Factors Affecting Visiting Behavior to Bali during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

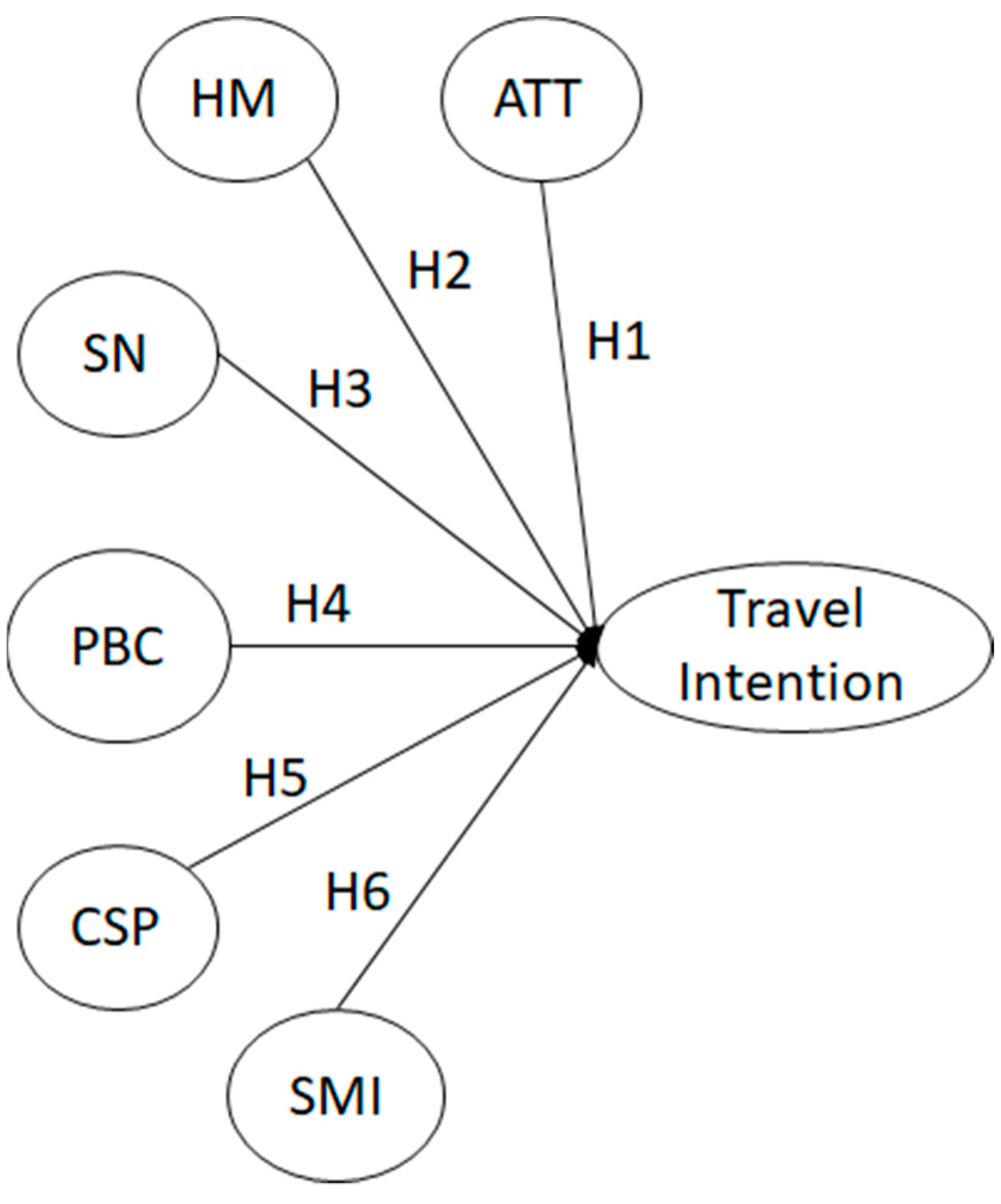

2. Theoretical Framework

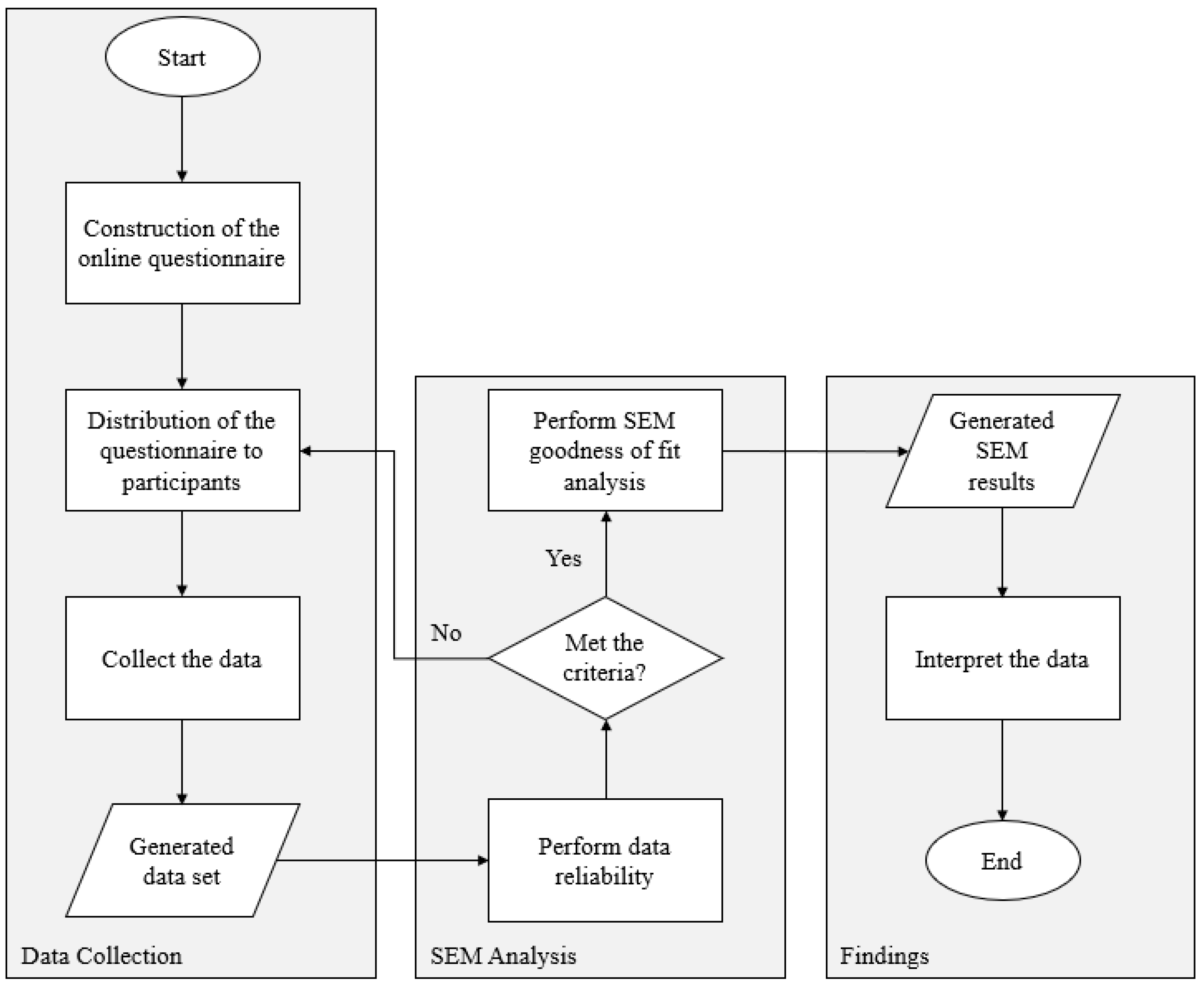

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Questionnaire

3.3. Statistical Analysis

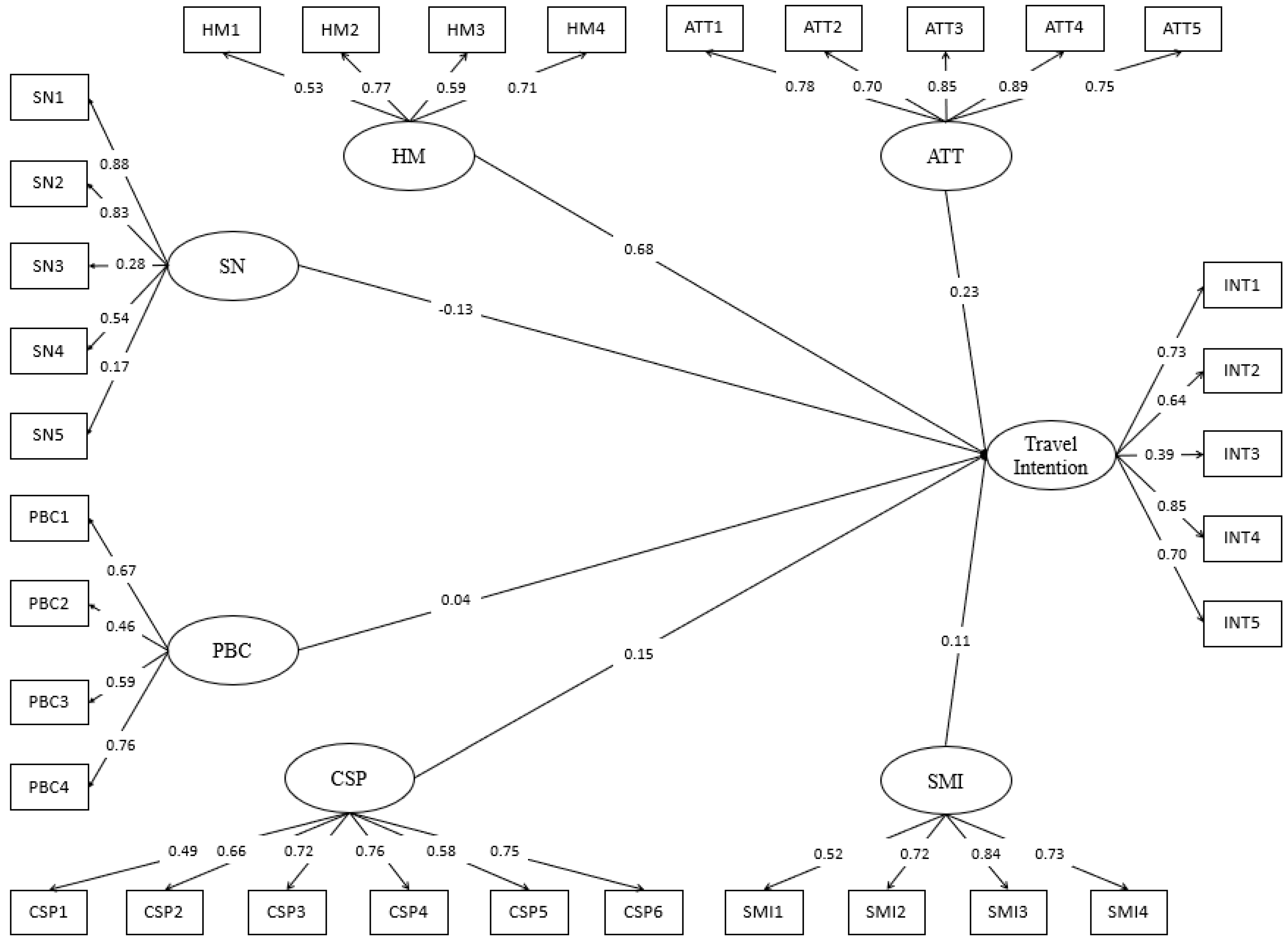

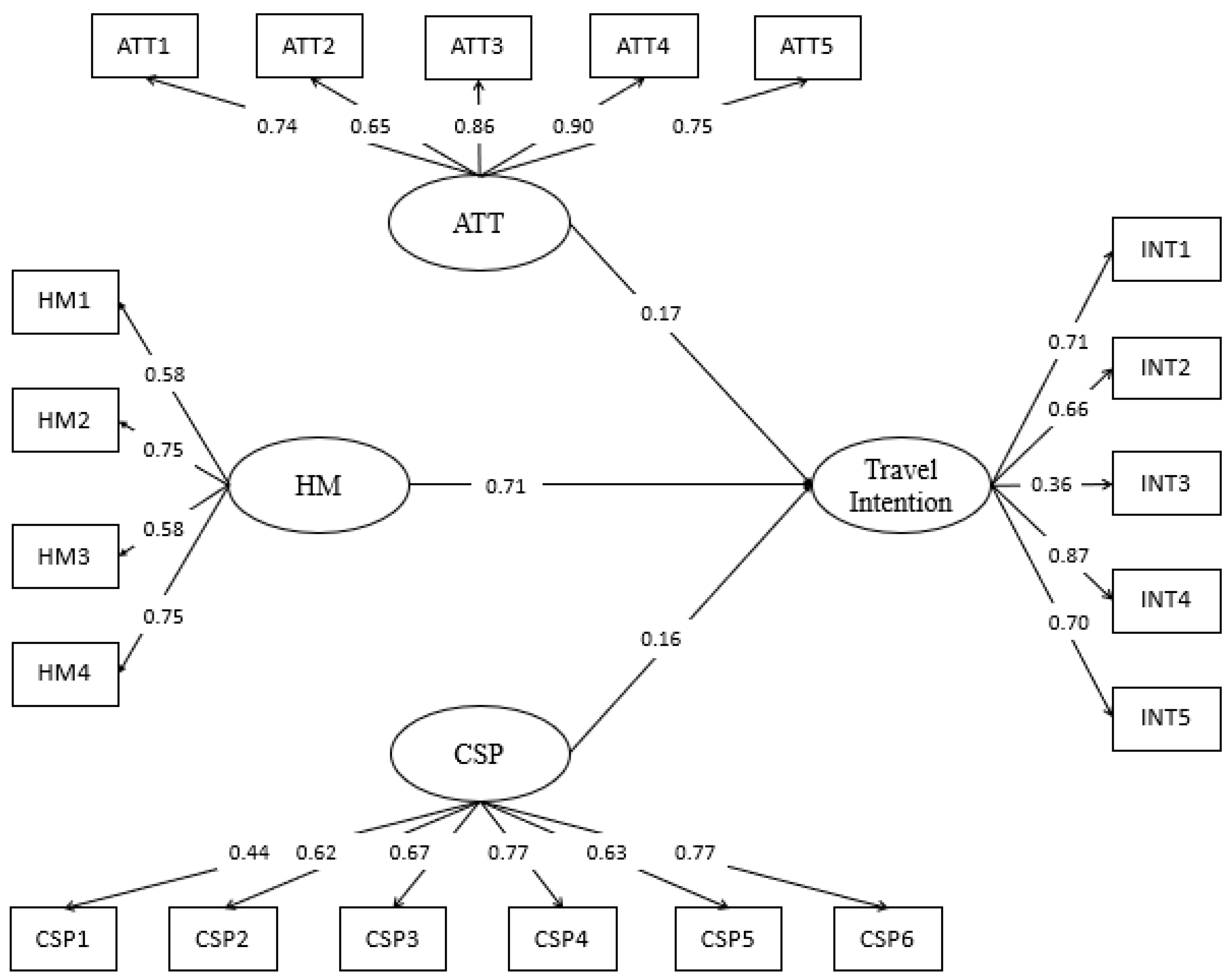

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. General Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

- (1)

- Bali’s tourism stakeholders must fulfill the tourist’s positive emotions and experiences by providing leisure activities that enhance the aforementioned feelings. Leisure activities include island hopping, snorkeling, diving, water sports, and trekking. Majestic manmade spots must be offered to tourists for photo opportunities because it would also enhance positive emotions; many tourists take pictures in beautiful sceneries. Since hedonic motivation significantly impacted tourist’s visiting intention, the researchers recommend stimulating positive emotions of tourists. Tourism stakeholders must provide additional services to tourists, like photography, private transportation, and meals and drinks.

- (2)

- Bali’s tourism stakeholders should create an ambiance to relieve travelers’ stress because tourists want to destress by traveling to Bali. It was encouraged to formulate events that promote the balance between solemnity and enjoyment. For instance, businesses must invite performers to dance and sing. Sports performances are also needed to cover different preferences of tourists. These events should be diverse every day to ensure that tourists experience novelty. The study emphasized that hedonic motivation consisted not only of positive emotions but also the enticement to new experiences.

- (3)

- The current findings reflected the significant importance of COVID-19 protocols when visiting Bali. All tourists, residents, and businesses’ employees must rigorously follow COVID-19 protocols to ensure that everyone is safe from the virus. COVID-19 protocols include safe distancing, participating in the vaccination program, and usage of face masks and sanitizers. Tourists did not want to feel too cautious while on vacation due to the COVID-19, hence all tourists must do their part. The researchers also suggested that stakeholders prepare printed posters and recorded videos entailing COVID-19 protocols to be shown to tourists of each destination place. Another recommendation was to play audio recordings intermittently stating the COVID-19 protocols to help remind tourists.

- (4)

- People recognize the criticality of getting infected by the COVID-19, but they do not want any burdensome rules. Hence, removing the PCR test and quarantine period was recommended for fully vaccinated individuals. Vaccinated people are less likely to get infected and decrease the probability of spreading the virus to others [45]. Meanwhile, non-vaccinated tourists must present a negative swab test result, and a quarantine period must be maintained. In this study, participants praised people who sanitized, used face masks, and were vaccinated. The ports and airlines connected to Bali should ensure that all passengers follow Bali’s COVID-19 protocols. Once tourists are in Bali, accommodation places should make COVID-19 protocols mandatory all the time. Tourism stakeholders must ensure that tourists wear face masks when walking around the island and destination places. Every closed-space establishment must have temperature checks and hand sanitation.

- (5)

- Tourist accommodations (hotels and villas) need to enhance their services (e.g., reduced noise, improved cleanliness, food and beverage) to contribute to tourist’s comfort. Based on the study’s findings, safety, health, and cleanliness must be the top priority of accommodation stakeholders. The accommodation room must be sanitized every time a new tourist uses it. For example, bed sheets, pillow sheets, comforters, and towels should always be changed. Appliances should be sanitized, too. Also, there should be a regular sanitation check throughout the accommodation because tourists tend to explore outside their rooms. Moreover, interaction with Balinese was a strong indicator for tourists since Balinese people are known for their friendly personality. Hence, customer service must be maintained and provided to local and international tourists. Establishment’s staff and tourist guides were encouraged to check their customers occasionally to ensure they were enjoying their stay in Bali. It was disclosed that travelers need good rest and social interactions [46]. Likewise, participants of the current study want to create good memories during their vacation.

- (6)

- The destination tour map must be improved by presenting destination mapping to each tourist. Tourism stakeholders should offer customized itineraries according to the preferences of tourists. This approach would help increase the tourist’s hedonic motivation, consisting of positive emotions and novelty value. For example, some tourists prefer historical explorations to sports activities. Thus, these tourists should be invited to explore Bali’s temples. Another instance is when one group of tourists may prefer island hopping but some types of tourists like trekking. Tourists should be given multiple options, given that most of them stay in Bali for at least a day. One study stated that tourists’ travel plans must reflect their personalities and characteristics [46].

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hotle, S.; Murray-Tuite, P.; Singh, K. Influenza risk perception and travel-related health protection behavior in the US: Insights for the aftermath of the COVID-19 outbreak. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 5, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamaluddin, M.; Marcus, L. Bali Only Received 45 International Tourists in 2021 Despite Reopening. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/bali-tourism-collapse-2021-intl-hnk/index.html (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Bhaskara, G.I.; Filimonau, V. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Organisational Learning for Disaster Planning and Management: A Perspective of Tourism Businesses from a Destination Prone to Consecutive Disasters. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsham, L. Bali Is Open to International Tourists: Here’s All You Need to Know about Visas, Quarantine and PCR Testing. Honeycombers Bali. 28 May 2022. Available online: https://thehoneycombers.com/bali/bali-borders-re-opening-plan/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Deutsche Welle. Bali Tourism Industry Struggling with COVID-19: DW: 25.12.2021. DW.COM. 25 December 2021. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/bali-tourism-industry-struggling-with-covid-19/av-59984174 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Teja, N. Bali’s Economy Struggles to Survive Without Tourists: ASEAN Today. ASEAN Today|Daily Commentaries Covering ASEAN Business, Fintech, Economics, and Politics. 12 October 2020. Available online: https://www.aseantoday.com/2020/10/balis-economy-struggles-to-survive-without-tourists/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Wachyuni, S.S.; Kusumaningrum, D.A. The effect of COVID-19 pandemic: How are the future tourist behavior? J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2020, 33, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembada, A.Y.; Kalantari, H.D. Biting the travel bullet: A motivated reasoning perspective on traveling during a pandemic. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 103040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemy, D.M.; Nursiana, A.; Pramono, R. Destination loyalty towards Bali. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, L. Consumer behaviour in tourism. Eur. J. Mark. 1987, 21, 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, L.P. Does social media influence consumer buying behavior? An investigation of recommendations and purchases. J. Bus. Econ. Res. JBER 2013, 11, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, W.J.; Kim, Y.H. Does VR Tourism Enhance Users’ Experience? Sustainability 2021, 13, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H. Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, R.; Woodside, A.G. Testing theory of planned versus realized tourism behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 905–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girish, V.G.; Lee, C.-K.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, Y.S. Impacts of Perception and Perceived Constraint on the Travel Decision-Making Process during the Hong Kong Protests. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2093–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Cui, M. The Role of Co-Creation Experience in Forming Tourists’ Revisit Intention to Home-Based Accommodation: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoglu, B.B.; Bilgihan, A.; Ye, B.H.; Buonincontri, P.; Okumus, F. The Impact of Servicescape on Hedonic Value and Behavioral Intentions: The Importance of Previous Experience. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sreen, N. Role of internal and external values on green purchase. In Green Marketing as a Positive Driver Toward Business Sustainability; IGI Global: New York City, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 158–185. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, S.; Talhelm, T.; Lee, M. Personality and Geography: Introverts Prefer Mountains. J. Res. Personal. 2015, 58, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jakarta Post. From Sweeping to Digging, Indonesia Gets Creative in Handling Violators of COVID-19 Protocols. Available online: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/09/17/from-sweeping-to-digging-indonesia-gets-creative-in-handling-violators-of-covid-19-protocols.html (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Chew, E.Y.; Jahari, S.A. Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post-disaster Japan. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhayati-Wolff, H. Indonesia: Social Media Market Share 2021. Statista. 24 August 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1256213/indonesia-social-media-market-share/ (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Muñoz-Fernández, G.; Fuentes-García, F.J. Impact of the perceived risk from COVID-19 on intention to travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borhan, M.N.; Ibrahim, A.N.H.; Miskeen, M.A.A. Extending the theory of planned behaviour to predict the intention to take the new high-speed rail for intercity travel in Libya: Assessment of the influence of novelty seeking, trust and external influence. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 130, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, H.; Li, Y.; Amin, A. Factors influencing Chinese residents’ post-pandemic outbound travel intentions: An extended theory of planned behavior model based on the perception of COVID-19. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 871–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.Y.; Chang, P.-J. The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic (March 2020). Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, B.-H.; Hong, C.-Y. Does Risk Awareness of COVID-19 Affect Visits to National Parks? Analyzing the Tourist Decision-Making Process Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biran, A.; Liu, W.; Li, G.; Eichhorn, V. Consuming post-disaster destinations: The case of sichuan, China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 47, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Das, S.S.; Tiwari, A.K. Understanding international and domestic travel intention of Indian travellers during COVID-19 using a Bayesian approach. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 46, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Peng, Z.; Cai, X.; Peng, Y.; Li, J.; Feng, T. Students’ intention of visiting urban green spaces after the COVID-19 lockdown in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahigas, M.M.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Persada, S.F.; Ong, A.K.; Nadlifatin, R. Understanding the perceived behavior of public utility bus passengers during the era of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines: Application of social exchange theory and theory of planned behavior. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 100840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Jia, G.; Hou, Y. Impulsive travel intention induced by sharing conspicuous travel experience on social media: A moderated mediation analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Castillo, A.M.; Salonga, L.J.; Sia, J.A.; Seneta, J.A. Factors affecting perceived effectiveness of COVID-19 prevention measures among Filipinos during enhanced community quarantine in Luzon, Philippines: Integrating Protection Motivation Theory and extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 99, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.; Boudreau, M.-C. Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steiger, J.H. Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilashi, M.; Ali Abumalloh, R.; Alrizq, M.; Alghamdi, A.; Samad, S.; Almulihi, A.; Althobaiti, M.M.; Yousoof Ismail, M.; Mohd, S. What is the impact of ewom in social network sites on travel decision-making during the COVID-19 outbreak? A two-stage methodology. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 69, 101795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, F.; Sylvina, V.; Lestari, A. Toward New Normal: Bali Tourism Goes Extra Mile. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 704, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.K.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Velasco, K.E.; Abad, E.D.; Buencille, A.L.; Estorninos, E.M.; Cahigas, M.M.; Chuenyindee, T.; Persada, S.F.; Nadlifatin, R.; et al. Utilization of random forest classifier and artificial neural network for predicting the acceptance of reopening decommissioned nuclear power plant. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2022, 175, 109188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, Y.B.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Ong, A.K.; Nadlifatin, R.; Persada, S.F.; Chuenyindee, T.; Cahigas, M.M. Determining factors affecting preparedness beliefs among Filipinos on Taal Volcano eruption in Luzon, Philippines. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 76, 103035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayag, Y. How Easily Can Vaccinated People Spread COVID? The Atlantic. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2021/11/vaccinated-spread-the-coronavirus/620650/ (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Chen, S.; Fan, Y.; Cao, Y.; Khattak, A. Assessing the relative importance of factors influencing travel happiness. Travel Behav. Soc. 2019, 16, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 91 | 33.83% |

| Female | 178 | 66.17% | |

| Age | 15–24 | 214 | 79.55% |

| 25–34 | 17 | 6.32% | |

| 35–44 | 7 | 2.60% | |

| 45–54 | 25 | 9.29% | |

| ≥55 | 6 | 2.23% | |

| Occupation | Student | 196 | 72.86% |

| Employee | 47 | 17.47% | |

| Entrepreneurs | 24 | 8.92% | |

| Retired | 2 | 0.74% | |

| Budget/traveling expenses | <2 million IDR | 49 | 18.22% |

| 2–4 million IDR | 121 | 44.98% | |

| 4–6 million IDR | 62 | 23.05% | |

| 6–8 million IDR | 11 | 4.09% | |

| >8 million IDR | 26 | 9.67% | |

| Region | East Java | 131 | 48.69% |

| Central Java | 15 | 5.57% | |

| West Java | 14 | 5.20% | |

| Jakarta | 26 | 9.66% | |

| Bali & Nusa Tenggara | 22 | 8.17% | |

| South Sulawesi | 41 | 15.24% | |

| North Sumatera | 4 | 1.48% | |

| West Sumatera | 6 | 2.23% | |

| Maluku & Papua | 5 | 1.85% | |

| East Kalimantan | 5 | 1.85% | |

| Social Media Platforms | 3.39 | ||

| 3.28 | |||

| TikTok | 2.83 | ||

| YouTube | 2.62 | ||

| 2.36 | |||

| Travel Destination in Bali | Night life | 4.44 | |

| Mountain | 3.93 | ||

| Culture | 3.87 | ||

| Hidden gems | 3.61 | ||

| Café Aesthetic | 3.57 | ||

| Resort | 3.45 | ||

| Culinary | 3.08 | ||

| Beach | 3.00 |

| Latent Variables | Item | Measures | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | ATT1 | I think going traveling in the current situation is a fun and energizing choice | [25] |

| ATT2 | I think that traveling is all I want in the current situation | [26] | |

| ATT3 | I like to travel in the current situation | [27] | |

| ATT4 | I think it is delightful to travel in the current situation | [27] | |

| ATT5 | Given the current situation, I think that traveling is beneficial | [28] | |

| Hedonic Motivations | HM1 | I look for fun while traveling | [29] |

| HM2 | Traveling means a lot to me | [29] | |

| HM3 | I travel to fulfill my lifestyle | [30] | |

| HM4 | I go traveling to reward myself after a long day of working | [29] | |

| Subjective Norms | SN1 | People whose opinions I value support me to travel during the pandemic | [31] |

| SN2 | People whose important to me think it is okay to travel during the pandemic | [31] | |

| SN3 | I consider my friends’/colleagues opinion when deciding to travel in the current condition | [25] | |

| SN4 | Most people who are important to me agree that I should not be working too hard and go travel | [27] | |

| SN5 | People whose opinion I value would prefer that I spend my money on a positive activity | [27] | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | PBC1 | I have enough time to travel during the pandemic | [32] |

| PBC2 | I have enough budget to travel during the pandemic | [27] | |

| PBC3 | If I wanted to, I would go traveling rather than staying at home during the pandemic | [32] | |

| PBC4 | I feel there is nothing to prevent me from traveling in the current situation | [32] | |

| COVID-19 Safety Protocols | CSP1 | I tend to avoid the crowd on a trip during the COVID-19 | [32] |

| CSP2 | I tend to have discipline on using masks during my vacations | [33] | |

| CSP3 | I sanitize myself (by washing hands or using hand sanitizer) during the trip | [33] | |

| CSP4 | It is important to get fully vaccinated before going on a trip | [32] | |

| CSP5 | I feel safe traveling to a place that implements COVID-19 protocols | [32] | |

| CSP6 | I am concerned about prevention and hygiene issues during the trip | [29] | |

| Social Media Influence | SMI1 | I would like to travel because I want to experience new things and share them on social media | [34] |

| SMI2 | I tend to go to places that are viral on social media | [34] | |

| SMI3 | Social media plays a big part in my decision on traveling, such as where to stay or where to go | [34] | |

| SMI4 | Seeing someone go on a trip and post it on social media influenced me to travel | [34] | |

| Intention to Travel | INT1 | I want to go traveling as soon as possible | [25] |

| INT2 | I intended to travel for leisure | [25] | |

| INT3 | I am tempted to travel after seeing several travel promotion videos on social media | [34] | |

| INT4 | I am thinking of spending time with a different vibe somewhere | [32] | |

| INT5 | I would like to try and do something new for a short break | [29] |

| Latent Variables | Items | Factor Loadings | Cronbach’s α | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | ATT1 | 0.74 | 0.895 | 0.888 | 0.616 |

| ATT2 | 0.65 | ||||

| ATT3 | 0.86 | ||||

| ATT4 | 0.90 | ||||

| ATT5 | 0.75 | ||||

| Hedonic Motivation | HM1 | 0.58 | 0.731 | 0.763 | 0.449 |

| HM2 | 0.75 | ||||

| HM3 | 0.58 | ||||

| HM4 | 0.75 | ||||

| COVID-19 Safety Protocols | CSP1 | 0.44 | 0.806 | 0.819 | 0.436 |

| CSP2 | 0.62 | ||||

| CSP3 | 0.67 | ||||

| CSP4 | 0.77 | ||||

| CSP5 | 0.63 | ||||

| CSP6 | 0.77 | ||||

| Intention to Travel | INT1 | 0.71 | 0.769 | 0.798 | 0.457 |

| INT2 | 0.66 | ||||

| INT3 | 0.36 | ||||

| INT4 | 0.87 | ||||

| INT5 | 0.70 |

| Goodness of Fit Measures of SEM | Parameter Estimates | Minimum Cut-Off | Suggested by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incremental fit index (IFI) | 0.931 | >0.90 | [36] |

| Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) | 0.944 | >0.90 | [38] |

| Comparative fit index (CFI) | 0.938 | >0.90 | [36] |

| Goodness of fit index (GFI) | 0.897 | >0.80 | [39] |

| Adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) | 0.883 | >0.80 | [39] |

| Root mean square error (RMSEA) | 0.054 | <0.07 | [40] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cahigas, M.M.L.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Alexander, J.; Sutapa, P.L.; Wiratama, S.; Arvin, V.; Nadlifatin, R.; Persada, S.F. Factors Affecting Visiting Behavior to Bali during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10424. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610424

Cahigas MML, Prasetyo YT, Alexander J, Sutapa PL, Wiratama S, Arvin V, Nadlifatin R, Persada SF. Factors Affecting Visiting Behavior to Bali during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Approach. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10424. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610424

Chicago/Turabian StyleCahigas, Maela Madel L., Yogi Tri Prasetyo, James Alexander, Putu Lauterina Sutapa, Shannen Wiratama, Vincent Arvin, Reny Nadlifatin, and Satria Fadil Persada. 2022. "Factors Affecting Visiting Behavior to Bali during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Approach" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10424. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610424

APA StyleCahigas, M. M. L., Prasetyo, Y. T., Alexander, J., Sutapa, P. L., Wiratama, S., Arvin, V., Nadlifatin, R., & Persada, S. F. (2022). Factors Affecting Visiting Behavior to Bali during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Approach. Sustainability, 14(16), 10424. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610424