Sense of Place of Heritage Conservation Districts under the Tourist Gaze—Case of the Shichahai Heritage Conservation District

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Study Area

2.1. Tourist Gaze

2.2. Sense of Place

2.3. The Consensus Map

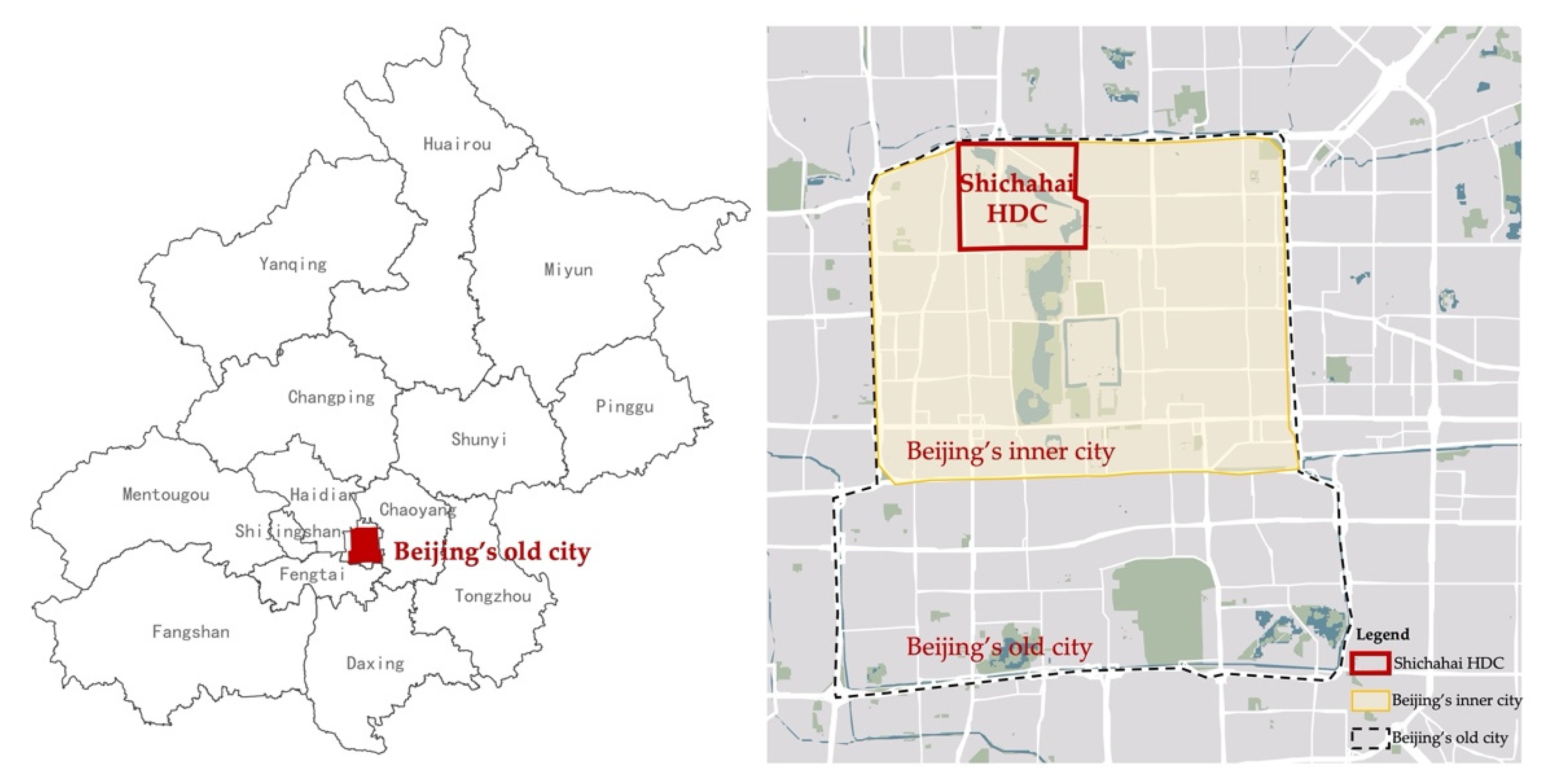

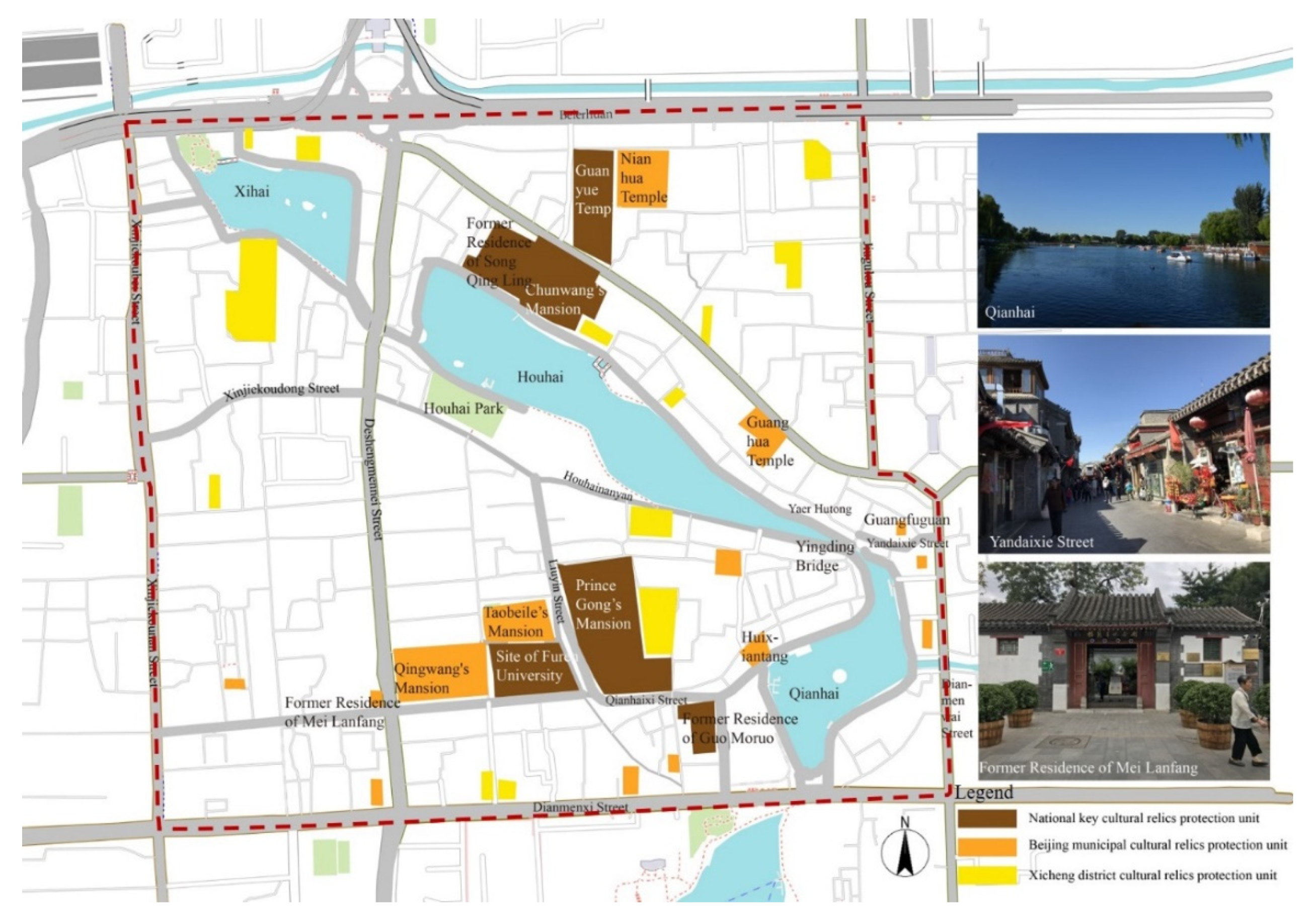

2.4. Study Area

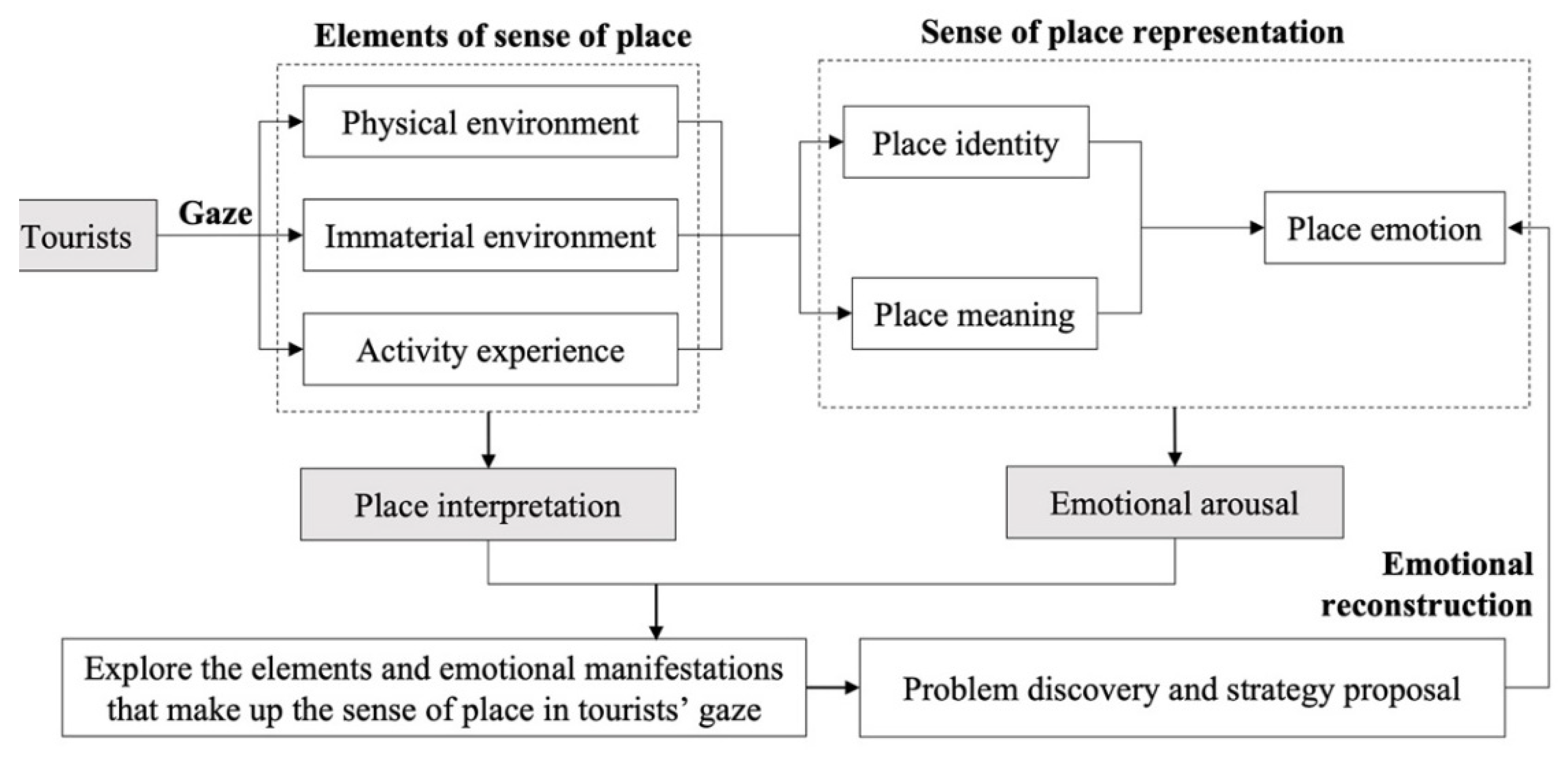

3. Methodology

3.1. Overall Research Framework

3.2. Snowball Sampling

3.3. Involvement Analysis

3.4. ZMET Analysis

3.4.1. Interview Preparation

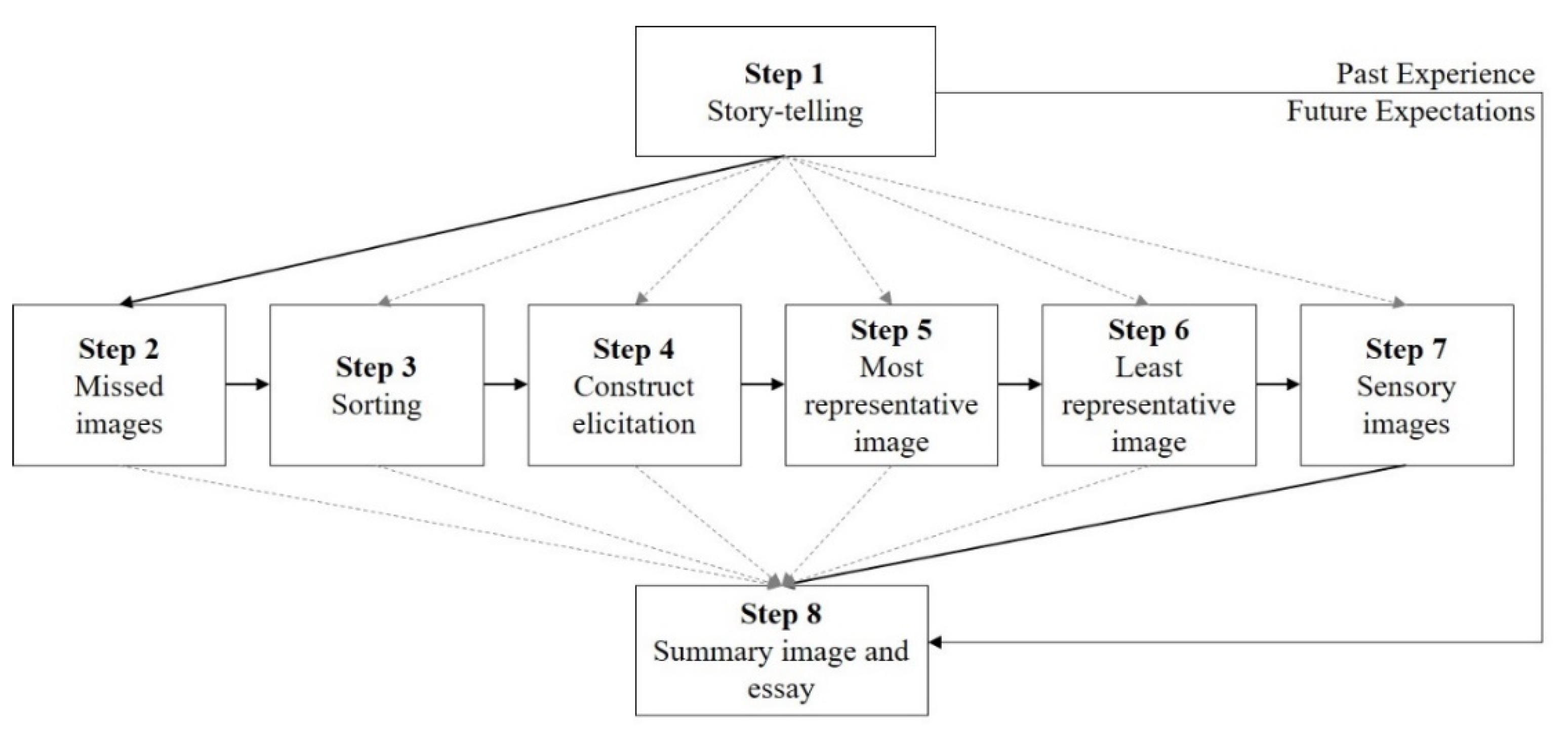

3.4.2. ZMET Interview

3.4.3. ZMET Interview Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sense of Place in the Shichahai HCD

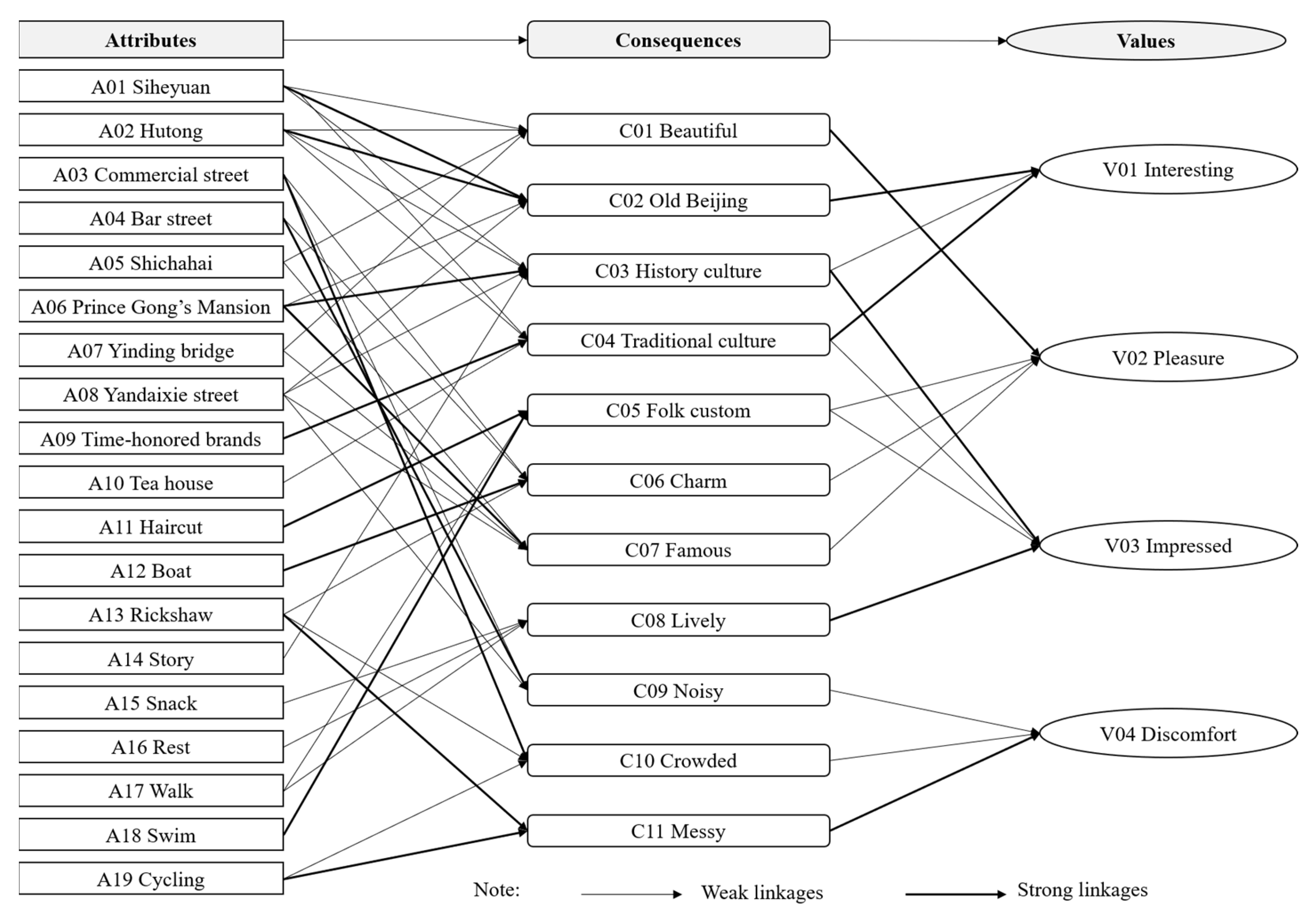

4.2. The Consensus Map of the Shichahai HCD

4.3. Elements of Sense of Place

4.3.1. Sense of Place in the Physical Environment

4.3.2. Sense of Place in an Immaterial Environment

4.3.3. Sense of Place in Experience Activities

4.3.4. Negative Sense of Place

4.4. Structural Models of Sense of Place

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niu, X.; Tian, C.; Sun, Z.; Huang, Q. An inquiry into the cultural DNA of space in Chinese cities. City Plan. Rev. 2020, 44, 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Xie, Y.; Wang, J. Gazed landscape and interactive landscape: The structural impacts of landscape types in tourism field on tourists’ senses of place. Tour. Trib. 2021, 36, 80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Li, H.; Cao, K. Value-oriented preservation and renovation of historic districts. Urban Dev. Stud. 2019, 26, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Rollo, J.; Jones, D.S.; Esteban, Y.; Tong, H.; Mu, Q. Towards Sustainable Heritage Tourism: A Space Syntax-Based Analysis Method to Improve Tourists’ Spatial Cognition in Chinese Historic Districts. Buildings 2020, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The State Council of the PRC. The Regulation on the Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities, Towns and Villages. 2018. Available online: https://www.mnr.gov.cn/zt/zh/gtkjgh/zcfg/flxzfg/202201/t20220110_2717101.html (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Zhang, S. Introduction to the Conservation of Historical Cities (Second Edition): A Holistic Approach to Cultural Heritage and Historical Environmental Protection; Tongji University Press: Shanghai, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Xue, D.; Huang, G. The Effects of Residents’ Sense of Place on Their Willingness to Support Urban Renewal: A Case Study of Century-Old East Street Renewal Project in Shaoguan, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoi, T. Applying the caption evaluation method to studies of visitors’ evaluation of historical districts. Tour. Manag. Res. Policies Pract. 2011, 32, 1061–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumowidagdo, A.; Ujang, N.; Rahadiyanti, M.; Ramli, N.A. Exploring the sense of place of traditional shopping streets through Instagram’s visual images and narratives. Open House Int. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad-Moradi, A.; Yazdanfar, S.A.; Norouzian-Maleki, S. Exploring the Sense of Place Components in Historic Districts: A Strategy for Urban Designers and Architects. Iran Univ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 30–43. Available online: http://ijaup.iust.ac.ir/article-1-523-en.html (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Gustafson, P. Meanings of place: Everyday experience and theoretical conceptualizations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Ji, L. Going somewhere or for someone? The Sense of Human Place Scale (SHPS) in Chinese rural tourism. Tour. Manag. 2022, 91, 104530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfani, G. Sense of place as an investigative method for the evaluation of participatory urban redevelopment. Cities 2020, 99, 102648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Fu, X. Gaze and tourist-host relationship–state of the art. Tour. Rev. 2020, 76, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Liang, B.; Pan, Z.; Lin, Y. Research on presentation of Shanghai historic blocks: Based on tourist gaze. Tour. Res. 2016, 8, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jarratt, D.; Phelan, C.; Wain, J.; Dale, S. Developing a sense of place toolkit: Identifying destination uniqueness. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, H.; Bian, L. Heritage Protection and Sustainable Development: Focusing on Listed Buildings in the UK, Japan and South Korea. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2019, 37, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, L.; Wu, Q.; Shi, Y. Discrimination and Thinking of the Conservation of Historic and Cultural Area in Beijing Old City. Beijing Plan. Rev. 2019, S2, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J.; Larsen, J. The Tourist Gaze 3.0; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Radley, A.; Taylor, D. Images of recovery: A photo-elicitation study on the hospital ward. Qual. Health Res. 2003, 13, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.L.; Feng, X. Residents’ sense of place, involvement, attitude, and support for tourism: A case study of Daming Palace, a Cultural World Heritage Site. Asian Geogr. 2020, 37, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganji, S.F.G.; Johnson, L.W.; Sadeghian, S. The effect of place image and place attachment on residents’ perceived value and support for tourism development. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.D.; Brown, G.; Kim, A.K.J. Measuring resident place attachment in a World Cultural Heritage tourism context: The case of Hoi An (Vietnam). Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2059–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijing Municipal Planning Commission. Conservation Plan for 25 Historical and Cultural Reserves in Beijing Old City; Beijing Yanshan Press: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, C. The value co-creation of residents and tourists in urban fringe communities from a tourism gaze perspective. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 36, 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Goulding, C. The museum environment and the visitor experience. Eur. J. Mark. 2000, 34, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarathunga, W.; Cheng, L. Tourist gaze and beyond: State of the art. Tour. Rev. 2020, 76, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstén, S.; Keskitalo, E.C.H. Feeling at home from a distance? How geographical distance and non-residency shape sense of place among private forest owners. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 32, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chapin, F.S., III; Knapp, C.N. Sense of place: A process for identifying and negotiating potentially contested visions of sustainability. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 53, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jepson, D.; Sharpley, R. More than sense of place? Exploring the emotional dimension of rural tourism experiences. J. Sustain. Tourism. 2014, 23, 1157–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion Limited: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, J. Picturing Bornholm: Producing and consuming a tourist place through picturing practices. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2006, 6, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogué, J.; de San-Eugenio-Vela, J. Geographies of affect: In search of the emotional dimension of place branding. Commun. Soc. 2018, 31, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Kyttä, M.; Stedman, R. Sense of place, fast and slow: The potential contributions of affordance theory to sense of place. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bott, S.; Cantrill, J.G.; Myers, O.E. Place and the Promise of Conservation Psychology. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2003, 10, 100–112. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24706959 (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Lin, C.F.; Fu, C.S. Cognitive implications of experiencing religious tourism: An integrated approach of means–end chain and social network theories. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Kang, M.; Yoon, S.; Kim, D. A consumer value analysis of mobile internet protocol television based on a means-end chain theory. Serv. Bus. 2014, 8, 587–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, S.S. Hierarchical value map of religious tourists visiting the Vatican City/Rome. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 21, 529–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Axhausen, K.W.; Wei, H.; Bian, L. Syntactical Morphological Histories Analysis on Top-Down Planned and Self-organised Street Networks of Old City Cores: The Case of Zurich Kreis 1 and Shichahai. Disp-Plan. Rev. 2021, 57, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Q. Research on the Complex Mechanism of Placeness, Sense of Place, and Satisfaction of Historical and Cultural Blocks in Beijing’s Old City Based on Structural Equation Model. Complexity 2021, 2021, 6673158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.N.; Li, Y.Q.; Liu, C.H.; Ruan, W.Q. A study on China’s time-honored catering brands: Achieving new inheritance of traditional brands. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaltman, G. How Customers Think: Essential Insights into the Mind of the Market; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ekici Cilkin, R.; Cizel, B. Tourist gazes through photographs. J. Vacat. Mark. 2022, 28, 188–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Wu, J.; Wei, L.; Cao, F.; Zhou, N. Typical Tourism Image Elements of Fenghuang Ancient Town Analyzed from the Tourist Gaze Perspective: Based on the Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique. Tour. Trib. 2018, 33, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mauri, C. What comes to mind when you think of sustainability? Qualitative research with ZMET. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2020, 12, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the involvement construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hitchcock, M.J. The Chinese female tourist gaze: A netnography of young women’s blogs on Macao. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. The personal involvement inventory: Reduction, revision, and application to advertising. J. Advert. 1994, 23, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D. Travel risks in the COVID-19 age: Using Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique (ZMET). Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Dong, J.; Zhang, Y.; He, Z.; Shi, L.; Cai, Y. A content analysis of e-cigarette related calls to the Shanghai health hotline, for the period 2014–2019. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2021, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Chao, W.H.; Lin, H.Y. Cultural inheritance of Hakka cuisine: A perspective from tourists’ experiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 7, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Pei, L.; Zhu, A.; Zhou, C.; Yin, C.; Li, S. Research on the driving mechanism of tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior in HCDs with environmental knowledge as moderating variable. Areal Res. Dev. 2021, 40, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

| Interviewees No | Gender | Gender | Country | RPII Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Woman | 20–29 | South Korea | 63 |

| P2 | Woman | 20–29 | China | 58 |

| P3 | Woman | 20–29 | China | 66 |

| P4 | Woman | 30–39 | China | 62 |

| P5 | Woman | 30–39 | China | 54 |

| P6 | Man | 20–29 | China | 58 |

| P7 | Man | 20–29 | China | 60 |

| P8 | Man | 40–49 | South Korea | 59 |

| P9 | Woman | 20–29 | China | 53 |

| P10 | Man | 30–39 | China | 58 |

| P11 | Woman | 20–29 | China | 58 |

| P12 | Woman | 50–59 | South Korea | 60 |

| P13 | Woman | 20–29 | China | 61 |

| P14 | Man | 30–39 | South Korea | 68 |

| P15 | Man | 20–29 | China | 61 |

| P16 | Woman | 30–39 | China | 57 |

| P17 | Woman | 30–39 | China | 68 |

| P18 | Man | 30–39 | South Korea | 68 |

| Main Category | High-Frequency Constructs |

|---|---|

| Physical environment (26) |

|

| Immaterial environment (5) | Stories, rickshaws, tea houses, haircuts, time-honored brands |

| Activity experience (9) | rest, bike ride, walk, sit, swim, visit, play, chat |

| Place attachment (26) | Enjoyable, pleasant, lively, cluttered, crowded, noisy, harmonious, style, history culture, old Beijing, folk custom, traditional culture, rich, charming, famous, discordant, dilapidated, narrow, ruined, insufficient, interesting, good, impressive, poor |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, H.; Zhou, M.; Kang, S.; Zhang, J. Sense of Place of Heritage Conservation Districts under the Tourist Gaze—Case of the Shichahai Heritage Conservation District. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610384

Wei H, Zhou M, Kang S, Zhang J. Sense of Place of Heritage Conservation Districts under the Tourist Gaze—Case of the Shichahai Heritage Conservation District. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610384

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Hanbin, Mengru Zhou, Sunju Kang, and Jiahao Zhang. 2022. "Sense of Place of Heritage Conservation Districts under the Tourist Gaze—Case of the Shichahai Heritage Conservation District" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610384

APA StyleWei, H., Zhou, M., Kang, S., & Zhang, J. (2022). Sense of Place of Heritage Conservation Districts under the Tourist Gaze—Case of the Shichahai Heritage Conservation District. Sustainability, 14(16), 10384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610384