Understanding the Scientific Topics in the Chinese Government’s Communication about COVID-19: An LDA Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Scientific Topics in Government Communications about COVID-19

2.1.1. Government Communications about COVID-19

2.1.2. Government Framing of Scientific Topics Surrounding COVID-19

2.1.3. Topics of Sustainability Science in Communications about COVID-19

2.2. The Social Environment Characteristics of Government Communication

2.2.1. Agenda Setting: Interaction with the Public and Media

2.2.2. Modulating Factors: Sources and Severity

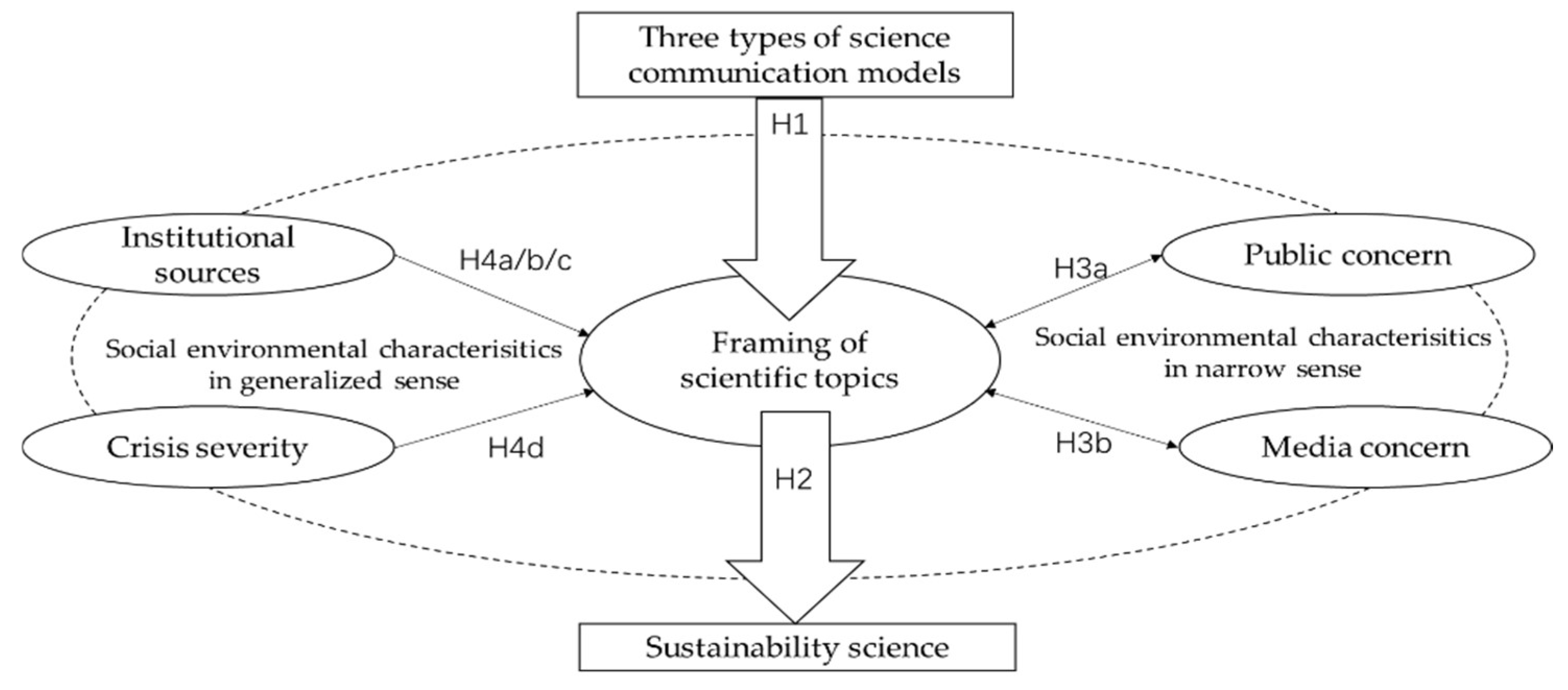

2.3. Research Model

3. Materials and Methods

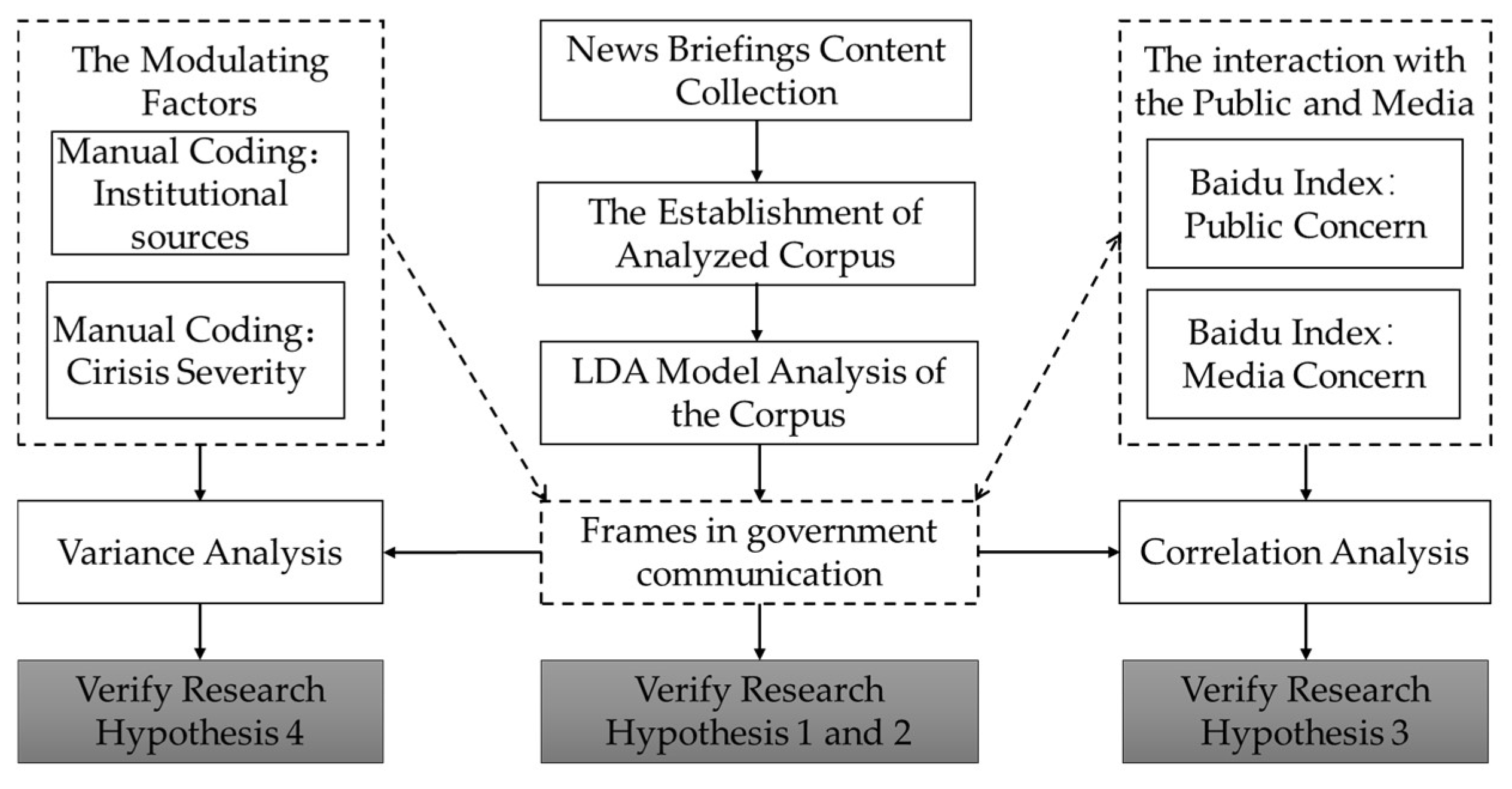

3.1. News Briefing Content Collection

3.2. Establishment of a Corpus Concerning Science-Related Content

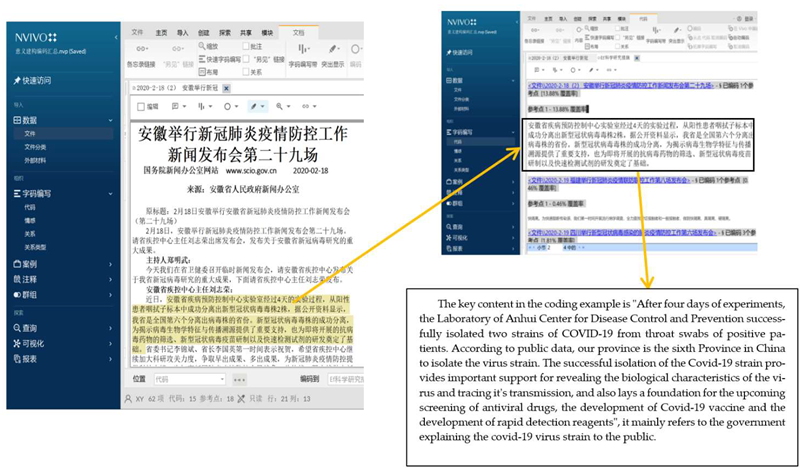

3.2.1. Import Materials into NVivo Software

3.2.2. Training Coders

3.2.3. Coding of the Science-Related Content

3.3. Measuring the Framing of Scientific Topics: LDA Model Analysis

3.3.1. Preprocessing of Text

3.3.2. Generation of An LDA Topic Model

3.3.3. Determination of the Optimal Number of Topics

3.3.4. Generation of Word Weights in Each Topic and the Distance of Topics

3.3.5. Generation of the Topic Weights of Each Corpus

3.4. Verifying the Interaction among the Government, Public, and Media

3.5. Verifying the Factors That Modulate Government Communication

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Scientific Topics in the Chinese Government’s Communications

4.1.1. Science Communication Models

4.1.2. Topics Concerning Sustainability Science

4.2. Social Environmental Characteristics of the Scientific Topics

4.2.1. Interaction with the Public and Media

4.2.2. Institutional Sources

4.2.3. Crisis Severity

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Major Findings and Contributions

5.1.1. Identification of the Patterns of Science Communication Models in the Chinese Government’s Communication about COVID-19

5.1.2. Verification of the Interaction among Government Frames, Public Concern, and Media Concern about COVID-19

5.1.3. Identification of Factors That Modulate Government Framing of Scientific Topics about COVID-19

5.1.4. The Topics Concerning Sustainability Science were More Correlated with Public Concern and Media Concern

5.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Text Composition and Source of News Briefing

Appendix B. An Example of Coding Science-Related Content

| News briefing material: 18 February 2020 Anhui | |

| Coder information: Coder 1; Coding time: 9 September 2021; Coding location: Beijing | |

| Science content: Public understanding of science | |

| News briefing material: The 29th COVID-19 prevention and control news briefing announced by Anhui Province | Corpus concerning science-related content: Coding in NVIVO |

| |

References

- Taragin-Zeller, L.; Rozenblum, Y.; Baram-Tsabari, A. Public engagement with science among religious minorities: Lessons from COVID-19. Sci. Commun. 2020, 42, 643–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Esparcia, A.; Fernández-Souto, A.B.; Puentes-Rivera, I. Political communication and COVID-19: Strategies of the Government of Spain. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, e290419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Llaguno, M.; Ballestar, M.T.; Cuerdo-Mir, M.; Sainz, J. From Ignorance to Distrust: The Public “Discovery” of COVID-19 Around International Women’s Day in Spain. Int. J. Commun. 2022, 16, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Antiochou, K. Science communication: Challenges and dilemmas in the age of COVID-19. Hist. Philos. Life Sci. 2021, 43, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.N. Some lessons from COVID: Science and communication. IUCrJ 2021, 8, 331–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, M. From top scientist to science media star during COVID-19-South Africa’s Salim Abdool Karim. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2020, 116, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hut, R.; Land-Zandstra, A.M.; Smeets, I.; Stoof, C.R. Geoscience on television: A review of science communication literature in the context of geosciences. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 20, 2507–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, A.; Gajevic, S. Selling science? Source struggles, public relations, and UK press coverage of animal–human hybrid embryos. J. Stud. 2013, 14, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.M.; VanDyke, M.S. Set it and forget it: The one-way use of social media by government agencies communicating science. Sci. Commun. 2015, 37, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kerckhove, D.T.; Rennie, M.D.; Cormier, R. Censoring government scientists and the role of consensus in science advice: A structured process for scientific advice in governments and peer-review in academia should shape science communication strategies. EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, H.J. Integrating Two Traditions:Also Talking about Our Understanding of Science Communication. Nanjing J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 10, 6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippmann, W. Public Opinion, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- McCombs, M.E.; Shaw, D.L. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin. Q. 1972, 36, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R.M. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, R.; Scholten, P. Framing the immigration policy agenda: A qualitative comparative analysis of media effects on Dutch immigration policies. Int. J. Press/Polit. 2017, 22, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, B.F.; Horsley, J.S.; Levenshus, A.B. Government and corporate communication practices: Do the differences matter? J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2010, 38, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollust, S.E.; Nagler, R.H.; Fowler, E.F. The emergence of COVID-19 in the US: A public health and political communication crisis. J. Health Polit. Policy Law 2020, 45, 967–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MA, S.; Pande, N.; PK, S.K. Role of effective crisis communication by the government in managing the first wave Covid-19 pandemic—A study of Kerala government’s success. J. Public Aff. 2021, 21, e2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphree, V.; Reber, B.H.; Blevens, F. Superhero, instructor, optimist: FEMA and the frames of disaster in Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. J. Public Relat. Res. 2009, 21, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankard, J.W. Media Frames: Approaches to Conceptualization and Measurement; The Association for Education: Boston, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Edy, J.A.; Meirick, P.C. Wanted, dead or alive: Media frames, frame adoption, and support for the war in Afghanistan. J. Commun. 2007, 57, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, C.A.; Zhou, X. Within the boundaries of politics: News framing of SARS in China and the United States. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2005, 82, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.H.; Gower, K.K. Framing effect on the public’s response to crisis: Human interest frame and crisis type influencing responsibility and blame. Public Relat. Rev. 2006, 32, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semetko, H.A.; Valkenburg, P.M. Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news. J. Commun. 2000, 50, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.J.; Wijaya, R.; Brossard, D. Media coverage of public health epidemics: Linking framing and issue attention cycle toward an integrated theory of print news coverage of epidemics. Mass Commun. Soc. 2008, 11, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.W.; Naylor, P.J.; Berry, T.; O’Connor, B.; McLean, D. The health buck stops where? Thematic framing of health discourse to understand the context for CVD prevention. J. Health Commun. 2006, 11, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Dorantes-Gilardi, R.; Xiang, Z.; Aron, L. COVID-19 Twitter Communication of Major Societal Stakeholders: Health Institutions, the Government, and the News Media. Int. J. Commun. 2021, 15, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Q.; Yuan, J.; Dong, M.; Yang, L.; Fielding, R.; Tak Lam, W.W. Public engagement and government responsiveness in the communications about COVID-19 during the early epidemic stage in China: Infodemiology study on social media data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chandra, Y.; Fan, Y. Unpacking government social media messaging strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Policy Internet, 2021; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska, A.; Dobija, D.; Grossi, G.; Staniszewska, Z. Getting through COVID-19 together: Understanding local governments’ social media communication. Cities 2022, 121, 103453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. Making Science: Between Nature and Society, 1st ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bucchi, M.; Trench, B. Handbook of Public Communication of Science and Technology, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M. Reviewed Work: Misunderstanding Science? The Public Reconstruction of Science and Technology by A. Irwin, B. Wynne. Br. J. Sociol. 1997, 48, 156–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne, B. Public uptake of science: A case for institutional reflexivity. Public Underst. Sci. 1993, 2, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cantos, F. The impact on public trust of image manipulation in science. Inf. Sci. 2019, 22, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beattie, A.; Priestley, R. Fighting COVID-19 with the team of 5 million: Aotearoa New Zealand government communication during the 2020 lockdown. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open. 2021, 4, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durant, J. Participatory technology assessment and the democratic model of the public understanding of science. Sci. Public Policy 1999, 26, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenfeld, L.; Smith, H.M.; Norton, T.; Grecu, N.C. Risk communication and sustainability science: Lessons from the field. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernicova-Buca, M.; Palea, A. An appraisal of communication practices demonstrated by Romanian district public health authorities at the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, M.; Leidenberger, J. COVID-19 as a window of opportunity for sustainability transitions? Narratives and communication strategies beyond the pandemic. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2020, 16, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.H.; Gu, X.Y. Principles and Practice of Public Relations, 2nd ed.; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2006; p. 421. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jámbor, A.; Czine, P.; Balogh, P. The impact of the coronavirus on agriculture: First evidence based on global newspapers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balázs, B.; Horváth, J.; Pataki, G. Science-society dialogue from the start: Participatory research agenda-setting by Science Cafés. Eur. J. Futures Res. 2020, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P.R. Dark tourism: Towards a new post-disciplinary research agenda. Int. J. Tour. Anthropol. 2011, 1, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Li, Y.; Cheng, C.Y.; Zhao, H.; Meng, T. Government-led or public-led? Chinese policy agenda setting during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Comp. Policy Anal. 2021, 23, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, C.A.; Blanco-Herrero, D.; Oller-Alonso, M. Trusting communication of the pandemic: The perceptions of Spanish citizens regarding government information on COVID-19. Prof. Inf. 2021, 30, e300606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahariadis, N.; Ceccoli, S.; Petridou, E. Assessing the effects of calculated inaction on national responses to the COVID-19 crisis. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 2021, 12, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandl, B.J.; Reis, B.Y. The language of crisis: Spatiotemporal effects of COVID-19 pandemic dynamics on health crisis communications by political leaders. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, A.I.; Gruber, J.B. Political agenda setting in the hybrid media system: Why legacy media still matter a great deal. Int. J. Press Polit. 2021, 26, 313–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, H.; Platt, L.S. Examining risk and crisis communications of government agencies and stakeholders during early-stages of COVID-19 on Twitter. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriluță, N.; Stoica, V.; Fârte, G.I. The Official Website as an Essential E-Governance Tool: A Compara-tive Analysis of the Romanian Cities’ Websites in 2019 and 2022. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fissi, S.; Gori, E.; Romolini, A. Social media government communication and stakeholder engagement in the era of COVID-19: Evidence from Italy. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2022, 35, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, C.Y.; Wu, Y.H. Affective communication: A mixed method investigation into COVID-19 outbreak communication using the Taiwanese government Facebook page. Glob. Health Promot. 2021, 28, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.Y.; Chen, S.Y.; Lai, Y.T. Investigating COVID-19 news before and after the soft lockdown: An example from Taiwan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salton, G.; Buckley, C. Term-weighting approaches in automatic text retrieval. Inf. Process. Manag. 1988, 24, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deerwester, S.; Dumais, S.T.; Furnas, G.W.; Landauer, T.K.; Harshman, R. Indexing by latent semantic analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1990, 41, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.H.; Tian, R.Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, X.F. Overview on Microblog Topic Detection Methods. Libr. Inf. Serv. 2017, 61, 141. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Ma, X.F. Visual Analysis of Domestic Status of the LDA Model. Inf. Res. 2020, 11, 7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, J.; Ren, J.; Qin, C.; Kurcz, K. Understanding the topics of export cross-border e-commerce consumers feedback: An LDA approach. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 19, 749–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimno, D.; Wallach, H.M.; Talley, E.; Leenders, M.; McCallum, A. Optimizing semantic coherence in topic models. In Proceedings of the 2011 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Edinburgh, UK, 27–29 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mamipour, S.; Yahoo, M.; Jalalvandi, S. An empirical analysis of the relationship between the environment, economy, and society: Results of a PCA-VAR model for Iran. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 102, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La, V.-P.; Pham, T.-H.; Ho, M.-T.; Nguyen, M.-H.; Nguyen, K.-L.P.; Vuong, T.-T.; Nguyen, H.-K.T.; Tran, T.; Khuc, Q.; Ho, M.-T.; et al. Policy response, social media and science journalism for the sustainability of the public health system amid the COVID-19 outbreak: The Vietnam lessons. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Chen, K. Effective Risk Communication for Public Health Emergency: Reflection on the COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) Outbreak in Wuhan, China. Healthcare 2020, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hong, H.; Kim, H.J. Antecedents and consequences of information overload in the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Communication Models | Communication Patterns | Possible Scientific Topics in Current Research | Purposes of Government Communications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Popularization of scientific knowledge | One-way and disposable | Etiology, virus transmission pathways, and disease prevention [27]; knowledge to dispel rumors [28]; public health knowledge [30]; | Inculcation and popularization of scientific knowledge. |

| Public understanding of science | Consultation | vaccines R&D, specific drugs R&D, and effective treatments [27]; medical resources [29]. | Explanation of the process of scientific knowledge, namely scientific research. |

| Public participation in science | Multi-subject participation | Public participation [28,29,36]; community involvement [28]. | Co-production of scientific knowledge and participation in scientific decision making. |

| Factors | Measurable Variables | Coding | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional sources | Types of government agencies | 1 = Health 2 = Education 3 = Economy 4 = Social forces 5 = Communist party 6 = Other departments | Artificial recognition |

| Officials’ level | 1 = No rank (volunteers, doctors, staff, etc.) 2 = Grassroots officers (junior level and below) 3 = Senior officials (deputy director and above) | Artificial recognition | |

| Region of government holding the news briefing | 1 = Low-income regions (ranked 22–31) 2 = Middle-income regions (ranked 12–21) 3 = High-income regions (top 11) | The World Bank’s ranking of income levels China’s GDP per capita ranking | |

| Crisis severity | Periods | 1 = Outbreak period (21 January 2020–20 February 2020) 2 = Spread control period (21 February 2020–17 March 2020) 3 = Victory period (18 March 2020–28 April 2020) 4 = Regular epidemic period (29 April 2020–27 August 2021) | A white paper titled China’s actions to fight the COVID-19 pandemic published by Xinhua News in June 2020 |

| Number of daily new cases | 1 = No new cases 2 = The number of new cases ranged from 1 to 10 3 = The number of new cases ranged from 11 to 100 4 = More than 100 new cases | Artificial recognition |

| Topics | Topic Words and Weights | Models |

|---|---|---|

| Topic 1: Chinese Medicine Treatment and Research and Development | 0.014 × ”R&D” + 0.011 × ”Research” + 0.010 × ”Pandemic” + 0.010 × ”Clinical” + 0.009 × ”Science and Research” + 0.008 × ”Treatment” + 0.008 × ”Prevention and control” + 0.008 × ”Chinese Medicine” + 0.008 × ”COVID-19” + 0.008 × ”Testing” | Public understanding of science |

| Topic 2: Knowledge of Epidemiological Investigation | 0.033 × ”Epidemiology” + 0.033 × ”Investigation” + 0.012 × ”Testing” + 0.009 × ”Patients” + 0.008 × ”Cases” + 0.007 × ”Examine” + 0.007 × ”Epidemiological investigation” + 0.007 × ”Virus” + 0.007 × ”Close contact” + 0.006 × ”Nucleic acids” | Popularization of scientific knowledge |

| Topic 3: Vaccination and R&D of Vaccines | 0.026 × ”Vaccines” + 0.018 × ”Inoculation” + 0.014 × ”Pandemic” + 0.007 × ”Prevention and control” + 0.006 × ”R&D” + 0.006 × ”Beijing” + 0.005 × ”COVID-19” + 0.005 × ”Community” + 0.005 × ”Publish” + 0.004 × ”Duration” | Public understanding of science |

| Topic 4: Enterprise Technology Development | 0.031 × ”Pandemic” + 0.027 × ”Prevention and control” + 0.020 × ”Enterprise” + 0.008 × ”Resumption of work” + 0.006 × ”Organization” + 0.005 × ”Technology” + 0.004 × ”Resumption of production” + 0.004 × ”Development” + 0.004 × ”Services” + 0.004 × ”Deployment” | Public understanding of science |

| Topic 5: Public Participation in Prevention and Control | 0.037 × ”Publicity” + 0.028 × ”Health” + 0.015 × ”Prevention and control” + 0.014 × ”Civilization” + 0.014 × ”Knowledge” + 0.012 × ”Pandemic” + 0.009 × ”Guide” + 0.009 × ”Citizens” + 0.009 × ”Activities” + 0.008 × ”Media” | Public participation in science |

| Topic 6: Enterprise Involvement in Prevention and Control | 0.017 × ”Pandemic” + 0.016 × ”Prevention and control + 0.010 × ”Cases” + 0.008 × ”Enterprise” + 0.008 × ”Supplies” + 0.007 × ”Emergency response” + 0.007 × ”Health” + 0.007 × ”Implementation” + 0.007 × ”Location” + 0.006 × ”Safeguard” | Public participation in science |

| Topic 7: Treatment Options | 0.011 × ”Cases of disease” + 0.009 × ”Pandemic” + 0.008 × ”Isolation” + 0.007 × ”Treatment” + 0.007 × ”Patients” + 0.006 × ”Diagnosis” + 0.006 × ”Crowd” + 0.006 × ”Asymptomatic infection” + 0.006 × ”Infected persons” + 0.005 × ”Prevention and control” | Public understanding of science |

| Topic 8: Medical Resources | 0.014 × ”Platform” + 0.013 × ”Pandemic” + 0.008 × ”COVID-19” + 0.007 × ”Prevention and control” + 0.007 × ”COVID” + 0.007 × ”Citizens” + 0.007 × ”Beijing” + 0.007 × ”Enquiries” + 0.007 × ”Doctors” + 0.006 × ”Coronavirus” | Public understanding of science |

| Topic 9: Knowledge of Prevention and Control | 0.035 × ”Pandemic” + 0.030 × ”Prevention and control” + 0.013 × ”Measures” + 0.009 × ”Gathering” + 0.009 × ”Risks” + 0.007 × ”Cases of disease“ + 0.007 × ”Health” + 0.007 × ”Implementation” + 0.007 × ”Testing” + 0.006 × ”Protection” | Popularization of scientific knowledge |

| Topic 10: Community Participation in Prevention and Control | 0.035 × ”Prevention and control” + 0.029 × ”Community” + 0.025 × ”Pandemic” + 0.010 × ”Services” + 0.008 × ”The Crowd” + 0.007 × ”Organization” + 0.007 × ”Crowd” + 0.007 × ”Village” + 0.006 × ”Health” + 0.006 × ”Publicity” | Public participation in science |

| Topic 11: Knowledge of Personal Health | 0.021 × “Mask” + 0.018 × “Disinfection” + 0.010 × “Hour” + 0.010 × “Wear”+ 0.009 × ”Health” + 0.009 × “Psychology” + 0.008 × “Use” + 0.007 × “Ventilation” + 0.007 × ”Protection” + 0.006 × ”Testing” | Popularization of scientific knowledge |

| Public Understanding of Science | Scientific Knowledge Popularization | Public Participation in Science | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 9 | 11 | 5 | 6 | 10 | |

| Topic | Chinese Medicine | Vaccines | Enterprise R&D | Treatment Options | Medical Resources | Investigation | Prevention and Control | Personal Health | Public | Enterprise | Community |

| Public concern | −0.047 | −0.020 | 0.067 ** | −0.036 | 0.080 ** | −0.013 | −0.107 ** | −0.089 ** | −0.016 | −0.004 | 0.175 ** |

| Media concern | 0.109 ** | 0.028 | 0.088 ** | 0.038 | 0.000 | −0.08 ** | −0.066 ** | 0.030 | −0.103 ** | −0.025 | 0.025 |

| Public Understanding of Science | Scientific Knowledge Popularization | Public Participation in Science | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 9 | 11 | 5 | 6 | 10 | ||

| Chinese Medicine | Vaccine R&D | Enterprise R&D | Treat-Ment Options | Medical Resources | Investigation | Prevention and Control | Personal Health | Public | Enterprise | Community | ||

| Officials’ level | 1 | 0.0791 | 0.0584 | 0.0830 | 0.0773 | 0.0746 | 0.0989 | 0.0803 | 0.1388 | 0.1554 | 0.0500 | 0.0825 |

| 2 | 0.0682 | 0.0809 | 0.0546 | 0.0492 | 0.0345 | 0.0646 | 0.1319 | 0.0700 | 0.1983 | 0.0639 | 0.1631 | |

| 3 | 0.0885 | 0.0496 | 0.1147 | 0.0578 | 0.0257 | 0.0692 | 0.1260 | 0.0586 | 0.1866 | 0.0619 | 0.1389 | |

| F | 1.225 | 4.344 * | 9.455 *** | 1.467 | 12.318 *** | 1.891 | 2.715 | 14.504 *** | 1.266 | 0.413 | 5.413 ** | |

| Types of agencies | 1 | 0.0706 | 0.0679 | 0.0616 | 0.0689 | 0.0332 | 0.0910 | 0.1645 | 0.0915 | 0.1858 | 0.0414 | 0.1014 |

| 2 | 0.0690 | 0.0219 | 0.0880 | 0.0626 | 0.0464 | 0.1001 | 0.0480 | 0.1621 | 0.1488 | 0.0821 | 0.1526 | |

| 3 | 0.0887 | 0.0518 | 0.2683 | 0.0663 | 0.0090 | 0.0182 | 0.1194 | 0.0123 | 0.1617 | 0.1001 | 0.0746 | |

| 4 | 0.0745 | 0.0189 | 0.1573 | 0.0530 | 0.1087 | 0.0359 | 0.0380 | 0.0448 | 0.1954 | 0.0776 | 0.1758 | |

| 5 | 0.0401 | 0.0321 | 0.0939 | 0.0419 | 0.0353 | 0.0414 | 0.0744 | 0.0308 | 0.2538 | 0.0778 | 0.2560 | |

| 6 | 0.1145 | 0.0581 | 0.1294 | 0.0467 | 0.0220 | 0.0583 | 0.0978 | 0.0460 | 0.1735 | 0.0752 | 0.1566 | |

| F | 4.248 ** | 2.467 * | 13.062 *** | 1.362 | 7.007 *** | 4.129 ** | 9.258 *** | 10.498 *** | 2.151 | 3.978 ** | 10.76 *** | |

| Regions of different income | 1 | 0.0235 | 0.0386 | 0.1518 | 0.0483 | 0.0328 | 0.0987 | 0.1403 | 0.0723 | 0.1616 | 0.0685 | 0.1399 |

| 2 | 0.0820 | 0.0167 | 0.1185 | 0.0553 | 0.0463 | 0.0581 | 0.0943 | 0.0338 | 0.2398 | 0.0554 | 0.1718 | |

| 3 | 0.0904 | 0.0565 | 0.0846 | 0.0561 | 0.0334 | 0.0789 | 0.1032 | 0.0626 | 0.2155 | 0.0547 | 0.1425 | |

| F | 5.013 ** | 11.041 *** | 4.697 ** | 0.8 | 2.301 | 3.743 * | 11.054 *** | 9.755 *** | 24.111 *** | 1.95 | 3.808 ** | |

| Public Understanding of Science | Scientific Knowledge Popularization | Public Participation in Science | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic | 1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 9 | 11 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Chinese Medicine | Vaccine R&D | Enterprise R&D | Treatment | Medical Resources | Investigation | Prevention and Control | Personal Health | Public | Enterprise | Community | ||

| Period | 1 | 0.0593 | 0.0600 | 0.1312 | 0.0578 | 0.0419 | 0.0624 | 0.1012 | 0.0778 | 0.1347 | 0.0586 | 0.1927 |

| 2 | 0.1047 | 0.0484 | 0.1194 | 0.0620 | 0.0260 | 0.0475 | 0.1401 | 0.0506 | 0.1684 | 0.0716 | 0.1395 | |

| 3 | 0.0971 | 0.0505 | 0.0710 | 0.0423 | 0.0283 | 0.0493 | 0.1451 | 0.0784 | 0.2551 | 0.0580 | 0.1020 | |

| 4 | 0.0865 | 0.0675 | 0.0596 | 0.0731 | 0.0283 | 0.1343 | 0.1145 | 0.0619 | 0.2054 | 0.0588 | 0.0891 | |

| F | 4.104 ** | 0.949 | 10.08 *** | 2.026 | 1.764 | 15.523 ** | 3.086 * | 2.096 | 15.073 *** | 0.517 | 15.260 *** | |

| Cases | 1 | 0.0966 | 0.0442 | 0.0868 | 0.0494 | 0.0324 | 0.0698 | 0.1316 | 0.0723 | 0.2240 | 0.0532 | 0.1181 |

| 2 | 0.0632 | 0.0789 | 0.0957 | 0.0805 | 0.0314 | 0.0702 | 0.1021 | 0.0757 | 0.1671 | 0.0732 | 0.1397 | |

| 3 | 0.0483 | 0.0626 | 0.1323 | 0.0379 | 0.0383 | 0.0870 | 0.1421 | 0.0585 | 0.1251 | 0.0472 | 0.1975 | |

| 4 | 0.2457 | 0.0172 | 0.1461 | 0.0835 | 0.0162 | 0.0250 | 0.0746 | 0.0176 | 0.0909 | 0.1387 | 0.1235 | |

| F | 15.969 *** | 5.287 ** | 3.489 * | 5.093 ** | 0.554 | 1.578 | 2.653 * | 2.070 | 11.739 *** | 5.836 ** | 6.467 *** | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, Q.; Xue, Y.; Zhao, Z. Understanding the Scientific Topics in the Chinese Government’s Communication about COVID-19: An LDA Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159614

Xie Q, Xue Y, Zhao Z. Understanding the Scientific Topics in the Chinese Government’s Communication about COVID-19: An LDA Approach. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159614

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Qihui, Yanan Xue, and Zhuojun Zhao. 2022. "Understanding the Scientific Topics in the Chinese Government’s Communication about COVID-19: An LDA Approach" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159614

APA StyleXie, Q., Xue, Y., & Zhao, Z. (2022). Understanding the Scientific Topics in the Chinese Government’s Communication about COVID-19: An LDA Approach. Sustainability, 14(15), 9614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159614