1. Introduction

Student mental health has gained significance on a global scale. Results from the recent WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student (WMH-ICS) Project showed that first-year college students from 19 colleges in eight different nations had a significant prevalence of mental health disorders. A lifetime mental disorder was present in 35% of respondents, whereas a 12-month condition was present in 31%. Two years prior, the WHO WMH Surveys indicated a lower prevalence (20.3%) [

1]. This was conducted in a wider range of nations, including those with low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Moreover, the mental health of university students in Southeast Asia showed that the median point prevalence for depression was 29.4%, for anxiety it was 42.4%, for stress it was 16.4%, and for disordered eating, it was 13.9%. A total of 7–8% of pupils reported having current suicide thoughts. The prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity was high. Despite the high frequency of mental health issues, there was a low willingness to seek professional assistance [

2]. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, disruption has been provoked in higher education institutions. For instance, adjusting learning patterns such as online learning, on the other hand, some challenges emerged: students having a challenging time as well as procrastination behavior, especially during the lockdown in the pandemic. These impact directly on academic performance, exacerbated by uncertainty and the stress showed negative impacts, both physical and emotional.

In developing nations such as Thailand, Musumari et al. [

3] analyzed the use of mental health services by Thai university students. Approximately 6% of students have previously used mental health services. To address these problems, many universities have begun carrying forward mental health policies and assigned this responsibility to the academic advisors and the Division of Student Affairs. Since the Thailand Qualifications Framework (TQF) mandates academic advisers to participate in offering counseling and guidance [

4], this specific obligation requires academic advisors to assist students under supervision by covering academic and mental health issues by providing counseling to their students. However, this responsibility of academic advisors in higher education differs from many western and some other countries that focus solely on academic issues. In contrast, personal and mental health issues are the responsibility of the psychology profession. As such, the referral has been made to the university counseling center instead. Furthermore, it turns out that many academic advisors are unprepared and lack the competency to care for mental health issues. Academic advisers with little or no competence would be unable to fully serve their students, obtain awareness, and effectively address their academic and psychological issues. Additionally, the referral procedure at a time of need could be delayed due to a lack of counseling skills, which could be contrary to students’ well-being or eventually end up dropout from school due to the problems [

5]. Reflecting on this point, students also reflected on the non-availability of easily accessible student-friendly services [

6]. Preventing is better than cure and prolonged stress can lead to serious health issues and severe mental illness [

7,

8]. Therefore, it is essential to develop academic advisors’ competency in caring and providing brief basic counseling to reduce stress and initially prevent severe mental illness responding to transforming the education system into the new normal. This will be helpful in early detecting, lending a hand to initial support, and making referrals to additional helping professions [

9] such as school counselors, counseling psychologists, or psychiatrists if necessary. Academic advisors’ counseling competence possesses a set of skills handy in conducting the counseling service, helpful for facilitating students to reach the self-development as optimally as possible and fostering effective counseling services. Hence, continuously further developing counseling competency should be conducted in the utmost school policy for a better quality of counseling service as soon as possible [

10].

Counseling competency refers to a counselor’s ability to ensure that clients receive effective and ethical services [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The concept of counseling competency is involved with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of those working in the helping profession, particularly counseling psychologists [

15,

16,

17]. There are many ways to enhance an academic advisor’s counseling competency. One of the effective ways is through a training program. Besides academic problems, some students have faced sensitive mental health issues in which brief initial psychological support would be helpful. Thus, implementing counseling theories in a training program has helped academic advisors gain competence in dealing with both general and sensitive issues. Brief interventions (BIs), frequently with a motivational interviewing approach [

18], have been demonstrated to be one of the most effective individual-centered strategies for substance use [

19]. Creating a brief training program using integrative group counseling techniques helps quicken the training, save costs, and foster a wide range of experiences during training. This way, it is beneficial for academic advisors, especially those who have packs of workload and lack of availability to allocate extensive time to attend training.

With limited research on the counseling competency of academic advisors in higher education, researchers intended to shed light on this area. In addition, the effort has been made to develop practical brief training appropriately for academic advisors in this context using a quasi-experimental research model to measure the effectiveness of the training program. The significance of the present study brings a clearer notion of the level of counseling competency of the academic advisors in higher education in Thailand. Furthermore, an innovative brief training program integrating group counseling was obtained. This innovation would be beneficial for the university administrators to consider further developing the counseling competency of academic advisors in higher education.

2. Literature Reviews

Counseling competency refers to a counselor’s ability to ensure that clients receive effective and ethical services [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Counseling competency addresses the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of the helping profession, especially counseling psychologists. Recent studies highlight that counselor awareness and problem-solving foster the effectiveness of group counseling [

15,

16,

17]. Hence, counseling competency is consistent with the context of academic advisors that require levels of basic counseling competency for assisting students not only on academic but relevant mental health issues [

20]. The more academic advisors possess high counseling competency, the more significant support they would provide to help their students reach their academic goals. However, academic advisors with low or little competence would not be able to fully satisfy their students, gain insight and deal well with their school and relevant problems. Also, due to the lack of counseling competency, the referral process in a time of need might be delayed and impact students’ well-being. Because of their lack of competency, counselors could lead a counseling service to engage in unethical behavior [

21]. If an ethical breach occurs, obligatory treatment, therapy, advising, or being prohibited from a profession [

22].

In the past, counseling literature has concentrated on different classification schemes used to evaluate counseling abilities. Finally, over the past 12 years, evaluations of counseling competency have included the measurement of verbal response modes, nonverbal behaviors, and counseling facilitation circumstances (e.g., Counseling Skills Scale [CSS]; [

23]; Skilled Counseling Scale [SCS]; [

24]. Lately, Lambie et al. [

25] evaluated counselors-in-training at multiple points during their practicum experience using the Counseling Competencies Scale (CCS;

N = 1070). A 2-factor model (61.5 percent of the variance explained) was constructed after the CCS evaluations were randomly divided for exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis: factor 1, counseling skills and therapeutic conditions, and factor 2, counseling dispositions and behavior. There are 11 items in the first CCS-R component; counseling skills, and therapeutic conditions focus on primary counseling competencies (verbal and nonverbal), as well as factors that support a therapeutic relationship with the client. The following 12 elements compose another factor, counseling dispositions and behaviors, which focuses on characteristics and practice in counselors-in-training that are essential for counseling competency. In this study, the conceptual framework of counseling competencies is based on dimension 1; counseling skills and therapeutic conditions, and dimension 2; counseling dispositions and behavior [

25]. However, in the modern era, providing psychological counseling needs an understanding of information such as rules, regulations, and policies in each environment. Furthermore, to understand ethical and legal practice as well as multiculturalism is also essential. Therefore, the main assumption for creating a test to be used in this research has been the framework of multicultural competency [

26]. In summary, three domains of counseling competency; Counseling skills, Attitude, and knowledge were conducted in this study.

The accurate, reliable, and timely assessment of learners is an essential domain of teaching & training during psychological professional courses. The Multiple-Choice Questions (MCQ) are tried-and-true techniques for quick evaluation of achievers. In their analysis of the validity of MCQ examinations, Gajjar et al. [

27] underlined that an effective MCQ accurately assesses the knowledge and may distinguish among students of various capacities. While Sharif et al. concluded that MCQ was an effective tool for assessing learners’ achievement [

28]. According to Bloom’s classification, MCQs should be created to evaluate learners’ cognitive, emotional, and psychomotor skills. Our study was designed to determine whether multiple-choice questions (MCQs) are useful in evaluating general anatomical knowledge, however, most of the questions are factual.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Sampling

The purpose of this study was to study counseling’s competency of academic advisors in higher education and develop counseling’s competency of academic advisors in higher education. This quasi-experimental study was part of the development counseling competency of academic advisors in higher education. This study was divided into two following stages:

Step 1: study the counseling competency of academic advisors in higher education

The sample size was calculated using the G*Power program to be 250 academic advisors. The research samples were selected using the criteria: (1) aged > 18 years old; academic advisors in higher education who have been working at Mahasarakham University, Thailand, from three main faculties group: humanity and social science, engineering and technology, and health science; (3) able to communicate in the Thai language, and (4) willing to participate. Participants who were unwilling to participate were excluded from this study. The sample of this study was randomly selected from the target population using a convenience sampling technique with proportional allocation. The sample of this study used CCAAHET for measuring the counseling competency of academic advisors in higher education.

Step 2: develop counseling competency of academic advisors in higher education. Two hypotheses were proposed.

Hypothesis 1. Counseling competence of the intervention group after participating in the BCCTP is higher than before the experiment.

Hypothesis 2. Counseling competence of the intervention group after participating in the BCCTP is higher than the control group.

A total of 60 samples were selected using the following criteria: participants with counseling competency scores rating “low to moderate” from step 1 and voluntarily participated in the training. Participants who could not attend full training were excluded from this study. The participants were equally divided into two groups (control and intervention groups). The match pair method used similar scores and characteristics to minimize extraneous variance. The intervention group received a brief counseling competency training program (BCCTP) while the control group was on their routine schedule. The intervention group and the control group used CCAAHET again for measuring the post-test of counseling competency of academic advisors in higher education after participating in the BCCTP.

3.2. Intervention

After the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, we met with participants and explained the study objective and procedures, including sample rights protection. Signed informed consent was obtained from all participants who were willing to participate. The program covers all three counseling elements: attitudes, knowledge, and counseling skills. The 3-day training program activities include lecturing, small group, whole class practice, case study, group activities, and discussion. It consists of 8 topics, the first 3 of which are focused on the development of attitudes, and topics 4–8 are skill developments. As for the development of knowledge, the researchers integrated their knowledge with practice.

In the intervention group, participants were randomly assigned and asked to attend the Brief Counseling Competency Training Program (BCCTP) for eight sessions (90 min each) and to join activities for three days. Session 1 consisted of relationship building, basic knowledge of the counseling process, roles of counselor and counselee, and positive attitudes building towards the teaching profession. Session 2 was to enhance learning and understanding and practice basic counseling techniques and skills. The participants were trained to be aware of and recognize emotions and feeling individuals express through their facial expressions and gestures. Session 3, the training program was designed to enhance the ability to communicate and respond to one’s and other emotions and feelings. Session 4 was designed to develop an emphatic understanding of people around as well as society. Session 5 was delivered by means of improving self-regulation ability in three dimensions: cognition, emotion, and behavior. Session 6 was designed to improve probing competency. Session 7 was set to enhance the ability for interpreting clients’ both verbal and nonverbal expressions. Session 8 was designed to enhance competency in interpreting the verbal and nonverbal language of the client and improve challenge skills and pattern of thought, emotion, and behavior appropriately. This is based on Bandura’s social learning theory and Gestalt counseling, Person-Centered group Problem-based learning. However, the control group was on their routine schedule as academic advisors in the university.

3.3. Research Instrument

3.3.1. Counseling Competency for Academic Advisors in Higher Education Test (CCAAHET)

In the present research, we created the CCAAHET developed by the researcher based on Sue &Sue [

26], Patterson [

29], and Okun & Kantrowitz [

30] using a test-blue print or table of specifications to ensure proper content coverage, which was assessed using 40 items and 4-multiple choices of response options, A, B, C and D that consist of attitudes, knowledge, and counseling skills. To illustrate the CCAAHET items, the examples are outlined in

Appendix A.

Each item is scored as binary with (1) for correct responses and (0) for incorrect responses. Each item has only one correct response. Total scores ranged from 0 to 40 points. Individuals scoring less than 23 were assigned “low,” 24 to 31—“moderate,” and more than 31—“high” counseling competencies. Attitudes of counseling competency scores ranged from 0 to 10 points. Individuals scoring less than 3 were assigned “low,” 4 to 7—“moderate,” and more than 7—“high”. Knowledge of counseling competencies and skills of counseling competencies scores ranged from 0 to 15 points. Individuals scoring less than 4 were assigned “low,” 5 to 10—“moderate,” and more than 10—“high”. The CCAAHET was face content-validated by three experts in counseling psychology and two experts in Educational Testing and Measurement. Content validity of the CCAAHET was determined using a table of specifications. The CCAAHET was qualified with item difficulty (p) from 0.32 to 0.63, discriminative index (r) from 0.34 to 0.67, and internal consistency reliability index of CCAAHET was a coefficient alpha score of 0.80 using Kuder-Richardson formula 20 (KR-20).

3.3.2. The Brief Counseling Competency Training Program (BCCTP)

The researchers designed a brief counseling competency training program to enhance academic advisors’ counseling competency in higher education based on the literature review and blending integrative group counseling [

31]. The program covers all three counseling elements: attitudes, knowledge, and skills. The 3- day training program activities include lecturing, small group, and whole class practice, case study, group activities, and discussion. The training program was Item-Objective Congruence (IOC), ranging from 0.66–1.00.

3.3.3. Sociodemographic Variables

Socioeconomic characteristics consisted of six items with multiple choices and open-ended questions. We developed this tool based on literature reviews, including gender, age, education level, academic advising experience, years of academic advising experience, and faculty they were in.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 21 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) for testing the assumptions, study variables, and outcomes. Characteristics of the participants and the Counseling Competency of Academic Advisors in Higher Education score were described using descriptive statistics, including frequency (percentage) or mean ± standard deviation. Repeated measure ANOVA analyses were performed to determine the associations between Counseling Competency of Academic Advisors in Higher Education at different times. The assumptions of ANOVA showed no violations of normality and homogeneity of variance. The main objective of our study is to explore whether the improvement of those outcomes before and after a brief counseling competency training program differed between intervention and control groups. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

As shown in

Table 1, the majority of the participants were female, 72% (

n = 180), the most significant percentage of participants were 20–40 years (72%), and the majority of participants had doctoral degrees (68%). All participants had experience providing counseling to their students as an academic advisor (100%), and the highest number of experiences were 0–5 years (91.6%). Most participants were from the Faculty of Sciences (16%).

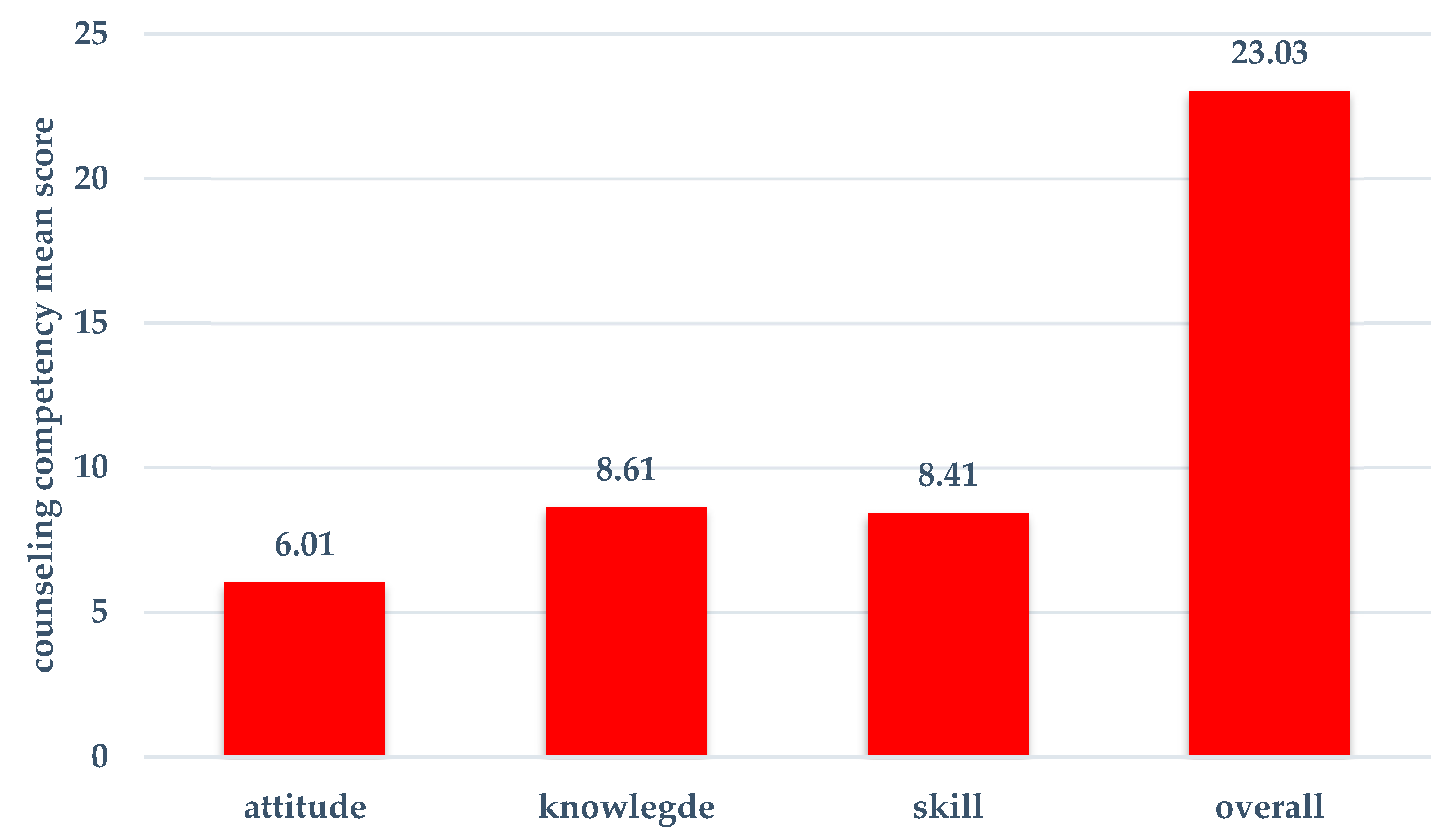

Based on

Figure 1, the overall counseling competency of academic advisors in higher education was at a moderate level (23.03 ± 6.11; Mean ± SD). Similarly, the participants showed moderate levels of each component of counseling competency: attitude of counseling (6.01 ± 1.82; Mean ± SD), knowledge of counseling (8.61 ± 2.21; Mean ± SD), and skill of counseling (8.41 ± 2.08; Mean ± SD).

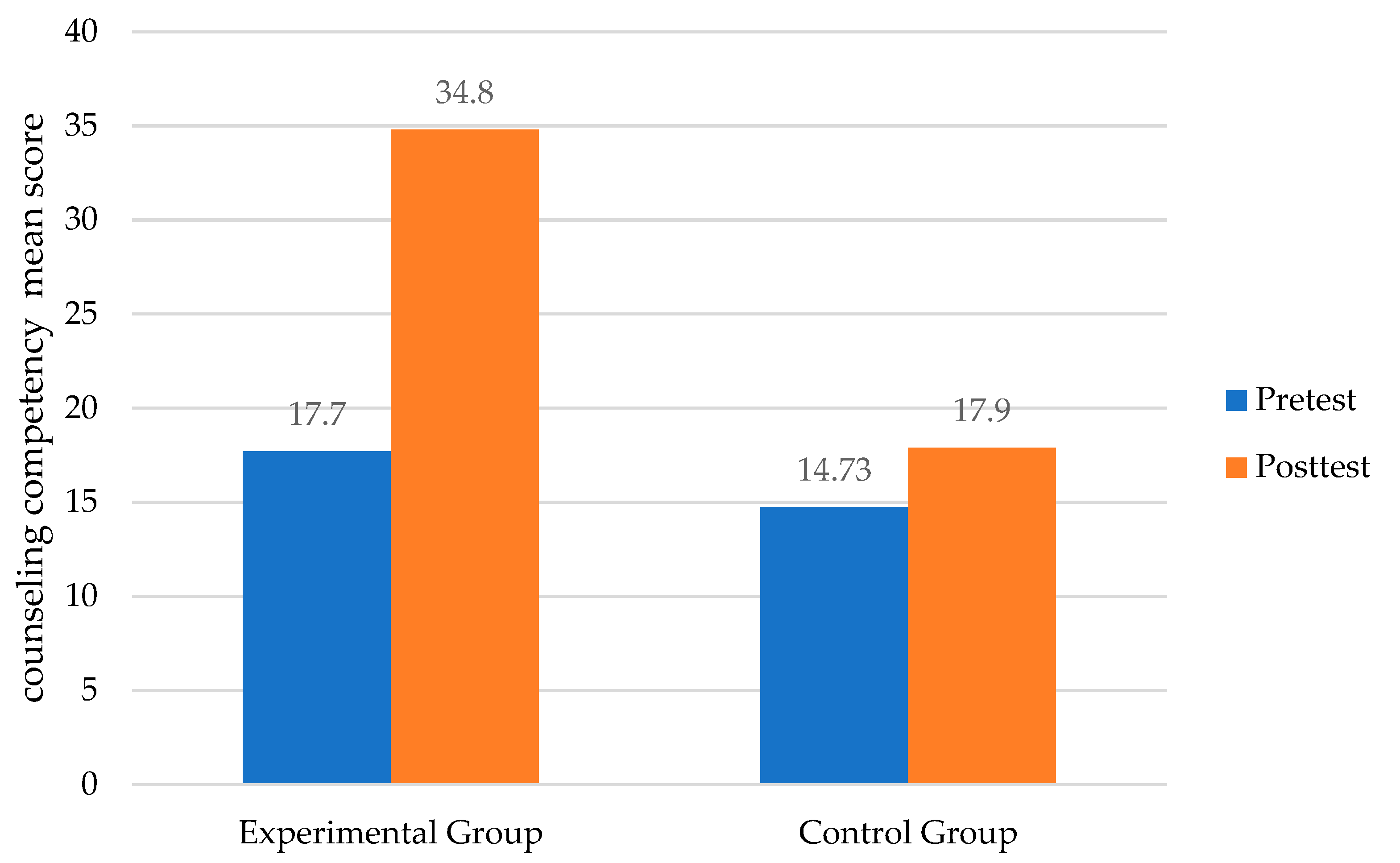

As shown in

Figure 2, the intervention group had a counseling competency pretest score at a low level (17.70 ± 1.49; Mean ± SD) and improved to a high level in the posttest (34.80 ± 1.77; Mean ± SD). At the same time, the control group had counseling competency scores at a low level on both pretests (14.73 ± 1.20; Mean ± SD) and post-test (17.90 ± 1.79; Mean ± SD).

As shown in

Table 2, academic advisors’ mean of counseling competency in higher education scores before and after BCCTP differed statistically significantly at 0.001. The interaction between the method and the experiment’s duration was statistically significant at 0.001. The mean counseling competency score between the intervention and control groups was statistically significant at 0.001.

5. Discussion

According to the standard of practice, the primary responsibilities of a faculty member in higher education in Thailand are instruction and research. Moreover, each faculty is assigned to be an academic advisor for students in the program. The role of an academic advisor, specifically in Thailand and some other countries, is to help the students under supervision learn about themselves, be aware of their capacities, deal with any challenges, and be mindful of available resources for better school adjustment and achievement [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. In this stance, academic advisors collaborate with their students to consolidate their educational, personal, and life goals, and their purpose in higher education experience [

38] Also, one-fifth of mental health issues started during university age could impact students’ general health, productivity, academic success, and social relationships [

6].

To teach at the university level, each faculty staff member must possess at least a master’s degree. Each faculty is an expert in his or her own field. However, except for the psychology department faculty staff, most academic advisors do not have a counseling psychology background. It would be challenging to provide counseling to students, especially on fundamental mental health issues relevant to their school. Therefore, it is essential to enhance attitudes, knowledge, and skills in counseling academic advisors to deliver this service more effectively. Specifically higher education in Thailand, most universities and colleges provide academic advising, and some student support services, but a few colleges also provide counseling and psychological services with trained psychologists or mental health professionals. Due to many of the universities’ lack of such specific mental health professionals, it is essential that academic advisors and relevant staff members promote positive mental health and establish collaborations with community mental health service providers to make appropriate referrals to ensure students’ health and mental health needs [

39]. There was little to know about the training program and support services for academic advisors in higher education in Thailand due to limited study has been published [

40]. However, it is important for student affairs professionals, staff, faculty (including the academic advisor) and administrators needed to obtain professional development and training in order to recognize mental health issues and gain knowledge of available resources to assist students [

41].

According to the present research hypothesis, a finding supported that counseling competence of the intervention group was improving after receiving the BCCTP. In comparison to the score before attending the program, each academic advisor was in the “low level.” However, after completing the program, their scores were developed to “a high level.” This result yielded that the training program, including counseling knowledge, practicing counseling skills, role plays, and case discussion, enhanced an academic advisor’s counseling competency in all dimensions (attitudes, knowledge, and skills). In agreement with this study, although this research aimed to improve the counseling competency of an academic advisor in higher education, the findings were consistent with several research conducted with teacher advisors in middle school and preservice teachers. This result was in line with a study on the competency enhancement of teacher advisors based on mindfulness and action learning principles. The teacher advisor improved their competence score after attending the program [

42,

43].

Following the research Hypothesis 2, the result of the competency training program was statistically significant. This finding indicated that the academic advisors who completed the BCCTP training program had improved competency scores compared to the control group. In developing the training program, review literature was conducted to explore and scope the design of the 3-day training program based on integrative group counseling [

31]. The theoretical principles and techniques employed to bolster competency stemmed from Microcounseling skills, Person-Centered Theory, Gestalt, Transactional Analysis, Social Learning Theory, Satir, and Brief Solution Focused Theory. These theoretical frameworks and techniques help develop empathy, awareness, the complementary transaction for effective communication (I, You message), and solution-focused approaches to yield directions for presenting issues. The training activities included lecturing background knowledge of basic counseling, microcounseling skills and integrative techniques demonstration and practice, dyadic and small group counseling role plays, and case discussion. The novelty of this research leads to policy guidelines and creating working flowcharts for an annual training modality to upskill/reskill academic advisors. In an academic context, the finding urged the development of a brief integrative training program beneficial for academic advisors who have time-consuming. It also strengthened theoretical practicing in the area of basic counseling in a more sophisticated way to help promote the academic advisors’ counseling competence in integrative brief training program.

COVID-19 pandemic impacts drastically on student mental health particularly stress and anxiety surrounding financial constraints, uncertainties regarding academic performance and career perspectives, life struggle, and isolation. Therefore, possible mental health support during this abruption could be ongoing research [

6]. According to roles, functions, and the importance of academic advising, it is fruitful for university administrators to situate academic advising alongside their learning and teaching mission [

44]. Also, academic advising can be a lifelong learning experience; academic advisors need the appropriate level of opportunity, support, and fulfillment to sustain their level of commitment [

45]. The future perspectives and sustainability of this research shed light on availability training programs for academic advisors to further provide counseling to their students on a deeper level. As mentioned in Hernandez’s [

40] research, this finding will be background support evidence to develop a further study to promote academic advisor’s important role and competency in helping their students’ achievement. It is essential to ensure that participants of the study are not harmed in any way [

46].

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

The academic advisors in higher education in Thailand play an essential role in helping students adjust well during university life to achieve their academic goals and experiences. Findings of this study indicated that after participating in the counseling training program—BCCTP, their competency had improved from a “low level” to a “high level.” and significantly differed from the control group. The results of the present study informed that the participants had improved their counseling competence highlighting basic counseling knowledge, counseling skills, and attitudes toward counseling and helping behavior. As BCCTP was designed by integrating microcounseling skills and several counseling theoretical principles and techniques from humanistic to postmodern, the intervention helped develop awareness, empathy, effective communication, and solution venues beneficial in a short period of time. It would be helpful for academic advisors to implement this competency to serve their students. This innovative intervention could be implemented for all new academic advisors or ones who have been in this service for a long time but need supplementary tools to better serve the students, especially in the psychological dimension. Therefore, in this context, university administrators should consider developing annual training plans for new academic advisors to attend. In addition, university policy and mission should be set to support the academic advisors to provide a good learning experience to the students for their school accomplishments as academic advisors play an essential role in helping students’ academic and personal success. The competency enhancement could be in regular annual training, reskill and upskill channels, and a counseling committee network to support, strengthen and sustain this role and responsibility.

Although BCCTP effectively enhances academic advisor counseling competency, some considerations for application should be addressed regarding a few limitations. To effectively deliver training to an academic advisor, the training provider must have background and experience in the group counseling approach. BCCTP model is rooted in universal counseling principles and framework. However, it needs to consider the uniqueness of the roles and functions of academic advisors in higher education in Thailand. Also, the root causes of students’ struggles and challenges are from general, personal, and culturally specific variables. Therefore, the implementation of this intervention should be mindedly applied in a multicultural trend and context.