Abstract

With the increasing number of smart devices and connections in Internet of Things (IoT) comes risks—specifically involving consumer data protection. In this respect, this exploratory research examines the current issues of IoT and personal data protection in Malaysia that includes: regulatory frameworks and data governance; issues and gaps; and key challenges in implementation. Results from this mixed-methods research indicates that a majority of consumers expressed concern about personal data risks due to increased usage of IoT devices. Moreover, there is a crucial need to increase regulation and accountability in the industry. In this regard, collaboration and partnerships between the main stakeholders are essential in tackling emerging issues of IoT and personal data protection. In order to strengthen IoT data governance, the fundamentals should be: strengthening consumer education and smart partnership between government-industry-civil society; providing motivation for active participation of NGOs and civil society; and obtaining industry buy-in. This paper also proposes a structure for the governance of evolving data-related technology, particularly in the case of data breaches or cyber incidents. It adds to the wider discussion of the current scenario, and proposes a model of collective responsibility in IoT data governance that is underpinned by the three principles of fair information practices, privacy impact assessment and privacy accountability.

1. Introduction

Internet of Things (IoT) denotes a universal network of machines and devices capable of interacting with each other via sensors without human input [1]—which is widely recognised as disruptive technology with incredible growth, impact and potential in serving business and community needs [2], as well as a proven strategy and innovative technology of firm development [3]. In this context, IoT explores new ways for users to interact in smart spaces through the development of smart objects and services, while data is gathered on queries predetermined by manufacturers. Making sense and use of these data streams will result in better and more customer-centric services [4]. Nevertheless, due to the nature of the technology used and the volume and type of data which will be transferred across the Internet, it may lead to incidents of misuse. This scenario poses its own set of challenges—specifically for the public, in terms of personal data protection.

This study is mainly motivated by the recent concerns on the increasing use of IoT related devices that potentially lead to the risks associated with personal data protection, as well as the lack of a comprehensive data protection framework and institutional settings for IoT data protection, particularly among the developing economies. There is rising concern about the lack of a mature and comprehensive framework for data governance of IoT related activities [5,6,7,8]. This concern is particularly crucial due to the increasing number of IoT devices connected to each other and the volume of personal and consumer data being transferred via the networks. It is vital that the security of these sensitive data be protected [9]. At the same time, a critical aspect that is often overlooked is data privacy [10]. The privacy requirements by developed nations, such as the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR), will cause increasing challenges for developing countries wishing to penetrate the global market (if they do not comply with such requirements). Security will also vary according to network conditions—hence the existing security framework (which may be country specific) will not be able to keep IoT data secured for all the devices which are connected to the network [11]. Thus, this raises concerns on the role of government and agencies in IoT and personal data protection in the national context.

In 2012, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) introduced the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration, in which Article 21 calls for the right of every person to be free from arbitrary interference with his or her privacy, family, home, or correspondence including personal data, or any attacks upon that person’s honour and reputation [12]. This led to the ASEAN Framework on Personal Data Protection in 2016 which aims to provide guidance for the implementation of data protection laws and regulations within the region. As of April 2021, three countries in the Southeast Asian region have data protection laws, namely: Malaysia’s Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) (2010); the Philippines’ Data Privacy Act (2012); and Singapore’s Personal Data Protection Act (2012). In Malaysia, the PDPA, which has been in place for several years now, is limited to commercial transactions. As seen over the last few years, there have been several high-profile data breaches involving the public sector data [13]. Hence, an in-depth look into the effectiveness of such regulations at tackling the challenges of new technology such as IoT—as well as institutional changes required for the effective adaptation of IoT data protection regulations or models—will certainly be important. The concerns about IoT adoption and associated data security and privacy risks should be taken seriously [14,15].

It is based on the viewpoint that the convergence of IoT and other Industry 4.0 technologies toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) platform is possible, but this demands supportive innovation and policies [16] and, in the case study of Malaysia, this mixed methods paper aims to determine the issues of IoT consumer data governance and propose measures to strengthen consumer data protection. Ultimately, this paper attempts to address the following two questions: (a) “What are the emerging scenarios of IoT consumer data security issues?” and (b) “What institutional changes and strategies are required to achieve a better framework for IoT data governance?” The main contribution of this paper is twofold. First, it determines a multi-stakeholder model for the governance of IoT consumer data in response to data security issues we observed, highlighting the crucial need of collaborative governance framework for IoT data protection. Second, based on the model established, this paper suggests the mitigating approaches in addressing IoT related data security issues. Echoing this, the multi-stakeholder approach for climate change governance specifically the system for information sharing [17] allows for a collaborative and inclusive governance of emerging issues. Recognising the economic, social, and environmental potential benefits of IoT whilst addressing emerging issues may lead to better adoption and usage of this technology.

Realising the rapid changes and developments in IoT and other emerging technologies, this paper provides a flexible and dynamic approach to tackling emerging issues whilst recognising that consumer awareness of IoT privacy and security is crucial to the success of IoT adoption [18,19], whereby concerns of security and privacy can affect consumers’ buying, trust, and confidence on consumer IoT devices [20]. Nevertheless, it can be noted that the consumers in developing countries may be less aware of their rights and risks [21]. The traditional mitigation techniques may not be adequate for addressing these threats; therefore, there is a need for further research in block chain technology [22], and a multi-stakeholder channel for cooperation and feedback will be very useful in this aspect.

However, it would be challenging and premature to institute policy development when agreement and rules for IoT data governance are not fully comprehended [8]. As a whole, this study develops a collaborative governance framework for IoT data protection and support evidence-based practice (and governance). It is both intellectually rich and practically important as it supplements fragmented literature by highlighting issues on IoT privacy and security, as well as consumer awareness and trust based on the case study of a developing country, Malaysia. This paper consists of eight sections. After this introduction, Section 2 provides the conceptual basis of IoT data protection and the establishment of a conceptual framework. Section 3 provides a brief overview on IoT development and framework for data governance. Section 4 elaborates the research methods for data collection. Section 5 presents the data and analysis derived from the case study. Section 6 provides the discussions and implications of the main findings; whereas Section 7 explains the limitations and ethics concerns of the study. Finally, future research and conclusions are presented in Section 8.

2. Literature Review

2.1. IoT Data Protection and Security

The key differentiating factor of IoT is the potential of the data generated from things rather than people [23], with the main value of delivering customer-centric and enhanced services to users. However, the main concern regards the debate over whether the consumer data is captured anonymously and presented in an aggregated form. For instance, Williams, McMahon [24] examined the vulnerabilities in everyday consumer devices, such as TVs, webcams, and thermostats, which have been equipped with Internet connectivity in order to increase functionality. As IoT systems deal with a huge amount of data, there is a need to develop all-inclusive security protocols which will be able to manage these data streams to provide a secure environment for the whole IoT system [25]. Nonetheless, as the capacity for complex computing is limited with most consumer devices (as compared to a computer or cell phone), there is the potential for “man-in-the-middle” attacks [4].

IoT connections come in various forms or technologies in order to deliver real-time messages via a common platform through wired networks, wireless networks, or cloud computing methods that understand and provide warnings—communicating and monitoring business operations [26]. These platforms/technologies include proximity-based connections (e.g., radio-frequency identification (GPS), Bluetooth, and Wi-Fi), global positioning systems (GPS), 4G/5G, or hard-wired systems. Common use of IoT systems—which involves the integration of devices such as tags, sensors, smartphones and wearable devices with the Internet—anticipates new problems and attacks [27,28]. Such extensive technological development in IoT raises different needs from a data protection framework compared to the traditional Internet. These include: authentication and data security [29]; lack of capacity for complex computing which may allow data to be intercepted; and data integrity, which is the assurance that data will not be modified while being transmitted [4]. Therefore, it is important that only users who are authorised and authenticated be allowed access. This requires authentication schemes which include elliptic curve cryptography, self-certified keys cryptosystems, and hash functions [30].

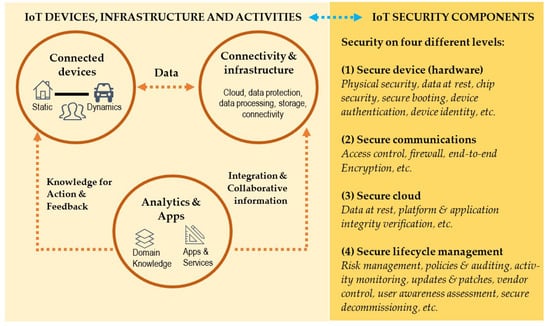

Figure 1 illustrates an application scenario for IoT data secured ecosystem. In general, there are three building blocks that construct the basic applications (and functions) of IoT. These include: (a) connected devices—both static devices (e.g., house appliances) and dynamic devices (e.g., vehicles); (b) connectivity platforms and infrastructure (e.g., cloud, data protection, data processing, storage, and connectivity); and (c) analytics and apps (e.g., domain knowledge generate from the used of IoT, and apps and services). The outputs from the interactive used of these three blocks can be in a form of data, integration and collaborative information, and knowledge for action and feedback. Together with the devices, infrastructure, and analytics, these outputs need to be securely protected. The security protection can be introduced and applied on four levels, namely, the devices (hardware), channels and methods of communication, cloud and storage platform, and lifecycle management which associated with the perspectives of risk management, policies and auditing, awareness assessment, etc.

Figure 1.

Scenario for IoT data secured ecosystem. Source: Adapted from Malaysia National Internet of Things (IoT) Strategic Roadmap; and IoT Analytics (https://iot-analytics.com/5-things-to-know-about-iot-security/ (accessed on 1 August 2022)).

The use of IoT applications inevitably impacts user privacy which relates to data collection and its use—including authorised services by authorised providers—particularly informed consent which is prior to data collection by any party, including IoT manufacturers or any stakeholders within the IoT ecosystem [4,31]. However, in order to obtain informed consent, the data subject must clearly understand how their data will be utilised within the system. This can be challenging as the world is flooded by a deluge of sensor data—those handling sensor data may not be trained or aware of the proper ways of handling data, in particular sensitive personal data [32]. In this respect, it is crucial that organisations handling such data be required to develop a data management plan throughout the lifecycle of the data. Cavoukian [33] introduces the concept of privacy-by-design which is implemented in the EU’s Global Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The concept operates on putting responsibility on the industry to provide privacy to the consumer by incorporating it into the product design. The spill-over effect that the GDPR will have on global data protection laws and standards [34]—as well as how privacy is viewed and safeguarded as a fundamental human right [35]—will be seen in market and business strategies where privacy-by-design may be widely applied. Therefore, should any developing country (including Malaysia) wish to strengthen trade and economic cooperation with EU countries, it is vital that the basic principles of data protection be translated into local settings.

2.2. Principles of IoT Data Governence

Although the concept of IoT data governance is still vague and not fully defined, most analyses on IoT governance pinpointed the main issues of legitimacy, transparency and accountability [8]. Undeniably, data governance (together with data security) is considered a key element to ensure IoT remains secure, private and of an acceptable standard—this involves decision rights, roles, and accountability [8,36,37]. At the operational level, data governance focuses on assigning decision-related rights and duties in order to be able to adequately handle data [38]—this includes ownership and accountability in capturing, processing, and accessing data under defined conditions and sensitive circumstances [36]. It defines standards and procedures to ensure the proactive and effective handling and guidance of data management practices [37].

At the macro-level, the “thin” legitimacy and lack of transparency or accountability in IoT ecosystems remains a key challenge, and the concept of “multi-stakeholder in governance” is the way forward in governing digital data [39]. This concept of sharing power will pose some issues related to authority and security of information. However, a multi-stakeholder approach presents a unique opportunity for more efficient governance. Such an approach requires efforts to collaborate with external parties such as government and non-governmental organisations—including businesses, civil society, or even individuals [40]—and communication which helps establish trust between various stakeholders in scientific advancement activities [41]. Furthermore, in highlighting the conflict between individuals’ right to privacy versus national security in the governance of the cyber world, there is a need for a policy framework that will give weightage to both governance and the right to privacy [42].

These points on data governance and provision of data protection are important where the balance of power between citizens and government is fragile, and citizens are becoming increasingly aware of their rights and their power to influence change. Varney [43] states that whether or not the data are used by public bodies or organisations in the private sector, it is important that the public has confidence in the processing systems—as this will affect their willingness to provide consent for other innovative uses for the data.

In this respect, social governance is widely accepted as an emerging approach for IoT data governance. The aim of this approach is to create an agile (with free flow of information among the different stakeholders) but stable governance (with a collaboratively formulated regime) that is context and time sensitive; as well as a methodical governance mechanism to regulate activities in networked societies [44]. Such an approach operates on the principle of comprehensive control mechanisms of privacy, security, ethics, and competition to enforce the rights of citizens and consumers while protecting their data. The critical role of implementing governance in the IoT is to consider the completeness of control mechanisms—such as establishing the principles of privacy, security, ethics, and competition to enforce the rights of citizens and consumers and protect their data within an ecosystem. It is characterised by the following risk factors: environment; process; decision-making; operation; authorisation; data processing and information technology; moral; and financial [26].

In the realisation of social governance that adheres to these various complex risk factors, it is suggested that multi-stakeholders with variable-geometry mechanisms (which combine various top-down and bottom-up actions—depending on the technical environment and the given societal situation) should be preferred. Notably, this variable-geometry mechanism operates on the basis of enhanced cooperation of market participants and consumers in IoT data governance [45]. To conclude, the recent development of IoT data governance is about a function of scale in the context of data privacy. It is not static—on many occasions, we witnessed the privacy and data protection regulatory framework reinvent itself each time there were major changes and challenges [46]. Thus, this requires a social governance approach that demands multi-stakeholders with variable-geometry settings. This unique approach will be more explicitly explained in the collaborative governance framework in the following section.

2.3. Collaborative Governence Framework for IoT Data

Collaborative governance is defined as “the processes and structures of public policy decision making and management that engage people constructively across the boundaries of public agencies, levels of government, and/or the public, private and civic spheres in order to carry out a public purpose that could not otherwise be accomplished [47]”. This integrative concept arises from the growth of knowledge and institutional capacity, in which knowledge becomes gradually specialised and circulated among public and non-state stakeholders. This leads to a productive and effective collective decision-making process—one that is formal, consensus-oriented, and deliberative—which aims to make or implement public policy or manage public programs or assets [48]. The adaptation of a collaborative governance approach contributes to shaping and employing major policy drives in localities, attributable to inclusion of stakeholders in the decision-making processes [49].

Collaborative governance is seen as a response to the need for a more comprehensive government structure, as well as the need for individuals representing their respective stakeholder(s) to be broad-minded in considering the effect on others of setting up a collaborative initiative [49]. This fosters government accountability, greater civic engagement, consistent downstream implementation, and (most importantly) higher levels of process and program success—which leads to a reinforcing cycle of trust, commitment, understanding, communication, and outcomes that mark successful collaboration [50]. Indeed, a virtuous cycle of collaboration occurs when stakeholders’ collaborative forums focus on ‘‘small wins’’ that deepen trust, commitment and shared understanding. Such public agencies/institutions-initiated forums—which include non-state actors—provide direct engagement in iterative and collective decision making by consensus [48].

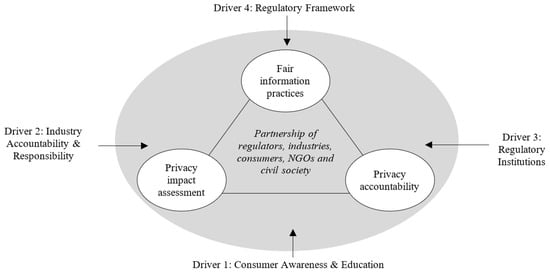

In the context of IoT, the approach of collaborative governance ought to consider the three principles of fair information practices, privacy impact assessment, and privacy accountability as underpinned in EU GDPR which came into effect on 25 May 2018. In GDPR, the individual’s control over their personal data is safeguarded via the key principles of: lawfulness, fairness and transparency; purpose limitation; data minimisation; accuracy; storage limitation; integrity and confidentiality (security); and accountability [51]. Thus, GDPR compliance requires a holistic people, process, and systems perspective [52]. This regulation lays down rules pertaining to the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data, and rules relating to the free movement of personal data [53]. While the GDPR only protects EU citizens, its influence is bound to be global and affecting all regions (including Malaysia) that target the European market and hold personally identifiable information on EU residents [54].

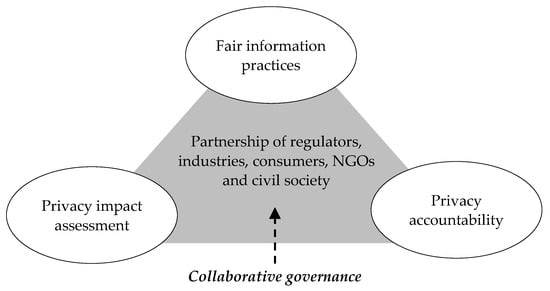

Drawing upon the principles of collaborative governance and EU GDPR, Figure 2 presents the conceptual framework for this paper. The framework shows how the three essential components of data protection—which are (i) fair information practices, (ii) privacy impact assessment, and (iii) privacy accountability—may be harnessed through a partnership of regulators, industry, consumers, and civil society towards collaborative governance for IoT data protection. This model highlights the larger effect collaborative governance will have on the overall ecosystem encompassing the main stakeholders.

Figure 2.

Collaborative governance framework for IoT data.

3. Malaysia’s Progress in IoT: Data Security and Governance

There has been an increasing number of cases related to security and privacy. The Malaysia Computer Emergency Response Team (MyCERT) reports that cyber incidents from 2010 till 2020 seem to be on the rise. Fraud and intrusion cases show an increase whereby in 2010, a total of 2212 cases of fraud were detected. This is in contrast to 3821 cases in 2017 and 7593 cases in 2020. As for cases of intrusion, a total of 2160 cases were reported in 2010 compared to 2011 cases in 2017 and 1444 in 2020. Data breach incidents have also been on the rise, which has increased public concern and awareness about security and privacy issues. These include: the largest data breach involving 46 million mobile phone subscribers [55]; the Malindo Data Breach [56]; and, more recently, the Malaysian Airlines frequent flyer programme, i.e., Enrich [57]. In Malaysia, statistics show that there have been 1.51 billion breaches of IoT devices in the first half of 2021, compared to 639 million the previous year [58]. Moreover, it was reported that the Royal Malaysia Police had to deal with almost RM400 million losses due to the cybercrime cases in 2018. This amount had increased to RM500 million in 2019 [59].

These cases highlight the vulnerabilities in online data and databases, as well as the risks of data storage including cloud and overseas storage. This is despite the Malaysian government’s serious efforts to establish its IoT ecosystem, including cyber security programmes and regulations. It is important to note that whilst there have not been IoT specific data breaches reported in Malaysia, globally there has been a worrying increase in cyberattacks on IoT devices in the last few years. In fact, discussions on IoT governance and the general Internet shouldn’t be separated or isolated—especially in problems related to security, interoperability standards and protocols [46].

Institutionally, the main regulators of IoT and personal data protection in Malaysia are the Department of Personal Data Protection Malaysia (JPDP), the National Cyber Security Agency (NACSA), CyberSecurity Malaysia (CSM), and the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC). Currently, NACSA is the organisation with the highest authority—as it is placed under the Prime Minister’s Department. There is no legal instrument that governs its activities, nor an authority body to coordinate efforts among stakeholders.

Policy-wise, Malaysia was among the earliest to undertake and design a national cyber security policy as well as enact cyberlaws in Southeast Asia. The Malaysian National Cyber Security Policy (NCSP) was launched in 2006 in order to address emerging and sophisticated cyber threats. The NCSP aims to improve trust and cooperation in the Critical National Information Infrastructure (CNII) both at home and abroad, for the benefit of the people of Malaysia (NCSP, 2006: 8). At present, the custodian of the NCSP is CyberSecurity Malaysia, which is under the purview of the Ministry of Communications and Multimedia Malaysia (KKMM). Meanwhile, the National IoT Strategic Roadmap which was launched in 2016 attempts to regulate IoT through the establishment of a council, as outlined in the National Roadmap for IoT in Malaysia [60]. While the roadmap acknowledges the issues of security and privacy in IoT, it does not incorporate a key component—namely, the policy and regulatory framework. The roadmap serves the purpose of stimulating IoT growth and does not cater for increasing security and privacy risks. As for personal data, there is a clear regulatory mechanism in PDPA 2010—approved by parliament on 5 April 2020 and in force since then. However, the current PDPA legislation is being reviewed in order to address the new challenges of IoT and Industry 4.0 (among other things). Table 1 shows the status of data security and governance in Malaysia.

Table 1.

IoT and personal data regulation in Malaysia.

Table 2 compares the current status and progress of PDPA among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states. Except Myanmar, Cambodia, Brunei, and Lao PDR, the other states in ASEAN have shown significant efforts to develop comprehensive data protection law. The Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand are the four states that have enacted PDPA during the period of 2010–2012. PDPA in the Philippines and Thailand covers both the public and private sector, whereas PDPA in Singapore and Malaysia is only for data collection and data use in private sector. It is interesting to note that for countries with PDPA, it is only Malaysia that does not require notification to the data owner in the event of a data breach [61]. Meanwhile, only the Philippines has established a specific independent data protection authority, that is National Privacy Commission (NPC), while Singapore and Malaysia have data protection agencies housed under a government agency. In the case of Vietnam and Indonesia, although there is still absent of single comprehensive PDPA, there are several serious efforts in initiating and improving the data governance of the state.

Table 2.

Data governance and personal data protection regulation in ASEAN member states.

4. Methods

This study employed mixed methods. First, a survey was conducted with the purpose of identifying issues and public perception on personal data protection in Malaysia. It is important to note that the purpose of the survey is to gauge some background views and public perception on the research topic before the in-depth interviews. It is not aimed at a full scale and extensive investigation on the significant correlations of the various determinants of the survey. In the second part of the study, in-person interviews were performed with the stakeholders to delve further into the issues identified in the survey and suggestions for a better IoT data governance framework.

4.1. Exploratory View on IoT and Personal Data Protection in Malaysia

The purpose of this survey is to provide some background on the general sentiment on IoT and personal data protection in Malaysia, as well as to assess the risks and value of further exploring this topic. It applies a purposive sampling on respondents whereby the main criteria were that the person must have experience in using IoT devices (e.g., smart TV, smart phone, or smart watch), is involved in the development of IoT applications (e.g., Fitbit, FavorIoT, or Smart Lock-up), and has good exposure or knowledge on IoT-related issues. As highlighted by Taherdoost [62], there is a need for establishing a sampling technique (such as purposive) prior to collecting data. This is due to the realistic assessment that it would be a never-ending process should the researcher aim to collect all relevant data in order to answer the research questions. The qualitative survey was distributed online among respondents for a period of three weeks in December 2018. Since the sampling was purposive, the respondents were able to provide useful and meaningful insights into the survey topics.

The survey consists of four main parts (i.e., respondent’s profile, IoT and personal data security, privacy by design model, and consumer data governance) with a total of 26 questions. The survey was developed following the guidance of several sources. In that respect, this study referred to reviews by Sivakumar, Jusman [63] on the various industries in Malaysia which are suitable for IoT applications. The EU GDPR was also referred to in developing the survey. Examples of key questions used in the survey are shown in Appendix A.

A preliminary study for a pilot test involving 10 respondents was conducted. The test was important for ensuring that the survey would garner the desired responses. The respondents were targeted through: social media (Facebook groups such as, IoT Malaysia, IoT Asia, Internet of Things, Malaysia Doctorate Support Group, and FavorIoT); professional associations (OWASP Malaysia Local Chapter, Malaysia IoT Association, Department of Personal Data Protection Malaysia, and Winners Innovative and Empowerment Network); and networking at seminars and conferences related to IoT (i.e., An Insight on IoT: Great Powers Come Great Challenges Seminar; Georgia and E-governance: The Journey in the Digital Age; Disruptive Technology Transformation: 4th Industrial Revolution—Opportunities and Challenges). The final number of respondents was 255, whereby 69% were female and 31% male. A majority of the respondents (98%) were between the ages of 21 to 50 years old. Of this number, 114 (44.7%) are from regulators, whereas 141 (55.3%) of the respondents are IoT users. Almost all respondents (98%) have a tertiary education background: Diploma (7.1%); First Degree (43.9%); Master’s degree (43.1%); and PhD (3.9%). In terms of monthly income, a majority of the respondents had an income of RM 2000 and above (86.2%), whereas 62.7% of respondents were of the income bracket between RM 5000 and RM 10,000. In short, the respondents can be generally classified as a group of educated and middle-income individuals residing in Malaysia who have experience in using IoT related devices and services.

4.2. Expert Interviews

Semi-structured in-person expert interviews were a crucial part of the research and aimed to answer the second research question on: the roles of government and agencies in consumer IoT and personal data protection; the feasibility of the privacy by design model to be incorporated in the Malaysian IoT environment; and the institutional changes required for this adaptation. The scope of the interview was based on the following themes as indicated in Table 3. A total of 11 experts were identified and interviewed. Experts were identified based on the definition given by Meuser and Nagel [64], which is that they possess specific knowledge on the topic. This included IoT, personal data protection, and consumer affairs in Malaysia or within the Asian region. The interviews were face to face and lasted between 2–3 h. The selection criteria for interview respondents are as follows: (a) holding a senior position in an organisation involved in cybersecurity, personal data protection, IoT application development/research or consumer awareness groups; and (b) within Malaysia or the Asian region. Table 4 shows the profile of the interviewees.

Table 3.

Scope of expert interviews.

Table 4.

Profiles of interviewees.

Throughout the interview process, interview confidentiality and anonymity were preserved through the use of pseudonyms. The interview recordings were transcribed manually to ensure that the information was interpreted correctly—including nuances and subtle meanings—and to avoid missing important nuggets of information and details which enhance the research [65]. The transcripts were then read through several times and compared with the recording, in order to form common coding maps and themes from the data. This allowed for better control over the data and data analysis process [66].

5. Data and Analysis

5.1. Scenario Setting and Perceptions on Consumer Data Governance

A total of 67.8% responded affirmatively that they are aware of recent data breach incidents in Malaysia (e.g., the cases of Uber and Telco), whereas 21.6% percent responded “No” and 10.6% were “Not Sure”. With regard to their awareness on the existence of the PDPA, a total of 78% responded affirmatively, whereas 14.1% and 7.8% replied “No” and “Not Sure” respectively. Subsequently, a majority of respondents expressed concern about personal data risks due to increased usage of IoT devices. Based on the keywords obtained from the open-ended questions, the respondents’ expressions can be categorised as: negative emotions; apathy; and positive emotions (Table 5). This categorisation is guided by work from Robinson [67], which categorises emotions into three categories: kind of emotion; positive emotion; and negative emotion.

Table 5.

Respondents’ expressions towards the risks of their personal data.

The survey also seeks to understand the different roles of IoT device manufacturers and regulators (Table 6). The results show that the respondents are still upholding a conventional view in which the manufacturers are expected to produce IoT devices with built-in data security features (43.1%); whereas the regulators are expected to perform in developing and implementing policies and standards (43.9%). A more significant role for the collaborative approach in data governing (as represented by ‘coordination with stakeholders’) is not ranked among the top priorities by the respondents. It is possible that since data governance is a new concept in Malaysia, the respondents have the view that the principal role should be held by the government instead of coordination with stakeholders. This finding will be explored further in the expert interviews.

Table 6.

Roles of IoT device manufacturers and regulators in providing adequate data protection for the consumer.

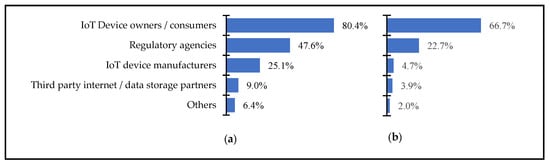

Respondents were requested to choose two parties who have the most authority to collect, share and use data (Figure 3). A significant majority of respondents (80.4%) felt that IoT device owners/consumers should have the most authority to collect, share and use data. This is followed by regulatory agencies (47.6%). Notably, device manufacturers (21.5%) and third-party Internet and storage partners (9%) have a low preference among the respondents. The question then arises about which party will provide this authority or whether it needs to be stipulated under legislation. In respect to who they thought had the most right to own the data collected by IoT devices, the majority (66.7%) chose IoT device owners/consumers. This is followed by regulatory agencies (22.7%), IoT device manufacturers (4.7%) and third-party Internet and data storage partners (3.9%). Ownership in this case is tied closely with the requirement that parties which want to utilise or access the data must first request and obtain informed consent.

Figure 3.

Stakeholders with the most authority in dealing with IoT data. (a) Collect, Share and Use Data. (b) Own Collected Data. Source: Authors’ survey (sample size = 255).

It is also important to examine the respondents’ level of trust in the key stakeholders of the Malaysian personal data protection ecosystem [41]. As shown in Table 7, the organisations deemed most trustworthy were the national government and regulatory agencies (78.4%). This was followed by intermediaries and government linked companies (65.9%). The least trustworthy were media including social media (52.9%) and political parties (55.3%). Industry fell into the neutral category with IoT manufacturing companies (44.3%) and third-party Internet providers (34.1%). Consumer associations also were categorised as trustworthy (37.8%) or neutral (37%).

Table 7.

Level of trust from stakeholders.

5.2. Qualitative Insights into Secured Data in IoT Ecosystem

5.2.1. Cybersecurity Readiness Issues

The expert interviews highlighted the importance of information sharing and cooperation between various stakeholders as a critical factor to ensure a safe and secure IoT environment. However, several main constraints have been quoted:

- Absence of a well-coordinated institutional setting and regulatory framework for handling issues related to cybersecurity—legal instruments and regulatory (governance) agencies seem scattered;

- Due to the rapid pace of technological change together with the lack of resources and talent faced by regulatory agencies, said agencies need to focus on talent management and alternative measures in order to keep up with the new technological advancements;

- The lack of priority placed on security, especially when it comes to budget and resource allocation. This is related to the importance of leadership in setting organisational security as a priority, in which resources are found to be channelled towards the operational and infrastructure needs of companies rather than to security. Moreover, there is a lack of enforcement within the current legislation and a lack of reporting on actions taken by enforcement agencies. This gives rise to the assumption that enforcement agencies are not playing an adequate enough role. This shortfall in handling data breaches is also observed in the industry (or service providers). This relates back to the obligation of data users to report any breaches to the authorities. Appendix B presents the main themes of cybersecurity readiness issues.

5.2.2. Data Governance Fundamentals

It is crucial to determine the main elements (and drivers) that serve as the foundation to design, deploy and sustain effective data governance. The interviewees were instrumental in sharing their expert views on these data governance fundamentals:

- The role of regulators and industry in tackling data security issues requires consumer education and empowerment. Since the global challenges of late (e.g., falling oil prices and COVID-19), it is worrying that security and personal data protection might be a lesser priority which may be reflected in national budgets. Therefore, smart partnerships between government, industry, NGOs, and civil society may provide a win–win situation for the relevant stakeholders;

- Therefore, the active participation of NGOs and civil society is required to establish these smart partnerships. In fact, civil society and NGOs play crucial roles in monitoring data and privacy protection. When conducting outreach, there needs to be clear demarcation of which sectors are championed by which organisation. Not only will the message be clearer and better received, but the reduction of redundant activities will allow for wider and more effective outreach activities;

- ‘Buy-in’ from the stakeholders is key to successful roll-out of policy measures. In the case of industry, personal data protection needs to be seen as a priority which could disrupt business continuity. It is suggested that awareness programmes are stepped up and the number of touch points with consumers and businesses are increased, as this will in turn increase the overall acceptance rate. Adequate time will be necessary for the mindset changes required. It was highlighted that in the past, regulatory changes had been introduced within a short span of time for implementation—which caused difficulties for businesses to adjust. Industry should also be made aware of incorporating privacy values into their business practices. They should also be required to share some responsibility and accountability in creating awareness. Appendix C summaries the main themes of data governance fundamentals.

5.2.3. Enhancing Regulatory Frameworks

With respect to efforts to enhance the regulatory frameworks, the interviews provided the following insights:

- Government is still expected to drive the agenda on regulatory framework, and the appropriate stage and types of measures for government interventions need to be determined. There is a norm whereby developing countries will face challenges when global monopolies are involved (which promote their own interests and have very little incentive to protect global consumers). Existing regulations need updating in order to address the new threats. As the existing PDPA does not apply to data that are processed overseas or handled by a third-party data processor, the onus is on the data user to ensure that adequate security measures are taken and overseen. Additionally, the use of non-legislative measures (such as standard code of practice) to promote awareness and shared responsibility among industry players needs to be considered. This is important especially when dealing with third-party service providers such as cloud storage or Internet service providers;

- When asked about the accountability of third-party vendors (which is not addressed in the current legislation), consumer interviewees were unconvinced that the present regulations are able to fully cater for the new technological advancements in IoT. The rapid advancement of technology poses a threat, whereby some of the clauses (or words) within the context of the act may be outdated. The role of third parties in this context is not really key, as the business (or the devices manufacturer) should hold the main responsibility for data protection;

- It is a key role of regulatory bodies to ensure that the IoT products imported into Malaysia conform to Malaysian and International standards. This includes certification of IoT devices. Appendix D presents the summary of respondents’ concerns on regulatory frameworks.

5.2.4. Summary of Findings

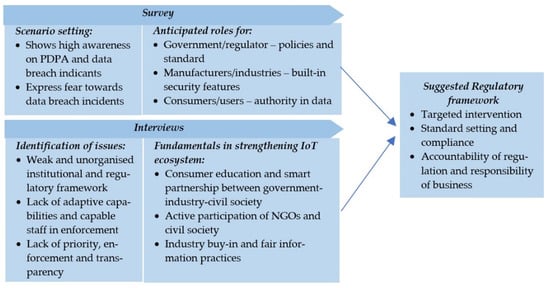

The current scenario of IoT data governance in Malaysia, which is derived from both the survey and expert interviews, is illustrated in Figure 4. The scenario indicated from the survey captures the perceptions and feelings of users of IoT related devices and services towards IoT data governance. Insights from a group of educated and middle-income Malaysian working adults who have experience in using IoT related devices and services affirmed that they are aware of the existence of data breach incidents in Malaysia. They expressed their fear (in a negative viewpoint) and concern over the issues of data security. Notably, their thoughts on the roles of government and manufacturers (or industries) are still conventional, i.e., government and regulators are to take care of policy and standards whereas manufacturers are to ensure built-in security features for IoT devices. They are of the view that IoT device owners (or consumers) should be given the authority to collect, share and use the data as well as take ownership of the data. The organisations deemed as trustworthy were the government and regulatory agencies (78.4%).

Figure 4.

Perceptions towards secured data governance and ecosystem.

The interviews provide indications and a way forward in addressing issues related to the establishment of effective IoT data governance. According to the experts, there is a vast array of critical cybersecurity issues that need to be rectified first. These include: the weak and unorganised institutional and regulatory framework; lack of adaptive capabilities and capable staff in cybersecurity; and lack of priority, enforcement, and transparency. In order to strengthen the IoT data governance, the fundamentals should be: strengthening consumer education and smart partnership between government-industry-civil society; motivation for active participation of NGOs and civil society; and obtaining industry buy-in and GDPR principles of fair information practices. Eventually, the regulatory framework for IoT data governance should encompass targeted intervention, accountability of regulation and responsibility of business, and standard compliance. The regulatory framework should be constructed as a response to the cybersecurity issues and be optimised on the fundamentals (or drivers) developed by the various stakeholders.

6. Discussions

We have an older generation that when they hear ‘technology’, they have a mental block. The younger generation understand technology, but they may not have security or safety in mind (EXR2). In this increasingly high-technology world, almost everybody owns a smart device regardless of age, gender, educational background, etc. Therefore, it is important that adequate protection be afforded to all IoT users. Our findings highlight the need for a comprehensive governance framework, the potential of which will be discussed in this section.

6.1. IoT Data Governance Institution

Basically, regulatory frameworks include regulations, laws, rules, guidelines or codes of practice. As these frameworks are developed to achieve designated policy goals, there are two categories of actors or stakeholders involved, namely: (a) those subject to the regulation or developing, enforcing or monitoring the regulation; and (b) those who stand to benefit from or face impacts from the regulation. One of the main issues of IoT governance—as witnessed in the case of Malaysia—is the lack of coordination mechanisms between the different regulatory bodies and agencies. This is also the case with public awareness and education, whereby efforts are carried out in a disjointed and separate manner. It is interesting to observe the different approaches the various regulatory authorities have—perhaps their approaches differ based on their organisational culture and outlook. For example, in a private organisation, there may be a reluctance to share resources and cooperate on joint awareness efforts. This may stem from a need to prove the organisation’s performance and, thus, continued relevance, instead of putting on a united front the way the civil service does (from a macro perspective). This would prove interesting to investigate in further studies.

The case of Malaysia supports the need for a higher authority to coordinate efforts among stakeholders. Perhaps a solution would be to provide a coordinating mechanism between the various parties. On several occasions during the interviews, it was advised that a national-level and leading agency to realise national cybersecurity policy and management in a cohesive and holistic manner—such as NACSA—should be empowered for this purpose. This includes coordinating and harnessing experts and resources at a national level. However, such a role is not outlined in any legislation—according to the experts interviewed, this hinders their role significantly. Therefore, it is suggested that NACSA be rebranded and established through its own Act, the National Cyber Security Agency (NACSA) Act. This Act will also provide for more adequate and skilled manpower to play a more important role in safeguarding national cybersecurity, as well as IoT and personal data protection. Furthermore, as the PDPA does not extend to government data, issues arise over the mechanism to tackle government data breaches. Handling these breaches in a structured manner is important in order to safeguard public trust and further the government’s e-agenda. Tasking NACSA with this may be suitable, as it involves high level public interest.

In terms of obtaining cooperation and support from the private sector, it was suggested that non-legislative measures may be used to promote awareness and shared responsibility among industry players, a point which is also postulated by Shin [68]. It is a known fact that the private sector is largely motivated by their bottom line, therefore the use of non-legislative measures, such as financial incentives, may provide a win–win situation for all parties. This could be in the form of tax incentives or awards/acknowledgements. Similar to energy efficiency ratings, a privacy rating may be developed for IoT consumer products. This will assist consumers to make informed choices and indirectly affect change in the industry.

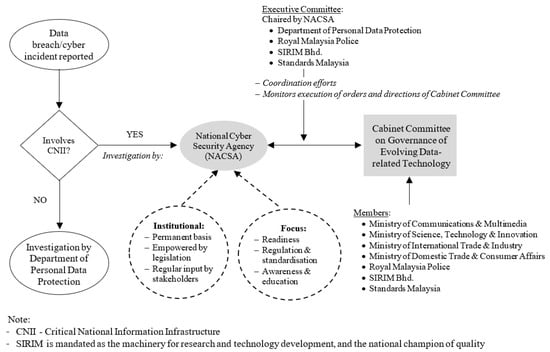

As the issues surrounding IoT and personal data protection in Malaysia cut across several ministries and government departments—and the need for an authority body to coordinate efforts among stakeholders was highlighted in the expert interviews—it is suggested that a Cabinet Committee be formed. Such a committee serves the purpose of facilitating in-depth analysis of policy matters and coordination between different stakeholders. The principles that are applicable here are teamwork and division of labour in order to effectively and efficiently tackle a particular issue. Cabinet Committees have been utilised in the past to overcome national issues that are deemed complicated and require urgent attention. These can be either permanent or ad hoc. Some examples of cabinet committees formed in the past include: the Cabinet Committee on National Food Security Policy; the Special Cabinet Committee on Anti-Corruption (JKKMAR); and the Cabinet Committee on the Eradication of Drugs (JKMD). In the context of Malaysia, Figure 5 illustrates a proposed structure on the governance of evolving data-related technology—particularly if data breaches or cyber incidents are reported. In this proposed framework, NACSA is empowered by legislation and supported by multiple stakeholders to perform its leading role in cybersecurity (and data governance).

Figure 5.

Proposed structure on the governance of evolving data-related technology in Malaysia.

6.2. Collective Responsibility and Practical Implications

IoT and its application in Malaysia are still in the initial stages. Therefore, it is important that the performance of any implemented regulatory measures is progressively examined in practical application. This needs to be systematically conducted based on the outlined regulatory objectives. It is unlikely that any regulatory measures taken will be able to resolve all problems. Therefore, the regulations developed need to be flexible and adaptable to the rapid advancements in technology.

As a newcomer in IoT, countries like Malaysia may look to developed countries (or pioneers in IoT) to jump start the initiatives. As the EU GDPR has influenced the development of the personal data protection regulations in Malaysia including the PDPA, it is reasonable to expect that the key concerns on consumer data privacy (such as privacy-by-design) may be adopted to suit local requirements. This will include updating of existing regulations that are needed in order to address the new threats, and stricter measures when dealing with data breaches. Furthermore, there are some gaps in the PDPA that need to be addressed, for example, instances where data that are processed overseas or handled by a third-party data processor is breached. Non-commercial transactions, such as phone applications and social media, also need to be included in the PDPA.

It also needs to be recognised that attacks at an individual level could potentially escalate to organisational and national level threats. Therefore, there is a need to regulate IoT devices and set industry standards. However, any regulatory changes need to be balanced and dynamic in order to prepare for fast evolving technology. The government and regulatory agencies face lack of resources and knowledge to conduct enforcement activities. Therefore, it was highlighted that there needs to be a whistleblowing mechanism and the establishment of a working relationship between the regulators and the cyber world. This will allow for joint and complementary actions, in which the collective responsibility among the various stakeholders (e.g., regulators, industries, NGOs, civil society, consumers, etc.) is the key operating principle that would allow for increased commitment and participation from the stakeholders towards a common goal. Figure 5 shows the model of collective responsibility in IoT data governance. The three elements—fair information practices, privacy impact assessment, and privacy accountability—are indeed key principles of EU GDPR.

As shown in Figure 6, the collaborative model is supported by four drivers: (a) Consumer awareness and education; (b) Industry accountability and responsibility; (c) Regulatory institutions; and (d) Regulatory framework. Broad strategies necessary to strengthen these drivers in the quest to achieve clear and coherent IoT data governance can be summarised in Table 6. It is anticipated that with the adoption of these strategies and approaches, a more holistic ecosystem for IoT and personal data protection may be put in place. However, implementing these strategies will require the commitment of all stakeholders—and therein lies the challenge. Resistance to change and lack of transparency in sharing information between the various stakeholders may be some of the challenges faced. Furthermore, as observed in the current incidents of data breaches whereby the larger and more impactful ones have been from the government sector, there may be reluctance from the other sectors to take these strategies seriously unless the government ‘walks the talk’ by demonstrating better data governance practices.

Figure 6.

Collective responsibility model of IoT data governance.

7. Limitations and Ethics

In conducting the research, the following limitations were observed:

- The research deals with a topic that is not well known in Malaysia. Therefore, whilst the problems and issues discussed are well known in developed countries, the full impact of the risks involved in consumer IoT and personal data protection is not realised by the respondents and expert interviews;

- The research framework was developed along the course of the research. This was because the research was exploratory and there was limited local knowledge on the subject matter. This led to “snowballing” in terms of data collection. Toward the tail end of the research, there were several more data breaches and this has caused increased awareness and reporting on the subject matter;

- The respondents and interviewees were from middle or upper class, educated, fluent in English, and IT savvy backgrounds. This may have influenced their perception of the issues to do with IoT and personal data protection. This may not be the case with different groups of people.

The survey data captured in this study will fast become obsolete as IoT is a fast-emerging field. Customers’ expectations, behaviours, and expression on IoT devices and ecosystem are expected to change in a short period of time. As per the requirement by Universiti Malaya (UM), the framework of this research was submitted to the Universiti Malaya Research Ethical Committee (UMREC) and approval was obtained. In both instruments (survey and expert interviews), care was taken to ensure that the respondent’s information was kept private and safe as per the UMREC requirements. This includes the way the information was stored and codified. Informed consent was also a critical part of ensuring the research was ethically sound, whereby survey respondents were required to click a square checkbox button stating that they had read the information sheet and consent to the study; and the expert interviewees were required to read the information sheet and sign their consent prior to the interview. In both instruments, respondents/interviewees were above 18 years old; therefore, parental consent was not applicable.

8. Conclusions

Through the course of this research, many issues have been revealed—providing new knowledge to bridge the existing gaps. These include the need for adequate resources and investment as well as prioritising security. Equally important is the urgency in regulating IoT—as with the increase of connected devices, it is anticipated that the data privacy risks will also increase exponentially. This paper proposes a collaborative model that incorporates the roles of the key stakeholders. The role of the government can be seen from the regulatory and institutional supports. Any regulatory changes need to be phrased carefully and communicated to stakeholders in order to address mindset changes and allow time for businesses to adjust. The government will need to step up their moderator role and increase engagement and awareness on this matter. Industry, on the other hand, can play their role by incorporating privacy values into their business practices—e.g., fair information practices, privacy impact assessment, and privacy accountability. Furthermore, personal data protection should be seen as a priority which could disrupt business continuity. Awareness programmes and the number of touchpoints with consumers as well as businesses needs to be increased. In this aspect, there is a need for industry to share some responsibility and accountability in creating awareness. The reach of awareness programmes can also be increased by empowering civil society groups and consumers. Whilst there are limitations with having a data governance model be driven by the regulators (government), it is the right step in initiating more industry and civil society involvement and participation. These findings can be used as a basis for IoT data governance policy or regulation review in the near future. This research has contributed to better understanding on the importance of mitigating and managing risks related to IoT devices, which may be applied to other emerging technology in developing countries. In terms of future research, responses from the other segments of society including the rural communities and lesser educated groups could be incorporated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.-K.C. and B.-K.N.; Data curation, B.-K.C.; Formal analysis, B.-K.C.; Methodology, B.-K.C. and B.-K.N.; Supervision, B.-K.N.; Visualization, B.-K.N.; Writing—original draft, B.-K.C. and B.-K.N.; Writing—review and editing, B.-K.C. and B.-K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the research ethics clearance approved by the Universiti Malaya Research Ethical Committee (UMREC) (No. UM.TNC2/UMREC-591).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wong Chan-Yuan for his constructive comments on the earlier version of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Examples of Survey Questions on Public Perception on IoT and Personal Data Protection in Malaysia

- Section on IoT and Personal Data Security.

- 1.

- Are you aware of the recent data breaches in Malaysia (i.e., the incidence of data breach of Uber or/and Telco data)?

- Yes

- No

- Not sure

- 2.

- How do you feel knowing that your personal data may be at risk? _________________________

- 3.

- What do you think is the MOST IMPORTANT role of IoT device manufacturers in order to provide adequate personal data protection for the consumer?

- Engagement with stakeholders (i.e., consumers, regulators or government bodies)

- Proactive monitoring of threats

- Transparency and quick handling of any breach

- Built-in security features for IoT devices

- Others (please mention): ____________________

- 4.

- What do you think should be the MOST IMPORTANT role of the regulators [i.e., government bodies such as Suruhanjaya Komunikasi dan Multimedia Malaysia (SKMM) or the Jabatan Perlindungan Data Peribadi Malaysia (JPDP)]?

- Coordination between stakeholders (i.e., consumers or manufacturer)

- Proactive monitoring of threats

- Transparency and quick handling of any breach

- Developing and implementing of policy and standards on IoT devices

- Others (please mention): ____________________

- Section on privacy-by-design model.

- 5.

- What do you think of the concept of “privacy-by-design”? Do you think it will be suitable to be implemented in Malaysia?

- Yes

- No

- Not sure

- 6.

- Please specify reasons (optional) __________________

- 7.

- As a consumer, if you were choosing between two brands of smart watches, Brand A and Brand B, please choose THREE (3) most favoured characteristics that will influence your decision*

- Price

- Additional Features (e.g., customisable watch faces for smart watch or social networking for smart TV)

- Data protection

- Brand/ Reputation/Trust

- Long-lasting

- Product support throughout lifecycle

- Design and attractive look

- Current trends/fashion

- Consumer involved in product development

- Others

- 8.

- Should companies incorporate privacy by design with price increase, do you think you would still buy the product?

- Yes

- No

- Not sure

- 9.

- Please specify reasons (optional): ________________

- Section on consumer data governance: Smart Watches brands like Apple or Fitbit collect consumer health data including activity levels and heart rate through sensors.

- 10.

- Based on the statement above, who do you think has the most authority to collect, share and use data?

- IoT Device owner/consumer (e.g., yourself)

- IoT Device manufacturer (e.g., Apple/ Fitbit)

- Third party Internet and data storage partners (e.g., Telco)

- Regulatory agencies (e.g., SKMM)

- Others

- 11.

- Based on the statement above, who do you think has the MOST RIGHT to own the data collected by IoT devices? Please select the most relevant answer.

- IoT Device owner/consumer (e.g., yourself)

- IoT Device manufacturer (e.g., Apple/ Fitbit)

- Third party Internet and data storage partners (e.g., Telco)

- Regulatory agencies (e.g., SKMM)

- Others

- 12.

- In your opinion, who should be championing IoT data protection in Malaysia?

- Government (e.g., SKMM)

- Industry (e.g., IoT device manufacturers/Telcos)

- Civil society (consumer associations, NGOs)

- Others, please specify

Appendix B

Table A1.

Main themes of cybersecurity readiness issues.

Table A1.

Main themes of cybersecurity readiness issues.

| Theme | Empirical Evidence |

|---|---|

| Institutional and legal instruments | Without legal instruments, it’s difficult to instruct any organisation. All the regulatory agencies have their own laws, so they are more concerned about their own laws (EXR1). Because of legacy issues, everybody claims to be doing cybersecurity…… we hope there will be better coordination between all the entities (EXR2). The current regulation is still lacking to cater for new technology and devices in handling huge data…… there needs to be a balance between innovations that we want to spur and the data that needs to be exposed (EXI1). It’s good not to put so much restriction on the industry. Also, don’t suddenly introduce regulations that may stifle industries that have been running for several years already (EXI1). With IoT the attack could come from a personal device and through that to the banks which would be a national level security issue. (EXR2). MCMC, NACSA and JPDP are interrelated because most of the cyber security issues are related to data, personal data or trade data (EXR1). |

| Adaptive capabilities and capable staff | The trend is moving so fast; the regulators have the challenge to keep up with the technology (EXI1). For the last few years, Malaysia has been ranked top 10 in terms of the government’s commitment in implementing cybersecurity measures. However, it seems that other countries are bucking up. They are actually improving strategies while Malaysia remains as it is (EXR5). Government experts are very limited in the field of ICT security. Government needs to invest in terms of people and think about how to retain talent at a place where they can grow. It’s not only the information technology scheme but the lawyers specializing in cyber security (EXR2). In terms of cybersecurity readiness, institutionally and regulatory wise, we are positioned quite well globally. However, challenges are in terms of coordination and leadership and readiness for government and industry to share information (EXR3). EU GDPR has cross border implication. Malaysia cannot run away from that. PDPA needs to be amended to adapt to the higher standards (EXI2). |

| Priority setting, enforcement and transparency | Everyone who works in the security environment needs to be trustworthy. Awareness should be right from the top of the organization and they need to allocate certain budget for security (EXI1). From the company’s point of view, cybersecurity is the least of their investment, the focus is more on operating the system (EXR4). Enforcement still has a lot of work to do. Despite several significant data breach incidents, there doesn’t seem to be much enforcement action taken. (EXI2). Organisations are not transparent if they are in a situation where they encounter breaches. They report only if they can’t handle it anymore (EXR3). Especially personal data like phone, credit card, address, etc. Leaking this information is unforgiveable. Therefore, the regulatory agencies should penalise harshly these organisations that leak the data whether intentionally or not (EXI1). |

Source: Authors’ interviews.

Appendix C

Table A2.

Main themes of data governance fundamentals.

Table A2.

Main themes of data governance fundamentals.

| Theme | Empirical Evidence |

|---|---|

| Consumer education and smart partnership | Consumers themselves need to be empowered, and I think not enough is being done for consumer education (EXC2). There needs to be a partnership between government, industry and civil society to empower people (EXC2). There’s a lot of watch dogs... third party organisations such as privacy protection type of agencies or NGOs...I think they play a key role (EXI4). But we don’t see any major strategy or systematic approach in educating and empowering consumers to deal with this (EXC2). Awareness can be increased through education. But we need to be careful not to encourage fear of technology (EXI1). Data users need to take practical steps as outlined in PDPA. This is very subjective. So, the burden becomes on the tech companies to prove that they have taken the necessary steps (EXI2). If they increase engagement, increase the number of touchpoints with consumers as well as businesses, you can see the acceptance rate will roughly increase (EXI4). |

| Active participation of NGOs and civil society | Civil society brings credibility and the ability to reach the community. The regulators should work with civil society to reach the consumers. Whether it’s schools, whether it’s communities or young workers (EXC2). There is need to engage a lot of local communities and government itself cannot do so, so they can empower or work with agencies, NGOs and community groups in order to spread the word around (EXI4). Integrate all the awareness initiatives. Because awareness is expensive. Some private entities are doing their own advocacy. Repository of awareness materials. Share the materials and send the same message to the people (EXR2). Whistleblowing—there are communities that follow news and inform (EXR2). |

| Industry buy-in and fair privacy practices | Companies can adhere as long as we understand what the principles are and measures that need to be put in place (EXI4). None of the products really focus on enlightening you….. Very much the consumers are left on their own (EXC2). Data protection should be included for the earliest stages from the development of the business model. You need to determine who owns the data etc. and plan your business around it (EXI1). Government should put in regulation to ensure that tech companies are transparent about how data is being handled and practice fair privacy practices (EXI2). It should be the responsibility of the organisation to make sure they collect the right amount of data for the right purpose rather than collect as much data as they can (EXI4). If you want to protect your data, you need to check how you protect it, who is the provider of the solution. The owner of the data is responsible, all these needs to be spelled out in the Service Level Agreements (SLA). Security requirements needs to be spelled out clearly (EXR2). |

Source: Authors’ interviews.

Appendix D

Table A3.

Main themes of regulatory frameworks.

Table A3.

Main themes of regulatory frameworks.

| Themes | Empirical Evidence |

|---|---|

| Targeted intervention | It is totally inadequate to deal with the current personal data leakages. I think definitely the current legislation deals with physical but this is happening at a whole different level (EXC2). We are over focused on growth... but we are in the terrain where it’s tough for consumers to protect themselves. So, we are depending on the regulators to a large extent (EXC2). It should not be necessary for the regulators to intervene all the time. If we have a standard code of practice, the industry should be able to follow (EXR3). |

| Accountability of regulation and responsibility of business | Actually, there can’t be third party... If a business uses a third party for their business, they still need to be responsible that our data is protected and only data processed related to the purpose (EXC2). Businesses have to think of ways in which they can ensure that consumer data is protected (EXI4). Board to declare their cyber security risks. Security should be seamless and embedded to the user. Not an option to user but a requirement (EXR2). In GDPR, the data processor is included whilst in PDPA it is excluded. Therefore, the contract between data user and processor needs to be compliant to PDPA (EXR1). |

| Standards setting and compliance | The commission or MCMC plays a key role in ensuring that only the right type of equipment is brought into Malaysia... that meets and conforms to our minimum standards that Malaysia has set. Having said that, I think whilst Malaysia may set certain standards, we also need to adhere to international standards (EXI4). I mean there are already certification processes for normal products. Because of the lack of capability of consumers to protect themselves, the regulators have to play a bigger role (EXC2). Government needs to have standards and specifications in place to ensure security at all points (EXI1). Most of the companies involved in the pilot projects are supplying to MNCs. As such if they don’t comply to international standards, they may have issues with their MNCs (EXR4). |

Source: Authors’ interviews.

References

- Lee, I.; Lee, K. The Internet of Things (IoT): Applications, investments, and challenges for enterprises. Bus. Horiz. 2015, 58, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Salah, K. IoT security: Review, blockchain solutions, and open challenges. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 82, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-P.; Huang, T.C.-K.; Wang, S.-T. The impact of Internet of things implementation on firm performance. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 2038–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzori, L.; Iera, A.; Morabito, G. The internet of things: A survey. Comput. Netw. 2010, 54, 2787–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkina, A.; Illiashenko, O.; Zhydenko, M.; Uzun, D. Cybersecurity of healthcare IoT-based systems: Regulation and case-oriented assessment. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 9th International Conference on Dependable Systems, Services and Technologies (DESSERT), Kyiv, Ukraine, 24–27 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hogewoning, M. IoT and regulation–striking the right balance. Netw. Secur. 2018, 2018, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Kar, A.K. Regulation and governance of the Internet of Things in India. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2018, 20, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ruithe, M.; Mthunzi, S.; Benkhelifa, E. Data governance for security in IoT & cloud converged environments. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/ACS 13th International Conference of Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA), Agadir, Morocco, 29 November–2 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart, L.; McAuley, D. Avoiding the internet of insecure industrial things. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2018, 34, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, C.; Zaslavsky, A.; Christen, P.; Georgakopoulos, D. Context aware computing for the internet of things: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2014, 16, 414–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kawamoto, Y.; Nishiyama, H.; Kato, N.; Yoshimura, N.; Yamamoto, S. Internet of Things (IoT): Present state and future prospects. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2014, 97, 2568–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ASEAN Secretariat. ASEAN Human Rights Declaration and the Phnom Penh Statement on the Adoption of the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (AHRD); ASEAN Secretariat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cheryl, B.-K.; Ng, B.-K.; Wong, C.-Y. Governing the progress of internet-of-things: Ambivalence in the quest of technology exploitation and user rights protection. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.M.; Kiel, D.; Voigt, K.-I. What drives the implementation of Industry 4.0? The role of opportunities and challenges in the context of sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalsoom, T.; Ahmed, S.; Rafi-Ul-Shan, P.M.; Azmat, M.; Akhtar, P.; Pervez, Z.; Imran, M.A.; Ur-Rehman, M. Impact of IoT on manufacturing industry 4.0: A new triangular systematic review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, S.H.; Silva, H.R.O.; Terra da Silva, M.; Gonçalves, R.F.; Sacomano, J.B. Industry 4.0 and sustainability implications: A scenario-based analysis of the impacts and challenges. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carr, M.; Lesniewska, F. Internet of Things, cybersecurity and governing wicked problems: Learning from climate change governance. Int. Relations 2020, 34, 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katherine-Chen, Y.-N.; Ryan-Wen, C.-H. Taiwanese university students’ smartphone use and the privacy paradox. Comunicar 2019, 27, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, M.D.; Bogdanov, E. Privacy in doubt: An empirical investigation of Canadians’ knowledge of corporate data collection and usage practices. Can. J. Adm. Sci. Rev. Can. Sci. l’Adm. 2019, 36, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.D.; Blythe, J.M.; Manning, M.; Wong, G.T.W. The impact of IoT security labelling on consumer product choice and willingness to pay. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, Y. Conceptualising the right to data protection in an era of Big Data. Big Data Soc. 2017, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albalawi, A.M.; Almaiah, M.A. Assessing and reviewing of cyber-security threats, attacks, mitigation techniques in IoT environment. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2022, 100, 2988–3011. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, K. That’Internet of Things’ thing. RFID J. 2009, 22, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R.; McMahon, E.; Samtani, S.; Patton, M.; Chen, H. Identifying vulnerabilities of consumer Internet of Things (IoT) devices: A scalable approach. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (ISI), Beijing, China, 22–24 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, Q.; Vasilakos, A.V.; Wan, J.; Lu, J.; Qiu, D. Security of the internet of things: Perspectives and challenges. Wirel. Networks 2014, 20, 2481–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-I.; Chang, L.-M.; Liao, J.-C. Risk factors of enterprise internal control under the internet of things governance: A qualitative research approach. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karygiannis, T.; Eydt, B.; Barber, G.; Bunn, L.; Phillips, T. Guidelines for securing radio frequency identification (RFID) systems. NIST Spec. Publ. 2007, 80, 1–154. [Google Scholar]

- Dawy, Z.; Saad, W.; Ghosh, A.; Andrews, J.G.; Yaacoub, E. Toward Massive Machine Type Cellular Communications. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2016, 24, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.-L.; Liu, F.; Liang, Y.-D. A Survey of the Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on E-Business Intelligence (ICEBI), Online, 19–21 December 2010; pp. 358–366. [Google Scholar]

- Kavianpour, S.; Shanmugam, B.; Azam, S.; Zamani, M.; Samy, G.N.; De Boer, F. A Systematic Literature Review of Authentication in Internet of Things for Heterogeneous Devices. J. Comput. Networks Commun. 2019, 2019, 5747136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neisse, R.; Baldini, G.; Steri, G.; Mahieu, V. Informed consent in Internet of Things: The case study of cooperative intelligent transport systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 23rd International Conference on Telecommunications (ICT), Thessaloniki, Greece, 16–18 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Conner, L.G.; Gill, R.A.; O’Connor, R. Connecting to the Data-Intensive Future of Scientific Research. 2013. Available online: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/spacegrant/2013/Session2/2/ (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Cavoukian, A. Privacy by Design: The 7 Foundational Principles. January 2011. Available online: https://iapp.org/media/pdf/resource_center/pbd_implement_7found_principles.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Philipp, A.J. How the GDPR will change the world. Eur. Data Prot. Law Rev. EDPL 2016, 3, 287–289. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, M. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): European Regulation that has a Global Impact. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 59, 703–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]