The Moderating Role of Age in the Effect of Video Playback Speed on Urgency Perception in the Context of Climate Change

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“There is one issue that will define the contours of this century more dramatically than any other, and that is the urgent threat of a changing climate.”—Barack Obama

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Video at a Fast Playback Speed

2.2. Video Playback Speed and Climate Change Urgency Perception

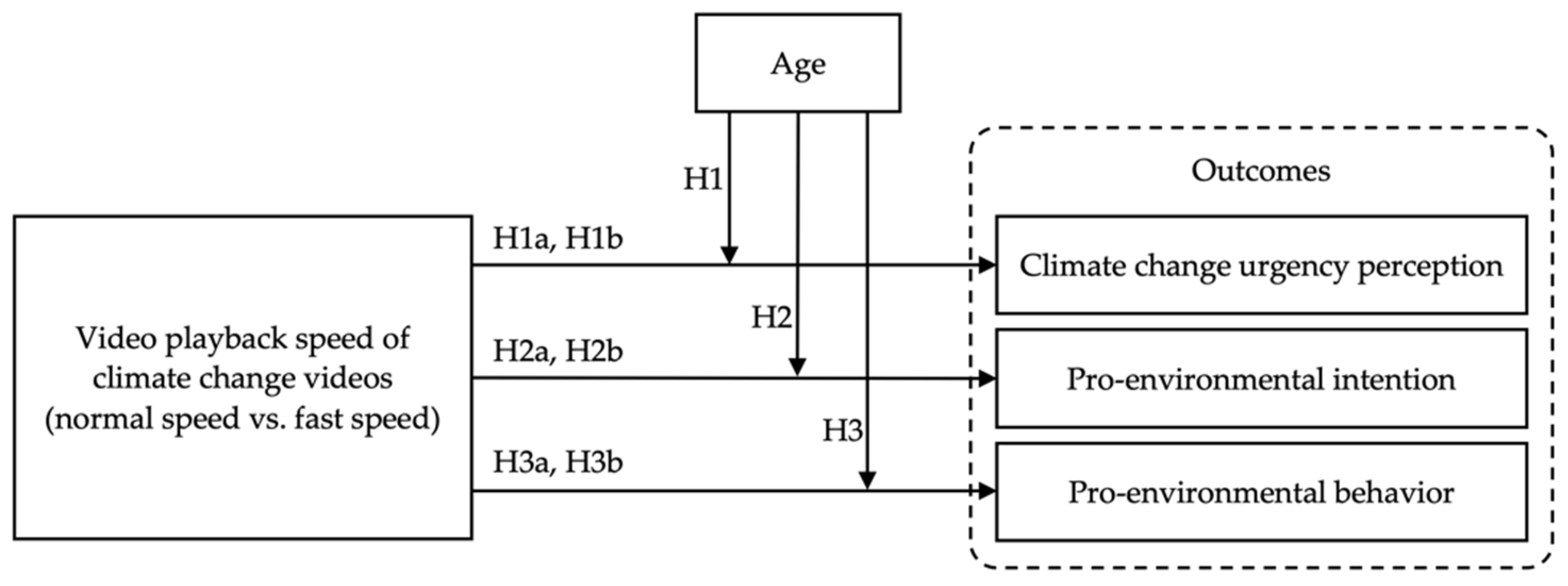

2.3. The Moderating Role of Age in the Effect of Video Playback Speed on Climate Change Urgency Perception

2.4. Downstream Effects on ProEnvironmental Intention and Behavior

3. Pilot Study

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Procedure, Participants, and Design

3.1.2. Measures

3.1.3. Data Analysis

3.2. Results

4. Main Study

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Procedure, Participants, and Design

4.1.2. Measures

4.1.3. Data Analysis

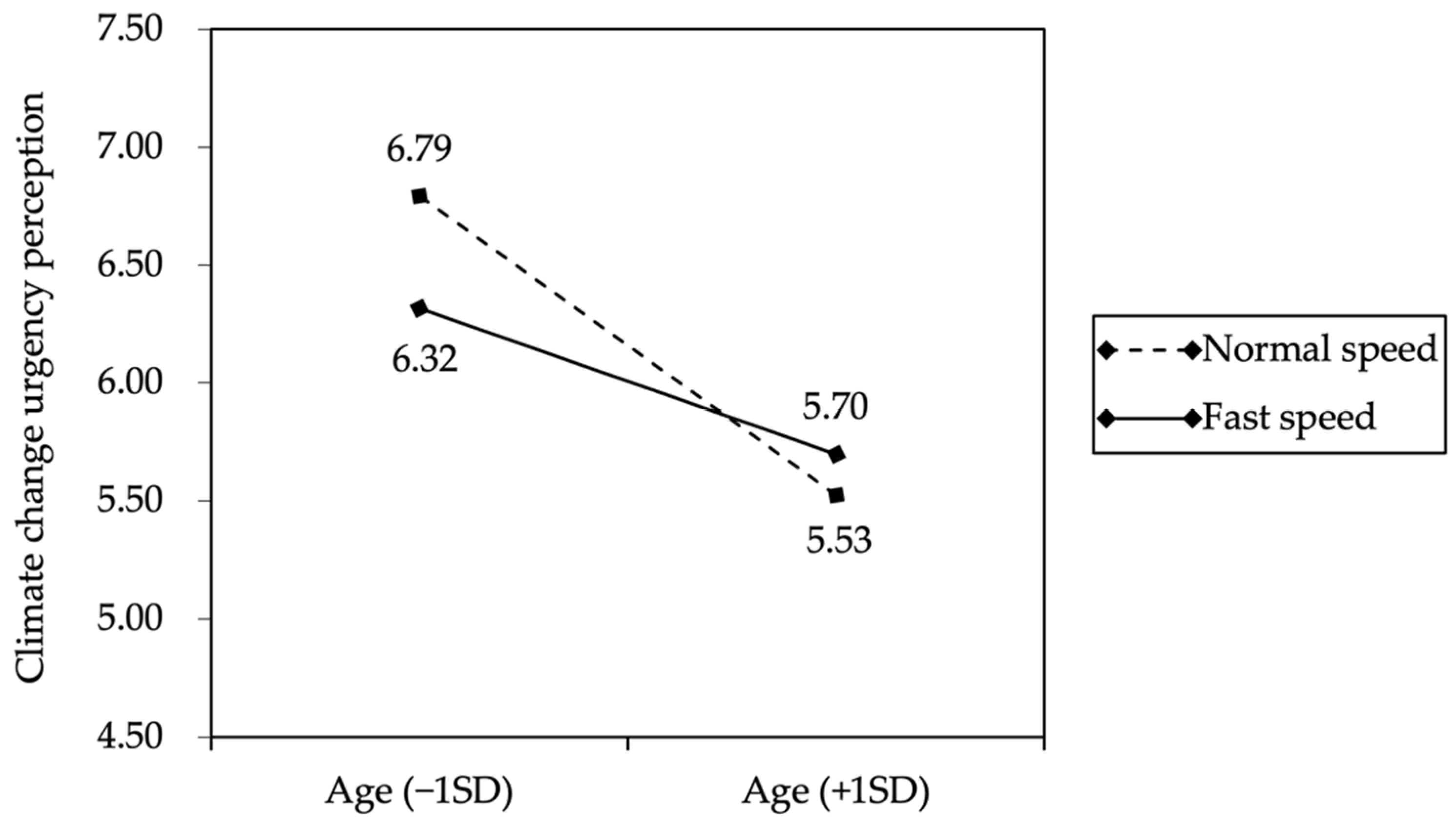

4.2. Results

5. General Discussion

5.1. Results Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2022. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/ (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Assembly, U.G. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. Climate Change: What Is a Climate Emergency? BBC News. 2019. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-47570654 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Wilson, A.J.; Orlove, B. What Do We Mean When We Say Climate Change Is Urgent? Center for Research on Environmental Decisions Working Paper 1; Earth Institute, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Wang, W.; Jiang, S.; Huang, Q.; Gao, W. Detecting violent scenes in movies by auditory and visual cues. In Proceedings of the 9th Pacific-Rim Conference on Multimedia, Tainan, China, 9–13 December 2008; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.A.; Suk, H.J. Affective effect of video playback style and its assessment tool development. Sci. Emot. 2016, 19, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, W. Apple’s ‘Don’t Blink’ Video Is the Most Thrilling Commercial You Will See This Year. Blasting News US. 2016. Available online: https://us.blastingnews.com/opinion/2016/09/apple-s-don-t-blink-video-is-the-most-thrilling-commercial-you-will-see-this-year-001106773.html (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Driedger, J.; Müller, M. A review of time-scale modification of music signals. Appl. Sci. 2016, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasel, S.A.; Gips, J. Breaking through fast-forwarding: Brand information and visual attention. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- LaBarbera, P.; MacLachlan, J. Time-compressed speech in radio advertising. J. Mark. 1979, 43, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorains, M.; Ball, K.; MacMahon, C. Expertise differences in a video decision-making task: Speed influences on performance. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzhaupt, A.D.; Barron, A. Effects of time-compressed narration and representational adjunct images on cued-recall, content recognition, and learner satisfaction. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2008, 39, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.; Chen, G.; Mirzaei, K.; Paepcke, A. Is faster better? A study of video playback speed. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (LAK’20), Frankfurt, Germany, 23–27 March 2020; pp. 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ness, I.; Opdal, K.; Sandnes, F.E. On the convenience of speeding up lecture recordings: Increased playback speed reduces learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Technologies and Learning (ICITL), 29 November–1 December 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzhaupt, A.D.; Pastore, R.; Davis, R. Effects of captions and time-compressed video on learner performance and satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Chakraborty, A.; Dawson, M.; Dugan, A.; Adkins, B.; Doty, C. Does the podcast video playback speed affect comprehension for novel curriculum delivery? A randomized trial. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 19, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelly, J.D.; Petersen, A.; Lendvay, T.S.; Kowalewski, T.M. The effect of video playback speed on perception of technical skill in robotic surgery. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2020, 15, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jia, H.; Kim, B.K.; Ge, L. Speed up, Size down: How animated movement speed in product videos influences size assessment and product evaluation. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Jia, J.S.; Zheng, W. The effect of slow motion video on consumer inference. J. Mark. Res. 2021, 58, 1007–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Bang, H.; Choi, D.; Kim, K. Slow versus fast: How speed-induced construal affects perceptions of advertising messages. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 40, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, K.C.; Finkel, E.J.; Allan, D.; Fitzsimons, G.M. On the dangers of pulling a fast one: Advertisement disclaimer speed, brand trust, and purchase intention. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 38, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fink, B.; Wübker, M.; Ostner, J.; Butovskaya, M.L.; Mezentseva, A.; Muñoz-Reyes, J.A.; Sela, Y.; Shackelford, T.K. Cross-cultural investigation of male gait perception in relation to physical strength and speed. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malik, S.; Sayin, E. Hand movement speed in advertising elicits gender stereotypes and consumer responses. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 39, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivel, J.; Bernasconi, F.; Manuel, A.L.; Murray, M.M.; Spierer, L. Dynamic calibration of our sense of time. Neuropsychologia 2011, 49, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyman, T.J.; Karlsson, E.P.A.; Antfolk, J. As time passes by: Observed motion-speed and psychological time during video playback. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, A.J.; Orlove, B. Climate urgency: Evidence of its effects on decision making in the laboratory and the field. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 51, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügger, A.; Dessai, S.; Devine-Wright, P.; Morton, T.A.; Pidgeon, N.F. Psychological responses to the proximity of climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fesenfeld, L.P.; Rinscheid, A. Emphasizing urgency of climate change is insufficient to increase policy support. One Earth 2021, 4, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, A.; Marsh, J.E.; Richardson, B.H.; Ball, L.J. A systematic review of the psychological distance of climate change: Towards the development of an evidence-based construct. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiella, R.; La Malva, P.; Marchetti, D.; Pomarico, E.; Di Crosta, A.; Palumbo, R.; Cetara, L.; Di Domenico, A.; Verrocchio, M.C. The psychological distance and climate change: A systematic review on the mitigation and adaptation behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 568899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, P.S. Designing acoustic and non-acoustic parameters of synthesized speech warnings to control perceived urgency. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2007, 37, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edworthy, J.; Loxley, S.; Dennis, I. Improving auditory warning design: Relationship between warning sound parameters and perceived urgency. Hum. Factors 1991, 33, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellier, E.J.; Edworthy, J.; Dennis, I.A.N. Improving auditory warning design: Quantifying and predicting the effects of different warning parameters on perceived urgency. Hum. Factors 1993, 35, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, G.C. Music, mood, and marketing. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Communication and Persuasion; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.M.; Shaffer, D.R. Speed of speech and persuasion: Evidence for multiple effects. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 21, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.A.; Le Nguyen, V.T.U.; Wi, J.Y. Remote control marketing: How ad fast-forwarding and ad repetition affect consumers. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2002, 20, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.W.; Cutright, K.M.; Chartrand, T.L.; Fitzsimons, G.J. Distinctively different: Exposure to multiple brands in low-elaboration settings. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 40, 973–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Petty, R.E.; Feinstein, J.A.; Jarvis, W.B.G. Dispositional differences in cognitive motivation: The life and times of individuals varying in need for cognition. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 119, 197–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, E. Depth and elaboration of processing in relation to age. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Learn. Mem. 1979, 5, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spotts, H. Evidence of a relationship between need for cognition and chronological age: Implications for persuasion in consumer research. In Advances in Consumer Research, Association for Consumer Research; Allen, C.T., John, D.R., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1994; Volume 21, pp. 238–243. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.D. Age differences in encoding, storage, and retrieval. In New Directions in Memory and Aging; Poon, L.W., Fozard, J.L., Cermak, L.S., Arenberg, D., Thompson, L.W., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1980; pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Petty, R.E. The need for cognition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 42, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugtvedt, C.P.; Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Need for cognition and advertising: Understanding the role of personality variables in consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 1992, 1, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Stayman, D.M. The role of mood in advertising effectiveness. J. Consum. Res. 1990, 17, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlove, B.; Shwom, R.; Markowitz, E.; Cheong, S.M. Climate decision-making. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2020, 45, 271–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, Y.; Gifford, R. Free-market ideology and environmental degradation: The case of belief in global climate change. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 48–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, M.; Blamkenberg, A.-K. Environmental concern, volunteering and subjective well-being: Antecedents and outcomes of environmental activism in Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 124, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, G.L.; Babutsidze, Z.; Chai, A.; Reser, J.P. The role of climate change risk perception, response efficacy, and psychological adaptation in pro-environmental behavior: A two nation study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F. Impact of fear appeals on pro-environmental behavior and crucial determinants. Int. J. Advert. 2016, 35, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panno, A.; Carrus, G.; Maricchiolo, F.; Mannetti, L. Cognitive reappraisal and pro-environmental behavior: The role of global climate change perception. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 45, 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickard, L.N.; Yang, Z.J.; Schuldt, J.P. Here and now, there and then: How “departure dates” influence climate change engagement. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 38, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, D.M.; Meyvis, T.; Davidenko, N. Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Wei, F.; Cao, H.; Yao, Y. Impact of power on green consumption. J. Tianjin Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 4, 76–80. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloot, D.; Jans, L.; Steg, L. Is an appeal enough? The limited impact of financial, environmental, and communal appeals in promoting involvement in community environmental initiatives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, X. Income and geographically constrained generosity. J. Consum. Aff. 2022, 56, 766–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, E.; Brandimarte, L.; Samat, S.; Acquisti, A. Beyond the Turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 70, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahardika, H.; Thomas, D.; Ewing, M.T.; Japutra, A. Comparing the temporal stability of behavioural expectation and behavioural intention in the prediction of consumers pro-environmental behaviour. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, B.S.; Chrysochou, P.; Christensen, J.D.; Orquin, J.L.; Barraza, J.; Zak, P.J.; Mitkidis, P. Stories vs. facts: Triggering emotion and action-taking on climate change. Clim. Chang. 2019, 154, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shani-Feinstein, Y.; Kyung, E.J.; Goldenberg, J. Moving, fast or slow: How perceived speed influences mental representation and decision making. J. Consum. Res. 2022, forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermiller, C. The baby is sick/the baby is well: A test of environmental communication appeals. J. Advert. 1995, 24, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K.; Allen, M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ. Behav. 2000, 27, 591–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendt, F.; Matthes, J. Nature documentaries, connectedness to nature, and pro-environmental behavior. Environ. Commun. 2016, 10, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, H.B.; Nugent, M.R. Straw wars: Pro-environmental spillover following a guilt appeal. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dixon, G.; Hmielowski, J.D. Psychological reactance from reading basic facts on climate change: The role of prior views and political identification. Environ. Commun. 2019, 13, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.L.; Eisert, J.L.; Garcia, A.; Lewis, B.; Pratt, S.M.; Gonzalez, C. Multimodal urgency coding: Auditory, visual, and tactile parameters and their impact on perceived urgency. Work 2012, 41, 3586–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Study | Context/Stimuli | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Grivel et al. [24] | Natural scenes of a crowded street | People’s sense of time was dependent on the speed of their visual environment. |

| Herbst et al. [21] | End-of-advertisement disclaimers | Fast (vs. normal-paced) end-of-advertisement disclaimers were perceived as less credible, which incurred less purchase intention. |

| Nyman et al. [25] | Natural scenes of an indoor market space | Video playback speed did not predict peoples’ time estimates. |

| Fink et al. [22] | Walking speed perception | Strength perceptions and attractiveness ratings of walkers did not differ between the fast speed and the normal-speed condition. |

| Jia et al. [18] | Product advertising (e.g., audio speaker) | Consumers estimated the size of an immobile product to be smaller when it was animated to move faster in videos. |

| Yoon et al. [20] (Study 3 and 4) | Product advertising (Nikon cameras) | When TV commercials played slowly (rapidly), consumers preferred high-construal (low-construal) advertising appeals that emphasized quality (price). |

| Malik and Sayin [23] (Study 1B) | Hand movement speed perception | People implicitly associated speedy movements with a more masculine (than feminine) behavior. |

| Yin et al. [19] (Study 6) | Product advertising (Nature’s Essence face wash) | Playing a commercial at fast speed (vs. natural speed) led to a marginally more negative product evaluation and greater visual difficulty. The effect of fast speed might be explained by lower perceived amounts of information that were induced by greater difficulty in visual processing. |

| Present research | Climate change urgency | Fast playback speed led to lower perceived urgency of climate change for younger consumers compared to normal playback speed. |

| Variables | Speed | Intention | Behavior | Urgency | Age | Gender | Income | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speed | 1 | – | – | ||||||

| Intention | −0.088 | 1 | 4.51 | 1.54 | |||||

| Behavior | 0.050 | 0.273 ** | 1 | 0.24 | 0.43 | ||||

| Urgency | −0.023 | 0.430 ** | 0.119 * | 1 | 6.07 | 1.45 | |||

| Age | −0.092 | −0.037 | −0.023 | −0.328 ** | 1 | 37.83 | 13.78 | ||

| Gender | 0.020 | 0.162 ** | 0.054 | 0.178 ** | −0.245 | 1 | 1.50 | 0.50 | |

| Income | 0.019 | 0.114 * | 0.072 | 0.037 | 0.024 | −0.124 * | 1 | 6.94 | 3.57 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sheng, X.; Mo, T.; Zhou, X. The Moderating Role of Age in the Effect of Video Playback Speed on Urgency Perception in the Context of Climate Change. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148923

Sheng X, Mo T, Zhou X. The Moderating Role of Age in the Effect of Video Playback Speed on Urgency Perception in the Context of Climate Change. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148923

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheng, Xushan, Tiantian Mo, and Xinyue Zhou. 2022. "The Moderating Role of Age in the Effect of Video Playback Speed on Urgency Perception in the Context of Climate Change" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148923

APA StyleSheng, X., Mo, T., & Zhou, X. (2022). The Moderating Role of Age in the Effect of Video Playback Speed on Urgency Perception in the Context of Climate Change. Sustainability, 14(14), 8923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148923