1. Introduction

Last-mile delivery systems have increasingly exploited the use of drones in a number of applications to reduce delivery times, avoid traffic delays and potentially cut costs in the long term [

1,

2,

3]. The actual implementation of fully drone-based last-mile solutions is challenged by the intrinsic characteristics of drones as small payload and limited battery capacity. Amazon released a number of patents trying to address these issues, envisioning multilevel fulfillment centers, also called Beehives (BHs), providing a number of services from package handling to recharging/refueling operations. These stations raise emerging problems relative to the management of the delivery services provided and the shared used of these big, capital intensive facilities. In this setting, each drone does not need to return to the departure depot for reloading and battery charging, but it can fly to other depots, enabling the shift from independent business operations to collaboration. Sharing BHs could sensibly reduce the total number of drones in the sky and the total operational costs of companies, but raises operational challenges to be addressed.

Although the idea of sharing BHs seems quite appealing, there are only a very few studies addressing the operational challenges in the last-mile drone delivery with sharing BHs. The distinguished study of Aurambout et al. [

4] presents a framework to estimate the economic viability of potential drone BH locations across the European cities. Recently, Bruni. and Khodaparasti. [

5] provided a mathematical programming approach for this complicated problem, considering some realistic features as drone energy consumption rates—which non-linearly depends on the payload, frame and battery mass, and travel time—and uncertainty in flight duration. We should mention that the model is quite involved, since it takes into account the non-linear nature of the energy constraints.

To the best of our knowledge, there are only a few studies that explicitly account for the energy constraints with non-linear rates [

1,

6]. They model the energy consumption rate in drone battery as a non-linear function in terms of payload and linear in terms of the travel time. However, a linear approximation approach is adopted to avoid the computational burden of dealing with non-linear energy constraints.

On the other hand, other studies replace the energy constraints with the more tractable flight range constraints to implicitly account for the limited drone battery charge [

7].

The current paper aimed to fill this potential gap. In particular, we are interested in the development of efficient solution methods for the Drone Routing Problem with Shared BHs (DRP-ShaBH) [

5]. We propose a tailored matheuristic approach that combines the Variable Neighborhood Descent (VND) [

8], a metaheuristic commonly used as a local search for the Variable Neighborhood Search, with a cut generation procedure. The integration of VND presents numerous success cases in the literature but it must be carefully designed, since the computational cost of local search operators might compromise the entire optimization strategy.

The contributions of the paper is twofold:

We formulate the drone delivery with shared BHs as a location-routing mathematical model where the non-linear nature of energy consumption rates in drone battery and the uncertainty of flight duration are taken into account.

We develop an efficient matheuristic approach integrating the VND with a cut generation procedure that provides promising results outperforming the Gurobi off-the-shelf solver.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we review the relevant literature on drone-aided location-routing problems. In

Section 3, we describe the DRP-ShaBH and formulate it as a deterministic mathematical program. Next, we derive the robust counterpart of the model under the uncertainty of flight duration. In

Section 4, we describe the proposed matheuristic approach that tackles the computational complexity of the DRP-ShaBH exacerbated by the combined location and routing nature of the problem. In

Section 5, we report the computational experiments conducted on a set on benchmark instances. Finally, we conclude the paper in

Section 6 and outline avenues for future research.

2. Literature Review

In this section, we review the literature on drone location-routing problems in the last-mile delivery. We may recognize two different streams in the literature: (i) The contributions that adopt a hierarchical approach in which the location decisions and the operational drone-routing plans are tackled separately in a hierarchical fashion; (ii) the studies that address the strategic/tactical location plans and operational routing decisions simultaneously. As a matter of fact, the adoption of each stream is dependent on the application context.

Following the first stream, Kim et al. [

9] proposed a set covering model to find the optimal locations used as drone depots in a healthcare context, followed by a multi-depot drone pickup and delivery model that minimizes the cost of used drones. The model accounts for the drone payload and the maximum drone flight time. A preprocessing algorithm, a partition method and a lagrangian relaxation method were developed to solve the model. Torabbeigi et al. [

10] proposed two mathematical formulations involving strategic and operational plans to optimize the drone routes in a parcel delivery application. At the strategic level, a set covering model determines the minimum number of required depots to cover all customers, next, at the operational stage, a routing model is solved that finds the optimal drone routes minimizing the fleet size. The authors modeled the energy consumption as linear constraints where the consumption rates are expressed as a linear function of drone payload, drone mass, and travel time. The authors developed a variable preprocessing algorithm and a primal and dual bound generation procedure to accelerate the solution approach performance.

Following the second stream, Liu et al. [

11] proposed a location-routing model for a patrolling problem with drones to find the optimal location of drone launching bases and drone routes simultaneously. The aim is to minimize the total cost encompassing the base establishment cost, drone usage cost, and flight cost. The authors imposed some lower and upper bounds on the capacity of established bases and a maximum drone flight duration was considered to account for the limited battery charge. The authors developed two heuristic algorithms combined with local search that handles a test case with 25 target points and 5 potential base stations. In another study, Yakıcı [

12] proposed a selective location-routing problem that seeks the optimal location of drone stations and optimal drone tours with the aim of maximizing the sum of importance values corresponding to the covered interest points. The model accounts for a maximum flight time and an upper bound for the number of selected stations. As the solution method, an ant colony optimization metaheuristic is designed. Kim et al. [

7] proposed a drone routing model with multiple depots, multiple drones, allowing multiple UAVs to deliver goods to one customer at the same time. The objective function minimizes the delivery and drone usage costs. The drone payload capacity and a maximum flight distance are considered. The optimal location of selected depots, the fleet size, and the drone routes are the output of the problem. The model is solved for instances up to 75 customers. In another paper, Li et al. [

13] studied a multi-depot drone routing problem minimizing the total number of dispatched drones and the total travel distance. The model accounts for a maximum drone flight time. Since all the depots are not required to be used, the optimal location of used depots is an output of the problem. To solve the problem, the authors presented a heuristic approach based on hybrid large neighborhood search. In a recent paper, Grogan et al. [

14] addressed a drone application for relief operations after tornado. The authors presented a multi-depot routing problem to minimize the maximum route duration while imposing a maximum drone endurance limit for each drone. We classify the latter contribution as a location and fleet sizing model since the number of dispatched drones and occupied depots are the problem outputs.

To conclude, the energy consumption notion in the literature has been simplified or replaced by the flight range notion in order to avoid the computational burden caused by the non-linear energy constraints. This, clearly, makes the validity of the route plans and the BH site location decisions quite questionable. Moreover, the uncertainty and the fluctuations in the flight duration has not been addressed in the aforementioned studies. The current study bridges this gap and presents an efficient solution approach to handle the computational burden of a realistic model that explicitly accounts for complicating features such as the non-linear energy consumption rate in drone battery and the uncertain flight duration.

3. Drone Routing Problem with Shared Beehives

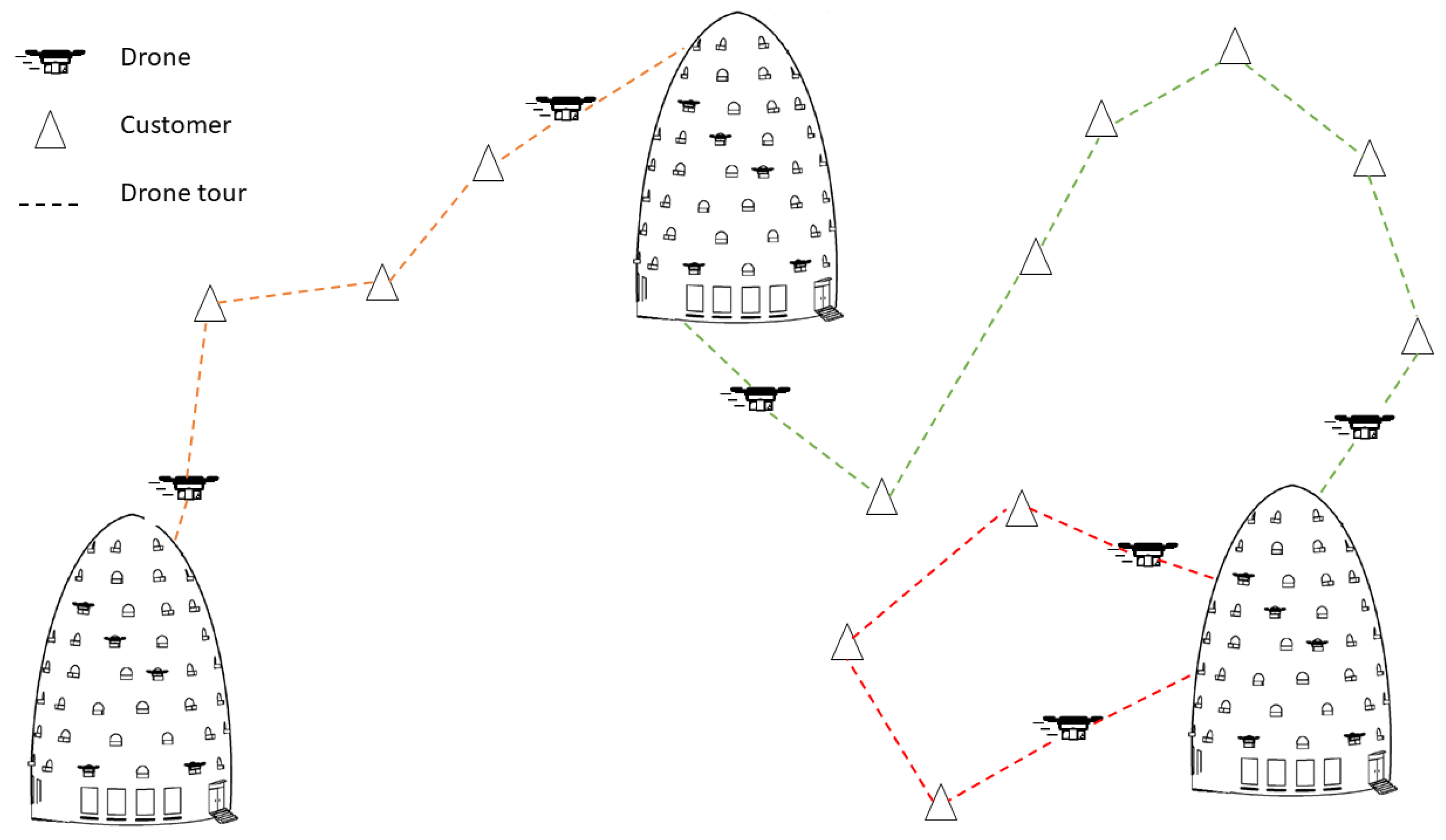

The DRP-ShaBH under the uncertainty of flight duration is a tailored location-routing problem, where the operational challenges related to the use of drones, among which energy consumption and the uncertainty in flight duration, are taken into account. We assume that a set D of distributed BHs are available as the drone stations to enhance last-mile delivery. We can consider any type of BHs, truck-based warehouses, local re-stocking stations for drones or fulfillment centers. The BHs offer landing, takeoff, package handling, and recharging services where each BH can host up to drones. A limited number of drones can shuttle back and forth between the BHs and a maximum number of BHs can be used. A retail company uses the drones to deliver orders from BHs to a set C of customers. Each drone performs a distinct tour started from a specific BH, where the drone is loaded with the customers’ orders up to its payload capacity Q. Next, the drone is launched to visit a subset of customers one by one. Upon arrival to each customer’s site, the drone leaves the order and flies to visit the next customer. After delivering the order of the last customer within its tour, the drone is retrieved at one of the selected BHs, that could be different from the BH we used to launch the drone.

Figure 1 represents the delivery scheme for the DRP-ShaBH.

Instead of assuming that drone endurance is limited by a fixed amount of distance, we consider energy consumption as a (non-linear) function of drone payload, frame and battery mass, and travel time.

In fact, Dorling et al. [

1] model the energy consumption based on the main assumption that the power consumed during takeoff, or landing is approximately equivalent to the power consumed while hovering and the thrust balances the weight force.

In particular, let

be the flight duration (travel time) between nodes

i and

j in the network,

(

W is the frame mass (in kg) and

M (in kg) is the battery mass). The drone energy consumption along arc

, while carrying a payload of

d is expressed as

where

(here,

g is the force applied by gravity per unit mass (in N/kg),

is the fluid density of air (in kg/m

),

is the area of spinning blade disc (in m

), and

h is the number of rotors) [

1].

The mathematical formulation of DRP-ShaBH is essentially developed based on the multi-layered network, which has been proved to be superior to other models, for a wide range of routing problems (for more information about the multi-layered network, please see [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]). The model takes the advantage of position-dependent binary variables:

which indicates if customer

is visited in position

r along the drone tour (meaning that customer

i is the

-last customer served by the drone within its trip),

to show that customer

is visited right after node

in position

r and

which tells if customer

is the first one to be visited by a drone launched from BH

and there are

customers left to be visited along the tour. Binary variable

indicates if BH

is used or not. The total load carried by the drone upon departure from customer

i to reach customer

j is denoted by

; if customer

j is the first customer after the drone departure from BH

f, its load is denoted by

. The accumulated energy consumption upon arrival at node

is denoted by

. Let

denote the set of auxiliary BHs introduced to specify the ending points of the drone trip and

be the set of positions where

Table A1 in

Appendix A summarizes the notation used in the mathematical formulation of the problem. The DRP-ShaBH is formulated as follows:

where

and

are “bigM” numbers and the variables definitions are as in

Table A1.

The objective function (1) represents the total waiting times of the customers. Constraints (2) ensure that each customer is visited exactly once. Constraint (3) ensures the use of exactly

drones. Constraints (4)–(6) guarantee the continuity of each tour. Constraints (7) force nodes to be connected to node 0 at level

N. Constraints (8) and (9) allow starting a drone route only from used facilities. Constraints (10) and (11) represent the restriction on the maximum number of BHs used and the number of drones that each BH can handle. Constraints (12) and (13) define the relation between the last customer visited and the destination BH. Constraints (14) determine the return of drones to BHs already used as drone launch sites. Constraints (15)–(19) are used to limit the drone payload [

20], while (20)–(23) represent the drone energy consumption. Finally, the set of constraints (24)–(33) establish the nature of the variables.

As is known, weather conditions, wind direction and aerial congestion can influence the travel time of the drone and, hence, the energy consumption. In this paper, we consider drone travel time between nodes

i and

j as an uncertain parameter denoted by

that belongs to a box uncertainty set

, where

is an adjustable parameter controlling the size of the uncertainty set. We refer the reader to [

21] for more information on uncertainty sets in robust optimization.

Following the robust paradigm in [

22], the robust counterpart of the DRP-ShaBH is expressed as follows.

where the uncertain parameter

falls within the symmetric box

.

Needless to say, the computational intractability of the model is exacerbated by the presence of non-linear constraints (35)–(37). To overcome this difficulty, we develop an efficient VND-based matheuristic which is discussed in

Section 4.

4. The VND-Based Matheuristic

In this section, we outline the proposed matheuristic integrating the VND heuristic with a cutting plane approach. The main idea behind the proposed VND-based Matheuristic (VND-M) is to apply VND as a local search heuristic that explores different neighborhood structures in a deterministic way. In particular, we define each neighborhood by constraints which are derived based on the last information on the current solution. To be more precise, we construct two types of constraints, known as “no-good” cuts, that exclude the current solution from the search space [

23].

To derive the cuts, we decompose the problem into a master problem ignoring the complicating non-linear energy constraints (35)–(37), and a subproblem that checks the feasibility of the current solution with respect to the energy constraints. The master problem is solved to optimality using an off-the-shelf MIP solver (such as Gurobi) and based on the information we get from the optimal solution, inequalities cutting off the current solution from the feasible space are added as constraints into the master problem. In the following, we explain how the inequalities are generated.

From now on, we call any feasible solution of the master problem that is also feasible for the subproblem an “energy-feasible” candidate.

Once the master problem is solved, an integer feasible solution with the corresponding objective value is found. Next, we evaluate the feasibility of solution p with respect to the subproblem (35)–(37). Two mutually exclusive cases may occur:

- (1)

The current solution

p is not an energy-feasible solution and the battery capacity for some of the drone tours is violated (we refer to the tours exceeding the battery charge as the “infeasible tours”). In this case, corresponding to each infeasible tour

in

p, a valid no-good cut (38) is generated and added to the master problem.

Note that is a pre-specified integer input parameter. From now on, we refer to (38) as the cut type I. Any cut in the form of (38) is, in fact, a valid cut that ensures corresponding to each infeasible tour , at least customers/BHs are removed. Obviously, the higher the value of is, the more emphasis on seeking diverse solutions is imposed. Once the cuts are generated, we can specify the structure of neighborhood as follows:

Let be the set of infeasible tours in p, the neighborhood is defined as where X denotes the master problem solution space. We should note that the parameter is interpreted as the size of neighborhood .

- (2)

The current solution

p is an energy-feasible solution, not necessarily optimal. Therefore, we cut off the current solution from the search space introducing a single no-good cut cut type II removing the current solution from the search space.

where

. The neighborhood

is defined as

.

Algorithm 1 describes the cut generation procedure. We should note that, each time the master problem is solved, we invoke a build route procedure to retrieve the routes

from

p. The scheme of the procedure is shown in Algorithm 2. Thanks to the build route procedure, the energy feasibility check of a master problem solution is easily done in polynomial time.

| Algorithm 1:Generate cut procedure |

- 1:

Input: Solution p - 2:

Output: Set of cuts - 3:

- 4:

- 5:

ifp is energy-feasible then - 6:

Generate type II cut as in (39) - 7:

- 8:

else - 9:

for (set of infeasible tours) do - 10:

Generate type I cut as in (38) - 11:

- 12:

end for - 13:

end if - 14:

Return

|

| Algorithm 2:Pseudocode of build route procedure |

- 1:

- 2:

for do - 3:

if then - 4:

- 5:

- 6:

- 7:

- 8:

repeat - 9:

- 10:

if then - 11:

- 12:

break - 13:

end if - 13:

- 15:

- 16:

until - 17:

- 18:

- 19:

end if - 20:

end for - 21:

Return

|

The general sketch of the VND-M method is shown is Algorithm 3. The algorithm takes the maximum number of neighborhoods to explore as the input which is denoted by and returns the incumbent with the corresponding objective value . First, in Line 4, the master problem is solved and an integer feasible solution p with objective value is found. Next, the feasibility subproblem is solved to check the energy feasibility of p. If p is energy feasible, the incumbent and its objective value are updated (Lines 5–7). Lines 8–27 describe the scheme of VND heuristic. Starting from the first neighborhood specified by its right hand side of in line 9, the corresponding neighborhood around p is explored; this requires the definition of the proper cut (Line 11) which is then added into the master problem (Line 12) which is solved again to find a new solution . Three different cases are relevant:

- (i)

The new solution is energy-feasible, therefore, we replace the current solution p with and update the incumbent, if necessary (Lines 13–17).

- (ii)

The new solution is not energy-feasible but the amount of violation is within an acceptable pre-specified threshold . In such case, we replace the current solution p with (Line 19). This can be regarded as a diversification mechanism to allow a controlled exploration of infeasible promising solutions.

- (iii)

None of the two previous cases holds. Hence, we move to the next neighborhood (Line 21).

This procedure is repeated until all the

neighborhoods are explored. We also keep track of the incumbent updates to early end the algorithm whenever no improving solution within the last

consecutive iterations is found. As for the stopping criterion, a time limit is imposed.

| Algorithm 3:VND-M |

- 1:

Input: - 2:

Output: - 3:

Initialization: - 4:

Find an integer feasible solution p for the master problem - 5:

if p is energy feasible then - 6:

- 7:

end if - 8:

while not stopping criterion do - 9:

- 10:

while do - 11:

Generate cut (p) - 12:

Solve the master problem with cuts and let be the optimal solution - 13:

if is energy-feasible then - 14:

- 15:

if then - 16:

- 17:

end if - 18:

else if energy-violation is within a predefined threshold then - 19:

- 20:

else - 21:

- 22:

end if - 23:

if No improvement within the last consecutive iterations then - 24:

break - 25:

end if - 26:

end while - 27:

end while - 28:

Return

|

5. Computational Experiments

In this section, we report on the computational study carried out to assess the validity of the proposed matheuristic approach. All the experiments were executed on an Intel Core i7-10750H, with GHz CPU and 16 GB RAM working under Windows 10. The model and the VND-M algorithm were implemented in the algebraic modeling language AIMMS . Since model (34)–(37), (2)–(19), (23)–(33), is a non-linear MIP model, we solved it using the AIMMS Outer Approximation (AOA) algorithm. Gurobi 9.0.1 was used instead to solve the master problem. A time limit of 500 s was set for both the exact and the matheuristic approach.

We adopted the set of A1 instances up to 40 customers from [

6]. The coordinates of the customer are the same as those reported in [

6]. Regarding the customer demand, we considered a random demand distribution varying between

kg for the first

of customers and

kg for the rest of customer. We considered up to 5 potential BHs with two spatial configurations (close to the center of the delivery area or in the outskirts), referred to as centered and marginal. In the problem analysis, values of

were set as the maximum number of drones per BH, depending on the problem size. Finally, we considered a homogeneous fleet of

or 8 Alta 8 drones with the following characteristics:

W = 6.2 (kg),

M = 2.8 (kg),

Q = 9.1 (kg),

h = 8, ρ = 1.204 (kg/m

3),

As for the heuristic, we set the following input values

.

Table 1 and

Table 2 report the computational results under the centered and marginal configurations, respectively. Columns 1–5 present the characteristic of the instances considered; the objective function value (Obj) and the solution time in seconds (CPU) for both the proposed VND-M and the AOA are reported in columns 6–7 and 8–9, respectively. Column 10 with heading LB displays a lower bound derived from a linear relaxation of the master problem where all the integer variables except the

variables are relaxed. Needless to say that the lower bounds for cases solved to optimality are not relevant and therefore have not been reported. Finally, the last column with heading

represents the relative gap (in percentage) with respect to the solution found by AOA, if any; otherwise, the gap has been calculated with respect to the lower bounds LB.

As the results show, AOA provides the optimal solution for instances up to 20 customers. As a general observation, we note that the AOA computational time is also quite limited, especially considering that this problem is a tactical operational problem. Interestingly, for all instances solved to optimality by AOA, the VND-M finds the optimal solution, too (except for instance A1-15-5 with the centered configuration for which the optimality gap is quite low ). In terms of the solution time, for the smallest instances with 10 customers, the VND-M CPU time is higher than the AOA’s but with the increase of instance size to 15 and 20, the VND-M CPU time outperforms the AOA significantly. For instances with more than 30 customers, the AOA fails to find any feasible solution within the time limit (those specified by TL that accounts for Time Limit). On the contrary, the proposed VND-M is quite fast and reports promising results for all instances confirmed by the average gap of at most and and the CPU time of and s under the centered and marginal configurations, respectively.

The position of the BHs does not seem to influence a lot the total latency since on average the percentage difference is quite low and below .

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have computationally addressed a new emerging problem in drone-aided last-mile logistics modeled as a variant of the location-routing problem, called DRP-ShaBH. The main characteristics of this new problem are the drones intrinsic properties, as the limited battery capacity, payload, and the weather-related uncertainties that lead to uncertain flight duration.

The model introduced can be solved to optimality for instances with limited size up to 20 customers. For larger instances, we have proposed a matheuristic approach based on a variable neighborhood descent heuristic and cutting planes. The efficiency of the proposed solution approach is investigated on instances with up to 40 customers.

There are several fruitful directions for future research based on the present study. To have a clear idea about the solution approach efficiency, we may investigate the performance of the proposed matheuristic compared with the state-of-the-art metaheuristics especially for large instances. In addition, it would be interesting to study the DRP-ShaBH in the multi-objective context where the stakeholder aims to optimize multiple objectives simultaneously, for example a customer-centric objective such as the total waiting times and a server-centric criterion such as the total system cost. Last but not least, the tariff definition for beehive usage is another interesting topic that is the focus of pricing problems in bi-level context. This requires the reformulation of the current problem as a bi-level model to capture the interaction between the beehive owner and the logistics manager.