What Is the Operation Logic of Cultivated Land Protection Policies in China? A Grounded Theory Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Mismatch between Cultivated Land Resource Value and Cultivated Land Protection Path

2.2. Imbalance between Cultivated Land Protection Policy Objectives and Stakeholders

2.3. Structural Contradiction between Restraint Mechanism and Incentive Mechanism of Cultivated Land Protection

2.4. There Are Deficiencies in the Compensation Mechanism for Cultivated Land Protection

3. Research and Data Source

3.1. Research Method

3.2. Data Sources

4. Data analysis

4.1. Open Coding

4.2. Axial Coding

4.3. Selective Coding

4.4. Theoretical Saturation Test

5. Discussion

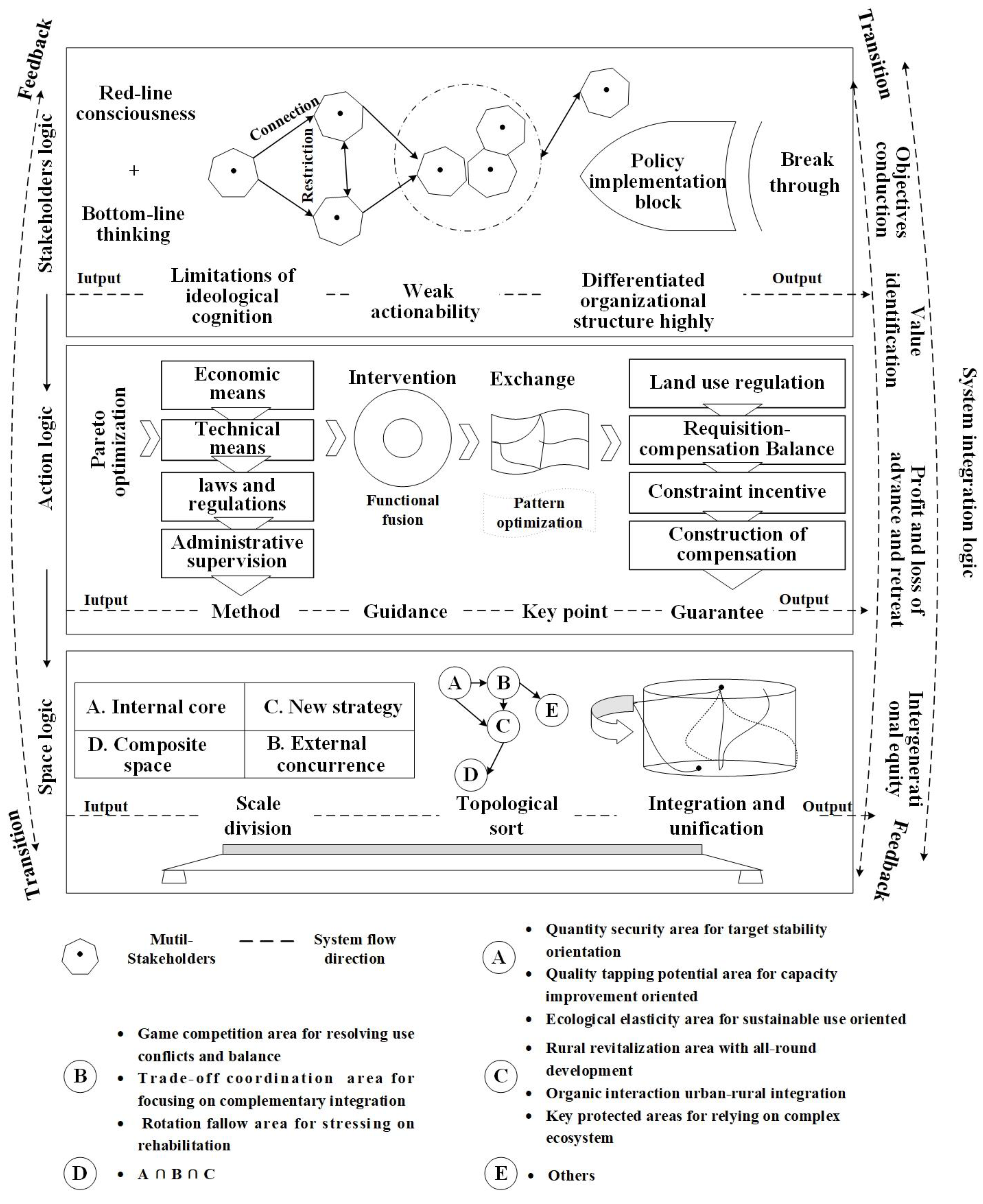

5.1. Stakeholders Logic

5.2. Action Logic

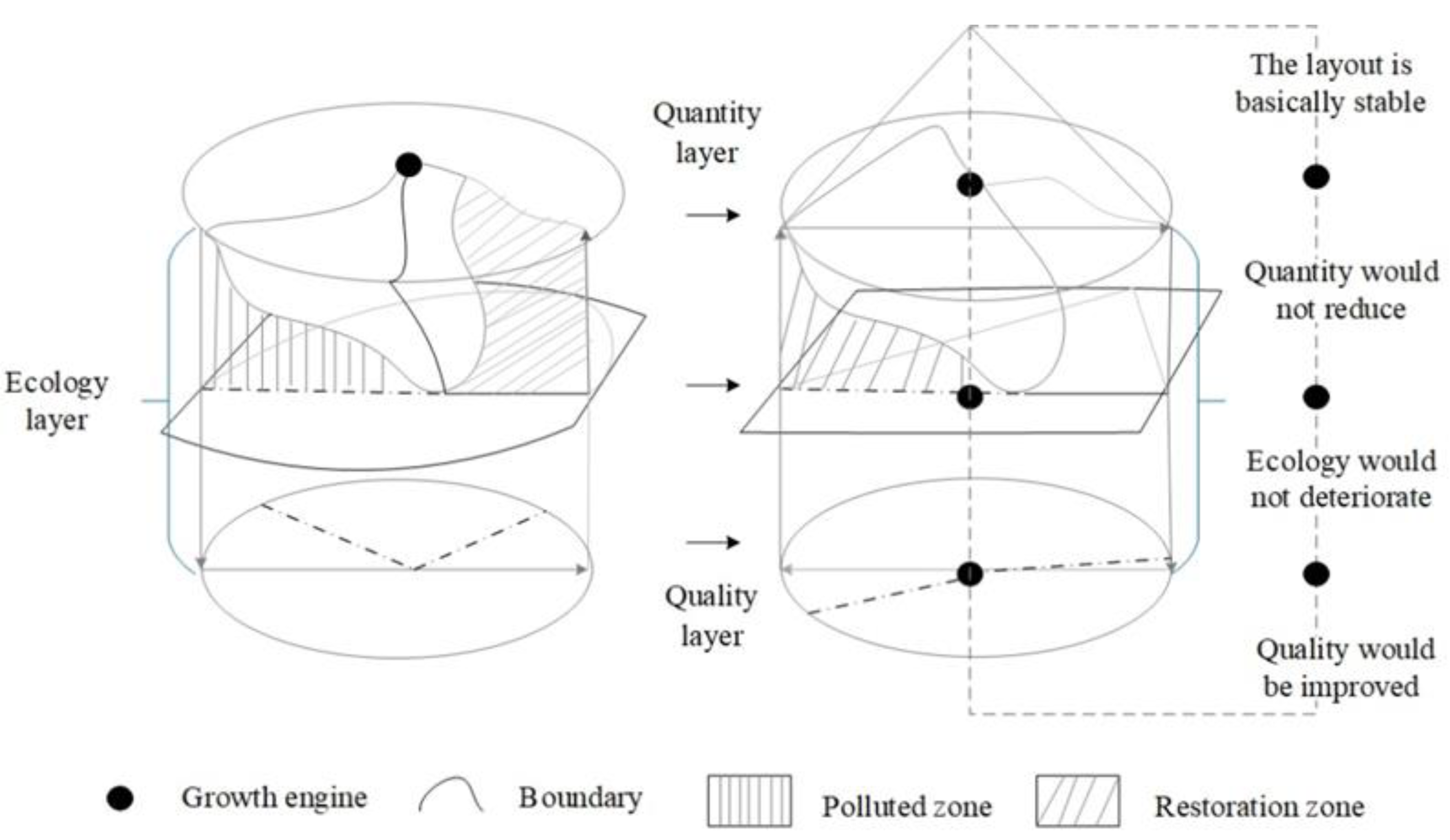

5.3. Space Logic

5.4. Systematic Integration Logic of Stakeholders–Action–Space

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The basic logic of the CLPP operation is to take the ultimate goal of cultivated land protection as the logical starting point and red-line consciousness and bottom-line thinking as the motivation. Based on a structure of government leadership with farmers as the main body and with social participation, this policy takes Pareto optimization of resource elements as the main direction. Multiple measures, such as the economy, technology, laws and regulations, and administrative supervision stimulate the functional integration of cultivated land use system. Then, relying on the internal core space, external competition and cooperation space, composite space, and new strategic space, the spatial pattern of cultivated land protection is optimized. The three dimensions of subject, action, and space are intertwined, embedded, and coupled in the input–conversion–output–feedback, and the conflict and bridging of different spaces become the inexhaustible driving force for the development of a cultivated land protection system. Therefore, we believe that the key to guaranteeing the effectiveness of CLPP in the future lies in solving the contradiction between theoretical abstraction and practical execution. Accordingly, we should distinguish the policy types and implementation methods of command control, economic incentive, and publicity guidance. In different stages of economic and social development, the optimization and combination of multiple policy tools should be reasonably used to ensure the effect of cultivated land protection. Moreover, in order to reduce the negative externality of cultivated land occupation, we should appropriately increase the comprehensive cost of converting cultivated land into construction land, and improve the efficiency of optimal allocation of land resources through land marketization measures. At the same time, land marketization measures should also be taken to improve the efficiency of optimal allocation of land resources.

- (2)

- CLPP is a comprehensive system of human development and natural protection information, which integrates administration, the economy, technology, and culture. In the practice of national agricultural regionalization protection, the theory of cultivated land use and protection is consolidated. The CLPP continues to maintain continuity, stability, and sustainability, and plays a supporting role in China’s socialist modernization. The value and importance of CLPP in this era are reflected in the practice of the new development stage, new development concepts, and new development patterns of cultivated land protection. The completion of the goals and tasks of cultivated land protection does not mean the end of the system, but that China will continue to implement the world’s most stringent cultivated land protection system. The evolution process of CLPP is the result of the game of multiple stakeholders, which shows significant path dependence characteristics. Therefore, how to use policy implementation to effectively improve the self-enthusiasm of stakeholders has become the key to the innovation of cultivated land protection system in the future. In particular, we should find a safety coefficient interval to balance the cultivated land protection and construction needs of CLPP, and coordinate the interest demands and bureaucratic structure of different subjects. Some pension policies, low interest loan policies, preferential taxes, and other policy compensation should be explored in the institutional framework of cultivated land protection. In addition, we should strengthen agricultural production technology, agricultural product marketing, and other supporting measures to improve the enthusiasm of agricultural managers.

- (3)

- CLPP should be based on the connotation of cultivated land and its protection objectives, and then implement adaptive governance for different forms of cultivated land use. Some factors such as the allocation of land use indicators and their marketization should also be fully considered to ensure the authority and applicability of the policy. Simultaneously, we should promote the legislation of cultivated land protection from the aspects of legal concept, control methods, compensation means, target responsibility, which will be beneficial to improve the systematization and integrity of the legal system related to cultivated land protection. Furthermore, the cultivated land protection system needs to cope with the transformation of cultivated land use brought about by climate change, smart agriculture, and food system transformation, and it must become more inclusive and sustainable in the process of ecological governance. The system can support the higher productivity levels of economic growth, such as sustainable intensification of cultivated land use. Scientific and technological innovation and technology integration play various roles in the implementation of cultivated land protection systems, which can create extensive efficiency. In addition, accurate assessment of human needs, seed quality, cultivated soil, and agricultural product trading will be the basis for effective protection of cultivated land.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gottero, E. Identifying vulnerable farmland: An index to capture high urbanisation risk areas. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 98, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorward, A.R. Agricultural labour productivity, food prices and sustainable development impacts and indicators. Food Policy 2013, 39, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Linner, H.; Messing, I. Agricultural land needs protection. Acta Agric. Scand. 2012, 62, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, R. Optimal farm management responses to emerging soil salinisation in a dryland catchment in eastern Australia. Land Degrad. Dev. 2015, 8, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Song, C.; Shen, S.; Gao, P.; Zhu, D. Spatial pattern of arable land-use intensity in china. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolow, A.D. Federal policy for preserving farmland: The farm and ranch lands protection program. Publius J. Fed. 2010, 40, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, P.C.; Gerber, J.S.; Engstrom, P.M.; Mueller, N.D.; Brauman, K.A.; Carlson, K.M.; Cassidy, E.S.; Johnston, M.; MacDonald, G.K.; Ray, D.K.; et al. Leverage points for improving global food security and the environment. Science 2014, 345, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zabala, A. Land and food security. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, M. Thirty years of farmland preservation in North America: Discourses and ideologies of a movement. J. Rural. Stud. 1998, 14, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L.R.; Hendrix, W.G.; Lohr, V.I.; Kaytes, J.B.; Sayler, R.D.; Swanson, M.E.; Elliot, W.J.; Reganold, J.P. Linking ecology and aesthetics in sustainable agricultural landscapes: Lessons from the Palouse region of Washington, USA. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 134, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnan, A. The financialization of agri-food in Canada and Australia: Corporate farmland and farm ownership in the grains and oilseed sector. J. Rural. Stud. 2015, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, L.; Powell, L.J.; Wittman, H. Landscapes of food production in agriburbia: Farmland protection and local food movements in British Columbia. J. Rural. Stud. 2015, 39, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, D.V.; Newman, L. The efficacy and politics of farmland preservation through land use regulation: Changes in southwest British Columbia’s Agricultural Land Reserve. Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangue, Y.D.; Melot, R.; Martin, P. Diversity of farmland management practices (FMP) and their nexus to environment: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 114059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsch, H.; Osterburg, B.; Roggendorf, W.; Laggner, B. Cross compliance and the protection of grassland–Illustrative analyses of land use transitions between permanent grassland and arable land in German regions. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiguchi, T. Japan’s Agricultural Policies after World War II: Agricultural Land Use Policies and Problems. In Social-Ecological Restoration in Paddy-Dominated Landscapes; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.H.; Lee, D.Y.; Jeong, D.K.; Kuppusamy, S.; Lee, Y.B.; Park, B.J.; Kim, J.H. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) concen-trations in the South Korean agricultural environment: A national survey. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 1841–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Huang, X.; Sloan, M.; Skitmore, M. Spatial-temporal evolution and classification of marginalization of cultivated land in the process of urbanization. Habitat Int. 2017, 61, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, B.; Zhang, X.; Bai, X.; Fu, B.; Chen, D. Four steps to food security for swelling cities. Nature 2019, 566, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qiao, L. Innovating system and policy of arable land conservation under the new-type urbanization in China. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 34, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.B. The Connotation and realization path of ecological governance of cultivated land protection in China. China Land Sci. 2020, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Zhang, X. Exploring environmental efficiency and total factor productivity of cultivated land use in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 726, 138434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, J. The differences of institutional performance of farmland protection in China. J. Public Manag. 2010, 7, 21–30+123. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.; Zhang, H. Performance evaluation on the policies of cultivated land protection in China from the perspective of quantity protection. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2010, 20, 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Liu, T. Improving the effectiveness of the protection of farmland in the new era of China. Res. Agric. Mod. 2018, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Li, C.; Mi, G.; Li, L.; Yuan, L.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, F. Maximizing root/rhizosphere efficiency to improve crop productivity and nutrient use efficiency in intensive agriculture of China. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Tan, M.; Kong, X.; Xu, Y.; Xu, E.; Shang, E. Research on the strategy for improving cultivated land quality in China. Strateg. Study CAE 2018, 20, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Shi, Y.; Chen, C.; Yu, M. Monitoring cropland transition and its impact on ecosystem services value in developed regions of China: A case study of Jiangsu province. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Qu, Y.; Sun, P.; Yu, W.; Peng, W. Green transition of cultivated land use in the Yellow River Basin: A perspective of green utilization efficiency evaluation. Land 2020, 9, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, C.; Song, W. Review of the evolution of cultivated land protection policies in the period following China’s reform and liberalization. Land Use Policy 2017, 67, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Huang, Y.; Choi, Y.; Shi, J. Evaluating the sustainable intensification of cultivated land use based on emergy analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 165, 120449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.G.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.J.; Chen, Y. Influence of government leaders’ localization on farmland conversion in Chinese cities: A “sense of place” perspective. Cities 2019, 90, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustaoglu, E.; Williams, B. Determinants of urban expansion and agricultural land conversion in 25 EU countries. Environ. Manag. 2017, 60, 717–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, X. Progress and prospect on farmland abandonment. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2016, 71, 370–389. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, X.; Niu, S.; Li, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhong, T. Present situation and trends in research on cultivated land intensive use in China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2015, 31, 212–224. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, L.; Liang, J. Optimal farmland conversion in China under double restraints of economic growth and resource protection. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Zhang, Z.; Carlson, K.M.; MacDonald, G.K.; Brauman, K.A.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Wu, W.; Zhao, X.; et al. Progress towards sustainable intensification in China challenged by land-use change. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Fang, B. Cultivated land protection system in China from 1949 to 2019: Historical evolution, realistic origin exploration and path optimization. China Land Sci. 2019, 33, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, S.; Lu, X.; Gu, G.; Zhou, X.; Peng, W. Sustainable intensification of cultivated land use and its influencing factors at the farming household scale: A case study of Shandong province, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Gong, Q.; Yang, W. The evolution of farmland protection policy and optimization path from 1978 to 2018. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2018, 12, 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, X.; Zang, Z.; Huang, X. The contradiction of cultivated land protection in the new era and its innovative countermeasures. China Land Sci. 2018, 32, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; He, Y.; Choi, Y.; Chen, Q.; Cheng, H. Warning of negative effects of land-use changes on ecological security based on GIS. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, B.; Han, J.; Lu, X.; Zhang, X.; Fan, X. Quantitative evaluation of China’s cultivated land protection policies based on the PMC-Index model. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Huang, X.; Chen, Y. Arable land conversion effects of basic farmland protection policy. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2012, 22, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Yan, J. Study on the decoupling of cultivated land occupation by construction from economic growth in China. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2007, 17, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, X.; Huang, X.; Chen, Z.; Tang, J.; Zhao, Y. Evaluation on the grain production performance of the cultivated land protection policy in China. Resour. Sci. 2010, 19, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, F.; Chen, J.; Chen, W. Theoretical and empirical study on the land conversion economic driving forces. J. Nat. Resour. 2005, 20, 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, T.; Mitchell, B.; Scott, S.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Lu, X. Growing centralization in China’s farmland protection policy in response to policy failure and related upward-extending unwillingness to protect farmland since 1978. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2017, 35, 1075–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, H.; Qi, Y. Construction land expansion and cultivated land protection in urbanizing China: Insights from national land surveys, 1996–2006. Habitat Int. 2015, 46, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Cai, Y. A new insight of cultivated land resource value. China Land Sci. 2003, 17, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Lu, Y. Preservation compensation accounting for farmland based on opportunity costs and Markov chains: A case study on Xuzhou City. Resour. Sci. 2015, 37, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Qu, F.; Jiang, H.; Jiang, D. Research on target of Chinese cultivated land protection based on excessive loss measurement and elimination. China Land Sci. 2008, 22, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Hao, J.; Liang, L. The value accounting of cultivated land resources in Huang-huai-hai Regio. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2009, 23, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, H.; Wang, K. Measurement and analysis of cultivated land protection externalities under different sample schemes. Resour. Sci. 2017, 39, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y. Rural households’ cognition of arable land value and protection willingness in economically developed areas of south China—A case study of Panyu district, Guangzhou. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2013, 34, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Wu, Z.; Ouyang, Z. Changes of cultivated land function in China since 1949. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2014, 69, 435–447. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Qiu, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, P. Impacts of difference among livelihood assets on the choice of economic compensation pattern for farmer households farmland protection in Chongqing city. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2012, 67, 504–515. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, B.; Wang, B. Study on value compensation for social responsibility of cultivated land based on the level of regional economic development. Geogr. Res. 2011, 30, 2247–2258. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.; Zhao, M.; Xu, T. Social benefits under land conservation policy: A choice experiment for non-market valuation. Issues Agric. Econ. 2017, 38, 32–40+1. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.; Shen, J. Farm land protection regulation in China based on the bargaining among multiple Stakeholders. Urban Dev. Stud. 2010, 17, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H. The behavior tendency and game relation about protectors of cultivated land resource security in China. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2009, 19, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H. Cultivated land protection: Game analysis of farmers, local government and central government. Reform Econ. Syst. 2011, 4, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. The changes in collective land rights system and agricultural performance—A review of research on agricultural land system during China’s forty years’ reform. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2019, 1, 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, G.; Wu, Q. On system obstruction of cultivated land protection in China: From the viewpoint of principal—Agent theory. China Land Sci. 2008, 22, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Li, X.; Song, W.; Kong, X.; Lu, X. Farmland transitions in China: An advocacy coalition approach. Land 2021, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.H.; Tian, Q.; Liu, Z.H.; Zhang, H.L. Virtual water trade of agricultural products: A new perspective to explore the Belt and Road. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 622–623, 988–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Kong, X.; Zhang, F.; Li, C.; Zheng, H. Analyzing the mechanism of economic compensation for farmland protection. China Land Sci. 2009, 23, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Song, G.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y. Study on compensation mechanism for cultivated land protection in northeast major grain producing areas based on the value of farmland development rights. China Land Sci. 2014, 28, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, B.; Qi, X.; Wang, Q. Theoretical framework and estimating the value balance between the occupation and reclamation of cultivated land within China. China Land Sci. 2013, 27, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, M.; Wang, K.; Guo, J. Research progress on ecological compensation mechanism of farmland protection. Res. Agric. Mod. 2019, 40, 357–365. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, L.M. Grounded theory. Medsurg. Nurs. 2013, 22, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, X. What influences the effectiveness of green logistics policies? A grounded theory analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 714, 136731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Original Data | Labeling | Conceptualization | Categorization |

|---|---|---|---|

| In November 2013, when President Xi Jinping visited Shandong province, he said, “we should add wings to science and technology in agriculture and lay emphasis on increasing production and efficiency, combining good seed and good law, combining agricultural machinery with agronomy, and coordinating production ecology. We should promote the integration of agricultural technology, mechanization of labor processes, production and operation informatization, legalization of safety and environmental protection, and speed up construction of the technical systems required by the development of safe agriculture with high yields, high quality, high efficiency, and ecology.” | p1 We should speed up the construction of technology systems to meet the requirements of high yield, high quality, high efficiency, ecological, and safe agricultural development. | P1 High yield, high quality, high efficiency, ecological, and safe | PP1 Technical systems |

| In December 2013, President Xi Jinping delivered a speech at the central rural work conference, “The fundamental guarantee for national food security is cultivated land, and it is the lifeblood of grain production.” Farmers can be non-agricultural, but cultivated land cannot be non-agricultural. If the cultivated land is not farmed, we will have no land to live on. | p2 Farmers can be non-agricultural, but cultivated land cannot be non-agricultural. | P2 Cultivated land cannot be non-agricultural. | PP2 Lifeblood |

| Circular on strengthening land management and stopping unauthorized occupation of cultivated land (the CPC Central Committee and the State Council,1986) suggested initiatives to “strengthen land management and resolutely stop the illegal occupation and abuse of cultivated land,” urgent circular on forbidding development zones and urban construction from occupying cultivated land and abandoning it (General Office of the State Council, 1992); circular on strengthening the management of various development zones (General Office of the State Council, 2003); urgent circular on suspending examination and approval of various development zones. The General Office of the State Council,2003, put forward “strictly control the loss of cultivated land”; circular on “no building houses in rural areas” (Ministry of Natural Resources, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Areas, 2020) | a6 Strengthen land management and resolutely stop the illegal occupation and abuse of cultivated land. | A6 Unauthorized occupation of cultivated land is banned | AA3 Management control (A6, A10, A21, A72, A73) |

| Circular on resolutely stopping the “non agriculturalization” of cultivated land The General Office of the State Council proposed that the permanent basic cultivated land that has been included in the core reserve of nature reserves should be included in the ecological conversion and be withdrawn in an orderly manner. | a82 Ecological returning of cultivated land | A82 Ecological returning of cultivated land | AA37 Balance and coordination |

| Dimension | Main Category | Primary Category | Connotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Situation | External environment | AA1 Consciousness awakening | Farmers have their own land; there is clear ownership of rural land property rights. |

| AA2 Clear concept | We should establish the basic national policy of cultivated land protection and pay attention to the protection and rational use of cultivated land. | ||

| Governance philosophy | PP3 Panda theory | Cultivated land is the most valuable resource in China, and as vital as the protection of the giant panda. | |

| Internal conditions | AA20 Production environment | It is necessary to classify soil organic matter and improve soil quality. | |

| AA22 Factor input | New agricultural inputs, such as new fertilizers, low toxicity and high efficiency pesticides, multi-functional agricultural machinery, and degradable agricultural film should be developed. | ||

| Structure | Stakeholders participate | AA34 Multiple stakeholders participate | Encourage government and social capital cooperation (PPP) mode, guide rural collective economic organizations, farmers, and new agricultural operators. |

| Motivation | Rice bowl theory | PP4 Keeps the rice bowl | Chinese people need to put their rice bowls in their own hands and hold their own food. |

| Red-line consciousness | PP5 Keep red line | Keep the red line of cultivated land protection firm. | |

| Bottom-line thinking | PP2 Lifeblood | Cultivated land is the lifeblood of food production. | |

| AA27 Bottom line thinking | We should stick to the four bottom lines: no change in the nature of public ownership of land, no breaching the red line of cultivated land, no reduction in grain production capacity, and no damage to farmers’ interests. | ||

| Action | Institutional rules | AA3 Management control | Using mandatory policy tools to strengthen land management, stop unauthorized occupation of cultivated land, stop “non-agricultural” cultivated land use. |

| AA4 Constraint incentive | Permanent basic cultivated land protection, spatial planning, three-line delineation. | ||

| AA6 Command control | Strictly control incremental and classified management, economical and intensive utilization of land use. | ||

| AA8 Technology | Topsoil stripping, national cultivated land reserve resources survey and evaluation, land and resources remote sensing monitoring “one map”, conservation tillage. | ||

| AA10 Supervision and inspection | Supervision and assessment, local government responsibility, and natural resources supervision. | ||

| AA11 Land use regulation | Land use regulation institution. | ||

| AA12 Law responsibility | The crime of destroying cultivated land should be established. | ||

| AA13 Index control | Cultivated land index, construction land index, agricultural land conversion index. | ||

| AA18 Economic measure | Land reclamation fees, cultivated land occupation tax | ||

| System construction | AA14 Broaden channels and control total amount | Quality improvement, combination of compensation and improvement, and improvement from drought to water; attract social capital and financial capital to participate in land consolidation and high standard cultivated land construction. | |

| AA16 Capacity reserve | A reserve of cultivated land quantity, paddy field, and production capacity should be established. | ||

| AA25 Land consolidation+ | Relying on the cultivated land protection mechanism driven by land consolidation technology innovation, a land consolidation mechanism dominated by the government, dominated by farmers and participated by the society will be formed. | ||

| Propaganda and guidance | AA5 Propaganda and guidance | Strengthen the propaganda of cultivated land protection. | |

| Supporting system | AA7 Balance of occupation and compensation | Land requisition and compensation. | |

| AA17 Joint responsibility system | Responsibility system of cultivated land protection, off-office auditing of cadres. | ||

| AA24 Economic compensation incentive | Compensation mechanism of cultivated land protection. | ||

| AA29 Ecological compensation | Ecological compensation system for forest, grassland, wetland, and soil and water conservation. | ||

| Space | Internal core | AA9 Quantity security | Cultivated land reserved. |

| AA23 Ecological elasticity | Ecosystem protection of cultivated land. | ||

| AA26 Quality tapping potential | High standard construction of basic cultivated land, prevention, control, and remediation of heavy metal contaminated cultivated land. | ||

| External concurrence | AA30 Rotation fallow | Rotation and fallow of cultivated land. | |

| AA32 Game competition | Construction occupation and agricultural structure adjustment. | ||

| AA37 Trade-off coordination | Ecological deterioration, disaster-damaged area, contaminated zone. | ||

| Composite space | AA35 Key protected areas | Grain production function zone and important agricultural product production protection zone. | |

| New strategy | AA19 Rural revitalization strategy | All the income from adjustment is used to consolidate the achievements of poverty alleviation and support rural revitalization. | |

| AA21 International trade adjustment | Make use of the international agricultural product market and agricultural resources to effectively adjust and supplement the domestic food supply. | ||

| AA28 Urban-rural integration | Break the institutional barriers that hinder the free flow and equal exchange of urban and rural elements. | ||

| Outcome | Capacity increase | AA15 Comprehensive production capacity | Steadily improve the comprehensive grain production capacity. |

| Peasants’ subject positions | AA31 Peasantry’s inclination | Respect peasantry’s inclination and implement them in a safe and orderly manner. | |

| AA33 Farmers’ interests | Farmers’ interests will not be damaged. | ||

| Sustainability | AA36 Continue increasing productivity | Comprehensively enhance the capacity of sustainable yield increase of cultivated land. | |

| Pattern optimization | AA38 Quantity-ecological- quality all in one | New pattern of special protection of permanent basic cultivated land with strong protection, intensive and efficient management, and strict supervision. | |

| Reform and innovation | AA39 Improve means | Improve the balance in the management of cultivated land occupation and compensation. | |

| Improve the system | AA40 Policy system | The permanent basic cultivated land management and control system, cultivated land protection system, and balance policy system need to be further improved. | |

| Ecological efficiency | PP1 Technical system | Accelerate the construction of the technology system to meet the requirements of high yield, high quality, high efficiency, ecological, and safe agricultural development. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niu, S.; Lyu, X.; Gu, G. What Is the Operation Logic of Cultivated Land Protection Policies in China? A Grounded Theory Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8887. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148887

Niu S, Lyu X, Gu G. What Is the Operation Logic of Cultivated Land Protection Policies in China? A Grounded Theory Analysis. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8887. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148887

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Shandong, Xiao Lyu, and Guozheng Gu. 2022. "What Is the Operation Logic of Cultivated Land Protection Policies in China? A Grounded Theory Analysis" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8887. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148887

APA StyleNiu, S., Lyu, X., & Gu, G. (2022). What Is the Operation Logic of Cultivated Land Protection Policies in China? A Grounded Theory Analysis. Sustainability, 14(14), 8887. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148887