The Efficiency of Document and Border Procedures for International Trade

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Envelopment Analysis

2.2. CRS Model

2.3. VRS Model

2.4. Scale Efficiency

2.5. Input- or Output-Oriented

2.6. Window Analysis

3. Data

3.1. Definition of Trading Partner and Mode of Transport

3.2. Output Variables

3.3. Input Variables

3.4. Reforms

3.5. Data Collection

3.6. Sample Size

4. Panel Data Analysis

4.1. Properties of Window Analysis

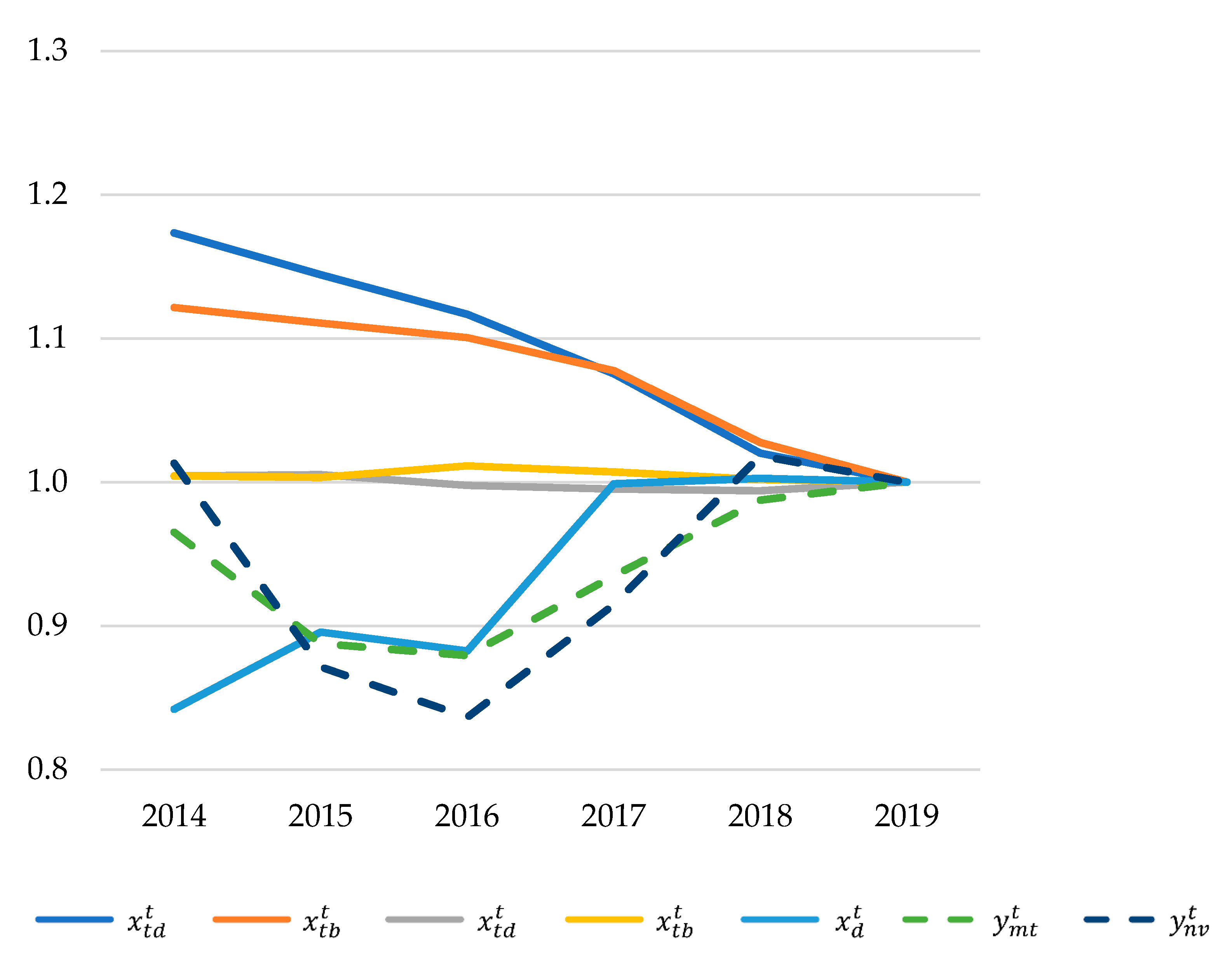

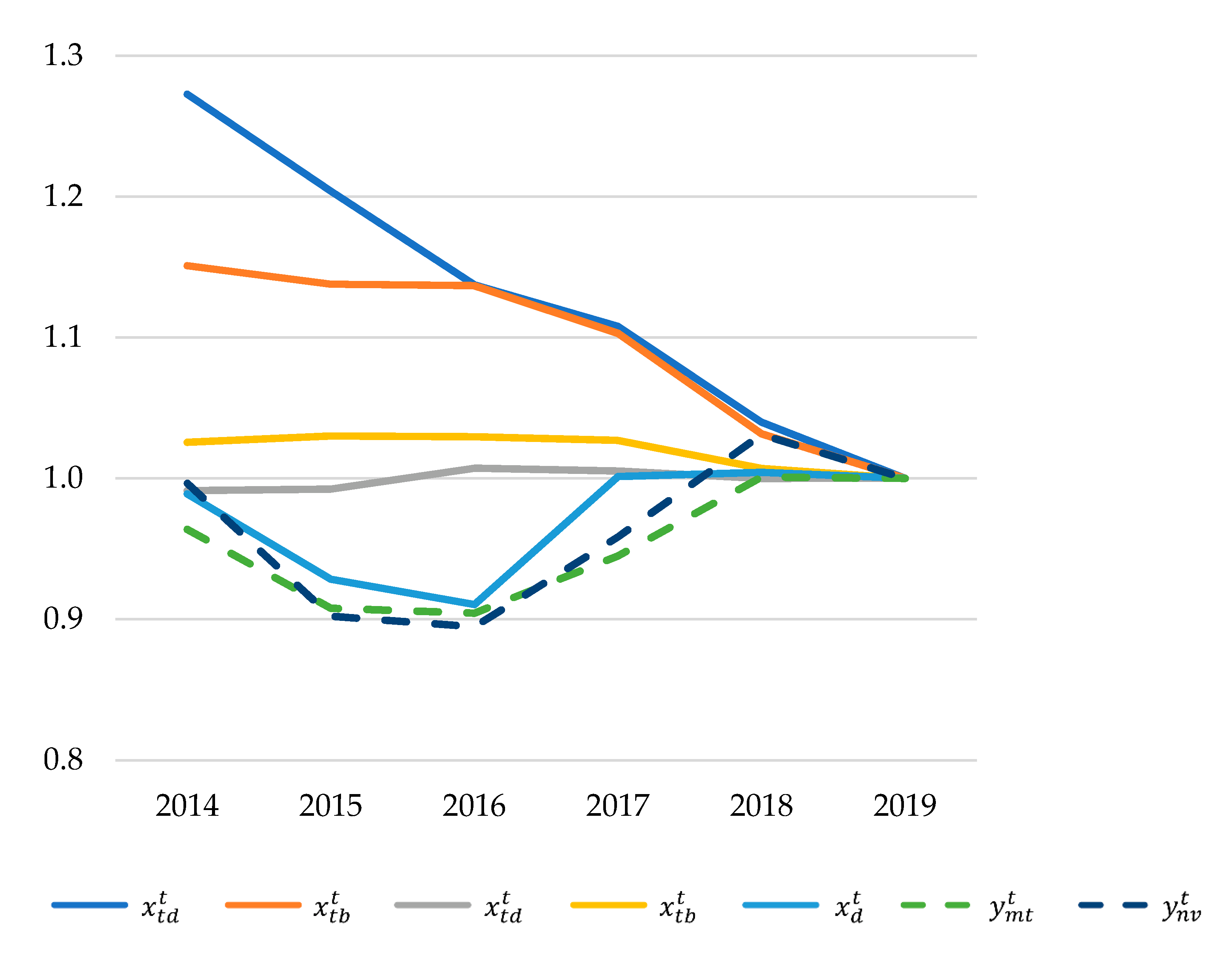

4.2. Change in Efficiency from 2014 to 2019

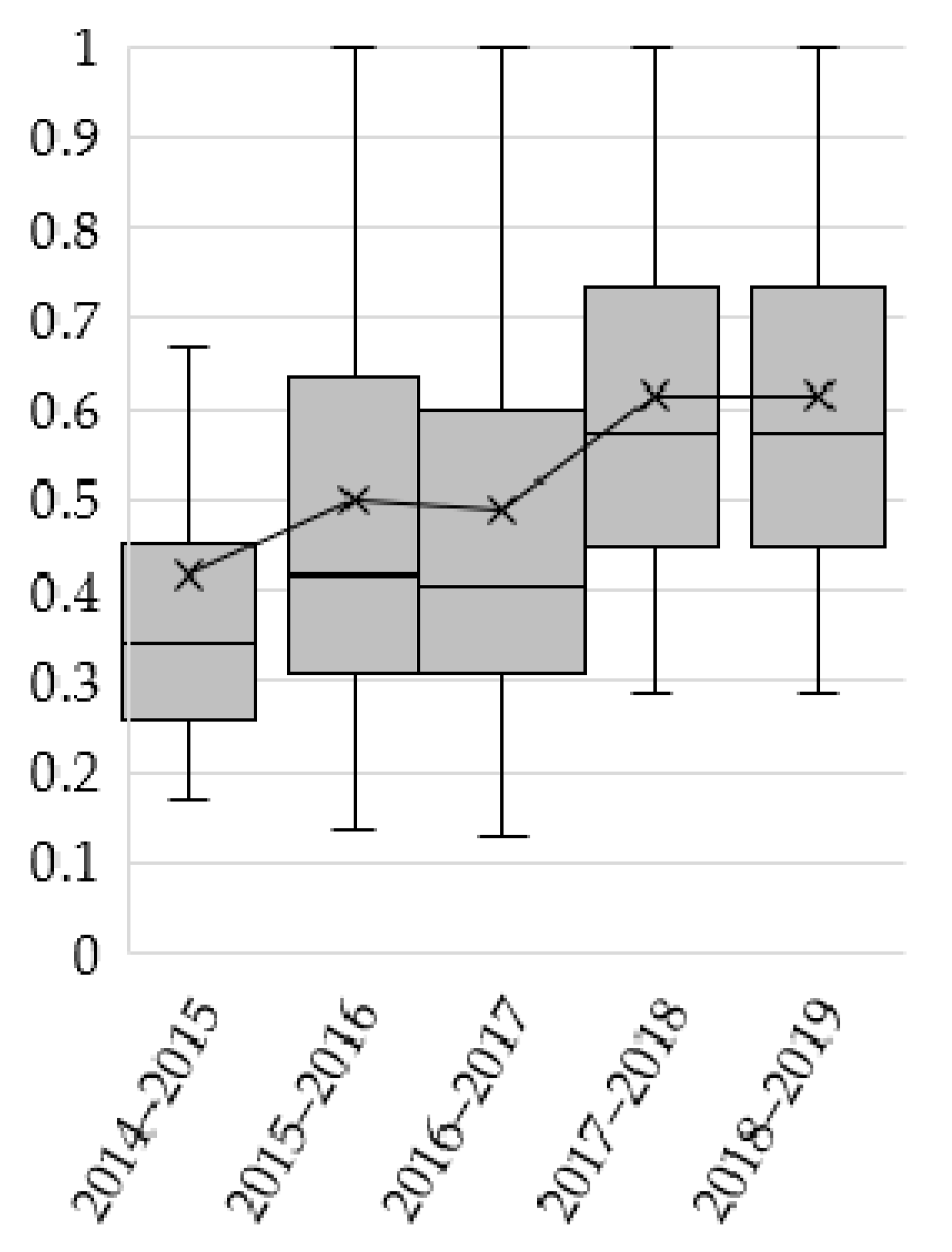

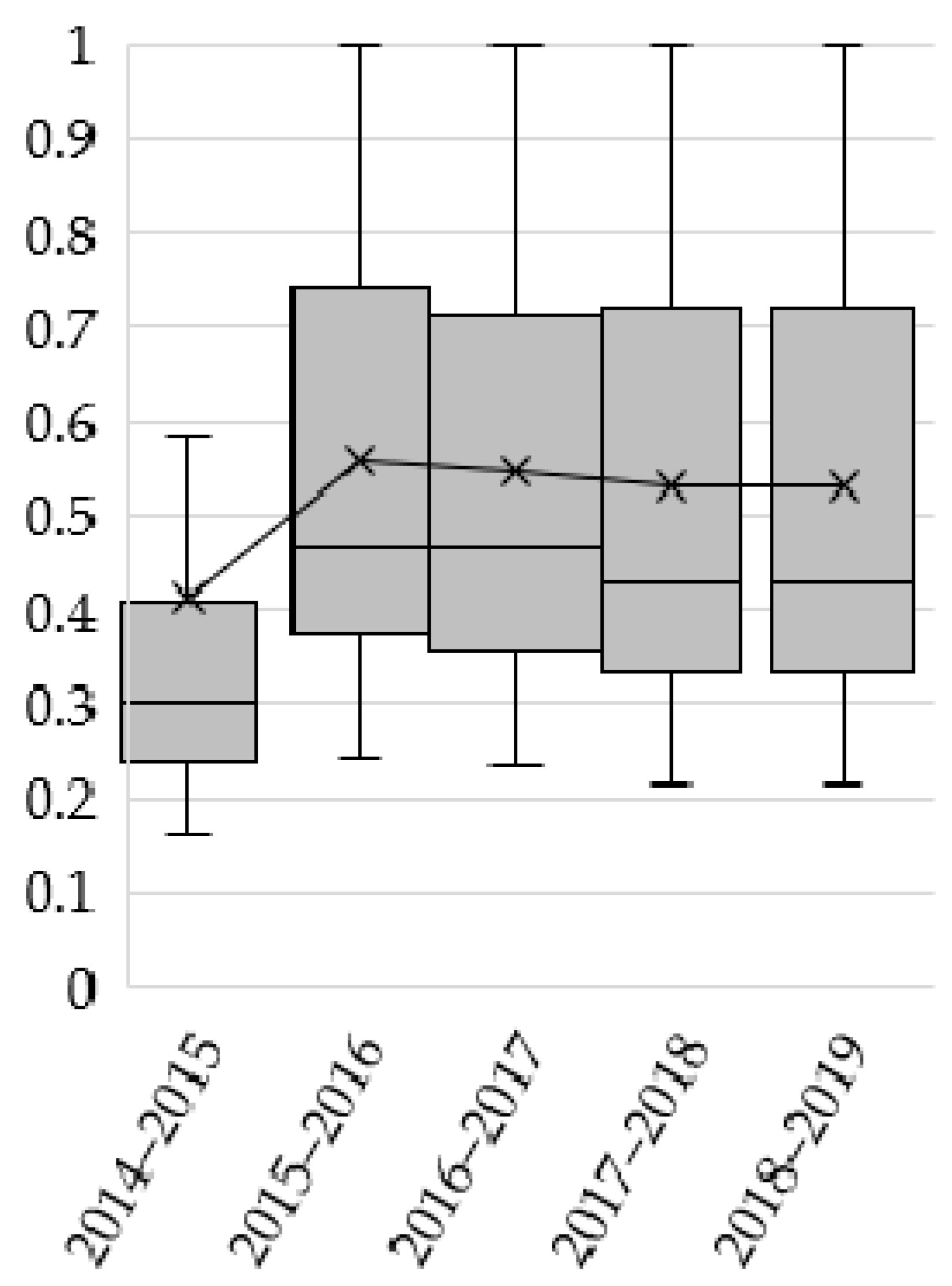

4.3. Change in Efficiency after Reforms

5. Cross-Sectional Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grainger, A. Cross-Border Logistics Operations: Effective Trade Facilitation and Border Management; Kogan Page Limited: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Doing Business Database. Available online: http://www.doingbusiness.org/data (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Martincus, V.C.; Carballo, J.; Graziano, A. Customs. J. Int. Econ. 2015, 96, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djankov, S.; Freund, C.; Pham, C. Trade on Time. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2010, 92, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, C.; Rocha, N. What Constrains Africa’s Exports? World Bank Econ. Rev. 2011, 25, 361–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portugal-Perez, A.; Wilson, S.J. Export performance and trade facilitation reform: Hard and soft infrastructure. World Dev. 2012, 40, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.F.; Dong, Q.L.; Peng, Z.M.; Khan, S.A.R.; Tarasov, A. The green logistics impact on international trade: Evidence from developed and developing countries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, P.C.; Canuto, O.; Morini, C. The Impacts of Trade Facilitation Measures on International Trade Flows. Policy Res. Work. Pap. 2015, 7367. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/22451 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- World Bank. Doing Business Reforms—Trading across Borders. 2019. Available online: https://subnational.doingbusiness.org/en/data/exploretopics/trading-across-borders/reforms (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Carballo, J.; Graziano, A.; Schaur, G.; Martincus, V.C. The Border Labyrinth: Information Technologies and Trade in the Presence of Multiple Agencies; Inter-American Development Bank: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lanz, R.; Michael, R.; Sainabou, T. Reducing trade costs in LDCs: The role of aid for trade. In WTO Working Paper; WTO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, M.J. The measurement of productive efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1957, 120, 253–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinane, K.; Wang, T.F.; Song, D.W.; Ji, P. The technical efficiency of container ports: Comparing data envelopment analysis and stochastic frontier analysis. Transp. Res. Policy Pract. 2006, 40, 354–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanou, E.H.; Wang, X. Assessment of transit transport corridor efficiency of landlocked African countries using data envelopment analysis. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2018, 114, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ishiguro, K. Measuring the efficiency of automated container terminals in China and Korea. Asian Transp. Stud. 2019, 5, 584–599. [Google Scholar]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W. Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Manag. Sci. 1984, 30, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinane, K.; Song, D.W.; Ji, P.; Wang, T. An application of DEA windows analysis to container port production efficiency. Rev. Netw. Econ. 2004, 3, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pjevčević, D.; Radonjić, A.; Hrle, Z.; Čolić, V. DEA window analysis for measuring port efficiencies in Serbia. Promet-Traffic Transp. 2012, 24, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Asmild, M.; Paradi, J.C.; Aggarwall, V.; Schaffnit, C. Combining DEA window analysis with the Malmquist index approach in a study of the Canadian banking industry. J. Prod. Anal. 2004, 21, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Doing Business Economy Profile. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/12192/discover?filtertype=dateIssued&filter_relational_operator=equals&filter=%5B2010+TO+2019%5D (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- IHS Markit. GTAS Forecasting. Available online: https://ihsmarkit.com/products/gtas-forecasting.html (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Jiang, Y.; Qiao, G.; Lu, J. Impacts of the new international land–sea trade corridor on the freight transport structure in China, Central Asia, the ASEAN countries and the EU. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2020, 35, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegmans, B.; Janic, M. Analysis, modeling, and assessing performances of supply chains served by long-distance freight transport corridors. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2019, 13, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagakos, G.; Psaraftis, H.N. Model-based corridor performance analysis—An application to a European case. Eur. J. Transp. Infrastruct. Res. 2017, 17, 225–247. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, D.; Kim, D.; Lee, E. A study on competitiveness of sea transport by comparing international transport routes between Korea and EU. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2015, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, T.; Hanaoka, S.; Nguyen, L.X. The valuation of shipment time variability in Greater Mekong Subregion. Transp. Policy 2014, 32, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, M.B.; Hanaoka, S. Assessment of intermodal transport corridors: Cases from North-East and Central Asia. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2012, 5, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Doing Business 2015: Going Beyond Efficiency; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Doing Business 2016: Measuring Regulatory Quality and Efficiency; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Doing Business 2017: Equal Opportunity for All; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Doing Business 2018: Reforming to Create Jobs; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Doing Business 2019: Training for Reform; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Doing Business 2020; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Trade Organization. World Trade Statistical Review 2016; WTO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Golany, B.A.; Roll, Y. An application procedure for DEA. Omega 1989, 17, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Swarts, J.; Thomas, D.A. An introduction to data envelopment analysis with some of its models and their uses. Res. Gov. Nonprofit Acc. 1989, 5, 125–163. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, L.; Sinuany-Stern, Z. Combining ranking scales and selecting variables in the DEA context: The case of industrial branches. Comput. Oper. Res. 1998, 25, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, R.G.; Allen, R.; Camanho, A.s.; Podinovski, V.V.; Sarrico, C.S.; Shale, E.A. Pitfalls and protocols in DEA. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2001, 132, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedraja-Chaparro, F.; Salinas-Jimenez, J.; Smith, P. On the quality of the data envelopment analysis model. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1999, 50, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, W.; Seiford, L.; Tone, K. Data Envelopment Analysis: A Comprehensive Text with Models, Applications, References and DEA-Solver Software, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 326–328. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Panel Data Analysis 2014–2019 | Cross-Sectional Analysis 2019 | Unit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Output | Trade volume | Trade volume | [MT] | ||

| Trade value | Trade value | [USD] | |||

| Input | Border procedures | Clearance and inspections | Time [hours] | ||

| Port/border handling | |||||

| Documentary procedures | Documentary procedures | ||||

| Border procedures | Clearance and inspections | Cost [USD] | |||

| Port/border handling | |||||

| Documentary procedures | Documentary procedures | ||||

| Number of documents | Number of documents | [No.] | |||

| Reform Category | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced customs administration and inspections | Export | 1 (0) | 11 (10) | 16 (11) | 28 (21) |

| Import | 1 (1) | 11 (10) | 15 (12) | 27 (23) | |

| Introduced or improved electronic submission and processing of documents | Export | 21 (18) | 18 (17) | 21 (27) | 60 (52) |

| Import | 25 (21) | 16 (15) | 19 (16) | 60 (52) | |

| Strengthened transport or port infrastructure | Export | 1 (1) | 11 (11) | 7 (7) | 19 (19) |

| Import | 3 (3) | 9 (9) | 10 (9) | 22 (21) |

| Export | Inputs | Output | |||||||

| Mean | 34 | 35 | 45 | 190 | 199 | 120 | 7.3 | 14,084,213 | 15,637,062,573 |

| Median | 10 | 24 | 24 | 134 | 170 | 85 | 7.0 | 991,376 | 1,086,768,344 |

| S.D. | 44 | 38 | 61 | 200 | 203 | 166 | 2.4 | 42,411,872 | 43,563,612,935 |

| Kurtosis | 2.9 | 11 | 19 | 13 | 3.4 | 64 | -0.2 | 33.7 | 28.3 |

| Skewness | 1.7 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 6.7 | 0.6 | 5.5 | 5.0 |

| Range | 204 | 276 | 504 | 1500 | 1200 | 1800 | 14 | 332,287,612 | 316,065,646,203 |

| Min. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 36 | 41,562 |

| Max. | 204 | 276 | 504 | 1500 | 1200 | 1800 | 10 | 332,287,576 | 316,065,604,641 |

| No. of Countries | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 |

| Import | Inputs | Output | |||||||

| Mean | 47 | 46 | 54 | 225 | 220 | 157 | 7.3 | 6,604,451 | 14,174,380,757 |

| Median | 24 | 36 | 33 | 163 | 179 | 93 | 7.0 | 851,903 | 1,687,227,298 |

| S.D. | 60 | 52 | 66 | 248 | 240 | 192 | 2.4 | 18,564,114 | 40,472,822,572 |

| Kurtosis | 6.5 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 16 | 4.6 | 6.5 | −0.5 | 50 | 30 |

| Skewness | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 6 | 5 |

| Range | 360 | 267 | 360 | 2000 | 1476 | 1025 | 14 | 174,284,734 | 316,065,646,203 |

| Min. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2640 | 10,433,061 |

| Max. | 360 | 267 | 360 | 2000 | 1476 | 1025 | 11 | 174,282,094 | 316,055,213,142 |

| No. of Countries | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 |

| Customs Administration and Inspections | Electronic Submission and Processing of Documents | Transport or Port Infrastructure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export | Before † | After ‡ | Before † | After ‡ | Before † | After ‡ |

| Mean | 0.39 | 0.57 | 0.38 | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.55 |

| Median | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.39 | 0.57 |

| S.D. | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| No. of Countries | 21 | 21 | 52 | 52 | 19 | 19 |

| p-value | p < 0.001 ** | p < 0.001 ** | p < 0.001 ** | |||

| Import | Before † | After ‡ | Before † | After ‡ | Before † | After ‡ |

| Mean | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.39 |

| Median | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.38 |

| S.D. | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.11 |

| No. of Countries | 23 | 23 | 52 | 52 | 21 | 21 |

| p-value | p = 0.778 | p = 0.002 * | p = 0.8076 | |||

| Economy | CRS | Rank | VRS | SE | Return | Economy | CRS | Rank | VRS | SE | Return |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 1.00 | 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | - | Georgia | 0.00 | 36 | 0.76 | 0.00 | drs |

| France | 1.00 | 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | - | Iceland | 0.00 | 38 | 0.75 | 0.00 | drs |

| Mexico | 1.00 | 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | - | Singapore | 0.02 | 39 | 0.73 | 0.03 | drs |

| Netherlands | 1.00 | 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | - | Japan | 0.57 | 40 | 0.73 | 0.79 | drs |

| United States | 1.00 | 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | - | Botswana | 0.03 | 41 | 0.72 | 0.04 | drs |

| Poland | 0.67 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.67 | drs | Eswatini | 0.01 | 42 | 0.72 | 0.02 | drs |

| Austria | 0.66 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.66 | drs | Taiwan, China | 0.02 | 43 | 0.71 | 0.03 | drs |

| Italy | 0.66 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.66 | drs | New Zealand | 0.03 | 44 | 0.66 | 0.04 | drs |

| Belgium | 0.53 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.53 | drs | Switzerland | 0.30 | 45 | 0.65 | 0.47 | drs |

| Germany | 0.51 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.51 | drs | Moldova | 0.00 | 46 | 0.65 | 0.00 | drs |

| Czech Republic | 0.44 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.44 | drs | Norway | 0.03 | 47 | 0.64 | 0.05 | drs |

| Kazakhstan | 0.41 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.41 | drs | North Macedonia | 0.01 | 48 | 0.62 | 0.01 | drs |

| Spain | 0.36 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.36 | drs | Namibia | 0.01 | 49 | 0.62 | 0.02 | drs |

| Sweden | 0.21 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.21 | drs | Australia | 0.06 | 50 | 0.60 | 0.11 | drs |

| Denmark | 0.18 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.18 | drs | Palau | 0.00 | 51 | 0.60 | 0.00 | drs |

| Romania | 0.16 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.16 | drs | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 0.00 | 52 | 0.59 | 0.01 | drs |

| Luxembourg | 0.12 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.12 | drs | Bahamas, The | 0.02 | 53 | 0.57 | 0.03 | drs |

| Portugal | 0.10 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.10 | drs | Bhutan | 0.01 | 54 | 0.54 | 0.02 | drs |

| Greece | 0.05 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.05 | drs | Serbia | 0.01 | 54 | 0.54 | 0.01 | drs |

| Bulgaria | 0.04 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.04 | drs | Mauritius | 0.00 | 56 | 0.53 | 0.00 | drs |

| Croatia | 0.04 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.04 | drs | Rwanda | 0.00 | 57 | 0.52 | 0.00 | drs |

| Lithuania | 0.03 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.03 | drs | Iraq | 0.04 | 58 | 0.50 | 0.08 | drs |

| Malta | 0.02 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.02 | drs | Philippines | 0.04 | 58 | 0.50 | 0.07 | drs |

| Estonia | 0.02 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.02 | drs | Marshall Islands | 0.02 | 58 | 0.50 | 0.03 | drs |

| Latvia | 0.02 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.02 | drs | Mongolia | 0.01 | 58 | 0.50 | 0.03 | drs |

| Slovenia | 0.01 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.01 | drs | Uruguay | 0.01 | 58 | 0.50 | 0.02 | drs |

| Lesotho | 0.01 | 27 | 0.98 | 0.01 | drs | Ecuador | 0.01 | 58 | 0.50 | 0.02 | drs |

| Armenia | 0.02 | 28 | 0.95 | 0.02 | drs | Antigua and Barbuda | 0.00 | 58 | 0.50 | 0.01 | drs |

| Hungary | 0.21 | 29 | 0.80 | 0.26 | drs | Costa Rica | 0.00 | 58 | 0.50 | 0.00 | drs |

| Belarus | 0.45 | 30 | 0.80 | 0.56 | drs | St. Lucia | 0.00 | 58 | 0.50 | 0.00 | drs |

| Ireland | 0.24 | 31 | 0.79 | 0.30 | drs | Solomon Islands | 0.00 | 58 | 0.50 | 0.00 | drs |

| Panama | 0.05 | 32 | 0.79 | 0.06 | drs | Nicaragua | 0.00 | 58 | 0.50 | 0.00 | drs |

| Hong Kong SAR | 0.09 | 33 | 0.78 | 0.11 | drs | Oman | 0.01 | 69 | 0.49 | 0.01 | drs |

| United Kingdom | 0.48 | 34 | 0.77 | 0.62 | drs | China | 0.39 | 70 | 0.46 | 0.83 | drs |

| Turkey | 0.08 | 35 | 0.76 | 0.10 | drs | Malaysia | 0.03 | 71 | 0.44 | 0.07 | drs |

| Cyprus | 0.00 | 36 | 0.76 | 0.01 | drs | UAE | 0.02 | 72 | 0.44 | 0.04 | drs |

| Albania | 0.00 | 73 | 0.43 | 0.00 | drs | Maldives | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.00 | drs |

| Guatemala | 0.07 | 74 | 0.43 | 0.16 | drs | St. Kitts and Nevis | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.00 | drs |

| Brazil | 0.05 | 74 | 0.43 | 0.12 | drs | Bolivia | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.00 | drs |

| Uzbekistan | 0.03 | 74 | 0.43 | 0.06 | drs | Benin | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.00 | drs |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.02 | 74 | 0.43 | 0.04 | drs | Mauritania | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.00 | drs |

| Israel | 0.01 | 74 | 0.43 | 0.03 | drs | Comoros | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.00 | drs |

| Barbados | 0.00 | 74 | 0.43 | 0.01 | drs | Lao PDR | 0.02 | 114 | 0.35 | 0.06 | drs |

| East Timor | 0.00 | 74 | 0.43 | 0.00 | drs | Russia | 0.05 | 115 | 0.34 | 0.13 | drs |

| Bahrain | 0.00 | 74 | 0.43 | 0.00 | drs | Colombia | 0.10 | 116 | 0.33 | 0.29 | drs |

| Brunei | 0.00 | 74 | 0.43 | 0.00 | drs | Indonesia | 0.04 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.11 | drs |

| Grenada | 0.00 | 74 | 0.43 | 0.00 | drs | Cambodia | 0.03 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.09 | drs |

| Equatorial Guinea | 0.00 | 74 | 0.43 | 0.00 | drs | Peru | 0.03 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.09 | drs |

| St. Vincent and the Grenadines | 0.00 | 74 | 0.43 | 0.00 | drs | Argentina | 0.02 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.06 | drs |

| Vanuatu | 0.00 | 74 | 0.43 | 0.00 | drs | Morocco | 0.02 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.05 | drs |

| Seychelles | 0.00 | 74 | 0.43 | 0.00 | drs | Haiti | 0.01 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.02 | drs |

| Thailand | 0.08 | 88 | 0.42 | 0.20 | drs | Kuwait | 0.00 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.01 | drs |

| Ukraine | 0.13 | 89 | 0.38 | 0.34 | drs | Senegal | 0.00 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.01 | drs |

| Chile | 0.10 | 90 | 0.38 | 0.28 | drs | Madagascar | 0.00 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.01 | drs |

| Vietnam | 0.05 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.13 | drs | Cape Verde | 0.00 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.01 | drs |

| Honduras | 0.03 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.09 | drs | Congo, D.R. | 0.00 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.01 | drs |

| Jamaica | 0.02 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.05 | drs | Lebanon | 0.00 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.00 | drs |

| Paraguay | 0.01 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.03 | drs | Gabon | 0.00 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.00 | drs |

| Libya | 0.01 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.02 | drs | Congo, Rep. | 0.00 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.00 | drs |

| Tunisia | 0.01 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.02 | drs | Chad | 0.00 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.00 | drs |

| Papua New Guinea | 0.01 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.02 | drs | Burkina Faso | 0.00 | 117 | 0.33 | 0.00 | drs |

| Guinea | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.01 | drs | Tajikistan | 0.00 | 133 | 0.33 | 0.01 | drs |

| Djibouti | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.01 | drs | El Salvador | 0.02 | 134 | 0.32 | 0.06 | drs |

| Qatar | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.01 | drs | Ethiopia | 0.00 | 135 | 0.32 | 0.00 | drs |

| Guyana | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.01 | drs | Malawi | 0.00 | 136 | 0.31 | 0.00 | drs |

| Sri Lanka | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.01 | drs | Bangladesh | 0.07 | 137 | 0.30 | 0.23 | drs |

| Belize | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.01 | drs | Nepal | 0.07 | 138 | 0.30 | 0.23 | drs |

| Cameroon | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.00 | drs | India | 0.05 | 138 | 0.30 | 0.16 | drs |

| Jordan | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.00 | drs | Myanmar | 0.04 | 138 | 0.30 | 0.12 | drs |

| Suriname | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.00 | drs | Tanzania | 0.01 | 138 | 0.30 | 0.02 | drs |

| Guinea-Bissau | 0.00 | 91 | 0.38 | 0.00 | drs | Pakistan | 0.00 | 138 | 0.30 | 0.01 | drs |

| Angola | 0.00 | 138 | 0.30 | 0.01 | drs | Ghana | 0.00 | 151 | 0.27 | 0.00 | drs |

| Kenya | 0.00 | 138 | 0.30 | 0.01 | drs | Togo | 0.00 | 151 | 0.27 | 0.00 | drs |

| Dominica | 0.00 | 138 | 0.30 | 0.01 | drs | Afghanistan | 0.00 | 151 | 0.27 | 0.00 | drs |

| Fiji | 0.00 | 138 | 0.30 | 0.01 | drs | Central African Rep. | 0.00 | 151 | 0.27 | 0.00 | drs |

| Mali | 0.00 | 138 | 0.30 | 0.00 | drs | Burundi | 0.00 | 157 | 0.25 | 0.00 | drs |

| Sierra Leone | 0.00 | 138 | 0.30 | 0.00 | drs | Cote d’Ivoire | 0.00 | 158 | 0.23 | 0.01 | drs |

| Sudan | 0.00 | 138 | 0.30 | 0.00 | drs | Liberia | 0.00 | 158 | 0.23 | 0.01 | drs |

| Mozambique | 0.05 | 150 | 0.29 | 0.16 | drs | Trinidad and Tobago | 0.00 | 158 | 0.23 | 0.00 | drs |

| Algeria | 0.02 | 151 | 0.27 | 0.09 | drs | South Sudan | 0.00 | 158 | 0.23 | 0.00 | drs |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 0.00 | 151 | 0.27 | 0.01 | drs | Uganda | 0.00 | 162 | 0.21 | 0.00 | drs |

| Group | Country | VRS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | France | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Netherlands | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Kazakhstan | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Austria | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Belgium | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Bulgaria | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Croatia | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Czech Republic | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Denmark | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Estonia | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Germany | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Greece | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Italy | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Latvia | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Lithuania | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Luxembourg | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Poland | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Portugal | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Romania | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Slovenia | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Spain | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Sweden | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 1 | Mexico | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| 1 | Lesotho | 0.98 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.95 |

| 1 | Hungary | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Belarus | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Ireland | 0.79 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| 1 | New Zealand | 0.66 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| 1 | Switzerland | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.95 |

| 1 | Moldova | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.95 |

| 1 | Palau | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Antigua and Barbuda | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Costa Rica | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Ecuador | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Iraq | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Marshall Islands | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Mongolia | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Nicaragua | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Philippines | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Solomon Islands | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | St. Lucia | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Uruguay | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | China | 0.46 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| 1 | Bahrain | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Barbados | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Brazil | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Brunei | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Equatorial Guinea | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Grenada | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Guatemala | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Israel | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Saudi Arabia | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Seychelles | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | St. Vincent and the Grenadines | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | East Timor | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Uzbekistan | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Vanuatu | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Ukraine | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Chile | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Belize | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Benin | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Bolivia | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Cameroon | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Comoros | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Djibouti | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Guinea | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Guinea-Bissau | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Guyana | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Honduras | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Jamaica | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Jordan | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Libya | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Maldives | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Mauritania | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Papua New Guinea | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Paraguay | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Qatar | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Sri Lanka | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | St. Kitts and Nevis | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Suriname | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Tunisia | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Vietnam | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Russia | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Colombia | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Argentina | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Burkina Faso | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Cape Verde | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Cambodia | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Chad | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Congo, D.R. | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Congo, Rep. | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Gabon | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Haiti | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Indonesia | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Kuwait | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Lebanon | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Madagascar | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Morocco | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Peru | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Senegal | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Bangladesh | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Angola | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Dominica | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Fiji | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | India | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Kenya | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Mali | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Myanmar | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Nepal | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Pakistan | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Sierra Leone | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Sudan | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Tanzania | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Afghanistan | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Algeria | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Central African Rep. | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Egypt, Arab Rep. | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Ghana | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Togo | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Burundi | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Cote d’Ivoire | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Liberia | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | South Sudan | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Trinidad and Tobago | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | Uganda | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | Armenia | 0.95 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Panama | 0.79 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| 2 | Hong Kong SAR | 0.78 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | United Kingdom | 0.77 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Turkey | 0.76 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Cyprus | 0.76 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Georgia | 0.76 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Iceland | 0.75 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Singapore | 0.73 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Japan | 0.73 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Botswana | 0.72 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Eswatini | 0.72 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Taiwan, China | 0.71 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Norway | 0.64 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | North Macedonia | 0.62 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Namibia | 0.62 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Australia | 0.60 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | Bahamas, The | 0.57 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| 2 | Serbia | 0.54 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.92 |

| 2 | Bhutan | 0.54 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| 2 | Mauritius | 0.53 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| 2 | Oman | 0.49 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| 2 | Malaysia | 0.44 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | UAE | 0.44 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.70 |

| 2 | Thailand | 0.42 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | El Salvador | 0.32 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| 2 | Mozambique | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| 3 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 0.59 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 3 | Rwanda | 0.52 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| 3 | Albania | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 3 | Lao PDR | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 3 | Tajikistan | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 3 | Ethiopia | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 3 | Malawi | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| 4 | Canada | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.40 |

| 4 | United States | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| 5 | Malta | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hiraide, T.; Hanaoka, S.; Matsuda, T. The Efficiency of Document and Border Procedures for International Trade. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8913. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148913

Hiraide T, Hanaoka S, Matsuda T. The Efficiency of Document and Border Procedures for International Trade. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8913. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148913

Chicago/Turabian StyleHiraide, Takashi, Shinya Hanaoka, and Takuma Matsuda. 2022. "The Efficiency of Document and Border Procedures for International Trade" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8913. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148913

APA StyleHiraide, T., Hanaoka, S., & Matsuda, T. (2022). The Efficiency of Document and Border Procedures for International Trade. Sustainability, 14(14), 8913. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148913