Paths to Promote the Sustainability of Kindergarten Teachers’ Caring: Teachers’ Perspectives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Education for Sustainable Development in ECE

2.2. Teachers’ Caring in ECE

2.3. Strategies to Promote Teachers’ Caring

2.4. Theoretical Framework

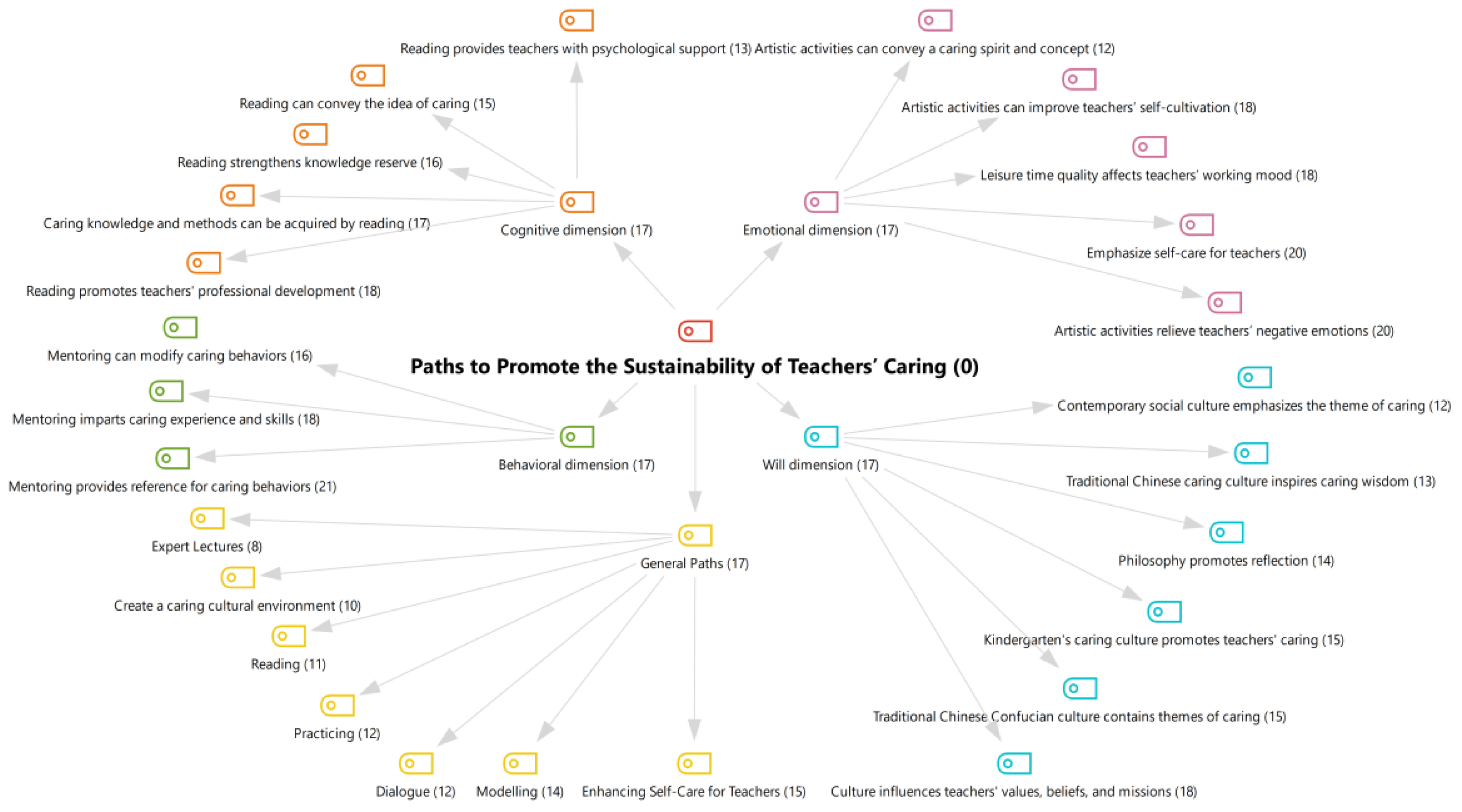

2.5. Analytical Framework: Cognition, Emotion, Will, and Behavior

- What paths can promote the sustainability of teachers’ caring from the perspective of kindergarten teachers? What are the forms/techniques of these paths?

- What path can be used to promote the sustainability of teachers’ caring in the cognitive, emotional, will, and behavioral dimensions? What are the impacts on this path?

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Participants

3.3. Interview Structure

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Reading Provides Caring Skills and Methods to Support Teachers with Knowledge

Many picture books that depict caring show me where caring comes from and how to express it […]. The knowledge of caring that I learn through interacting with my child allows me to experience caring and pass it on to the school children (Teacher A).

4.2. Leisure and Art Regulate Work Mood to Support Teachers with Caring Emotions

My leisure time is abundant, so I feel confident about my work […]. If a teacher is in a good mood, the children will be happy. If a teacher is under pressure every day, their suppressed emotions will be passed on to the children.

4.3. Culture Promotes Review and Reflection to Support Teachers with Caring Beliefs

Philosophy is like reflection. My philosophy is to make children better, so every child receives my care. This has always been the same. As long as I respect my philosophy, my teaching will not hurt children and love can keep us going.

Caring is the energy that people export to the outside world, and the dialectical thinking that philosophy brings to people can help their inner mind export energy after becoming stable and consistent […]. In the process of philosophical thinking, we constantly accumulate more energy to radiate to others (Teacher F).

A teacher who works in a kindergarten full of love and care must be concerned with the quality of caring […]. Everyone gets fair and satisfactory care, and the teacher will care more for their students.

4.4. Mentoring Provides Model Experiences to Support Teachers with Behavioral Reference

When I first started my internship in a kindergarten, the type of care was similar to spoiling. It was like [giving the children] unconditional satisfaction. Later, I learned a more reasonable way of caring for children from an experienced teacher who is my partner.

Caring is based on observations and understanding, and this is the first step. Only when you understand what the child needs are you able to act with care […]. The second step is determining how many ways you have to express your caring […]. How much energy do you have to accurately convey that you care to them? […] You have to understand and convey it. Novice teachers […] care for their children, but they don’t know what kind of care the children want […]. As experienced teachers are relatively skilled, they can correctly understand children and give them more suitable care.

5. Discussion

5.1. Reading Promotes the Sustainability of Caring Cognition and Awakens the Conscience

5.2. Leisure and Art Activities Promote the Sustainability of Caring Emotion

5.3. Cultural Immersion Promotes the Sustainability of Caring Will and Cultivates Beliefs

5.4. Mentoring Practice Promotes the Sustainability of Caring Behaviors

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Basic information |

Prescribed kindergarten and working context

|

| General paths to promote the sustainability of kindergarten teachers’ caring |

|

| If the participants reported some promotion paths in caring, they were invited to specify them (e.g., forms and techniques). |

| Forms and techniques |

|

| Prompts |

| If participants did not provide more information, the researcher used the following prompts based on the original four dimensions of the teachers’ caring promotion model: |

| The cognitive dimension |

|

| The emotional dimension |

|

| The will dimension |

|

| The behavioral dimension |

|

References

- Engdahl, I. Early childhood education for sustainability: The OMEP world project. Int. J. Early Child. 2015, 47, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ärlemalm-Hagsér, E.; Pramling Samuelsson, I. Early childhood education and acre for sustainability–Historical context and current challenges. In Early Childhood Care and Education for Sustainability; Huggins, V., Evans, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Furu, A.C.; Heilala, C. Sustainability Education in Progress: Practices and Pedagogies in Finnish Early Childhood Education and Care Teaching Practice Settings. Int. J. Early Child. Environ. Educ. 2021, 8, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hedefalk, M.; Almqvist, J.; Östman, L. Education for sustainable development in early childhood education: A review of the research literature. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 975–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kim, H.; Yu, S. Perceptions and attitudes of early childhood teachers in Korea about education for sustainable development. Int. J. Early Child. 2016, 48, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, A. A posthumanist perspective on caring in early childhood teaching. N. Z. J. Educ. Stud. 2019, 54, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Han, L.; Yang, F.; Gao, L. The evolution of sustainable development theory: Types, goals, and research prospects. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mutalimov, V.; Kovaleva, I.; Mikhaylov, A.; Stepanova, D. Assessing regional growth of small business in Russia. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2021, 9, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushukina, V. Specific Features of Renewable Energy Development in the World and Russia. Financ. J. 2021, 5, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranina, E.I. China on the way to achieving carbon neutrality. Financ. J. 2021, 5, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseev, N.; Mikhaylov, A.; Varyash, I.; Saqib, A. Investigating the relation of GDP per capita and corruption index. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveeva, N. Legislative Regulation Financial Statement Preparation by Micro Entities: International Experience. Financ. J. 2021, 5, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, J. Sustainability education and teacher education: Finding a natural habitat? Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2012, 28, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj-Blatchford, J. Editorial: Education for sustainable development in early childhood. Int. J. Early Child. 2009, 41, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Guidelines and recommendations for reorienting teacher education to address sustainability. In UNESCO Education for Sustainable Development in Action; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez, A.; West, R.; Graham, C.; Osguthorpe, R. Developing caring relationships in schools: A review of the research on caring and nurturing pedagogies. Rev. Educ. 2013, 1, 162–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raivio, M.; Skaremyr, E.; Kuusisto, A. Caring for worldviews in early childhood education: Theoretical and analytical tool for socially sustainable communities of care. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Määttä, K.; Hyvärinen, S.; Äärelä, T.; Uusiautti, S. Five basic cornerstones of sustainability education in the Arctic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mayseless, O. The Caring Motivation: An Integrated Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, E.K.; Birmingham, S.M. Caring relationships as a protective factor for at-risk youth: An ethnographic study. Fam. Soc. J. Contemp. Soc. Serv. 2003, 84, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan-Jensen, J.; Smith, D.M.; Blake, J.J.; Keith, V.M.; Willson, V.K. Breaking the cycle of child maltreatment and intimate partner violence: The effects of student gender and caring relationships with teachers. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2020, 29, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J.; Frost, J.; Gotch, C.; McDuffie, A.R.; Austin, B.; French, B. Teachers’ role in students’ learning at a project-based STEM high school: Implications for teacher education. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2021, 1, 1103–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cekaite, A.; Bergnehr, D. Affectionate touch and care: Embodied intimacy, compassion and control in early childhood education. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2018, 26, 940–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teven, J.J. Teacher temperament: Correlates with teacher caring, burnout, and organizational outcomes. Commun. Educ. 2007, 56, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, S.; Naama-Ghanayim, E. Why care about caring? Linking teachers’ caring and sense of meaning at work with students’ self-esteem, well-being, and school engagement. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 91, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldemariam, K.; Chan, A.; Engdahl, I.; Samuelsson, I.P.; Katiba, T.C.; Habte, T.; Muchanga, R. Care and Social Sustainability in Early Childhood Education: Transnational Perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, C.I.; Mtyuda, P.N. Teacher job dissatisfaction: Implications for teacher sustainability and social transformation. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2017, 19, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Pato, C.; Torres-Soto, N. Testing a tridimensional model of sustainable behavior: Self-care, caring for others, and caring for the planet. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 12867–12882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fopka-Kowalczyk, M.; Krajnik, M. Expectations and self-care of family members in palliative care. The analysis of needs and workshop plan. Przegląd Badań Eduk. Educ. Stud. Rev. 2019, 2, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tobón, O. El autocuidado, una habilidad para vivir [Self-care, a skill for living]. Hacia Promoc. Salud 2015, 8, 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rabin, C. “I already know I care!”: Illuminating the complexities of care practices in early childhood and teacher education. In Theorizing Feminist Ethics of Care in Early Childhood Practice: Possibilities and Dangers; Langford, R., Ed.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2019; pp. 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, T. Starting with the end in mind: Ethics-of-care-based teacher education. Counterpoints 2009, 334, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lampert, M.; Franke, M.L.; Kazemi, E.; Ghousseini, H.; Turrou, A.C.; Beasley, H.; Crowe, K. Keeping it complex: Using rehearsals to support novice teacher learning of ambitious teaching. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 64, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Fabrykowski, D.; Caldwell, P. Developing a caring attitude in the early childhood pre-service teachers. Education 2002, 123, 358–364. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, J.L.; Durlak, J.A.; Weissberg, R.P. An update on social and emotional learning outcome research. Phi Delta Kappan 2018, 100, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rabin, C.; Smith, G. Teaching care ethics: Conceptual understandings and stories for learning. J. Moral Educ. 2013, 42, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanger, M.; Osguthorpe, R. The Moral Work of Teaching and Teacher Education: Preparing and Supporting Practitioners; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schussler, D.; Knarr, L. Building awareness of dispositions: Enhancing moral sensibilities in teaching. J. Moral Educ. 2013, 42, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramberg, J.; Låftman, S.B.; Almquist, Y.B.; Modin, B. School effectiveness and students’ perceptions of teacher caring: A multilevel study. Improv. Sch. 2019, 22, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narinasamy, I.; Mamat, W.H.W. Caring teacher in developing empathy in moral education. Malays. Online J. Educ. Sci. 2018, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Louis, K.S.; Murphy, J.; Smylie, M. Caring leadership in schools: Findings from exploratory analyses. Educ. Adm. Q. 2016, 52, 310–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.Y. The connotation of sustainable development theory: Commemorating the 20th anniversary of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio. China’s Popul. Resour. Environ. 2012, 22, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings, N. Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, L.M.; Ennis, C.D. The ethic of care in teaching: An overview of supportive literature. Quest 2005, 57, 392–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noddings, N. Starting at Home: Caring and Social Policy; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings, N. Educating Moral People: A Caring Alternative to Character Education; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings, N. The Challenge to Care in Schools: An Alternative Approach to Education; Yu, T., Translator; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baice, T.; Fonua, S.M.; Levy, B.; Allen, J.M.; Wright, T. How do you (demonstrate) care in an institution that does not define ‘care’? Pastor. Care Educ. 2021, 39, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, M. The practice of pastoral care of teachers: A summary analysis of published outlines. Pastor. Care Educ. 2010, 28, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, P. Attachment theory, teacher motivation pastoral care: A challenge for teachers and academics. Pastor. Care Educ. 2013, 31, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Gergely, G.; Jurist, E.L.; Target, M. Affect Regulation, Mentalization, and the Development of the Self; Other Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, G.X. Love and education love. J. Teach. Manag. 2014, 36, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. The unification of “informed, intentional and action” in the permeable engineering ethics teaching. Mod. Univ. Educ. 2011, 4, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.A. Theoretical premise of “four-in-one” cultivation education—Based on the conceptual distinction of cognition, emotion, will and behavior. Univ. Educ. 2017, 11, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Analytical framework for realization of individual political socialization—unification of cognition, emotion, will and behavior. J. Party Sch. Taiyuan Munic. Comm. Communist Party China 2014, 1, 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y. Improving the acceptance effect of ideological and political education under the guidance of the relationship between knowledge, emotion, intention and behavior. High. Agric. Educ. 2006, 4, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- French-Lee, S.; Dooley, C.M. An exploratory qualitative study of ethical beliefs among early childhood teachers. Early Child. Educ. J. 2015, 43, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S. Qualitative interviewing techniques and styles. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Health Research; Bourgeault, I., Dingwall, R., de Vries, R., Eds.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 307–326. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.D.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, C.; Gleaves, A. Constructing the caring higher education teacher: A theoretical framework. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 54, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yıldırım, A.; Şimşek, H. Nitel Araştırma Yöntemleri, 7th ed.; Seçkin Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tutty, L.M.; Rothery, R.M.; Grinnell, J.R. Analyzing Your Own Data, Qualitative Research for Social Workers; Allyn and Bacon: Calgary, AB, Canada, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Karasar, N. Bilimsel Araştırma Yöntemi; Nobel Yayın Dağıtım: Ankara, Turkey, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, M. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.G.; Wang, Q. Some problems in the study of reading culture. Libr. Inf. Knowl. 2004, 5, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.Y. Reading literary classics and developing students’ harmonious personality. J. Shandong Educ. Inst. 2015, 6, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, M. Leisure life and the promotion of teachers’ virtue. Educ. Sci. Res. 2010, 3, 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.X. On teachers’ leisure strategy. Educ. Sci. Forum 2007, 4, 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- González, C. Valores Sociales de la Actividad Físico-Deportiva en la Cultura Del Ocio. In Sociedad del Conocimiento, Ocio y Cultura: Un Enfoque Interdisciplinar, 1st ed.; Moral, M.E., Ed.; KRK: Oviedo, Spain, 2004; pp. 363–374. ISBN 84-96119-62-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mastandrea, S.; Fagioli, S.; Biasi, V. Art and psychological well-being: Linking the brain to the aesthetic emotion. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, B.Y. Art aesthetic education and college student personality molding. J. Guizhou Univ. 2008, 2, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt, G.M. A place for emotions in behavior systems research. Behav. Processes 2019, 6, 103881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, R. Reason, emotion, and the problem of world poverty: Moral sentiment theory and international ethics. Int. Theory 2011, 3, 143–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, C.Q. The historical evolution and reflection of the culture of caring for children in China. Early Educ. Educ. Res. Ed. 2017, 2, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, G. Theoretical investigation of cultural education in the new era. Party Build. Ideol. Educ. Sch. 2019, 5, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.L. The value and approach of kindergarten teachers’ learning general knowledge. Stud. Presch. Educ. 2015, 5, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.H. The cultural construction of modern kindergarten. Jiangnan Forum 2003, 5, 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mergler, A.; Curtis, E.; Spooner-Lane, R. Teacher educators embrace philosophy: Reflections on a new way of looking at preparing pre-service teachers. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2009, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Q.N. Conceptual analysis and realization approach of sustainable development of kindergarten teachers. J. Chengdu Norm. Univ. 2021, 37, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.Z.; Wang, S.X.; Liu, Y. An analysis of the growth process and influencing factors of post-80s excellent kindergarten teachers. Theory Pract. Contemp. Educ. 2019, 2, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldhaber, D.; Krieg, J.; Theobald, R. Effective like me? Does having a more productive mentor improve the productivity of mentees? Labour Econ. 2020, 63, 101–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | - | - |

| Female | 15 | 88.24 |

| Male | 2 | 11.76 |

| Age (in years) | - | - |

| ≤30 | 12 | 70.59 |

| >30 | 5 | 29.40 |

| Teaching years | - | -- |

| ≤10 | 12 | 70.59 |

| >10 | 5 | 29.40 |

| Daily working hours | - | - |

| Eight hours | 8 | 47.10 |

| Over eight hours | 9 | 52.90 |

| Views | f |

|---|---|

| Caring knowledge and methods can be acquired by reading | 17 |

| Reading can convey the idea of caring | 15 |

| Reading promotes teachers’ professional development | 18 |

| Reading provides teachers with psychological support | 13 |

| Reading strengthens knowledge reserve | 16 |

| Total | 79 |

| Views | f |

|---|---|

| Artistic activities can convey a caring spirit and concept | 12 |

| Artistic activities can improve teachers’ self-cultivation | 18 |

| Artistic activities relieve teachers’ negative emotions | 20 |

| Emphasize self-care for teachers | 20 |

| Leisure time quality affects teachers’ working mood | 18 |

| Total | 88 |

| Views | f |

|---|---|

| Contemporary social culture emphasizes the theme of caring | 12 |

| Culture influences teachers’ values, beliefs, and missions | 18 |

| Kindergarten’s caring culture promotes teachers’ caring | 15 |

| Philosophy promotes reflection | 14 |

| Traditional Chinese Confucian culture contains themes of caring | 15 |

| Traditional Chinese caring culture inspires caring wisdom | 13 |

| Total | 87 |

| Views | f |

|---|---|

| Mentoring can modify caring behaviors | 16 |

| Mentoring imparts caring experience and skills | 18 |

| Mentoring provides a reference for caring behaviors | 21 |

| Total | 55 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, X.; Sha, T. Paths to Promote the Sustainability of Kindergarten Teachers’ Caring: Teachers’ Perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8899. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148899

Liu J, Jiang Y, Zhang B, Zhu X, Sha T. Paths to Promote the Sustainability of Kindergarten Teachers’ Caring: Teachers’ Perspectives. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8899. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148899

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jiawei, Yong Jiang, Beibei Zhang, Xingjian Zhu, and Tianyan Sha. 2022. "Paths to Promote the Sustainability of Kindergarten Teachers’ Caring: Teachers’ Perspectives" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8899. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148899

APA StyleLiu, J., Jiang, Y., Zhang, B., Zhu, X., & Sha, T. (2022). Paths to Promote the Sustainability of Kindergarten Teachers’ Caring: Teachers’ Perspectives. Sustainability, 14(14), 8899. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148899