Green Taxes in Africa: Opportunities and Challenges for Environmental Protection, Sustainability, and the Attainment of Sustainable Development Goals

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

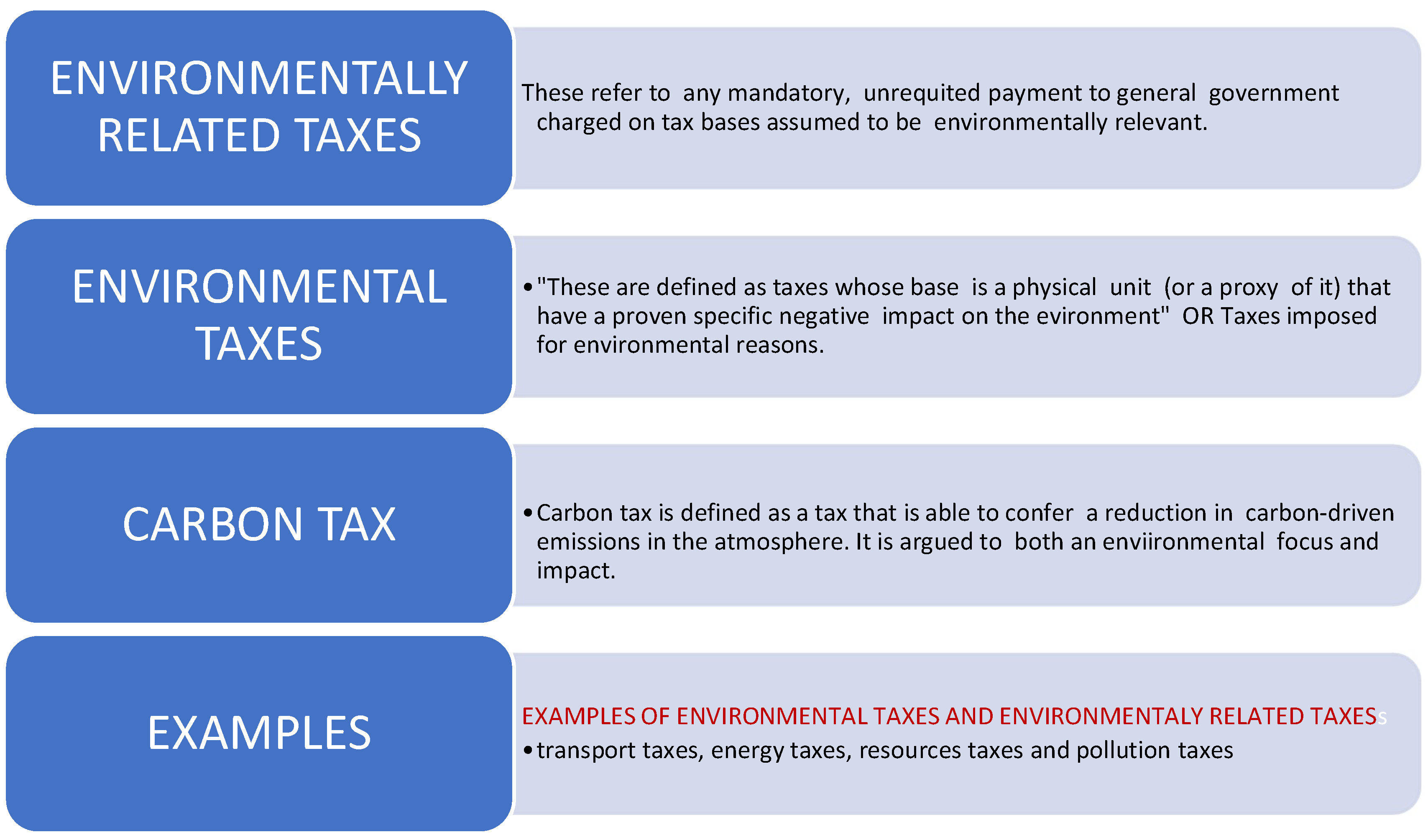

2.1. Definition of Green Taxes

Principles Guiding Environmental Taxes

2.2. Theoretical Framework Guiding the Review

2.2.1. The Double Dividend Theory or Hypothesis

Evaluative Discussion of the Double Dividend Theory

Existing Taxes and the DD Theory

Employment or Labor and the DD Theory

The Tax Burden and the DD Theory

2.3. Green/Environmental Taxation in African Countries

2.4. Types of Green/Environmental Taxes Levied by African Counties/Strategies of Levying Green Taxes

2.5. Motives for Levying Green Taxes/Environmental Taxes in African Countries

- (1)

- Environmentally protection and sustainability

- (2)

- Revenue mobilization

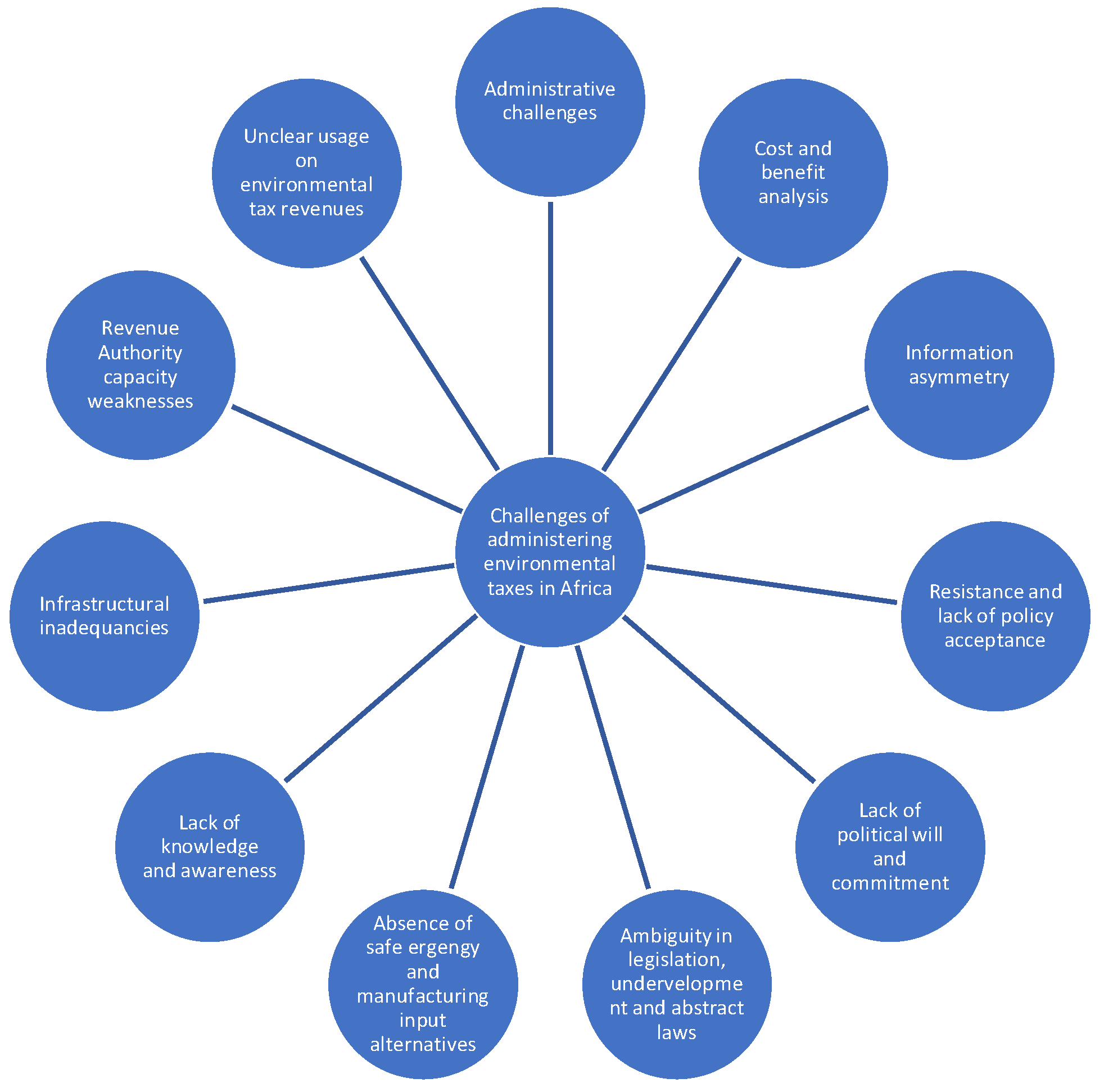

2.6. Challenges of Levying Green Taxes in Africa

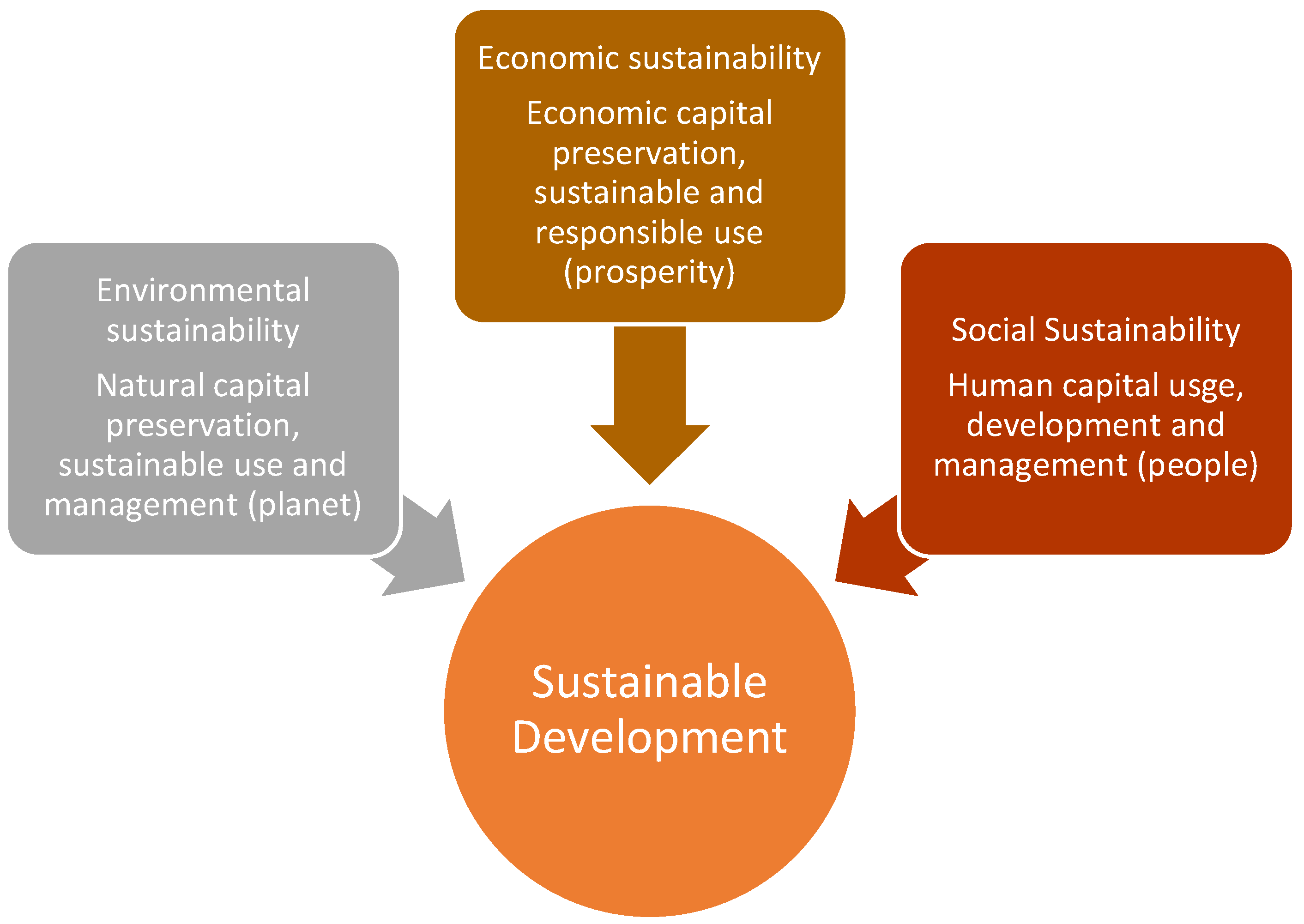

2.7. Green Taxes, Environmental Sustainability and Protection, Revenue Mobilization and Sustainable Development

“Determined to protect the planet from degradation, including through sustainable consumption and production, sustainably managing its natural resources and take urgent action on climate change, so that it can support the needs of the present and future generations”.

2.7.1. Sustainability, Environmental Sustainability and Protection

2.7.2. Sustainable Development

3. Materials and Methods

4. Discussion of Findings

4.1. Green Taxes in Africa Countries

4.2. Motives for Levying Green Taxes in Africa

4.3. Environmental Sustainability and Protection, Revenue Generation and Sustainable Development Implications of Levying of Green Taxes

4.3.1. Revenue Generation

4.3.2. Incentive Effect of Green Taxes

4.3.3. Correction of Market Failures or Externalities

4.3.4. Achievement of Environmental Objectives

4.3.5. Ease of Administration

4.3.6. Addressing the Impact of Environmental Damage or Climate Change

4.3.7. Encouraging Innovation

4.3.8. Contribute to Effective and Fair Distribution of Income and Welfare

4.3.9. Avail an Opportunity to Take Advantage of Multiple Environmental Gains

4.3.10. Increasing Inequality and the Vulnerability of Low-Income Earners

4.3.11. Competitiveness

5. Conclusions, Limitations, Areas of Further Research and Recommendations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kluza, K.; Ziolo, M.; Postula, M. Climate Policy Development and Implementation from United Nations Sustainable Development Goals Perspective. 2022. Available online: https://assets.researchsquare.com/files/rs-1352892/v1/7b10d329-e983-432a-b98f-8f14a1929a61.pdf?c=1653323758 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Braathen, N.A.; Greene, J. Environmental Taxation. A guide for Policy Makers. From Taxation, Innovation and the Environment. 2011. Available online: www.oecd.org/env/taxes/innovation (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Van Kerckhoven, S.; Bécault, E.; Marx, A. Ecological tax reform initiatives in Africa. Int. J. Green Econ. 2015, 9, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westraadt, P. Ecological Taxation and South Africa’s Agricultural Sector: International Developments and Local Implications. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Africa (UNISA), Pretoria, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- African Tax Administration Forum. Environmental Taxes Defined. 2021. Available online: https://events.ataftax.org/includes/preview.php?file_id=143&language=en_US (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Nerudová, D.; Dobranschi, M. The Impact of Tax Burden Overshifting on the Pigovian Taxation. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 220, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smulders, S. Environmental Taxation in Open Economies: Trade Policy Distortions and the Double Dividend. In International Environmental Economics: A Survey of the Issues; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 166–182. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, W.K. Double dividend. In Encyclopedia of Energy, Natural Resource, and Environmental Economics, 1st ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pigou, A.C. Some Problems of Foreign Exchange. Econ. J. 1920, 30, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-González, J. Environmental taxation and the double dividend hypothesis in CGE modelling literature: A critical review. J. Policy Model. 2018, 40, 194–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekpe, M.T.; Emmanuel, O.G.; Josiah, M. Environmental Taxation: Issues and Benefits; Chartered Institute of Taxation of Nigeria: Alausa Ikeja, Nigeria, 2021; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Mooij, R.A. The double dividend on environmental tax reform. In Handbook of Environmental and Resource Economics; van der Bergh, J.C., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Northampton, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Andreoni, V. Environmental taxes: Drivers behind the revenue collected. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseh, P.K., Jr.; Lin, B. Environmental policy and ‘double dividend’ in a transitional economy. Energy Policy 2019, 134, 110947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. United Nations Handbook on Carbon Taxation for Developing Countries; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rotimi, O. Environmental Tax and Pollution Control in Nigeria. KIU Interdiscip. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 2, 280–301. [Google Scholar]

- Villar-Rubio, E.; Morales, M.D.H. Energy, transport, pollution and natural resources: Key elements in ecological taxation. Econ. Policy Energy Environ. 2016, 58, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Glossary of Statistical Terms: Environmental Taxes. 2004. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- OECD. Environmental Fiscal Reform: Progress, Prospects and Pitfalls. 2017. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/tax/environment-fiscal-reform-progress-prospects-and-ptfalls.htm (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- OECD. Taxing Energy for Sustainable Development. 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/taxing-energy-use-for-sustainable-development.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Shahzad, U. Environmental taxes, energy consumption, and environmental quality: Theoretical survey with policy implications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 24848–24862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigou, A.C. The Effect of Reparations on the Ratio of International Interchange. Econ. J. 1932, 42, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerudova, D.; Dobransch, M. Double dividend hypothesis: Can it occur when tackling carbon emissions? Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 12, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D. The Role of Carbon Taxes in Adjusting to Global Warming. Econ. J. 1991, 101, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulder, L.H. Environmental taxation and the double dividend: A reader’s guide. Int. Tax Public Financ. 1995, 2, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W.J.; Baumol, W.J.; Oates, W.E.; Bawa, V.S.; Bawa, W.S.; Bradford, D.F.; Baumol, W.J. The Theory of Environmental Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Baumol, W.J.; Oates, W.E. Economics, Environmental Policy, and the Quality of Life; Gregg Revivals: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.R.; Misiolek, W.S. Substituting pollution taxation for general taxation: Some implications for efficiency in pollutions taxation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1986, 13, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, P. Environmental Taxation and the Double Dividend: Fact or Fallacy; Earthscan: London, UK, 1997; pp. 106–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bovenberg, A.L.; Goulder, L.H. Green Tax Reforms and the Double Dividend: An Updated Reader’s Guide. In Environmental Policy Making in Economies with Prior Tax Distortions; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Babiker, M.H.; Metcalf, G.E.; Reilly, J. Tax distortions and global climate policy. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2003, 46, 269–287. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Lin, Z.; Du, H.; Feng, T.; Zuo, J. Do environmental taxes reduce air pollution? Evidence from fossil-fuel power plants in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulder, L.H. Climate change policy’s interactions with the tax system. Energy Econ. 2013, 40, S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, W.; Pan, X.; Hu, J.; Pu, G. Environmental tax reform and the “double dividend” hypothesis in a small open economy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slunge, D.; Sterner, T. Environmental Fiscal Reform in East and Southern Africa and Its Effects on Income Distribution. In Environmental Taxes and Fiscal Reform; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2012; pp. 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- De Mooij, R.A. Green Tax Reform in an Endogenous Growth Model. In Environmental Taxation and the Double Dividend; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Glomm, G.; Kawaguchi, D.; Sepulveda, F. Green taxes and double dividends in a dynamic economy. J. Policy Model. 2008, 30, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piciu, G.C.; Trică, C.L. Trends in the Evolution of Environmental Taxes. Procedia Econ. Finance 2012, 3, 716–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulder, L.H. Environmental Policy Making in Economies with Prior Tax Distortions; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Poterba, J.M.; Rotemberg, J.J. Environmental taxes on intermediate and final goods when both can be imported. Int. Tax Public Financ. 1995, 2, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovenberg, A. Green tax reforms and the double dividend: An updated reader’s guide. Int. Tax Public Financ. 1999, 6, 421–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayındır-Upmann, T.; Raith, M.G. Should high-tax countries pursue revenue-neutral ecological tax reforms? Eur. Econ. Rev. 2003, 47, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenert, D.; Schwerhoff, G.; Edenhofer, O.; Mattauch, L. Environmental taxation, inequality and Engel’s law: The double dividend of redistribution. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2018, 71, 605–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.T. Optimal Environmental Tax Rate in an Open Economy with Labor Migration—An E-DSGE Model Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinch, J.P.; Dunne, L.; Dresner, S. Environmental and wider implications of political impediments to environmental tax reform. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 960–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Golsanami, N. Tax Policy, Environmental Concern and Level of Emission Reduction. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebele-Mpofu, F.Y. Governance quality and tax morale and compliance in Zimbabwe’s informal sector. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1794662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebele-Mpofu, F.Y. The Informal Sector, the “implicit” Social Contract, the Willingness to Pay Taxes and Tax Compliance in Zimbabwe. Account. Econ. Law Conviv. 2021, 20200084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebele-Mpofu, F.Y.; Mashiri, E.; Korera, P. Transfer Pricing Audit Challenges and Dispute Resolution Effectiveness in Developing Countries with Specific Focus on Zimbabwe. Account. Econ. Law Conviv. 2021, 000010151520210026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpofu, F.Y.S. Informal Sector Taxation and Enforcement in African Countries: How plausible and achievable are the motives behind? A Critical Literature Review. Open Econ. 2021, 4, 72–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpofu, F.Y.S. Taxing the informal sector through presumptive taxes in Zimbabwe: An avenue for a broadened tax base, stifling of the informal sector activities or both. J. Account. Tax. 2021, 13, 153–177. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, B.; Li, Q. Green Technology Adoption in Textile Supply Chains with Environmental Taxes: Production, Pricing, and Competition. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kombat, A.M.; Wätzold, F. The emergence of environmental taxes in Ghana—A public choice analysis. Environ. Policy Gov. 2018, 29, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezenagu, A. Carbon Taxation as a Tool for Sustainable Development in Africa: Evaluation of Potentials, Paradoxes and Prospects. Paradoxes and Prospects. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alexander-Ezenagu/publication/318009315_Carbon_Taxation_as_a_Tool_for_Sustainable_Development_in_Africa_Evaluation_of_Potentials_Paradoxes_and_Prospects/links/59f7ff550f7e9b553ebef4a7/ (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Belletti, E. Environmental Taxation in Sub-Saharan Africa: Barriers and Policy Options. In Economic Instruments for a Low-Carbon Future; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 186–203. [Google Scholar]

- Zalik, A. Subjects of Extraction: Social Regulation, Corporate Aid and Petroleum Security in the Nigerian Delta and the Mexican. Master’s Thesis, Gulf. Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Náñez Alonso, S.L.; Jorge-Vázquez, J.; Echarte Fernández, M.Á.; Reier Forradellas, R.F. Cryptocurrency mining from an economic and environmental perspective. Analysis of the most and least sustainable countries. Energies 2021, 14, 4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putranti, I.R. Crypto Minning: Indonesia Carbon Tax Challenges and Safeguarding International Commitment on Human Security. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Soc. Dev. 2022, 3, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezenagu, A. Carbon Taxation as a Tool for Sustainable Development in the MENA Region: Potentials and Future Directions. In Climate Change Law and Policy in the Middle East and North Africa Region; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 187–203. [Google Scholar]

- Heine, D.; Black, S. Benefits Beyond Climate: Environmental Tax Reform. In Fiscal Policies for Development and Climate Action, 1st ed.; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- George, M.; Steven, J. An Assessment of Sand Extraction Environmental Externalities as a Source of Market Failure in Gweru District of Zimbabwe. Am. Res. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2022, 5, 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ellawule, A. Carbon Emissions and the Prospect of Double Dividend of Environmental Taxation in Nigeria. Afr. J. Sustain. Agric. Dev. 2021, 2, 2714–4402. [Google Scholar]

- Garba, I.; Jibir, A.; Bappayaya, B.; Bello, A. Externalities from air pollution and its health consequences. Does environmental tax matter? Int. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2018, 5, 805–822. [Google Scholar]

- Akintoye, I.R.; Oyedokun, G.E.; Agboola, H.T. 4th ICAN International Academic Conference Proceedings; Institute of Chartered Accountants of Nigeria (ICAN): Lagos, Nigeria, 2018; p. 487. [Google Scholar]

- Okubor, C.N. Legal Issues on Environmental Taxation. Ajayi Crowther Univ. Law J. 2017, 1. Available online: https://www.aculj.acuoyo.net/index.php/lj/article/viewFile/17/17 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Omodero, C.O.; Okafor, M.C.; Nmesirionye, J.A.; Abaa, E.O. Environmental Taxation and CO2 Emission Management. Environ. Ecol. Res. 2022, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirmenci, T.; Aydin, M. The effects of environmental taxes on environmental pollution and unemployment: A panel co-integration analysis on the validity of double dividend hypothesis for selected African countries. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garba, I. Community perception of implementation of environment taxation for sustainable development in Nigeria. India J. Econ. Dev. 2017, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tonderayi, D. Combating Greenhouse Gas Emissions in a Developing Country: A Conceptualisation and Implementation of Carbon Tax in Zimbabwe. J. Soc. Dev. Afr. 2012, 27, 163. [Google Scholar]

- Amesho, K.T. Financing renewable energy in Namibia: A fundamental key challenge to the sustainable development goal 7: Ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2019, 9, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Global Indicator Framework for Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In Work of the Statistical Commission Pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liyanage, S.I.H.; Netswera, F.G.; Motsumi, A. Insights from EU Policy Framework in Aligning Sustainable Finance for Sustainable Development in Africa and Asia. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2020, 11, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, T.E.; Karatu, K.; Edward, A. An evaluation of the environmental impact assessment practice in Uganda: Challenges and opportunities for achieving sustainable development. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, C.; Aradottir, A.L.; Hagen, D.; Halldórsson, G.; Høegh, K.; Mitchell, R.J.; Raulund-Rasmussen, K.; Svavarsdóttir, K.; Tolvanen, A.; Wilson, S.D. Evaluating the process of ecological restoration. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.; Chisholm, E.; Griggs, D.; Howden-Chapman, P.; McCollum, D.; Messerli, P.; Neumann, B.; Stevance, A.-S.; Visbeck, M.; Stafford-Smith, M. Mapping interactions between the sustainable development goals: Lessons learned and ways forward. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1489–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, D. Towards Integration at Last? The Sustainable Development Goals as a Network of Targets. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziolo, M.; Bak, I.; Cheba, K. The Role of Sustainable Finance in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals: Does it Work? Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2021, 27, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovgal, O.; Goncharenko, N.; Reshetnyak, O.; Dovgal, G.; Danko, N.; Shuba, T. Sustainable Ecological Development of the Global Economic System. The Institutional Aspect. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2020, 11, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G.; Gkampoura, E.-C. Where do we stand on the 17 Sustainable Development Goals? An overview on progress. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 70, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G.; Gkampoura, E.C. Reviewing the 17 Sustainable Development Goals: Importance and Progress. 2021. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/105329/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Halkos, G.E.; Gkampoura, E.-C. Coping with Energy Poverty: Measurements, Drivers, Impacts, and Solutions. Energies 2021, 14, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future (Report on World Commission on Environment and Development); Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann, R.; Mieg, H.A.; Frischknecht, P. Principal sustainability components: Empirical analysis of synergies between the three pillars of sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpofu, F.Y.S. Review Articles: A Critical Review of the Pitfalls and Guidelines to effectively conducting and reporting reviews. Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 18, 550. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J.; El-Geneidy, A. What is a good transport review paper? Transp. Rev. 2022, 42, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, S.; Wohlin, C. Systematic Literature Studies: Database Searches vs. Backward Snowballing. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM-IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement, Lund, Sweden, 20–21 September 2012; pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wee, B.V.; Banister, D. How to write a literature review paper? Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, W.; Miskon, S.; Fielt, E. A Systematic, Tool-Supported Method for Conducting Literature Reviews in Information Systems. In Proceedings of the 19th European Conference on Information Systems ECIS 2011, Helsinki, Finland, 9–11 June 2011; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sebele-Mpofu, F.Y. Saturation controversy in qualitative research: Complexities and underlying assumptions. A literature review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 1838706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolbridge, M. From MDGs to SDGs: What are the Sustainable Development Goals? ICLEI Briefing Sheet, 1-Urban Issue (1). 2015. Available online: https://www.local2030.org/library/251/From-MDGs-to-SDGs-What-are-the-Sustainable-Development-Goals.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Mhlanga, D. Stakeholder Capitalism, the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), and Sustainable Development: Issues to Be Resolved. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, D. Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence: The Superlative Approach to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burak, Ö.K.D.E. Differences between Turkey and EU Countries on Taxation Policy for Electric Vehicles. J. Account. Tax. Stud. 2022, 15, 415–435. [Google Scholar]

- Nanez Alonso, S.L. The tax incentives in the IVTM and “Eco-Friendly Cars”: The Spanish case. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Ponce, P.; Yu, Z. Technological innovation and environmental taxes toward a carbon-free economy: An empirical study in the context of COP-21. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R. Double-Dividend Hypothesis and Competitiveness: A Critical Examination. In Fiscal Control of Pollution; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 189–218. [Google Scholar]

| Principle | Explanation |

|---|---|

| The polluter pays principle | This principle relates to the quantification of positive and negative impacts. The principal advocates for internalization and calls for accounting for pollution through the fiscal and economic approach. In this case, the tax cost must reflect the internalized cost of the environmental damage linked to an economic activity. The principle calls for the environmental costs that are not only borne by society (through social impacts) and governments (through costs to redress the degradation) but also by the polluter through taxation in the case of green taxes. |

| The principle of prevention | This principle advocates for the protection of the environment. The idea is to ensure that as companies and individuals exploit resources for their economic development and profit maximization, they do not cause damage to the environment. Green taxes are one such economic measure for prevention of the environment through policies that protect the environment and ensure environmental sustainability. |

| The precautionary principle | This principle is founded on the desire to protect the environment from potential risks or harm. The harm might be currently unassessed, unquantified, or unaccounted for, but there is a possibility of estimating it justifiably (hypothetical risk). Environmental taxes can help mitigate future risks and protect the environment. |

| The principle of common but differentiated responsibilities | The principle is based on countries having a shared responsibility for protecting the environment against degradation and pollution although with differentiated engagement levels. Environmental taxes could provide a common ground that is differentiated by the nature of the green taxes, the tax rates as well as the tax administration. |

| Studies (Authors) | Country | Methodology | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ellawule and Balewa [62] | Nigeria | Review of legislation | Nigeria could benefit from the implementation of environmental taxes and achieve the double dividend hypothesis. Researchers recommended the imposition of carbon taxes on carbon emissions. |

| Garba et al. [63] | Nigeria | Survey | Air pollution is harmful to the health and well-being of citizens, and environmental taxes might help alleviate environmental-polluting activities if the polluter is made to pay. |

| Oyedokun et al. [64] | Nigeria | Descriptive survey design | Environmental taxes and accounting may not have resulted in the anticipated mitigation of environmental challenges. |

| Okubor [65] | Nigeria | Literature Review | The imposition of environmental taxes led to a significant increase in revenue collections to fund government expenditure and green taxes. |

| Omodero et al. [66] | Nigeria | Regression analysis (2010 to 2020 data) | To promote clean water and air (SDG6) and sustainable energy use (SDG 7), environmental taxes are key. The taxes include gas exploration tax, gas flaring penalties and petroleum tax. |

| Kombat and Watzold [53] | Ghana | Assessing environmental taxes (taxes on plastics, old vehicles and petroleum) using | Environmental taxes contribute to reducing environmental problems. The taxes have a potential to significantly mitigate environmental damages if supported by effective tax administration (which is the biggest weakness of African countries due to fragile capacities). |

| Degirmenci and Aydin [67] | Cameroon, Mali, South Africa, Ivory Coast and Uganda | Assessing the validity of the double dividend theory using panel integration and longrun estimates | Environmental taxes fueled environmental degradation and unemployment in Cameroon, Ivory Coast and Mali. In South Africa and Uganda, these taxes led to environmental restoration and employment, respectively. The research concluded that in general, the double dividend is not valid for African countries. |

| Garba [68] | Nigeria | Survey (close ended questions) | Political acceptance, value benefits, trust and ethical beliefs are the key factors in explaining environmental policy acceptance levels in Nigeria. |

| Tonderayi [69] | Zimbabwe | Literature review | Carbon taxes are not delivering their objectives of environmental protection and preservation possibly due to financial, human, and technical challenges. In Zimbabwe, the carbon tax has lost its deterrence effect. The fact that it is incorporated in fuel makes it hidden and not felt by motorists. There are no clear scientific computations to support the emission estimates or the charge. The taxes are more of a revenue-generating tool than environmental protection measure. |

| SDG | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Poverty eradication |

| 2 | No hunger |

| 3 | Promoting good health and well-being |

| 4 | Providing inclusive and equitable quality education |

| 5 | Ensuring gender equality and empowerment of women and girls |

| 6 | Provision of clean water and sanitation to facilitate economic development and improve the quality of life |

| 7 | Ensuring access to affordable and clean energy |

| 8 | Provision of decent work and promoting sustainable and inclusive economic growth |

| 9 | Promoting sustainable and inclusive industrialization, increased research and innovation and development of resilient infrastructure |

| 10 | Ensuring a reduction in inequalities |

| 11 | Building sustainable, inclusive, resilient, and safe cities and communities |

| 12 | Fostering responsible consumption and production |

| 13 | Taking action to address climate change and its impact |

| 14 | Preservation and protection of life below water |

| 15 | Preservation and protection of life on the land |

| 16 | Promoting peace, justice, and strong institutions |

| 17 | Building partnerships to achieve the goals |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mpofu, F.Y. Green Taxes in Africa: Opportunities and Challenges for Environmental Protection, Sustainability, and the Attainment of Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610239

Mpofu FY. Green Taxes in Africa: Opportunities and Challenges for Environmental Protection, Sustainability, and the Attainment of Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610239

Chicago/Turabian StyleMpofu, Favourate Y. 2022. "Green Taxes in Africa: Opportunities and Challenges for Environmental Protection, Sustainability, and the Attainment of Sustainable Development Goals" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610239

APA StyleMpofu, F. Y. (2022). Green Taxes in Africa: Opportunities and Challenges for Environmental Protection, Sustainability, and the Attainment of Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability, 14(16), 10239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610239