Abstract

The academic evaluation of teachers of languages other than English (LOTEs) has been extensively researched, especially from the perspective of academic publications. However, little attention has been paid to another key performance indicator in teacher assessment, namely, external research funding. Focusing on German language teachers (GLTs), this paper adopts a mixed methods approach to investigate the assessment requirements for LOTE teachers in terms of external research funding and the factors that may impact their accomplishments. Based on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory and conservation of resources theory, we analyzed policy documents from the universities under investigation, examined “German or Germany-related” funding approvals, and conducted semi-structured interviews with eight GLTs to explore the environmental factors (individual context, institutional context, social context, chronological context) that may influence the survival of GLTs in terms of the requirements for external research funding. The findings indicate that factors from each ecological context interact with one another and have a combined influence on GLTs’ external research funding application activity. Moreover, there is an imbalance between the academic demands faced by GLTs and the resource support that is available to them. This imbalance may affect the survival and development of GLTs and is likely to have a continuing influence throughout their career. The study concludes by offering some suggestions at different levels to facilitate the sustainable professional development of GLTs.

1. Introduction

In the quest to develop world-class universities in China [,], “governments promote aggressive management practices to ensure that their universities do well in research and academic quality assessment” [] (p. 554). Consequently, research performance evaluation in relation to employment decisions has a significant impact on the recruitment of talents to universities and their subsequent career development []. Academic outputs are increasingly emphasized in performance evaluation and the university employment system in higher education, and in this context, scholars in the Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) may be more vulnerable within university assessment mechanisms compared to researchers in the hard sciences [,]. The reason is that HSS research is generally underrepresented in the rankings of universities, and “the bibliometric indicators and field-normalised citation counts” cannot totally capture the contributions of HSS researchers [] (p. 18).

To date, the impact of research performance evaluation on the career development of university academics has been examined in a number of studies [,]. However, much of the existing research has focused on academic publications, with little attention paid to requirements for securing external research funding. Due to the role of research income in ranking exercises for universities, research funding is an increasingly important criterion in university academics’ promotion and career development in many contexts [].

Unfortunately, university academics around the world are threatened with funding cuts, and this is particularly true for social science researchers since governments often favor hard science research in their funding allocation decisions []. As a result, obtaining external research funding is a particular stumbling block in the career development of university academics in HSS disciplines. Among these, teachers of languages other than English (LOTEs) are likely to be even more marginalized and experience more significant challenges because their research productivity is relatively low in comparison with researchers in other HSS disciplines []. To date, only a small body of research has focused on the significance of external research funding in the assessment of academic performance in this area, except for a couple of bibliometric analysis studies [,].

As one of the most important research programs in philosophy and social science in China, the National Social Science Fund of China (NSSFC) is seen as a benchmark for external research funding, and attempts to obtain NSSFC funding may determine the career development trajectories of LOTE teachers. In practice, the number of NSSFC projects obtained by a university is often adopted as a metric to indicate its strength in social science research, even in the national university rankings. As a result, the NSSFC is highly regarded by universities and academics [].

In this study, we attempt to examine the impact of research performance evaluation on LOTE teachers by focusing on German language teachers’ (GLTs) challenges in Chinese universities. To this end, this study focuses on two research questions:

- What expectations and realities do GLTs need to respond to when applying for external research funding in Chinese universities?

- Which factors influence GLTs’ applications for external research funding?

2. LOTE Teacher Development in Chinese Higher Education

Due to the rise of English as the most important language for learning and teaching in many contexts [,], LOTE education in universities in many countries is witnessing a downward trend []. In most contexts worldwide, LOTE education is facing funding cuts []. Bucking this trend, however, the introduction of the national “Belt and Road” initiative in 2013 prompted Chinese universities to invest more resources in LOTE education, with many beginning to offer majors or courses in the languages of the countries along the “Belt and Road” []. In addition, in 2015, the Ministry of Education (MOE) issued the “Implementation Opinions on Strengthening the Education of Less-Commonly-Taught Foreign Language Talents”, and by 2016, the total number of European language majors in Chinese universities nationwide reached 114 []. However, English is still the most important foreign language in Chinese language education [], and the scale of LOTE majors is relatively small in terms of faculty sizes [].

Meanwhile, Chinese universities have been reforming their personnel systems to improve their academic output efficiency in order to become world-class universities []. Many Chinese universities have adopted the tenure-track system for the appointment and retention of lecturers, assistant professors, and associate professors. This system requires new appointees to achieve promotion within a maximum of two terms (each usually lasting three years), with the consequence that they will not be retained if they are not promoted within the specified time []. These universities have also introduced quantitative performance evaluation measures, generating significant challenges for early career university academics in terms of their research productivity []. In many universities, early career academics need to publish a specified number of indexed journal publications and secure particular amounts of research funding if they wish to get promoted and secure their long-term university employment [].

In such a context that emphasizes quantifiable research outputs and research performance indicators, foreign language teachers are facing enormous challenges in their career development as they do not do enough research and have sufficient research outputs []. Studies on foreign language teachers’ research practices have identified two categories of factors in relation to their research productivity: external factors and internal factors. The former includes peer influence and the school and social environment, while the latter includes motivation, professional identity, and reflection [,].

LOTE teachers in Chinese universities usually have a heavy teaching load and are also expected to conduct research []. However, in dealing with the conflict of identities between “teacher” and “researcher” [], they experience greater challenges in academic publishing compared to English language teachers []. On the one hand, Chinese journals in the field of foreign language teaching have an implicit ‘researching about English’ policy that “consigns the smaller groups [LOTE teachers] who do not research ‘about’ English to a peripheral position in the non-Anglophone context” [] (p. 126). On the other hand, it is also difficult for LOTE teachers to publish in indexed international journals that often use English as the medium of publication []. However, research output plays a large part in successfully obtaining external research funding, and as a result, LOTE teachers find themselves at a serious disadvantage in external research funding applications due to their low research productivity. To this end, LOTE teachers have been trying new approaches of international publication and solving their career development challenges by participating in multilingual academic communities [] and actively seeking cross-linguistic collaboration [].

Researchers have already explored LOTE teachers’ professional development focusing on academic assessment and publications [,]. However, little attention has been paid to the other key indicator, external research funding [,], and therefore a focus on the external research funding applications of LOTE teachers may provide new insights related to the challenges that these teachers from a non-English background have to face and the factors that may help them to get over this stumbling block.

3. Theoretical Framework

In this study, we draw on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory [] and the conservation of resources (COR) theory [] to explore how GLTs respond to the challenges in securing external funding for academic promotion in Chinese universities. Bronfenbrenner [] views a person’s development as a complex system of relationships affected by multiple levels of the surrounding environment; according to this definition, the environment for the professional development of teachers is the world in which teachers live—that is, the environment in which they perceive and experience their professional life and growth.

In Bronfenbrenner’s theory, there are five sub-systems based on the surrounding environment, i.e., the microsystem, the mesosystem, the exosystem, the macrosystem, and the chronosystem [,]. The microsystem is “a pattern of activities, roles, and interpersonal relations experienced by the developing person in a given setting with particular physical and material characteristics” [] (p. 22). The mesosystems are primarily concerned with the interactions between individual microsystems. Next, the exosystem comprises “one or more settings that do not involve the developing person as an active participant, but in which events occur that affect, or are affected by, what happens in the setting containing the developing person” [] (p. 25). The macrosystem is the “consistencies, in the form and content of lower-order systems (micro-, meso-, and exo-) that exist, or could exist, at the level of the subculture or the culture as a whole, along with any belief systems or ideology underlying such consistencies” [] (p. 26). Finally, the chronosystem is “the influence on the person’s development of changes (and continuities) over time in the environments in which the person is living” [] (p. 724). These five ecological systems interact with one another and work together to impact GLTs.

“Every occupation may have its own specific working characteristics” [] (p. 323). The characteristics of all working environments can be classified into two general categories, namely, job demands and job resources []. According to the COR theory, resources do not exist individually; instead, they are intimately tied to one another ecologically []. Because of dynamic changes over time, resources can have different effects depending on the environment and conditions. People “with greater resources are less vulnerable to resource loss and more capable of resource gain” and vice versa, contributing to effects such as “loss spirals” and “gain spirals” [] (p. 106). Job demands and resources in a particular occupational context do not correspond to only one of Bronfenbrenner’s five environmental systems; rather, they interact with several of them.

The occupation of GLTs has its own specific working features. The process of GLTs’ career development is constrained by multiple environments, each comprising requirements and resources from different levels []. According to COR theory, the pursuit of goals is dynamic and there is a strong relationship between resources []. Therefore, the requirements and resources faced by GLTs are not independent; rather, they interact with each other and change over time. We condensed Bronfenbrenner’s multiple layers of interwoven contextual structures into three core levels, i.e., individual context, institutional context, and social context, complemented by the chronological context, to form the theoretical framework for this study (see Table 1). Within this theoretical framework, the GLTs’ developing context is viewed as an organic ecosystem consisting of nested environmental elements that interact with each other and influence the GLTs’ professional development.

Table 1.

The contexts for GLTs’ career development.

4. The Study

To address the research questions, we collected multiple data from different sources using a mixed methods approach. First we recruited eight Chinese GLTs from five universities and collected policy documents from each university. Then, we extracted information on “German or Germany-related” external research funding from the NSSFC database and from the National Office for Philosophy and Social Science (NOPSS). Third, we conducted semi-structured interviews with the eight participants, focusing on external research funding requirements for promotion, the challenges they experienced in making external research funding applications, and possible ways to address these challenges.

4.1. Participants

Focusing on research pressure among GLTs, we recruited our research participants through purposive sampling and snowball sampling from five universities. All of these five universities are comprehensive, key universities in China (four are Project 985 universities, and one Project 211), two located in northern, two in central-western, and one in eastern China. Among these five universities, four have German departments, and one has a German unit under the European department (it includes four units, i.e., German, French, Russian, and Spanish). All of these departments are under the unified administration of the School of Foreign Languages or the School of Translation, implementing unified standards for teacher recruitment, performance assessment, and promotion. All participants were lecturers or associate professors who were either on a tenure track or who were facing the challenge of a higher professional title evaluation.

As shown in Table 2, five of the participants were lecturers and three were associate professors. Five had obtained their PhD degrees in Germany and two in China, while the only MA lecturer was pursuing his PhD degree in China. All of the newly enrolled teachers (i.e., those aged between 30 and 34) were on a tenure track, indicating the establishment and prevalence of this evaluation system in Chinese universities in recent years.

Table 2.

Demographic information about the participants.

4.2. Data Collection and Analysis

To represent the requirements and situation related to external research funding applications among GLTs, we first collected policy documents from each sampled university (either retrieved from open-access resources or provided by the participants). Then, we extracted information about “German or Germany-related” funding from the NSSFC database (1991–2020) (http://fz.people.com.cn/skygb/sk/index.php/Index/index, 27 October 2021) and from the NOPSS (http://www.nopss.gov.cn/GB/index.html, 27 October 2021). The NSSFC, established in 1991, is the main funding source supporting basic scientific research in China. Based on the NSSFC database, we first extracted information about “German or Germany-related” funding, then conducted a manual check to ensure that the external research funding applications were by GLTs. A final sample of 69 national-level funding applications during the period from 1991 to 2020 formed our database.

Based on our analysis of the policy documents and the results related to national-level funding applications, semi-structured interviews were conducted with the participants. The questions focused on three core aspects, i.e., the participants’ external research funding requirements for promotion, the challenges they experienced during the funding application, and possible ways in which they addressed these challenges. The interviews were conducted in Mandarin Putonghua, audio-recorded with the permission of the participants, and lasted for about 60 min on average. The interview recordings were then transcribed and proofread by the authors.

5. Results

This section presents the research requirements placed on GLTs by Chinese universities if they want to achieve promotion and the realities of national-level funding approvals for GLTs. After that, factors that influence GLTs’ funding applications are discussed.

5.1. The External Research Funding Requirements for GLTs’ Promotion

5.1.1. High Expectations Placed on GLTs by Universities

To obtain a promotion, GLTs have to meet minimum promotion requirements during the academic performance evaluation process as implemented by their respective university. The basic requirements for all the participants are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Minimum promotion requirements for academic evaluation.

Table 3 shows that both publications and external research funding are essential in academic evaluation for university academics to get promoted. Moreover, some universities have specific requirements in terms of citation indexes, such as the SSCI or A&HCI. These publication requirements create significant pressures and challenges for teachers, who already have heavy teaching loads and other service obligations at the same time [].

As for the other key performance indicator, namely, external research funding, in all five sampled universities GLTs are expected to obtain funding for at least one provincial or ministerial-level project in order to be promoted to the level of associate professor. To be promoted to a full professorship, one successful national-level funding application is the minimum requirement. In addition, some of the sampled universities seem to have higher requirements for promotion. For instance, University E requires one national-level funding allocation or two successful provincial or ministerial-level project funding applications when applying for an associate professorship and one national plus two provincial or ministerial-level funded projects (which should not only be approved but also finished) for a full professorship.

5.1.2. The Distribution of External Research Funding Granted to GLTs

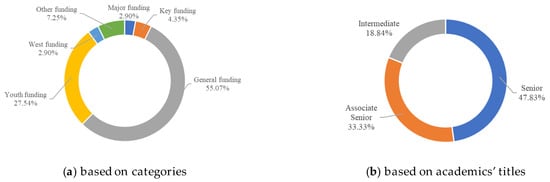

After reviewing the requirements for promotion to a professorship for Chinese GLTs, it is necessary to work out how many NSSFC funding allocations have actually been granted to GLTs. To answer this question, we examined the distribution of the 69 successfully funded “German or Germany-related” projects identified through the procedures described in Section 4.2 in terms of their different categories and titles, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proportional distribution of the 69 funding allocations based on categories and academics’ titles.

There are five major funding categories: major funding (established through public bidding; applicants should be professors), key funding (intended to solve important issues or problems; applicants should be associate professors or PhD holders), general funding (applicants should be associate professors or PhD holders), youth funding (applicants should be younger than 35 years), and western funding (applicants should be from less developed regions). Figure 1 shows that general funding accounts for 55.07% of all the “German or Germany-related” funding allocated, and youth funding makes up another 27.54%. Taken together, these two categories account for a high proportion, more than 80% of all the funding. This is in parallel with the wider situation for the types of funding granted to foreign language teachers and social scientists in general [].

In addition, almost half of the approved funding (47.83%) was granted to senior researchers (the equivalent of full professors), 33.33% to associate senior researchers (equivalent to associate professors), and only 18.84% to intermediate researchers (equivalent lecturers and assistant professors). Generally, newly recruited GLTs under a tenure track are classed as intermediate researchers who are not likely to have many academic outputs, while applicants with higher titles have had more chances to accumulate publications. Hence, it is not surprising that senior researchers account for the largest proportion of the funding allocated.

5.2. Factors Contributing to GLTs’ External Research Funding Applications

In this section, we consider the factors that influence GLTs in managing the requirements for external research funding through an analysis of the semi-structured interviews. The specific analysis was preceded by a brief overview of the interviewees’ successful research funding applications. Two of the eight interviewees (P2 and P6) were awarded the NSSFC, and they undertook a western funding project and a sub-project of a major funding project (equivalent to a general funding, but not an independent funding application). P2 was a lecturer at the time of funding application and was promoted to associate professor after receiving the NSSFC funding. The funding was granted to P2 after she changed her research direction from foreign literature to interdisciplinary research on foreign literature and Chinese literature. P6, an associate professor for many years, is the oldest interviewee, who has accumulated extensive experience in the field of German literature and has been designated as the leader of a sub-project of a major funding. The remaining six interviewees all had experience in applying for fundings.

Based on the GLTs’ developing context structures proposed in Section 3 and the participants’ own experiences, we identify factors at four levels, i.e., individual context, institutional context, social context, and chronological context.

5.2.1. Individual Context: Conflict of Multiple Roles and Academic Competence Shortage

The factors in the individual context can be classified into two general types, namely, lack of time and lack of prior publications. Most of the GLTs are fulfilling multiple roles, not only acting as teachers, but also managing service obligations, academic requirements, etc. Among these multiple roles, their teaching workloads were the most commonly mentioned. For instance:

This is difficult for everyone. I think we have quite a lot of classes, especially for me. In my case, the minimum teaching time is 8 h per week. Sometimes I even have to teach for more than 20 h a week, depending on my situation.(Interview with P7)

According to P7, almost every GLT’s teaching time exceeded what he/she was contractually required to do. Moreover, all of the young GLTs expressed that they also needed to meet a number of service obligations (e.g., counselor, teaching secretary). On top of the prep time required for their lessons and their service obligations, all eight participants reported that preparing a funding proposal was a time-consuming process. They felt they would need at least two months to prepare a funding proposal, with some stating that they would need half a year or even a whole year to complete their funding proposal preparation, from the selection of a topic to completing and submitting the application. In this sense, their extraordinary teaching burdens and service obligations constrain the participants’ endeavors to carry out research.

Apart from their lack of time, all participants expressed concern about their lack of prior publications. In particular, the GLTs who had obtained their PhDs in Germany had no mandatory requirements for publication during their doctoral studies. As a result, most of them lacked awareness and experience of journal article publishing.

The difficulty was that I personally didn’t accumulate enough publications—that is, my prior publications were so poor. I didn’t know the domestic assessment situation. I always thought about writing my final thesis during my PhD, and I didn’t even think about publishing more articles. I think that the German [education system] in general doesn’t see article publication as [important], and there are no rules about the level of publications—for example, what kind of article counts and what kind of article doesn’t.(Interview with P4)

P4 was a young GLT who had received his PhD in Germany. He did not consider the importance of journal article publication during his doctoral studies because there is no mandatory requirement to do so in German universities. Instead, he focused on his thesis. However, when P4 was recruited as a college teacher in China, he found that publications play a decisive role in both academic assessment and external research funding applications. A scholar’s previous publication record and the level of these publications are seen as the external manifestation of the applicant’s academic ability, based on which assessors are able to judge whether the applicant can undertake the project []. A lack of prior publications can therefore be a major impediment to funding applications.

5.2.2. Institutional Context: Growing Research Pressure and Inefficient Organizational Support

The most frequently mentioned factors in the institutional context can be summarized as the increasing emphasis on research, differential selection in the funding application, and inefficient centralized tutorials. As discussed in Section 5.1, to meet the threshold for promotion, GLTs need not only to publish papers, but also to receive external research funding. This means that GLTs have to cope with overt measurement of research performance and outcomes while also managing a high teaching workload. Moreover, this increasing emphasis on research is accompanied by an increase in recruitment requirements. More than one participant mentioned that it is becoming very difficult to recruit new teachers due to the high recruitment thresholds:

We are in an overloaded [work] state now, with a very small number of teachers and a lot of work. It is too difficult for us to recruit people. Last time our department was asked to recruit associate professors from other universities directly [rather than new PhD graduates]. Moreover, they [i.e., PhD graduates majoring in science and engineering] had all published [many] articles. PhD graduates [in our department] obviously cannot meet that requirement. That’s maybe why it is so difficult to recruit new teachers.(Interview with P4)

This increase in the recruitment threshold directly contributes to the shortage of GLTs, which interacts with the individual context and means that most of the GLTs have a heavy teaching burden. Moreover, all participants also reported that their universities require teachers to apply to the NSSFC for funding, which means that all teachers who are eligible to apply to the NSSFC are required to do so:

Universities require teachers to submit NSSFC proposals, but this does not mean the proposals will be submitted to the NOPSS committee. There is a series of selection procedures. However, it seems to be an obligation for teachers to submit a proposal, no matter whether it will be submitted to the NOPSS committee or not. If you do not submit, you are likely to be approached by the faculty head and be asked why you didn’t submit anything.(Interview with P5)

Although universities require teachers to submit as many applications as possible, not all funding proposals can be submitted to the NOPSS committee since each university is only allowed to submit a limited number of NSSFC applications. This selection mechanism encourages the universities to employ selection procedures to pick the best proposals, but it also means that most proposals are not submitted to the NOPSS committee to be reviewed or evaluated.

In addition, all of the sampled universities organized NSSFC application mobilization meetings or tutorials, inviting experts to share their funding application experiences or comment on applicants’ funding proposals. However, some participants gave negative feedback about these sessions, especially in relation to the activities organized by universities. For instance, in P6’s university, the invited experts were not intradisciplinary (i.e., from the areas of foreign languages and literature). The writing paradigms for funding proposals in different disciplines vary significantly, but proposals will be ultimately reviewed and evaluated by intradisciplinary experts on funding decision panels. Accordingly, it is not so helpful to invite experts from other disciplines to give their advice.

5.2.3. Social Context: Higher Education in Transformation and LOTE in Marginalization

This context involves two key factors, namely, the reform of the personnel system in higher education institutions and the dominance of English in the academic publishing market. As part of the reform of personnel systems in Chinese higher education, universities implemented further reforms of their personnel recruitment systems [], changing their personnel practices from the traditional promotion system to the tenure track system []. All of the newly enrolled participants were under a tenure track, indicating the rapid establishment of this personnel system in China in recent years (see Table 2). However, these young GLTs expressed their doubts about this personnel system, which is often called the “up or out” rule in China []. For instance:

[This system] does not make sense. How can I put it? Maybe it’s because our discipline is quite special, to some extent. Now that we have adopted the “up or out” personnel system, could the teaching workload be reduced a little bit? There is still a big teaching burden on teachers who need to produce so many academic outputs in a short period of time. The university should be aware that there is a gestation process for academic outputs. It is really difficult for many teachers to get so many papers published in such a short time.(Interview with P5)

As a newly enrolled teacher on a tenure-tracked path, P5 was aware of the unreasonableness of this system for HSS disciplines. Compared to teachers of science and technology, it is more difficult for GLTs to fulfill not only their excessive teaching burden but also harsh academic requirements during their tenure assessment. Young GLTs have to apply for funding to preserve their academic positions, and they have to succeed. However, GLTs who are not employed under the “up or out” personnel system do not face such heavy pressure or need to compete for tenure positions; they still have the luxury of being able to fail, and they can choose to remain at the rank of lecturer or associate professor until their retirement.

As noted above, having insufficient prior publications is a major impediment to funding applications. However, all participants mentioned that in academia it is difficult for GLTs to get their articles published since their academic languages are generally German or Chinese:

I think it is more difficult for LOTE teachers to publish articles than for English language teachers (ELTs). This is because in China, the field of language and literature is mainly dominated by English majors. I think that the research and writing methods used by LOTE teachers are very different from their requirements, habits, or preferences. Compared to ELTs, LOTE teachers are too weak to be competitive [in publishing].(Interview with P7)

Under the “efficiency-oriented” academic context [], both LOTE teachers and ELTs need to complete increasing numbers of performance evaluations. However, publishing about LOTEs in the Chinese market is not easy, as the Chinese publishing market pays great attention to the impact factor of journals []. Hence, we were curious about whether our GLTs had tried to publish in international indexed journals. Most of the participants confirmed their awareness that the English language plays a dominant role in the international publishing market [,], and there are discrepancies in research paradigms regarding different languages. It was difficult for them to improve their language skills and enter the international publishing market in such a short time.

5.2.4. Chronological Context: Ever-Changing Research Trends and Inadequate Track Records of Prior Research

In the chronological context, the most frequently mentioned factor influencing GLTs’ external research funding applications was the annual adjustment of research topics. Every year, the NOPSS releases the NSSFC Guide, which details the major theoretical and practical topics or issues that the country needs to solve, providing a basis and guidance for applicants to draft their proposals. The scope of the topics covered is contemporary, political, regional, and national []. For example, in recent years, hot topics include the “Belt and Road” initiative, the New Liberal Arts Construction, and so forth. As a result, applicants who have failed in previous applications may attempt to adopt new topics or adjust prior topics to fit the Guide in that year. However, the reorientation of one‘s research needs a new process of knowledge learning and publication accumulation, which would not happen overnight. Therefore, most teachers, especially older faculty members, indicated that they would stick to their research topics:

I will keep going and carry on. One of my colleagues submitted proposals on the same topic for two or three years and finally won the NSSFC this year. I applied for funding several years ago, then I did not apply in the next year, and then I applied again with the same research topic. I am sticking to my own research interest, because I think that the suggested topics given by the NOPSS will always change, and I can’t keep up with the pace of change. Without research accumulation, there are no preliminary accomplishments, I mean, publications. So it’s not like I can just change my research topic whenever I want to.(Interview with P6)

P6 felt that although the NSSFC Guide was useful in listing the hot topics each year, guiding applicants in their selection of topics, it would be unwise to blindly follow these topics. The reason for this was that if applicants were not familiar with the relevant field, or lacked relevant prior publications in that field, the quality of their funding proposal would not be guaranteed.

Moreover, we found that the research items listed in the NSSFC Guide were general directional entries, especially the topics under the category of foreign literature (e.g., “studies of Chinese translations of foreign literary works”). Through a further observation of the NSSFC Guides from 2010 to 2022, we found that among the 1961 designated area items and research direction items under the categories of international studies, foreign literature, and linguistics, only seven were “German or Germany-related”. This may be the reason why most of our GLTs tended to choose self-selected topics for their funding proposals rather than following the designated area items or research direction items listed in the NSSFC Guide.

6. Discussion

Based on ecological systems theory and COR theory, we have summarized a four-level developing context structure for GLTs that consist of the individual context, the institutional context, the social context, and the chronological context; this structure provides a clear framework for analysis. Our findings indicate that GLTs have to successfully apply for a certain amount of external research funding to be promoted and secure their long-term employment. The various factors in each ecological context are interconnected with each other, and together they have a clear impact on GLTs’ funding applications.

From the individual perspective, COR theory suggests that individuals who have greater initial resources are more likely to experience resource gain []. In this regard, when GLTs have more resources, they are more likely to be successful with their funding applications. Prior academic publications are heavily weighted in successful funding applications [,], meaning that applicants with more prior publications have a greater chance to succeed. Applicants with higher titles generally have a better accumulation of publications, and therefore GLTs with senior titles may be at an advantage in the competition for external research funding.

Moreover, LOTE teachers have fewer resources for publication than ELTs []. English is the dominant language in the academic communication ecosystem [,]. It is difficult for GLTs to improve their language skills and produce recognized research outputs over the short terms specified by their tenure track. Meanwhile, the writing of a proposal in itself is a long and intensive process, requiring significant effort and time to produce a polished funding proposal to maximize the applicants’ chance of success in the competition. However, GLTs are caught in a dilemma, with multiple roles interacting with each other throughout their professional lives. Therefore, when GLTs’ personal resources cannot keep up with the requirements of their universities, GLTs will face further resource loss.

In the institutional context, the universities have strengthened the performance evaluations of their employees, complemented by a sharp increase in the thresholds for recruitment under the “double first-class” construction [,]. As a result, it is difficult to recruit new employees, particularly young teachers who are qualified for vacant positions but who may lack relevant experience or research records, leading to an extraordinary teaching burden for existing GLTs.

In addition, GLTs not only lose the autonomy and choice about whether to submit a proposal, but also may not have access to the appropriate resources to have their proposals reviewed. Increased work requirements are not always accompanied by an increase in resources, which has led some GLTs to be reluctant to write funding proposals and fulfill this requirement only passively []. Our findings do indicate that universities have offered some support for teachers’ funding applications by inviting experts who have succeeded in obtaining NSSFC funding in the past. However, the GLTs’ overall feedback on these mobilization meetings was that they were not always satisfactory. In other words, universities are failing to provide adequate and effective resources for GLTs’ sustainable development, despite the high demand for employment.

At the social level, the reform of the personnel systems of higher education institutions driven by the government has led universities in China to change their personnel practices from traditional promotion systems to the tenure track. Our findings confirm the rapid establishment and spread of this system in China in recent years. Hence, GLTs under a tenure track have to work hard to submit proposals to achieve a professorship and retain their position at their existing institution.

As mentioned earlier, prior publications are highly significant in the success of funding applications, but the overall academic environment is still dominated by English [,]. Our findings confirm that in the publishing market there is an implicit tendency that favors publishing in and about English [], which further disadvantages GLTs. In all, the employment environment resulting from the overarching personnel reform and the academic environment in which English is the dominant language both create significant barriers to GLTs’ sustainable professional development.

From the perspective of the chronological context, GLTs who fail in their NSSFC applications must negotiate a change in research topic for the following year’s submission. Each year the NOPSS issues the NSSFC Guide to the major theoretical or practical issues that the country needs to address, guiding applicants on the direction and scope of their research. However, our findings indicate that in GLTs’ general research fields (i.e., international studies, foreign literature, and linguistics) “German or Germany-related” items are rarely listed as a priority. As a result, most GLTs tend to choose self-selected topics for their funding proposals.

We also found that the research items listed in the NSSFC Guide under the category of foreign literature tended to be general research directions in earlier years, but recently the items have become more specific. To some extent, this reflects an improvement in the specification of the NOPSS policy. However, due to the GLTs’ lack of personal resources, most of them reported that they would stick to their original research topic. In this regard, the age and professorship of the faculties also play an important role. Although associate professors are also under pressure for promotion, they were not employed under the “up or out” rule and can find a balance between funding orientation and personal interests. Senior academics show a greater propensity to protect the resources they already own (e.g., previous proposals) and to reduce the action of investment (e.g., writing new proposals) so as to protect against further loss [].

All of these levels of ecological context interact with each other and influence GLTs’ sustainable professional development [,]. In each system, the factors that influence GLTs’ funding applications can be seen essentially as the result of an imbalance between requirements and resource support, and they all interact and impact GLTs’ external research funding applications []. In the process of preparing and submitting funding applications, different levels of ecological context are available to provide resource support to GLTs. However, in general, the resource support available to GLTs is still far from adequate. Although the pressure to apply for funding varies among GLTs who are employed under different personnel systems, it is undeniable that the requirement for performance evaluation and promotion is closely related to the survival and development of GLTs and has a continuing influence throughout their career.

7. Conclusions

Through an analysis of university policy documents, database evidence, and semi-structured interviews with eight GLTs from sampled universities in China, we found that GLTs have to successfully apply for a certain amount of research funding within a particular period in order to achieve promotion. However, the reality is that only a small amount of funding is granted to GLTs. Through the lens of ecological systems theory and COR theory, we have summarized GLTs’ developing context structures (i.e., individual context, institutional context, social context, and chronological context) to identify the factors that influence GLT’s external research funding application activity.

GLTs’ career development is a systemic project influenced by four dimensions. The current study has found an imbalance between the academic demands faced by GLTs and their available resource support. Adequate resource support is essential for GLTs’ professional development and can motivate teachers to pursue growth and development []. However, the support provided from different dimensions is generally inadequate. Therefore, effective strategies should be put in place at different levels to help GLTs to engage in and maintain their sustainable professional development.

At the individual level, GLTs need to maintain and improve their English language proficiency and academic capacity, consciously seeking collaborators and cooperation to build their own academic circle, so as to accumulate publications for funding applications and promotion. The more researchers collaborate with others, the more access to resources they may have []. At the institutional level, universities should pay more attention to the professional development of GLTs and provide more support. This is because the tenure track is not only a “probation period” for universities to examine young teachers, but also a “nurturing period” to motivate their growth through the provision of resources []. Such support may be diverse; for instance, universities should provide more adequate and higher-level resource support than the provision of inefficient centralized tutorials. At the social level, optimizing the academic labor market and remaining vigilant to the “privilege” of English in the academic market [,] are two possible aspects that could improve the healthy development of GLTs, perhaps by measures such as promoting a more comprehensive journal assessment system or founding multilingual journals.

Generally speaking, GLTs’ professional development is a process of constant change over time. In this process, the various ecological contexts interact with each other to promote GLTs’ sustainable development. By paying special attention to GLTs, the current research explores the assessment of academic performance in terms of external research funding; this has rarely been investigated, particularly in the context of LOTEs. Based on the four contextual levels, we explored GLTs’ developing context structures, providing a clear analytical framework for research on the professional development of LOTE teachers. We propose suggestions at the individual, institutional, and social levels to facilitate a balance between requirements and resource support, thereby paving the way for more systematic and healthier professional development for LOTE teachers in China.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.S., Y.C., S.L. and X.G.; Original draft preparation: S.L.; Data collection and analysis: S.L. and Y.C.; Supervision and review: X.G. and Q.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by Research Ethics Committee of the School of Foreign Languages, Tongji University (protocol code tjsflec202106).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgments

Our sincere thanks go to the participants who joined our interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yang, R.; Welch, A. A World-Class University in China? The Case of Tsinghua. High. Educ. 2012, 63, 645–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Patton, D.; Kenney, M. Building Global-Class Universities: Assessing the Impact of the 985 Project. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zheng, Y. ‘Heavy Mountains’ for Chinese Humanities and Social Science Academics in the Quest for World-Class Universities. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2020, 50, 554–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, J. Surviving the Performance Management of Academic Work: Evidence from Young Chinese Academics. High Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 704–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Gao, X. The Ecology of Language in International Academic Publishing: A Case Analysis of Chinese Scholars’ Publications. Foreign Lang. China 2016, 13, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Rauhvargers, A. Global University Rankings and Their Impact Report II; European University Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Sit, H.; Bao, M. Sustainable Careers of Teachers of Languages Other than English (LOTEs) for Sustainable Multilingualism in Chinese Universities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Song, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, Q.; Grimm, A. Building World Class Universities in China: Exploring Faculty’s Perceptions, Interpretations of and Struggles with Global Forces in Higher Education. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2018, 48, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickson, A. A Qualitative Case Study Exploring the Nature of New Managerialism in UK Higher Education and Its Impact on Individual Academics’ Experience of Doing Research. J. Res. Adm. 2014, 45, 47–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, M.; Mabe, M. The STM Report: An Overview of Scientific and Scholarly Journal Publishing; International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers: Hague, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y. A Diachronic research of the development of foreign linguistics in China. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Inter-Cultural Communication, Moscow, Russia, 8–9 December 2020; pp. 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; Cai, C.; Fan, Q. The Effects on National Foreign Language Capacity Produced by Funding Programs: A Comparative Analysis of the Chinese and American National Funding Programs Related to Foreign Language. Foreign Lang. World 2014, 160, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Wang, Y. Capital Advantages: Could Colleges and Universities Located in Beijing City Win More National Social Science Fund Projects? Appl. Econ. 2020, 52, 4135–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkman, B. Language Ideology or Language Practice? An Analysis of Language Policy Documents at Swedish Universities. Multilingua 2014, 33, 335–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M. Globalization of English Teaching and Overseas Koreans as Temporary Migrant Workers in Rural Korea. J. Socioling 2012, 16, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanvers, U. ‘If They Are Going to University, They Are Gonna Need a Language GCSE’: Co-Constructing the Social Divide in Language Learning in England. System 2018, 76, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, X.; Zheng, Y. Multilingualism and Higher Education in Greater China. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2019, 40, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, Y.; Gao, X.; Xia, J. Problematising Recent Developments in Non-English Foreign Language Education in Chinese Universities. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2019, 40, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, H. 2016 Annual Report on Foreign Language Education in China; Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, A.S.L. Language Education in China; Hong Kong University Press: Hong Kong, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, S. The Current Situation, Problems and Solutions of the Non-Universal Languages Majors Construction in China. Technol. Enhanc. Foreign Lang. Educ. 2017, 174, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G. Policy Situation, Organizational Action Logic and Individual Behavior Choice. J. High. Educ. 2019, 40, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. On Ways of Facilitating University Foreign Language Faculty Development. Foreign Lang. Learn. Theory Pract. 2017, 2, 1–4+15. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Zhou, Y. A Visual Analysis of the Trajectory of Female Expert FL Teachers’ Professional Development at Tertiary Level. Shandong Foreign Lang. Teach. 2022, 43, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Tao, J.; Gong, Y. A Sociocultural Inquiry on Teacher Agency and Professional Identity in Curriculum Reforms. Foreign Lang. Teach. 2018, 19, 28–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. The Professional Identity of Less-Commonly-Taught Foreign Language Teachers in a University from the New National Standard Perspective. Foreign Lang. China 2019, 16, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Q.; Zhang, H. Career Development of University Teachers of Less-Commonly-Taught Foreign Languages: Challenges and Dilemmas. Foreign Lang. China 2017, 14, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Guo, X. Publishing in and about English: Challenges and Opportunities of Chinese Multilingual Scholars’ Language Practices in Academic Publishing. Lang. Policy 2019, 18, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillis, T.; Curry, M.J. Academic Writing in a Global Context: The Politics and Practices of Publishing in English; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wen, Q. The Impact of a Professional Learning Community on the Development of University Teachers Instructing Different Foreign Languages. Foreign Lang. World 2020, 2, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, J.; Zhao, K.; Chen, X. The Motivation and Professional Self of Teachers Teaching Languages Other than English in a Chinese University. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2019, 40, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecology of the Family as a Context for Human Development: Research Perspectives. Dev. Psychol. 1986, 22, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–Resources theory. In Wellbeing: A Complete Reference Guide, Work and Wellbeing (Vol. 3); Chen, P.Y., Cooper, C., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2014; pp. 37–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.P.; Westman, M. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barkhuizen, G. A Narrative Approach to Exploring Context in Language Teaching. ELT J. 2007, 62, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Neveu, J.-P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the Role of Resources in Conservation of Resources Theory. J. Manage. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, J. A Survey of the Research Focuses and Trends in Foreign Language Studies in the 2006–2010 National Social Science Fund. Foreign Lang. Teach. Res. 2011, 43, 772–779+801. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Q.; Lin, L. An Interview Study of the Strategies and Attitudes of Blind Reviewers in Evaluating Applications for the National Social Science Fund of China. Foreign Lang. World 2017, 178, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. Exploring the Academic Output of Youth Teachers in Universities from the Perspective of New Managerialism. Beijing Educ. (Higher Educ.) 2020, 3, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Xing, J.; Zheng, S. Breaking the “Iron Rice Bowl”: Evaluating the Effect of the Tenure-Track System on Research Productivity in China. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3672830 (accessed on 15 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. Misuse and Correction of the Up-or-out Rule for Faculty of University. China High. Educ. Res. 2021, 12, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z. 300 Questions of Funding Application for Humanities and Social Sciences; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The Influence of Culture, Community, and the Nested-Self in the Stress Process: Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K. Academic Publishing: Issues and Challenges in the Production of Knowledge; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Xue, E. Creating World-Class Universities in China: Ideas, Policies, and Efforts; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, M.; Ma, J.; Teng, J. Portraits of Chinese Schools; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Hakanen, J.J.; Demerouti, E.; Xanthopoulou, D. Job Resources Boost Work Engagement, Particularly When Job Demands Are High. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duan, J.; Yang, J.; Zhu, Y. Conservation of Resources Theory: Content, Theoretical Comparisons and Prospects. Psychol. Res. 2020, 13, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Job Demands and Job Resources as Predictors of Teacher Motivation and Well-Being. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 21, 1251–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morrison, P.S.; Dobbie, G.; McDonald, F.J. Research Collaboration Among University Scientists. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2003, 22, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, J. Academic Publishing in English: Exploring Linguistic Privilege and Scholars’ Trajectories. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 2019, 18, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).