1. Introduction

Since the introduction of cultural factors into finance, the idea that regional culture affects modern economic development and the governance behavior, strategic development, and operational strategies of micro firms has been supported by a large body of literature [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Although research has shown that culture can influence many aspects of the economy, the study of food culture on firm-level sustainable development has never been addressed. As a necessary and most frequent practice in our daily lives, food has always played an important role in the development of human society and human–earth interactions. Activities around food production have almost constructed the whole content of social sustainable development, which can be seen from the names of “hunting age” and “farming age” in the early human history. With the progress of civilization and the abundance of food, diet has been endowed with a rich cultural connotation. Eating behavior, including what to eat, how to eat, where to eat, when to eat, and with whom to eat, etc., has become an important part of human society. Food provides energy for people to maintain sustainable physiological activities, and forms unique food culture across regions. This culture, in the form of dietary attitudes and concepts etc., imprints regional features on people, becoming an indispensable part of individual identity [

5,

6,

7]. Therefore, can differences in food culture between regions explain the heterogeneity in firm-level sustainable development? In the context of sustainable development, the issue of “culture and sustainability” has attracted increasing attention [

1,

8,

9,

10].

This paper aimed to fill this research gap by investigating the impact of food culture—i.e., social norms involving dietary taste—on sustainable total factor productivity. As an important issue and strategic goal, sustainable development can promote the stable and healthy development of the national economy, which is a kind of development with equal opportunities and benefits, aiming to promote economic development and condition and to improve the quality of human life [

11]. Since 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought a huge negative impact on the global economy; in this context, sustainable development is crucial for the survival of firms. At the firm level, sustainable development has become more important for firms to go beyond short-term profitability, and towards economic, environmental, and social sustainability [

12]. At present, firms are striving to secure core competencies for maximizing firm value through sustainable growth [

13]. Therefore, we tried to explore how culture, an important informal institution, affects the sustainable development of firms.

We chose China as the research scenario because China is a country with a rich and diverse natural and geographical environment, which has resulted in social development trajectories and cultural traits with regional characteristics, making it an ideal research scenario for culture and sustainable development [

3]. The rich natural demographic features and ethnic customs have contributed to the very different styles of food culture in different regions of China, and China is internationally renowned for its unique food culture, which attracts many foreign travelers [

14]. One of the most important criteria for distinguishing factions is the taste of the food, of which “spicy” is often seen as the most important feature in distinguishing different cuisines. The regional spicy culture has played an important role in the development and evolution of food culture and has further marked social change and regional economic sustainable development with a distinctive food culture imprint [

5,

15]. With this in mind, we focused on how regional spicy culture, which represents food culture, influences business sustainability.

We focused on firm-level total factor productivity, which is a comprehensive indicator for evaluating the efficiency of firm development and is widely used in studies to assess the sustainable development of firms [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Our sample contains A-share listed firms in China. We constructed quantitative values of “spicy” through web crawler and text analysis, and we found that firms in regions in which spicy culture plays a more prominent role showed higher sustainable total factor productivity. Heterogeneity analysis showed that large firms, state-owned firms, and firms with export operations are more significantly influenced by regional spicy culture. The mechanism analysis showed that regional spicy culture can enhance the sustainable productivity by promoting proactive management behavior. The empirical results remained robust when we used alternative indicators, double-fixed effects, and replacement clustering robust standard errors. In addition, we addressed potential endogeneity and validated the causal relationship between regional spicy culture and sustainable productivity by using regional sunshine as an instrumental variable.

Our study may contribute to the emerging literature on cultural finance and sustainability, where current research perspectives on culture and sustainable finance focus on the implications of language, religion, and gambling [

2,

3,

21,

22,

23]. This paper used web crawlers and textual analysis to construct a regional spicy culture index and then investigated its impact on the sustainable total factor productivity. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to report a prevailing impact of food culture on corporate finance. Our unique contribution is demonstrating that food culture is a fundamental factor in explaining sustainable development. Moreover, our paper reinforces the micro foundations about the impact of culture on the firm-level sustainable total factor productivity. While current scholarship on total factor productivity pays more attention on the macroeconomic level, this paper examined the factors influencing sustainable productivity from a micro perspective based on culture, making it the first study to directly analyze the relationship between food culture and sustainable productivity. Again, this paper examined the underlying mechanism of regional spicy culture in affecting firms and empirically verified the positive governance of firms is an influencing channel, providing a plausible explanation for food culture. In addition, we extended and deepened the research related to informal institution and firm development. Our study explored how culture as an informal institution contributes to firm development in different regions from the perspective of food culture, which helps academics and practitioners analyze the informal institutional reasons behind firm development from a new perspective and provides a new perspective for the formulation of regional economic development policies. Finally, our article extended the research on health economics. Current health economics research focuses on the interaction between human health behavior and economics, and studies have confirmed the impact of health behavior on health and macroeconomics [

24,

25] as well as the impact of economic policies on human health [

26,

27]. We further prove the impact of food culture closely related to health on corporate finance.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the theoretical analysis and research hypotheses.

Section 3 introduces the data sources, processing, and main variables.

Section 4 reports empirical results, including the relationship between food culture and sustainable productivity, potential endogeneity issue, and robustness tests.

Section 5 discusses the mechanism analysis and heterogeneity analysis.

Section 6 reports the conclusion and contribution.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

According to institutional economics theory, on the one hand, firm behavior is constrained and limited by formal institutions; on the other hand, it is also influenced implicitly by informal institutions such as culture and religion [

28]. In traditional Chinese culture, which is characterized by Confucianism and a strong clan culture, formal institutions such as laws and regulations are less strongly held in the minds of the Chinese people than in Western countries. In contrast, informal institutions are more socially accepted and have a strong binding effect on corporate behavior, complementing formal institutions [

29]. Different regions have different cultural antecedents that are deeply rooted in individuals and groups, fundamentally altering individual preferences and attitudes as well as resulting in significant differences in behavioral decisions [

30]. Regional culture as an informal institution plays an important role in the cognitive and behavioral development of economic agents, and has been shown to homogeneously influence the management of local firms and further map onto the business management of firms [

1,

2,

3]. Thus, food culture as an explicit regional culture may play an extremely important role in corporate decisions.

Modern cuisines regard taste as an important criterion for differentiation, and regional differences in food culture are still evident, especially in terms of the “spicy” taste of the food, which has led to the formation of a distinctive regional spicy culture. Regional spicy cultures has played a significant role in the development and evolution of food culture and has further marked social change and regional economic development with a distinctive food culture imprint [

15,

31].

Regional spicy culture may significantly influence corporate behavior; on the one hand, regional spicy culture represents a positive, enthusiastic, proactive, and aggressive spirit [

31], which also tends to develop more reward-sensitive personality traits with a greater sense of accomplishment after achieving results [

32,

33,

34]. This implies that the mapping of regional spicy culture at the firm level may facilitate active management and increase the sense of achievement of executives who have been successful through active and proactive management, thus creating a virtuous circle that contributes to corporate sustainable development.

On the other hand, capsaicin can biologically enhance the body’s energy expenditure (for example, energy expenditure is significantly increased 10 kcal over 270 min on average after capsaicin diet) [

35,

36], resulting in the promotion of negative energy balance and fat oxidation (for example, respiratory quotient is significantly decreased 0.15 over 270 min on average after capsaicin consumption) [

35,

36], body temperature increase (for example, core body temperature is increased 0.02 °C on average after capsaicin consumption) [

35,

36], and peripheral and central fatigue reduction. The physiological mechanism of capsaicin is regulating tissue glycogen utilization and increasing plasma adrenaline concentration, enhancing the body’s excitement and positive emotion [

35,

36,

37]. Thus, in areas with a strong spicy culture, individuals themselves may be more likely to develop proactive and positive personality traits, which may further be reflected in positive management behaviors of corporate management and positive work attitudes of employees.

From a psychological perspective, the theory of benign self-mutilation can be used to explain the euphoria associated with spicy food. Benign self-mutilation refers to the individual’s feeling of negative experiences that the body or brain incorrectly interprets as threatening. The difference in cognitive and physical responses leads to pleasurable euphoria once the individual realizes that the real danger does not exist [

37,

38]. From the perspective of benign self-mutilation, the burning sensation caused by spicy food guides the body to falsely report danger and react defensively (e.g., sweating, tears). However, the individual realizes there is no danger, resulting in the burning, sweating, and tears caused by spicy food, which transform into a stimulating pleasure and develop more positive and aggressive emotions.

Overall, we infer that firms more affected by regional spicy culture are more likely to show proactive management, resulting in the promotion of sustainable productivity. Thus, we have:

Hypothesis 1. Regional spicy culture can enhance proactive management behavior to promote firm-level sustainable productivity.

3. Data and Variable Construction

3.1. Data Sources

We collected data from multiple sources. First, we obtained recipe data in August 2017 from the “Meishijie” website (

http://www.meishij.net/, accessed on 15 August 2017). “Meishijie” divides Chinese cuisines into 20 sub categories according to their origins, including “Xiang” cuisine, “Hui” cuisine, “Hubei” cuisine, and so on. The information of excipients and condiments in the menu of each dish (for example, the excipients and condiments used in Xiang cuisine “home cooked Steamed Chicken with Chili Sauce” include onions, ginger, garlic, sesame, peanuts, prickly ash, cooking wine, chicken soup, salt, chicken powder, sugar, balsamic vinegar, chili oil, etc.) was used as the main data source for extracting dietary tastes [

15]. More specifically, we obtained the recipe information of the 20 cuisines on “Meishijie” by web crawling. Considering that there is no unified measurement for the use of ingredients in recipes provided by “Meishijie”, we quantified the spicy taste of dishes by text analysis according to the frequency of auxiliary ingredients and seasonings in recipes. Specifically, we used text analysis to distinguish whether each ingredient of the dish can correspond to the spicy flavor. For example, “chili oil” was labeled as “spicy” while “salt” was not labeled as “spicy”. Through summarizing all the dishes of each cuisine and taking the average of spicy taste’s frequency of use in every dish, spicy taste quantitative index for each cuisine could be obtained.

The number of recipes and spicy value of 20 cuisines are shown in

Table 1. By comparing the spicy value in the 20 categories of cuisine, our results showed that the usage of the spicy taste is the most frequent in “Chuan” cuisine, followed by “Yungui” cuisine and “Xiang” cuisine. These results are basically in line with people’s general perception.

Next, we collected restaurant data from Amap (

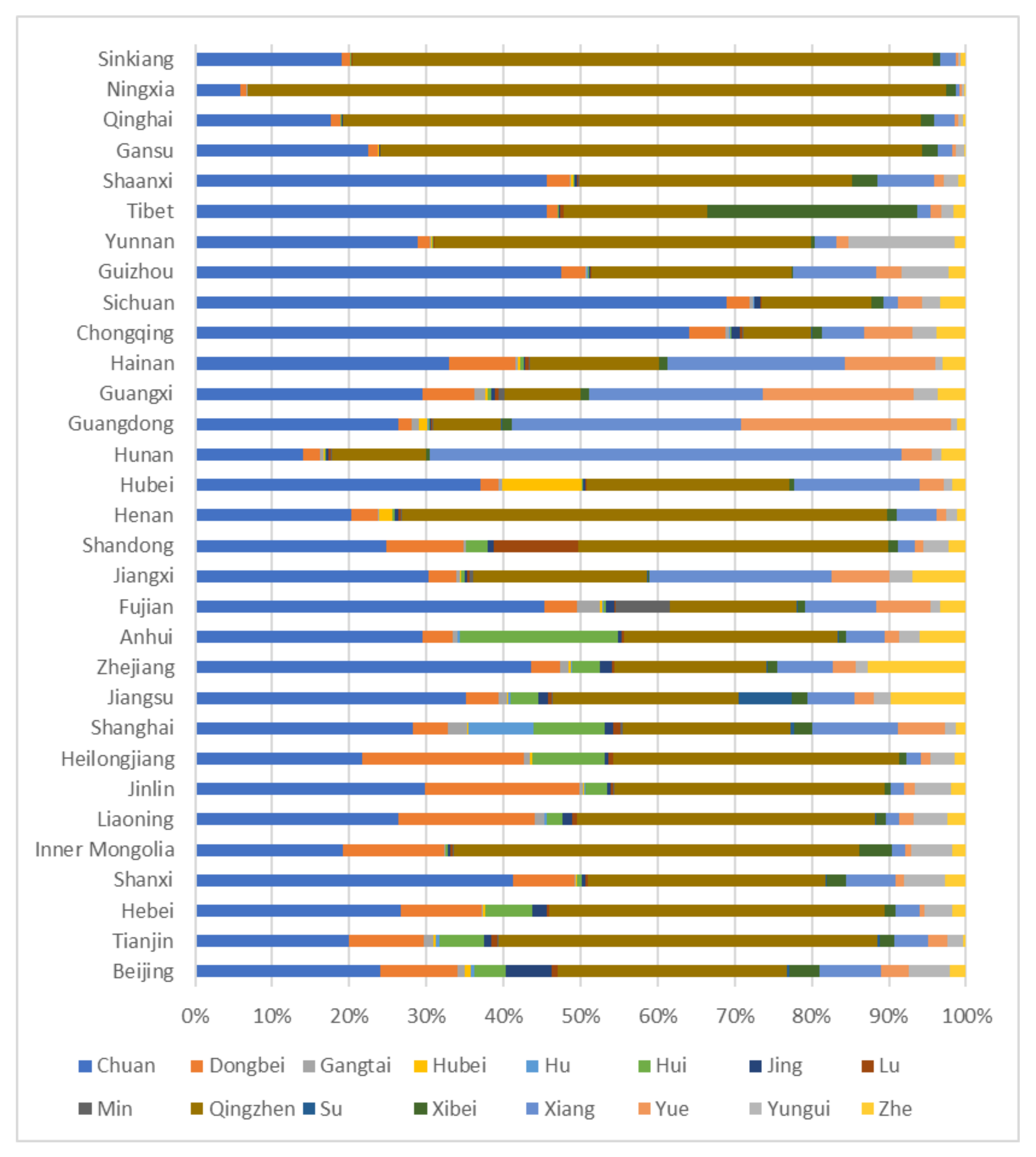

https://www.amap.com/, accessed on 15 August 2017), an electronic map website, in August 2017. We obtained data of more than 7 million restaurants in 31 provincial administrative regions in China, except Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan. Each piece of restaurant data may contain information of name, location, and cuisine. Such data were used to identify the proportion of each cuisine in each province. The 16 categories of cuisines used to classify restaurants all fell within the 20 categories of recipe data, and the data of restaurants corresponding to the 16 categories of cuisine common to both types of data were used to extract regional tastes. A total of 385,493 valid restaurants corresponding to the 16 categories of cuisines were distributed, as shown in

Figure 1, with Guangdong Province having the highest number of valid restaurants (63,411) and Chongqing the lowest (2442). The proportions of the restaurants of our 16 cuisines to the total valid restaurants in each provincial region were calculated, and the spicy taste indexes of each provincial region were calculated according to the spicy taste value of each cuisine. Taking the spicy index in Anhui Province as an example, we first calculated the proportion of “Hui” cuisine restaurants in Anhui Province. We then multiplied this proportion by the spicy value of “Hui” cuisine (

Table 1) as the contribution value of “Hui” cuisine to Anhui Province. We obtained the spicy index in Anhui Province by adding up the contribution value of 16 cuisines.

Based on the geographical origin of spicy culture, we collected data of sunshine hours from China Meteorological Administration for each provincial administrative region. We also obtained development-related indicators from China Statistical Yearbooks, such as GDP per capita, GDP growth, population growth, and consumption per capita.

Firm-level data were obtained from CSMAR and matched to regional information. The final examining period ranged from 2010 to 2019. We took A-share listed companies on Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchange as samples. We then excluded ST and PT companies, as well as the financial industry and real estate industry. The final sample included 10,180 firm-year observations with 2127 firms in 31 Chinese provincial regions.

3.2. Main Variables

Our dependent variable (TFP_lp) was firm-level sustainable total factor productivity calculated by the LP semi-parametric method [

18]. Alternate independent variable (TFP_op) was calculated based on the OP semi-parametric method [

17].

The main proxy variable of regional spicy culture (Spicy_PC) related to food culture in this paper comes from the spicy culture index calculated by using recipe tastes and restaurant data mentioned above.

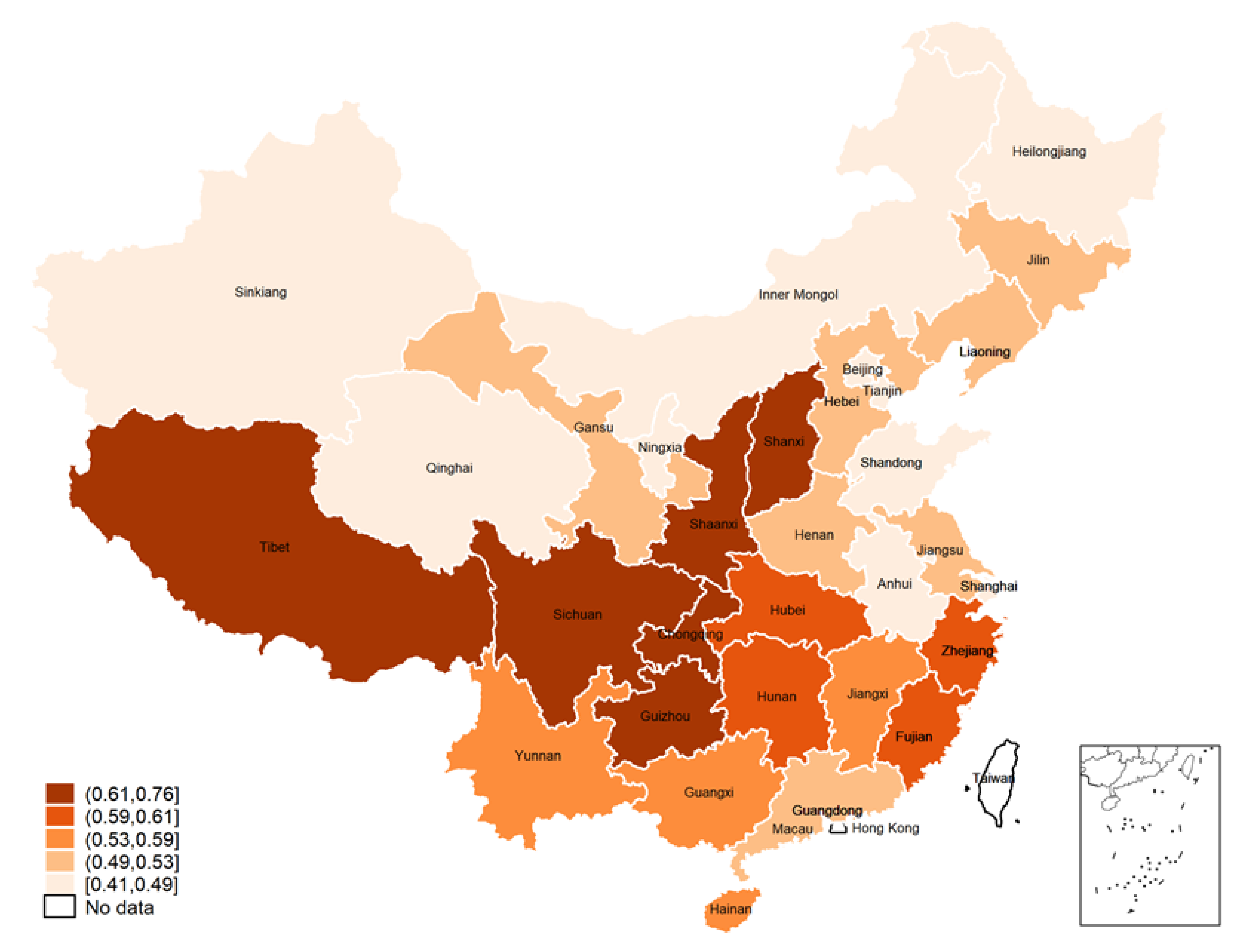

Figure 2 shows the regional spicy culture map based on Spicy_PC. Alternative variables for regional spicy culture were also constructed in this paper, aiming to capture the influence of spicy culture from the place of origin of the dish. Customers may have different perceptions of the same food business operating across locations [

39]. Specifically, this paper considered that in regions with lighter tastes, even restaurants with a higher number of heavier taste cuisines, the presence of spicy flavors may be reduced by the influence of the overall local culinary environment, i.e., the tastes of the cuisine of the region where the cuisine originated may dominate locally. Therefore, this paper used the spicy taste index of locally originated cuisines as a proxy variable for local spicy culture (Spicy_diet), and the proxy variable provides a reasonable robustness test for the main results.

Firm-level control variables include the logarithm of the firm size (Size), leverage (Lev), return on assets (ROA), book-to-market ratio (BM), analyst attention (Attention), annual stock return (RET), turnover ratio (Turnover), shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder (Top_1), shareholding ratio of top ten shareholders (Top_10), board size (Boardsize), proportion of independent directors (Indeboard), the logarithm of management compensation (Lncom), separation rate of management right and ownership (Separation), dual role for the board chairman (CO_CEO), and a dummy variable of state-owned enterprises (SOE).

Region-level control variables contain GDP per capita (GDP_per), the logarithm of consumption per capita (Consume_per), GDP growth rate (GDP_growth), and population growth (POP_Growth). We winsorized all continuous variables at the 1% level to avoid extreme values (our results are robust to this threshold).

Table 2 shows the summary statistical data of our sample, and lists the distribution of main variables. On average, the regional spicy culture index (Spicy_PC) was 0.541 and the standard deviation was 6.54%, indicating that there are significant differences among regions. In fact, regions in the 75th percentile (0.586) had a 19.35% higher spicy culture index than regions in the 25th percentile (0.491), and

Figure 2 shows a map of regional spicy culture in different provincial administrative regions in China. Similarly, the mean value of the spicy culture index (Spicy_diet) based on cuisine origin was 0.206 with a standard deviation of 0.217. The distribution of this variable suggests that the geographical distribution of spicy culture measured by cuisine origin is not uniform in China and provides side evidence that China can be a good scenario for studying regional spicy culture, with significant differences in the spicy culture index at the provincial level of the country.

In addition, the main dependent variable (TFP_lp) showed significant cross-sectional variation (the standard deviation was 0.998). The sustainable productivity located in the 75th percentile of the distribution (8.697) was 17.15 percent higher than that of firms located in the 25th percentile of the distribution (7.424), indicating significant differences in total factor productivity between firms.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Regression

We examine the relationship between regional spicy culture and sustainable total factor productivity in this section. We mainly rely on the following regression as a baseline model:

where,

is the total factor productivity calculated based on LP semi-parametric method of firm

located in Province

in year

, and

is the spicy culture index calculated by using recipe taste and restaurant data in province

p. Because the calculated spicy culture index is a provincial level datum that does not change over time, there is no need to lag.

are the control variables with a lag of one year. We also controlled the firm and year fixed effects to further solve the endogenous problem, and we used the double-clustering robust standard errors at the firm and year levels.

The results are shown in

Table 3. Column (1) provides the main regression results of all firms, and column (3) further controls the regional development indicators, including per-capita GDP (GDP_per), GDP growth (GDP_growth), population growth (Pop_growth), and logarithm of per-capita consumption (Consume_per). We can clearly see a positive correlation between regional spicy culture and sustainable productivity. For example, in column (4), a one-standard-deviation increase in spicy culture is associated with 9.53% standard deviation more of total factor productivity.

Columns (2) and (4) investigate the relationship between spicy culture and sustainable total factor productivity by using Spicy_diet, indicating our result does not change. In fact, by using the origin of spicy culture, the economic scale is even higher. For example, in column (4), a one-standard-deviation increase in spicy culture is associated with 11.38% greater standard deviation of total factor productivity. Overall, our results suggest regional spicy culture will improve the sustainable productivity.

4.2. Endogenous Treatment: Instrumental Variable Method

Although this paper explicitly controlled for many variables in the main regression, there are still possible problems of endogeneity and spurious correlations. To solve these issues, an instrumental variable (IV) approach based on geographical “shock” was used. It has been shown that social capital can be affected by geographical/climatic conditions [

40,

41]. Intake of spicy food is associated with removing dampness and strengthening the spleen, making it easier for dampness to escape, and the formation of a regional spicy culture is associated with at least two natural factors, one being the number of hours of sunshine and the other being air humidity and winter temperature [

32,

33,

34]. The findings suggest that low sunshine counts and wet and cold winters are the main environmental factors shaping regional spicy cultures and that differences in winter sunshine hours can often lead to differences in wet and cold winters across different regions [

42].

Therefore, this paper argues that sunshine hours, as an important geographical “shock”, can significantly affect the formation of spicy culture without directly affecting business activity. Specifically, our article used the annual sunshine hours in each province as an instrumental variable and uses the winter sunshine hours in each province as a robustness check, given that the weather in winter (astronomy divides winter into January, February, and December) is likely to be the coldest and wettest time of the year.

This paper expects sunshine hours as an instrumental variable unrelated to firm-level sustainable total factor productivity, as sunshine hours are purely a geographical “shock”. Therefore, the instrumental variable in this paper can be introduced as an exogenous natural geographical variation in the sustainable productivity. In other words, sunshine is a reasonable instrument because it satisfies both the inclusion and exclusion restrictions [

43].

Based on the instrumental variable of sunshine hours, this paper used the two-stage least squares method:

where,

is the instrumental variable of the first stage regression,

is the predicted value of spicy culture obtained by the first stage regression, and the other variables are as described above.

The results of IV regression are shown in

Table 4. First, this paper used regional annual sunshine hours (Sunshine) as the main instrumental variable, and reports the results of the first and second stages in columns (1) and (2) respectively. Our results showed less sunshine hours significantly strengthen spicy culture in the first stage, and in the second stage, instrumented spicy culture significantly promotes sustainable total factor productivity. We further conducted a series of examinations to check the effectiveness of IV regression. More specifically, our paper used Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistics to test whether IV (Sunshine) is related to the independent variable (Spicy_PC). As we can see from

Table 4, two F-tests all confirmed that Sunshine is not a weak instrumental variable.

In columns (3) to (4), we used the sunshine hours in winter (Sunshine_win) to test the robustness of IV regression. Specifically, total sunshine hours in January, February, and December each year were used to identify robustness. The results are similar to the above, and the F-tests showed that Sunshine_win is effective. Combined with the results of columns (1) and (2), our results support the causal relationship between regional spicy culture and sustainable total factor productivity.

We further applied our instrumental variables (Sunshine and Sunshine_win) to the alternative independent variable (Spicy_diet) in

Table 5. Our results are similar to the above and further confirmed the geographical origins of spicy culture.

Overall, the analysis in this section supports the causal explanation of the relationship between regional spicy culture and sustainable total factor productivity. This causal explanation can be applied not only to the main relationship between regional spicy culture and sustainable total factor productivity in this paper, but can also be extended to proxy variables for regional spicy culture. Taken together, these results from the previous section suggest that regional spicy culture may play an important role in influencing sustainable productivity.

4.3. Robustness Test: Substitution of Dependent Variable

We further calculated the total factor productivity (TFP_op) of China’s listed firms by using the OP semi-parametric method so as to replace the dependent variable TFP_lp as robustness test [

17]. We took the above two spicy culture indexes as the main proxy variables of regional spicy culture. In

Table 6, columns (1) and (2) control firm characteristics, while columns (3) and (4) further control regional characteristics. Across all these different specifications, this paper found that the relationship between regional spicy culture and sustainable total factor productivity remained very positive. Overall, these results suggested that there is a fairly general relationship between regional spicy culture and sustainable total factor productivity, and the main regression results in this paper are robust.

4.4. Robustness Test: Changing Clustering Mode

Previously, we used the robust standard errors of double clustering at the firm and year levels. To further verify the robustness of our findings, the regression results in this section were verified as robust to the use of double-clustering robust standard errors at the firm and year levels (

Table 7), province and year (

Table 8).

6. Conclusions and Contribution

6.1. Research Conclusions

This article examined the impact of food culture, represented primarily by regional spicy culture, on firm-level sustainable total factor productivity. To control for country-level effects, we used China as the research sample. As China is a country with significant regional differences in food culture, we used a web crawler approach to obtain data on the food taste index and restaurants as well as construct a regional spicy culture index using text analysis. We found that firms in regions with stronger spicy culture are generally more motivated to proactively manage their total factor productivity, and the results were significant even after controlling for firm-level and year-level fixed effects as well as using double-clustering robust standard errors at the firm and year levels. Our results were still robust when using proxies for region spicy culture and sustainable productivity as well as clustering with replacement standard errors.

As the formation of spicy culture is influenced by geographical shocks, this paper used annual sunshine hours and winter sunshine hours as instrumental variables to address potential endogeneity. Tests based on these instrumental variables show a causal relationship between regional spicy culture and sustainable productivity. We further verified that regional spicy culture guides a proactive management mechanism that contributes to sustainable productivity by influencing the firm’s equity incentive behavior and executive gender ratio, which is in line with the “proactive management hypothesis”. We also used R&D intensity and patent output as well as corporate leverage to rule out the alternative “active R&D hypothesis” and the “aggressive risk-taking hypothesis”. Furthermore, we demonstrated that spicy culture has a heterogeneous effect on firms of different sizes, natures of ownership, and export behavior.

Overall, the findings of this paper provide new evidence on how culture influences the sustainable development of firms in the real economy and therefore have important normative implications. To the best of our knowledge, this article is the first study to suggest that food culture influences corporate sustainable development, confirming the positive impact of food culture, which reflects sideways that culture can be the basis of the economy.

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Contribution

Our article can serve as a useful supplement to previous firm-level sustainable development studies, in which scholars focus on formal institutions such as corporate governance and regulations. We can also promote the transformation of the firm-level sustainable productivity research paradigm from formal institutions-driven to informal institutions-driven. Our major conclusion is that food culture plays an important role in affecting local firms, improving their sustainable productivity. Our research indicates that spicy culture plays a vital role in explaining corporate governance. These findings may make contributions to institutional theory by identifying the role of spicy culture and how it affects corporate behavior. Our research is also conducive to understanding the determinants of firm-level sustainable productivity. Because firm-level sustainable development has a material impact on the social sustainability, especially facing the increasing economic and social uncertainty under the COVID-19 background, firms need to achieve sustainable development. Our research is helpful for understanding the important role that food culture plays in influencing corporate proactive management behavior. This article would enable scholars to more explicitly and comprehensively comprehend the relationship between food culture and firm-level sustainable development, thus promoting the research in theory and practice.

Thus far, our study is the earliest research to confirm that food culture is the external driving force behind firms achieving their sustainable development with significant implications for firms, regulators, and market participants.

For firms, our results could guide them in regions more affected by spicy culture to engage in corporate proactive management behavior that benefit corporate sustainable development and restrain negative management behavior that can harm the interests of firms, as firms affected by regional culture show the homogeneous cultural characteristics. For regulators, our findings imply that firms in regions less exposed to spicy culture generally perform less well in terms of proactive management. It is suggested that government regulators should develop relative policies to encourage firms in these regions to adopt more proactive management strategies. Besides, our findings remind the government to promote the communication of food culture in regions and even across the country in guiding firms to achieve their sustainable development. For market participants, our research indicates that interaction of food culture can help firms to achieve better sustainable development. Based on these results, customers and suppliers of firms should consider the food cultural environment in which firms operate when planning to conduct business cooperation with firms. Similarly, investors and creditors should take advantage of information on food culture environment to evaluate the sustainable operation of firms when making investment or lending decisions.

Finally, it is a research trend that the influencing factors of firm-level sustainable development are transitioning from formal to informal institutional research. Our article starts this shift from the realm of food culture, an important factor of informal institutions, as a first attempt. In the future, we can conduct more in-depth studies of informal institutions from other perspectives of food culture, such as food behavior or food connotation and so on.