Impact of Teenage EFL Learners’ Psychological Needs on Learning Engagement and Behavioral Intention in Synchronous Online English Courses

Abstract

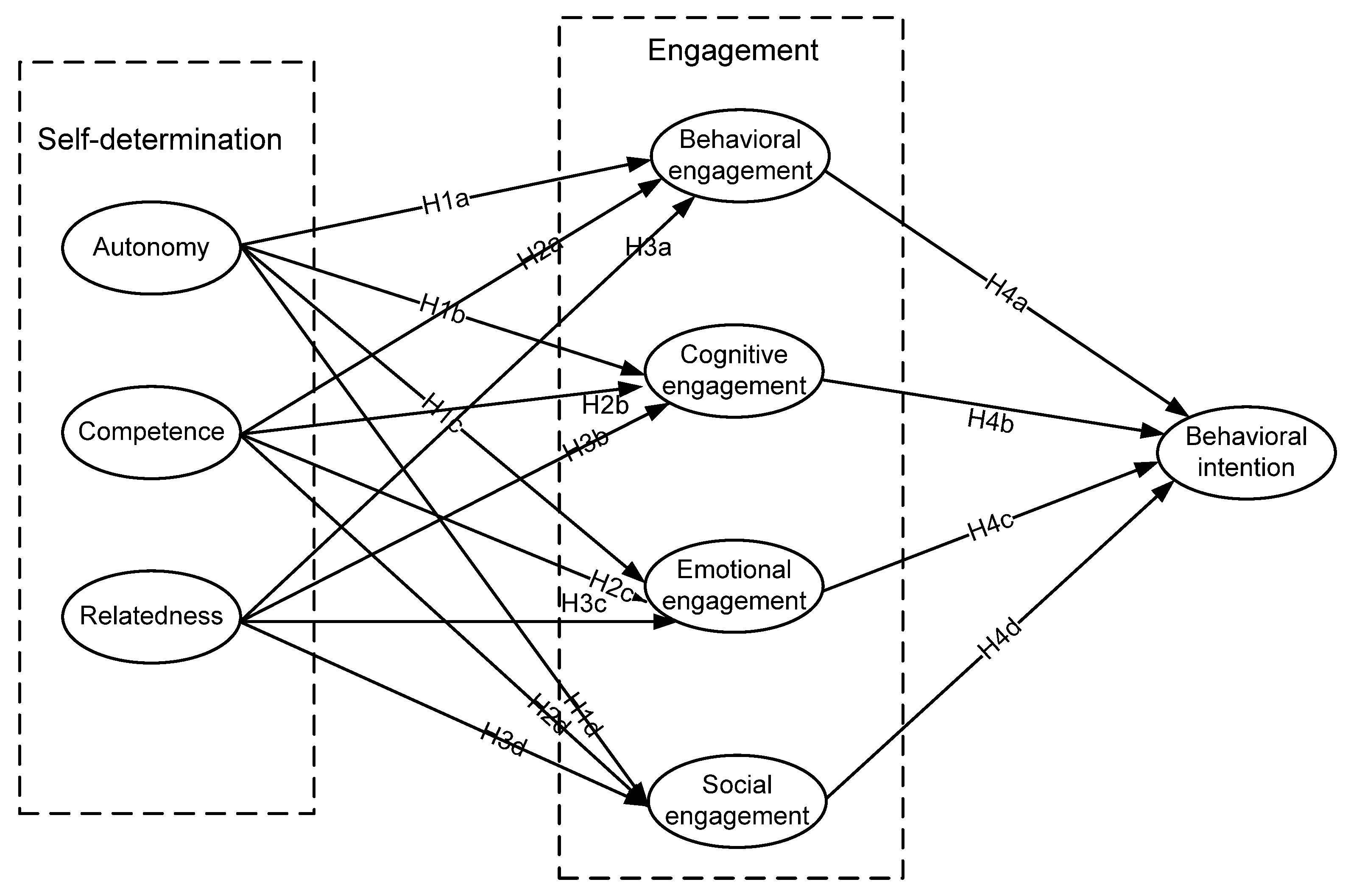

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Technology-Assisted Language Learning

2.2. Basic Psychological Needs

- a.

- Behavioral (H1a; H2a; H3a)

- b.

- Cognitive (H1b; H2b; H3b)

- c.

- Emotional (H1c; H2c; H3c)

- d.

- Social (H1d; H2d; H3d)

2.3. Engagement and Behavioral Intention

2.4. Proposed Research Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Context and Participants

3.2. Measurement Instruments

3.3. Research Design, Data Collection, and Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Results of Quantitative Analysis

4.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.2. Measurement Model

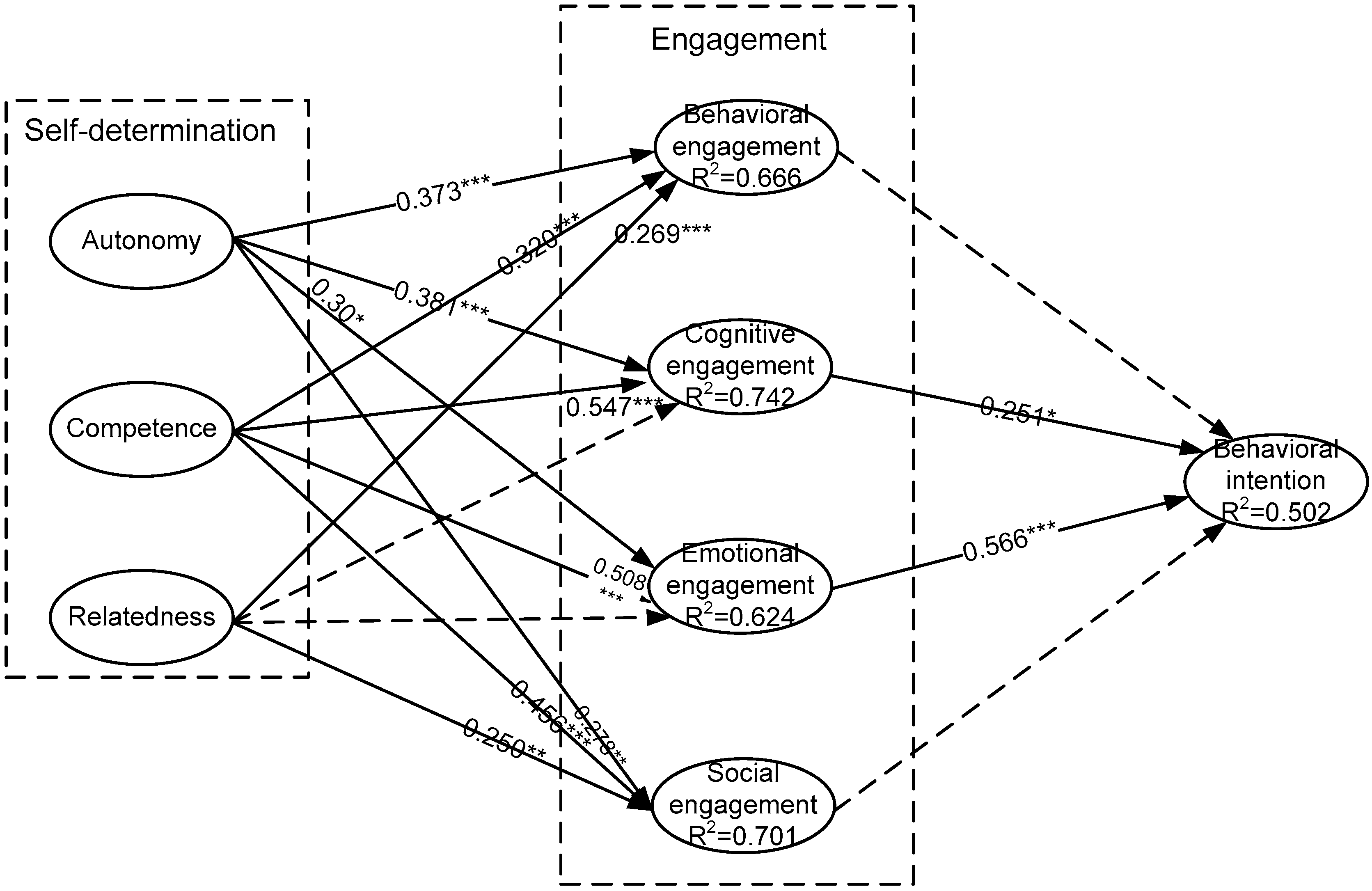

4.1.3. Structural Model

4.2. Results of Qualitative Analysis

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

5.1.1. Basic Psychological Needs Are Effective Predictors of Teenage EFL Learners’ Online Learning Engagement

5.1.2. Cognitive and Emotional Engagement as Positive Factors on Teenage EFL Learners’ Behavioral Intention

5.1.3. Student-Generated Problems and Comments on Improving Engagement

5.2. Implications and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral intentions | BI1: I intend to completely switch over to the e-learning platform to learn English. | Liu et al. (2009) [58] & Joo, So, Kim (2018) [57] |

| BI2: I intend to increase my use of the e-learning platform to learn English in the future. | ||

| BI3: If e-learning platform becomes diverse in the future, I intend to use it to learn English frequently even after graduation. | ||

| Fulfillment of the need for autonomy | FNA1: I feel like I can make a lot of inputs to deciding how I learn English online. | Sun et al. (2019) [46] & Agnesia (2010) [53] |

| FNA2: If it were up to me whether or not to do the online English learning task, I would still have done it. | ||

| FNA3: I did online English class tasks because I wanted to. | ||

| Fulfillment of the need for competence | FNC1: When learning English online, I get many chances to show my capability. | Sun et al. (2019) [46] |

| FNC2: When learning English online, I often feel very capable. | ||

| FNC3: I feel very competent in learning English online. | ||

| Fulfillment of the need for relatedness | FNR1: People are pretty friendly towards me when I am learning English online. | Sun et al.(2019) [46] |

| FNR2: I really like the people learning English online with me. | ||

| FNR3: I get along with people when I am learning English online. | ||

| Behavioral engagement | BehaE1: When I’m in the online English class, I listen very carefully. | Reeve (2013) [54] |

| BehaE2: I try hard to do well in online English class. | ||

| BehaE3: When learning English online, I work as hard as I can. | ||

| Cognitive engagement | CogE1: I try to make all the different ideas fit together and make sense when learning English online. | Reeve(2013) [54] |

| CogE2: When doing work for online English class, I try to relate what I’m learning to what I already know. | ||

| CogE3: I make up my own examples to help me understand the important concept I study when learning English online. | ||

| Emotional engagement | EmoE1: When we work on something in online English class, I feel interested. | Reeve (2013) [54] |

| EmoE2: Online English class is fun. | ||

| EmoE3: I enjoy learning new things in online English class. | ||

| EmoE4: When learning English online, I feel good. | ||

| Social engagement | SocE1: I felt comfortable interacting with other participants when learning in the online English class. | Strong et.al (2012) [55] & Bergdahl et.al. (2020) [49] & Liu et.al (2010) [56] |

| SocE2: I felt comfortable participating in the online English class discussions, like answering instructor’s questions. | ||

| SocE3: I am satisfied with my English teachers’ use of online platform (e.g., QQ/Wechat/DingTalk) to keep track of my progress /give feedback. | ||

| SocE4: When learning English online, I engage in simultaneous learning interaction with others via online platform (e.g., QQ/Wechat/DingTalk) |

References

- Hodges, C.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.; Trust, T.; Bond, A. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educ. Rev. Online 2020. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Dhawan, S. Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2020, 49, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, H. Predicting Chinese university students’ e-learning acceptance and self-regulation in online English courses: Evidence from Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) during COVID-19. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211061379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, G.; Dewaele, J.M. Understanding Chinese high school students’ foreign language enjoyment: Validation of the Chinese version of the foreign language enjoyment scale. System 2018, 76, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Liang, J.C.; Li, M.; Tsai, C.C. The relationship between English language learners’ motivation and online self-regulation: A structural equation modelling approach. System 2018, 76, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Park, S.; Shin, H.W. Investigating the link between engagement, readiness, and satisfaction in a synchronous online second language learning environment. System 2022, 105, 102720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.K. Student engagement in K-12 online learning amid COVID-19: A qualitative approach from a self-determination theory perspective. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Zhang, W. An experimental case study on forum-based online teaching to improve student’s engagement and motivation in higher education. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.T.; Fredricks, J.; Ye, F.; Hofkens, T.; Linn, J.S. Conceptualization and assessment of adolescents’ engagement and disengagement in school: A Multidimensional School Engagement Scale. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 35, 592–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, L.; Hong, J.C.; Cao, M.; Dong, Y.; Hou, X. Exploring the role of online EFL learners’ perceived social support in their learning engagement: A structural equation model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, I.; Catalán, S.; Martínez, E. Engagement in business simulation games: A self-system model of motivational development. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiver, P.; Al-Hoorie, A.H.; Vitta, J.P.; Wu, J. Engagement in language learning: A systematic review of 20 years of research methods and definitions. Lang. Teach. Res. 2021, 13621688211001289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Zhou, S.; Cheng, X. Why do college students continue to use mobile learning? Learning involvement and self-determination theory. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 50, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.H.; Huebner, E.S.; Tian, L.L. The reciprocal relations among basic psychological need satisfaction at school, positivity and academic achievement in Chinese early adolescents. Learn Instr. 2021, 71, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahari, A. Affordances and challenges of technology-assisted language learning for motivation: A systematic review. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Meng, Z.; Tian, M.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, C.; Xiao, W. Examining EFL learners’ individual antecedents on the adoption of automated writing evaluation in China. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 32, 784–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.S.C.; Huang, Y.M.; Wu, W.C.V. Technological acceptance of LINE in flipped EFL oral training. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathali, S.; Okada, T. Technology acceptance model in technology-enhanced OCLL contexts: A self-determination theory approach. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 34, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. Examining the role of inter-group peer online feedback on wiki writing in an EAP context. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2020, 33, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, E.; Pilot, A.; Simons, P.R.J. Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in foreign language learning through Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.H.; Chen, C.H. Investigating the impacts of using a mobile interactive English learning system on the learning achievements and learning perceptions of student with different backgrounds. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2022, 35, 88–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.P.; Wang, L.L. The relationship between English language learners’ self-regulation and technology acceptance. Foreign Lang. Educ. 2020, 41, 64–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shadiev, R.; Yang, M.K.; Reynolds, B.L.; Hwang, W.Y. Improving English as a foreign language–learning performance using mobile devices in unfamiliar environments. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2020, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.C. Chinese students’ perceptions of using Google Translate as a translingual CALL tool in EFL writing. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2020, 35, 1250–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R. Does Game-Based Vocabulary Learning APP Influence Chinese EFL Learners’ Vocabulary Achievement, Motivation, and Self-Confidence? SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211003092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.F. Engaging students in an online situated language learning environment. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2011, 24, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, C.P.; Ryan, R.M. Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory Res. Educ. 2009, 7, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.C.; Jang, S.J. Motivation in online learning: Testing a model of self-determination theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.C.K.; Wang, C.V.; Levesque-Bristol, C. Reexamining the impact of self-determination theory on learning outcomes in the online learning environment. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 24, 2159–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M. Chinese university students’ acceptance of MOOCs: A self-determination perspective. Comput. Educ. 2016, 92–93, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Hameed, Z.; Yu, Y.; Islam, T.; Sheikh, Z.; Khan, S.U. Predicting the acceptance of MOOCs in a developing country: Application of task-technology fit model, social motivation, and self-determination theory. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 964–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, M.; Hew, K.F. Examining learning engagement in MOOCs: A self-determination theoretical perspective using mixed method. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2020, 17, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Nebel, S.; Beege, M.; Rey, G.D. The autonomy-enhancing effects of choice on cognitive load, motivation and learning with digital media. Learn Instr. 2018, 58, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinek, D.; Zumbach, J.; Carmignola, M. The impact of perceived autonomy support and autonomy orientation on orientations towards teaching and self-regulation at university. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 102, 101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, A.; Yesilyurt, S.; Takkac, M. The effects of autonomy-supportive climates on EFL learner’s engagement, achievement and competence in English speaking classrooms. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 3890–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Tang, L.; Yang, J.; Peng, M. Social interaction in MOOCs: The mediating effects of immersive experience and psychological needs satisfaction. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 39, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, E.; Archambault, I.; Dupéré, V. Do needs for competence and relatedness mediate the risk of low engagement of students with behavior and social problem profiles? Learn. Individ. Differ. 2020, 78, 101842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, A.; Yeşilyurt, S.; Noels, K.A.; Vargas Lascano, D.I. Self-determination and classroom engagement of EFL learners: A mixed-methods study of the self-system model of motivational development. SAGE Open 2019, 9, 2158244019853913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oga-Baldwin, W.Q.; Nakata, Y.; Parker, P.; Ryan, R.M. Motivating young language learners: A longitudinal model of self-determined motivation in elementary school foreign language classes. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 49, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.C.Y.; Rueda, R. Situational interest, computer self-efficacy and self-regulation: Their impact on student engagement in distance education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2012, 43, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Lee, J. Learning engagement and persistence in massive open online courses (MOOCS). Comput. Educ. 2018, 122, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, R.; Gurrea-Sarasa, R.; Herrando, C.; Martín-De Hoyos, M.J.; Bordonaba-Juste, V.; Utrillas-Acerete, A. The generation of student engagement as a cognition-affect-behaviour process in a Twitter learning experience. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 36, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ni, L.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, X.L.; Wang, N. Understanding students’ engagement in MOOCs: An integration of self-determination theory and theory of relationship quality. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 50, 3156–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Y. Understanding the determinants of learner engagement in MOOCs: An adaptive structuration perspective. Comput. Educ. 2020, 157, 103963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, K.F. Promoting engagement in online courses: What strategies can we learn from three highly rated MOOCS. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 47, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergdahl, N.; Nouri, J.; Fors, U.; Knutsson, O. Engagement, disengagement and performance when learning with technologies in upper secondary school. Comput. Educ. 2020, 149, 103783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Gao, W.; Sha, J. Perceived Teacher Autonomy Support and School Engagement of Tibetan Students in Elementary and Middle Schools: Mediating Effect of Self-Efficacy and Academic Emotions. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Li, H.; Kornhaber, M.L.; Suen, H.K.; Pursel, B.; Goins, D.D. Examining the relations among student motivation, engagement, and retention in a MOOC: A structural equation modeling approach. Glob. Educ. Rev. 2015, 2, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Oraif, I.; Elyas, T. The Impact of COVID-19 on Learning: Investigating EFL Learners’ Engagement in Online Courses in Saudi Arabia. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnesia, R.H. Features Affecting Task-Motivation in English for Academic Purposes Online Learning. Second. Lang. Stud. 2010, 29, 1–34. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/40707 (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Reeve, J. How students create motivationally supportive learning environments for themselves: The concept of agentic engagement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, R.; Irby, T.L.; Wynn, J.T.; McClure, M.M. Investigating Students’ Satisfaction with eLearning Courses: The Effect of Learning Environment and Social Presence. J. Agric. Educ. 2012, 53, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, I.F.; Chen, M.C.; Sun, Y.S.; Wible, D.; Kuo, C.H. Extending the TAM model to explore the factors that affect Intention to Use an Online Learning Community. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.J.; So, H.J.; Kim, N.H. Examination of relationships among students’ self-determination, technology acceptance, satisfaction, and continuance intention to use K-MOOCS. Comput. Educ. 2018, 122, 160–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Liao, H.L.; Pratt, J.A. Impact of media richness and flow on e-learning technology acceptance. Comput. Educ. 2009, 52, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørebø, Ø.; Halvari, H.; Gulli, V.F.; Kristiansen, R. The role of self-determination theory in explaining teachers’ motivation to continue to use e-learning technology. Comput. Educ. 2009, 53, 1177–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing, 2nd ed.; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Market. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, X. Modeling the intention to use machine translation for student translators: An extension of Technology Acceptance Model. Comput. Educ. 2019, 133, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equations models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.F.; Trinidad, S.G. Using Web-based distance learning to reduce cultural distance. J. Interact. Online Learn. 2004, 3, 1541–4914. Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/p/158287/ (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Eseryel, D.; Law, V.; Ifenthaler, D.; Ge, X.; Miller, R. An investigation of the interrelationships between motivation, engagement, and complex problem solving in game-based learning. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2014, 17, 42–53. Available online: http://www.ifets.info/download_pdf.php?j_id=62&a_id=1432 (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Aguilera-Hermida, A.P. College students’ use and acceptance of emergency online learning due to COVID-19. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2020, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 137 (58.8) |

| Male | 96 (41.2) | |

| Educational level | Senior 1 | 86 (36.9) |

| Senior 2 | 124 (53.2) | |

| Senior 3 | 23 (9.9) | |

| Duration in synchronous online English courses | <2 weeks | 2 (0.9) |

| About 3 weeks | 1 (0.4) | |

| About 1 month | 20 (8.6) | |

| About 2 months | 126 (54.1) | |

| >2 months | 84 (36.1) |

| Constructs | Mean | Standard Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | 3.891 | 0.659 | −0.308 | 0.147 |

| Competence | 3.453 | 0.795 | −0.181 | 0.500 |

| Relatedness | 3.922 | 0.657 | −0.477 | 1.197 |

| Behavioral intention | 3.319 | 0.902 | −0.373 | 0.271 |

| Behavioral engagement | 3.691 | 0.763 | −0.297 | 0.184 |

| Cognitive engagement | 3.608 | 0.740 | −0.307 | 0.771 |

| Emotional engagement | 3.508 | 0.762 | −0.502 | 0.852 |

| Social engagement | 3.681 | 0.693 | −0.176 | 0.074 |

| Constructs | Indicators | Factor Loadings | AVE | Composite Reliability | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUTO | Auto1 | 0.717 | 0.673 | 0.860 | 0.754 |

| Auto2 | 0.886 | ||||

| Auto3 | 0.848 | ||||

| BE | BE1 | 0.810 | 0.749 | 0.899 | 0.831 |

| BE2 | 0.875 | ||||

| BE3 | 0.908 | ||||

| CE | CE1 | 0.873 | 0.714 | 0.882 | 0.799 |

| CE2 | 0.868 | ||||

| CE3 | 0.792 | ||||

| Comp | Comp1 | 0.847 | 0.707 | 0.879 | 0.793 |

| Comp2 | 0.829 | ||||

| Comp3 | 0.847 | ||||

| EE | EE1 | 0.857 | 0.673 | 0.891 | 0.838 |

| EE2 | 0.868 | ||||

| EE3 | 0.767 | ||||

| EE4 | 0.785 | ||||

| Relat | Relat1 | 0.877 | 0.677 | 0.862 | 0.757 |

| Relat2 | 0.730 | ||||

| Relat3 | 0.853 | ||||

| SE | SE1 | 0.712 | 0.620 | 0.867 | 0.795 |

| SE2 | 0.807 | ||||

| SE3 | 0.831 | ||||

| SE4 | 0.795 | ||||

| BI | BI1 | 0.764 | 0.729 | 0.889 | 0.814 |

| BI2 | 0.906 | ||||

| BI3 | 0.885 |

| AVE | AUTO | BE | CE | Comp | EE | Relat | SE | UI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUTO | 0.673 | 0.820 | |||||||

| BE | 0.749 | 0.736 | 0.865 | ||||||

| CE | 0.714 | 0.755 | 0.767 | 0.845 | |||||

| Comp | 0.707 | 0.659 | 0.692 | 0.809 | 0.841 | ||||

| EE | 0.673 | 0.682 | 0.711 | 0.794 | 0.745 | 0.820 | |||

| Relat | 0.677 | 0.567 | 0.630 | 0.496 | 0.468 | 0.492 | 0.823 | ||

| SE | 0.620 | 0.720 | 0.711 | 0.766 | 0.757 | 0.769 | 0.621 | 0.788 | |

| BI | 0.729 | 0.470 | 0.477 | 0.620 | 0.588 | 0.693 | 0.251 | 0.566 | 0.854 |

| Hypothesis | Path | β | t-Value | Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Autonomy—BE | 0.373 | 4.520 | Yes |

| H1b | Autonomy—CE | 0.381 | 5.691 | Yes |

| H1c | Autonomy—EE | 0.300 | 2.546 | Yes |

| H1d | Autonomy—SE | 0.278 | 3.003 | Yes |

| H2a | Competence—BE | 0.320 | 4.293 | Yes |

| H2b | Competence—CE | 0.547 | 8.870 | Yes |

| H2c | Competence—EE | 0.508 | 4.932 | Yes |

| H2d | Competence—SE | 0.456 | 6.276 | Yes |

| H3a | Relatedness—BE | 0.269 | 4.214 | Yes |

| H3b | Relatedness—CE | 0.023 | 0.441 | No |

| H3c | Relatedness—EE | 0.084 | 1.232 | No |

| H3d | Relatedness—SE | 0.250 | 3.054 | Yes |

| H4a | BE—BI | −0.150 | 1.548 | No |

| H4b | CE—BI | 0.251 | 2.268 | Yes |

| H4c | EE—BI | 0.566 | 5.499 | Yes |

| H4d | SE—BI | 0.046 | 0.458 | No |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, S.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, Y. Impact of Teenage EFL Learners’ Psychological Needs on Learning Engagement and Behavioral Intention in Synchronous Online English Courses. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710468

Zhou S, Zhu H, Zhou Y. Impact of Teenage EFL Learners’ Psychological Needs on Learning Engagement and Behavioral Intention in Synchronous Online English Courses. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):10468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710468

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Sijing, Huiling Zhu, and Yu Zhou. 2022. "Impact of Teenage EFL Learners’ Psychological Needs on Learning Engagement and Behavioral Intention in Synchronous Online English Courses" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 10468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710468

APA StyleZhou, S., Zhu, H., & Zhou, Y. (2022). Impact of Teenage EFL Learners’ Psychological Needs on Learning Engagement and Behavioral Intention in Synchronous Online English Courses. Sustainability, 14(17), 10468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710468