Highlights

- There are seven design practises that are emerging in higher educational practises across The Netherlands and Western Europe to connect universities with local transition challenges for more regenerative sustainable futures;

- The Regenerative Higher Education Design Practises Tool has the potential to be used to (re)design education to connect with sustainability transitions;

- Podcasting could be used as a form of qualitative inquiry within sustainability- and educational sciences.

Abstract

Universities have the potential, and the responsibility, to take on more ecological and relational approaches to facilitating learning-based change in times of interconnected socioecological crises. Signs for a transition towards these more regenerative approaches of higher education (RHE) that include more place-based, ecological, and relational, ways of educating can already be found in niches across Europe (see for example the proliferation of education-based living labs, field labs, challenge labs). In this paper, the results of a podcast-based inquiry into the design practises and barriers to enacting such forms of RHE are shown. This study revealed seven educational practises that occurred across the innovation niches. It is important to note that these practises are enacted in different ways, or are locally nested in unique expressions; for example, while the ‘practise’ of cultivating personal transformations was represented across the included cases, the way these transformations were cultivated were unique expressions of each context. These RHE-design practises are derived from twenty-seven narrative-based podcasts as interviews recorded in the April through June 2021 period. The resulting podcast (The Regenerative Education Podcast) was published on all major streaming platforms in October 2021 and included 21 participants active in Dutch universities, 1 in Sweden, 1 in Germany, 1 in France, and 3 primarily online. Each episode engages with a leading practitioner, professor, teacher, and/or activist that is trying to connect their educational practice to making the world a more equitable, sustainable, and regenerative place. The episodes ranged from 30 to 70 min in total length and included both English (14) and Dutch (12) interviews. These episodes were analysed through transition mapping a method based on story analysis and transition design. The results include seven design practises such as cultivating personal transformations, nurturing ecosystems of support, and tackling relevant and urgent transition challenges, as well as a preliminary design tool that educational teams can use together with students and local agents in (re)designing their own RHE to connect their educational praxis with transition challenges.

1. Introduction

The severity of the climate crisis, as well as crises related to social (in)justice and loss of biodiversity, is undeniable [1,2,3]. It is becoming clearer that even reaching the Paris accords of 1.5c global warming is increasingly unlikely, which poses a severe long-term threat to planetary life’s ability to thrive. To prevent this systemic failure, we must transition toward more sustainability-oriented futures where ecosocial systems are designed to balance human activity and natural ecosystem integrity [4,5,6,7]. In other words, we must transform toward more sustainable realities. These sustainability transitions (STs) consist of multi-level, large-scale transformations of society, typically over long timescales. The need for STs has led to the emergence of transition studies [8,9], as well as related fields such as transition design [10]. STs typically challenge, disrupt, and ultimately replace previous paradigms. To restore the human presence on Earth, this involves a transition toward regenerative sustainability [6,11,12], a sustainability that actively aims to restore or heal a damaged world and allows it to evolve and thrive [13,14].

Universities have increasingly engaged in scholarship about transitions, see, for example, the flourishing literature on transitions of all kinds, such as a transition towards a circular society [5,15,16], a society powered by renewable energy [17], transitions in fashion [18,19], foods [20], and health [21]. The importance of learning as a catalyst for change in transitions is frequently mentioned (e.g., [9,22]), but has largely remained outside the field of educational sciences. In other words, the transitional gaze of higher education itself—one that challenges the underlying assumptions, values, dynamics, structures, and perspectives from which long-term systemic unsustainability emerges—remains largely unexplored in the context of educational practise. Of course, there are exceptions, a notable one being the whole-school approach to sustainability [23,24].

The call for universities to engage with STs, as well as sustainability more generally, is increasing in practise (e.g., [8]). We propose that a university that takes sustainability transitions seriously, ought to include an epistemological gaze on her own approaches to educating [25]. This ought to include a rethinking, and more importantly, a redoing, of educational structures, practises, and policies inspired by a regenerative perspective (e.g., [4,8]). Few, if any, universities have fully embraced such an internal transitional gaze. As a result, there is little clarity about what such educational transitions could entail. It is our contention that this is one of the reasons that sustainability in higher education remains locked in innovation niches. In this study, we interview 27 emerging and experienced scholar-practitioners who are rethinking and redoing their educational practises to connect with STs in the places near and within their universities with the intention of actively participating in making more sustainable futures a reality. The authors mirror their ideas to the concept of Regenerative Higher Education (RHE) (e.g., [26,27]), which at its core aims to connect university education with transition challenges in ways that are conducive to personal and planetary health, where learning is oriented towards redirecting systems that are transgressive of socioecological boundaries [28,29]. Through the use of transition mapping, we engage with these emerging experiences from a transitional lens, highlighting leverage points and places within higher education where systemic change towards more regenerative sustainability can be realized [30]. The main research questions are as follows:

- What are the design practises of educators actively moving towards RHE in (Western) Europe that connect with STs?

- What systemic barriers and drivers are experienced when engaging with these practises?

- What personal barriers and drivers are experienced when engaging with these practises?

The Emerging Transition towards RHE

Our study is grounded in the idea of RHE, which we consider to be an ecological approach to education that connects with sustainability transitions locally with the intention of contributing toward more sustainable futures and helps prepare students to navigate the complexities of contributing to such futures [31,32]. This puts the focus of RHE within the discourse on the ecological university as an entangled part of society with a clear moral responsibility to contribute to healing human relationships with each other and the environment [25,33,34]. RHE does this by designing and enacting education with the aim of engaging students in healing ways with STs [35,36], where healing is seen from a salutogenic perspective [6] in the (re)creation of the conditions conducive to generating more resilient futures that can unfold within the carrying capacity of the Earth.

RHE leaves from the following assumptions: (1) that STs and realizing more sustainable realities are required, (2) that higher education can play a role in facilitating these futures to become reality and (3) that there is educational value in doing so. These assumptions are in line with scholarship in the field of philosophy of education, for example, the latest works of [33,37]. As well as calls from leading scholars in sustainability and higher education for transformative change like [38]. We suggest that such engagement could result in further qualification, subjectification, and socialisation towards more life-affirming self-realization [37] and also make universities more meaningful for a healthy planet [8,39]. From this ecological perspective, universities could act as a form of societal virtual reality [40] or as a societal playground to learn from alternative futures to inform our actions today. In practise, this emerging approach is performed by connecting to local communities outside of the university, often in the form of (living) lab-based approaches to education [41,42,43,44]. Within these ecological constellations, participatory approaches with the intent of creating intentional change, such as systemic co-design [45] or transgressive action research [46], are generally used. To do so, however, requires moving toward seeing the profound wealth of the place in which the university is embedded as a rich basis for the curriculum [47,48]. It is not at all clear that universities could fulfil such a role. See, for example, [4,47]. This is a challenge to some who believe that education can be somehow neutral or ought to be limited to not ‘being activistic’ [4] or ‘on the quaint belief that what occurs in educational institutions must be uncontaminated by contact with the affairs of the world and that we have no business objecting to how that world does its business’ [47].

Universities are already ecologically entangled. What may change by embracing RHE is that the normativity of regeneration results in entanglements that may not always be perceived as positive by the dominant power structure. As there may be conflicting interests across generations and or species, part of the purpose of ecological universities could precisely be to make those tensions explicit. To press where it hurts to incite transgression in the broader innovation ecosystem can be considered an (educational) act of service towards such sustainable futures.

From this ‘pressing where it hurts perspective’ that is part of the core of RHE, we follow [46] arguments that the educational task for RHE is more akin to a gardener that tends to and cares for (designs and enacts) the conditions conducive for learners to flourish. Previously, we started building a cartography based on the literature on educational design qualities for a regenerative education [32]; however, a lack of empirical validation remained. With this study, we aim to contribute to this empirical gap in the literature by exploring how nascent and emerging forms of RHE are already being enacted in practise. While not all of the interviewees explicitly identify with RHE already, it is our contention that each of the cases has the potential to become RHE. The interviewees expressed a commitment toward engaging with education as healing (albeit at different systemic levels). Through engagement with their experiences from a transitional lens inspired by an RHE reading, much can be learned for the future design and systemic changes required for RHE through engagement with these emerging innovation niches.

2. Methods

2.1. Podcasting as Qualitative Inquiry

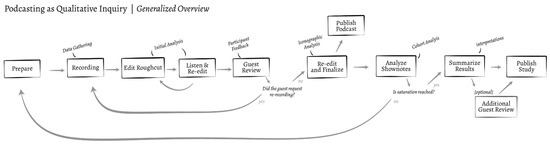

Podcasts have been increasing in popularity for a number of decades now and this popularity is projected to increase further by up to 25–30% annually [49]. Inspired by this popularity, the potential of podcasts as a method, particularly in ethnographic research, has been explored by a variety of scholars (e.g., [50,51,52]). Reasons for these explorations include the following: (1) increased accessibility of research [53,54], (2) inclusion of more non-formal data (sub)cultures [51], (3) and as a geographic research tool [55]. A relatively large subset of podcast-based research includes the usage of podcasts as pedagogical-didactical tools (e.g., [56,57]). These uses of podcast-based inquiry have so far been partial (e.g., using existing podcasts as data or creating podcasts as an output of research). Podcast-based inquiry (see Figure 1) with the intention of simultaneously gathering data and creating output was not identified in the literature.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of podcasting as qualitative inquiry.

To engage with podcasting as a form of data and output generation, we follow the perspective posited by [58] that podcasting sits ‘in-between entertainment and education’ and move beyond that to argue that podcasting, as a creative research method (see [59]), holds the potential to blur the lines or be in the in-between space of data, research, entertainment, communication, and education. As such, podcasting could be used throughout the research process including for data gathering, analysis, and as an accessible form of output for (public) engagement. The use of podcast-based inquiry also proposes several unique benefits for participants (called guests from now on), as it gives them a platform to share their experiences and stories of their alternative practises and perspectives on higher education, and in doing so creating a digital artefact that can be available for use (e.g., didactically, for tenure/promotion, or to share their vision) in perpetuity. To do this, it is however important to engage with the process in a co-constructed manner, seeing the method more as a conversation in which information is co-created instead of extracted [59,60]. This co-constructed perspective aligns with the relational paradigm of sustainability that also informs RHE [61,62] and was highlighted by numerous guests during or after the recording as a sense of reciprocity. For example, one guest posited that their experience felt more like a genuine conversation than previous interviews. Indeed, the potential of podcasting to act simultaneously as data generation and output tool was demonstrated by the engagement of both the public and the guests in the episodes. Several of the guests provided valuable feedback on their own episodes as well as episodes from other guests. As well as actively sharing the episodes (the podcast has been downloaded more than 5000 times as of the time this paper is published) and responding to draft versions of this paper. Indicative that the process of podcasting-as-research allows active engagement from both guests and listeners throughout the process of inquiry. In our experience, this greatly enriched the quality of the study compared to regular interviews. Therefore, podcast was considered suitable for studying RHE practises and its main drivers and barriers.

2.2. Research Context and Recruitment

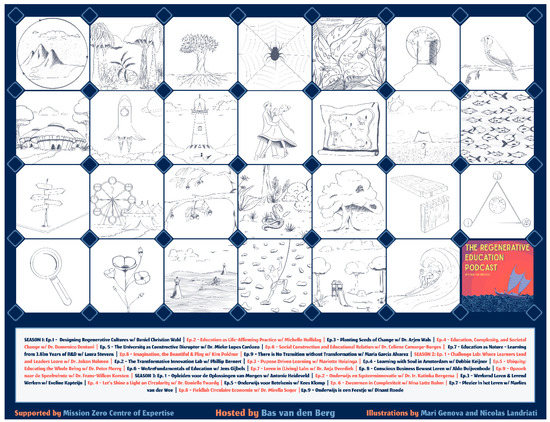

This study used purposive sampling with the following selection criteria: (1) guests had to be practitioners in higher education who in the last three years had been involved with connecting their educational practise with a transition challenge in their region with the intention of facilitating learning-based change towards more (regenerative) sustainable futures. (2) In addition, these activities had to be in the European Union to ensure relative comparability. Finally, no limitations were placed on other personal details such as gender or age, which were used to select participants if the above criteria were met. The first round of invitees were recruited from existing networks of the authors. Each of the guests was also asked to recommend one or two others based on the selection criteria. Finally, an open invite, including the selection criteria, was shared on the LinkedIn profiles of the researchers. This resulted in a total of 52 invitees, of which 31 agreed to participate and a final 27 episodes have been produced and published as The Regenerative Education Podcast on all major streaming platforms. A few of the guests who had originally agreed to participate had to drop out for a variety of reasons. After launch, other potential guests have asked if they could participate in the podcast. These interviews were recorded in April through June 2021 and published in the period from August until October 2021. Because of the unfolding COVID-19 pandemic, considerable flexibility in recording conditions was required. This resulted in a combination of technologies being used for the interviews. The recording and editing have been performed by the first author and the 27-episode podcast features 21 guests active in Dutch universities (of Applied Sciences), 1 in Sweden, 1 in Germany, 1 in France, and 3 who connect with different locations. Of these latter three, two worked for digital-only universities and one worked across several educational institutions. However, in their educational practise, these participants connect strongly with a local place. For this study, we did not limit this connection to places that were necessarily geographically close to the university involved, but rather education that bound itself a particular locality. The episodes ranged from thirty to seventy minutes in total length and included both English (14) and Dutch (12) interviews. A semi-structured interview guide was created that served as the basis for each episode. This guide was shared with each guest a week in advance in line with podcasting best practises. The guide followed roughly a four-part structure, as follows: (1) the journey to now, (2) the educational innovation (3) resistances and drivers and (4) futures. The episode guide can be found in the Appendix A of this paper. The resulting episodes are minimally edited; only specific requests for changes or removal from the guests were performed outside of general audio-quality improvement work like removing background noise, and the time of the episode is representative of the conversation. As all of the authors are native speakers of Dutch, the analysis has been performed in the language of the episodes, and only direct quotes used in the results have been translated into English. The study resulted in a total of 19.4 h of audio materials with an average runtime of 00:44:65 per episode. An overview of the episodes can be seen below in Figure 2. Each of the participants was asked to describe their vision of a preferred future through a metaphor, which served as the basis for Figure 2 below as well as for communicative purposes in the sharing of the podcast.

Figure 2.

Overview of The Regenerative Education Podcast, extended visual overviews can be found in Appendix B, Appendix C and Appendix D.

2.3. Participants

The participants in the course were educators involved with or invited to participate in formal higher education in Europe. They were designers and or teachers with designing responsibilities for the courses that connect with local transition challenges with the intention of acting upon these challenges towards more sustainable futures. They had at least two years of experience in co-designing and teaching such courses. The focus of these interventions was not limited to specific transitions and ranged from circular economy, food through renewable energy. The majority of the participants had PhDs and those who did not were working towards one. Because of the variety of contexts and transitions included the variety of backgrounds of the participants was quite large including art, engineering, and business educators.

2.4. Technology Used

For the recording, SoundTrap, Zoom or the dedicated podcasting studio facilities at The Hague University of Applied Sciences were used depending on the distance and availability of the guest as well as the COVID-19 regulations in The Netherlands during that period. No significant differences were experienced by the host (main author) in the episodes or conversations based on the different recording technologies used or between in-person and distance interviews. For editing, Soundtrap and Audacity were used (e.g., background noise reduction, filler word removal, structuring according to podcast structure and the addition of intro’s/outro’s and music). Buzzsprout serves as podcast host and pushes the episode to Spotify, Google, and Apple podcasts, the three main podcast hosts by popularity. After several months of digital work due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, none of the guests showed difficulty with the use of the technological platforms or unease with sharing their thoughts through these technological media.

2.5. Ethical Challenges

The podcasting-as-inquiry approach represents a particular ethical challenge in anonymization. While there is critique against the ability of interviews to be truly anonymous in the first place (e.g., [63]), anonymization is impossible as the voice of the guest is audible in each podcast episode. It is technically possible to distort voices to be unrecognizable; however, many of the guests indicated they participated partially because of the win-win that the exposure of this method creates, i.e., they participated precisely because it was not anonymous. This also implies that podcasting as a form of qualitative inquiry is most fitting for projects where people want to engage in public debate about that topic. This could lend podcasting primarily to contentious topics. To navigate this ethical challenge, written informed consent for participation, including the publication of names on the platforms was secured. To do so, descriptions of the (ethical) risks of participation were shared in the invitation to participate in the study. In line with recommendations for arts- and creative-based research, a process approach to relational ethics of care guided this inquiry [59]. This included re-asking consent multiple times throughout the research process, including at the start of recordings and after the rough cuts were sent for review, and sharing a draft of this paper for review by the participants. The recordings are saved and processed in accordance with the Wageningen University & Research guidelines on data management, which take all relevant Dutch and EU legislation into account.

2.6. Analysis

The analysis of the final episodes was performed through a transition mapping [31]. This approach draws from transition design [10,64] with an applied narratology [65] focus and utilises abductive analysis to identify relational patterns across the twenty-six collected stories [66]. To find these patterns, each of the episodes is mapped on a transition map, with a time- and system-level axis. This mapping is performed in two rounds of coding, first, the verbatim elements from each story are mapped, before interpretations are added. During these rounds of coding, the research questions and RHE reading guided the process. These coded maps are then clustered and combined into a meta-narrative transition map that combines the insights from each of the separate stories to identify and cluster relational themes. The final step of this analysis includes identifying possible relationships between the clusters and story elements of the participants. These relational themes were then translated through several rounds of internal review across the authors into the set of seven practises and design tools that are presented in the subsequent section. The final step of this analysis included the sharing of the draft version of this paper with the participants of the study for a period of two weeks for review and commentary before submission.

3. Results

Our analysis revealed seven regenerative education design practises that our participants seemed to advocate and enact. Due to the richness and narrative availability of the dataset, as well as pragmatic limitations in word count, the choice was made to present the majority of results in the form of a table, presented here below in Table 1. In this table, you will find the design practises to consider when (re)designing RHE, as well as the drivers and barriers that must be navigated when doing so. By considering these different elements, you as an educator may be able to transform your practise and secure the (institutional) support required to do so. Furthermore, these results have also been transformed into a design tool for practitioners to (re)design their own RHE that connects with STs. Finally, the barriers and drivers identified are presented in Section 3.2 (systemically) and Section 3.3 (personally). Together, Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 engage with the research questions presented in the introduction.

Table 1.

Overview of the Regenerative Education Practises, the main barriers, opportunities, and design questions that could be used to inform (re)design. The ‘you’ in the table refers to educators. The practises can also be considered ‘principles’ to engage with when engaging with RHE.

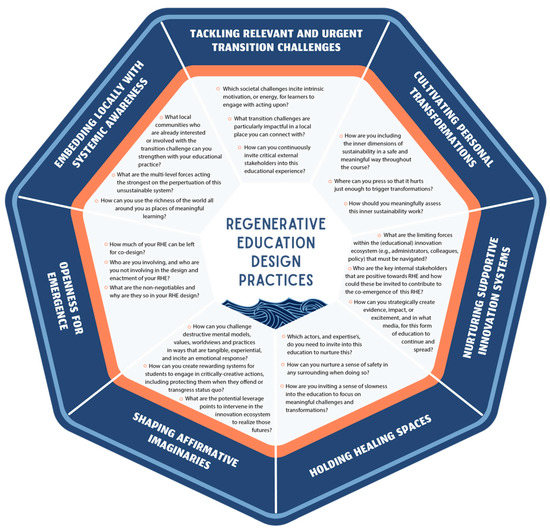

3.1. The Regenerative Education Design Practices Tool (REDPT)

The preliminary REDPT presented below (Figure 3) can be used, together with Table 1, by practitioners to (re)design their own RHE. This preliminary tool emerged through several rounds of iterations on paper conducted by the main author. The practises considered as an educator form the outer ring of the REDPT, while the different design questions that may help you engage with this design practise can be found in the tool. The design tool has been inspired by other examples of design-based templates and tools such as the Business Model Canvas [67], the triple layered business model canvas [68], the Circular Business Model Innovation Tool [69] and the Biomimicry design lens (Biomimicry Institute 3.8) [70]. In subsequent work, the authors will work towards validating and further iterating on the REDPT towards a guide for practitioners, including a full description of how the final tool and guide have been developed and can be used.

Figure 3.

The Regenerative Education Design Practices Tool (REDPT), visualized by Nicolas Landriati.

3.2. (Systemic) Barriers and Drivers

The following are the major systemic barriers and drivers identified. A major barrier that emerged from the study was the importance of supportive ecosystems within the university to provide the space and resources (e.g., time, money, and such) required for RHE. In particular, the need for more time for RHE compared to more traditional education and the tension this creates when trying to move towards an alternative system while ‘trapped’ in the existing one were highlighted strongly by the guests. Few of the guests expressed that they felt supported enough in engaging with this boundary-crossing endeavour. This is in line with the results of recent reviews by Schlaile et al. and Weiss et al. [38,71], which highlight the lack of top-down support to connect universities with real-world challenges. A lack of visible support from the institution was also identified as undermining the success of RHE, as students become disassociated when their surroundings in universities do not (visibly) share an ethos of regenerative sustainability.

The difficulty of navigating university bureaucracy and, in particular, existing practises of education was also identified as a powerful barrier, which aligns with findings in literature by Weiss et al. and Schlaile et al. [38,71]. A strong emphasis here was placed on dealing with assessment and the boards and committees that deal with it. It was highlighted that assessment is difficult because of the openness required for ecological forms of higher education that place transition challenges in context as central to educational design [25,31,72,73]. As it cannot be predicted how those will unfold, setting intended learning outcomes, which are still often the basis for higher education in Western Europe, is contra-productive. A general lack of appropriate ways to judge the different dimensions of learning (such as learning-as-caring, knowing, feeling, anticipating, transforming, transgressing, being) that occur in ecological forms of education was also highlighted [4]. This includes finding ways to assess other than cognitive learning (see [73] for a recent overview of meaningful assessment forms for these other forms of learning).

The importance of choosing and using biophysical spaces, within and outside campus, that are safe for RHE was frequently highlighted, with specific mention made of including natural spaces in the local environment as an active part of the curriculum. The need to actively nurture a sense of safety for the subjective dimensions of learning (spiritual-psychological and socio-emotional), or the personal transformation dimension of working with transitions, was also highlighted, which is in line with scholarship in the psychological literature (e.g., [74,75]). A practical way of creating this safety was found in structural changes to higher education. Namely, creating time for longer and deeper engagement with a particular challenge faced within an RHE context. Examples of these include boot camps, intense short courses, or even entire semesters. This is supposed to be particularly powerful if learners are helped to dive deeper (‘to find the questions behind the question’) during this time and if frequent use of non-campus spaces is included. This is in line with recent discoveries in (living) lab-based education that propose that longer-term engagement but also later in the development of a student, primarily in years three and beyond of undergraduate programmes, is more appropriate for students to engage with ecological forms of education such as RHE [42,76].

3.3. Personal Barriers and Drivers

A large shift in the perspective of the role of ‘teacher’ was highlighted by the guests. Shifting away from an expert who stands in front of the classroom toward a caring gardener, or steward, that nurtures the fertile soils of regeneration (see also [46]). The proposed shift includes moving away from teachers-as-experts to teachers-as-co-designers of entanglements, through which learning-based change can emerge [77]. In the language of transition design, this is a focus on designing alternative systems [10,45]. The (immense) courage, and the relational risk to which you expose yourself, required to transgress, and keep transgressing, the dominant educational paradigm was also highlighted [35]. A professional desire to move towards this alternative role as an educator was identified as the main driver for (personal) change. Towards experimentation with regenerative forms of education.

This transformation in the role of the educator also comes with additional knowledge requirements, such as being able to guide the students through the challenging psychological work that is involved in tackling wicked sustainability problems [72,74,75]. A strong tension was highlighted by the guests between the need for security and growth [75], in the sense that working with STs requires a degree of openness that can be quite uncomfortable for students who are not used to navigating education that embraces such openness (e.g., [42]). Many of the guests highlighted feeling tensions between wanting to intervene to make it simpler for the students to reduce frustration and educationally valuing the difficulty they face in navigating RHE. Several of the guests highlighted a sense of personal fulfilment when they were able to help students navigate these forms of learning and personal transformations, which made their work subjectively more meaningful. A pragmatic way to navigate this tension was used as the inclusion of more diverse educational teams, with at least one member having experience with that more psychological dimension of learning. However, doing this requires a supportive ecosystem inside the university, as well as a financial position as an institution to do so.

In general, the importance of embracing the personal dimensions of RHE, which the guests posited is not invited enough in current educational practise, was highlighted. Additionally, while there is quite an extensive scholarship on ecosocial forms of learning (e.g., [34]), the inclusion of the personal dimensions in sustainability sciences is limited (e.g., [74]). The guests generally agreed with this line of scholarship that such personal sustainability was key for working on transitions. The guests also highlighted that these personal forms of learning are not limited to students but include all learners, including the educators in RHE themselves. Subsequently, the importance of taking a reflexive approach to the unfolding RHE as an educator was mentioned frequently, which is in line with calls for more transformative and ecological approaches to being a scholar-practitioner [8].

4. Discussions

4.1. Towards a RHE

The data suggests a number of key challenges for further movement toward an RHE. In terms of pedagogical-didactical approaches, most of the guests included experiential, contemplative, and/or existential approaches and questions in their practise [37]. Examples of such practises that were mentioned included nature-based learning, walking exercises, and observational assignments related to the challenges that the students are tackling. For this, it is likely that RHE can draw heavily from the field of eco-pedagogy [78]. These practises were considered important, not only because of the embodied and existential nature of wicked sustainability challenges themselves [74], but also as part of the strategy to balance (psychological) safety and growth in designing RHE [75]. However, a full exploration of regenerative pedagogy, or regenerative pedagogies, remains needed.

Most of the gathered stories consist of courses that could be seen as niche innovations at the fringes of education, such as minors or dedicated masters that were designed from the start with a commitment to healing socioecological transgressive systems. This also means that, in most cases, the students flowing into these courses are completely attuned to the more common neoliberal educational paradigm. This was highlighted by the frequent mention of the effort required to break down consumerist expectations of students (e.g., [4]) for a discussion of unsustainability in education. A frequently mentioned example in this regard was the degree to which students are used to working on relatively simple problems that are tightly defined or bounded by their own educational programmes and strong frustrations when asked to co-discover what needed to be worked on and how to go about this as part of a consumerist paradigm of education [79]. This means that a considerable amount of effort and time must be invested by the educators engaging with RHE to break down some of those learned behaviours, such as focusing only on grades instead of personal or transitional impact [4].

The guests shared a commitment to nurturing different dimensions of learning, namely, subjectification, socialization, and qualification [37], with specific mention that those concepts should be rethought through a regenerative sustainability lens. The guests used different vocabularies/concepts to express these dimensions of learning, such as learning-to-care, learning-to-feel, and learning-to-transform [4]. While there were (significant) differences across the cases in how a balance between these was sought, all educators focused strongly on facilitating connection and community-building, within the RHE course as well as with the broader innovation ecosystem within which the RHE is entangled. The focus on tackling regional challenges by connecting with local communities is also a key characteristic derived from ecological university literature as proposed by [34,37], amongst others.

4.2. Using the REDPT

The authors propose that the REDPT could be used by educational teams to (re)design RHE. To do so, these teams should involve a variety of actors from the community, place, and challenge that will be the centre of this educational design. The REDPT could serve as the basis for a workshop or session where collectively the team of educational co-designers goes through the design questions in an iterative manner. The resulting insights and ideas could be used as a starting point for further educational (re)design. Alternatively, the authors propose that the REDPT could be used as an analytical tool to collaboratively reflect on an educational experience and propose improvements, while an in-depth guide and examination of this process is the topic of another study. It is important to highlight the contextual and iterative nature of RHE and that more empirical validation of this tool and its accompanying workshop is required. The authors warmly invite (scholar-)practitioners to experiment and work with the REDPT in (re)designing their own regenerative higher education.

4.3. RHE and Educational Technology

One of the surprising elements of the inquiry was the relatively little emphasis placed on (digital) technologies across the twenty-seven interviews. No strong statements were included about missing, lacking, driving, or in general, the technomediation of ecological forms of learning and learning more generally in the twenty-first century (e.g., [80]). This could indicate that technology does not play a large role in RHE or that it is just not a big priority for these educators. However, given the degree to which education has been technologically mediated, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the likelihood of increased use of technology moving forward, this seems unlikely. Instead, it is possible that more dedicated (digital) technologies are required to be designed to facilitate RHE. This presents a fruitful avenue for further (empirical) research or for perspectives from educational technologists.

4.4. Podcasting-As-Qualitative Inquiry

The results of this research indicate that the entirety of the podcasting process could be used in qualitative inquiry. While this research engaged with a more relational approach (i.e., identifying relational patterns across multiple levels and times), it is likely that podcasting-as-inquiry could be used for more in-depth explorations of a topic, such as a single design disposition, concept, or barrier, or even zooming in on the individual experience of an educator engaging with RHE over time. Of course, this would require methodological adaptations to the study design. As a form of qualitative inquiry, the use of podcasting adds an additional hermeneutical layer that the host (interviewer/researcher) must be conscious of. As you are not only gathering data, but you are also co-creating a communication/educational product for third parties. At times, this was experienced as challenging. Additionally, the authors recommend, whenever feasible, to sit in or be a guest on a podcast before embarking on such an inquiry. The question remains how and if podcasting-as-inquiry would translate to other topics of study. Based on the experience in this study, however, the authors suspect that this will be the case.

4.5. Limitations of the Study

It is possible that the sampling was too homogenous. A large majority of the guests were active, or had been, in Dutch higher education. The experiences of the guests from outside The Netherlands were comparable with those active in The Netherlands, indicating that the identified RHE practises could be represented in other European contexts as well. However, dedicated research in those contexts would be required to state so with confidence. The presented methodology and interview set-up could be used by other scholars who are interested in RHE in other (European) countries, and we warmly invite others to engage with this research. The skewing towards Dutch examples, as well as the highly contextual nature of RHE itself, leads us to consider the results as indicative. It is important to note that in this study, a relational approach to co-constructing knowledge was embraced [61,62], and from that perspective, this situatedness is not a limitation.

A significant limitation consists of the time commitment required for podcast-based inquiry, as each episode takes approximately 10 h of work in additional preparation, recording, editing, and audio improvement as compared to regular interviews. In addition, the cognitive intensity of hosting a conversation while considering third-party listeners was also noted by the main author. Finally, the technical know-how of recording, editing, and producing a podcast can represent a steep learning curve. This could partially be circumvented through the inclusion of specialists for these tasks, but doing so comes with methodological, ethical, and financial implications. It is important to add that, in principle, only the host has to have relatively high levels of technological literacy and the guest only has to be comfortable talking into a microphone. However, as we argued previously, because of the benefits that podcasting-as-inquiry presents for research and outreach, we strongly believe the methodology has merit despite the potential limitations.

5. Conclusions

The emergence of RHE represents a frontier for sustainability- and educational scholars alike who are interested in the intersection of (higher) education, regenerative sustainability, and systemic change. While this study limited itself to higher education, of particular interest are studies exploring other forms of (institutionalized) RHE. Our results indicate that (further) validation of the REDPT, as well as exploration of alternative design practises and tools, are also warranted. The guests that participated in this study showcase the potential for a more RHE by showing that such redesign and redoing is, in fact, possible. Interestingly, none of the guests highlighted the importance of competencies, sustainability-oriented or otherwise, which presents an interesting and fruitful avenue for inquiry. In addition, further explorations of how educators start to engage with RHE, i.e., the impetus for personal transformation within the educators to transform how they work, present an avenue of research of particular importance. Through this study, we propose seven key design practises for embracing RHE as a possible future for universities to play a role in the bumpy decades to come. The study also highlights a number of personal and systemic barriers that call for personal and systemic change within higher education. While the nuances of how to engage with these different elements are context-dependent and are precisely where the artistry of education resides [37]. The REDPT does provide a guide to engage with such (re)design and (re)doing. We hope so and invite you to experiment with the REDPT and RHE in service of a more sustainable future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.v.d.B., K.P., E.S. and A.W.; Formal analysis, B.v.d.B., K.P., E.S. and A.W.; Investigation, B.v.d.B.; Methodology, B.v.d.B., K.P., E.S. and A.W.; Supervision, K.P., E.S. and A.W.; Visualization, B.v.d.B.; Writing—original draft, B.v.d.B.; Writing—review & editing, K.P., E.S. and A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding the APCs were covered by the Research Centre Mission Zero of The Hague University of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No ethical approval of the sorts was sought as the research design was approved by a committee at The Wageningen University & Research as part of a larger PhD proposal as well as the Dutch Science Organization in a similar process. This conclusion was reached because there was no risk identified with participating in the research. All participants were informed extensively (see attached empty form) and asked multiple times if they were still okay with participating (even after signing). Also, none of the participants are identifiable in the manuscript (the script only includes 7 direct anonymous quotes are used in the manuscript out of a total of 27 episodes).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

All data for this study are available in full on all major podcast streaming platforms including Spotify, Google Podcasts and Apple Podcasts. The link can be found in the text.

Acknowledgments

This work would not have been possible without the support of Centre of Expertise Mission Zero, the availability of equipment and time to learn how to make a podcast was invaluable. Of course, this work owes a debt of gratitude to each of the amazing guests that have contributed their educational stories to the podcast and this work. The authors would also like to highlight the contributions of Mari Genova and Nicolas Landriati for their assistance in visualization of digital artworks and the metaphors of the guests. In addition, we would like to thank Jamie B. Smith for kindly taking the time to review and comment on earlier drafts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Consent and Information Form

Dear [GUEST_NAME_HERE],

I’m excited to get the chance to chat with you soon for our scheduled podcast episode on [DATE_HERE].

Here are just a few tips and suggestions to ensure we both get the most out of this time together:

- If you have one, please be prepared to use a podcasting microphone for this interview.

- If you can’t do this, please use a set of earbuds like the ones that come with your smartphone. They provide higher quality sound than your computer’s native microphone.

- Please be in a quiet room for our call where you’re not likely to be interrupted. Ideally this is NOT a conference room or other large space with a lot of hard, flat surfaces. These create more echo and reverb than a smaller space with things like a couch or other soft surfaces.

- Please turn off your cell phone and notifications on your computer for our call.

- Our call with last approximately 90 min with time for a bit of prep ahead of the interview and to wrap things up at the end.

- Please note that the software only works in the CHROME browser.

Here are the topics that I’d like to cover during our interview (also see the structure of the final episode below for an indication of the questions). We’ll likely digress a bit, but this is a general feel for where I’d like to take things:

- ○

- The story of your education that connects to sustainability, regeneration and/or place.

- ○

- What this experience was like for learners and the impact it had on you and your students.

- ○

- The barriers and opportunities you experienced during this story.

- ○

- Your vision of higher education in 5–10 years based on this story.

- ○

- A metaphor that represents the purpose of your education.

I suggest you prepare your thoughts and answers based on the above topic in advance, as it will improve the quality of the recording.

I will follow up after our episode and ahead of when this episode will go live to provide you with a link to share our episode and some social media assets that you can use to best help promote your episode. If you have any questions or need anything ahead of our interview, please let me know here via email. Thanks so much and looking forward to talking on [DATE_HERE].

Warm regards,

Bas van den Berg

Please note that this gives a generalized overview of the structure of an episode of The (Re)generative Education Podcast.

Metaphor Tease (2 min or less):

Each episode will open with a metaphor that you will use in the podcast episode to describe your higher educational practise.

------------------------------------MUSIC INTRO (15 s or less) -------------------------------------

Introduction: Hi and welcome to The (Re)generative Education Podcast with Bas van den Berg, where we talk to leading higher educators that connect their education with sustainability transformations. In each episode, we will explore a story of inspiring and purpose-driven teachers who are challenging our conceptions of education in times of profound societal and systemic change. Thank you for listening and enjoy the podcast.

------------------------------------THEME SONG (10 s or less) -------------------------------------

Expert/Topic Introduction (10–15 s): In this part I will introduce you as a guest, If, there are specific parts, books, articles, videos and such you’d like to be mentioned here please let me know. I will base this on materials supplied by you and/or what can be found online based on your digital presence.

Interview, Part 1 (5–10 min).

- How would you describe your education that connects Higher education to place and sustainability/regeneration?

- What is a week in this education like?

- How did you become involved with this education?

- How did this education become reality?

------------------------------------THEME SONG (10 s or less) -------------------------------------

Interview, Part 2 (5–10 min)

- What is it like to be a learner in this education?

- How has this education impacted you and the other learners?

- How would you describe this as metaphor?

------------------------------------THEME SONG (10 s or less) -------------------------------------

Interview, Part 3 (5–10 min)

- What are the most important mechanisms and qualities that make this type of education work?

- What were the (systemic) challenges you face(d) and opportunities you explore to do this?

------------------------------------THEME SONG (10 s or less) -------------------------------------

Interview, Part 4 (5–10 min)

- How would you describe your educational dream in 5–10 years?

- What is needed to make this hope new educational reality?

Thank you to the guest for your time and energy today.

Show Goodbye (15–30 s)

That wraps up our show for today. Thanks for listening to The Regenerative Education Podcast with your host Bas. If you enjoyed this episode, please share and subscribe. Till the next story!

------------------------------------MUSIC OUTRO (15 s or less) -------------------------------------

Appendix B. Visual Summary of Season 1 of The Regenerative Education Podcast

Appendix C. Visual Summary of Season 2 of The Regenerative Education Podcast

Appendix D. Visual Summary of Season 3 of The Regenerative Education Podcast

References

- Kopnina, H. Education for the future? Critical evaluation for education for sustainable development goals. J. Environ. Educ. 2020, 50, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servant-Miklos, V. The Love at the End of the World. Towards an Existential Ecological Ethic. Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/jbpa-2020-0009/html?lang=en (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V.P., Zhai, A., Pirani, S.L., Connors, C., Péan, S., Berger, N., Caud, Y., Chen, L., Goldfarb, M.I., Gomis, M., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.J. Transgressing the hidden curriculum of unsustainability: Towards a relational pedagogy of hope. Educ. Philos. Theory 2019, 52, 825–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist; Random House UK: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 97818479-41398. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, D.C. Designing Regenerative Cultures; Triarchy Press: Bridport, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781909470774. [Google Scholar]

- Tafuni, V.; Heß, J. Education for Sustainable Development as a Catalyst and the Role of Students in the Future Management of HEIs. In Proceedings of the Keynote at the Bologna Process Conference, Bologna, Italy, 24 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmayer, J.M. Transformative Research: Knowledge and Action for Just Sustainability Transitions. DIT Working Paper for Positioning Transformative Research. Rotterdam, Design Impact Transition Platform; Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. Processes and patterns in transitions and system innovations: Refining the co-evolutionary multi-level perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2005, 72, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, T. The Emerging Transition Design Approach. In Proceedings of the Design Research Society 2018 Catalyst Conference, Limerick, Ireland, 25–28 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, B. Shifting from ‘sustainability’ to regeneration. Build. Res. Inf. 2007, 35, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyle, J.T. Regenerative Design for Sustainable Development; Wiley international Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-471-17843-9. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, H.S.; DeVille, N.V.; Stoddard, O.; Cole, J.; Myers, S.S.; Li, H.; Elliott, E.G.; Jimenez, M.P.; James, P.; Golden, C.D. Sustaining Planetary Health through Systems Thinking: Public Health’s Critical Role. SSM -Popul. Health 2021, 15, 100844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mang, P.; Haggard, B. Regenerative Development and Design—A Framework for Evolving Sustainability; Regenesis Institute: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-118-97286-1. [Google Scholar]

- Klomp, K.; Oosterwaal, S. Thrive: Fundamentals for a New Economy; Business Contact: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; ISBN 9789047014751. [Google Scholar]

- Poldner, K.A. Entrepreneuring a Regenerative Society; Inaugural Address: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Xiong, R.; Li, H.; Sun, Q.; Yang, J. Pathways for Sustainable Energy Transition. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1564–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertola, P. Fashion Within the Big Data Society: How can data enable fashion transition towards a more meaningful and sustainable paradigm? In Proceedings of the Conference Paper: CHItaly ‘21: 14th Biannual Conference of the Italian SIGCHI Chapter, Bolzano, Italy, 11–13 July 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Jain, S.; Malhotra, G. The Anatomy of Circular Economy Transition in the Fashion Industry. Soc. Responsib. 2020, 17, 524–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigboldus, S. On Food System Transitions & Transformations: Comprehensive Mapping of the Landscape of Current Thinking, Research, and Action; Wageningen Centre for Development Innovation: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereno, A.; Eriksson, D. A multi-stakeholder perspective on sustainable healthcare: From 2030 onwards. Futures 2020, 122, 102605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers, P.; van Mierlo, B.; Hoes, A.-C. Toward an integrative perspective on social learning in system innovation initiatives. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wals, A.E.J. Sustainability-Oriented Ecologies of Learning: A Response to Systemic Dysfunction; Chapter in Ecologies of Learning and Practice by Barnett & Jackson; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; ISBN 9781351020268. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, K.; Tilbury, D. Whole-School Approaches to Sustainability: An International Review of Sustainable School Programs; Report Prepared by the Australian Research Institute in Education for Sustainability (ARIES) for the Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australian Government; Australian Research Institute in Education for Sustainability (ARIES): Macquarie Park, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, B.; den Hoedt, T.; van den Eijk, E. Learning for circularity—Designing higher for education for circular economy. In Circular Economy: Challenges and Opportunities for Ethical and Sustainable Business; Poldner, K., Kopnina, H., Eds.; Routledge Book: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Armon, C. Regenerative Collaboration in Higher Education: A Framework for Surpassing Sustainability and Attaining Regeneration. Philosophies 2021, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonetti, G.; Brown, M.; Naboni, E. About the Triggering of UN Sustainable Development Goals and Regenerative Sustainability in Higher Education. Sustainability 2019, 11, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lopes Cardozo, M.T.A. Learning to Become Smart Radicals: A Regenerative Lens on the Potential for Peace and Reconciliation through Youth and Education Systems. J. Educ. Emergencies 2022, 8, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, B. Regenerative Higher Education—Connecting University Education with Societal Transition Challenges. DIES Natalis Symposium 2022, 9th of March, Wageningen University & Research, Wageningen, The Netherlands. 2022. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3xzKSJuaXsw (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Maedows, D. Leverage Points Places to Intervene in a System; Sustainability Institute: Hartland, WI, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, B. Regenerative Education for The Ecological University in Times of Socio-Ecological Crises—Educational Design Dispositions, Qualities, Opportunities & Barriers. In Proceedings of the 2nd Barcelona Conference on Education, Barcelona, Spain, 8 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, B.; Poldner, K.A.; Sjoer, E.; Wals, A.E.J. Regenerative Education for the Ecological University. In Entangled (im)materialities: Transdisciplinary Posthuman Interventions; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, in review.

- Barnett, R. The Ecological University—A Feasible Utopia; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781138720763. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, R.; Jackson, N. Ecologies for Learning and Practice: Emerging Ideas, Sightings, and Possibilities, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-113-8496-880. [Google Scholar]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Wals, A.E.; Kronlid, D.; McGarry, D. Transformative, transgressive social learning: Rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 16, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Berlin Declaration on Education for Sustainable Development. 2021. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/esdfor2030-berlin-declaration-en.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Biesta, G. World-Centred Education: A View for the Present; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; ISBN 978–03675-65527. [Google Scholar]

- Schlaile, M.P.; Kask, J.; Brewer, J.; Bogner, K.; Urmetzer, S.; De Witt, A. Proposing a Cultural Evolutionary Perspective for Dedicated Innovation Systems: Bioeconomy Transitions and Beyond. J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 2022. Available online: https://www.cairn.info/revue-journal-of-innovation-economics-2022-2-page-93.htm (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Verhoef, L.A.; Bossert, M.; Newman, J.; Ferraz, F.; Robinson, Z.P.; Agarwala, Y.; Wolff, P.J.; Jiranek, P.; Hellinga, C. Towards a Learning System for University Campuses as Living Labs for Sustainability; Universities as Living Labs for Sustainable Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Braidotti, R. Posthuman Knowledge, 1st ed.; Polity Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; ISBN 978–1509535262. [Google Scholar]

- Overdiek, A.; Geerts, H. Innoveren Met Labs: Hoe Doe Je Dat? Ervaringen Met Future-Proof Retail; Future-Proof Retail Boek: Paperback, The Nederlands, 2021; ISBN 9789083078007. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Heuvel, R.; Braun, S.; de Bruin, M.; Daniëls, R. A Closer Look at Living Labs and Higher Education Using a Scoping Review. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2021, 11, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg, J.; Larsson, J. Challenge lab—Learning by engaging in society’s sustainability transitions. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Researching Work and Learning, Grahamstown, South Africa, 6–8 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg, J.; Larsson, J. A Sustainability Lighthouse—Supporting Transition Leadership and Conversations on Desirable Futures. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia, G.G.; Gaziulusoy, I. Designing future experiences of the everyday: Pointers for methodical expansion of sustainability transitions research. Futures 2021, 127, 102702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, T. The Transgressive Gardener; Cultivating Learning-Based Transformations for Regenerative Futuers. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University & Research, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2019. Available online: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/557436 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Orr, D.W. The Nature of Design—Ecology, Culture, and Human Intention; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pisters, S.; Vihinen, H.; Figueiredo, S. Inner change and sustainability initiatives: Exploring the narratives from ecovillagers through a place-based transformative learning approach. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deloitte. The Ears Have It. 2020. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/cn/en/pages/technology-media-and-telecommunications/articles/tmt-predictions-2020-rise-of-audiobooks-podcast-industry.html (accessed on 25 December 2021).

- Cook, I.M. Critique of Podcasting as An Anthropological Method. Ethnography 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundstrom, M.; Lundstrom, T.L. Podcast Ethnography. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2020, 24, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcham, P.; Zhang, X. Podcasting in academia: A new knowledge management paradigm within academic settings. In Proceedings of the 2006 ACM SIGMIS CPR Conference on Computer Personnel Research: Forty Four Years of Computer Personnel Research: Achievements, Challenges & the Future, Claremont, CA, USA, 13–15 April 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, J.B. Podcasting as Social Scholarship: A Tool to Increase the Public Impact of Scholarship and Research. J. Soc. Soc. Work. Res. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, L.; Cunsolo, A.; Castleden, H.; Martin, D.; Hart, C.; Anaviapik-Soucie, T.; Russell, G.; Paul, C.; Dewey, C.; Harper, S.L. The expanding digital media landscape of qualitative and decolonizing research: Examining collaborative podcasting as a research method. MediaTropes 2017, 7, 203–228. [Google Scholar]

- Kinkaid, E.; Brain, K.; Senanayake, N. The podcast-as-method? Critical reflections on using podcasts to produce geographic knowledge. Geogr. Rev. 2019, 110, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celaya, I.; Ramírez-Montoya, M.S.; Naval, C.; Arbués, E. Uses of the podcast for educational purposes. Systematic mapping of the literature in WoS and Scopus (2014–2019). RLCS Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2020, 77, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, C. Education Podcasts: A Genre Analysis. E-Learn. Digit. Media 2017, 14, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronek, P.; Boddy, J.; Chenoweth, L.; Clark, J. A Report on the Use of Open Access Podcasting in the Promotion of Social Work. Pract. Policy Perspect. 2016, 69, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, H. Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide, 2nd ed.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1447316275. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. Interview Views: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Z.; Bohmne, J.; Wamsler, C. Towards a Relational Paradigm in Sustainability research, practice, and education. Ambio 2021, 50, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- West, S.; Haider, L.J.; Stålhammar, S.; Woroniecki, S. A relational turn for sustainability science? Relational thinking, leverage points and transformations. Ecosyst. People 2020, 1, 304–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Kitzinger, J.; Kitzinger, C. Anonymising interview data: Challenges and compromise in practice. Qual. Res. 2015, 15, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Irwin, T. Transition Design: A Proposal for a New Area of Design Practice, Study, and Research. Des. Cult. 2015, 7, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moenander, S.J. When Not to Tell Stories: Unnatural Narrative in Applied Narratology. Front. Narrat. Stud. 2018, 4, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavory, L.; Timmermans, S. Theory construction in qualitative research from grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociol. Theory 2012, 30, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation—A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers and Challengers; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, A.; Paquin, R.L. The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1473–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, B.; Poldner, K.A.; den Hoedt, T. Learning Towards a Circular Economy: A New Research Direction for Circular Business? In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on New Business Models, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 1–2 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Biomimicry Institute. The Biomimicry 3.8 Design Lens. Available online: https://biomimicry.net/the-buzz/resources/biomimicry-designlens/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Weiss, M.; Barth, M.; Wiek, A.; von Wehrden, H. Drivers and Barriers of Implementing Sustainability Curricula in Higher Education—Assumptions and Evidence. High. Educ. Stud. 2021, 11, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenten, J.; Bohm, N.L.; Van den Berg, B. Learners Engaging with Complexity and Uncertainty in Sustainability Transitions in Higher Education. In Proceedings of the 2nd Barcelona Conference on Education, Barcelona, Spain, 8–11 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Boor, I.; Gerritsen, D.; De Greef, L.; Rodermans, J. Meaningful Assessment for Interdisciplinary Education: A Practical Handbook for University Teachers; University of Amsterdam Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ives, C.D.; Freerth, R.; Fischer, J. Inside-out Sustainability: The Neglect of Inner Worlds. Ambio 2020, 49, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaufman, S.B. Transcend: The New Science of Self-Actualization; TarcherPerigee: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0143131205. [Google Scholar]

- Sjoer, E.; Hensel, R.W. Enthousiasme als Motor. In Innoveren Met Labs: Hoe Doe Je Dat? Ervaringen Met Future-Proof Retail; Future-Proof Retail Boek: Paperback, The Nederlands, 2021; ISBN 9789083078007. [Google Scholar]

- Sanford, C. The Regenerative Life: Transform Any Organization, Our Society, and Your Destiny; Nicholas Brealey: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1529308211. [Google Scholar]

- Misiaszek, G.W. Ecopedagogy Critical Environmental Teaching for Planetary Justice and Global Sustainable Development; Bloomsbury Publishing Ltd.: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 9781350083790. [Google Scholar]

- Winstone, N.E.; Boud, D. The need to disentangle assessment and feedback in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2021, 47, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Z. If Education Is Not the Answer You Are Asking the Wrong Question. Perspectiva. 2019. Available online: zakstein.org (accessed on 8 June 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).