The Multi-Dimensional Interaction Effect of Culture, Leadership Style, and Organizational Commitment on Employee Involvement within Engineering Enterprises: Empirical Study in Taiwan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Culture

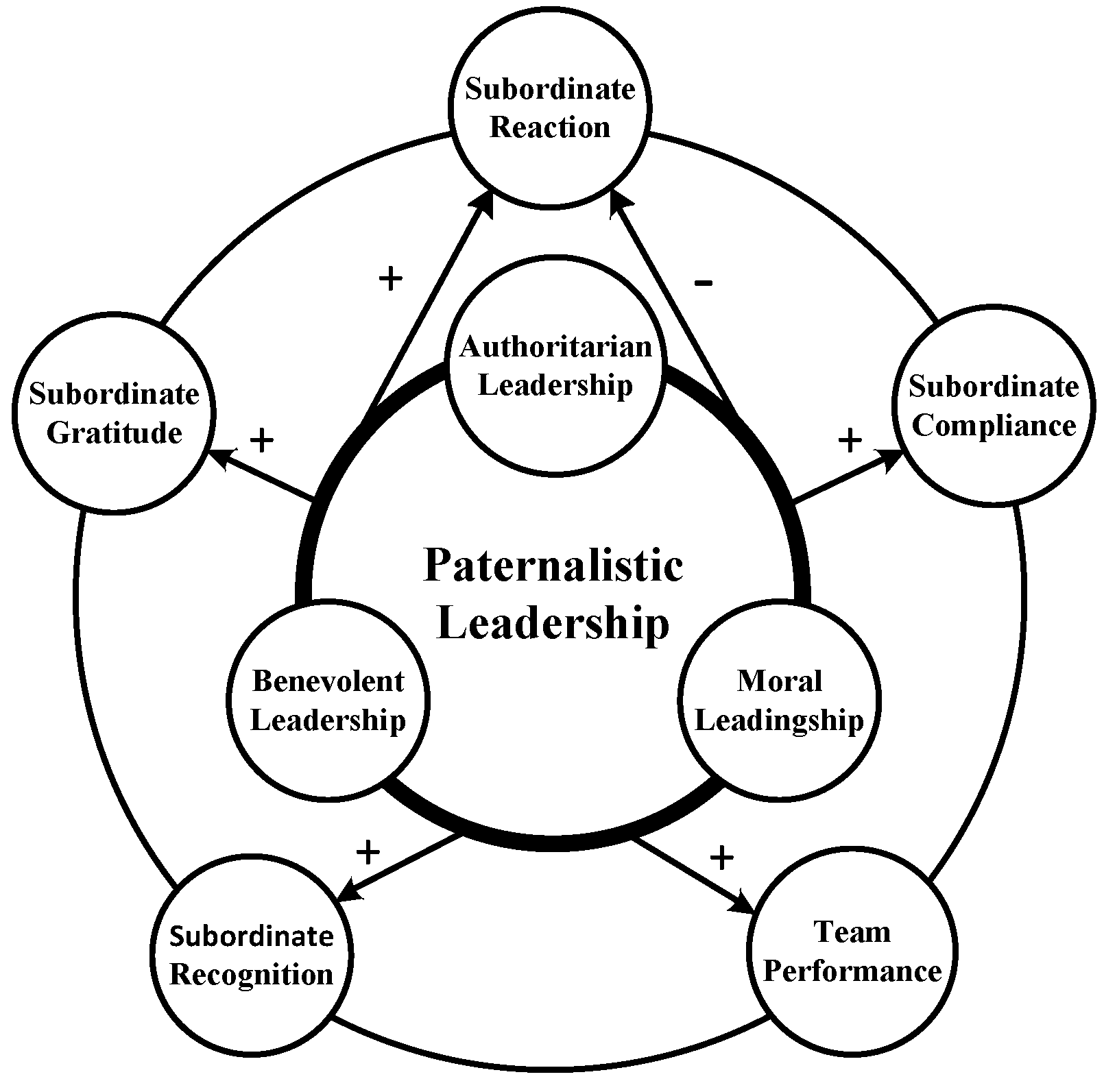

2.2. Paternalistic Leadership

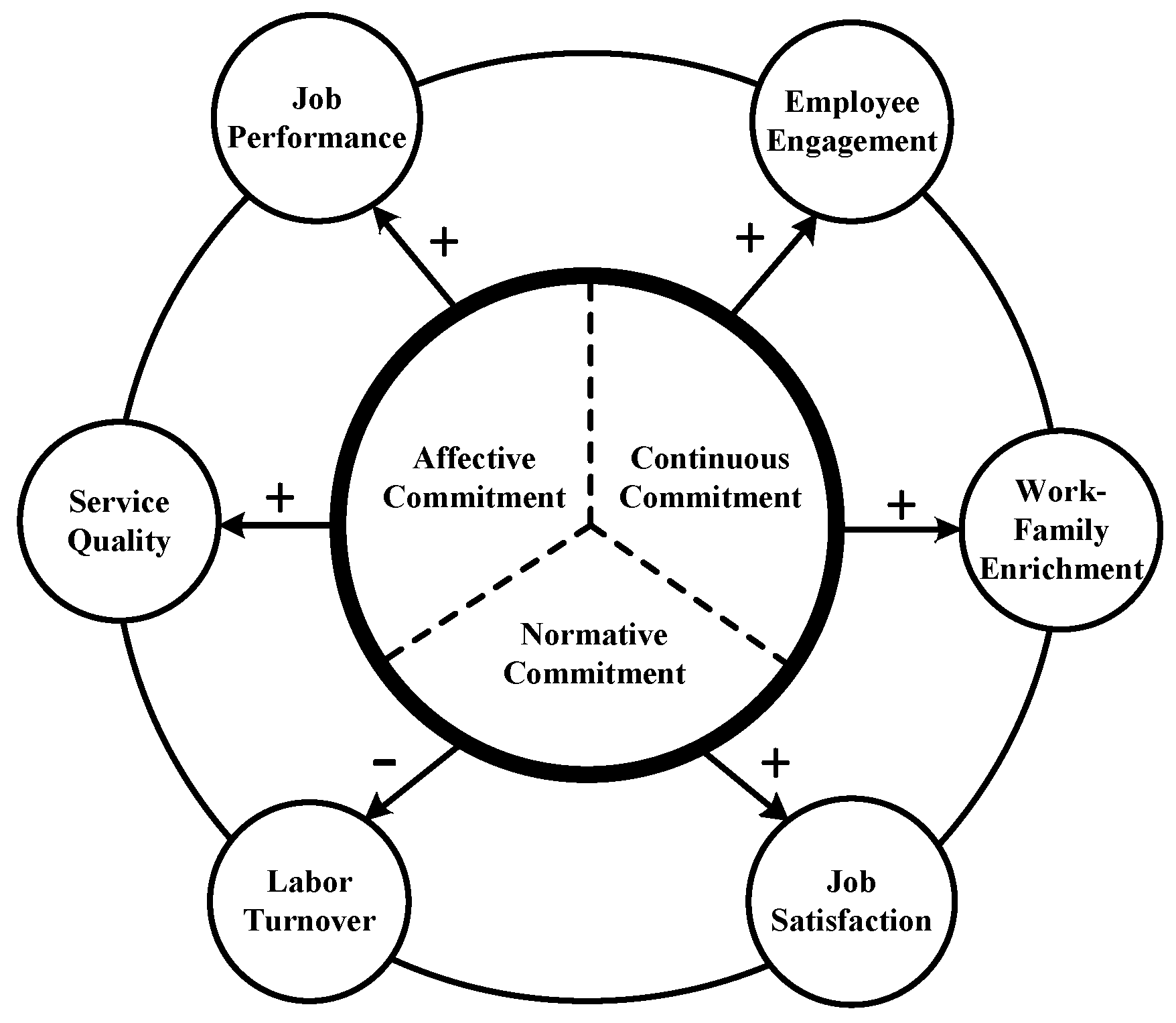

2.3. Organizational Commitment

2.4. Job Involvement

2.5. Brief Summary

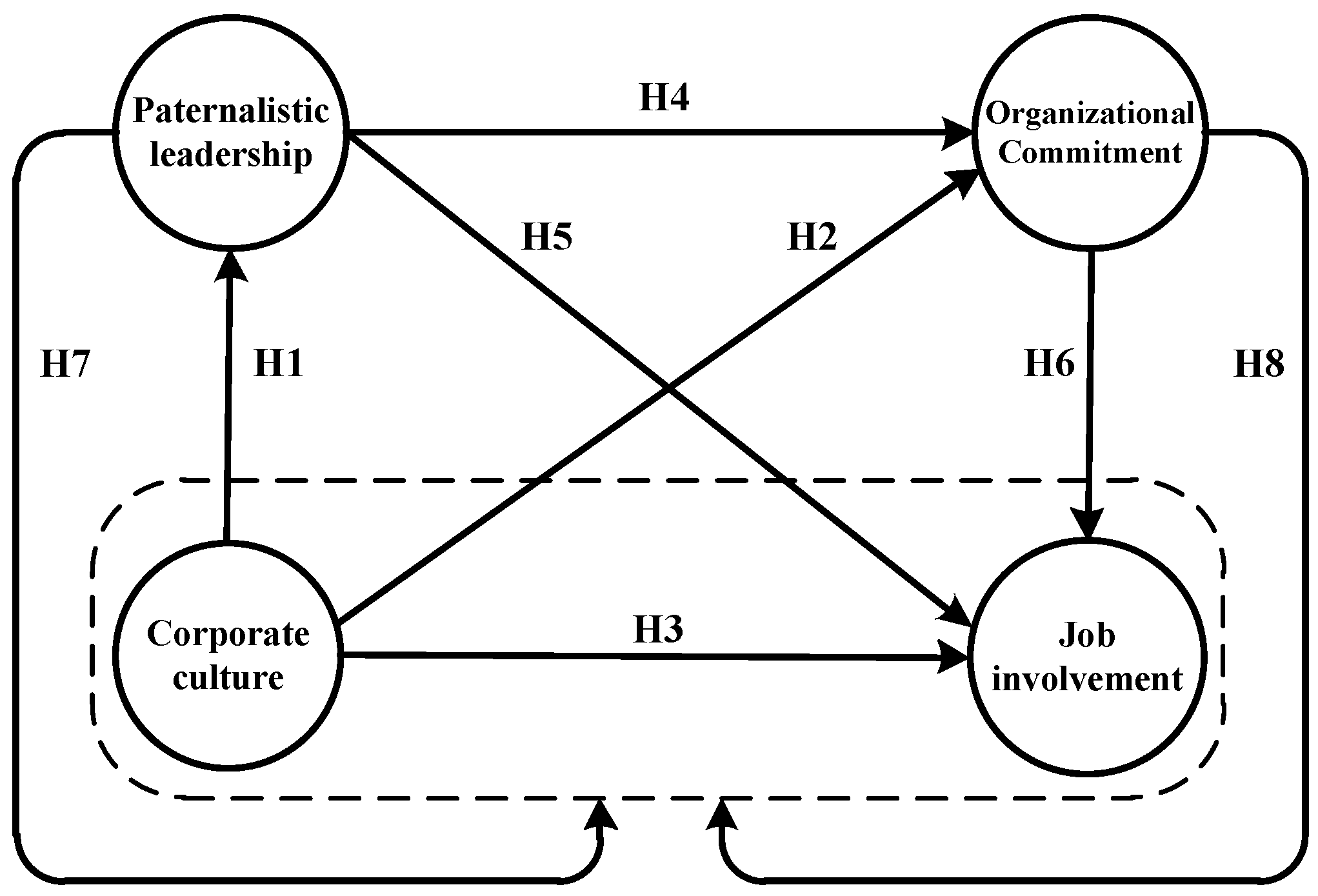

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Study Hypothesis

3.1.1. Relationship between Corporate Culture and Paternalistic Leadership Style in the Engineering Industry

3.1.2. Relationship between Corporate Culture and Organizational Commitment in the Engineering Industry

3.1.3. Relationship between Corporate Culture and Job Involvement in the Engineering Industry

3.1.4. Relationship between Paternalistic Leadership and Organizational Commitment in the Engineering Industry

3.1.5. Relationship between Paternalistic Leadership and Job Involvement in the Engineering Industry

3.1.6. Relationship between Organizational Commitment and Job Involvement in the Engineering Industry

3.1.7. Relationship between Paternalistic Leadership and Organizational Commitment in Corporate Culture and Job Involvement in the Engineering Industry

4. Personal Attributes and Variable Operational Definition

5. Results Analysis

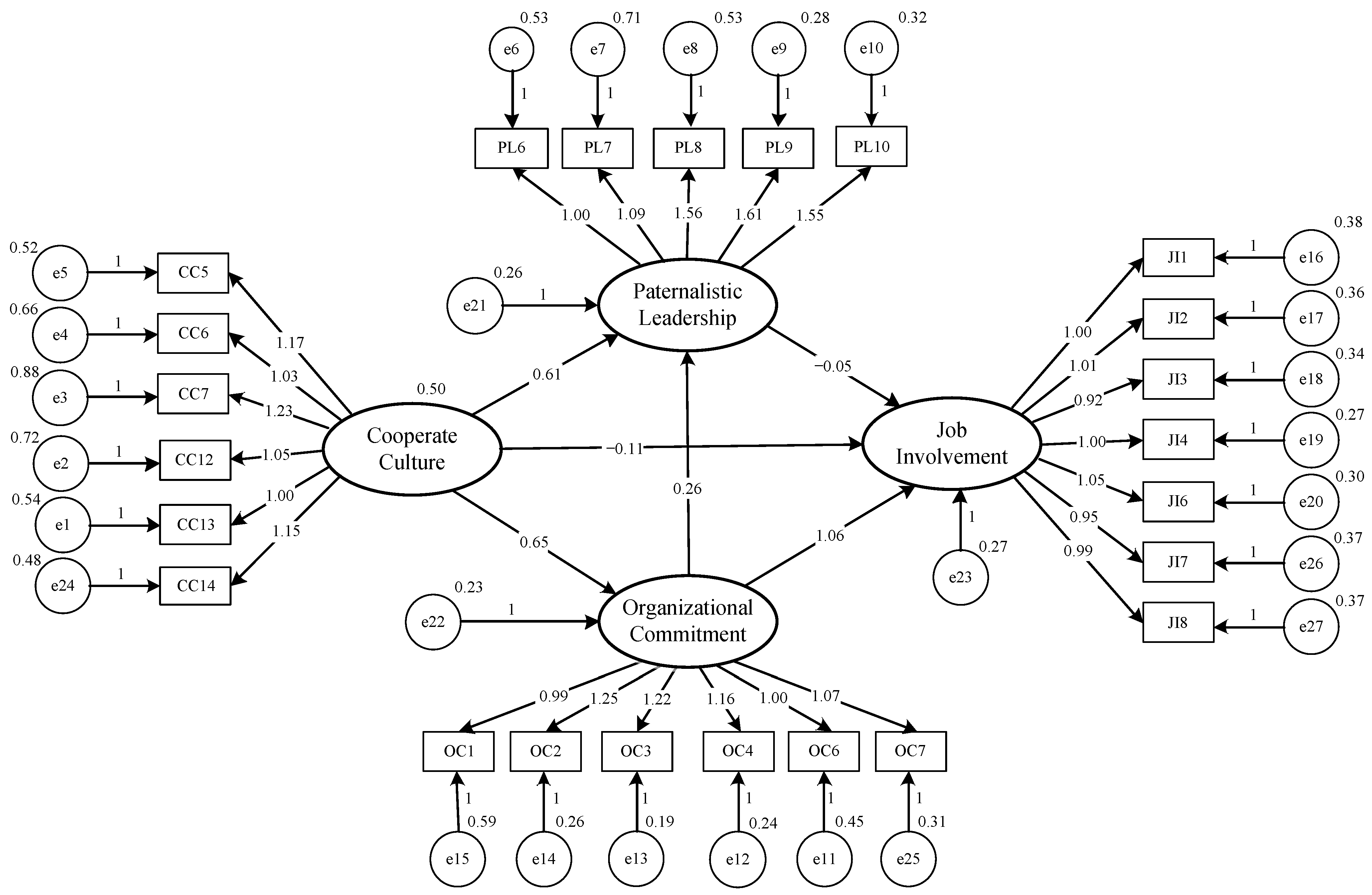

5.1. Correction of the Original Measurement Model

5.2. Result Analysis of the Correction Model

5.3. Participation in the Analysis of the Investigators’ Various Components

5.4. Reliability Analysis and Related Analysis

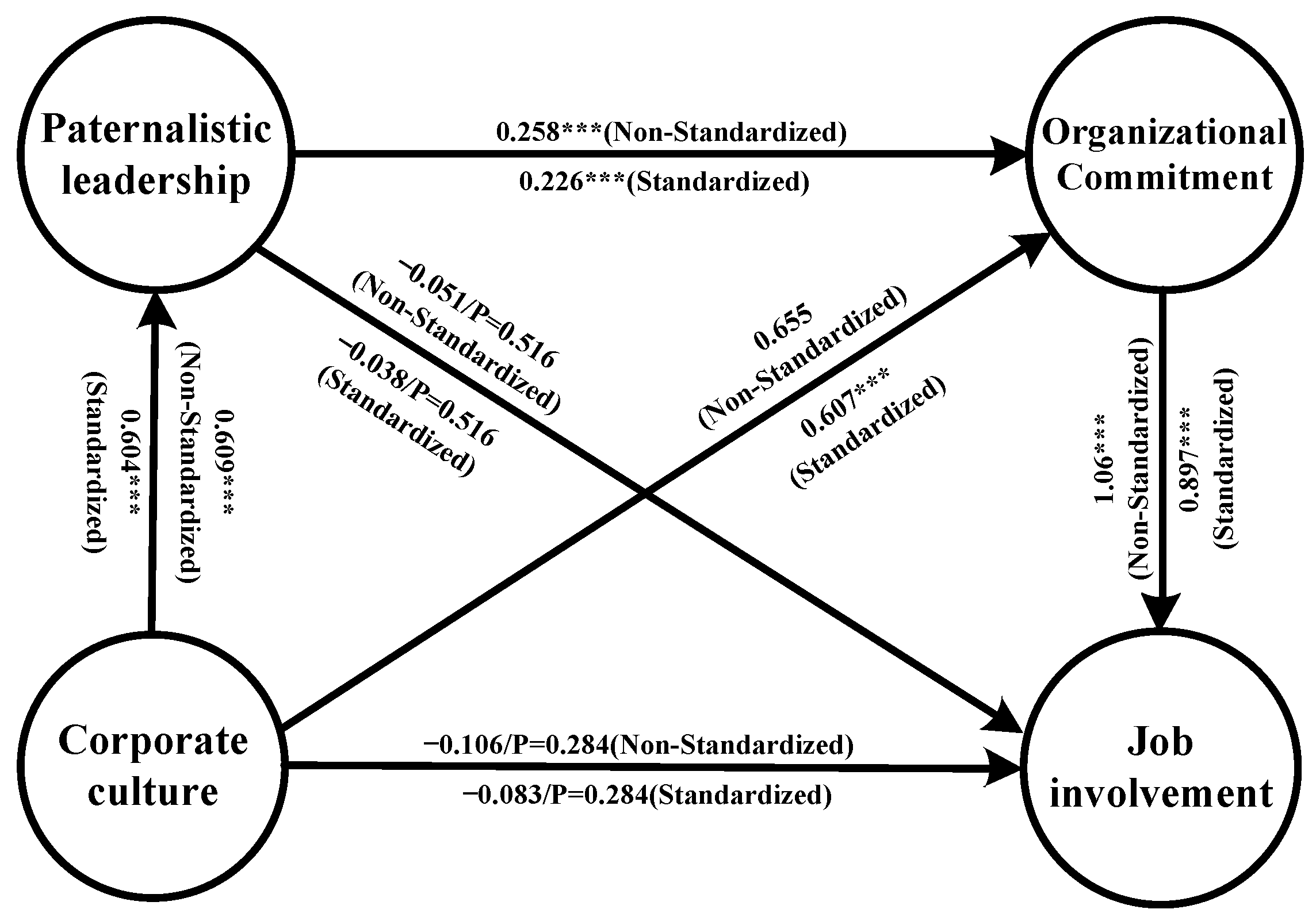

5.5. Structural Equation Analysis

6. Implications and Conclusions

6.1. Research Results

6.2. The Practical Value of the Research Results

6.3. Future Research Recommendations

- (1)

- The survey data of this study are mainly from local engineering enterprises in Taiwan. Future studies should focus on multinational engineering enterprises in Taiwan or Chinese companies overseas with engineering industry backgrounds to confirm whether there are similar conclusions.

- (2)

- This research focuses on the engineering industry, in the future, the feminine or triad leadership model will be compared to paternalistic leadership to test the similarities or differences.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cuganesan, S.; Steele, C.; Hart, A. How senior management and workplace norms influence information security attitudes and self-efficacy. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2018, 37, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, D.; Hodges, A. Corporate Social Opportunity! Seven Steps to Make Corporate Social Responsibility Work for Your Business; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Frankwick, G.L.; Nguyen, B.H. Should firms consider employee input in reward system design? The effect of participation on market orientation and new product performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2012, 29, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Chen CH, V.; Li, C.I. The influence of leader’s spiritual values of servant leadership on employee motivational autonomy and eudaemonic well-being. J. Relig. Health 2013, 52, 418–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryson, J.M.; Gibbons, M.J.; Shaye, G. Enterprise schemes for nonprofit survival, growth, and effectiveness. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2001, 11, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Leadership That Gets Results (Harvard Business Review Classics); Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kerzner, H. Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and Controlling; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbeibu, S.; Senadjki, A.; Gaskin, J. The moderating effect of benevolence on the impact of organisational culture on employee creativity. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 90, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Giuliano, P. Culture and institutions. J. Econ. Lit. 2015, 53, 898–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doise, M.L. An Integration of Corporate Culture and Strategy: The Interrelationships and Impact on Firm Performance; University of Arkansas: Fayetteville, AR, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.S.; Kilmann, R.H. The role of the reward system for a total quality management based strategy. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2001, 14, 110–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, C.; Gani, L.; Jermias, J. Performance implications of misalignment among business strategy, leadership style, organizational culture and management accounting systems. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2021. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putrawan, I. Leadership and self-efficacy: Its effect on employees motivation. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, D.R. Corporate Culture and Organizational Effectiveness; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siengthai, S.; Swierczek, F.; Bamel, U.K. The effects of organizational culture and commitment on employee innovation: Evidence from Vietnam’s IT industry. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2019, 13, 719–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifirad, M.S.; Ataei, V. Organizational culture and innovation culture: Exploring the relationships between constructs. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2012, 33, 494–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Lawrence, P.R.; Puranam, P. Adaptation in vertical relationships: Beyond incentive conflict. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 415–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawirosumarto, S.; Setyadi, A.; Khumaedi, E. The influence of organizational culture on the performance of employees at University of Mercu Buana. Int. J. Law Manag. 2017, 59, 950–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H. Mintzberg on Management: Inside Our Strange World of Organizations; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Aramali, V.; Gibson Jr, G.E.; El Asmar, M.; Cho, N. Earned Value Management System State of Practice: Identifying Critical Subprocesses, Challenges, and Environment Factors of a High-Performing EVMS. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena-Manzanares, F.; García-Segura, T.; Pellicer, E. Organizational Factors That Drive to BIM Effectiveness: Technological Learning, Collaborative Culture, and Senior Management Support. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okakpu, A.; GhaffarianHoseini, A.; Tookey, J.; Haar, J.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A. Exploring the environmental influence on BIM adoption for refurbishment project using structural equation modelling. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2020, 16, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lu, H.; Hu, W.; Gao, X.; Pishdad-Bozorgi, P. Understanding Behavioral Logic of Information and Communication Technology Adoption in Small-and Medium-Sized Construction Enterprises: Empirical Study from China. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 05020013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J.; Heine, S.J.; Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 2010, 33, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, N.J.; Sin, H.P.; Ponnapalli, A.R.; Ozgen, S. Benevolence and authority as WEIRDly unfamiliar: A multi-language meta-analysis of paternalistic leadership behaviors from 152 studies. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakitapoğlu-Aygün, Z.; Gumusluoglu, L.; Erturk, A.; Scandura, T.A. Two to Tango? A cross-cultural investigation of the leader-follower agreement on authoritarian leadership. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, S.; Shafi, A.; Asadullah, M.A.; Qun, W.; Khadim, S. Linking paternalistic leadership to follower’s innovative work behavior: The influence of leader–member exchange and employee voice. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 1354–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.C.; Cheng, B.S. When does benevolent leadership lead to creativity? The moderating role of creative role identity and job autonomy. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedahanov, A.T.; Bozorov, F.; Sung, S. Paternalistic leadership and innovative behavior: Psychological empowerment as a mediator. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.P.; Jhang, C.; Wang, Y.M. Learning value-based leadership in teams: The moderation of emotional regulation. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 16, 1387–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Hempel, P.S.; Yu, M. Tough love and creativity: How authoritarian leadership tempered by benevolence or morality influences employee creativity. Br. J. Manag. 2020, 31, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, K.; Johnson, D.E.; Wu, M. Moral leadership and psychological empowerment in China. J. Manag. Psychol. 2012, 27, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huai, M.Y.; Xie, Y.H. Paternalistic leadership and employee voice in China A dual process model. Leadersh. Q. 2015, 26, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.P.; Eberly, M.B.; Chiang, T.J.; Farh, J.L.; Cheng, B.S. Affective trust in Chinese leaders: Linking paternalistic leadership to employee performance. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 796–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.S.; Chou, L.F.; Wu, T.Y.; Huang, M.P.; Farh, J.L. Paternalistic leadership and subordinate responses: Establishing a leadership model in Chinese organizations. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 7, 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.C.; Tsai, C.Y.; Dionne, S.D.; Yammarino, F.J.; Spain, S.M.; Ling, H.C.; Cheng, B.S. Benevolence-dominant, authoritarianism-dominant, and classical paternalistic leadership: Testing their relationships with subordinate performance. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhong, Z.; Chen, C.W.; Brewster, C. Two-way in-/congruence in three components of paternalistic leadership and subordinate justice: The mediating role of perceptions of renqing. Asian Bus. Manag. 2021, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, L.J.; Cheng, B. Social orientation in Chinese societies: A comparison of employees from Taiwan and Chinese Mainland. Chin. J. Psychol. 2001, 43, 207. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1783.1/11847 (accessed on 4 January 2001).

- Zhang, N.; Liu, S.; Pan, B.; Guo, M. Paternalistic Leadership and Safety Participation of High-Speed Railway Drivers in China: The Mediating Role of Leader-Member Exchange. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 591670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, J.; Liu, X. An empirical investigation of trust in AI in a Chinese petrochemical enterprise based on institutional theory. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew YT, E.; Atay, E.; Bayraktaroglu, S. Female Engineers’ Happiness and Productivity in Organizations with Paternalistic Culture. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 05020005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Li, F.; Leung, K. Whipping into shape: Construct definition, measurement, and validation of directive-achieving leadership in Chinese culture. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2017, 34, 537–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.; Xie, Q.; Hu, X.; Wang, X.; Meng, H. A dual perspective on risk perception and its effect on safety behavior: A moderated mediation model of safety motivation, and supervisor’s and coworkers’ safety climate. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 134, 105350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M. Employee—Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Angle, H.L.; Perry, J.L. An empirical assessment of organizational commitment and organizational effectiveness. Adm. Sci. Q. 1981, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L.T.; Freeman, D.M.; Rush, M.C.; Lance, C.E. Motivational bases of affective organizational commitment: A partial test of an integrative theoretical model. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1999, 72, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.P.; Judge, T.A. Organizational Behavior; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2013; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Atmojo, M. The influence of transformational leadership on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and employee performance. Int. Res. J. Bus. Stud. 2015, 5, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Bhatnagar, J. Mediator analysis of employee engagement: Role of perceived organizational support, PO fit, organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Vikalpa 2013, 38, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.T.; Ng, Y.N.K.; Casimir, G. Confucian dynamism, affective commitment, need for achievement, and service quality: A study on property managers in Hong Kong. Serv. Mark. Q. 2011, 32, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis-Sramek, B.; Droge, C.; Mentzer, J.T.; Myers, M.B. Creating commitment and loyalty behavior among retailers: What are the roles of service quality and satisfaction? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2009, 37, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.L. Service quality and the training of employees: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zopiatis, A.; Constanti, P.; Theocharous, A.L. Job involvement, commitment, satisfaction and turnover: Evidence from hotel employees in Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo BK, B.; Park, S. Career satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention: The effects of goal orientation, organizational learning culture and developmental feedback. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2010, 31, 482–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin-Fah, B.C.; Foon, Y.S.; Chee-Leong, L.; Osman, S. An exploratory study on turnover intention among private sector employees. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manata, B.; Garcia, A.J.; Mollaoglu, S.; Miller, V.D. The effect of commitment differentiation on integrated project delivery team dynamics: The critical roles of goal alignment, communication behaviors, and decision quality. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwela, S.; van der Bank, F. Understanding intention to quit amongst artisans and engineers: The facilitating role of commitment. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 19, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Duan, K. Work-to-family conflict, job burnout, and project success among construction professionals: The moderating role of affective commitment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montalbán-Domingo, L.; Pellicer, E.; García-Segura, T.; Sanz-Benlloch, A. An integrated method for the assessment of social sustainability in public-works procurement. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 89, 106581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, L.; Xia, D.; Ni, G.; Cui, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, W. Influence mechanism of job satisfaction and positive affect on knowledge sharing among project members: Moderator role of organizational commitment. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2019, 27, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewobi, L.O.; Oke, A.E.; Adeneye, T.D.; Jimoh, R.A. Influence of organizational commitment on work–life balance and organizational performance of female construction professionals. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2019, 26, 2243–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-León, I.M.; Olmedo-Cifuentes, I.; Ramón-Llorens, M.C. Work, personal and cultural factors in engineers’ management of their career satisfaction. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2018, 47, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.L.; Steiner, J.F. Organizational Behavior: Human Behavior at Work; McGraw-Hill College: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shantz, A.; Arevshatian, L.; Alfes, K.; Bailey, C. The effect of HRM attributions on emotional exhaustion and the mediating roles of job involvement and work overload. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2016, 26, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreitner, R.; Kinicki, A. Organizational Behavior; Mc Graw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.P. A meta-analysis and review of organizational research on job involvement. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 120, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Chiu, S.F. The mediating role of job involvement in the relationship between job characteristics and organizational citizenship behaviour. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 474–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamri, M.S.; Al-Duhaim, T.I. Employees perception of training and its relationship with organizational commitment among the employees working at Saudi industrial development fund. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2017, 8, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rujipak, V.; Limprasert, S. International students’ adjustment in Thailand. ABAC J. 2016, 36, 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Effects of the application of mobile learning to criminal law education on learning attitude and learning satisfaction. EURASIA J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2018, 14, 3355–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Farr, D.; Walsh, B.M.; McGonagle, A.K. Uncivil supervisors and perceived work ability: The joint moderating roles of job involvement and grit. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M.R.; Russell, M.; Cooper, M.L. Job stressors, job involvement and employee health: A test of identity theory. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1995, 68, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1974, 13, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Sleebos, E. Organizational identification versus organizational commitment: Self-definition, social exchange, and job attitudes. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2006, 27, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pheng, L.S.; Teo, J.A. Implementing total quality management in construction firms. J. Manag. Eng. 2004, 20, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Song, S.; Lee, D.; Kim, D.; Lee, S.; Irizarry, J. A Conceptual Model of Multi-Spectra Perceptions for Enhancing the Safety Climate in Construction Workplaces. Buildings 2021, 11, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, N.; Jiang, Z.; Fang, D.; Anumba, C.J. An agent-based modeling approach for understanding the effect of worker-management interactions on construction workers’ safety-related behaviors. Autom. Constr. 2019, 97, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Chan, A.P. Evaluation of multi-level intervention strategies for a psychologically healthy construction workplace in Nigeria. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2020, 19, 509–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.C.; Thomas, K.G.; Du Plessis, M. An evaluation of job crafting as an intervention aimed at improving work engagement. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2020, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, K.; Gedik, N.K.; Okun, O.; Sen, C. Impact of cultural values on leadership roles and paternalistic style from the role theory perspective. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 17, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, I.N.; Supriyanto, A.S.; Ekowati, V.M.; Ertanto, A.H. Factor Influencing Employee Performance: The Role of Organizational Culture. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okun, O.; Şen, C.; Arun, K. How do paternalistic leader behaviors shape xenophobia in business life? Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2020, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.P.; Timothy, A.J. Organizational Behavior; Salemba Empat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Bhutto, T.A.; Nasiri, A.R.; Shaikh, H.A.; Samo, F.A. Organizational innovation: The role of leadership and organizational culture. Int. J. Public Leadersh. 2018, 14, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, K.; Şen, C.; Okun, O. How does leadership effectiveness related to the context? Paternalistic leadership on non-financial performance within a cultural tightness-looseness model? JEEMS J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 2020, 25, 503–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, R.; Wang, A.C.; Farh, J.L. Asian conceptualizations of leadership: Progresses and challenges. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2020, 7, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajan, T.T.; Singh, B.; Solansky, S. Performance appraisal fairness, leader member exchange and motivation to improve performance: A study of US and Mexican employees. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 85, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham Thi, T.D.; Ngo, A.T.; Duong, N.T.; Pham, V.K. The Influence of Organizational Culture on Employees’ Satisfaction and Commitment in SMEs: A Case Study in Vietnam. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchalina, L.; Ahmad, H.; Gelaidan, H.M. Employees’ commitment to change: Personality traits and organizational culture. J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2020, 37, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, E.J. Organizational culture, leaders’ vision of talent, and HR functions on career changers’ commitment: The moderating effect of training in South Korea. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2019, 57, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.S.; Reeves, P.; Chapin, M. A lexical approach to identifying dimensions of organizational culture. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do Huu Hai, N.M.H.; Van Tien, N. The Influence of Corporate Culture on Employee Commitment. In Econometrics for Financial Applications Studies in Computational Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, O.O.; Kibera, F. Organizational Culture and Performance: Evidence from Microfinance Institutions in Kenya. SAGE Open 2019, 9, 2158244019835934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulugeta, A. The Effect of Organizational Culture on Employees Performance in Public Service Organization of Dire Dawa Administration. Dev. Ctry. Stud. 2020, 10, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Martínez, I.; Duhamel, F. Translating sustainability into competitive advantage: The case of Mexico’s hospitality industry. Corp. Governance Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2019, 19, 1324–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, G.; Liu, W. Impact of perceived organizational culture on job involvement and subjective well-being: A moderated mediation model. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2019, 47, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünler, E.; Kılıç, B. Paternalistic Leadership and Employee Organizational Attitudes: The Role of Positive/Negative Affectivity. SAGE Open 2019, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.-Y.; Wang, L. The Mediating Effect of Ethical Climate on the Relationship Between Paternalistic Leadership and Team Identification: A Team-Level Analysis in the Chinese Context. J. Bus. Ethic 2015, 129, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C. How Does Paternalistic Style Leadership Relate to Team Cohesiveness in Soccer Coaching? Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2013, 41, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Milliman, J.; Lucas, A. Effects of CSR on employee retention via identification and quality-of-work-life. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 1163–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Hahn, J. Improving Millennial Employees’ OCB: A Multilevel Mediated and Moderated Model of Ethical Leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ur Rehman, S.; Bhatti, A.; Chaudhry, N.I. Mediating effect of innovative culture and organizational learning be-tween leadership styles at third-order and organizational performance in Malaysian SMEs. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Ye, J.; Li, Y. Combined influence of exchange quality and organizational identity on the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee innovation: Evidence from China. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 6, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.Y.; Lin, C.-P. Is Paternalistic Leadership a Double-Edged Sword for Team Performance? The Mediation of Team Identification and Emotional Exhaustion. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2021, 28, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, A. A Meta-Analytic Review of Paternalistic Leadership. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 69, 960–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakitapoğlu-Aygün, Z.; Gumusluoglu, L.; Scandura, T.A. How Do Different Faces of Paternalistic Leaders Facilitate or Impair Task and Innovative Performance? Opening the Black Box. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2020, 27, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koveshnikov, A.; Ehrnrooth, M.; Wechtler, H. The Three Graces of Leadership: Untangling the Relative Importance and the Mediating Mechanisms of Three Leadership Styles in Russia. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2020, 16, 791–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.A.; Mahmood, M.; Fan, L. Why individual employee engagement matters for team performance? Medi-ating effects of employee commitment and organizational citizenship behaviour. Team Perform. Manag. Int. Natl. J. 2019, 25, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yook, E. Effects of Service Learning on Concept Learning about Small Group Communication. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 2018, 30, 361–369. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.H.; Tran, T.B.H. Internal marketing, employee customer-oriented behaviors, and customer behavioral responses. Psychol. Mark. 2018, 35, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H.; Bravo, G.A.; Mello Figuerôa, K.; Mezzadri, F.M. The impact of volunteer experience at sport mega-events on intention to continue volunteering: Multigroup path analysis. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 47, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maamari, B.E.; Saheb, A. How organizational culture and leadership style affect employees’ performance of genders. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2018, 26, 630–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Rubenstein, A.L.; Lin, W.; Wang, M.; Chen, X. The curvilinear effect of benevolent leadership on team performance: The mediating role of team action processes and the moderating role of team commitment. Pers. Psychol. 2018, 71, 369–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Helo, P.; Papadopoulos, T.; Childe, S.J.; Sahay, B.S. Explaining the impact of reconfigurable manufacturing systems on environmental performance: The role of top management and organizational culture. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopiah, S.; Kamaludin, M.; Sangadji, E.M.; Narmaditya, B.S. Organizational Culture and Employee Performance: An Empirical Study of Islamic Banks in Indonesia. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.E.; McGrath, M.R. The transformation of organizational cultures: A competing values perspective. In Organizational Culture; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 315–334. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B.S.; Boer, D.; Chou, L.F.; Huang, M.P.; Yoneyama, S.; Shim, D.; Sun, J.-M.; Lin, T.-T.; Chou, W.-J.; Tsai, C.-Y. Paternalistic leadership in four east asian societies: Generalizability and cultural differences of the triad model. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanungo, R.N. Measurement of job and work involvement. J. Appl. Psychol. 1982, 67, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Rehman, S.U.; García, F.J.S. Corporate social responsibility and environmental performance: The mediating role of environmental strategy and green innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 160, 120262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.U.; Bhatti, A.; Kraus, S.; Ferreira, J.J. The role of environmental management control systems for eco-logical sustainability and sustainable performance. Manag. Decis. 2020, 59, 2217–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Order | Department | Position | Specialization | Years of Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | President’s Office | Senior President | Management of planning, manufacturing, and construction | 33 |

| 2 | Production Department | Senior Vice President | Management planning and manufacturing | 30 |

| 3 | Production Department | Senior Project Manager | Planning and manufacturing management | 29 |

| 4 | Production Department | Senior Associate | Planning, manufacturing, and management | 28 |

| 5 | Production Department | Senior Associate | Planning and manufacturing management | 24 |

| 6 | Research Department | Vice President | Design and planning, technical innovation, research, and improvement | 20 |

| 7 | Research Department | Associate | Technical innovation, research, and improvement | 14 |

| 8 | Engineering Department | Senior Vice President | Management of planning, manufacturing, and construction | 31 |

| 9 | Design Department | Senior Associate | Design and planning | 30 |

| 10 | Design Department | Senior Associate | Design and planning | 24 |

| 11 | Design Department | Senior Manager | Design and planning | 27 |

| 12 | Design Department | Vice President | Management of design and planning, manufacturing, and construction | 21 |

| 13 | Design Department | Vice President | Management of design and planning, and manufacturing | 20 |

| 14 | Design Department | Manager | Design and planning | 19 |

| Facet | Title | Average | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate culture | CC5 | 4.86 | 1.097 |

| CC6 | 4.58 | 1.090 | |

| CC7 | 4.07 | 1.282 | |

| CC12 | 4.50 | 1.124 | |

| CC13 | 4.23 | 1.017 | |

| CC14 | 4.67 | 1.064 | |

| Paternalistic Leadership | PL6 | 4.50 | 0.987 |

| PL7 | 3.85 | 1.116 | |

| PL8 | 4.50 | 1.267 | |

| PL9 | 4.59 | 1.193 | |

| PL10 | 4.30 | 1.180 | |

| Job Involvement | JI1 | 4.41 | 1.089 |

| JI2 | 4.30 | 1.085 | |

| JI3 | 4.59 | 1.009 | |

| JI4 | 4.51 | 1.044 | |

| JI6 | 4.63 | 1.091 | |

| JI7 | 4.40 | 1.048 | |

| JI8 | 4.74 | 1.015 | |

| Organizational Commitment | OC1 | 4.35 | 1.078 |

| OC2 | 4.49 | 1.083 | |

| OC3 | 4.72 | 1.029 | |

| OC4 | 4.82 | 1.009 | |

| OC6 | 4.90 | 1.014 | |

| OC7 | 4.79 | 0.983 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Tai, H.-W.; Cheng, K.-T.; Wei, C.-C.; Lee, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-H. The Multi-Dimensional Interaction Effect of Culture, Leadership Style, and Organizational Commitment on Employee Involvement within Engineering Enterprises: Empirical Study in Taiwan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169963

Liu L, Tai H-W, Cheng K-T, Wei C-C, Lee C-Y, Chen Y-H. The Multi-Dimensional Interaction Effect of Culture, Leadership Style, and Organizational Commitment on Employee Involvement within Engineering Enterprises: Empirical Study in Taiwan. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):9963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169963

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Lin, Hsing-Wei Tai, Kuo-Tai Cheng, Chia-Chen Wei, Chang-Yen Lee, and Yen-Hung Chen. 2022. "The Multi-Dimensional Interaction Effect of Culture, Leadership Style, and Organizational Commitment on Employee Involvement within Engineering Enterprises: Empirical Study in Taiwan" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 9963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169963

APA StyleLiu, L., Tai, H.-W., Cheng, K.-T., Wei, C.-C., Lee, C.-Y., & Chen, Y.-H. (2022). The Multi-Dimensional Interaction Effect of Culture, Leadership Style, and Organizational Commitment on Employee Involvement within Engineering Enterprises: Empirical Study in Taiwan. Sustainability, 14(16), 9963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169963