1. Introduction

Achieving and sustaining well-being among individuals in general, and young people in particular, in today’s economy necessitates financial awareness. Young individuals must acquire the necessary financial knowledge and skills to improve their ability to make important financial decisions [

1]. It has been observed that the contemporary young generation places less emphasis on saving habits and money management, negatively impacting their lives and making them far more reliant on their families and government financial support, in addition to increasing their debt burden [

2].

Societies with a high level of financial literacy tend to produce individuals who are more capable of making sound financial decisions [

3]. Financial literacy is defined as an individual’s ability to gather and process financial and economic information and use it to make sound financial decisions regarding financial planning, money accumulation, and debt management [

4]. Financial literacy also refers to the capacity to handle, read, analyse, and interact with personal financial situations in a way that has a positive impact on well-being [

5]. Financial literacy allows individuals to manage their money efficiently and clearly, make appropriate investment decisions, direct behaviour towards saving, and take advantage of new available financial products and services. Financially literate individuals can reduce risk and diversify their investments [

6]. Furthermore, those with better financial skills can plan their career path and retirement savings more effectively [

7,

8], whereas those with poor financial skills and knowledge may have to borrow more [

9]. The financial literacy report (2014) reviewed by [

10] reported that, globally, only about 33% of adults are financially literate, confirming the existence of a financial literacy gap between developing and developed countries [

11]. This report further indicates that of the 33% who are financially literate, 35% are men, and 30% are women.

For example, in the Arab world, as a developing region, financial literacy, despite playing an effective role in developing financial copying behaviour [

12], has been reported to be low compared to other parts of the world [

13]. Saudi Arabia, which is part of the Arab region, was also reported to be one of the poorest countries in terms of financial literacy, with 29% of women and 34% of men being financially literate [

14]. Despite significant changes and reforms in its economy, Saudi Arabia is still regarded as having a low level of financial awareness and literacy [

15]. Saudi Arabia is also reported to have a low level of saving behaviour among its citizens, particularly those under the age of 35, who account for approximately 37% of the total population [

15,

16]. This figure is primarily attributable to the lack of financial literacy among the Saudi populace [

17]. It has also been revealed that the majority of Saudi university students are financially illiterate [

18].

Furthermore, it is estimated that approximately 45% of Saudis do not save and that more than 80% have no investment plans. Furthermore, Saudis receive loans from banks at exorbitant interest rates; Saudi banks have reported having approximately USD

$100 billion in outstanding loans in the country, not including healthcare, education, and housing loans [

19,

20]. These findings indicate the existence of a financial literacy gap in Saudi Arabia, one which must be bridged through collaborative effort by various stakeholders in the country to ensure greater self-control and confidence among individuals [

21] as well as their financial inclusion [

22]. It is therefore assumed that it is critical to develop the necessary strategies for increasing individuals’ financial literacy and directing their behaviour towards saving and obtaining other financial products and services. As a result, the Saudi government is continuing to work on developing financial literacy by introducing financial education and other necessary educational programmes [

23]. Saudi Vision 2030, for example, is a comprehensive plan developed by the Saudi government. The plan seeks to implement comprehensive economic reforms and to increase the savings rate of Saudi households from 6% to 10% of their income. The plan also aims to provide individuals with greater financial independence by granting them mortgages, savings portfolios and retirement plans. The Saudi Vision 2030 also focuses on increasing the contribution of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to the GDP from 20% to 35% [

24,

25,

26,

27].

The development of financial literacy entails more than just financial education and other training and development programmes. It also focuses on specific forms of social support, such as parental and peer influence. Parents, for example, have a significant influence on their children’s behaviour because they are the source from which children learn their consumer behaviour, particularly at a young age [

28,

29]. Parents are also a source of financial knowledge and information [

30], which influences their children’s level of financial literacy from birth to adulthood [

29]. If parents want their children to live efficiently, they must teach them about financial issues [

31]. Peers, particularly students and especially college students, also influence each other [

32] with regard to financial literacy [

23]. More specifically, peers influence the ways in which–and the extent to which–monetary values are learned and financial valuations are made [

28]. Among college students, for instance, peer influence can lead to improved financial capabilities and saving behaviour [

23,

33].

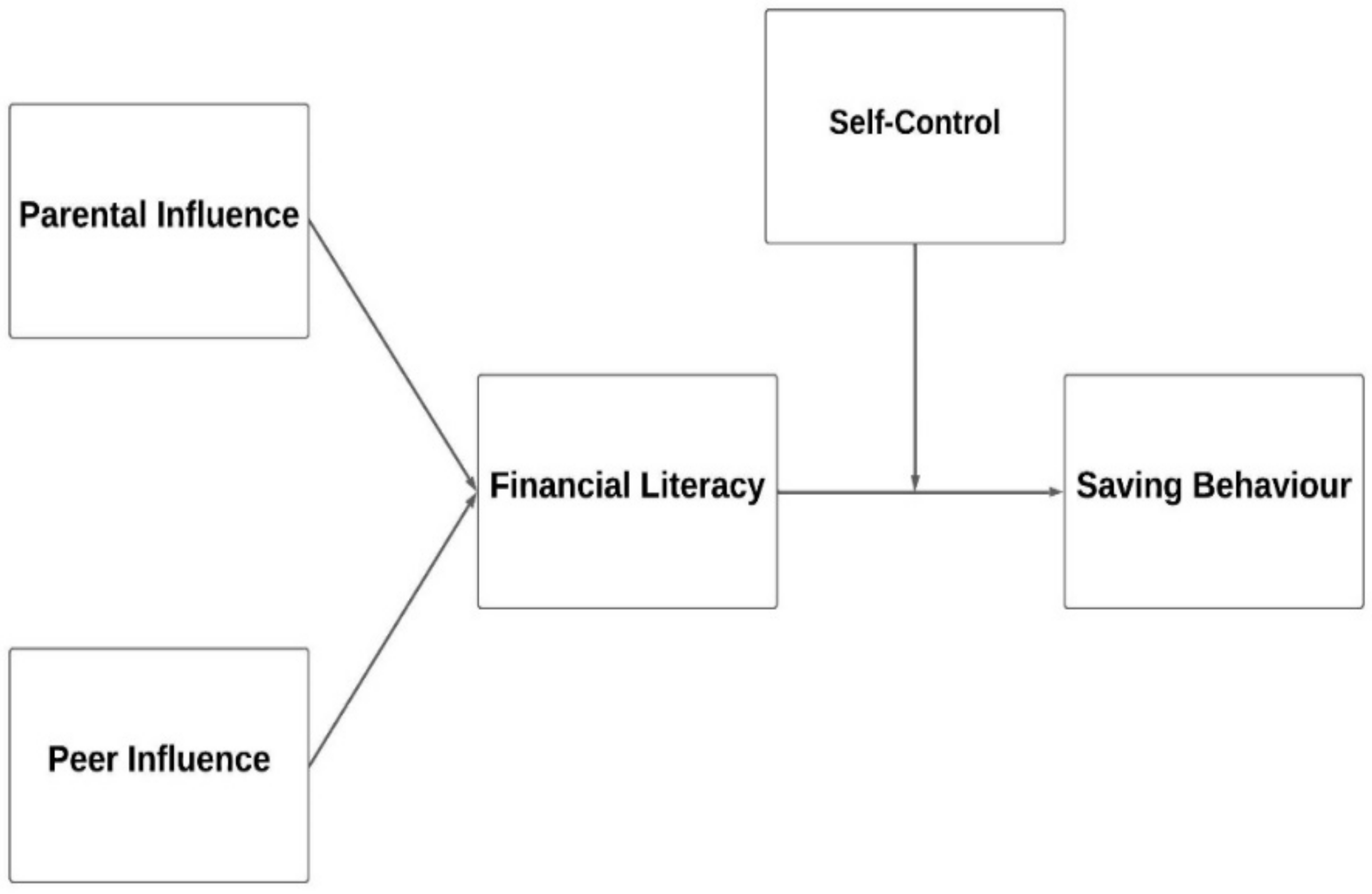

Put another way, when peers positively influence each other, they are all more likely to develop better savings and investment plans and make better use of their financial resources. When examining the impact on financial literacy and saving behaviour, it is important to consider not only the social influences mentioned previously but also individuals’ self-control, as it has been shown to play a moderating role between financial literacy and saving behaviour [

34,

35,

36,

37]. Self-control refers to a person’s ability to control their desires, opinions and behaviour in order to achieve specific goals, such as curbing bad purchasing behaviour and developing an appropriate retirement plan [

37,

38].

In light of this discussion, financial literacy is clearly a significant topic, especially given the paucity of literature on financial literacy and saving behaviour among young people worldwide [

39,

40] and particularly in Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, for a variety of reasons, there appears to be a low level of financial literacy and saving behaviour worldwide, especially among young people under the age of 35 in Saudi Arabia [

41]. Therefore, identifying the key factors influencing financial literacy and linking them to the saving behaviour of young people (students) in Saudi Arabia is a worthwhile research pursuit. Accordingly, this research attempts to fill the available research gap and respond to the call to investigate it due to its importance. Therefore, the study is based on a quantitative method and deductive approach using a 5 point Likert scale questionnaire to collect data from 270 young individuals (students) in Saudi Arabia belonging to an applied college affiliated with King Faisal University. The data was collected about social influence, financial literacy, self-control, and saving behaviour. The study’s findings reported the ability of social influence to impact financial literacy, on the one hand, and the ability of financial literacy to influence saving behaviour, on the other hand. The findings, however, showed no evidence of the ability of self-control in moderating the connection between financial literacy and saving behaviour. These findings will provide support and guidelines for policymakers and other stakeholders on encouraging and supporting financial literacy among people. Towards this end, this study sought to answer the following questions:

Do parental and peer influences affect the financial literacy level of Saudi young individuals?

Does financial literacy influence the saving behaviour of young individuals in Saudi Arabia?

Can financial literacy mediate the relationship between parents, peers and saving behaviour?

Can self-control moderate the relationship between financial literacy and saving behaviour?

Given that, we believe that this research provides theoretical and practical implications on how to sustain financially and have the ability to manage budget and life in general young individuals. This research is vital because it provides guidelines to policymakers and Saudi governments on promoting financial literacy, saving behaviour among young individuals, and the key factors determining financial literacy.

Accordingly, this paper is organised as follows: Following the introduction above, a literature review is presented and the development of the research hypotheses is discussed. Next, the research methodology is outlined and the results of the study are interpreted and discussed. Last, the implications of the research and its findings are presented, followed by some conclusions.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Participants and Procedures

The current study is quantitative and deductive. The deductive approach implies the presence of developed theories to support the background of the research. It requires researchers to develop hypotheses to be tested and accordingly confirm or reject the theories used. It is developed based on data and information gathered from primary and secondary sources. Whereas the secondary sources included various articles, books, and other materials, the primary data were gathered through an online questionnaire distributed to young individuals (students) from the applied college of King Faisal University. The study sample included 270 respondents (145 male and 125 female) who were either studying human resource management (HRM) or training to be a medical secretary. The study used convenience sampling for deciding the study’s sample due to its benefits and easiness of reaching respondents of the survey. It also saves time and effort, and cost too.

The study sample included young persons who had studied financial management during the course of their educational programme and who had also received some training in and attended workshops about the establishment of SMEs and entrepreneurship. Accordingly, these young people appeared to have some knowledge about financial issues, savings, and financial management, and they were selected accordingly. Furthermore, as the rate of financial literacy in Saudi Arabia is low, particularly among youth, examining the effect of the respondents’ surroundings, particularly peer and parental influence, on their level of financial literacy was considered especially compelling. It was also important to assess their level of self-control with respect to promoting saving behaviour.

Additionally, when compared to other students with bachelor’s and other degrees, students at applied colleges appear to experience difficulty finding jobs after graduation. As a result, instructing these students on how to rely on their social surroundings to become more financially literate, as well as assisting them in cultivating stronger self-control, may help them to learn to better manage their savings and potentially invest them in entrepreneurial firms.

The study used the 5-point Likert scale to collect the responses from the study respondents for its five concepts. The sample question for measuring financial literacy construct is: I have a better understanding of how to invest my money. In comparison, the sample question for measuring the respondents’ opinion of the parents’ influence is: My parents are a good example for me when it comes to money management. Furthermore, the sample questions for measuring peer influence, self-control, and saving behaviour included, respectively: I always discuss about money management issues (saving) with my friends; I always failed to control myself from spending money; to save, I often compare prices before I make a purchase.

Finally, concerning the questionnaire, we used a set of measures previously developed by different researchers in the English language; it was thus necessary to convert the questionnaire into Arabic and verify its quality prior to sending it to the respondents. Towards this end, the questionnaire was initially sent to 15 people to determine its quality. As no issues were found, the questionnaire was distributed to the study respondents and remained accessible online for approximately 1.5 months.

3.2. Demographic Information of the Respondents

A summary of the respondents’ demographic information is presented in

Table 1.

As shown in

Table 1, the majority of respondents (94%) were enrolled in the HRM programme, while only 6% were enrolled in the medical secretary programme.

3.3. Measures Used in the Study

The measures employed in the study along with their sources are listed in

Table 2 below.

The above references were used for developing the questionnaire measures. The measures were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘full agreement’ to ‘full disagreement’. Concerning the data analysis of the constructs, we utilised SmartPLS 3.1 when we performed the measurement model assessment. The items for respective constructs represented in the study provide the latent construct reliability and validity scores.

5. Discussion

Financial literacy is important for improving individuals’ financial well-being and saving behaviour, particularly among youth. As such, it is critical to identify the key factors influencing financial literacy. Accordingly, we examined the role of parents and peers in developing financial literacy among young people (students) in Saudi Arabia. We also investigated how greater financial literacy can lead to the development of saving behaviour moderated by individual self-control. The findings in these respects were intriguing. First, we determined the existence of a positive relationship between parental influence and young people’s financial literacy, which is logical given that it has been reported that those whose family possesses substantial financial knowledge typically inherit this knowledge from their parents. Parents are the primary source of instruction and encouragement for their children, from infancy to old age, concerning financial actions and behaviour, as supported by social learning theory. The current study’s first finding (Parental Influence → Financial Literacy) is consistent with results from previous empirical studies [

15,

21,

23,

29,

30].

Another finding of our study was the presence of a positive relationship between peer influence and young people’s financial literacy. This finding was also expected because people in general, and young people especially, inherit and develop their financial behaviour from their close friends given the substantial amount of time they spend together. Peers serve as role models for each other and, as a result, emulate each other’s behaviour [

52] and attitudes regarding, for example, monetary value and financial motivations [

28]. Peers also serve to motivate each other when it comes to personal savings [

51] and making financial decisions. The present study’s second finding (Peers Influence → Financial Literacy) is consistent with results from previous research [

23,

28,

51,

54,

55].

Our findings also revealed a positive and significant relationship between financial literacy and saving behaviour. This was an expected outcome as well because developing financial literacy encourages individuals to more effectively manage their personal finances, often culminating in the reinforcement and perpetuation of a culture of saving among young people. Individuals with greater financial literacy can create a better retirement plan, save more money, achieve financial well-being, and obtain a higher quality of life. This study’s third finding (Financial Literacy → Saving Behaviour) is consistent with findings from the existing literature [

58,

59,

60,

62,

75].

The fourth finding revealed that financial literacy has the ability to mediate the relationship between parental and peer influence and saving behaviour. This was also to be expected, as social influence is regarded as the primary source of developing financial literacy among young people, which ultimately leads to the encouragement of saving behaviour among them. This finding is supported by social learning theory, which states that people are influenced by their social surroundings and, as a result, develop specific behaviours (financial literacy leading to saving behaviour). As previously stated, numerous studies have confirmed the influence of peers and parents on the development of young people’s financial literacy [

23,

28,

29,

51,

54]. Additionally, once they gain financial knowledge, young people are more likely to develop saving habits [

59,

60,

62,

82].

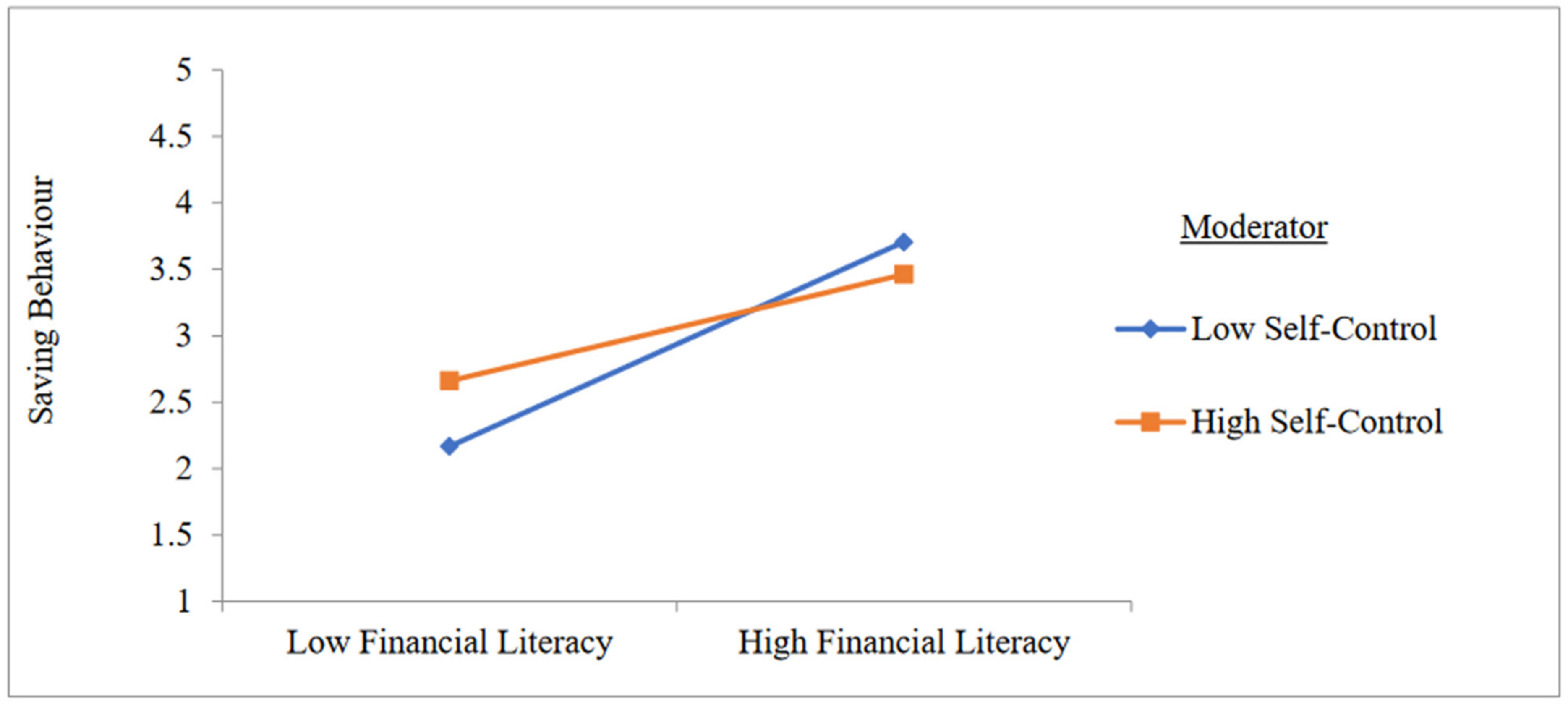

Finally, examining the moderation effect of self-control on the relationship between financial literacy and saving behaviour based on behavioural life cycle theory (BLCT) [

37] yielded an unexpected result. The study disclosed a significant negative moderation effect, indicating that the greater an individual’s self-control, the weaker the relationship between financial literacy and saving behaviour. This could be interpreted as a young person developing financial literacy from their social surroundings, such as parents and peers, which culminates in the capacity to save more. However, because they are young, they may lack maturity and control over their actions and decisions, making them feel less in control of their savings.

6. Implications

This study was one of the few to investigate the concept of financial literacy and its relationship with saving behaviour, social influence, and individuals’ self-control in the context of Saudi Arabia. The study thus adds to the existing literature and empirical findings on the role of social influence (peer and parental influence) in developing young people’s financial literacy, in turn encouraging their saving behaviour. The study also demonstrated the inability of self-control of young people to moderate the relationship between saving behaviour and financial literacy. This study provides guidelines and recommendations to various stakeholders in society on the importance of improving financial literacy among Saudi young people in order to help them develop healthier saving behaviour and achieve greater financial well-being.

Financial literacy and well-being among young people (students) can be developed by introducing effective financial education through, for instance, revising course curricula and syllabi for financial management subjects and other courses, as well as providing students with comprehensive financial training and consultation. These aims can be supported by inviting financially aware parents and peers to participate in the process of raising public awareness about financial literacy. The Saudi government, on the other hand, can help to develop financial literacy and saving behaviour by enacting laws and regulations that assist and encourage people in general, and young people in particular, to learn more about financial management and saving behaviour.

The Saudi government, in collaboration with the private sector, represented by commercial banks and other organisations, must work on developing the necessary financial products and services, financial training, and financial programmes for people in order to ensure better financial well-being and wiser financial decisions [

15,

22]. This study also emphasises the importance of developing self-control in young people in order to maximise the benefits of and learn how to best utilise their relative level of financial literacy. The study also highlights the importance of spreading awareness about the salience of financial literacy and how to benefit from it in Saudi Arabia (as financial literacy is estimated at 34% only in Saudi Arabia). Finally, the study provides insights for other researchers who are or plan to investigate how financial literacy influences young people to start SMEs as well as which factors can contribute to the sustainability of these enterprises.

7. Conclusions

The prevalence of poor financial literacy throughout the world, particularly in Saudi Arabia, underscores the need to identify the key factors influencing the development of financial literacy and saving behaviour as well as the extent to which self-control can strengthen or weaken the relationship between financial literacy and saving behaviour. As a result, given that the literature review revealed the scarcity of studies on financial literacy among young people in developing countries, we formulated the present study to investigate the state of financial literacy among Saudi youth. Our findings demonstrated the importance of both parental and peer influence in developing financial literacy as well as the salience of financial literacy in encouraging young people to save money. The study also found that financial literacy can mediate the relationship between peers, parents and the saving behaviour of Saudi youth. The study also found that self-control has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between financial literacy and saving behaviour. Therefore, financial literacy is critical in enabling individuals to develop saving habits and to effectively manage their personal finances.

In conclusion, even though researchers have attempted to explore one of the essential critical topics discussed globally, the study has some limitations. For example, the study targeted only one applied college affiliated with King Faisal University in Saudi Arabia with limited sample size. Furthermore, as the sample size is minimal, it is challenging for authors to generalize their findings in Saudi Arabia. Additionally, the study considered only two factors as antecedents for financial literacy where there might be some other factors which lead to the development of financial literacy among young individuals. Additionally, the study is only based on cross-sectional data. Accordingly, future studies may consider including more concepts and variables to predict financial literacy, such as financial education, national culture, etc. the study may also include more mediation and moderating variables to strengthen the relationships in the study model. Future studies may concentrate on examining the direct impact of self-control on saving behaviour and financial literacy and also indirectly investigate the influence of self-control through other constructs. Furthermore, future studies may consider increasing the sample size as much as possible to ensure better results and more convenient outcomes. There might be a possibility of comparing by taking a sample from more than one country and examining their differences. The study sample’s selection might also be collected with the help of a longitudinal data collection strategy rather than a cross-sectional one. Last, in future studies, researchers should attempt to use other sampling methods such as simple random sampling other than convenience sampling to ensure minimum bias in the study.