar rates to those about self-motives, although unlike self-motives, no responses about environmental activists explicitly referenced anti-consumerism. For example, a participant wrote that environmental activists are motivated to “recycle and reuse instead of filling up the landfills.”

Considering the identification of reducing waste and being efficient as a key theme in the present work, the theme is arguably understudied as a motivation of pro-environmental behavior. Waste and efficiency is not described in moral foundations theory [25], although it has been suggested by proponents as a possible candidate for an additional moral foundation [46,47]. Similarly, a couple studies have examined the desire to engage in waste minimization; this work suggests that the motive falls into the moral domain [48,49]. The present work leads partial credence to this possibility, as many spontaneously noted that the desire to reduce waste motivates their own and environmental advocates’ PEB. Based on my identification of this theme, I argue that more researchers should consider the desire to minimize waste as a key motivator of some PEBs, and to understand when and why individuals are motivated to reduce waste.

3.6. Spreading Awareness

Another theme endorsed by some participants was a motive to spread awareness about environmental conservation to others. For example, one participant wrote that they were motivated by the possibility of “teaching [their] kids”, and another noted that “communication and education is a major part of being human”. Similarly, many responses ascribed similar motives to environmental activists, noting for example that environmental activists’ behavior reflected their motives to “spread knowledge to other people so that they can make educated decisions” and “It gets others involved in caring about their neighborhood”. Previous work on social diffusion of pro-environmental behaviors or opinions [50,51,52] has primarily focused on the effects of such attempted influence rather than why influencers are motivated to try to change others. Thus, based on my identification of this theme, I argue that researchers should more seriously consider when and why individuals are motivated to spread environmental awareness to others.

3.7. Self-Interest

Self-interest was identified as a theme endorsed by some participants, yet, as shown in Table 1, only a few responses directly referenced money or financial interests. Rather, other types of self-interest, such as references to personal enjoyment (i.e., anticipated positive emotions or warm glow; [53]), constituted the bulk of the self-interest theme here. For example, one participant wrote that their volunteer work “…was purely driven out of my own interest and passion of the outdoors, and wanting to be in the national forests as much as possible.” Similarly, another participant wrote “It makes me feel good, knowing I am not heavily polluting the enviroment [sic]”. Though not identified as a code by undergraduate research assistants, I note that a few participants referred to health benefits of PEB, for example by describing how they were motivated to engage in active transportation by the possibility of “helping the atmosphere and also helps you lead a healthier lifestyle.” A similar theme was echoed across participants’ descriptions of environmental activists’ motives; for example, one participant explained that environmental activists were motivated by “not eating meat, so they feel good”. Two responses involving self-interest for environmental activists’ motives (but not for participants’ own motives) referenced getting attention or admiration from other people: “giving people a chance to notice you whether that’s good or bad” and “making people see that I have a good heart”. These findings suggest that self-interest is a commonly described motive for PEB, but that consistent with other environmental psychology research [54,55], researchers and advocates might be best served to think of this concept more broadly than simply a desire to save or earn money.

Considering responses in terms of goal-framing theory [29], explanations provided in the present work generally tended to fit more along the lines of hedonic frames (i.e., motivated by anticipated positive emotions or warm glow) rather than gain frames (i.e., motivated by improving and guarding one’s resources). The lack of “gain-frame” responses could reflect the possibility that PEBs motivated by gain frames, such as buying a fuel-efficient vehicle or reinsulating one’s home to save money, were not salient or easily recalled as “environmentally friendly.” If so, this would have important implications for the accuracy of survey research asking about prior engagement in different types of PEB, as well as research on positive and negative behavioral spillover of PEB [56]. However, future work is needed to empirically assess this speculation.

3.8. Limitations and Future Directions

The findings may be specific to the sample, a convenience sample of US adults which overrepresents political liberals and young adults relative to the US public and do not represent other countries. Additionally, all responses here are self-reported and may be subject to social desirability biases [23], perhaps especially with participants who have previously participated in many MTurk studies. Future qualitative and quantitative work is needed to assess dimensions on which participants’ attributions of motives to themselves, environmental activists, and other individuals (e.g., friends and family; strangers; non-activist environmentalists) might differ [57,58].

Future quantitative work should examine predictors of each of the motives noted above, particularly the ones that have been less extensively studied in previous work. Research on moral foundations theory suggests that the harm/care moral foundation is usually more appealing to US political liberals than conservatives, while the purity moral foundation is usually more appealing to US conservatives than liberals [4,6,25] (but also see [44]). Similarly, some limited work suggests that political conservatives are more motivated by self-interest than are political liberals (i.e., pro-self vs. pro-social orientation [59]) suggesting the possibility that self-interest might be more motivating toward environmental action to the former group, though more research is needed to examine this conjecture. Similarly, work is needed to examine whether political orientation is similarly associated with the extent to which individuals endorse motives to reduce waste and promote efficiency, and to spread awareness of environmental issues. Relatedly, experiments should examine whether messages designed to appeal to these motives can promote PEB, and whether political or other individual difference factors moderate these effects.

4. Implications and Conclusions

This work reveals how individuals evaluate their own and environmental activists’ motives for engaging in pro-environmental behavior (PEB). Through thematic analysis, I identified five themes applying to both individuals’ descriptions of both their own and environmental activists’ motives for PEB: (1) harm and care, (2) preserving purity, (3) waste and efficiency, (4) spreading awareness, and (5) (typically non-financial) self-interest. Somewhat unexpectedly, and inconsistent with previous work suggesting that individuals ascribe ulterior motives to environmental activists [33], both codes and themes were largely consistent between individuals’ descriptions of their own motives vs. descriptions of environmental activists motives. This suggests that individuals’ considerations of prominent motives guiding PEBs might be more consistent across explanations of one’s own behaviors vs. explanations of others’ behavior than other research might suggest.

It is worth noting that many potential themes identified elsewhere as relevant to the promotion of PEB or stereotypes of environmental activists were not identified here. For example, the desire to fit in (i.e., social norms) has been shown to predict PEB [10,60], which was not noted by participants in the present work. Similarly, the desire for status is argued to be a key motivator of PEB [61,62], yet only two responses about environmental activists’ motives (and none about participants’ own motives; see Self-Interest) alluded to this concept. Some moral modules suggested by moral foundations theory, including fairness, loyalty, and respect for authority [25], which have been used in environmental messaging studies [5], were similarly not identified. Further, as noted above, other work has revealed that many ascribe ulterior or sinister motives to environmental activists [33,39,63], which again, was not related to themes identified here. These discrepancies could be caused in part by unawareness or unwillingness to admit the influence of social norms and other factors [22,23]. Additionally, the reflection process afforded by the writing exercise in the present study might have encouraged participants to humanize environmental activists, thus potentially decreasing ascription of conspiratorial motives to these individuals. Overall, these discrepancies potentially suggest that these pro-environmental motives, despite arguably being influential on individuals’ pro-environmental behavior as evidenced by these previous studies, may be less prevalent in individuals’ thoughts and public discourse than they are in the environmental psychology literature.

These themes shed new light onto motives behind individuals’ PEB and communication about such behaviors and provide a contrasting perspective to the mostly quantitative body of existing research on this topic. In particular, themes of waste and efficiency and spreading awareness were common, yet contributing factors to these two motivators have been rarely examined in the environmental psychology literature. This suggests that the field would benefit from additional research to understand why and in what contexts individuals are motivated to avoid being wasteful and to spread environmental awareness to others. Environmental advocates may also find these findings useful for developing new interventions to foster PEB.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su141710656/s1. Supplementary File S1: Pilot study.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Penn State University (IRB# STUDY00009070) in 2017.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is publicly available at https://osf.io/dnyk3/, accessed on 3 August 2022.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Janet Swim, Mel Mark, Jonathan Cook, and Lee Ahern for feedback on this study as a portion of the lead author’s doctoral dissertation. Thanks to Lauren Shaffer and Maire McLaughlin for helping to code content into categories, and thanks to Janet Swim for allowing use of her lab facilities and to work with her undergraduate research assistants. Thanks to anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback on this manuscript. This research was made possible in part due to support from the Penn State Psychology Department.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Geiger, N.; Swim, J.K.; Fraser, J.; Flinner, K. Catalyzing Public Engagement with Climate Change through Informal Science Learning Centers. Sci. Commun. 2017, 39, 221–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranney, M.A.; Clark, D. Climate Change Conceptual Change: Scientific Information Can Transform Attitudes. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2016, 8, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swim, J.K.; Geiger, N.; Fraser, J.; Pletcher, N. Climate Change Education at Nature-based Museums. Curator Mus. J. 2017, 60, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, M.; Willer, R. The Moral Roots of Environmental Attitudes. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsko, C. Expanding the Range of Environmental Values: Political Orientation, Moral Foundations, and the Common Ingroup. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsko, C.; Ariceaga, H.; Seiden, J. Red, White, and Blue Enough to Be Green: Effects of Moral Framing on Climate Change Attitudes and Conservation Behaviors. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 65, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosch, T. Affect and Emotions as Drivers of Climate Change Perception and Action: A Review. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 42, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harth, N.S.; Leach, C.W.; Kessler, T. Guilt, Anger, and Pride about in-Group Environmental Behaviour: Different Emotions Predict Distinct Intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, N.; Pasek, M.H.; Gruszczynski, M.; Ratcliff, N.J.; Weaver, K.S. Political Ingroup Conformity and Pro-Environmental Behavior: Evaluating the Evidence from a Survey and Mousetracking Experiments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Nolan, J.M.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. The Constructive, Destructive, and Reconstructive Power of Social Norms. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sparkman, G.; Walton, G.M. Dynamic Norms Promote Sustainable Behavior, Even If It Is Counternormative. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 1663–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, N.A.; Bravo, M.; Naiman, S.; Pearson, A.R.; Romero-Canyas, R.; Schuldt, J.P.; Song, H. Using Qualitative Approaches to Improve Quantitative Inferences in Environmental Psychology. MethodsX 2020, 7, 100943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bercht, A.L. How Qualitative Approaches Matter in Climate and Ocean Change Research: Uncovering Contradictions about Climate Concern. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 70, 102326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Lewis Jr, N.A.; Ballew, M.T.; Bravo, M.; Davydova, J.; Gao, H.O.; Garcia, R.; Hiltner, S.; Naiman, S.M.; Pearson, A.R. What Counts as an “Environmental” Issue? Differences in Issue Conceptualization by Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, I.; Nicholson-Cole, S.; Whitmarsh, L. Barriers Perceived to Engaging with Climate Change among the UK Public and Their Policy Implications. Glob. Environ. Change 2007, 17, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elf, P.; Gatersleben, B.; Christie, I. Facilitating Positive Spillover Effects: New Insights from a Mixed-Methods Approach Exploring Factors Enabling People to Live More Sustainable Lifestyles. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Ford, N.J.; Gilg, A.W. Attitudes towards Recycling Household Waste in Exeter, Devon: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. Local Environ. 2003, 8, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klas, A.; Zinkiewicz, L.; Zhou, J.; Clarke, E.J.R. “Not All Environmentalists Are Like That … ”: Unpacking the Negative and Positive Beliefs and Perceptions of Environmentalists. Environ. Commun. 2019, 13, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Leviston, Z.; Hurlstone, M.; Lawrence, C.; Walker, I. Emotions Predict Policy Support: Why It Matters How People Feel about Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 50, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldometer CO2 Emissions per Capita–Worldometer. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/co2-emissions/co2-emissions-per-capita/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- American Psychological Association. Majority of US Adults Believe Climate Change Is Most Important Issue Today; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, J.M.; Schultz, P.W.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. Normative Social Influence Is Underdetected. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely, S.; Klöckner, C.A. Social Desirability in Environmental Psychology Research: Three Meta-Analyses. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.; Barnett-Loro, C. To Support a Stronger Climate Movement, Focus Research on Building Collective Power. Front. Commun. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Haidt, J.; Nosek, B.A. Liberals and Conservatives Rely on Different Sets of Moral Foundations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 1029–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Morality and Prosocial Behavior: The Role of Awareness, Responsibility, and Norms in the Norm Activation Model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S. The Justice of Need and the Activation of Humanitarian Norms. J. Soc. Issues 1975, 31, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L. One Model to Predict Them All: Predicting Energy Behaviours with the Norm Activation Model. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenberg, S.; Steg, L. Normative, Gain and Hedonic Goal Frames Guiding Environmental Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenberg, S.; Steg, L. Goal-framing theory and norm-guided environmental behavior. In Encouraging Sustainable Behavior; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. 37–54. ISBN 0-203-14118-0. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, N.; Gore, A.; Squire, C.V.; Attari, S.Z. Investigating Similarities and Differences in Individual Reactions to the Covid-19 Pandemic and the Climate Crisis. Clim. Change 2021, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leviston, Z.; Uren, H.V. Overestimating One’s “Green” Behavior: Better-than-Average Bias May Function to Reduce Perceived Personal Threat from Climate Change. J. Soc. Issues 2020, 76, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffarth, M.R.; Hodson, G. Green on the Outside, Red on the inside: Perceived Environmentalist Threat as a Factor Explaining Political Polarization of Climate Change. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I Use TA? Should I Use TA? Should I Not Use TA? Comparing Reflexive Thematic Analysis and Other Pattern-Based Qualitative Analytic Approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss-Racusin, C.A.; Molenda, A.K.; Cramer, C.R. Can Evidence Impact Attitudes? Public Reactions to Evidence of Gender Bias in STEM Fields. Psychol. Women Q. 2015, 39, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic Analysis. 2014. Available online: https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output/821722/thematic-analysis (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Bashir, N.Y.; Lockwood, P.; Chasteen, A.L.; Nadolny, D.; Noyes, I. The Ironic Impact of Activists: Negative Stereotypes Reduce Social Change Influence. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 614–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swim, J.K.; Geiger, N. The Gendered Nature of Stereotypes about Climate Change Opinion Groups. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2018, 21, 436–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opperman, E.; Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Rogers, C. “It Feels So Good It Almost Hurts”: Young Adults’ Experiences of Orgasm and Sexual Pleasure. J. Sex Res. 2014, 51, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, C.; Gray, K. The Unifying Moral Dyad Liberals and Conservatives Share the Same Harm-Based Moral Template. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 0146167215591501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimer, J.A.; Tell, C.E.; Haidt, J. Liberals Condemn Sacrilege Too: The Harmless Desecration of Cerro Torre. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2015, 6, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimer, J.A.; Tell, C.E.; Motyl, M. Sacralizing Liberals and Fair-Minded Conservatives: Ideological Symmetry in the Moral Motives in the Culture War. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2017, 17, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kantenbacher, J.; Miniard, D.; Geiger, N.; Yoder, L.; Attari, S.Z. Young Adults Face the Future of the United States: Perceptions of Its Promise, Perils, and Possibilities. Futures 2022, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Nosek, B.A.; Haidt, J.; Iyer, R.; Koleva, S.; Ditto, P.H. Mapping the Moral Domain. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, J.; Haidt, J.; Koleva, S.; Motyl, M.; Iyer, R.; Wojcik, S.P.; Ditto, P.H. Moral Foundations Theory: The Pragmatic Validity of Moral Pluralism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 47, pp. 55–130. ISBN 0065-2601. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, L.; Bishop, B. A Moral Basis for Recycling: Extending the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Grunert-Beckmann, S.C. Values and Attitude Formation towards Emerging Attitude Objects: From Recycling to General, Waste Minimizing Behavior. Adv. Consum. Res. 1997, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L. Social Influence Approaches to Encourage Resource Conservation: A Meta-Analysis. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divakaran, B.M.; Nerbonne, J. Building a Climate Movement through Relational Organizing. Interdiscip. J. Partnersh. Stud. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, N.; Swim, J.K.; Glenna, L.L. Spread the Green Word: A Social Community Perspective into Environmentally Sustainable Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 561–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufik, D.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Steg, L. Acting Green Elicits a Literal Warm Glow. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Relationships between Value Orientations, Self-Determined Motivational Types and pro-Environmental Behavioural Intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, Z.; Jansson, J.; Bengtsson, M. Consumer Motivations for Sustainable Consumption: The Interaction of Gain, Normative and Hedonic Motivations on Electric Vehicle Adoption. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, A.; Carrico, A.R.; Raimi, K.T.; Truelove, H.B.; Araujo, B.; Yeung, K.L. Meta-Analysis of pro-Environmental Behaviour Spillover. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratliff, K.A.; Howell, J.L.; Redford, L. Attitudes toward the Prototypical Environmentalist Predict Environmentally Friendly Behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varpio, L.; O’Brien, B.; Rees, C.E.; Monrouxe, L.; Ajjawi, R.; Paradis, E. The Applicability of Generalisability and Bias to Health Professions Education’s Research. Med. Educ. 2021, 55, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lange, P.A.M.; Bekkers, R.; Chirumbolo, A.; Leone, L. Are Conservatives Less Likely to Be Prosocial Than Liberals? From Games to Ideology, Political Preferences and Voting: Are Conservatives Less Prosocial? Eur. J. Personal. 2012, 26, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A Room with a Viewpoint: Using Social Norms to Motivate Environmental Conservation in Hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Van den Bergh, B. Going Green to Be Seen: Status, Reputation, and Conspicuous Conservation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, S.E.; Sexton, A.L. Conspicuous Conservation: The Prius Halo and Willingness to Pay for Environmental Bona Fides. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2014, 67, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, S. The Conspiracy-Effect: Exposure to Conspiracy Theories (about Global Warming) Decreases pro-Social Behavior and Science Acceptance. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 87, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).