Reimbursement Costs of Auditing Financial Assets Measured by Fair Value Model in Jordanian Financial Firms’ Annual Reports

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Historical Development of the Fair Value Model

2.1. Fair Value Development Overview

“Financial assets at fair value through profit or loss, Available-for-sale financial assets, Loans and receivables and Held-to-maturity investments”.

2.2. Jordan Profile

3. Theoretical Perspective, Fair Value Implementation Background, and Hypotheses Development

3.1. Theoretical Perspective

3.2. Fair Value Implementation Background and Hypotheses Development

4. Research Data and Methodology

4.1. Sample Selection

4.2. Research Design

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Descriptive and Correlation Statistics

5.2. Univariate Analysis

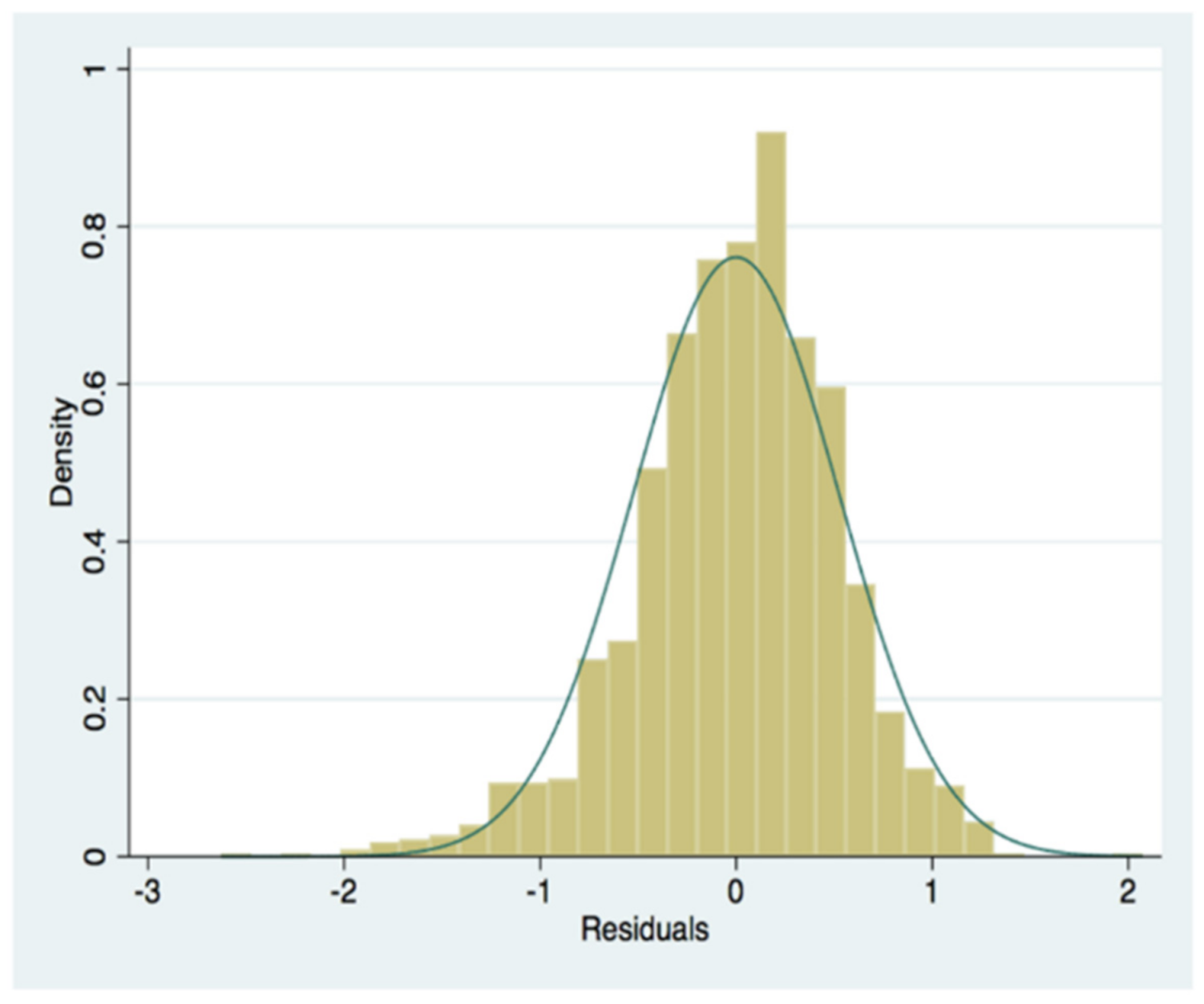

5.3. Regression Analysis

6. Sensitivity Analysis

6.1. Excluding (Big Four Auditors)

6.2. Excluding the Year of the Crisis (2008)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Terzi, S.; Oktem, R.; Sen, I.K. Impact of adopting international financial reporting standards: Empirical evidence from Turkey. Int. Bus. Res. 2013, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlif, H.; Achek, I. IFRS adoption and auditing: A review. Asian Rev. Account. 2016, 24, 338–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiechter, P.; Novotny-Farkas, Z. The impact of the institutional environment on the value relevance of fair values. Rev. Account. Stud. 2017, 22, 392–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAS Plus. IAS 39—Financial Instruments: Recognition and Measurement. 2019/2022. Available online: https://www.iasplus.com/en/standards/ias/ias39 (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- IAS Plus. Financial Instruments. IASB Board Meeting 18–20 October 2005, London, UK, Deloitte Global Services Limited. 2019. Available online: https://www.iasplus.com/en/meetingnotes/iasb/2005/agenda_0510 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- IFRS Foundation. Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting. Available online: https://www.iasplus.com/en/standards/other/framework (accessed on 26 October 2019).

- IFRS Foundation. Who Uses IFRS Standards? Use of IFRS Standards by Jurisdiction. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/use-around-the-world/use-of-ifrs-standards-by-jurisdiction/#analysis/ (accessed on 26 October 2019).

- Landsman, W.R. Is fair value accounting information relevant and reliable? Evidence from capital market research. Account. Bus. Res. 2007, 37, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.E.; Israeli, D. Disentangling mandatory IFRS reporting and changes in enforcement. J. Account. Econ. 2013, 56, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, K.; Irving, J.H.; Sokolowsky, J. Accounting choice and the fair value option. Account. Horiz. 2011, 25, 487–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taplin, R.; Yuan, W.; Brown, A. The use of fair value and historical cost accounting for investment properties in China. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2014, 8, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, C.; Leuz, C. Did fair-value accounting contribute to the financial crisis? J. Econ. Perspect. 2010, 24, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penman, S.H. Financial reporting quality: Is fair value a plus or a minus? Account. Bus. Res. 2007, 37, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettredge, M.L.; Xu, Y.; Yi, H.S. Fair value measurements and audit fees: Evidence from the banking industry. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2014, 33, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, S.M.; Taylor, M.H.; Wu, Y.J.; Trotman, K.T. Mind the gap: Why do experts have differences of opinion regarding the sufficiency of audit evidence supporting complex fair value measurements? Contemp. Account. Res. 2019, 36, 1417–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahat, Y.A.; Dunne, T.; Fifield, S.; Power, D.M. The impact of IFRS 7 on the significance of financial instruments disclosure: Evidence from Jordan. Account. Res. J. 2016, 29, 241–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaha, K.; Khlif, H. Adoption of and compliance with IFRS in developing countries: A synthesis of theories and directions for future research. J. Account. Emerg. Econ. 2016, 6, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullatif, M. Auditing fair value estimates in developing countries: The case of Jordan. Asian J. Bus. Account. 2016, 9, 101–140. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, R. IFRS–10 years later. Account. Bus. Res. 2016, 46, 545–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharasis, E.E.; Prokofieva, M.; Alqatamin, R.M.; Clark, C. Fair Value Accounting and Implications for the Auditing Profession: Historical Overview. Account. Financ. Res. 2020, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, O.; Jack, L. In pursuit of legitimacy: A history behind fair value accounting. Br. Account. Rev. 2011, 43, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharasis, E.E.; Prokofieva, M.; Clark, C. Fair value accounting and audit fees: The moderating effect of the Global Financial Crisis in Jordan. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of Accounting, Business, and Economics (ICABEC) Sustainable Business Innovation: New Normal Going Forward, Universiti Malaysia, Terengganu, Malaysia, 16–17 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alharasis, E.E.; Clark, C.; Prokofieva, M. External Audit Fees and Fair Value Disclosures among Jordanian Listed Companies: Does the Type of Corporate Industry Matter? Asian J. Bus. Account. 2022, 14, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Alharasis, E.E. The Impact of Fair Value Disclosure on Audit Fees of Jordanian Listed Firms. Ph.D. Thesis, Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alharasis, E.E.; Haddad, H.; Shehadeh, M.; Tarawneh, A.S. Abnormal Monitoring Costs Charged for Auditing Fair Value Model: Evidence from Jordanian Finance Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3476. [Google Scholar]

- Shehadeh, M.; Alharasis, E.E.; Haddad, H.; Hasan, E.F. The Impact of Ownership Structure and Corporate Governance on Capital Structure of Jordanian Industrial Companies. Wseas Trans. Bus. Econ. 2022, 19, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-W.S.; Feng, Z.-Y.A.; Zaher, A.A. Fair value and economic consequences of financial restatements. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020, 34, 101–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozen, R.C. Is it fair to blame fair value accounting for the financial crisis? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2009, 87, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Fiechter, P. The effects of the fair value option under IAS 39 on the volatility of bank earnings. J. Int. Account. Res. 2011, 10, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Hwang, L.-S. Country-specific factors related to financial reporting and the value relevance of accounting data. J. Account. Res. 2000, 38, 181279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuz, C.; Verrecchia, R.E. The economic consequences of increased disclosure. J. Account. Res. 2000, 38, 91–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siekkinen, J. Value relevance of fair values in different investor protection environments. Account. Forum 2016, 40, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Htaybat, K. IFRS Adoption in Emerging Markets: The Case of Jordan. Aust. Account. Rev. 2018, 28, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.E. Measurement in financial reporting: The need for concepts. Account. Horiz. 2013, 28, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wong, T.; Young, D. Challenges for implementation of fair value accounting in emerging markets: Evidence from China. Contemp. Account. Res. 2012, 29, 538–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, L.; Marei, A.; Al-Jabaly, S.; Aldaas, A. Moderating the role of top management commitment in the usage of computer-assisted auditing techniques. Accounting 2021, 7, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahat, Y.; Omran, M.A.; AbuGhazaleh, N.M. Factors affecting the development of accounting practices in Jordan: An institutional perspective. Asian Rev. Account. 2018, 26, 464–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Gao, J.; Zheng, W. Accounting standards, earnings transparency and audit fees: Convergence with IFRS in China. Aust. Account. Rev. 2018, 28, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siam, W.; Abdullatif, M. Fair value accounting usefulness and implementation obstacles: Views from bankers in Jordan. Account. Asia 2011, 11, 83–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.; Hassan, S.; Iqbal, A.; Khan, M.F.A. Impact of corporate governance on audit fee: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. World Appl. Sci. J. 2014, 30, 645–651. [Google Scholar]

- Boolaky, P.K.; Omoteso, K.; Ibrahim, M.U.; Adelopo, I. The development of accounting practices and the adoption of IFRS in selected MENA countries. J. Account. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 8, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.-S.; Hassan, M.K. Global and regional integration of the Middle East and North African (MENA) stock markets. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2008, 48, 482–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhtaybat, L.; Hutaibat, K.; Al-Htaybat, K. Mapping corporate disclosure theories. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 2012, 10, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marei, A.; Iskandar, E.D.T.B.M. The impact of Computer Assisted Auditing Techniques (CAATs) on development of audit process: An assessment of Performance Expectancy of by the auditors. Int. J. Manag. Commer. Innov. 2019, 7, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Akra, M.; Ali, M.J.; Marashdeh, O. Development of accounting regulation in Jordan. Int. J. Account. 2009, 44, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuboori, Z.M.; Singh, H.; Haddad, H.; Al-Ramahi, N.M.; Ali, M.A. Intellectual Capital and Firm Performance Correlation: The Mediation Role of Innovation Capability in Malaysian Manufacturing SMEs Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakurár, M.; Haddad, H.; Nagy, J.; Popp, J.; Oláh, J. The service quality dimensions that affect customer satisfaction in the Jordanian banking sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatnawi, S.A.; Marei, A.; Hanefah, M.M.; Eldaia, M.; Alaaraj, S. Audit Committee and Financial Performance in Jordan: The Moderating Effect of Ownership Concentration. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2021, 17, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Shatnawi, S.A.; Marei, A.; Hanefah, M.M.; Eldaia, M. The Effect of Audit Committee on Financial Performance of Listed Companies in Jordan: The Moderating Effect of Enterprise Risk Management. J. Manag. Inf. Decis. Sci. 2021, 25, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Alexeyeva, I.; Mejia-Likosova, M. The impact of fair value measurement on audit fees: Evidence from financial institutions in 24 European countries. Int. J. Audit. 2016, 20, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abernathy, J.L.; Kubick, T.R.; Masli, A.N. The effect of general counsel prominence on the pricing of audit services. J. Account. Public Policy 2019, 38, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhababsah, S. Ownership structure and audit quality: An empirical analysis considering ownership types in Jordan. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2019, 35, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangchan, P.; Habib, A.; Jiang, H.; Bhuiyan, M.B.U. Fair Value Exposure, Changes in Fair Value and Audit Fees: Evidence from Australian Real Estate Industry. Aust. Account. Rev. 2020, 30, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, E.E. Auditors, specialists, and professional jurisdiction in audits of fair values. Contemp. Account. Res. 2020, 37, 245–276. [Google Scholar]

- Wray, B.; Li, S. Managerial Ability and Fair Value Accounting: Evidence from Non-financial Firms. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2021, 19, 666–685. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, C.; Dargusch, P.; Hill, G. Assessing How Big Insurance Firms Report and Manage Carbon Emissions: A Case Study of Allianz. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.F.T.; Percy, M.; Hu, F. Fair value accounting for non-current assets and audit fees: Evidence from Australian companies. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2015, 11, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, R.; Panaretou, A.; Shakespeare, C. Fair value accounting: Current practice and perspectives for future research. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2020, 47, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharov, I.; Riedl, E.J.; Sellhorn, T. Fair value and audit fees. Rev. Account. Stud. 2014, 19, 210–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akra, M.; Hutchinson, P. Family firm disclosure and accounting regulation reform in the Middle East: The case of Jordan. Res. Account. Regul. 2013, 25, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A.; Siriviriyakul, S.; Sloan, R.G. Who’s the fairest of them all? Evidence from closed-end funds. Account. Rev. 2015, 91, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behn, B.K.; Choi, J.-H.; Kang, T. Audit quality and properties of analyst earnings forecasts. Account. Rev. 2008, 83, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Firms | Pooled | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial sample | 235 | 3290 |

| (-) Firms with missing data | (13) | (182) |

| (-) Firms belonging to the nonfinance industry | (24) | (336) |

| (-) Firms belonging to industries with less than ten firms | (72) | (1008) |

| (-) Firms using other accounting methods (firms with non-VFD) | (21) | (294) |

| Final sample | 105 | 1470 |

| Total Accepted Firms | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Financial Industry Sample | ||

| Real estate | 28 | 27 |

| Diversified Financial Services | 38 | 36 |

| Banks | 16 | 15 |

| Insurance | 23 | 22 |

| Total sample from the financial industry | 105 | 100 |

| Variable | Label | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Audit fees | LnAFEES | The natural Log of total audit fees. |

| The proportion of fair-valued assets | FV_TA | Total assets deflate a firm’s total fair-valued assets. |

| Fair value for Option | FV_Option | Firm’s total fair-valued financial assets for Option. |

| Fair-valued financial assets available for trading | FV_AFT | The firm’s total fair-valued financial assets are available for trading. |

| Fair-valued financial assets available for sale | FV_AFS | The firm’s total fair-valued financial assets are available for sale. |

| Client size | SIZE | The natural Log of a firm’s total assets. |

| Number of subsidiaries | SUBS | The number of firm’s subsidiaries or branches. |

| Return on investment | ROI | The net income by total assets. |

| Growth ratio | GROWTH | The current year’s revenues compared to last year’s revenues. |

| Receivable and inventory ratio | RECINV | The sum of total receivables and inventory divided by total assets. |

| Block-holder ownership percentage | BLOCK_OWN | The percentage of the total shares held by the block-holder investors of the total number of a firm’s shares. |

| Foreign ownership percentage | FOR_OWN | The proportion of total shares owned by foreign investors to the total number of shares in a company. |

| Institutional ownership percentage | INST_OWN | The proportion of institutional investors’ overall holdings to the total number of shares in a company. |

| Big four audit firms | BIG4 | The dummy variable is coded as 1 if the audit firm is one of the big four (PwC, KPMG, Deloitte, or E&Y), and 0 otherwise. |

| Auditor tenure | TENURE | Three-year tenure for auditors, coded 1 if the audit firm did not change, 0 if it did. |

| Unqualified opinion | OPINION | Dummy variable with a value of 1 if the company obtains an unqualified opinion and 0 if it does not. |

| Subsidiaries | SUBS | SUBS is the number of the firm’s subsidiaries. |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LnAFEES | 9.397833 | 1.085241 | 6.907755 | 12.41187 |

| FV_TA | 0.1487079 | 0.1825532 | 0.0000284 | 0.9939833 |

| FV_Option | 5,216,992 | 7.83 × 107 | 0 | 2.04 × 109 |

| FV_AFT | 5,105,472 | 3.26 × 107 | 0 | 7.16 × 108 |

| FV_AFS | 2.38 × 107 | 1.67 × 108 | 0 | 3.48 × 109 |

| SIZE | 17.32962 | 1.972169 | 13.1846 | 22.07602 |

| SUBS | 2.254422 | 3.458285 | 0 | 17 |

| ROI | 1268.633 | 762.5071 | 29 | 2590 |

| LEV | 1500.548 | 850.372 | 32 | 2763 |

| GROWTH | 1.635998 | 3.356879 | −2.864738 | 22.52969 |

| RECINV | 0.262524 | 1.02215 | 0 | 37.63185 |

| BLOCK_OWN | 0.5608269 | 0.2379901 | 0.0493206 | 0.964 |

| FOR_OWN | 0.1296985 | 0.2306555 | 0 | 0.910538 |

| INST_OWN | 0.3357593 | 0.2766584 | 0 | 0.9793341 |

| BIG4 | 0.4047619 | 0.4910129 | 0 | 1 |

| TENURE | 0.5326531 | 0.4991024 | 0 | 1 |

| OPINION | 0.8768707 | 0.3286973 | 0 | 1 |

| N | 1470 | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. LnAFEES | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||

| 2. FV_Option | 0.137 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| 3. FV_AFT | 0.291 *** | −0.003 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| 4. FV_AFS | 0.312 *** | 0.0640 * | 0.514 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 5. SIZE | 0.830 *** | 0.144 *** | 0.271 *** | 0.288 *** | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 6. SUBS | 0.229 *** | 0.022 | 0.216 *** | 0.201 *** | 0.250 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 7. ROI | 0.330 *** | 0.028 | 0.122 *** | 0.121 *** | 0.357 *** | −0.161 *** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 8. LEV | 0.538 *** | 0.0796 ** | 0.135 *** | 0.156 *** | 0.523 *** | −0.0829 ** | 0.268 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 9. GROWTH | −0.0752 ** | −0.011 | 0.0782 ** | 0.024 | −0.0558 * | −0.006 | 0.0536 * | −0.022 | 1.000 | |||||||

| 10. RECINV | 0.0589 * | 0.006 | 0.036 | 0.006 | 0.041 | −0.0588 * | 0.0766 ** | 0.0553 * | −0.015 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 11. BLOCK_OWN | 0.128 *** | −0.003 | −0.006 | −0.011 | 0.100 *** | −0.0968 *** | 0.123 *** | 0.161 *** | 0.0542 * | 0.041 | 1.000 | |||||

| 12. FOR_OWN | 0.433 *** | 0.047 | 0.030 | 0.0612 * | 0.361 *** | −0.035 | 0.185 *** | 0.317 *** | −0.036 | 0.012 | 0.287 *** | 1.000 | ||||

| 13. INST_OWN | 0.232 *** | 0.036 | 0.025 | 0.035 | 0.173 *** | −0.013 | 0.115 *** | 0.149 *** | 0.0607 * | 0.002 | 0.538 *** | 0.421 *** | 1.000 | |||

| 14. BIG4 | 0.575 *** | 0.0784 ** | 0.135 *** | 0.154 *** | 0.514 *** | 0.0628 * | 0.223 *** | 0.256 *** | −0.0614 * | 0.0652 * | 0.249 *** | 0.278 *** | 0.295 *** | 1.000 | ||

| 15. TENURE | 0.167 *** | −0.012 | 0.009 | 0.027 | 0.131 *** | 0.0879 *** | 0.013 | 0.111 *** | −0.035 | 0.020 | 0.107 *** | 0.0569 * | 0.0861 *** | −0.028 | 1.000 | |

| 16. OPINION | 0.0531 * | 0.025 | 0.043 | 0.047 | 0.044 | −0.147 *** | 0.235 *** | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.029 | 0.137 *** | 0.113 *** | 0.126 *** | 0.0897 *** | −0.015 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. LnAFEES | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| 2. FV_TA | −0.181 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 3. SIZE | 0.830 *** | −0.269 *** | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 4. SUBS | 0.229 *** | −0.0787 ** | 0.250 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 5. ROI | 0.330 *** | −0.005 | 0.357 *** | −0.161 *** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 6. LEV | 0.538 *** | −0.182 *** | 0.523 *** | −0.0829 ** | 0.268 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 7. GROWTH | −0.0752 ** | 0.0515 * | −0.0558 * | −0.006 | 0.0536 * | −0.022 | 1.000 | |||||||

| 8. RECINV | 0.0589 * | 0.035 | 0.041 | −0.0588 * | 0.0766 ** | 0.0553 * | −0.015 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 9. BLOCK_OWN | 0.128 *** | −0.017 | 0.100 *** | −0.0968 *** | 0.123 *** | 0.161 *** | 0.0542 * | 0.041 | 1.000 | |||||

| 10. FOR_OWN | 0.433 *** | −0.0684 ** | 0.361 *** | −0.035 | 0.185 *** | 0.317 *** | −0.036 | 0.012 | 0.287 *** | 1.000 | ||||

| 11. INST_OWN | 0.232 *** | 0.012 | 0.173 *** | −0.013 | 0.115 *** | 0.149 *** | 0.0607 * | 0.002 | 0.538 *** | 0.421 *** | 1.000 | |||

| 12. BIG4 | 0.575 *** | −0.159 *** | 0.514 *** | 0.0628 * | 0.223 *** | 0.256 *** | −0.0614 * | 0.0652 * | 0.249 *** | 0.278 *** | 0.295 *** | 1.000 | ||

| 13. TENURE | 0.167 *** | 0.021 | 0.131 *** | 0.0879 *** | 0.013 | 0.111 *** | −0.035 | 0.020 | 0.107 *** | 0.0569 * | 0.0861 *** | −0.028 | 1.000 | |

| 14. OPINION | 0.0531 * | 0.138 *** | 0.044 | −0.147 *** | 0.235 *** | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.029 | 0.137 *** | 0.113 *** | 0.126 *** | 0.0897 *** | −0.015 | 1.000 |

| Variable | Mean | t-Value (sig) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Firms with F.V.O. vs. Firms with Non-F.V.O. Disclosures | |||

| (F.V.O. = 1) N = 67 firm-year observation | (F.V.O. = 0) N = 1403 firm-year observation | ||

| LnAFEES | 10.986 | 9.3219 | −12.9414 *** |

| Panel B: Firms with AFT vs. firms with non-AFT disclosures | |||

| (AFT =1) N = 953 firm-year observation | (AFT =0) N = 517 firm-year observation | ||

| LnAFEES | 9.3978 | 9.0911 | −8.1560 *** |

| Panel C: Firms with A.F.S. vs. firms with non-AFS disclosures | |||

| (AFS = 1) N = 1273 firm-year observation | (AFS =0) N = 197 firm-year observation | ||

| LnAFEES | 9.4533 | 9.0392 | −5.0249 *** |

| DV = LnAFEES Variables | Model 1 Coeff. (t) | Model 2 Coeff. (t) | Model 3 Coeff. (t) | Model 4 Coeff. (t) | Model 5 Coeff. (t) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.221 | 3.435 | 3.577 | 3.568 | 3.659 |

| (18.76) *** | (20.44) *** | (21.35) *** | (21.30) *** | (21.69) *** | |

| FV_TA | 0.360 | ||||

| (4.34) *** | |||||

| FV_Option | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| (1.310) | (1.390) | ||||

| FV_AFT | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| (5.88) *** | (3.74) *** | ||||

| FV_AFS | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| (5.74) *** | (3.36) *** | ||||

| SIZE | 0.319 | 0.308 | 0.301 | 0.302 | 0.297 |

| (29.21) *** | (28.44) *** | (28.08) *** | (28.13) *** | (27.53) *** | |

| SUBS | 0.025 | 0.026 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.019 |

| (5.51) *** | (5.67) *** | (4.52) *** | (4.63) *** | (4.22) *** | |

| ROI | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (2.83) *** | (3.11) *** | (2.83) *** | (2.84) *** | (2.78) *** | |

| LEV | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (8.94) *** | (8.74) *** | (8.51) *** | (8.41) *** | (8.36) *** | |

| GROWTH | −0.005 | −0.005 | −0.007 | −0.006 | −0.007 |

| (−1.240) * | (−1.190) | (−1.700) * | (−1.380) | (−1.690) | |

| RECINV | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.016 |

| (1.120) | (1.290) | (1.130) | (1.310) | (1.170) | |

| BLOCK_OWN | −0.274 | −0.275 | −0.275 | −0.272 | −0.268 |

| (−3.83) *** | (−3.83) *** | (−3.87) *** | (−3.83) *** | (−3.79) *** | |

| FOR_OWN | 0.566 | 0.575 | 0.596 | 0.585 | 0.598 |

| (7.95) *** | (8.03) *** | (8.40) *** | (8.26) *** | (8.47) *** | |

| INST_OWN | 0.092 | 0.100 | 0.105 | 0.104 | 0.102 |

| (1.440) | (1.560) | (1.650) | (1.630) | (1.610) | |

| BIG4 | 0.446 | 0.443 | 0.438 | 0.437 | 0.436 |

| (12.72) *** | (12.57) *** | (12.57) *** | (12.53) *** | (12.55) *** | |

| TENURE | 0.098 | 0.115 | 0.116 | 0.112 | 0.116 |

| (3.13) *** | (3.68) *** | (3.74) *** | (3.63) *** | (3.76) *** | |

| OPINION | 0.011 | 0.030 | 0.019 | 0.023 | 0.015 |

| (0.240) | (0.670) | (0.440) | (0.520) | (0.350) | |

| N | 1470 | 1470 | 1470 | 1470 | 1470 |

| Prob > F | (13) *** | (13) *** | (13) *** | (13) *** | (18) *** |

| Adj. R2 | 76.06% | 75.96% | 76.37% | 76.36% | 77% |

| Mean VIF | 1.38 | 1.36 | 1.38 | 1.37 | 1.38 |

| DV = LnAFEES Variables | Model (1) Coeff. (t) | Model (2) Coeff. (t) | Model (3) Coeff. (t) | Model (4) Coeff. (t) | Model (5) Coeff. (t) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.314 | 2.535 | 2.697 | 2.689 | 2.783 |

| (14.02) *** | (15.83) *** | (16.81) *** | (16.76) *** | (17.17) *** | |

| FV_TA | 0.366 | ||||

| (4.20) *** | |||||

| FV_Option | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| (1.120) | (1.200) | ||||

| FV_AFT | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| (5.77) *** | (3.67) *** | ||||

| FV_AFS | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| (5.63) *** | (3.31) *** | ||||

| SIZE | 0.375 | 0.364 | 0.356 | 0.356 | 0.351 |

| (35.92) *** | (35.32) *** | (34.82) *** | (34.86) *** | (34.12) *** | |

| SUBS | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.019 |

| (5.14) *** | (5.24) *** | (4.11) *** | (4.21) *** | (3.79) *** | |

| ROI | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (2.68) *** | (2.98) *** | (2.72) *** | (2.73) *** | (2.67) *** | |

| LEV | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (7.84) *** | (7.66) *** | (7.43) *** | (7.33) *** | (7.27) *** | |

| GROWTH | −0.007 | −0.007 | −0.009 | −0.008 | −0.009 |

| (−1.630) | (−1.590) | (−2.10) ** | (−1.780) * | (−2.09) ** | |

| RECINV | 0.284 | 0.265 | 0.250 | 0.248 | 0.241 |

| (4.14) *** | (3.85) *** | (3.66) *** | (3.64) *** | (3.54) *** | |

| BLOCK_OWN | −0.162 | −0.164 | −0.164 | −0.161 | −0.158 |

| (−2.17) ** | (−2.19) ** | (−2.23) ** | (−2.18) ** | (−2.15) ** | |

| FOR_OWN | 0.556 | 0.565 | 0.587 | 0.576 | 0.590 |

| (7.44) *** | (7.52) *** | (7.89) *** | (7.75) *** | (7.96) *** | |

| INST_OWN | 0.212 | 0.220 | 0.224 | 0.222 | 0.221 |

| (3.20) *** | (3.31) *** | (3.40) *** | (3.36) *** | (3.36) *** | |

| TENURE | 0.026 | 0.044 | 0.046 | 0.042 | 0.046 |

| (0.820) | (1.370) | (1.430) | (1.330) | (1.450) | |

| OPINION | 0.032 | 0.052 | 0.040 | 0.044 | 0.036 |

| (0.680) | (1.110) | (0.870) | (0.950) | (0.780) | |

| N | 1470 | 1470 | 1470 | 1470 | 1470 |

| Prob > F | (12) *** | (12) *** | (13) *** | (12) *** | (14) *** |

| Adj. R2 | 73.69% | 73.39% | 76.37% | 73.96% | 74.19% |

| Mean VIF | 1.34 | 1.32 | 1.38 | 1.33 | 1.35 |

| DV = LnAFEES Variables | Model 1 Coeff. (t) | Model 2 Coeff. (t) | Model 3 Coeff. (t) | Model 4 Coeff. (t) | Model 5 Coeff. (t) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.163 | 3.380 | 3.524 | 3.498 | 3.592 |

| (17.85) *** | (19.46) *** | (20.35) *** | (20.20) *** | (20.58) *** | |

| FV_TA | 0.370 | ||||

| (4.30) *** | |||||

| FV_Option | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| (1.230) | (1.310) | ||||

| FV_AFT | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| (5.65) *** | (3.70) *** | ||||

| FV_AFS | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| (5.14) *** | (2.68) *** | ||||

| SIZE | 0.321 | 0.309 | 0.303 | 0.304 | 0.299 |

| (28.38) *** | (27.59) *** | (27.27) *** | (27.37) *** | (26.79) *** | |

| SUBS | 0.026 | 0.026 | 0.021 | 0.022 | 0.020 |

| (5.42) *** | (5.51) *** | (4.38) *** | (4.57) *** | (4.15) *** | |

| ROI | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (2.56) ** | (2.94) *** | (2.66) *** | (2.63) *** | (2.60) *** | |

| LEV | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (8.39) *** | (8.17) *** | (7.92) *** | (7.89) *** | (7.81) *** | |

| GROWTH | −0.004 | −0.004 | −0.006 | −0.005 | −0.006 |

| (−0.830) | (−0.790) | (−1.300) | (−0.990) | (−1.300) | |

| RECINV | 0.226 | 0.208 | 0.194 | 0.194 | 0.186 |

| (3.29) *** | (3.01) *** | (2.83) *** | (2.83) *** | (2.73) *** | |

| BLOCK_OWN | −0.276 | −0.277 | −0.277 | −0.276 | −0.271 |

| (−3.71) *** | (−3.70) *** | (−3.74) *** | (−3.72) *** | (−3.67) *** | |

| FOR_OWN | 0.537 | 0.546 | 0.567 | 0.555 | 0.569 |

| (7.24) *** | (7.31) *** | (7.66) *** | (7.50) ** | (7.71) *** | |

| INST_OWN | 0.096 | 0.108 | 0.113 | 0.111 | 0.110 |

| (1.440) | (1.600) | (1.700) | (1.670) | (1.650) | |

| BIG4 | 0.443 | 0.438 | 0.433 | 0.434 | 0.432 |

| (12.12) *** | (11.91) *** | (11.89) *** | (11.91) *** | (11.91) *** | |

| TENURE | 0.093 | 0.110 | 0.110 | 0.110 | 0.113 |

| (2.86) *** | (3.41) *** | (3.44) *** | (3.44) *** | (3.52) *** | |

| OPINION | 0.005 | 0.027 | 0.016 | 0.021 | 0.000 |

| (0.110) | (0.580) | (0.350) | (0.450) | (1.310) | |

| N | 1470 | 1470 | 1470 | 1470 | 1470 |

| Prob > F | (13) *** | (13) *** | (13) *** | (13) *** | (15) *** |

| Adj. R2 | 76.07% | 75.77% | 76.31% | 76.21% | 76.47% |

| Mean VIF | 1.39 | 1.37 | 1.39 | 1.39 | 1.40 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alharasis, E.E.; Tarawneh, A.S.; Shehadeh, M.; Haddad, H.; Marei, A.; Hasan, E.F. Reimbursement Costs of Auditing Financial Assets Measured by Fair Value Model in Jordanian Financial Firms’ Annual Reports. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710620

Alharasis EE, Tarawneh AS, Shehadeh M, Haddad H, Marei A, Hasan EF. Reimbursement Costs of Auditing Financial Assets Measured by Fair Value Model in Jordanian Financial Firms’ Annual Reports. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):10620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710620

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlharasis, Esraa Esam, Ahmad Saleem Tarawneh, Maha Shehadeh, Hossam Haddad, Ahmad Marei, and Elina F. Hasan. 2022. "Reimbursement Costs of Auditing Financial Assets Measured by Fair Value Model in Jordanian Financial Firms’ Annual Reports" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 10620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710620

APA StyleAlharasis, E. E., Tarawneh, A. S., Shehadeh, M., Haddad, H., Marei, A., & Hasan, E. F. (2022). Reimbursement Costs of Auditing Financial Assets Measured by Fair Value Model in Jordanian Financial Firms’ Annual Reports. Sustainability, 14(17), 10620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710620