Preschool Federations as a Strategy for the Sustainable Development of Early Childhood Education in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Preschool Federations in the World

1.2. Preschool Federations in China

1.3. Effectiveness Evaluation of School Federations

1.4. The Current Study

- What are the features of preschool federations in Shanghai?

- What is the effectiveness of preschool federations perceived by the different stakeholders?

2. Methods

2.1. Document Analysis

2.2. Survey Study

2.2.1. Survey Participants

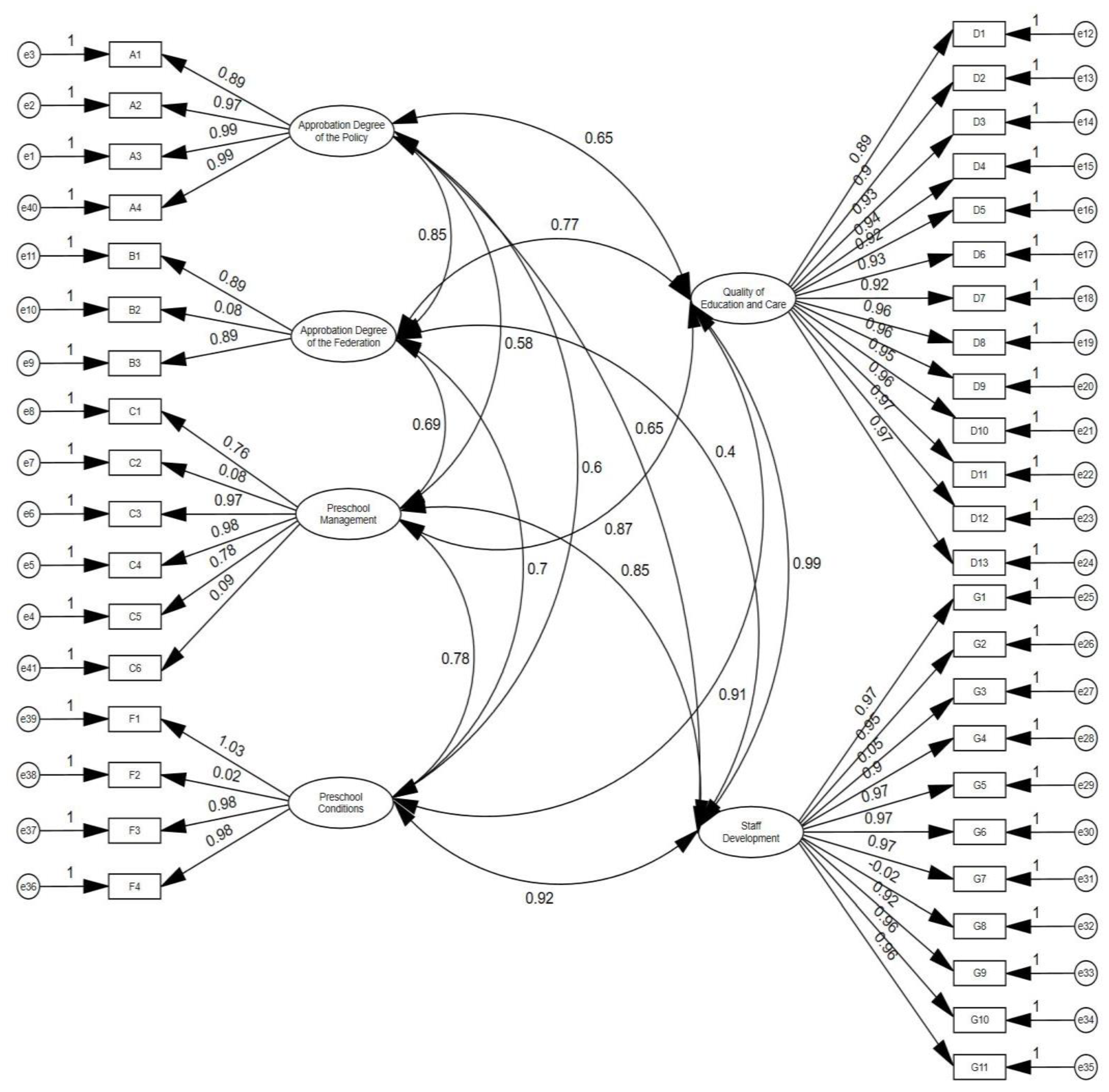

2.2.2. Measurement

2.3. Interview Study

2.3.1. Interview Participants

2.3.2. Interview Protocol

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis Plan

3. Results

3.1. Features of Preschool Federations in Shanghai

3.2. Stakeholder’s Approbation Degree of Preschool Federations

3.2.1. Overall Approbation Degree of Preschool Federations

3.2.2. Differences in the Approbation Degree

3.3. Stakeholder’s Evaluation of Preschool Federation Effectiveness

3.3.1. Overall Evaluation of Preschool Federation Effectiveness

3.3.2. Differences in the Overall Evaluation

4. Discussion

4.1. Features of Preschool Federations in Shanghai

4.2. Approbation Degree of Preschool Federations in Shanghai

4.3. Effectiveness and Sustainability of Preschool Federation in Shanghai

5. Political and Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- List of government documents analyzed in this study

| Date | Issuing Organization | Policy |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Ministry of Education | Opinions on Further Expanding Education Financing Channels and Speeding up the Development of Education |

| 2005 | Ministry of Education | Opinions on Further Promoting the Balanced Development of Compulsory Education |

| 2010 | Ministry of Education | Several Opinions of the State Council on the Current Development of Preschool Education |

| 2012 | Ministry of Education | Opinions on further promoting the Balanced Development of compulsory education |

| 2015 | Shanghai Municipal Education Commission | Implementing Opinion on Promoting Quality and Balanced Development of Education, District School Running and Group School Running |

| 2016 | Shanghai Pudong Education Bureau | Implementation Plan for Promoting School Districts and Groups in Pudong New Area |

| 2016 | Shanghai Changning Education Bureau | Guidelines on Promoting District school Running and Group School Running |

| 2016 | Shanghai Hongkou Education Bureau | Implementing Opinion on Promoting Quality and Balanced Development of Education, District school running and Group school running |

| 2017 | Shanghai Hongkou Education Bureau | Implementation Opinions on Comprehensively and Deeply Promoting District School Running and Group School Running of Hongkou District |

| 2017 | Ministry of Education | Opinions on the Implementation of the Three-Year Action Plan for the Third Phase of Preschool Education |

| 2017 | Shanghai Yangpu Education Bureau | Implementation Opinions on Promoting Group School Running in Yangpu District |

| 2017 | Shanghai Baoshan Education Bureau | The 13th Five-Year Plan for Education Reform and Development in Baoshan District |

| 2018 | Ministry of Education | Opinions of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council on Deepening the Reform and Standardizing the Development of Preschool Education |

| 2019 | Shanghai Municipal Education Commission | Shanghai Three-Year Action Plan for Pre-school Education |

| 2019 | Shanghai Municipal Education Commission | Implementation Opinions on Promoting the Construction of Shanghai Tightly-knit School Districts and Groups |

| 2019 | Shanghai Yangpu Education Bureau | Implementation Opinions on Promoting the Construction of Tightly-knit Group |

| 2019 | Shanghai Chongming Education Bureau | Implementation measures to Promote the Construction of Tightly-knit School Districts and Groups |

| 2020 | Shanghai Xuhui Education Bureau | Shanghai Three-Year Action Plan for Pre-school Education (2020–2022) |

| 2020 | Shanghai Hongkou Education Bureau | Implementation Opinions on Promoting the Construction of Shanghai Hongkou Tightly-knit School Districts and Groups |

| 2021 | Shanghai Huangpu Education Bureau | Key Points of Education in Shanghai Huangpu District in 2021 |

| 2021 | Shanghai Fengxian Education Bureau | Implementation Opinions on Promoting the School Running Mode of Joint Schools |

Appendix B

- The Shanghai preschool federations evaluation survey (SPFES)

| Subscale | Items (English) | Items (Chinese) |

|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder’s Approbation Degree of Preschool Federations (αapprobation = 0.881) Approbation Degree of the Policy | ||

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| Approbation Degree of the Federation | ||

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| Stakeholder’s Evaluation of Preschool Federation Effectiveness (αeffectiveness = 0.968) | ||

| Preschool Management | ||

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| Quality of Education and Care | ||

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| Staff Development | ||

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| Preschool Conditions | ||

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Appendix C

Appendix C.1

- Based on what background and consideration did you initially start implementing preschool federations?

- What is the history of the preschool federations?

- What is the management mechanism of the district school federations running?

- How does the integrated management and operation mechanism of the Education Group work?

- How does the project leading mechanism promote the growth of the preschool education management organization?

- Can you give a detailed introduction to the teacher mobility mechanism, including the three-level mobility mechanism, the flexible mobility mechanism, and the teachers as navigators, and how effective they are?

- What measures has our district taken to promote curriculum sharing between schools and curriculum innovation, and what are the current results?

- How to assess the performance of the school federations?

- What achievements have been made in the 5 years of school federations running? Where has it changed the most?

- In the process of running school federations, what experiences do you think are worth promoting?

- What problems have you encountered in the process of running school federations, and how did you solve them?

- Are there any side effects of school federations? What are the new challenges facing school federations? How will follow-up policies develop?

Appendix C.2

- What was your initial consideration for joining preschool federations? Can you give a detailed introduction to the preschool federations -running model?

- Your attitude and understanding of the group-based school-running policy?

- What achievements have the Education management organization achieved so far? Where has it changed the most?

- How does the management mechanism within the group operate (such as management, teachers, courses, preschool-family collaboration, etc.)

- How does the Education management organization avoid the “overwhelming” of the core preschools and the “homogenization” of member preschools to achieve a true sharing and win-win situation?

- What experiences are worth promoting in the school federations running? What problems did you encounter? How was it resolved?

- What are the new challenges currently faced in the process of school federations? What policy support do you expect to receive, and what are your expectations for the future planning or development of the Organization?

Appendix C.3

- What changes can you feel after the preschool federations? What do you think is the biggest change?

- What reform measures have you seen in running preschool federations, and which aspect of reform do you pay most attention to? Why?

- What activities have you participated in within the education management organization? What have you gained, and what difficulties have you encountered?

- How do you view the preschool federations?

- As a teacher, what are you confused about preschool federations? What kind of support would you like to receive in your follow-up career development?

Appendix C.4

- Do you know the current policy of group preschools running in Shanghai? Do you want your child’s preschool to join the federation? Why is that?

- What improvements have been made in the quality and education conditions of your child’s preschool after participating in a federation?

- What measures have been taken by your child’s preschool to promote preschool-family cooperation after participating in a federation?

- What do you think has improved the most due to your child’s preschool being part of a federation? Where is it reflected?

- What aspect of reform are you most concerned about in the group school? Why?

- What problems and challenges do you think exist in group school running? As a parent, what are your expectations for the future of the federation?

References

- Chapman, C.; Muijs, D. Does school-to-school collaboration promote school improvement? A study of the impact of school federations on student outcomes. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2014, 25, 351–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, C. From one school to many: Reflections on the impact and nature of school federations and chains in England. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2015, 43, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B. School cluster development: Theoretical breakthroughs and practice choices. J. Educ. Stud. 2019, 15, 43–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Opinions on Further Promoting the Balanced Development of Compulsory Education; Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2005. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A06/s3321/200505/t20050525_81809.html (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- The State Council of China. Opinions on Promoting Quality and Balanced Development of Compulsory Education; The State Council of China: Beijing, China, 2012. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhuanti/2015-06/13/content_2878998.htm (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Li, H.; Yang, W.; Chen, J.J. From ‘Cinderella’ to ‘Beloved Princess’: The Evolution of Early Childhood Education Policy in China. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy 2016, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Li, H. Accessibility, affordability, accountability, sustainability and social justice of early childhood education in China: A case study of Shenzhen. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanghai Municipal Education Commission. Implementing Opinion on Promoting Quality and Balanced Development of Education, District School Running and Group School Running; Shanghai Municipal Education Commission: Shanghai, China, 2015. Available online: http://www.shanghai.gov.cn/nw12344/20200814/0001-12344_45561.html (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Li, H.; Wang, D.; Fong, R.W. Introduction: Sound bites won’t work: Case studies of 15-year free education in Greater China. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 2014, 3, 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Park, E.; Chen, J.J. Preface: From ‘Sound Bites’ to Sound Solutions: Advancing the Policies for Better Early Childhood Education in Asia Pacific. Early Childhood Education Policies in Asia Pacific: Advances in Theory and Practice; Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns, and Prospects; Springer: Singapore, 2017; Volume 35, pp. vii–xiii. [Google Scholar]

- Muijs, D.; West, M.; Ainscow, M. Why network? Theoretical perspectives on networking. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2010, 21, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T. The Practical Research on Group Education in the Area from the Perspective of the Balanced Development of Compulsory Education. Master’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.H. Brief analysis on the development and operation of foreign education group. Open Educ. Res. 2002, 2, 8–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tooley, J.; Corporation, I.F. The Global Education Industry: Lessons from Private Education in Developing Countries; IEA Studies in Education; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C. Research on the Implementation Effect of Group-School Running in County Area. Master’s Thesis, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.S. A Study on the Problems and the Countermeasures of Running a Public Preschool Group: A Case Study of Shenzhen Longgang Early Childhood Education Group. Master’s Thesis, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China, 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L. Research on the Mechanism of Sharing Quality Resources in Preschool Education under the Grouping Model. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, F. Education Industry Offers World of Investment Opportunity. Ventur. Cap. J. 2001, 3, 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. The evolution and inspiration of government responsibility boundary in the development of preschool education in the 40 years of reform and opening up. J. Chin. Soc. Educ. 2019, 40, 37–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, J.Z. Management and Practice of Preschool Group; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2014; pp. 6–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ke, C.Y. Implement group preschool running and promote the high-quality and balanced development of preschool education. Pop. Sci. 2011, 75, 103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.Y. Analysis and Reflection on the process of group school running. Early Educ. 2009, 27, 36–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Jinshan District Education Bureau. Implementation Opinions on the Third Round of Group Development of Preschool in Jinshan District; Shanghai Jinshan District Education Bureau: Shanghai, China, 2019. Available online: http://www.jinshan.gov.cn/jyj-jyggfzzdgz/20200825/771717.html (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Muijs, D. Improving schools through collaboration: A mixed methods study of school-to-school partnerships in the primary sector. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2015, 41, 563–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, P.W.; Brown, C.; Chapman, C.J. School-to-school collaboration in England: A configurative review of the empirical evidence. Rev. Educ. 2021, 9, 319–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.L. Research on the Problems of Education Group Development. Master’s Thesis, Minzu University of China, Beijing, China, 2012. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F.; Jiang, X.J. Let more children enjoy better education-Exclusive interview with Shao Zhiyong, director of Education Bureau of Yangpu District. Shanghai Educ. 2015, 59, 23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.Q.; Liu, P.Q. On practice and reflection of running school by group in Beijing Haidian district. Educ. Res. 2018, 39, 154–159. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, F.C. Inter-school cooperation dilemma in the grouped school-running: Internal mechanism and resolution path—Based on organizational boundary angle of view. Educ. Res. 2018, 39, 87–97. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Building education groups as school collaboration for education improvement: A case study of stakeholder interactions in District A of Chengdu. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2021, 22, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Xu, L.; Sun, C.R. Evaluation of the effectiveness of preschool federation after entering a new stage and exploration of the paths—A study based on the perception of 7655 cadres and teachers of preschool federation in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province. Prim. Second. Sch. Manag. 2021, 35, 26–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, J. Relationship between effectiveness of specific links of grouped school running and its overall effect. Theory Pract. Contemp. Educ. 2022, 14, 99–106. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón-Piqueras, J.Á.; Prieto-Ayuso, A.; Gomez-Moreno, E.; Martinez-Lopez, M.; Gil-Madrona, P. Evaluation of a Program of Aquatic Motor Games in the Improvement of Motor Competence in Children from 4 to 5 Years Old. Children 2022, 9, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.F.; Han, Y.M. International trends and methodological implications of education policy evaluation studies: An interview with professor Yan Wenfan. J. Soochow Univ. Educ. Sci. Ed. 2020, 8, 76–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Sánchez, M.B.; Gil-Madrona, P.; Martínez-López, M. Psychomotor development and its link with motivation to learn and academic performance in Early Childhood Education. Rev. Educ. 2021, 392, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Municipal Education Commission. Implementing Opinion on Promoting Construction of Close-Knit School Districts and Groups in Shanghai; Shanghai Municipal Education Commission: Shanghai, China, 2019. Available online: http://edu.sh.gov.cn/shgy_ywjy_gz_1/20210414/e37567943e9a46cfa31f456aaaa0b228.html (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Wang, X.T. Existing problems in collectivized running of basic education and their resolutions. J. Teach. Manag 2021, 38, 8–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, C.C. A Case Study of Group Education in Primary Education from the Perspective of Stakeholders. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, China, 2017. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.B. A practical exploration of collectivized kindergarten management. J. Ningbo Inst. Educ. 2017, 19, 109–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.C. The recognition of quality and balanced compulsory education from the perspective of educators. Mod. Educ. Manag. 2019, 39, 43–49. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.L. Study on the Effectiveness Evaluation of Compulsory Education Collectivization School-Running: Taking Single-Legal-Person Federations in Shanghai J District as an Example. Master’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H.Q.; Jia, J.E. The multiple participants and their complement in education governance. Res. Educ. Dev. 2014, 34, 1–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Categories | Role | N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preschool Leaders | Teachers | Parents | |||

| Educational attainment | High school diploma and below | 0 | 0 | 14 | 14 (2%) |

| Associate’s degree | 1 | 24 | 52 | 77 (11%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 51 | 277 | 223 | 551 (79%) | |

| Master’s degree | 2 | 8 | 47 | 57 (8%) | |

| Doctorate degree | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 (1%) | |

| Nature of preschool | Public | 52 | 301 | 335 | 688 (98%) |

| Private | 2 | 8 | 4 | 14 (2%) | |

| Preschool level 1 | Unrated preschool | 5 | 22 | 5 | 32 (5%) |

| Second-level preschool | 0 | 6 | 16 | 22 (3%) | |

| First-level preschool | 36 | 191 | 195 | 422 (60%) | |

| Model preschool | 13 | 90 | 123 | 226 (32%) | |

| Characteristics | Categories | Educational Attainment | N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Associate’s Degree | Bachelor’s Degree | Master’s Degree | |||

| Nature of preschool | Public | 19 | 118 | 1 | 138 (98%) |

| Private | 1 | 6 | 1 | 8 (2%) | |

| Preschool level | Unrated preschool | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 (3%) |

| Second-level preschool | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (1%) | |

| First-level preschool | 9 | 66 | 1 | 76 (52%) | |

| Model preschool | 9 | 55 | 1 | 65 (44%) | |

| Factor | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|

| Factor1 | 0.9786 | 0.9197 |

| Factor2 | 0.7069 | 0.5255 |

| Factor3 | 0.8221 | 0.5165 |

| Factor4 | 0.9896 | 0.8802 |

| Factor5 | 0.9631 | 0.7419 |

| Interviewee | Affiliation | Position | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | Preschool Education Department | Government official | Male |

| L2 | Educational Development Institute | Government official | Male |

| W | Preschool Education Department | Government official | Female |

| S | P Federation | Principal of a preschool | Female |

| H1 | D Federation | Principal of a preschool | Female |

| Z | Z1 Federation | Principal of a preschool | Female |

| L | P Federation | Head of the Teaching and Research Section | Female |

| T | D Federation | Teacher in a core preschool | Female |

| X | N Federation | Teacher in a core preschool | Female |

| Y | N Federation | Teacher in a core preschool | Female |

| H2 | R Federation | Teacher in a member preschool | Female |

| X2 | Z2 Federation | Teacher in a member preschool | Female |

| C | S Federation | Teacher in a member preschool | Female |

| R | P Federation | Parents | Female |

| F | S Federation | Parents | Female |

| Dimensions | Total Number of Reference Points for Each Dimension (%) | Tree Node under Each Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| Government guidance and federation autonomy | 76 (27%) |

|

| Running model of preschool federation | 18 (7%) |

|

| The feature of each district | 183 (66%) |

|

| Dimensions | Total Number of Reference Points for Each Dimension (%) | Tree Node under Each Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| Approbation degree of the policy | 46 (12%) |

|

| Approbation degree of the federation | 33 (9%) |

|

| Preschool management | 71 (19%) |

|

| Staff development | 87 (23%) |

|

| Quality of education and care | 114 (30%) |

|

| Preschool conditions | 25 (7%) |

|

| Dimension | Leader M (S.D.) | Teacher M (S.D.) | Parents M (S.D.) | F | η2 | LSD 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall approbation degree | 4.49 ± 0.64 | 4.33 ± 0.70 | 3.90 ± 0.61 | 42.91 *** | 0.327 | 1 > 2 > 3 |

| Approbation degree of the policy | 4.61 ± 0.74 | 4.53 ± 0.85 | 4.05 ± 0.75 | 35.07 *** | 0.220 | 1 > 3; 2 > 3 |

| Approbation degree of the preschool federation | 4.37 ± 0.66 | 4.13 ± 0.74 | 3.76 ± 0.71 | 33.83 *** | 0.139 | 1 > 3; 2 > 3 |

| Dimension | Leader M (S.D.) | Teacher M (S.D.) | Parents M (S.D.) | F | η2 | LSD 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall effectiveness evaluation | 4.26 ± 0.50 | 4.24 ± 0.62 | 4.10 ± 0.60 | 61.03 *** | 0.950 | 1 > 2 > 3 |

| Preschool management | 4.64 ± 0.58 | 4.55 ± 0.70 | 4.38 ± 0.64 | 7.09 *** | 0.084 | 1 > 3; 2 > 3 |

| Quality of education and care | 4.32 ± 0.57 | 4.25 ± 0.66 | 4.11 ± 0.59 | 5.83 ** | 0.041 | 1 > 3; 2 > 3 |

| Staff development | 4.47 ± 0.56 | 4.36 ± 0.67 | 4.15 ± 0.63 | 11.48 *** | 0.454 | 1 > 3; 2 > 3 |

| Preschool conditions | 3.61 ± 0.40 | 3.79 ± 0.49 | 4.07 ± 0.71 | 25.80 *** | 0.826 | 3 > 1; 3 > 2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, J.; Zhang, J.; Bai, Y.; Li, H.; Xie, S. Preschool Federations as a Strategy for the Sustainable Development of Early Childhood Education in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9991. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169991

Fang J, Zhang J, Bai Y, Li H, Xie S. Preschool Federations as a Strategy for the Sustainable Development of Early Childhood Education in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):9991. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169991

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Junjun, Jun Zhang, Yingxin Bai, Hui Li, and Sha Xie. 2022. "Preschool Federations as a Strategy for the Sustainable Development of Early Childhood Education in China" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 9991. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169991

APA StyleFang, J., Zhang, J., Bai, Y., Li, H., & Xie, S. (2022). Preschool Federations as a Strategy for the Sustainable Development of Early Childhood Education in China. Sustainability, 14(16), 9991. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169991