Examining the Provincial-Level Difference and Impact Factors of Urban Household Electricity Consumption in China—Based on the Extended STIRPAT Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

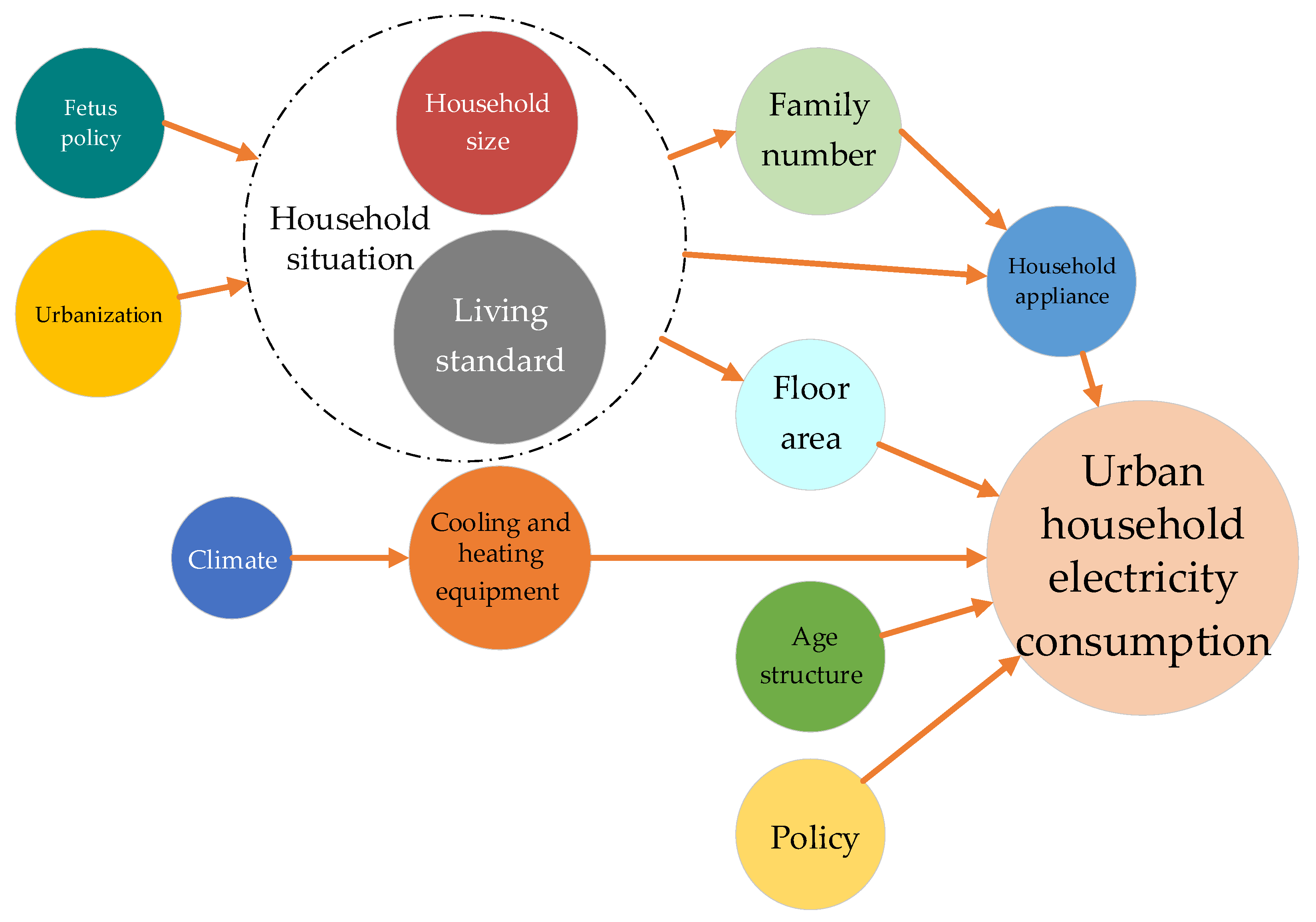

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Hypothesis Framework

3. Research Methodology

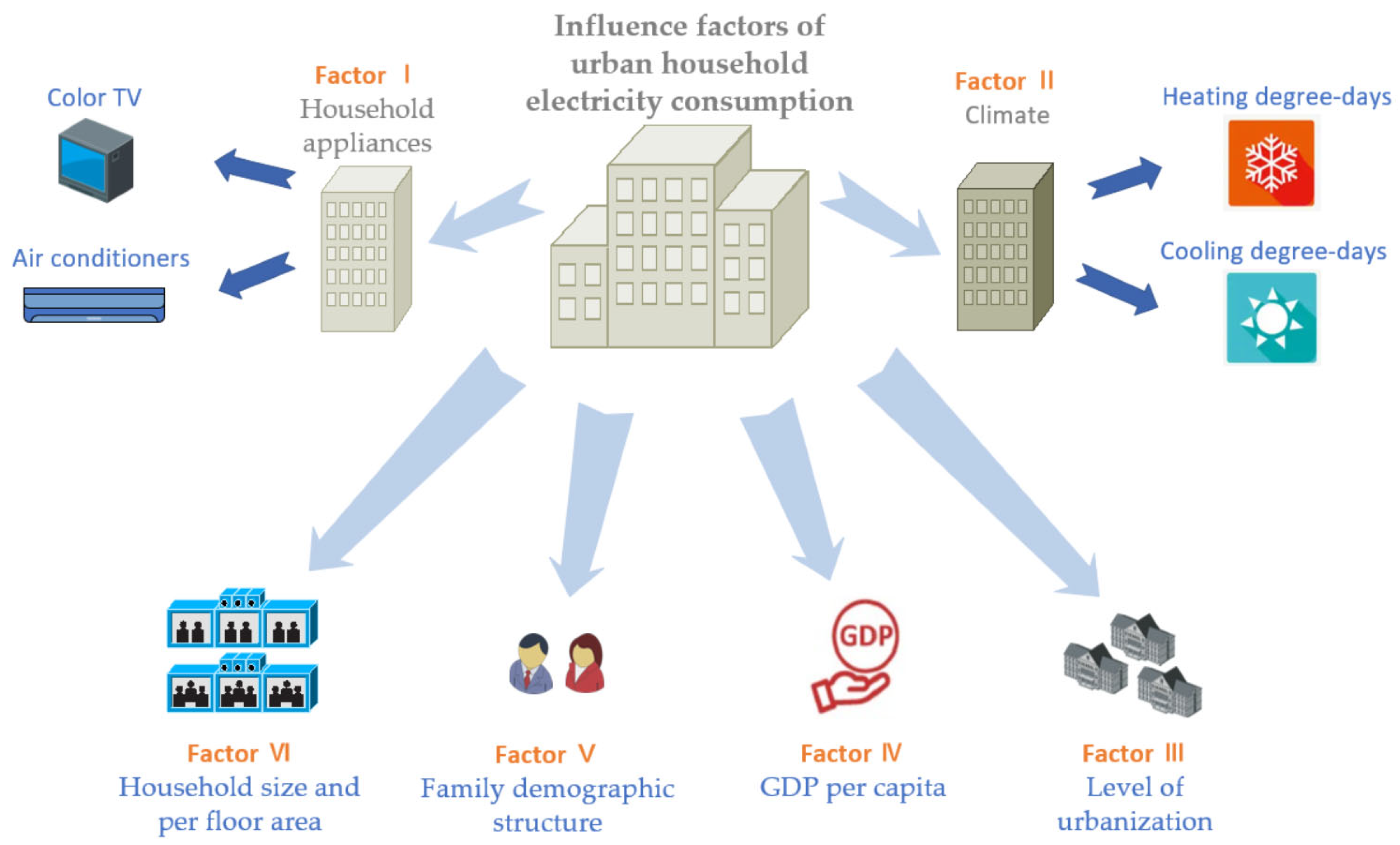

3.1. Factors Influencing UHEC

3.2. STIRPAT Model

4. Results

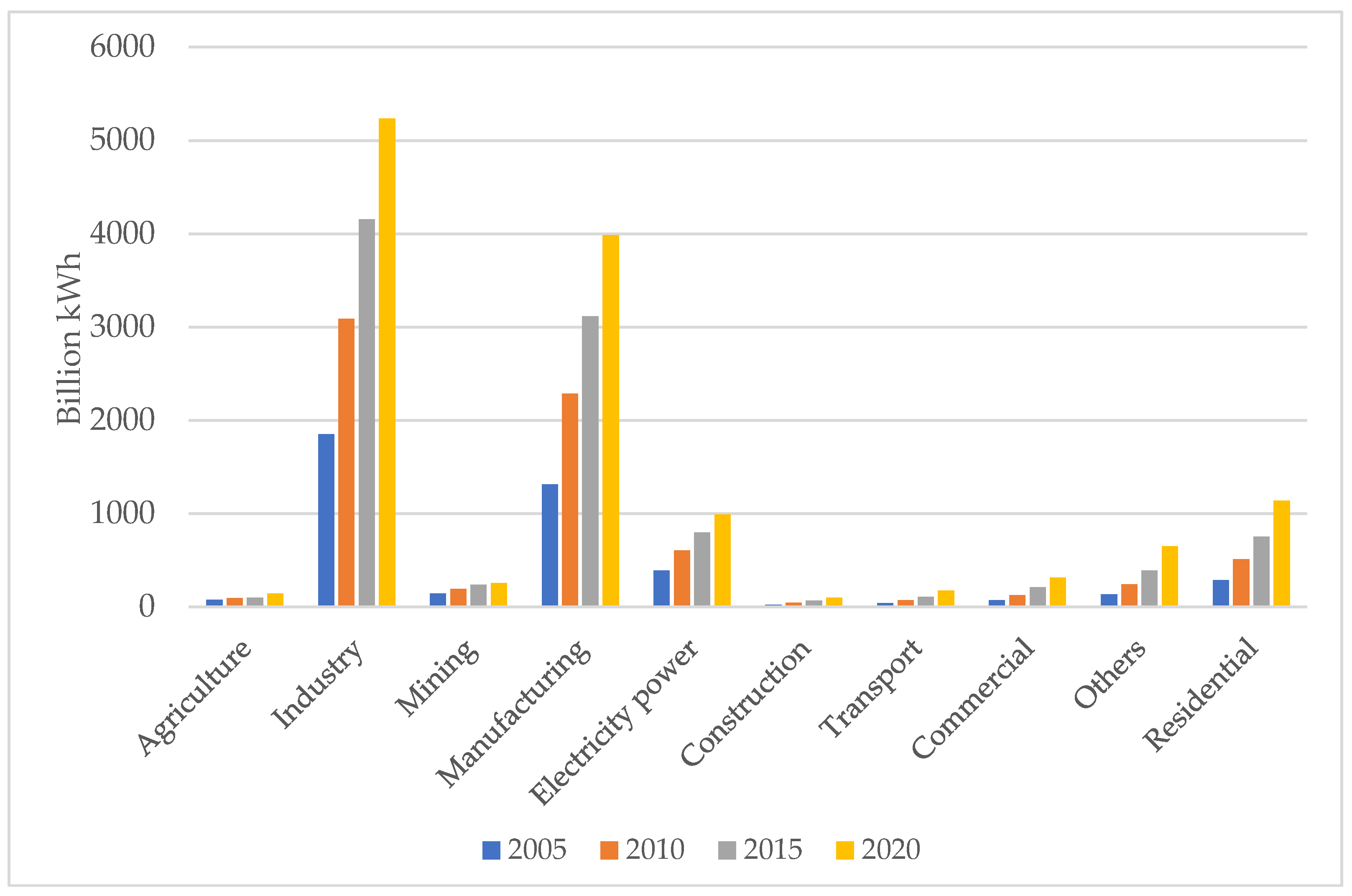

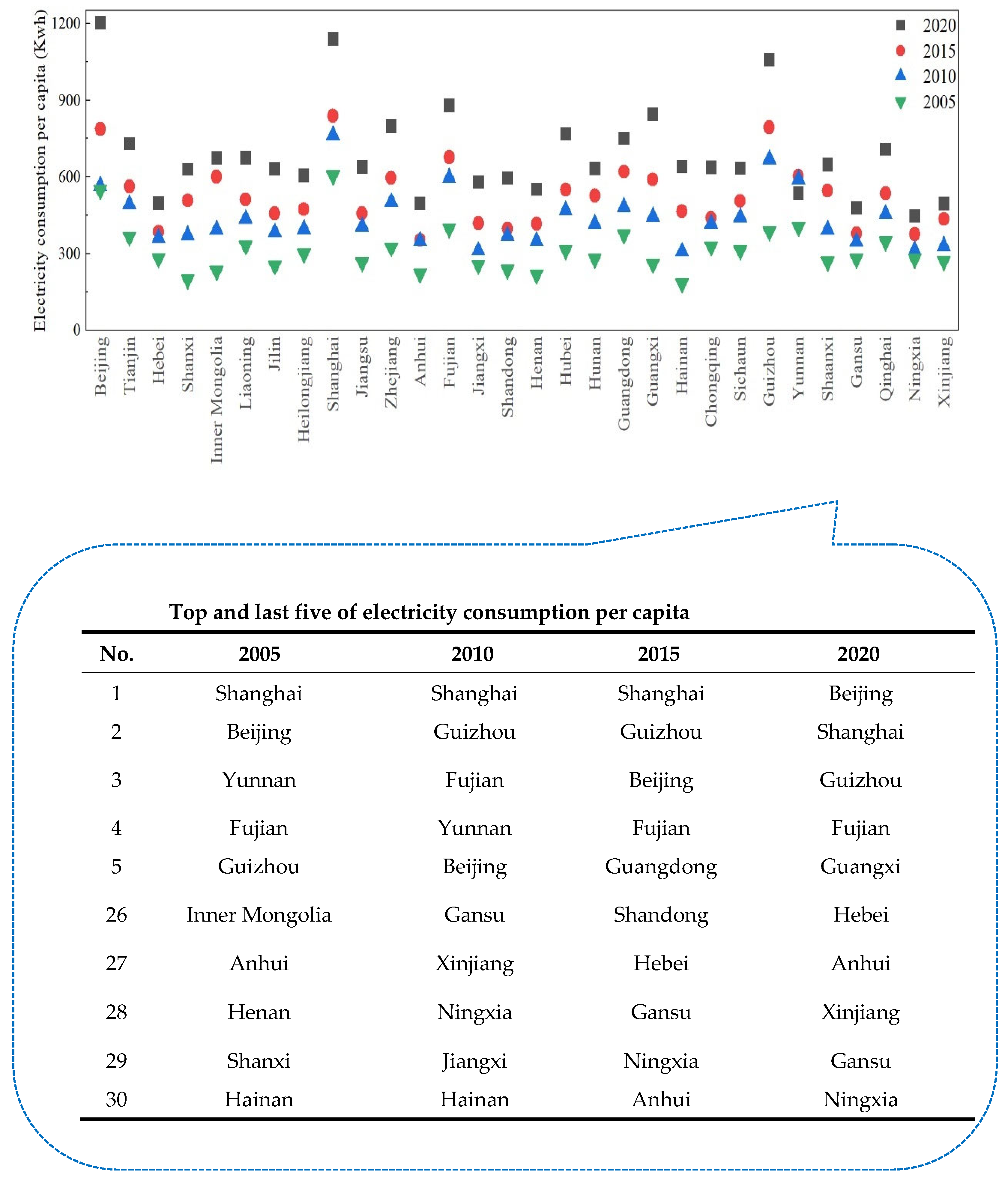

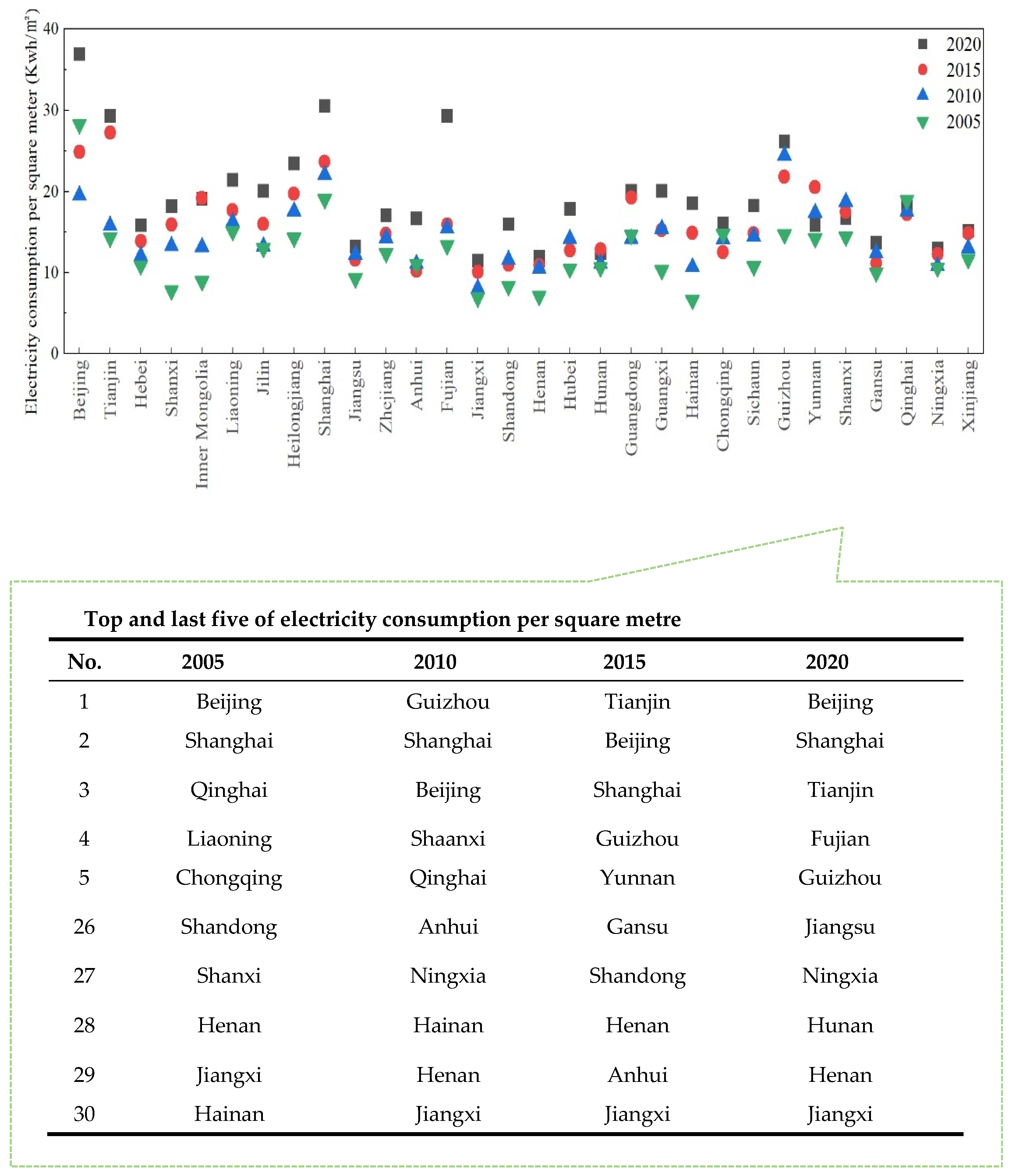

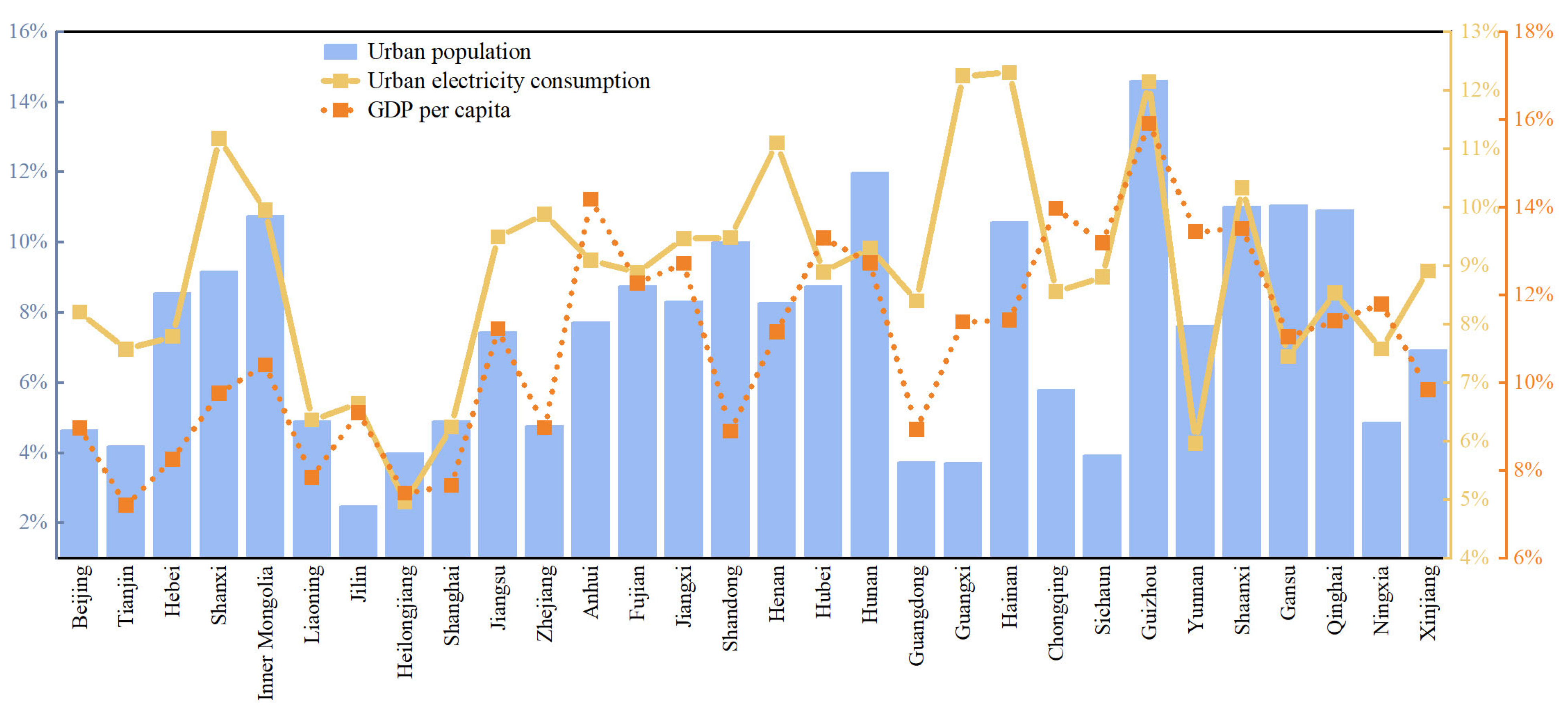

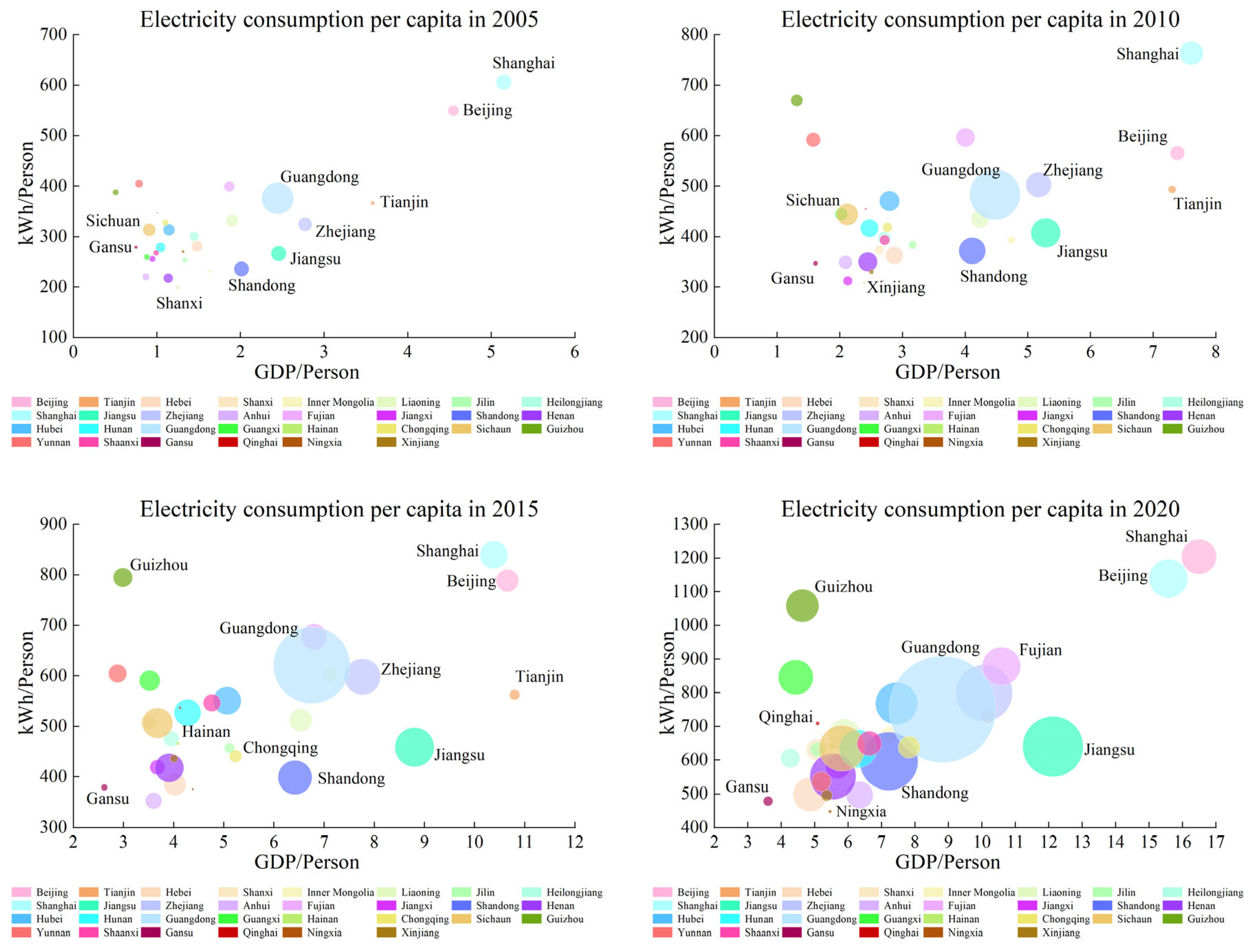

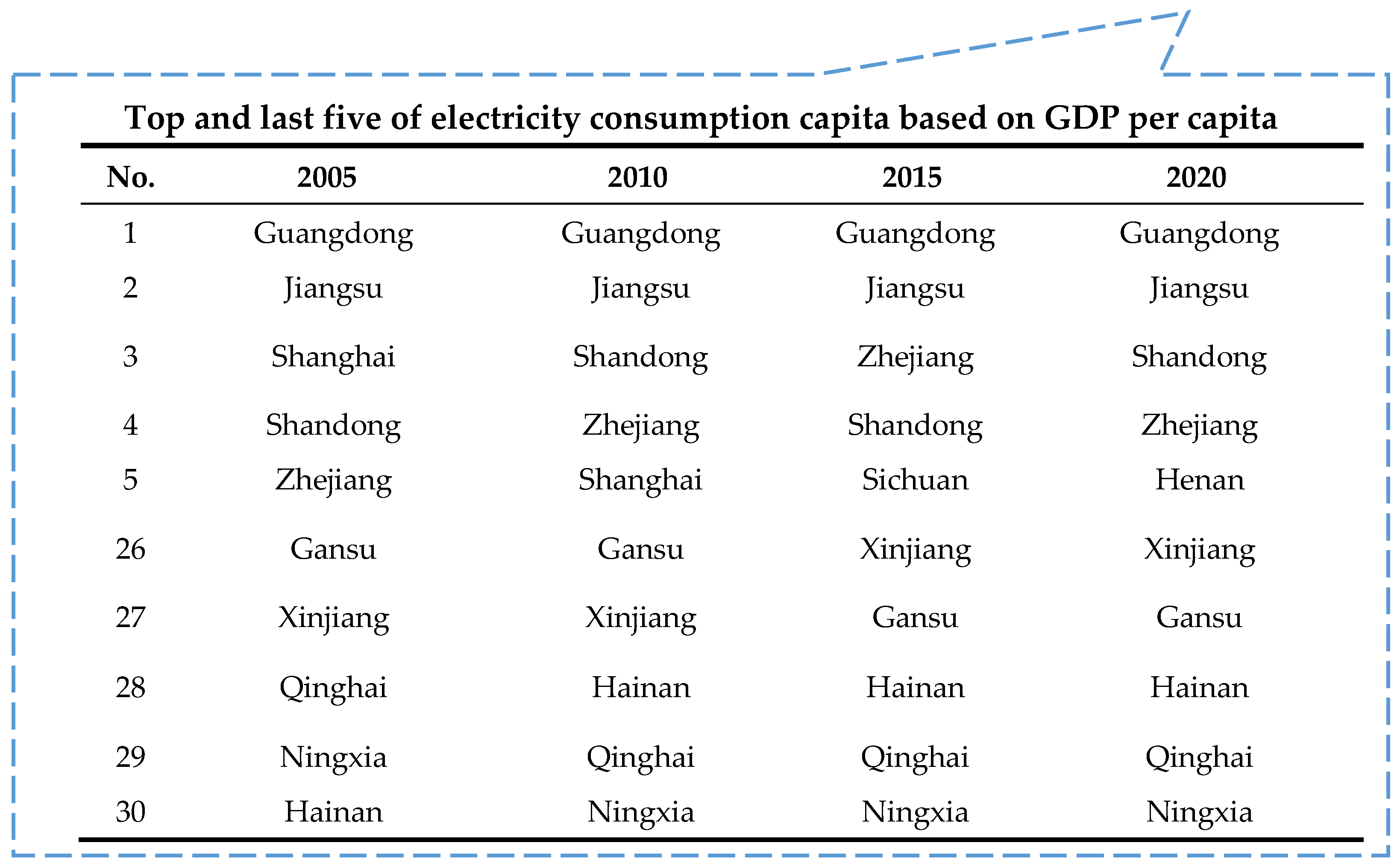

4.1. Analysis of the Results of UHEC in China

4.2. Analyses of the Impact Factors of UHEC

Parameter Estimation Results of Panel Data Model

5. Discussion

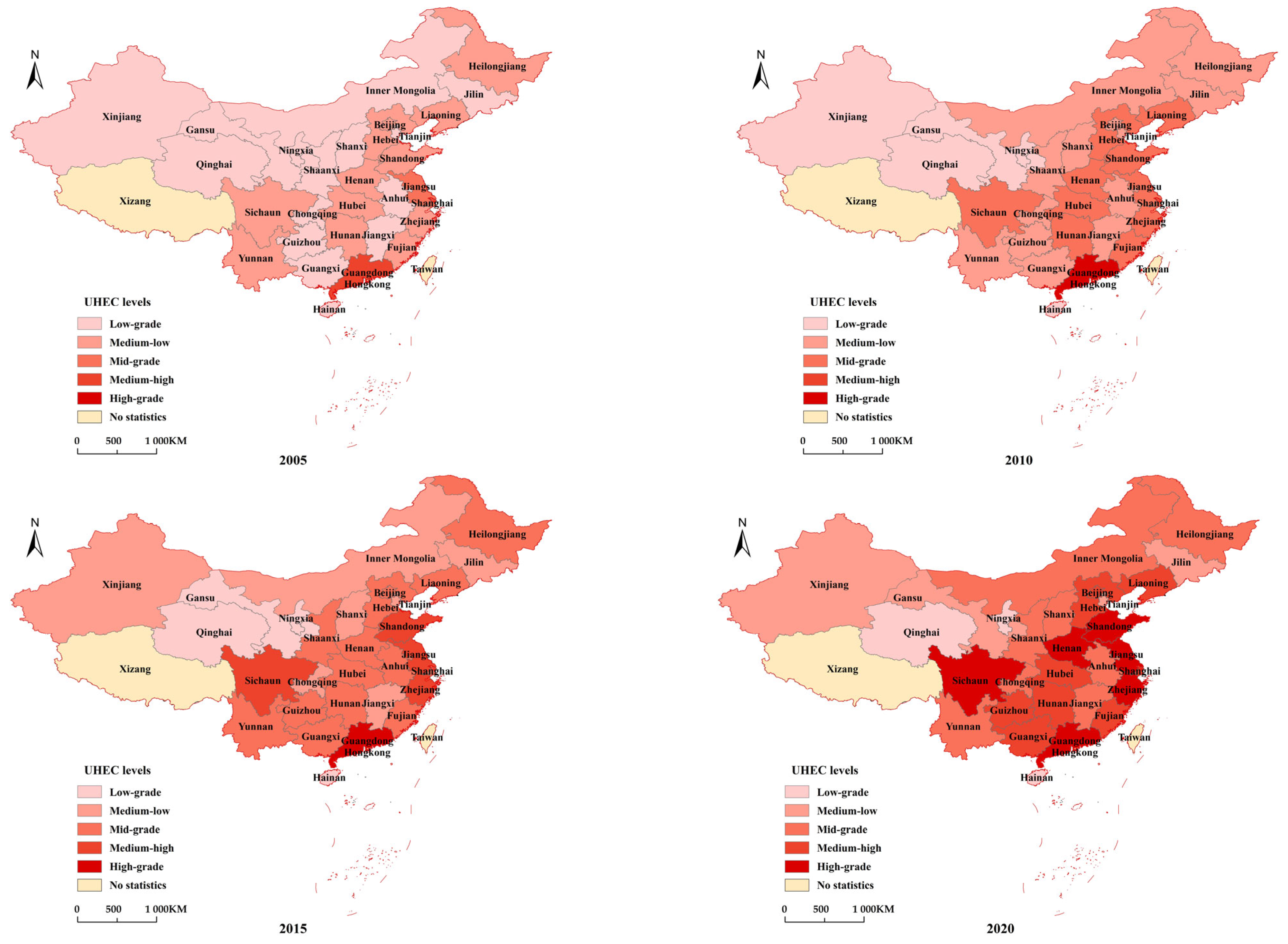

5.1. Analysis of the Difference in UHEC in China

5.2. Different Contributions of Impact Factors Affecting UHEC

- Population factors can be classified as (i) average family size and (ii) age structure, including the presence of elderly people (65 years and above). The increasing average family size in China (FSIZE) negatively contributes to UHEC, with an effect coefficient of −0.383, as supported by Brantley [40], who found that larger households were associated with lower levels of electricity in both developed and developing countries. The coefficient of influence for the presence of older people was 0.315, which suggests that an increase in the number of older individuals will lead to an increase in UHEC. This conclusion is supported by Liu [41], whose study of 150 countries showed that younger age groups consume less than older age groups, and that population aging will, to some extent, lead to an increase in heat and electricity consumption. Fintan [22] found that households with young people (18–35 years) tended to have lower electricity consumption than households in other age groups (36–55 years or 56+). Elderly people are a group of people who do not have full-time jobs and whose physical functions are declining, have an increased need for air conditioning, and are at home for extended periods of the day [32,41].

- Economic factors can be categorised as: (i) GDP per capita and (ii) factors such as electricity prices that were not included in this study. Of these, GDP per capita ranks high in terms of the impact coefficient and significantly impacts UHEC. This result is supported by Wang [42], who found that higher GDP per capita tends to be accompanied by a higher quality of life and electricity consumption. However, Yalcintas [27] demonstrated that the price of electricity has no significant impact on household electricity consumption and is not a good indicator to study; thus, it was not included in this study.

- Table 5 shows that increasing levels of urbanisation (U) had the most significant positive contribution to UHEC, with an impact coefficient of 0.657. This result is supported by Bilgili [43], who investigated ten Asian countries and found that the impact of urbanisation on energy intensity can be long or short. An analysis of Tahsin’s research shows a panel Granger causality between energy consumption [44], urbanisation, and economic growth, and that they all influence each other. Thus, it can be seen that China’s rapid urbanisation and economic development have directly led to an increase in household electricity consumption.

- Per capita housing size is also a significant factor affecting household electricity consumption. Huang [45] identified the characteristics of high-electricity-consuming households through his study, in which he found that the larger the dwelling size (larger housing area per capita), the higher the household electricity consumption for same-same populations.

- A negative correlation between HDD and UHEC was observed under the influence of temperature. Berkouwer’s [46] study of nearly 6000 households showed that an increase in temperature and a decrease in the number of HDD days results in a 6.2% reduction in annual electricity consumption per household, which supports our conclusion. However, the impact of CDD on UHEC was not as pronounced.

- Factors such as the number of household appliances owned (AC and TV) may have different effects on household electricity consumption. For example, AC may reduce household electricity consumption to some extent, possibly because households choose to purchase and use expensive but more energy-efficient AC equipment to reduce the expenditures associated with electricity consumption [47]. However, this finding is valid only for AC, and the effect for other household appliances, such as TVs, is not significant [48].

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Lin, M.; Gao, J.; Zhou, Z. Fading Attraction of the Shrinking City: An Empirical Study from an Urban Resource Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadoorian, M.O.; Eckaus, R.S.; Schlosser, C.A. Modeling climate feedbacks to electricity demand: The case of China. Energy Econ. 2008, 30, 1577–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Ma, X.; Cai, W.; Cai, W. Low carbon roadmap of residential building sector in China: Historical mitigation and prospective peak. Appl. Energy 2020, 273, 115247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogen, N.; Datta, S.; Filippini, M. Demand-side management by electric utilities in Switzerland: Analyzing its impact on residential electricity demand. Energy Econ. 2017, 64, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cai, W.; Feng, X. How do urban households in China respond to increasing block pricing in electricity? Evidence from a fuzzy regression discontinuity approach. Energy Policy 2017, 105, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Song, Z. The Effect of Building Electricity Consumption on Residents’ Subjective Well-Being: Evidence from China. Buildings 2022, 12, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Lu, Y.; Wei, K.H.; Cui, Q. Prediction of household electricity consumption and effectiveness of concerted intervention strategies based on occupant behaviour and personality traits. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 127, 109839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freier, J.; von Loessl, V. Dynamic electricity tariffs: Designing reasonable pricing schemes for private households. Energy Econ. 2022, 112, 106146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.W.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.H.; Hu, W. Exploring Increasing Urban Resident Electricity Consumption: The Spatial Spillover Effect of Resident Income. Energies 2022, 15, 4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Lu, M.L.; Wang, J.C. Direct rebound effect on urban residential electricity use: An empirical study in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.Y.; Chen, Y.L.; Hu, W.Y.; Deng, N.X.; He, W.J. Exploring the impact of temperature change on residential electricity consumption in China: The ‘crowding-out’ effect of income growth. Energy Build. 2021, 245, 111040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borge-Diez, D.; Icaza, D.; Trujillo-Cueva, D.F.; Acikkalp, E. Renewable energy driven heat pumps decarbonization potential in existing residential buildings: Roadmap and case study of Spain. Energy 2022, 247, 123481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fang, Y.; Cai, W.G.; Ding, C.; Xie, Y.P. Heating demand with heterogeneity in residential households in the hot summer and cold winter climate zone in China -A quantile regression approach. Energy 2022, 247, 123462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohler, A.; Loomis, D.G.; Marquis, Y. The Household Appliance Stock, Income, and Electricity Demand Elasticity. ENERGY J. 2022, 43, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Shimizu, D.; Palmer, J.; Terry, N. What Can We Learn from the Household Electricity Survey? Buildings 2014, 4, 737–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavousian, A.; Rajagopal, R.; Fischer, M. Determinants of residential electricity consumption: Using smart meter data to examine the effect of climate, building characteristics, appliance stock, and occupants’ behavior. Energy 2013, 55, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Kim, H. Analyzing Electricity Consumption Factors of Buildings in Seoul, Korea Using Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression. Buildings 2022, 12, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.X. Linking residential electricity consumption and outdoor climate in a tropical city. Energy 2018, 157, 734–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randazzo, T.; De Cian, E.; Mistry, M.N. Air conditioning and electricity expenditure: The role of climate in temperate countries. Econ. Model. 2020, 90, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalani, M.J.; Kalani, M. Energy cost control of LEDs considering the price of electricity and the desired lighting levels to meet the requirements of smart grids, smart cities, and unregulated energy markets. Optik 2022, 258, 168926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Lin, W.; Sun, C.W.; Zhang, D.Z. Residential electricity consumption after the reform of tiered pricing for household electricity in China. Appl. Energy 2015, 157, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, F.; Duffy, A.; Conlon, M. Characterising domestic electricity consumption patterns by dwelling and occupant socio-economic variables: An Irish case study. Energy Build. 2012, 48, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilimoakher, P.; Urmee, T.; Pryor, T.; Baverstock, G. Identifying the determinants of residential electricity consumption for social housing in Perth, Western Australia. Energy Build. 2016, 133, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ren, H.; Dong, L.; Park, H.-S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y. Smart solutions shape for sustainable low-carbon future: A review on smart cities and industrial parks in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 144, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Jordán, D.; del Río, P. Analysing the drivers of the efficiency of households in electricity consumption. Energy Policy 2022, 164, 112828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Cai, W.; Liu, W.; Wang, C. The heterogeneity in energy consumption patterns and home appliance purchasing preferences across urban households in China. Energy 2022, 253, 124079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcintas, M.; Kaya, A. Roles of income, price and household size on residential electricity consumption: Comparison of Hawaii with similar climate zone states. Energy Rep. 2017, 3, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, H.C.; Noorman, K.J.; Kok, R.; Engstrom, R.; Throne-Holst, H.; Clark, C. Pursuing more sustainable consumption by analyzing household metabolism in European countries and cities. J. Ind. Ecol. 2005, 9, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.V.; Fuertes, A.; Lomas, K.J. The socio-economic, dwelling and appliance related factors affecting electricity consumption in domestic buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 901–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; He, J.; Yang, C. Evaluating the impacts of the increasing block tariffs on residential electricity consumption in China. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Yu, Y.; Wei, C. Climatic impact on China’s residential electricity consumption: Does the income level matter? China Econ. Rev. 2020, 63, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brounen, D.; Kok, N.; Quigley, J.M. Residential energy use and conservation: Economics and demographics. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2012, 56, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.W.; Gertler, P.J. Contribution of air conditioning adoption to future energy use under global warming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5962–5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Kimura, F.; Sandu, S. Household-level analysis of the impacts of electricity consumption on welfare and the environment in Cambodia: Empirical evidence and policy implications. Econ. Model. 2020, 89, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, R.; Rosa, E.A.; Dietz, T. STIRPAT, IPAT and ImPACT: Analytic tools for unpacking the driving forces of environmental impacts. Ecol. Econ. 2003, 46, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Shen, L.; Ren, H.; Cai, W.; Ma, Z. How to Measure Carbon Emission Reduction in China’s Public Building Sector: Retrospective Decomposition Analysis Based on STIRPAT Model in 2000–2015. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, T.F.; Li, X.H.; Cai, W.G.; Zuo, J.; Jia, F.Y.; Wei, H.F. Exploring the impact of urbanization on urban building carbon emissions in China: Evidence from a provincial panel data model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 56, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.X.; Zhong, X.Y.; Cai, W.G.; Ren, H.; Huo, T.F.; Wang, X.; Mi, Z.F. Dilution effect of the building area on energy intensity in urban residential buildings. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.D.; Yan, R.; Cai, W.G. A STIRPAT model-based methodology for calculating energy savings in China’s existing civil buildings from 2001 to 2015. Nat. Hazards 2017, 87, 1765–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddle, B.; Lung, S. Revisiting energy consumption and GDP causality: Importance of a priori hypothesis testing, disaggregated data, and heterogeneous panels. Appl. Energy 2015, 142, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Luo, Z.C.; Xiao, D. Age Structure and Carbon Emission with Climate-Extended STIRPAT Model-A Cross-Country Analysis. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 9, 719168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, G.C.; Dong, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Shang, P.P. The Scale, Structure and Influencing Factors of Total Carbon Emissions from Households in 30 Provinces of China-Based on the Extended STIRPAT Model. Energies 2018, 11, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, F.; Kocak, E.; Bulut, U.; Kuloglu, A. The impact of urbanization on energy intensity: Panel data evidence considering cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity. Energy 2017, 133, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirtas, T.; Akpolat, A.G. The relationship between energy consumption, urbanization, and economic growth in new emerging-market countries. Energy 2018, 147, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-H. The determinants of household electricity consumption in Taiwan: Evidence from quantile regression. Energy 2015, 87, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkouwer, S.B. Electric Heating and the Effects of Temperature on Household Electricity Consumption in South Africa. Energy J. 2020, 41, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Guo, Q.; Smyth, R.; Yao, Y. Extreme temperatures and residential electricity consumption: Evidence from Chinese households. Energy Econ. 2022, 107, 105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, E.; Lyons, S. Energy use and appliance ownership in Ireland. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 4265–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.Q.; Chen, X. Is the implementation of the Increasing Block Electricity Prices policy really effective?—Evidence based on the analysis of synthetic control method. Energy 2018, 163, 734–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paco, A.; Lavrador, T. Environmental knowledge and attitudes and behaviours towards energy consumption. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 197, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | Variable | Variable Name | Type | Source of Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | E | Urban household electricity consumption | Explained variable | China Energy Statistical Yearbook |

| Demographic factor | FSIZE | Average family size (person/household) | Explanatory variable | China Statistical Yearbook |

| ELDER | Presence of elderly people | Explanatory variable | China Statistical Yearbook | |

| Economic factors | PGDP | Per capita gross domestic product | Explanatory Variable | China Statistical Yearbook |

| Urbanisation | U | Urbanisation level in China | Explanatory variable | China demographic and employment statistics yearbook |

| Household appliances | AC | Air conditioner per household | Explanatory Variable | China Statistical Yearbook |

| TV | Colour TV per household | Explanatory variable | China Statistical Yearbook | |

| Floor area | F | Floor area per capita | Explanatory variable | City statistical yearbooks |

| Temperature | CDD | Cooling degree days | Explanatory Variable | National Weather Service China |

| HDD | Heating degree days | Explanatory Variable | National Weather Service China |

| Ln (FSIZE) | Ln (PGDP) | Ln (U) | Ln (AC) | Ln (TV) | Ln (F) | Ln (CDD) | Ln (HDD) | Ln (OLD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ln (FSIZE) | 1 | ||||||||

| Ln (PGDP) | −0.635 *** | 1 | |||||||

| Ln (U) | −0.705 *** | 0.885 *** | 1 | ||||||

| Ln (AC) | −0.311 *** | 0.433 *** | 0.422 *** | 1 | |||||

| Ln (TV) | −0.243 *** | 0.120 *** | 0.231 *** | 0.566 *** | 1 | ||||

| Ln (F) | −0.113 ** | 0.455 *** | 0.221 *** | 0.425 *** | 0.234 *** | 1 | |||

| Ln (CDD) | −0.084 * | 0.253 *** | 0.297 *** | 0.800 *** | 0.577 *** | 0.438 *** | 1 | ||

| Ln (HDD) | −0.266 *** | −0.00200 | 0.0130 | −0.440 *** | −0.269 *** | −0.304 *** | −0.613 *** | 1 | |

| Ln (OLD) | −0.198 *** | 0.080 * | −0.0440 | 0.538 *** | 0.338 *** | 0.332 *** | 0.328 *** | −0.086 * | 1 |

| Model (LnE) | Coefficients | Std. Error | P > |t| | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | −10.514 | 0.705 | 0.000 | 0 | 0 |

| Ln (FSIZE) | −0.137 | 0.157 | 0.384 | 0.356 | 2.81 |

| Ln (PGDP) | 0.452 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 0.111 | 9.03 |

| Ln (U) | 0.593 | 0.134 | 0.000 | 0.106 | 9.45 |

| Ln (AC) | −0.040 | 0.017 | 0.023 | 0.201 | 4.97 |

| Ln (TV) | 0.221 | 0.088 | 0.013 | 0.543 | 1.84 |

| Ln (F) | 0.371 | 0.083 | 0.000 | 0.455 | 2.20 |

| Ln (CDD) | −0.048 | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.221 | 4.52 |

| Ln (HDD) | −0.134 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.502 | 1.99 |

| Ln (OLD) | 0.878 | 0.019 | 0.000 | 0.470 | 2.13 |

| Test Summary | Chi-Sq. Statistic | Chi-Sq. d. f. | Prob. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Cross-section random | 62.622 | 9 | 0.000 |

| Model (2) | Cross-section random | 52.848 | 7 | 0.000 |

| Variable | Model (1) | Model (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Ln (U) | 0.671 *** (5.627) | 0.657 *** (5.520) |

| Ln (PGDP) | 0.515 *** (15.628) | 0.535 *** (17.618) |

| Ln (HDD) | −0.106 *** (−2.497) | −0.113 *** (−2.674) |

| Ln (OLD) | 0.286 *** (4.841) | 0.315 *** (5.520) |

| Ln (TV) | −0.182 (−1.572) | |

| Ln (FSIZE) | −0.367 *** (−3.738) | −0.383 *** (−3.910) |

| Ln (F) | 0.152 *** (2.682) | 0.149 *** (2.624) |

| Ln (CDD) | 0.007 (0.889) | |

| Ln (AC) | −0.065 *** (−2.258) | −0.073 *** (−2.580) |

| C | −4.079 *** (−4.3355) | −5.202 *** (−8.333) |

| Adjust R2 | 0.985 | 0.985 |

| F | 776.553 | 816.978 |

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| DW | 0.471 | 0.480 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Cai, W.; Hou, L.; Zhou, Z.; Bian, J. Examining the Provincial-Level Difference and Impact Factors of Urban Household Electricity Consumption in China—Based on the Extended STIRPAT Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9960. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169960

Wang Y, Cai W, Hou L, Zhou Z, Bian J. Examining the Provincial-Level Difference and Impact Factors of Urban Household Electricity Consumption in China—Based on the Extended STIRPAT Model. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):9960. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169960

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yuanping, Weiguang Cai, Lingchun Hou, Zhaoyin Zhou, and Jing Bian. 2022. "Examining the Provincial-Level Difference and Impact Factors of Urban Household Electricity Consumption in China—Based on the Extended STIRPAT Model" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 9960. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169960

APA StyleWang, Y., Cai, W., Hou, L., Zhou, Z., & Bian, J. (2022). Examining the Provincial-Level Difference and Impact Factors of Urban Household Electricity Consumption in China—Based on the Extended STIRPAT Model. Sustainability, 14(16), 9960. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169960