Abstract

Demographic aging has led to an increase in the number of people with multiple needs requiring different types of care delivered by formal and informal carers. The distribution of care tasks between formal and informal carers has a significant impact on the well-being of carers and on how efficiently care is delivered to users. The study has two aims. The first is to explore how task division in care for older people differs between two neighboring countries with different forms of familialism: Slovenia (prescribed familialism) and Austria (supported familialism). The second is to explore how income and gender are associated with task division across these forms of familialism. Multinomial logistic regression is applied to SHARE data (wave 6, 2015) to estimate five different models of task division, based on how personal care and household help are distributed between formal and informal carers. The findings show that the task division is markedly different between Slovenia and Austria, with complementation and supplementation models more frequent in Austria. Despite generous cash benefits and higher service availability in Austria, pro-rich inequalities in the use of formal care only are pervasive here, unlike in Slovenia. Both countries show evidence of pro-poor inequalities in the use of informal care only, while these inequalities are mostly absent from mixed models of task division. Generous cash transfers do not appear to reduce gender inequalities in supported familialism. Supported familialism may not fundamentally improve inequalities when compared with less generous forms of familialism.

1. Introduction

Care for frail older people consists of a wide range of tasks, ranging from personal care to home help, which address different needs and that are associated with different consequences in terms of the caregiving burden or the ability to conciliate informal care with paid work [1,2]. Understanding how personal care and home help tasks are divided between formal and informal carers could improve the targeting of long-term care benefits to frail older people and ensure a more efficient and sustainable mix of care provision in the future. This is particularly relevant in the context of demographic aging which has led to an increase in the number of people with care needs generally [3], and in particular of those older people with multiple needs that require different types of care delivered by a range of formal and informal carers. As a result, pressure has been mounting on both formal and informal carers to provide additional care and to divide or share care tasks more efficiently. Against this backdrop, analyzing task division is likely to provide a more granular picture of inequalities, unmet needs, and outcomes of care than simply considering the use of different types of care.

While informal care remains the main source of care across Europe, countries still differ significantly in their patterns of formal and informal care use and these differences are likely to subsist in the near future. These different care regimes, defined around the varying importance attributed by public policies to the family as the main caregiver, are also labeled as different levels of familialism [4,5,6]. Most studies on task division of home help and personal care tasks between formal and informal carers have focused on individual countries [7,8,9]. Thus, there is little or no information available on how task division between formal and informal carers varies across countries defined by their degree of familialism. The first aim of this study is to bridge this gap and describe differences in task division between two neighboring countries with similar aging and health profiles, as well as family norms but different levels of familialism: Slovenia (prescribed familialism) and Austria (supported familialism). By employing a ‘most similar case’ comparison between countries that share a similar demographic age profile, family norms, care culture, and preferences, this study is better able to isolate the effect of dissimilar public policies on care task division. Slovenia is considering a reform of its long-term care system that would entail greater support for informal carers, namely cash benefits similar to those currently in place in Austria. This move towards cash-for-care benefits has also been implemented in other countries across Europe [10]. The comparison of these two strands of familialism thus has relevance beyond the two countries analyzed.

The literature on care regimes has identified socio-economic and gender inequalities in the use of formal and informal care across the various types of familialism. For example, socio-economic inequalities appear to be larger in countries where family members are the main carers (i.e., in countries characterized by familialism as opposed to de-familialism) with poorer individuals less likely to use formal care [11,12]. Given the inverse relationship between need and ability to pay, SEC inequalities could in turn negatively affect the outcomes and wellbeing of users of care and their informal carers. However, many of these studies have not considered either mixed forms of care provision (i.e., formal and informal care used together) or disaggregated care tasks (i.e., who receives personal care and home help and from whom). There are reasons to presume that inequalities across different types of familialism may extend to how care tasks are divided. For example, cash benefits present in supported familialism may allow for increased opportunities for lower-income families to purchase care services to carry out certain tasks, while this option may be more limited under the prescribed familialism. Conversely, greater informal care support under-supported familialism could, on the one hand, enable outsourcing of care by women, while, on the other hand, increasing the incentives for those same women to provide informal care, resulting in an ambiguous effect on gender inequalities in comparison to prescribed familialism. Therefore, the second aim of this study is to explore how socio-economic condition (SEC) and gender are linked to task division across different forms of familialism.

2. Background

2.1. Typology of Task Division

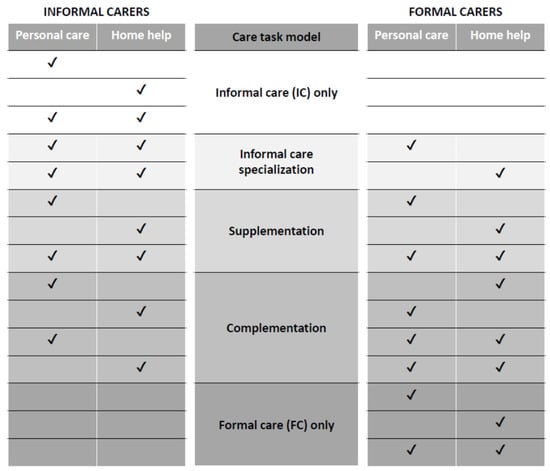

A large volume of literature addresses the task division between formal and informal carers, usually distinguishing between several models of task division along the lines of who provides home help tasks or support with IADL (Instrumental Activities of Daily Living), and/or personal care tasks or support with ADL (Activities of Daily Living). The main models of task division discussed in the literature are:

- -

- Informal care only model: Also termed kin independence [7], in which care tasks are provided solely by informal carers, who are often the closest and most available individuals and thus assumed to be preferred by older people [13];

- -

- Informal specialization model: At least one type of task is provided by the informal carer alone, while other tasks are performed by the formal and informal carer together [8];

- -

- Supplementation model: One or more tasks are performed jointly by the formal and informal carer, with the former topping up or supplementing the care provision with the latter, usually when the increase in care needs or overburdening of the informal carer may render her/him unable to fully address the care needs [14];

- -

- Complementation model: In this model of task division, formal and informal carers each perform different non-overlapping tasks [15]; or both carers share one type of task and the other task is carried out by the formal carer alone [7];

- -

- Formal care only model: Based on Green’s [16] substitution model in which care tasks are provided only by formal carers who fully substitute informal caregiving.

The previously described complementation model combines a model with a complete division of tasks between formal and informal carers—also termed dual specialization [15]—with one in which formal carers perform one task alone and other tasks are performed by both formal and informal carers—also referred to as formal specialization [7,8,9]. A defining characteristic of both models is that they completely outsource at least one task to formal carers. In addition, empirical evidence indicates that both models share the same determinants [8], namely the longer duration of care provision (more than 3 months), but with lower intensity of care (i.e., number of hours) and with a lower associated caregiver burden. Figure 1 summarizes the typology of task division based on the previously described models and used in this study.

Figure 1.

Typology of task division between formal and informal carers.

2.2. Care Regimes and Inequalities in Care

The differences between formal and informal care in Europe have been framed around the concept of care regimes or varieties of familialism, distinguishing between defamilialism, in which the state reduces the family’s care obligations by providing public services, and familialism, in which public policies explicitly support the family as sole or main care provider [4,5,17]. A number of intermediate forms can be identified along the familialism–defamilialism continuum. Saraceno [6] distinguishes familialism by default, in which family care takes place in a context where there are no formal care alternatives; prescribed familialism, with obligations to care or provide financial support to pay for care by the family being reinforced through law; and supported familialism, in which public policies actively support the caring role of the family, usually through cash benefits or care leave schemes. Other authors distinguish between the coexistence of public policies supporting family carers (namely cash benefits) with no or weak service development from the coexistence of such policies with care services developed through the market that at least provide some possibility to outsource care—dubbing the latter optional defamilialism through the market [18].

Familialism has been associated with the reinforcement of both class and gender inequalities in the use or provision of different forms of care, as households must rely on their own resources to meet care needs [6]. However, familialistic policies may impact the traditional gendered division of care roles in a non-uniform way. Supported familialism, with high levels of generosity, can also contribute to the reduction of gender and social inequalities in care by providing additional financial resources for households to purchase care services—thus providing families with an option to defamilialize care through the market—or by financially compensating women for caregiving [4,6,18]. The use of the market nexus to achieve defamilialization, may, however, foster greater gender equality among middle-class families with sufficient financial resources to outsource care, whilst leaving poorer families without that option [19]. The existing evidence points to larger social inequalities favoring the more affluent in the use of formal care in countries with predominantly familialistic care policies [11,12,20]. As regards gender, the available research concurs that higher reliance on the family for the fulfillment of care needs is associated with a higher burden for female carers, specifically wives and daughters [21,22]. Legal obligations to care, rather than cash benefits, seem to be associated with larger gender inequalities among siblings providing high-intensity care [23].

However, some of the evidence on inequalities across different care regimes is based on studies that group countries into clusters according to their degree of familialism/defamilialism [20,24]. While this approach may enhance sample size for empirical purposes, it risks grouping together quite dissimilar countries [25]. The few existing comparative studies have counterposed familialism with defamilialization (i.e., in-kind public provision). These ‘most dissimilar case’ studies attribute outcomes to different public policies that may actually result from the interplay of differences in culture as well as public policies [26]. The policy relevance of the findings of these studies may also be limited, as recent policy developments seem to rely increasingly on different forms of familialism rather than on defamilialization through public services [10], making comparisons within different types of familialism more relevant. Differences between varieties of familialism remain underresearched, especially from the perspective of gender and SEC inequalities within different forms of familialism. This paper seeks to address this gap by comparing two neighboring countries that can be deemed similar in terms of their care culture (i.e., their preferences regarding state and family roles in care), but dissimilar enough in terms of public policies. This ‘most similar case’ design focuses on Austria and Slovenia as neighboring countries with different forms of familialism. Moreover, in choosing these countries, the empirical analysis includes one case (Slovenia) from a region (Eastern Europe) that is underrepresented in both the care regime and inequalities of care literature.

As regards care for older people, Austria and Slovenia share a strong tradition of family values that emphasize the family as the main caregiver [27]. In both countries, carers live in relative proximity to their dependent relatives due to general low housing mobility within the population and the majority of the regions in each country have a similar share (25–30%) of older people living alone [28]. Both countries also have similar demographic aging and health profiles. The population group aged 65–79 represents 14.4%and 15% of the total population for Austria and Slovenia, respectively, while the 80+ group accounts for 4.9% and 5.2%, respectively [29]. Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy at 65 is nearly identical for Austria (20.1 and 7.4, respectively) and Slovenia (20.0 and 7.4, respectively) [30]. They markedly differ, however, in terms of the public care policies in place. Informal carers in Slovenia receive little support in the form of either specialized care services (e.g., respite care) or cash benefits [31,32]. Family members who opt for part-time employment because of their caring responsibilities cannot retain the full level of social security benefits nor do they receive any compensation for lost income, except under specific conditions of the status of family assistant that enables partial or full-time withdrawal from the labor market. The take-up of the latter was at the time of the study however marginal. Children are legally obligated to contribute to the costs of their parent’s care if the latter cannot afford the costs on their own [33]. Slovenia’s care regime is best described as prescribed familialism with an underdeveloped formal care sector [32,34,35]. Data for 2015, show that only 1.1% of the population received formal home care in Slovenia [36].

Austria, on the other hand, has been defined as an example of supported familialism, with the family retaining the role of main care provider, supported by a universal cash benefit (Pflegegeld) provided to dependent older adults, which is usually used to compensate informal family carers [5,37]. In addition, informal carers are entitled to an income-related care leave of up to 3 months and to health and pension insurance if they need to reduce their working time to provide care [38]. As for formal care services at home, the overwhelming majority of which are non-profit, data for 2015 indicate that 32.2%of Pflegegeld beneficiaries receive some form of care services at home, corresponding to 2.3% of the total population [39]. Apart from formal care services, migrant live-in carers (known as ‘24 h carers’) play an important role in the context of long-term care in Austria [40]. Additional means-tested benefits are available for users who rely on self-employed 24-h carers or who employ them directly. Both the development of 24 h carers and services at home by non-profit organizations have provided families in Austria with the option of defamilializing through the market [18]. There is scarce information on inequalities in the use of care in both countries. Still, the existing evidence points to gender inequalities in Austria in both caregiving (share of women among informal carers is 73% [41]) and care receiving (married older women more likely to receive home care services than married older men [42]).

2.3. Determinants of Task Division

At the individual level, several factors have been found to influence the division of tasks between formal and informal carers. Lower care needs and geographic proximity of carers and users are associated with informal care only or kin independence [7], while higher care needs increase the chance of using formal care for specific tasks [7,43]. SEC seems to be positively associated with the use of formal care only and mixed forms of task division [44,45,46,47], particularly the complementation model [8]. The supplementation model, which has been linked to overburdened informal carers or users with very high care needs, seems to be the exception to this as it is more likely to be found amongst individuals with lower SEC [8,48]. When viewed together, this body of evidence points to formal care only and the complementation models as those associated with individuals who enjoy a greater degree of choice, namely those with greater access to economic resources. For informal care only, existing studies show contradictory evidence as to the effect of SEC [7,45,47,49]. Thus, some studies associate this model with low SEC, as a result of financial constraints in accessing formal care, while in other studies the association is non-existent or goes in the opposite direction, possibly as bequest motivations may be stronger in the presence of wealth.

As regards the gender of the carers, male carers are overrepresented in the complementation model, while female carers are linked with the supplementation and informal care only models [7,46]. Overall, daughters are more likely to be carers than sons [23], but in contexts of greater availability of services, children tend to specialize in particular tasks (e.g., home help), regardless of gender (i.e., complementation) [50]. As for the gender of the user, there is pervasive evidence that frail older women are more likely to receive formal care only or mixed forms of care [42,46,51,52].

Reflecting on the existing evidence, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The socio-economic gradient will be steeper in the context of prescribed familialism (Slovenia) than in supported familialism (Austria) (. SEC would be a better predictor of the use of formal care in Slovenia, as the cash-for-care benefit available under-supported familialism enhances the ability of Austrian households to pay for formal care. More specifically to the task division models, socio-economic inequalities are expected to be particularly large for the formal care only and complementation models in Slovenia, as these are the models more closely associated with the ability to choose.

Hypothesis 2.1 (H2.1).

We also hypothesize that supported familialism, which enables households to pay for formal care, is more conducive to a wider distribution of care within families, rendering the gender of adult children (the potential caregivers) less relevant for the type of care tasks model and thus to increased gender equality. A less pronounced association between the gender of adult children (e.g., whether daughters are available) would thus be expected in Austria, particularly in the informal care only, complementation, and supplementation models.. This would be further reinforced by the higher availability of formal care in Austria.

Hypothesis 2.2 (H2.2).

Conversely, if the nature and generosity of the provided support are insufficient to motivate sons to take on additional care tasks, the opposite effect would be observed, whereby the benefits under-supported familialism would create additional incentives for women (i.e., daughters) to care. In this case, we hypothesize that the additional support available in Austria would reinforce the association between having daughters and the probability to receive care from task division models more closely linked with female carers in the literature: informal care only and supplementation models. Given the dearth of guidance from the literature on the expected gender gradient in care-receiving across care regimes, we do not articulate a specific hypothesis for gender inequalities in care-receiving, but nonetheless present the results for these, as well as an exploratory study.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Finally, following the above-cited interplay of gender inequalities with cash benefits, we hypothesize that defamilialization through the market, afforded by the Pflegegeld in Austria, would have a differentiated impact on gender inequalities across socio-economic groups. In other words, we expect that if there is an association between the availability of daughters and informal care only and supplementation models, this association would be most pronounced among the lower SEC groups, particularly in Austria.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

This study uses data from the sixth wave of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), collected in 2015, as it enabled comparison of the two countries, and was done prior to COVID-19 pandemic, which could affect the caring patterns [53]. The sample is restricted to community-dwelling individuals aged 60 and above who reported receiving formal care, informal care or both, during the 12 months prior to the interview and who reported having children. The latter restriction ensures that the sample contains only individuals who could theoretically receive familial informal support, in particular filial informal care. The final sample consisted of 1668 individuals, 916 residing in Austria and 752 in Slovenia.

3.2. Dependent Variable(s)

SHARE includes information on personal care (e.g., dressing, bathing or showering, eating, getting in or out of bed, using the toilet) and practical household help (i.e., help with domestic tasks such as shopping or home repairs, preparing meals, and help with other activities such as medication management) received in the 12 months before the interview. There is also information on help provided with paperwork or legal matters by people outside the household. These were included as household help in the context of this study. It is possible to attribute each of the above types of care tasks to a professional or paid service (formal carers) or to family members residing outside the household, friends, or neighbors (informal carers). With this information, five models of care task division were constructed based on how personal care and household help were distributed between formal and informal carers according to the typology described in Figure 1: informal care (IC) only, informal care specialization, supplementation, complementation, and formal care (FC) only. For example, supplementation refers to where respondents have indicated that they have received whatever type of care tasks (i.e., personal care, household help, or both) always from formal and informal caregivers simultaneously. Complementation, on the other hand, includes cases where users always reported receiving both types of care, either in a completely non-overlapping way (e.g., household help is received from formal carers, but not from informal carers and vice-versa for personal care) or with one care tasks being shared between formal carers and informal carers, while the other is only carried out by formal carers (e.g., household help for the former and personal care for the latter). The dependent variable is thus a categorical variable with five levels, reflecting these mutually exclusive models of task division, which between them cover all possible combinations of task distribution between formal and informal carers.

3.3. Independent Variables

Equivalized household net income was used as the main measure of material resources. Household net income is calculated by aggregating all income sources of all household members, including earnings from work, pensions, and social benefits, as well as income from rents or dividends and interests paid on financial investments. Household net income is adjusted for purchasing power parity and equivalized for household size using the square root scale [54]. Income calculated in this way was then coded by quartiles.

Income provides a measure of readily available resources, which individuals can use to access care, and it is used in both countries to determine the price of care. However, upon retirement, the income of older individuals decreases and the variability of income in this population is significantly reduced [55,56], while wealth remains much more unequally distributed [57]. Older people may thus rely both on their income and their wealth (spending down accumulated assets) to finance costs related to their care needs [58]. Using wealth (i.e., equivalized net worth, which includes all net financial assets and real assets held by household members) and income simultaneously raises the issue of collinearity, as the association between the two is generally strong, especially at the extremes of the distribution. The income wealth quartile correlation matrix per country showed a non-negligible correlation between the two measures (Spearman’s rho Austria = 0.364 Slovenia = 0.274), cautioning about the possible collinearity between income and wealth. Using either measure of material resources produced similar results, as did the inclusion of both variables in the model, therefore only the results of the model with income quartiles are shown.

The gender of the user is defined by a binary variable. Another binary variable assessing whether there is at least one daughter living within a 25 Km radius was constructed as a measure of gendered (i.e., female) availability of adult children to perform informal care. While the sample is already restricted to people with adult children (i.e., for whom at least in theory family carers would be available), this variable distinguishes those with a daughter living close to ascertain whether such closer and gendered availability of a potential family carer are correlated with particular care task models, as suggested by the literature. Household size is used as a proxy for the availability of informal care within the household.

Care needs are represented by three binary variables, indicating whether the care user experiences: (a) one or more limitations in ADLs; (b) one or more limitations in IADLs; (c) cognitive impairment (Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, organic brain syndrome, senility or any other serious memory impairment). In each case, respondents are asked to report only long-standing functional limitations (that lasted or are expected to last more than three months). The age of the care user is coded into three age groups: 60–63, 64–79, and 80 and older.

3.4. Analytical Approach

The prevalence of the various models of task division across countries was analyzed by means of frequency distribution, using a chi-square test to compare the two countries. To further account for confounding factors, multinomial logistic regression was used to analyze how task division is influenced by the various determinants. The differences between the two countries and between the income quartiles within the two countries; the differences between gender of the care user and potential informal carer within the two countries; and the differences between the latter two across income quartiles within the two countries were analyzed using average marginal effects (AMEs). Reporting AMEs allows us to circumvent the problem of unobserved heterogeneity in logistic regression and estimate the effect differences between samples [59]. Furthermore, AMEs enable the reporting of results for all five levels of the dependent variable and thus avoid the selection of a random reference category. Small Hsiao tests for the independence of irrelevant alternatives and sensitivity analyses using similar specifications with multinomial probit confirm the robustness of the results. We used Z-tests to check whether the estimated AMEs differed significantly between groups defined across income quartiles, wealth quartiles, and gender. All statistical analyses were carried out using the Stata 15.0 statistical package (StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LLC).

4. Results

Care services were used by 36.5% of the respondents in the Austrian sample and 18.7% of the respondents in the Slovenian sample (chi-square statistic: 29.6 p-value < 0.001). Informal care use is widespread in both countries, as 89.9% and 95.9% of Austrian and Slovenian respondents respectively, reported using it (chi-square statistic: 6.2, p-value < 0.01). Other descriptive statistics of the joint sample are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the joint analytical sample, means, and percentages for each model of task division.

The distribution of the models of care task division within income quartiles and the gender variables per country are displayed in Table 2. We found only small differences in the prevalence of the IC only, IC specialization, and complementation models across income quartiles in either Austria or Slovenia. The FC-only model, however, is clearly more prevalent in the uppermost income quartile in both countries. The supplementation model is also heterogeneously distributed across income quartiles, but these differences are not monotonous: There is a higher prevalence of this care tasks model among the first income quartile in Austria and among the second income quartile in Slovenia. Regarding the gender of the care user, there are very few differences in the prevalence of the different care task models in Slovenia, unlike in Austria. For the latter, the table of frequencies indicates gender differences in the use of IC only (more prevalent among male users) and the supplementation model (more prevalent among female users). The IC only is more prevalent among those with at least one daughter living in the vicinity of Austria, while the complementation model has a higher prevalence among those with no closely residing daughters.

Table 2.

Distribution of models of task division within income quartiles and gender per country (row percentages).

4.1. Task Division between Countries

The prevalence of the various models of task division per country is reported in Table 3. The prevailing model of task division in both countries was IC only, especially in Slovenia, where 81% of the care users reported this model (compared to 64% in Austria). Supplementation was the second most prevalent model of task division in both Austria (16%) and Slovenia (9%). FC only was reported by 10% of the users in Austria, as opposed to only 5% in Slovenia. Complementation was the least prevalent model of task specialization in Slovenia (2%), while 6% of users in Austria reported this model. Finally, the IC specialization model was the least present in the Austrian subsample (3%), and its prevalence was also low in Slovenia (2%). Across all models of task division, except IC only, household help was mostly provided by formal carers, while informal carers mostly provided personal care (detailed distribution of tasks within models of care task division and countries is available upon request from the authors).

Table 3.

Distribution (in percentage) of models of task division within country and AMEs for country per model of task division.

Chi-square statistic for distribution of task division within country (percentages): 67.7 (p-value < 0.001).

AMEs calculated from a multinomial regression model controlling for income, ADLs and IADLs, cognitive impairment, education, age, gender, household size, and geographical proximity of daughters. Calibrated cross-sectional individual weights used for calculating AMEs. Sample sizes presented in parenthesis are used in all regression analyses.

Samples presented here are used in all regression analyses.

Table 3 also shows the AME for Slovenia (with Austria as the reference category) on the probability of receiving each model of task division. After controlling for differences in the several determinants of task division, statistically significant country differences persisted in all models of task division, except IC specialization. Complementation, supplementation, and FC only are all more likely to be found in Austria than in Slovenia, while IC only is more likely to be found in Slovenia.

4.2. Material Resources and Care Task Division by Country

Table 4 shows the AMEs for income within each country (i.e., first differences), which allows for a comparison of inequalities within countries. Income was positively associated with the probability to use FC only in Austria, while in Slovenia, this association was only statistically significant for the fourth income quartile. The inverse was observed for IC only. For this care tasks model, there was a clear negative association with income in Slovenia, while in Austria, this strong negative association was only significant for the fourth quartile. The mixed forms of care task division (i.e., where formal and informal care are used) showed only limited evidence of inequalities based on economic resources in either Austria or Slovenia. For the complementation model in particular—associated with higher ability to choose—there was no evidence of inequalities in either country. The direction of the association between income and the supplementation model was opposite between Austria and Slovenia, but the AME was only statistically significant for the second income quartile in both countries.

Table 4.

AMEs for income quartiles within country.

Based on a multinomial regression model controlling for ADLs and IADLs, cognitive impairment, education, age, gender, household size, and geographical proximity of daughters. Weighted results. First income quartile in each country is the reference category. Calibrated cross-sectional individual weights used.

4.3. Gender and Care task Division by Country

Regarding possible gender inequalities in care task division, Table 5 reports AMEs for the variable taken as a proxy for the gender of potential family carers and the gender of the care user within countries. Having at least one daughter living nearby was negatively associated with the complementation model in both countries, while it increased the probability of receiving informal care only (i.e., IC only) in Austria, but not in Slovenia. As for FC only, the impact of the geographical proximity of daughters was positive and significant in Slovenia, but not in Austria.

Table 5.

AMEs for gender variables within country.

Based on a multinomial regression model controlling for income, ADLs and IADLs, cognitive impairment, education, age, and household size. Weighted results. For each country, male users and not having a daughter living within 25 Km are the reference categories respectively. Calibrated cross-sectional individual weights used.

With respect to the gender of the care user, this variable only had an impact in Austria. In comparison with older male users, women were more likely to receive care from their informal carers that are supplemented by care services and less likely to receive IC only. Where significant, the AMEs for the gender of the care users were, however, of higher magnitude than those reported for the geographic proximity of daughters, suggesting a greater impact of the former in care task division.

4.4. Intersection of Gender, Income, and Care Task Division by Country

Table 6 shows the AMEs for the interaction of the gender and income variables (i.e., second differences), estimated separately for each country. While the positive association of geographic proximity of daughters with IC only for Austria was positive (Table 5), this overall effect hid important differences across income quartiles as described in Table 6. It is not present at all in the lower income quartile, and it is actually negative for those in the uppermost income quartile. This negative association for the fourth income quartile also held for Slovenia. In Slovenia, the overall positive impact of daughters living nearby on the exclusive use of formal care (i.e., FC only) seems to be mostly driven by those in the most affluent income quartile. In both countries, the negative association of daughters living nearby with the complementation care task model seems to be confined to those in the first income quartile.

Table 6.

AMEs for interaction terms between gender variables and income quartiles within country.

Based on a multinomial regression model controlling for ADLs and IADLs, cognitive impairment, education, age, and household size. Weighted results. For each country and income quartile, male users, and not having a daughter living within 25 Km are the reference categories respectively. Calibrated cross-sectional individual weights used.

In Austria, the previously reported negative association between being a female user and the IC-only model (Table 5) was restricted to the two upper-income quartiles (Table 6). The positive association between the gender of the care user and the supplementation model, on the other hand, was rather uniformly distributed across income quartiles in Austria. Being a female user increased the probability of reporting the complementation model for Austria and Slovenia, but in both cases only for those at the top of the income distribution. For Slovenia, only among the highest income users did women have a lower probability of receiving FC only.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to explore how task division in care for older people may differ between two countries defined along different forms of familialism—prescribed familialism (Slovenia) and supported familialism (Austria)—and particularly how socio-economic condition (SEC) and gender are linked to task division across these forms of familialism. We hypothesized that the socio-economic gradient would be steeper for prescribed familialism (Slovenia) than for supported familialism (Austria) (H1). For gender differences, there were two competing hypotheses: Supported familialism could allow for a wider distribution of care within families and render the gender of adult children less relevant for care task division, in effect diminishing gender inequalities (H2.1); or the additional support could reinforce gender inequalities in supported familialism by associating some types of task division with daughters (H2.2). Finally, the interplay of gender and SEC inequalities was also tested, by analyzing whether the provision of informal care only and supplementation model would be associated with the availability of daughters only for the lower SEC groups in supported familialism (H3).

Regarding the socio-economic gradient, the results did not fully confirm Hypothesis 1 above. SEC did not have a significant impact on the complementation model nor on other mixed models of task division in Slovenia. FC only was positively associated with income in Slovenia, but only for the very affluent, and this association was arguably even greater in Austria. Slovenia’s model of prescribed familialism includes the legal obligation of children to contribute to their parents’ costs of home care, while access to home care is means-tested. Poorer households may thus be targeted to receive publicly-funded care, particularly in the event of high needs [60]. This could explain the lack of SEC gradient in the mixed models of care division, which were correlated with higher need, and the lower than expected SEC gradient in FC only in Slovenia. For Austria, however, the SEC gradient for FC only was quite pronounced, despite the Pflegegeld and higher availability of care services. One possible driver for these SEC differences in Austria could be the option to outsource care to 24-h carers; an option of defamilialization through the market that has been positively associated with more affluent users of cash benefits in similar contexts [61]. It is worth bearing in mind that SEC here refers only to economic resources (income) and not to education, even though the two are correlated.

Where the SEC gradient was indeed steeper for Slovenia, it was for IC only. It could have been expected that the legal obligation to contribute to their parents’ costs of home care could incentivize more affluent families to replace care services for informal care, to circumvent such payment obligations. This was not confirmed by the data and there are several possible reasons for this. First, equity release to pay for residential care seems to be an accepted potential option in Slovenia [33]. In addition, intergenerational cohabitation is known to be concentrated among the more affluent [62] and this type of living arrangement is more predominant in Slovenia. It is possible that informal care provided within the household is higher among higher-income families and therefore not captured by the IC-only model as currently defined—due to data constraints, the IC-only model includes informal care received from outside the household and excludes care provided by members of the same household. The country differences in IC only could also be attributed to the greater leeway to outsource care afforded by the Pflegegeld in Austria. These results were robust to the measure of SEC used. The evidence of pro-rich inequalities in FC only and the negative association of IC only with SEC are thus in line with findings from other studies on the use of care [11,12,24].

Regarding gender inequalities in caregiving, these were more evident in Austria than in Slovenia. Having a daughter living no farther than 25 km increased the chances of receiving IC only in Austria alone, while greatly reducing the chances of the complementation model in both countries. This is in line with other studies on gendered task division [7,46]. The notable exception to traditional gender roles was found in Slovenia, where the proximity of daughters was positively associated with FC only. Findings thus support the proposition that supported familialism may reinforce gender inequalities [6], lending credence to Hypothesis H2.2 rather than Hypothesis H2.1. Regarding care receiving, the literature offers little guidance as to the expected direction of inequalities and underlying causal pathways. Results did show that older women in Austria were more likely to receive care in the supplementation model, which in turn is associated with daughters as potential informal carers. This association of mothers (users) and daughters (carers) seems to reflect closer bonds and shared preferences between the two [63]. Similarly, older women in Austria were less likely to receive IC only in line with findings from at least another study [42].

The gender differences across income groups (H3) indicate the different ability of families to defamilialize through the market according to their SEC, albeit with limited country differences, except for IC only. Results thus only partially give credence to Hypothesis H3. The proximity of daughters was positively associated with IC only but only for the middle-income quartiles in Austria. For higher-income families both in Austria and Slovenia, this association with IC only was negative. This could indicate a greater ability by higher income families to defamilialize through the market [6,19]. Indeed, for Slovenia, the proximity of daughters was also positively associated with exclusive use of formal care only in the uppermost income quartile. The complementation of tasks—which is associated with greater choice and with male carers [7,46]—was less likely to take place when daughters lived in proximity. This effect, however, only held for the lower income quartile and again for both countries. For female users, results showed that they were less likely to receive IC only among the two higher income quartiles in Austria only, even after controlling for living arrangements and care needs. Again, this could indicate a greater ability by higher income families to defamilialize at least part of care (i.e., by not relying exclusively on informal care).

6. Conclusions

This study contributes in two novel ways to the literature on the use of different forms of care. First, it carries out a comparative exploration of the differences in care task division between countries, which was until now absent from this strand of literature [8]. Secondly, it provides a much deeper understanding of socio-economic and gender inequalities in care by expanding the dichotomy between formal and informal care or carers [64,65] to include mixed models of care and considering inequalities in the context of care tasks.

These findings have several policy implications. Despite or perhaps because of its generosity, the supported familialism model in place in Austria did not alleviate gender inequalities in both caregiving and care provision, in comparison with the prescribed familialism prevailing in Slovenia. This raises questions regarding whether generous cash transfers have a sizeable impact on gender inequalities within the variations of familialism. At the same time, the ability of families to defamilialize through the market was indeed associated with SEC, but differences between the two countries were smaller than expected. The option to outsource care to the market may thus be outside the possibilities of lower-income households and require more targeted transfers. Although mixed forms of care as a whole represented a minority of users, they were overwhelmingly concentrated in the older age users and those with higher and more diverse care needs. Aging in place and delayed institutionalization is therefore likely to be best achieved not by exclusive models of task division (kin or formal care provider independence), but through a combination of different types of care providers.

There are a number of caveats to consider in this study. First of all, the sample size for the IC specialization and complementation models in Slovenia is small. Alternative possibilities to increase the sample size, such as merging consecutive waves of SHARE, were not feasible given the lack of absolute comparability of questions across waves. This may limit the statistical significance of results for these models for Slovenia, even though it is unlikely that the study has falsely identified significant effects, since a small sample size increases the probability of a type II error (false negative). The findings should nonetheless be considered exploratory for these models. The employed typology considers only informal care provided from outside the household, thus leaving aside spousal or filial care provided within the household. This is likely to underrepresent the contribution of informal care where intergenerational cohabitation is relevant. To address this, all estimations have household size as a control variable. As with most studies on the use of care among older individuals, there is potential for self-selection due to mortality and institutionalization [66]. Both risks disproportionately affect people of low SEC and may thus impact the measurement of SEC inequalities. Institutionalization may also account for a higher prevalence of IC only in Slovenia, as this country has a higher share of older people cared for in institutions (5% of 65 + are in institutional care in Slovenia, a proportion approximately twice as high as in Austria [67]). Finally, the task division models used in this study do not account for care intensity. It is possible that mixed care models of task division correspond to lower the intensity of care by informal carers, even in the cases where informal carers provide both home help and personal care. This could not, however, be established with the data used in this study.

To conclude, this exploratory study makes the case for analyzing gender and SEC inequalities in care through the lens of care task division, particularly across different forms of familialism. Findings suggest that supported familialism, even when generous, is associated with a traditional gendered task division. Besides this, we find limited evidence of variability in the SEC gradient of task division between strands of familialism, but pervasive signs of within-country SEC inequalities in the division of tasks between formal and informal carers. This study is based on the example of two countries. However, given the preponderance of different strands of familialism across Europe and in recent policy developments, its findings have a broader relevance within the policy and research discussions around long-term care reforms and development.

Author Contributions

All authors share the responsibility for the conception and design of the study and all authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, and its revision. R.R. and S.I. are the main responsible for the interpretation of the data and drafting of the manuscript. S.I. carried out the statistical analyses, with support from R.R. and A.S., M.F.H. and V.H. provided the description of the Slovenian welfare context, helped drafting the theoretical context and contributed to revisions of the text. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received funding from the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS), Grant Agreement [J5-8235], and from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), Grant Agreement [I3422-G29].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

This paper uses data from SHARE Wave 6 (DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w6.700), see Börsch-Supan et al. (2013) for methodological details [53]. The SHARE data collection has been funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812), FP7 (SHARE-PREP: GA N°211909, SHARE-LEAP: GA N°227822, SHARE M4: GA N°261982) and Horizon 2020 (SHARE-DEV3: GA N°676536, SERISS: GA N°654221) and by DG Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion. Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064, HHSN271201300071C), and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors confirm that they have no conflict of interest concerning the research reported in this study.

References

- Schulz, R.; Sherwood, P.R. Physical and Mental Health Effects of Family Caregiving. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2008, 44, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, F.; Charles, S.; Hulme, C. Who will care? Employment participation and willingness to supply informal care. J. Health Econ. 2010, 29, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, R.; Huber, M.; Lamura, G. Facts and Figures on Healthy Ageing and Long-Term Care–Europe and North America; European Centre: Vienna, Austria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Leitner, S. Varieties of Familialism. Eur. Soc. 2003, 5, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettio, F.; Plantenga, J. Comparing Care Regimes in Europe. Fem. Econ. 2004, 10, 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraceno, C. Varieties of familialism: Comparing Four Southern European and East Asian Welfare Regimes. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2016, 26, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noelker, L.S.; Bass, D.M. Home care for elderly persons: Linkages between formal and informal caregivers. J. Gerontol. Soc. Sci. 1989, 44, S63–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, T.M.; Broese van Groenou, M.I.; Boer, A.H.; Deeg, D.J.H. Individual determinants of task division in older adults’ mixed care networks. Health Soc. Care Community 2014, 22, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlebec, V.; Filipovič Hrast, M. Influence of Contextual and Organisational Factors on Combining Informal and Formal Care for Older People: Slovenian Case. Res. Ageing Soc. Policy 2016, 4, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranci, C.; Pavolini, E. Not all that glitters is gold: Long-term care reforms in the last two decades in Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2015, 25, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertini, M.; Pavolini, E. Unequal inequalities: The stratification of the use of formal care among older Europeans. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2017, 72, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodrigues, R.; Ilinca, S.; Schmidt, A. Income-rich and wealth-poor? The impact of measures of socio-economic status in the analysis of the distribution of long-term care use among older people. Health Econ. 2018, 27, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantor, M.H. Life space and the social support system of the inner city elderly of New York. Gerontology 1975, 15, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelman, P. The impact of community care to the home-bound elderly on provision of informal care. Gerontology 1986, 26, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwak, E. Helping the Elderly: The Complimentary Roles of Informal Networks and Formal Systems; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Green, V.L. Substitution between formally and informally provided care for the impaired elderly in the community. Med. Care 1983, 21, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraceno, C.; Keck, W. Can We Identify Intergenerational Policy Regimes in Europe? Eur. Soc. 2010, 12, 675–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bihan, B.; Da Roit, B.; Sopadzhiyan, A. The turn to optional familialism through the market: Long-term care, cash-for-care, and caregiving policies in Europe. Soc. Policy Adm. 2019, 53, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rummery, K. A Comparative Discussion of the Gendered Implications of Cash-for-Care Schemes: Markets, Independence and Social Citizenship in Crisis? Soc. Policy Adm. 2009, 43, 634–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasa, S.; Billingsley, S. Personal and household caregiving from adult children to parents and social stratification. In Families, Ageing and Social Policy. Intergenerational Solidarity in European Welfare States; Saraceno, C., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2008; pp. 123–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsang, E. Does Informal Care from Children to their Elderly Parents Substitute for Formal Care in Europe? J. Health Econ. 2009, 28, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberkern, K.; Schmid, T.; Syzdlik, M. Gender differences in intergenerational care in European welfare states. Ageing Soc. 2015, 35, 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmid, T.; Brandt, M.; Haberkern, K. Gendered support to older parents: Do welfare states matter? Eur. J. Ageing 2012, 9, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carrieri, V.; Di Novi, C.; Orso, C.E. Home Sweet Home? Public Financing and Inequalities in the Use of Home Care Services in Europe. Fisc. Stud. 2017, 38, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambra, C. Cash Versus Services: ‘Worlds of Welfare’ and the Decommodification of Cash Benefits and Health Care Services. J. Soc. Policy 2005, 34, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pfau-Effinger, B. Culture and Welfare State Policies: Reflections on a Complex Interrelation. J. Soc. Policy 2005, 34, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eurobarometer. Health and long-term care in the European Union. In Special Eurobarometer 283; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2007; pp. 1–247. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. People in the EU. Who are We and How Do we Live. Eurostat Statistical Books; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Population Statistics on 1 January by Age and Sex. Eurostat. 2019. Available online: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=demo_pjan&lang=en (accessed on 25 July 2019).

- Eurostat. Healthy Life Years (Since 2004). Eurostat. 2020. Available online: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Courtin, E.; Jemiai, N.; Mossialos, E. Mapping support policies for informal carers across the European Union. Health Policy 2014, 118, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hlebec, V.; Srakar, A.; Majcen, B. Care for the elderly in Slovenia: A combination of informal and formal care. Rev. Za Soc. Polit. 2016, 23, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandič, S. Housing for care: A response to the post-transitional old-age gap? J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2016, 26, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hlebec, V.; Nagode, M.; Filipovič Hrast, M. Care for older people between state and family: Care patterns among social home care users. Teor. Praksa 2014, 51, 886–903. [Google Scholar]

- Hlebec, V.; Rakar, T. Ageing policies in Slovenia: Before and after austerity. In Selected Contemporary Challenges of Ageing Policy, (Czech-Polish-Slovak Studies in Andragogy and Social Gerontology, Part 7); Tomczyk, Ł., Klimczuk, A., Eds.; Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny w Krakowie: Krakow, Poland, 2017; pp. 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Černič, I. Celotni Izdatki za Dolgotrajno Oskrbo v 2015 (489 Milijonov EUR) Višji Kot v 2014. Statistical Office of Republic of Slovenia, Ljubljana, Republika Slovenija. 2017. Available online: https://www.stat.si/StatWeb/News/Index/7116 (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Österle, A.; Bauer, G. Home care in Austria. In LIVINDHOME: Living Independently at Home, Reforms in Home Care in 9 European Countries; Rostgaard, T., Ed.; SFI-Danish National Centre for Social Research: Copenhage, Denmark, 2011; pp. 117–138. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, A.E.; Fuchs, M.; Rodrigues, R. Juggling Family and Work–Leaves from Work to Care Informally for Frail or Sick Family Members—An International Perspective; Policy Brief of the European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research 9/2016; European Centre: Vienna, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- BMASK–Bundesministerium für Arbeit, Soziales und Konsumentenschutz. Sozialbericht. Sozialpolitische Entwicklungen und Maßnahmen 2015–2016. In Sozialpolitische Analysen; BMASK: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Österle, A.; Bauer, G. Home care in Austria: The interplay of family orientation, cash-for-care and migrant care. Health Soc. Care Community 2012, 20, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagl-Cupal, M.; Kolland, F.; Zartler, U.; Mayer, H.; Bittner, M.; Koller, M.; Parisot, V.; Stöhr, D. Angehörigenpflege in Österreich Einsicht in die Situation Pflegender Angehöriger und in Die Entwicklung Informeller Pflegenetzwerke (engl. Caring for Relatives in Austria Insight into the Situation of Caring Relatives and the Development of Informal Care Networks); Bundesministeriums Arbeit, Soziales, Gesundheit und Konsumentenschutz: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, A.E. Older Persons’ Views on Using Cash-for-Care Allowances at the Crossroads of Gender, Socio-economic Status and Care Needs in Vienna. Soc. Policy Adm. 2017, 52, 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, G.; Sundström, G.; Dehlin, O.; Hagberg, B. Formal support, mental disorders and personal characteristics: A 25-year follow-up study of a total cohort of older people. Health Soc. Care Community 2003, 11, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kemper, P. The use of formal and informal home care by the disabled elderly. Health Serv. Res. 1992, 27, 421–451. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prieto, C.V.; Jiménez-Martín, S.; García-Gómez, P. Trade-off entre cuidados formales e informales en Europa. Gac. Sanit. 2011, 25, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paraponaris, A.; Bérengère, D.; Verger, P. Formal and informal care for disabled elderly living in the community: An appraisal of French care composition and costs. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2012, 13, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, R.; Ilinca, S.; Schmidt, A. Analysing Equity in the Use of Long-Term Care in Europe. Research Note 9/2014 Social Situation Monitor. European Commission. 2014. Available online: https://www.euro.centre.org/downloads/detail/1515 (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Scott, J.P.; Roberto, K.A. Use of informal and formal support networks by rural elderly poor. Gerontology 1985, 25, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwin, H.; Attias-Donfut, C. The inter-relationship between formal and informal care: A study in France and Israel. Ageing Soc. 2009, 29, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brandt, M.; Haberkern, K.; Szydlik, M. Intergenerational Help and Care in Europe. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 25, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Portrait, F.; Lindeboom, M.; Deeg, D. The use of long-term care services by the Dutch elderly. Health Econ. 2000, 9, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.J.; Kabeto, M.; Langa, K.M. Gender Disparities in the Receipt of Home Care for Elderly People with Disability in the United States. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2000, 284, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börsch-Supan, A. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 6. Release Version: 6.1.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. 2018. Available online: http://www.share-project.org/data-documentation/waves-overview/wave-6.html (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- OECD. OECD Framework for Statistics on the Distribution of Household Income, Consumption and Wealth; OECD: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Allin, S.; Masseria, C.; Mossialos, E. Measuring Socioeconomic Differences in Use of Health Care Services by Wealth Versus by Income. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 1849–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubbin, C.; Pollack, C.; Flaherty, B.; Hayward, M.; Sania, A.; Vallone, D.; Braveman, P. Assessing Alternative Measures of Wealth in Health Research. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, M.; Murtin, F. The Relationship Between Income and Wealth Inequality: Evidence from the New OECD Wealth Distribution Database. In Proceedings of the IARIW Sessions at the 2015 World Statistics Conference Sponsored by the International Statistical Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 26–31 July 2015; OECD: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.W. Income and Wealth of Older Adults Needing Long-Term Services and Supports. In Testimony to the Commission on Long-Term Care; The Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mood, C. Logistic Regression: Why We Cannot Do What We Think We Can Do, and What We Can Do About It. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 26, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muir, T. Measuring Social Protection for Long-Term Care; OECD Health Working Papers, No. 93; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barbabella, F.; Chiatti, C.; Rimland, J.M.; Melchiorre, M.G.; Lamura, G.; Lattanzio, F. Up-Tech Research Group. Socioeconomic Predictors of the Employment of Migrant Care Workers by Italian Families Assisting Older Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: Evidence from the Up-Tech Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 514–525. [Google Scholar]

- Jong Gierveld, J.; Dykstra, P.A.; Schenk, N. Living arrangements, intergenerational support types and older adult loneliness in Eastern and Western Europe. Demogr. Res. 2012, 27, 167–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suitor, J.J.; Pillemer, K. Choosing daughters: Exploring why mothers favor adult daughters over sons. Sociol. Perspect. 2006, 49, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, P.; Challis, D.; Hallberg, I.R.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Saks, K.; Vellas, B.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Sauerland, D. RightTimePlaceCare Consortium. Informal and formal care: Substitutes or complements in care for people with dementia? Empirical evidence for 8 European countries. Health Policy 2017, 121, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambotte, D.; Donder, L.; Van Regenmortel, S.; Fret, B.; Dury, S.; Smetcoren, A.; Dierckx, E.; Witte, N.; Verté, D.; Kardolcthe, M.J. D-SCOPE Consortium. Frailty differences in older adults’ use of informal and formal care. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 79, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Ourti, T. Socio-economic inequality in ill-health amongst the elderly. Should one use current income or permanent income? J. Health Econ. 2003, 22, 187–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagode, M.; Zver, E.; Marn, S.; Jacović, A.; Dominkuš, D. Dolgotrajna Oskrba-Uporaba Mednarodne Definicije v Sloveniji (Engl. Long-term Care–Usage of International Definition in Slovenia); Working Paper No. 2/2014, XXIII.; UMAR/IMAD: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).