Linking Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Well-Being—A Eudaimonia Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Corpoorate Social Responsibility

2.2. Employee Perception of CSR

2.3. Eudaimonic Well-Being at Work

“between those needs (desires) that are only subjectively felt and whose satisfaction leads to momentary pleasure, and those needs that are rooted in human nature and whose realization is conducive to human growth and produces eudaimonia, i.e., “well-being.” In other words […] the distinction between purely subjectively felt needs and objectively valid needs—part of the former being harmful to human growth and the latter being in accordance with the requirements of human nature”

- -

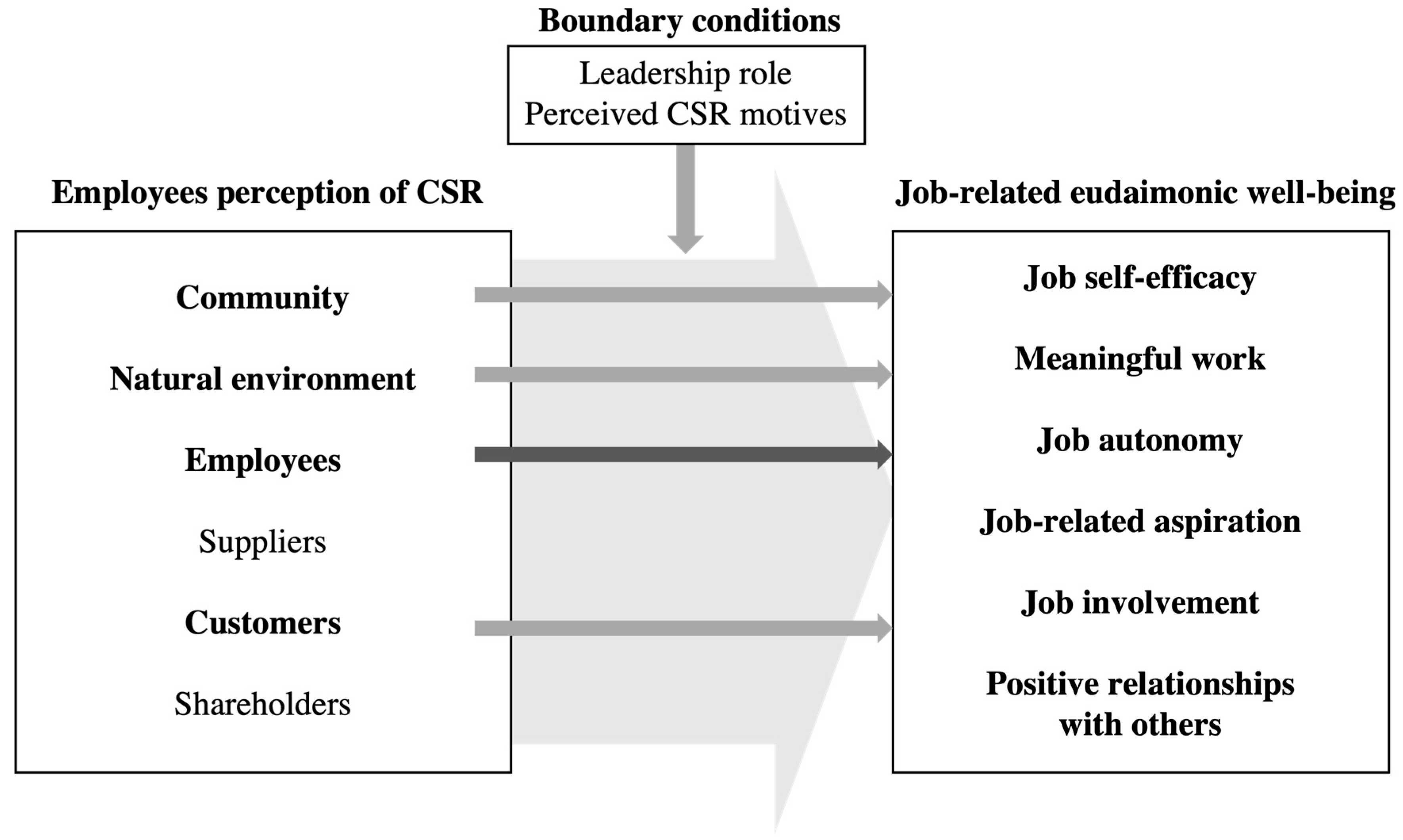

- How does employees’ perceptions of CSR influence their job-related eudaimonic well-being?

- -

- How can job-related eudaimonic well-being be conceptualized?

3. Research Method

3.1. Sample

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Findings on Employee Perceptions of CSR

4.1.1. Community

“Then of course you have the indirect stakeholders, who you only have to deal with if something really bad happens, like the police or authorities. Of course, you want to avoid that. Nevertheless, you have to take that into account. For me, that simply means being prepared and, above all, knowing how to communicate that in the event of a certain situation […], how to deal with the authorities, in the event of an accident or major event, or how to deal with the media.”(IB, 1)

4.1.2. Natural Environment

“The environment or society as a whole—I use that relatively closely—is very important to me. I would never work for an employer who, in my view, was unethical there or really only had their financial gain in mind.”(IG, 1)

“[…] the environment, which is very important for the management of the company, that they use resources as sustainably as possible, that they invest for a longer horizon.”(IE, 1)

“I think the environment is important because it is our future. […] But if I’m completely honest, the focus is ultimately… social responsibility is not just the environment, it’s also the social and financial aspects. At the end of the day, you also want your business to be financially stable. I think many companies would already have a paper in their drawer that they could pull out and do more sustainability if the demand was greater. […] But I think a lot of it is what guests are asking for. And the concept absolutely resonates with the guests. If the guest didn’t want it, I don’t know if one would do it then, because ultimately you have to sell the hotel rooms and the experience and be profitable. I wouldn’t subscribe to it now that it’s just for the environment… It’s just holistic. Certainly it’s important, also the issues of reducing plastic, reducing single-use plastic. These are all projects that the company values. And because it’s such an important point of sale with the whole farm-to-table, it’s already something that the company is pushing. I’m not saying that the main focus is out of goodwill for the environment. But it’s initiatives that benefit the environment.”(IH, 1)

4.1.3. Employees

“Above all, our own employees, whether it’s always looking for conversations, one to one, always making the rounds, always having a coffee or tea with one or the other, because that’s where you find out most things instead of in official meetings or something. That’s the most important thing, because it’s about the health and safety of the employees. It’s also a personal issue.”(IB, 2)

“With employees, it’s that we want to work with them for a long time. We want to have a long relationship. We are also very active in development, so that people have opportunities for advancement, can develop—that’s important—and also feel good.”(ID, 1)

“Then also that transparent communication takes place on a regular basis: ‘Where are we right now?’ This is called Leadership Day.”(II, 1)

“[…] He involves the employees from A to Z, asks for their opinions, always keeps them up to date, shows them in which phase we are, […] Basically, the employees could really have a lot of say.”(IB, 3)

“Since I’ve been here, actually, they’ve constantly been expanding the range of courses and training opportunities, where employees can develop their technical skills, but also their soft skills, but also something that is perhaps outside the field of activity, that brings the out-of-the-box mindset, and also that they organize talks.”(II, 2)

“[Our boss] puts a lot of emphasis on working sustainably, so it’s not that you work 80 h a week and then you’re completely exhausted […] for the rest of the month, but that we take our time and that we have a healthy work-life balance.”(IA, 1)

4.1.4. Suppliers

“I think, first of all, we have to communicate well with them [the suppliers], and secondly, it’s important to give them freedom in that sense. For example, they all have a key to our premises. We have trust in the people who deliver, even when we’re not there. If we ever have something, if something is burning, […] they would be willing to come then. It’s not like they just say, ‘No, now you haven’t ordered. We’re not coming.’ […] They were also selected according to that. […] They are actually companies that the business owners, that is [owner of the catering, wine trade and vinery company] himself, knows and values that you get along well with them.”(IF, 1)

“We also place value on having good relationships with our suppliers. We also do a lot there and have very long-standing relationships.”(ID, 2)

4.1.5. Customers

“That you make that transparently available [..] to the consumers, the customers, regardless of whether it leaves a good image of the product or not. I believe that [name of production plant of a retail company] is very, very strongly committed to this.”(IG, 2)

4.1.6. Shareholders

“The hotels are owned by the [owners of the hospitality industry group] family, which runs [hospitality industry group]. The ownership is important here, as they obviously hold the majority and have the say, and a lot comes from them.”(IE, 2)

4.2. Findings on Job-Related Eudaimonic Well-Being

4.2.1. Job Self-Efficacy

“I think it’s always more pleasant when you’re convinced of the approach, procedure, or whatever is under discussion that one chooses. […] I have opportunities to discuss it with someone from the team. […] a colleague with whom I’m personally on great terms, where I know they’re familiar with the topic and perhaps have more experience. But it can also be the boss. […] and then ask: ‘Hey, can I tell you about my situation? Can I tell you what my thoughts are? Can you ask yourself questions that come to mind or that come up for you when I tell you this?’ And then getting new clues or new ideas through a discussion that I feel more comfortable with, and depending on that, also a confirmation, if it’s a confirmation, or if it’s not a confirmation, but a new approach or a different view. […] I had a blind spot there, now I’ve shed new light on it, and I can decide on a better or broader, more supported basis on how to proceed.”(IG, 3)

“I always prepare myself very well for all possible scenarios that could come up. Particularly in the case of presentations to management, I really think about the most critical questions that might come up right from the start, and then I feel confident when I have an answer to everything that I can then go into the shark tank, so to speak. Most of the time then it’s not as bad as I’d made it out to be. You assume the worst and then you’re actually prepared for everything and then it’s not bad at all.”(II, 3)

“That’s also the kick I need, that not everything is always one hundred percent clear and I don’t always move in the comfort zone. That’s the only way I can move forward and grow.”(II, 4)

4.2.2. Meaningful Work

“That’s actually what drives me. […] I like to get up every morning because I like doing what I do and I also see the meaning behind it and the result is also really enjoyable. But even there: It’s not always fun, that’s clear. But on the whole, the activity and the goals in the field in which we operate are what drive us.”(IC, 1)

“Definitely a meaningful activity and also the freedom, creative freedom, where I realize that I can make a difference myself, and not that I’m just a cog or a set screw in a giant organization, and no one cares what I do or don’t do, but that I’m really listened to and taken seriously, that I’m allowed to contribute and that I’m wanted.”(II, 5)

“To get appreciation, that is, gratitude, but also mindfulness that others see what is being done.”(ID, 3)

“For me it’s very important because when I’m happy here and—I have children, I have a husband at home—when things are going well here and I’m happy, then I also radiate that to my children. I think it’s very important that they also see that mommy is happy and that everyday life is going the way I wanted it to, even if not everything is always perfect in the restaurant business.”(IF, 2)

4.2.3. Job Autonomy

“We have a great deal of freedom in that respect. It has always been the case that we can decide for ourselves how to approach things. Of course there are encounters with the boss where we can ask questions if we have them. Relatively rarely there are also such things where he then asks what the current status is, how to proceed, etc., but hardly ever. What I do to get where I want to go is really completely up to me. That is certainly something that is very, very cool.”(IG, 4)

“And for me, it’s important that he gives me that responsibility and that trust.”(IF, 3)

“Very important. And I have to say that here, especially in our department, in our situation, it’s even more than expected. […] You have to decide for yourself, do things yourself, and you’re allowed to work autonomously, and you have enough to do. But ultimately… It’s better that way than the other way around, when you have the feeling that you have someone constantly watching over your shoulder and have to ask about every sentence you write or every phone call you make, how, where, and what. That would tend to slow you down and annoy you, I think.”(IE, 3)

“Yes, I have the feeling that you don’t have to be completely free. […] a little less freedom would still be nice at work.”(IA, 2)

4.2.4. Job-Related Aspiration

“Yes, very important, because otherwise it gets boring. If it’s not a challenge, you don’t learn anything. You should also grow from it and afterwards, when you have found a solution, it is all the more beautiful. […] You can never please everyone, but at least you can find a way that everyone can live with. That makes it exciting, very varied.”(II, 6)

“I’m a bit torn on that one. I think that for me as an employee, an environment in which I feel comfortable and also a bit safe is a prerequisite or certainly important, but there must always be challenges, because otherwise it gets too boring. In other words, there must always be change. But I also believe that if it’s not on a basis where you feel good and a bit comfortable, that it can also become too stressful at some point, too many new things at once or so.”(IG, 5)

4.2.5. Job Involvement

“To also have a job that is enjoyable. The restaurant business is tough, but you can work in beautiful surroundings, and you work in a place where people come and actually have a good time. It’s an emotional business, and you either like it or you don’t, and if you like it, you do it with passion. That’s the point for me.”(IC, 2)

“I find it very cool that I was given the opportunity and was supported, even as a young woman, that I was promoted, and also accepted one hundred percent. Opinions are sought everywhere. I think our work is appreciated. That’s at least the feedback or my perception of what I’m picking up. I am taken very seriously. So I feel very accepted. It is really very nice.”(II, 7)

“If I don’t feel comfortable there and if I notice it doesn’t fit or I have different values than the company, or we’re not moving in the same direction, then it would be a reason for me to feel that I am in the wrong place. That’s why it’s very important for me, and also that I notice the acceptance from them, that they take me seriously and notice that the cooperation works.”(II, 8)

4.2.6. Positive Relationships with Others

“I think the most important thing for me is my colleagues, including my boss, that I get along well with them. I don’t think it would matter what the work content is if I couldn’t meet people privately or somehow say, when we somehow have a drink together, cool, I’m happy to spend time with them. Then the work content could still be as cool, exciting, and varied as can be, I think that would force me to change jobs in the medium term, for myself. That is certainly important.”(IG, 6)

“To offer a good environment there, now also in these times, to be close to the employees despite the size, also to maintain personal contact.”(ID, 4)

“You have to feel that there is a willingness of the employees, but also of their superiors, to push your activity and your projects.”(IB, 4)

4.3. Findings on the Link between Employee Perceptions of CSR and Job-Related Eudaimonic Well-Being

“Nowadays there has been a shift that you don’t just work to earn money, but to have fulfilment or to feel good. That’s why I think it’s important that the place where you work offers something and also tries to do something good for the stakeholders, such as employees and students, and also tries to do something good in general.”(IA, 3)

“Yes, I think there is certainly a stronger identification with the company if I have the feeling that the employer is mindful of their stakeholders. I would take out owner as a stakeholder, if it were a stock corporation, which it is not in our case. I don’t think that would give me much. But the overall impression, [production plant of a retail company] doesn’t want to simply squeeze money out of the customers and get the highest possible price for some product, but the feeling, yes, it does want to produce the best value for money for the customer […] or make a commitment in terms of sustainability, where perhaps it’s above what one would have to, certainly helps that I identify very strongly with the employer. It certainly depends on what stakeholder engagement. I can’t imagine working for a company that simply exploits its employees.”(IG, 7)

“If you look strictly at why you get up in the morning, I think social sustainability is the most important point, that the company treats both its employees and the people around it decently and maintains good relationships, and doesn’t try to exploit everything, let’s say, to the max. When you read about companies like this, you get the feeling that everything is trimmed for financial success, whatever the cost. I think that’s a very important aspect of working for a company, that it’s not some kind of exploitation.”(IH, 2)

“One thing is that you’re valued, but also I think it’s important that the company looks at the employees as one of the most important stakeholders of the company, because ultimately they’re the ones who do the work and look to make sure the guests are doing well.”(IH, 3)

“It’s clear that if I have any responsibilities, I’ll take care of them first, but I’m pretty free to say: I’ll go to the gym first, or now I’ll take a break or something else, or I can say that I’ll stay at home for a day. Remote working is also okay if you want to be by yourself or switch off a bit. […] So that it is relatively or as pleasant as possible for us to work, because ultimately it is good for us, but also for him [the boss] in terms of sustainability.”(IA, 4)

“There are things that I look at purely financially, such as the pension fund. There, at the end of the day, it’s simply a salary component that is not paid out today, but it will be in the future. If I were to work somewhere else, it could simply be compensated through my salary. It doesn’t really matter to me in that sense. The other thing, the further training, for example, is certainly important, that it remains exciting for me, that I can learn something new. I think I would get bored pretty quickly if I did the same thing day after day for years. That with the learning there is always a change in the work content, that when I have done the French course, for example, I can also do or give projects or training in French. That is certainly also important for long-term happiness for me as an employee.”(IG, 8)

“One example is, during COVID, during the first lockdown, it was so bad in Italy. Of course, we have many employees in Ticino from Italy who came across the border. Some of them couldn’t go home during that time. Then [retail company] booked hotels for them and they were in hotels there for weeks. We have an internal platform, an intranet, where they can also post pictures, it’s called ‘Insta-[retail company]’. They then had dinner together, and how the other stores reacted: ‘I am [retail company]. We stick together. We’re a family.’ And you actually get that feeling.”(II, 9)

4.3.1. Boundary Condition: Leadership Role

“If I believe in what we do, then I can identify with it well. Then I’m also proud to tell people what I do and where I work. That often also has to do with the top, what is exemplified by ownership or management. It may not get to the bottom, but if it’s not working at the top, then it’s certainly very difficult. If you realize from the top that you have ownership or management that is just as passionate about it and drives that, then you can go along faster, because otherwise you’re constantly in a clash.”(IH, 4)

4.3.2. Boundary Condition: Perceived Motives for CSR

“To be honest: It is still far from enough to cover the entire quantity that one would have to cover from our own production. […] That is of course interesting to use [for marketing] and nice for the guests to see that it comes from there [local production site], but yes… For the marketing you can use that nicely, but it is just not the whole truth.”(IE, 4)

“That you have the feeling, even in the media and in marketing, that free journalism or that people write freely about something, that almost doesn’t exist. You get the feeling that it’s all barter deal-like—you do this, for that I’ll do that—so sometimes you think you’re almost obligated. You can’t say anything bad. You help each other, but at the end of the day, you don’t know if it’s of any use, if it’s authentic, if anyone even reads it; does it still have any value?”(IE, 5)

“In general, also for sustainability, not from the consumer’s point of view, but really as a company, we also have very ambitious goals, that we will be CO2-neutral by 2030 […], and by 2050 the entire circular economy, that it really takes on a pioneering role there. That it is not, in my view, just doing this for greenwashing, i.e., for marketing reasons, but really because it has an interest and sees itself as having a responsibility to society or the environment in general.”(IG, 9)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Structure | Questions |

|---|---|

| Welcome and introduction |

|

| Thematic block I: CSR |

|

| Thematic block II: Job-related eudaimonic well-being |

|

| Closing questions |

|

| End |

|

References

- Davies, R. The business community: Social responsibility and corporate values. In Making Globalization Good: The Moral Challenges of Global Capitalism; Dunning, J.H., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 301–319. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, H. Organizational responsibility: Doing good and doing well. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Zedeck, S., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 855–879. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Ganapathi, J.; Aguilera, R.V.; Williams, C.A. Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, S.; Fleischman, G. Ethics programs, perceived corporate social responsibility and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 77, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J.; Porter, C.O.L.H.; Ng, K.Y. Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. On corporate social responsibility, sensemaking, and the search for meaningfulness through work. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1057–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Kelley, K. The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Bus. Ethics Q. 2014, 24, 165–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G.; Rockmann, K.W.; Kaufmann, J.B. Constructing professional identity: The role of work and identity learning cycles in the customization of identity among medical residents. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Work Redesign; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, K.A.; Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Kelloway, E.K.; McKee, M.C. Transformational leadership and psychological well-being: The mediating role of meaningful work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoop, R. Relieving stress through value-rich work. J. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 134, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, L.; Logsdon, J.M. How corporate social responsibility pays off. Long Range Plann. 1996, 29, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Snider, J.; Hill, R.P.; Martin, D. Corporate social responsibility in the 21st century: A view from the world’s most successful firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 48, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J.B.; Sundgren, A.; Schneeweis, T. Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1988, 31, 854–872. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D.J. Measuring corporate social performance: A review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 50–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante Boadi, E.; He, Z.; Bosompem, J.; Opata, C.N.; Boadi, E.K. Employees’ perception of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its effects on internal outcomes. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 611–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Benson, J. When CSR is a social norm: How socially responsible human resource management affects employee work behavior. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1723–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demasi, R. Bridging CSR and individual well- and ill-being: A review and research agenda. In Proceedings of the 82nd Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Seattle, WA, USA, 5–9 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.L.; Woo, E.; Uysal, M.; Kwon, N. The effects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on employee well-being in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1584–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Yu, G.B.; Sirgy, M.J.; Singhapakdi, A.; Lucianetti, L. The effects of explicit and implicit ethics institutionalization on employee life satisfaction and happiness: The mediating effects of employee experiences in work life and moderating effects of work–family life conflict. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 855–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, O.; Islam, J.U. Effect of CSR activities on meaningfulness, compassion, and employee engagement: A sense-making theoretical approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Milstein, M.B. Creating sustainable value. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2003, 17, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3BL Media. Available online: https://100best.3blmedia.com/?_ga=2.169228705.1678247714.1657107830-1350948927.1657107830 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Waddock, S.A.; Bodwell, C.; Graves, S.B. Responsibility: The new business imperative. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2002, 16, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L. Stakeholders influence capacity and the variability of financial returns to corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 794–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosse, D.A.; Phillips, R.A.; Harrison, J.S. Stakeholders, reciprocity, and firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Benjamin, J.D. Corporate social performance and firm risk: A meta-analytic review. Bus. Soc. 2001, 40, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, C.W.; Skitka, L.J. Corporate social responsibility as a source of employee satisfaction. Res. Organ. Behav. 2012, 32, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, S.B.; Waddock, S.A. Institutional owners and corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 1034–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, N.A.; Aboobaker, N.; Edward, M. Corporate social responsibility and organizational commitment: Effects of CSR attitude, organizational trust and identification. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2020, 15, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, E.G.; Foulon, M.; Handfield-Jones, H.; Hankin, S.M.; Michaels, E.G., III. The war for talent. McKinsey Q. 1998, 3, 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research and Application; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J. Competitive Advantage through People; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Riordan, C.M.; Gatewood, R.D.; Bill, J.B. Corporate image: Employee reactions and implications for managing corporate social performance. J. Bus. Ethics 1997, 16, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Akremi, A.; Gond, J.-P.; Swaen, V.; De Roeck, K.; Igalens, J. How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. J. Manag. 2015, 44, 619–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Yam, K.C.; Aguinis, H. Employee perceptions of corporate social responsibility: Effects on pride, embeddedness, and turnover. Pers. Psychol. 2019, 72, 107–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Shao, R.; Thornton, M.A.; Skarlicki, D.P. Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 895–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Safieddine, A.M.; Rabbath, M. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility synergies and interrelationships. Corp. Gov. 2008, 16, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, T.K.; Carapinha, R.; Pitt-Catsouphes, M.; Valcour, M.; Lobel, S. Corporate social responsibility and employee outcomes: The role of country context. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2017, 26, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.P.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Godwin, L.N. Is the perception of ‘goodness’ good enough? Exploring the relationship between perceived corporate social responsibility and employee organizational identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E. An employee-centered model of organizational justice and social responsibility. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 1, 72–94. [Google Scholar]

- De Roeck, K.; Delobbe, N. Do environmental CSR initiatives serve organizations’ legitimacy in the oil industry? Exploring employees’ reactions through organizational identification theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Post, J.E.; Preston, L.E.; Sachs, S. Managing the extended enterprise: The new stakeholder view. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2002, 45, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E.R. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, H.C.; Boo, E.H.Y. The link between organizational ethics and job satisfaction: A study of managers in Singapore. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 29, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.K. The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Bus. Soc. 2004, 43, 269–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Panagopoulos, N.G.; Rapp, A. Employee judgments of and behaviors towards corporate social responsibility: A multi-study investigation of direct, cascading, and moderating effects. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 990–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, K.; Hattrup, K.; Spiess, S.-O.O.; Lin-Hi, N. The effects of corporate social responsibility on employees’ affective commitment: A cross-cultural investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1186–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavin, J.F.; Maynard, W.S. Perceptions of corporate social responsibility. Pers. Psychol. 1975, 28, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnahan, S.; Kryscynski, D.; Olson, D. How Corporate Social Responsibility Reduces Employee Turnover. In Proceedings of the Academy of Management, Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 7 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jamali, D.; Samara, G.; Zollo, L.; Ciappei, C. Is internal CSR really less impactful in individualist and masculine cultures? A multilevel approach. Manag. Decis. 2019, 58, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A. Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Greening, D.W. Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 40, 658–672. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.M. The significance of task significance: Job performance effects, relational mechanisms, and boundary conditions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabner-Kräuter, S.; Breitenecker, R.J.; Tafolli, F. Exploring the relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and intention to emigrate: Evidence from a developing country. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 51, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Symposium on Amartya Sen’s philosophy: 5 adaptive preferences and women’s options. Econ. Philos. 2001, 17, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Capability and well-being. In The Quality of Life; Nussbaum, M.C., Sen, A., Eds.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1993; pp. 30–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Berntson, G.G. The affect system: Architecture and operating characteristics. Curr. Dir. Psychol. 1999, 8, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, E. Primary and secondary process in waking and in altered states of consciousness. Acad. Psychol. Bull. 1982, 3, 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, A.S.; Schwartz, S.J.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Ravert, R.D.; Williams, M.K.; Bede Agocha, V.; Yeong Kim, S.; Brent Donnellan, M. The questionnaire for eudaimonic well-being: Psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. J. Posit. Psychol. 2010, 5, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B. The contours of positive human health. Psychol. Inq. 1998, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.D. Happiness at work. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 384–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. A conceptual framework for the study of work and mental health. Work Stress 1994, 8, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozeman, D.P.; Perrewe, P.L.; Hochwarter, W.A.; Brymer, R.A. Organizational politics, perceived control, and work outcomes: Boundary conditions on the effects of politics. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbers, R.; Loughlin, C.; Zweig, D. Young workers’ job self-efficacy and affect: Pathways to health and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 67, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Development of the job diagnostic survey. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Horn, J.E.; Taris, T.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Schreurs, P.J. The structure of occupational well-being: A study among Dutch teachers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodahl, T.M.; Keyner, M. The definition and measurement of job involvment. J. Appl. Psychol. 1965, 49, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bono, J.E.; Judge, T.A. Self-concordance at work: Toward understanding the motivational effects of transformational leaders. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 554–571. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hopf, C. Qualitative Interviews: Ein Überblick. In Qualitative Forschung: Ein Handbuch; Flick, U., von Kardorff, E., Steinke, I., Eds.; Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag: Reinbek bei Hamburg, Germany, 2017; pp. 349–360. [Google Scholar]

- Meuser, M.; Nagel, U. Experteninterviews–vielfach erprobt, wenig bedacht: Ein Beitrag zur qualitativen Methodendiskussion. In Qualitativ-Empirische Sozialforschung; Garz, D., Kraimer, K., Eds.; Westdeutscher Verlag: Opladen, Germany, 1989; pp. 441–471. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B.L.; De Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory—The State of the Art; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Social well-being. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1998, 61, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.A. Understanding and validity in qualitative research. In The Qualitative Researcher’s Companion; Huberman, A.M., Miles, M.B., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1992; pp. 37–64. [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo, R.F.; Colquitt, J.A. Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator of Job-Related Eudaimonic Well-Being | Definition |

|---|---|

| Job self-efficacy | Extent to which one perceives to be able to perform well in one’s job [78,79] |

| Meaningful work | “[W]ork experienced as particularly significant and holding more positive meaning for individuals” [10] (p. 95) |

| Job autonomy | Job characterized by “substantial freedom, independence, and discretion to the employee in scheduling the work and in determining the procedures to be used in carrying it out” [80] (p. 162) |

| Job-related aspiration | “Degree to which a person pursues challenging goals in the job” [81] (p. 367) |

| Job involvement | “[T]he degree to which a person is identified psychologically with his work, or the importance of work in his total self-image” [82] (p. 24) |

| Positive relations with others | Having warm and trusting interpersonal relationships with others [83] |

| Abbreviations | Type of Organization | Function | Interview Date and Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| IA | University | Research assistant | 24 May 2022, in person |

| IB | Pharmaceutical company | Environment, Health, and Safety Specialist | 30 May 2022, by video call |

| IC | Catering, wine trade, and vinery company | General manager innovation and catering projects | 3 June 2022, by video call |

| ID | Catering, wine trade, and vinery company | General manager HR | 3 June 2022, by video call |

| IE | Hospitality industry group | Marketing Coordinator | 8 June 2022, in person |

| IF | Catering, wine trade, and vinery company | Restaurant manager | 8 June 2022, in person |

| IG | Production plant of a retail company | Senior lean coach | 8 June 2022, by video call |

| IH | Hospitality industry group | Director of Finance and Accounting | 15 June 2022, in person |

| II | Retail company | Head of Omnichannel Retailing | 17 June 2022, by video call |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bauer, E.L. Linking Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Well-Being—A Eudaimonia Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10240. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610240

Bauer EL. Linking Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Well-Being—A Eudaimonia Perspective. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10240. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610240

Chicago/Turabian StyleBauer, Emily Luisa. 2022. "Linking Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Well-Being—A Eudaimonia Perspective" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10240. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610240

APA StyleBauer, E. L. (2022). Linking Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Well-Being—A Eudaimonia Perspective. Sustainability, 14(16), 10240. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610240