Gender Segregation at Work over Business Cycle—Evidence from Selected EU Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of Literature

3. Materials and Methods

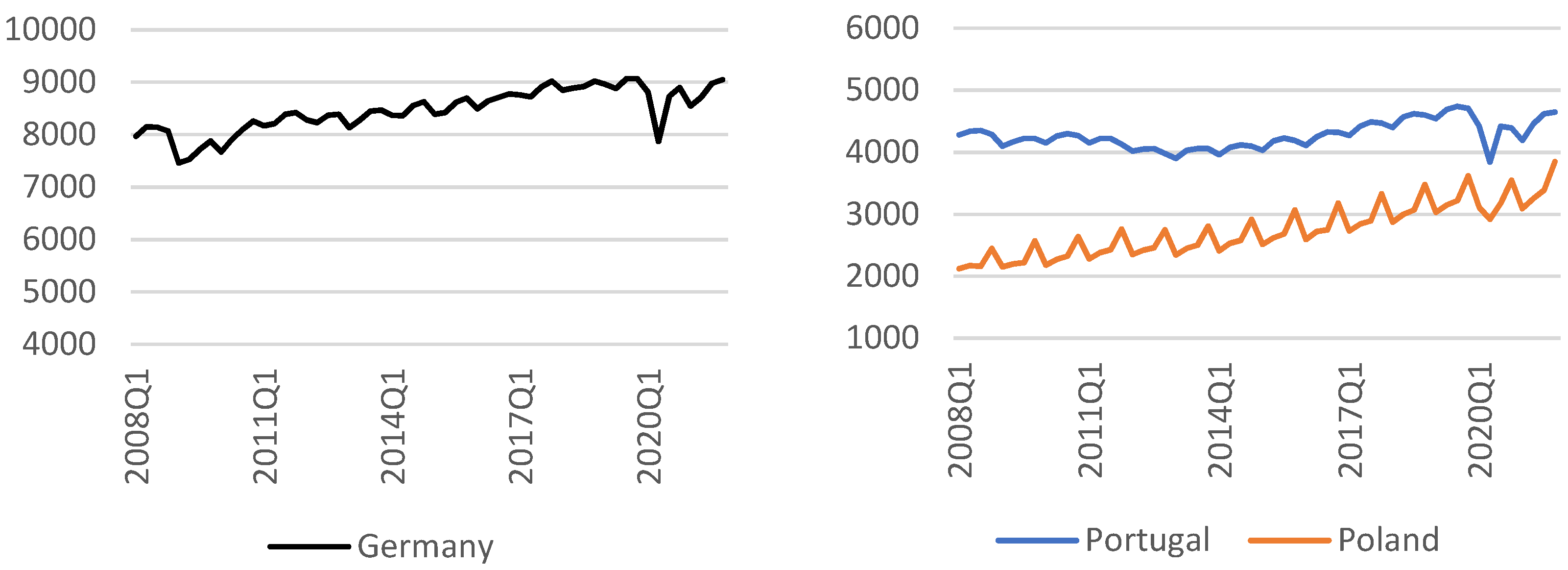

3.1. Country Specific Characteristics and Data

3.2. Methods

4. Results

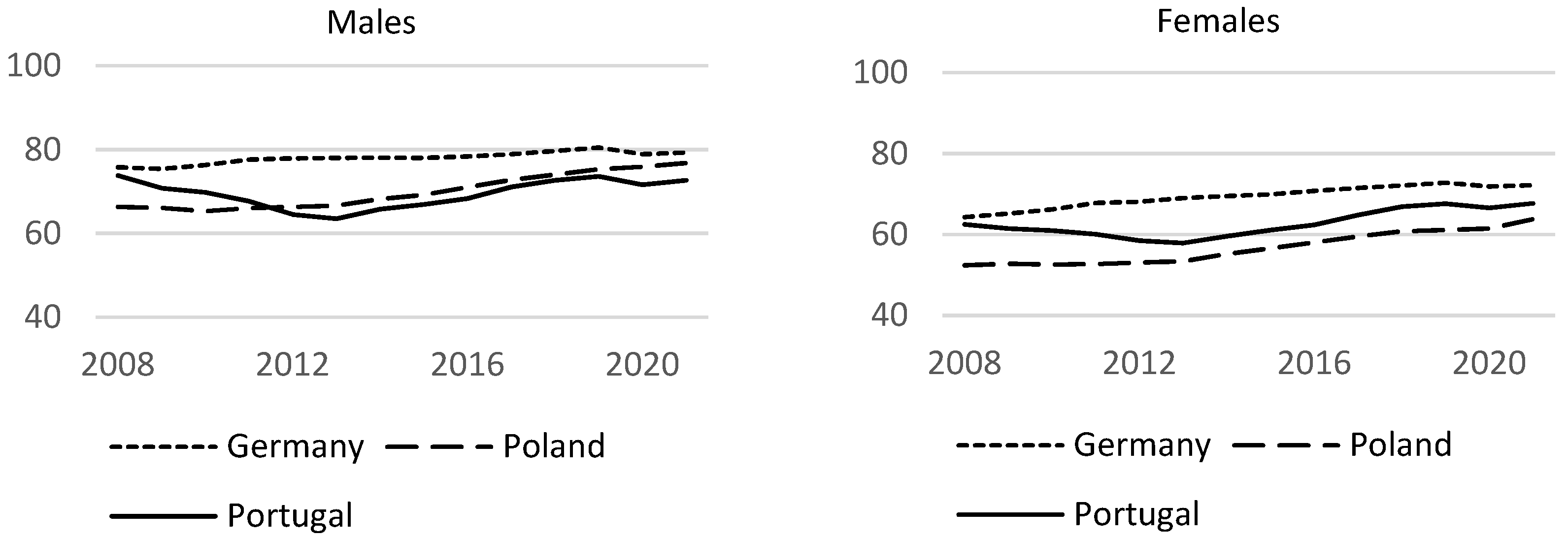

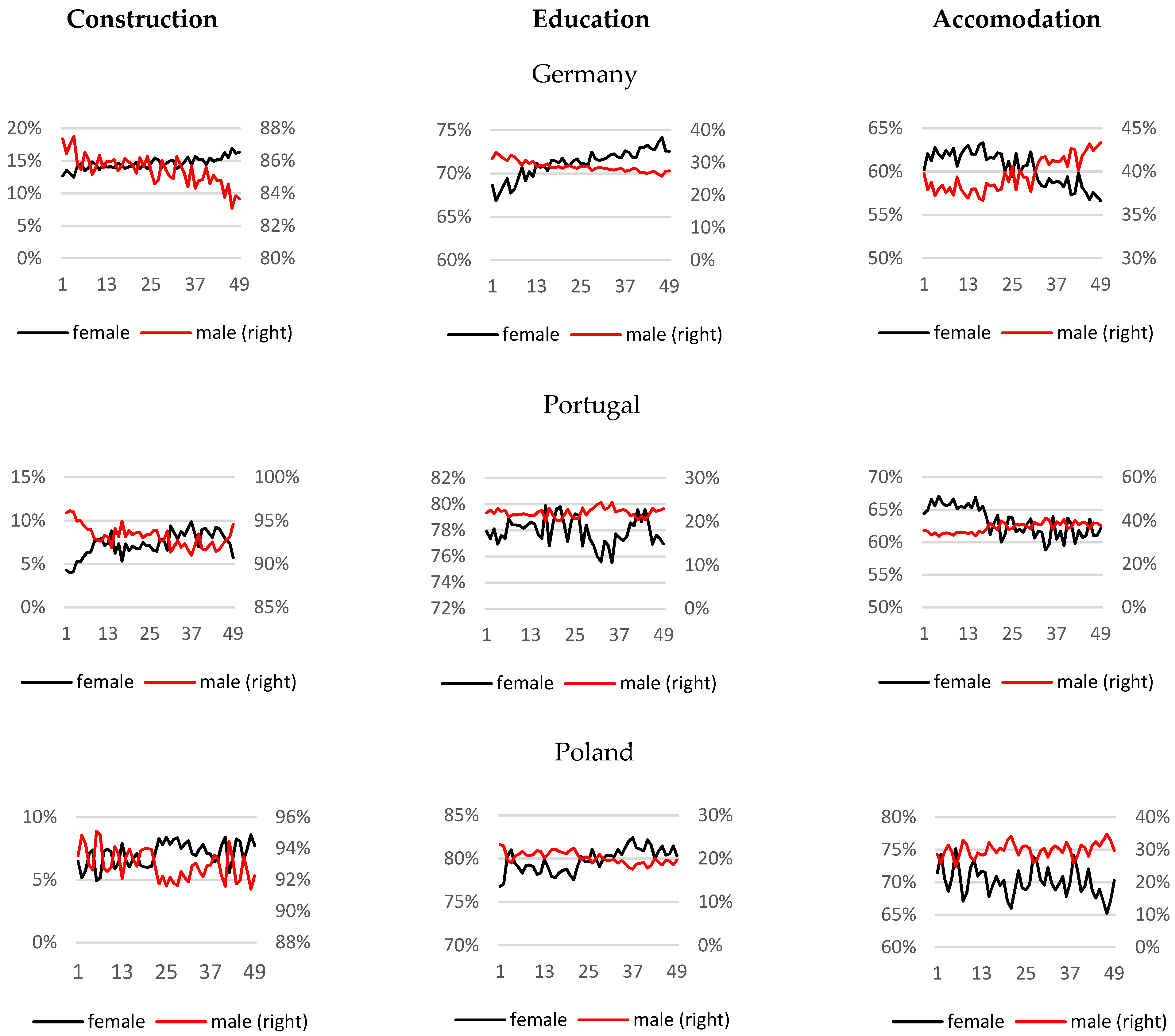

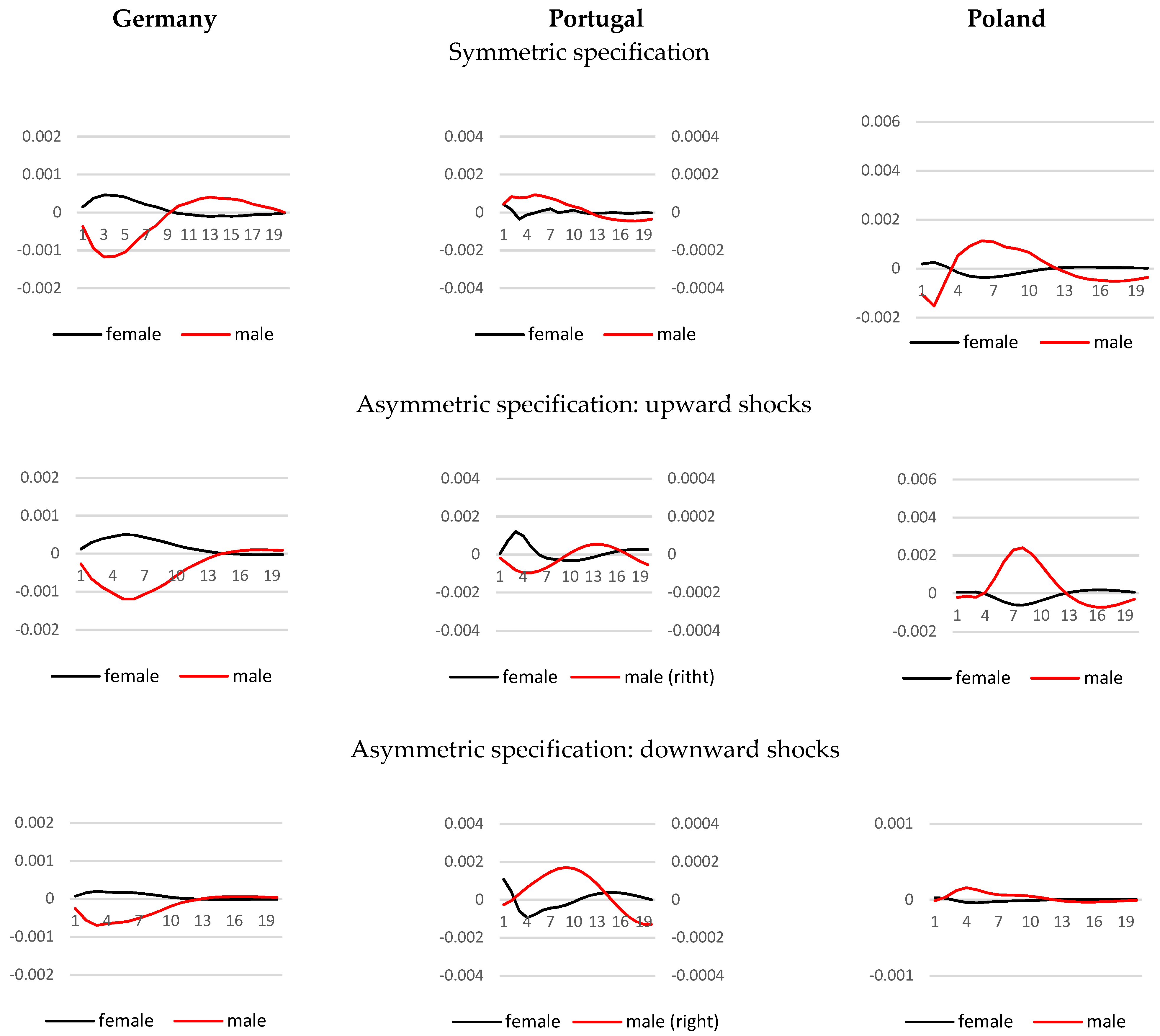

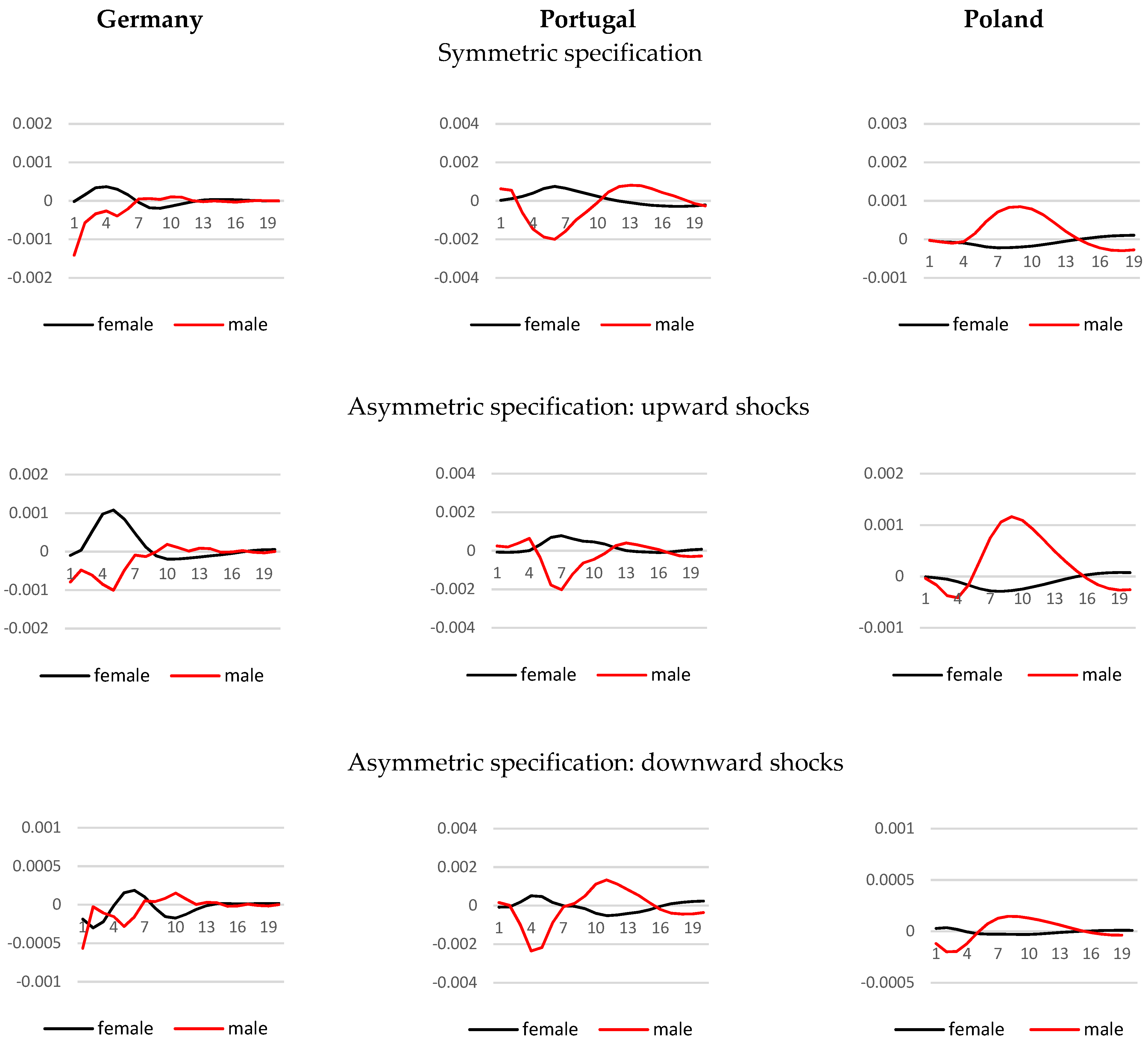

4.1. Effects of Changes in GDP on Fluctuations in Gender Employment Rate

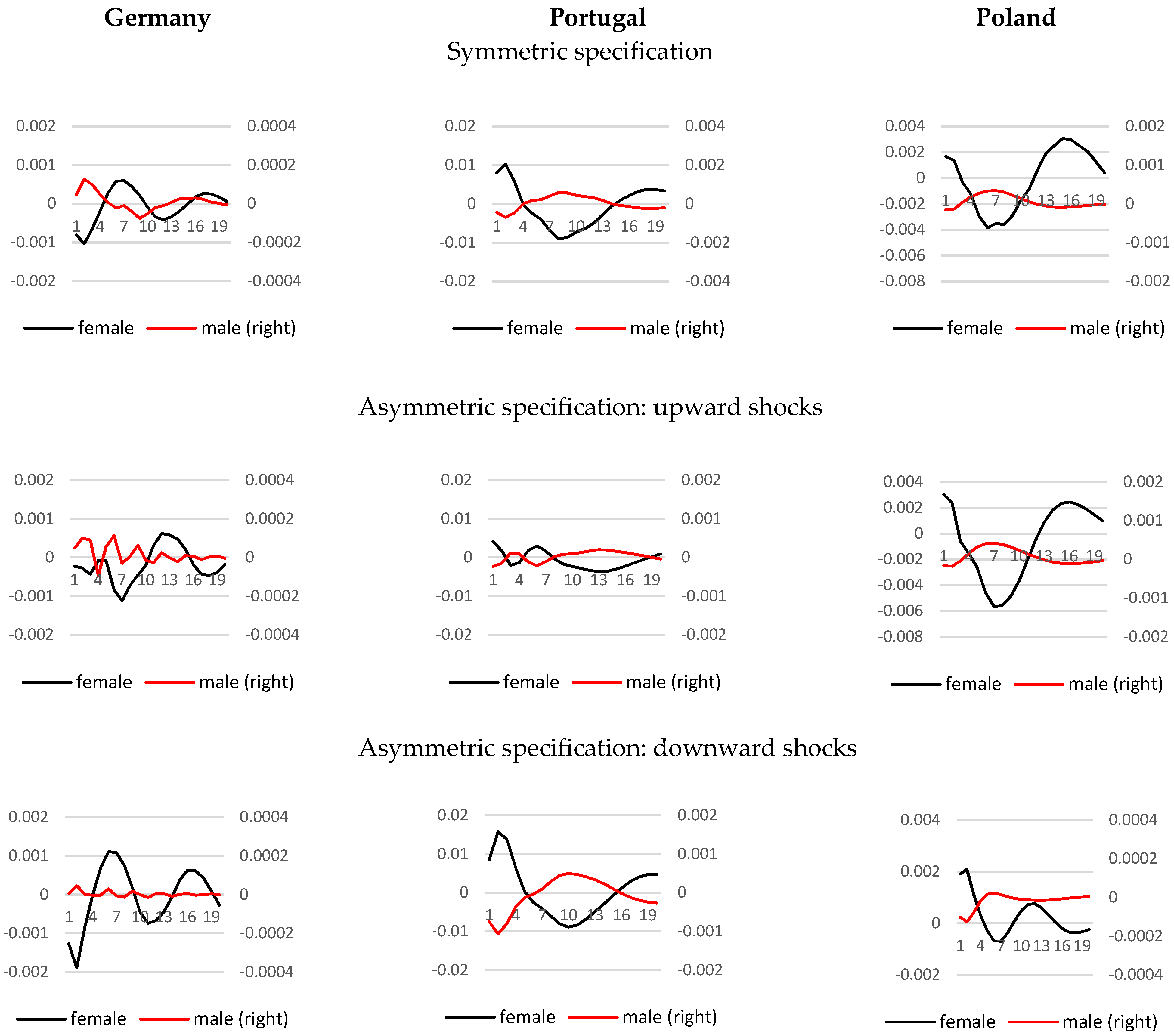

4.2. Responses of Employment Rate to GDP Shocks—Impulse Response Functions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Périvier, H. Men and women during the economic crisis. Rev. l’OFCE 2014, 2, 41–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsby, M.; Hobijn, B.; Sahin, A.; Elsby, M.; Hobijn, B.; Sahin, A. The labor market in the great recession. Brook. Pap Econ Act. 2010, 41, 1–69. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/article/binbpeajo/v_3a41_3ay_3a2010_3ai_3a2010-01_3ap_3a1-69.htm (accessed on 17 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- EIGE. Gender Segregation in Education, Training and the Labour Market. 2017. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/about-eige/procurement/eige-2016-oper-13 (accessed on 8 February 2020).

- Borrowman, M.; Klasen, S. Drivers of Gendered Sectoral and Occupational Segregation in Developing Countries. 2017. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/157267 (accessed on 29 September 2019).

- Hedija, V. Sector-specific gender pay gap: Evidence from the European union countries. Econ. Res. Istraz. 2017, 30, 1804–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boll, C.; Leppin, J.; Rossen, A.; Wolf, A. Justice and Consumers Magnitude and Impact Factors of the Gender Pay Gap in EU Countries; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions on Strengthening the Commitment and Stepping Up Action to Close the Gender Pay Gap, and on the Review of the Implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action. 2010. Available online: http://register.consilium.europa.eu/doc/srv?l=EN&f=ST 16881 2010 INIT (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- Evans, J.M. Work/Family Reconciliation, gender wage equity and occupational segregation: The role of firms and public policy. Can. Public Policy/Anal. Polit. 2002, 28, S187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.B.; Summers, L.H.; Clark, K.B.; Summers, L. Demographic differences in cyclical employment variation. J. Hum. Resour. 1981, 16, 61–79. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/article/uwpjhriss/v_3a16_3ay_3a1981_3ai_3a1_3ap_3a61-79.htm (accessed on 15 October 2019). [CrossRef]

- Rives, J.M.; Sosin, K. Occupations and the cyclical behavior of gender unemployment rates. J. Socio. Econ. 2002, 31, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. 1990. Available online: https://lanekenworthy.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/reading-espingandersen1990pp9to78.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Cerami, A. The politics of reforms in Bismarckian Welfare systems: The cases of Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia. In Paper Presented at the Conference “A Long Good Bye to Bismark? The Politics of Welfare Reforms in Continental Europe”; Harvard University: Cambridge, UK, 2006; Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.545.6134&rep- =rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- Schlenker, E. The labour supply of women in STEM. IZA J. Eur. Labor Stud. 2015, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbritti, M.; Fahr, S. Downward wage rigidity and business cycle asymmetries. J. Monet. Econ. 2013, 60, 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, B. Further evidence on the asymmetric behavior of economic time series over the business cycle. J. Political Econ. 1986, 94, 1096–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, D. The asymmetric cyclical behavior of the U.S. labor market. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2018, 30, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.D. A new approach to the economic analysis of nonstationary time series and the business cycle. Econometrica 1989, 57, 357–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, J.; Piger, J. The asymmetric business cycle. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2012, 94, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neftçi, S.N. Are economic time series asymmetric over the business cycle? J. Polit. Econ. 1984, 92, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R.; Macurdy, T. Labor Supply: A Review of Alternative Approaches. 1999. Available online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/~uctp39a/Blundell-MaCurdy-1999.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Booth, A.L.; Francesconi, M.; Garcia-Serrano, C. Job tenure and job mobility in Britain. ILR Rev. 1999, 53, 43–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, J.; Hart, R.A.; Vecchi, M. Labour Force Participation and the Business Cycle: A Comparative Analysis of Europe, Japan and the United States; Business School-Economics, University of Glasgow: Glasgow, UK, 1998; Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/gla/glaewp/9802.html (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Hotchkiss, J.L.; Robertson, J.C. Asymmetric Labor Force Participation Decisions over the Business Cycle: Evidence from US Microdata; FRB Atlanta Working Papers: No. 8; Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koop, G.; Potter, S.M. Dynamic asymmetries in U.S. unemployment. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 1999, 17, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzu, G.; Singleton, C. Gender and the business cycle: An analysis of labour markets in the US and UK. J. Macroecon. 2016, 47, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubery, J. Women and Recession; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rubery, J.; Rafferty, A. Women and recession revisited. Work Employ. Soc. 2013, 27, 414–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, D. Gender disparities in the labor market in the EU. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 2013, 19, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, R.; Rocca, A. Gender disparities in European labour markets: A comparison between female and male employees. Int. Labour Rev. 2018, 157, 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, M.; Longhi, S. Couples’ labour supply responses to job loss: Growth and recession compared. Manch. Sch. 2017, 86, 333–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berik, G.; Kongar, E. Time allocation of married mothers and fathers in hard times: The 2007–09 US Recession. Fem. Econ. 2013, 19, 208–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C. The rise in women’s share of nonfarm employment during the 2007–2009 recession: A historical perspective. Mon. Lab. Rev. 2014, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettio, F.; Verashchagina, A. Gender Segregation in the Labour Market: Root Causes, Implications and Policy Responses in the EU; European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities, Unit G: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, R.M.; Jarman, J.; Brooks, B. The puzzle of gender segregation and inequality: A cross-national analysis. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 16, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincer, J.; Polachek, S. Family investments in human capital: Earnings of women. J. Polit. Econ. 1974, 82, 76–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walby, S. Patriarchy at Work; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Walby, S. Theorizing Patriarchy; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim, C. Work-Lifestyle Choices in the 21st Century: Preference Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, R.M.; Browne, J.; Brooks, B.; Jarman, J. Explaining gender segregation. Br. J. Sociol. 2002, 53, 513–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, M.S.; Nadler, J.T. Paradigmatic assumptions of disciplinary research on gender disparities: The case of occupational sex segregation. Sex Roles 2013, 68, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, A.; Smith, N. Women, Jobs and Opportunity in the 21st Century; USA Department of Labour: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- EIGE. Study and Work in EU: Set Apart by Gender. 2018. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications/study-and-work-eu-set-apart-gender-report (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Das, S.; Kotikula, A. Gender-Based Employment Segregation: Understanding Causes and Policy Interventions. 2019. Available online: www.worldbank.org (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- Witkowska, D.; Kompa, K.; Matuszewska-Janica, A. Sytuacja Kobiet na Rynku Pracy—Wbrane Aspekty; PWN: Łódź, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hillmert, S. Gender segregation in occupational expectations and in the labour market: International variation and the role of education and training systems. Comp. Soc. Res. 2015, 31, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, M.; Bradley, K. Indulging our gendered selves? Sex segregation by field of study in 44 countries. Am. J. Sociol. 2009, 114, 924–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, S.L.; Gelbgiser, D.; Weeden, K.A. Feeding the pipeline: Gender, occupational plans, and college major selection. Soc. Sci. Res. 2013, 42, 989–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabay-Egozi, L.; Shavit, Y.; Yaish, M. Gender differences in fields of study: The role of significant others and rational choice motivations. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 31, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Women, Men and Working Conditions in Europe: A Report Based on the Fifth European Working Conditions Survey; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013; Available online: http://eurogender.eige.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EF1349EN.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- European Parliament. Indicators of Job Quality in the European Union—IP/A/EMPL/ST/2008-09. 2009. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/document/activities/cont/201107/20110718ATT24284/20110718-ATT24284EN.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Piore, M.J. Dualism in the Labor Market: A Response to Uncertainty and Flux. The Case of France. Rev. Économique 1978, 29, 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.N. The persistence of workplace gender segregation in the US. Sociol. Compass. 2013, 7, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M. Occupational Segregation and the Gender Pay Gap. 2017. Available online: http://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/research/understanding-implicit-bias (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- Hegewisch, A.; Liepmann, H.; Hayes, J.; Hartmann, H. Separate and not equal? Gender segregation in the labor market and the gender wage gap. In Briefing Paper, Pay Equity & Discrimination; Institute for Women’s Policy Research, C377: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Available online: https://iwpr.org/publications/separate-and-not-equal-gender-segregation-in-the-labor-market-and-the-gender-wage-gap (accessed on 17 February 2019).

- Blau, F.D.; Kahn, L.M. Swimming upstream: Trends in the gender wage differential in the 1980s. J. Labor Econ. 1997, 15, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. Analysis Note: The Gender Pay Gap in the EU–What policy responses? In European Network of Experts on Employment and Gender Equality Issues (EGGE); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2010; Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.191.874 (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- O’Reilly, J.; Smith, M.; Deakin, S.; Burchell, B. Equal Pay as a Moving Target: International perspectives on forty-years of addressing the gender pay gap. Camb. J. Econ. 2015, 39, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandil, M.; Woods, J.G. Convergence of the gender gap over the business cycle: A sectoral investigation. J. Econ. Bus. 2002, 54, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehmke, E.; Lindner, F. Labour Market Measures in Germany 2008-13: The Crisis and Beyond; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: www.ilo.org/publns (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Cardoso, D.; Branco, R. Labour Market Reforms and the Crisis in Portugal: No change, U-Turn or New Departure? 2017 IPRI Working Papers: No. 56; NOVA University of Lisbon: Lisbon, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewski, P. Labour Market Measures in Poland 2008-13: The Crisis and Beyond; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: www.ilo.org/publns (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- EC. Special Eurobarometer European Commission Gender Equality in the EU in 2009 Report. 2009. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=418 (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Razzu, G.; Singleton, C. Segregation and gender gaps in the United Kingdom’s great recession and recovery. Fem. Econ. 2018, 24, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.; Campbell, J.; Thomson, E.; Ross, S. Economic recession and recovery in the UK: What’s gender got to do with it? Fem. Econ. 2013, 19, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, S.; Weber, E. GDP-Employment Decoupling and the Slow-Down of Productivity Growth in Germany GDP-Employment Decoupling and the Slow-Down of Productivity Growth in Germany; IAB-Discussion Raport, No. 12; Institute for Employment Research: Nuremberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–36. Available online: http://doku.iab.de/discussionpapers/2019/dp1219.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- EC. European Semester Thematic Factsheet: Undeclared Work. 2018, pp. 1–199. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326922410_European_semester_thematic_factsheet_undeclared_work (accessed on 21 November 2019).

- Hutchings, M. What impact does the wider economic situation have on teachers’ career decisions? In A Literature Review Merryn Hutchings Institute for Policy Studies in Education; London Metropolitan University: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg, A. Women and men’s employment in the recessions of the 1990s and 2000s in Sweden. Rev. L’ofce 2014, 2, 303–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Boockmann, B. Die Größe der Schattenwirtschaft-Methodik und Berechnungen für das Jahr 2015. 2015. Available online: http://www.econ.jku.at/schneider (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Ferrera, M. The “Southern Model” of welfare in social Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 1996, 6, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C.; Bejakovii, P.; Mikulii, D.; Franic, J.; Kedir, A.; Horodnic, I.A. An Evaluation of the Scale of Undeclared Work in the European Union and Its Structural Determinants: Estimates Using the Labour Input Method; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimova, D. The Structural Determinants of the Labor Share in Europe; IMF Work Pap; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Volume 19, p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T. International Perspectives on Women and Work in Hotels, Catering and Tourism; ILO Working Paper, No. 1; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: www.ilo.org/publns (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- EC. Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2014-Publications Office of the EU. 2014. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/bc35c135-a0ca-4aae-8404-e3777f69a0b3/language-en (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- EC. Report on Equality between Women and Men in the EU; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construction | Education | Accommodation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | Males |

| Germany | 0.25 (0.99) | 1.88 (0.93) | 6.35 (0.38) | 5.72 (0.46) | 2.95 (0.57) | 3.79 (0.44) |

| Poland | 5.17 (0.52) | 4.91 (0.3) | 4.66 (0.32) | 5.26 (0.51) | 12.3 (0.02) * | 12.1 (0.02) * |

| Portugal | 8.5 (0.04) * | 10.5 (0.02) * | 2.74 (0.84) | 3.93 (0.69) | 6.5 (0.37) | 8.83 (0.18) |

| Causality: | Construction | Education | Accommodation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | |

| Germany | ||||||

| 6.73 (0.15) | 4.04 (0.4) | 9.2 (0.06) * | 8.68 (0.07) * | 15.8 (0.003) * | 30.7 (0.00) * | |

| 7.07 (0.13) | 1.3 (0.86) | 12.5 (0.01) * | 10.7 (0.03) * | 7.23 (0.1) | 9.78 (0.04) * | |

| Asymmetric effects | 5.42 (0.03) * | 0.19 (0.67) | 4.16 (0.05) * | 3.85 (0.06) * | 5.86 (0.02) * | 21.8 (0.000) * |

| Poland | ||||||

| 5.69 (0.22) | 3.77 (0.29) | 5.54 (0.14) | 5.67 (0.13) | 10.54 (0.02) * | 8.04 (0.05) * | |

| 2.4 (0.66) | 1.02 (0.8) | 4.5 (0.21) | 5.28 (0.15) | 0.37 (0.95) | 3.42 (0.33) | |

| Asymmetric effects | 3.38 (0.07) | 1.79 (0.19) | 3.13 (0.08) | 3.73 (0.06) | 0.08 (0.78) | 0.22 (0.64) |

| Portugal | ||||||

| 1.31 (0.52) | 2.53 (0.28) | 8.15 (0.02) * | 8.8 (0.03) * | 12.7 (0.012) * | 10.2 (0.04) * | |

| 6.23 (0.04) * | 6.31 (0.04) * | 5.62 (0.06) * | 8.0 (0.05) * | 11.8 (0.02) * | 8.21 (0.08) * | |

| Asymmetric effects | 9.19 (0.004) * | 7.75 (0.01) * | 0.53 (0.47) | 0.03 (0.86) | 0.6 (0.44) | 0.1 (0.76) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piłatowska, M.; Witkowska, D. Gender Segregation at Work over Business Cycle—Evidence from Selected EU Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610202

Piłatowska M, Witkowska D. Gender Segregation at Work over Business Cycle—Evidence from Selected EU Countries. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610202

Chicago/Turabian StylePiłatowska, Mariola, and Dorota Witkowska. 2022. "Gender Segregation at Work over Business Cycle—Evidence from Selected EU Countries" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610202

APA StylePiłatowska, M., & Witkowska, D. (2022). Gender Segregation at Work over Business Cycle—Evidence from Selected EU Countries. Sustainability, 14(16), 10202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610202