1. Introduction

The contemporary world is moving very fast towards the next stage of technological development. Currently, organizations operate in increasingly dynamic environments, characterized by significant and often unpredictable technological, political and economic changes. This, in consequence, involves the need to introduce continuous changes [

1,

2,

3]. The concept of sustainable development becomes the basis for social, economic, and technological changes. A radical change affects the ways of functioning of various areas of business operations, new technical and technological solutions, and management methods emerge, most of which are based on the increasingly applied digital technology, artificial intelligence, and innovative communication tools, creating a network in cyberspace [

4,

5,

6]. Digitization of social and economic processes has become a permanent part of our lives. The diverse contemporary instrumentation for gathering, analysing, storing, and exchanging information in the digital form undergoes rapid development and disseminates thanks to cost reduction. Communication networks closely link companies, people, governments. Online technologies enable the acceleration and optimization of financial, investment, production, commercial, logistic, educational, cultural processes. In such conditions, the possibility to be online has a decisive impact on the quality of our personal and professional lives, because it makes us feel deeply linked to the global community. This is a new wave in economic growth, as K. Schwab calls it, the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Industry 4.0) [

7,

8,

9].

The characteristic feature of the Fourth Industrial Revolution is a connection of technologies that eliminate the boundaries between the physical, digital and biological sphere [

7,

8,

10,

11]. Such technological transformations are accompanied by a redistribution of capital and production resources (including human resources), global rearrangements of powers in the world, thereby creating new development prospects and new threats for any already developed and operating national social and economic systems. In the conditions of the new reality, manufacturing processes will be performed using integrated and “communicated” devices, which mutually transfer data to one another on the current basis. This will also contribute to radical changes in the human’s role in the labour market. The employee’s scope of obligations will apply to design, management, and supervision over production processes [

12,

13]. These changes have already started to approach us in a very dynamic manner, and managers have to adopt new roles as knowledge and information management is increasingly becoming a key responsibility. A knowledge worker already determines success, and his or her fast response, skills, and talent become the driving force in the age of Industry 4.0 [

14,

15,

16,

17].

In the light of what has been said above, the principal research hypothesis of this study is as follows: The Fourth Industrial Revolution is an objective result of technological progress, which will radically change the traditional ways of doing business, and a consequence of this involves necessary transformations of the labour market towards the development of the talent management concept. Auxiliary hypotheses include:

the transformation of the labour market will change the role and functions of the man in production and business processes, which, in turn, will induce changes in human capital management methods.

employees with high qualifications and developed cognitive, social-behavioural and adaptation skills will experience a high demand on the labour market.

the talent management concept in the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution will be subjected to numerous attempted and actual transformations, which will contribute to its repeated development and make it one of the key human capital management concepts.

This study aims to demonstrate the need to change the talent management concept and trace the directions of this transformation in the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. In order to realize the goal that has been set, it is necessary to make scientific research which will give answers to the four fundamental questions:

How do we measure the lack of talent in the labour market?

What kind of relationships between technological progress and labour productivity can occur?

To what extent is technological potential utilized by workers?

How can technological development influence behaviour of workers and development of their skills (talents)?

In the paper, the authors proposed Economic Laziness Index (Talent Shortage Index) which was developed as an instrument responding to the questions raised. It is based on two basic indexes: labour productivity per person employed and labour productivity per hour worked. The indexes that have been proposed can be used as practical tools to control the effectiveness of talent management.

2. Materials and Methods

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (Industry 4.0) is a new wave of technological and social development, which refers to an organization of smart networks of machines and processes, knowledge resources and human capital to make the production and organizational systems more efficient and adapted to the rational utilization of all types of production resources. The basis of the Fourth Industrial Revolution became artificial intelligence created by human intelligence. The new concept relies on cyber-physical systems, implementing communication and coordination of cybernetic and physical elements by utilization of online technologies. Due to the ability to use the “digital trace”, cyber-physical systems integrate with production processes, resulting in a qualitative transformation of production chains and more efficient business and customer management [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

The main ideas of the Fourth Industrial Revolution are based on: the general implementation of information technologies-digitization and virtualization of all spheres of social and economic life; the use of Big Data in production and business processes; the dissemination of the Internet of Things and creation of machine-machine and machine-man communication; and the introduction of the Distributed Manufacturing and Circular Economy Concepts [

3,

7,

23,

24]. Generally, it can be stated that the Fourth Industrial Revolution shapes the future by the development of artificial intelligence, which reasonably solves complex problems, optimizing communication and production processes and in this way creates development opportunities for social and economic systems [

8]. The McKinsey & Company report demonstrates that in the nearest future half of all existing work-related operations will be automated and, due to advanced technologies, new industries, new specialities, new workplaces will appear.

However, the Fourth Industrial Revolution does not only offer new paths of socio-economic development, but also creates many social and economic problems. There is a high probability of shock effects in many areas of the economy, both in the sectoral context (traditional economy sectors will be liquidated completely or transformed), and in terms of the size of business structures. (From the beginning of 2020 we have been observing the phenomenon of eliminating micro, small and medium enterprises, and at the same time accelerated development of large corporate structures with an international/global range of operations.) In such conditions, structural transformations taking place in the economic system will be accompanied by the capital redistribution process (redistribution of assets between corporate structures) to close production chains and integrate them with Distributed Manufacturing and Smart Cities systems. As a result, not only investment flows and the sectoral structure of the world economy, but also the market economy system itself will change radically (monopolization of business relations will increase, and the market in its traditional forms will be only auxiliary). This, in turn, will change the balance of power in the world.

On the other hand, the monopolization of the economic system will induce a sudden growth in the level of social inequalities (including in the population of developed countries). The common introduction of artificial intelligence will further deepen this problem, as it will replace not only the man’s physical work but also intellectual work. Here, the problem is much deeper than in previous industrial revolutions when a reduction of low qualified employees was mitigated by them going to the zone of highly qualified labour. In the new technological order “knowledge workers (university professors, lawyers, doctors, accountants, financiers, economists, managers etc.) will have no place to migrate to due to the absence of any potential jobs” [

25]. This phenomenon, combined with the elimination of small and medium enterprises that have not adjusted to the new economic and technological realities, will create mass unemployment and a sudden social stratification. As a result, there will be a significant transformation in the labour market: the middle class as such will disappear; only highly qualified (talented) specialists will be sought on the labour market to operate the process of organizing, creating, and maintaining state-of-the-art technologies; and all the other potential employees will be sought only incidentally under transitional difficulties and for low wages. All this will create a higher demand for highly qualified employees who have developed cognitive, social-behavioural, and adaptive skills. In the future, talent, more than capital, will be the critical production factor. People with ideas and not routine-based employees will be the rarest and at the same time the most valuable business resource [

26,

27,

28]. Responsible human resource management using a redefined talent management concept will become key for the success of an organization in the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution [

16,

17,

29,

30].

Here, selected factors in the environment of the organizations will be presented that determine changes in the future organization’s functioning processes. First, these may include global migrations, a deficit of talented employees on the local and global scale as well as social and demographic change. In general, globalization consists of an increasing number of national economies being integrated beyond their borders. This process occurs through wider economic relations between organizations creating international business structures operating in different parts of the world. In this way, the worldwide economic system has been created where products, services, production factors, tangible, and intangible resources, including human resources, are being transferred without barriers. All this makes globalization itself, paradoxically, on the one hand, the cause of growth in talent mobility, and, on the other hand, a factor contributing to an uncontrolled flow of talents in the global economic system. Any possible closure of international boundaries increases access to talented people as well as the likelihood of finding talents for international corporations online. In such a case, any human resources that are unable to offer their high competences, skills, and professional experience to large corporations will remain on local labour markets. All this marks the beginning of a new wave of business globalization over the Internet and should become an impulse for implementing Industry 4.0 concepts. With this assumption, (physical) migration should be lower with the reason being that the majority of works will be performed remotely, without the need to move. This will allow talents to be found in various corners of the world. A market of talented employees will be created in cyberspace [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

In the present conditions, shortages in talents will become one of the most important challenges. The search for talents will lead to a transition of the contemporary labour market that should become more segregated and specifically selected. To this end, the action is necessary to move all the jobs, as far as possible, into the digital space. Only in this way the organization will have access to talents worldwide, at the same time reducing the costs of searching for talents. This problem will be a special challenge because the scarcity of talent will be a stimulus for the group of the most mobile people to grow (in the digital version) in the international arena. In connection with this fact, a justified change will be the phenomenon of the mass liquidation of existing jobs in their present form within the ongoing Fourth Industrial Revolution [

28,

36].

Another important problem in the analysis of the talent management concept conditions is the socio-demographic aspect. The assessment of social and demographic phenomena proves that this situation will also be an important barrier to human development. Concerning the statistical data concerning the demographic structure of the European Union member states, two phenomena can be observed. The first of them applies to the problem of an ageing society and the second one relates to a negative birth rate. According to long-term forecasts, it is estimated that in 2050 population growth in all the European Union member states will be negative. At the same time, Europeans’ life expectancies will increase and the share of persons in the post-working age will increase significantly (people over 65 years old) as compared to the working-age population [

37]. Analysing the recommended trends, we conclude that the war for talents will grow stronger. The shortage of talents will be the key problem of numerous countries [

28,

38].

Due to the mentioned factors and problems, business structures and all other organizations must immediately rethink the traditional human capital management models, including any talent management concepts utilized so far. Situation like this necessitates new approach to the processes of human resources management within the framework of creation integrated models of sustainable management of enterprise capital [

39,

40]. Any transformations must go towards active utilization of online technologies and complete digitization of the management processes. Such approach enables: the quick formation of an environment for searching for talents at a minimum cost of the talent management processes; the emergence of new spatial (in the geographic sense) opportunities to increase talent engagement in business processes; smart decision-making based on the utilization of big data technologies and analytics; the reduction in production costs and increased labour productivity; and the creation of a human capital management system in the organization (including talent management), strategically focused, which will intensify the organization’s sustainable development.

The research methodology adopted by the authors has been based on four pillars. First, the literature dedicated to the problem area and the prospects related, on the one hand, to the realization of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and, on the other hand, to the talent management concept. Second, statistical data regarding labour productivity per one person employed in the examined economic system (European Union-27 countries) and the productivity level per one hour worked. Quarterly statistical data for the study taken from the official site of the European Statistical Office. The period studied the 1stquarter of 2000–the 4thquarter of 2019. The data used have been also modified taking the 1stquarter of 2000 as the zero levels enable us to study the general trends of the indicators examined and the disproportions between them. Third, economic and mathematical modelling techniques have been used for the analysis of selected statistical indicators, places of convergence and divergence, places of growth, declining and side trend have been found. This is further described in detail while building the chronology of the changes taking place in the economic system of the European Union. Fourth, as a result of the studies performed, a method of calculating the original Economic Laziness An index (Talent Shortage Index) has been proposed, in other words, referring to the lack of talents in the economic system. As the method of calculation, a proposal has been made to look at the change of the data trend line inclination angle proving the size of the difference between A and B indexes, where A is the productivity level per one employed person in the economic system, while B is respectively the productivity level per one hour worked in this economic system (

Table 1).

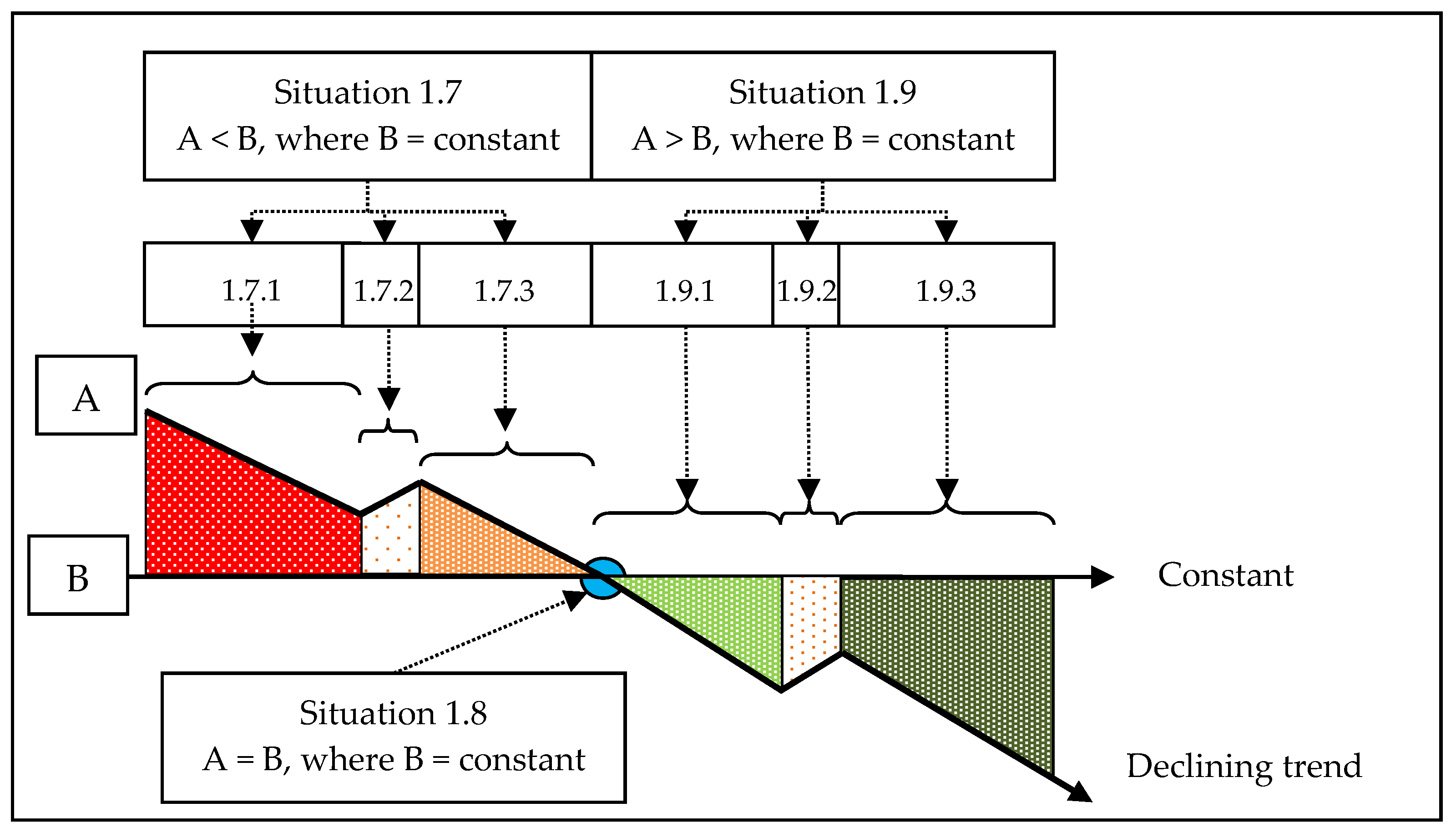

Using the original assumptions, we can generally expect the following situations.

Situation 1.0. The first situation is characterized by the stabilization of index B; let us assume at the level B

i−1. In such a situation, we can say that Band is in a side trend. On the other hand, index A data as compared to index B data can be moved at the same time in one of nine possible directions: side trend (situation 1.1., situation 1.2, and situation 1.3); growth trend (situation 1.4, situation 1.5, and situation 1.6); declining trend (situation 1.7, situation 1.8, and situation 1.9). The phenomenon data are schematically shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

In the case of one of such situations, we can start speaking about the probability of occurrence of an economic crisis. This is related to the fact that the location of index B (productivity per one hour worked) at a specified level proves no implementation of technologies and innovation to the production process. In this case, we can also speak about possible technological changes in the near future in connection with the fact that the present technologies do not offer any opportunities for increasing work productivity anymore or simply the employees, due to the lack of talent, are not capable of using them effectively. However, it is also worth drawing attention to the location of index A relative to index B.

Therefore, situation 1.1 proves that, when approaching this economic state, employee productivity was higher than productivity per one hour. Hence, productivity growth per one employee before entering this economic state was higher than productivity growth per one hour worked. This proves, on the one hand, the commitment of people, their diligence, and an increased number of man-hours per one employee. On the other hand, there is the dilemma: “The increased quantity of man-hours does not increase work productivity per one hour worked anymore”. On the other hand, the occurrence of situation 1.2 proves not only the possibility of an economic crisis but also the lack of talents in the economic system. This is related to the fact that index A is situated below index B, which may happen if the employees, at the moment of entering this economic state, worked less productively than allowed by the currently applied technology. Hence, employed people are not able to keep up with the existing technologies. This allows us to formulate another dilemma: “The lack of talents in the economic system creates an incomplete utilization of the technological potential of the economy examined as well as proves a declining involvement in production processes, which, as a consequence, leads to a reduced level of diligence and productivity among the employees”. From such a point of view, situation 1.3 is characterized by the fact that, at the moment of entering this economic state, the level of productivity of one employee in the economic system equalled the productivity level per one hour worked in this economic system. Hence, initially, we can state that the employees utilize the technological capabilities currently used in the economic system, and any further growth in productivity among the employees is dependent at the same time upon the degree of technology utilization.

However, one issue is that none of these three situations discussed above is favourable for the economic system and at the same time proves the absence of talents in the examined economic system. Why does it happen? Contrary to appearances, situation 1.1 proves that the employees are not able to use the potential of the present technologies effectively and to the full extent, which may be proof of the lack of talent, despite a high degree of commitment. Situation 1.2 from scratch is proof of laziness of the people employed, who do not keep up with technological progress and examine any introduced innovation only as a possibility to rest more and work less. Hence, we can observe that productivity per one hour worked is growing faster than per one employee employed in the economic system. In such a situation, we can speak not only about the lack of talent but also about economic laziness. Situation 1.3 proves the absence of talents indirectly. Simply put, due to the lack of talents in the economic system, no willing and outstanding employees have been found, who, with their history, could have forecast the possibility that such a situation can occur, and react in time by developing and/or implementing new technologies to social and economic processes.

Looking generally at the first situation, we may conclude that its occurrence in practice may result, for the economic system, in, on the one hand, the likelihood of cross-phenomena and, on the other hand, may be caused by the lack of talented people working in this system. In such a case, the simultaneous occurrence of a side trend of the two indicators examined is an unfavourable effect for the economic system.

Further classification of possible situations is based on the location of index A, being in a growth trend relative to index B being in a side trend (

Figure 2). Assuming that theoretically index A data can be below or above index B data, we can expand the original classification by further 7 situations.

In the case of situations, 1.4, 1.5, and 1.6 index B data are in a side trend, and thus the productivity level per one hour does not increase (or decrease). On the other hand, index A data change their value remaining in a growth trend, meaning that the particular peaks and valleys are located higher and higher, which suggests an increased productivity level among the employees when utilizing old technologies. Such a situation may occur only when there is no active implementation of new technologies in socio-economic processes. The location of index A data relative to index B will be of higher importance. In other words, whether index A data are located above or below index B data. Situations 1.4.1., 1.4.2, or 1.4.3 occur when A index values are below particular index B data. Situation 1.4.1 is characterized by the activation of economic processes and the desire of the people working in the given economic system to leave a crisis state. For this purpose, most likely, what is happening is an increased number of working hours, employee commitment and utilization of the gap that has emerged between people’s diligence and the degree of technological development. An attempt is being made to reduce laziness in society. After situation 1.4.1 there is a probability of occurrence of situation 1.4.2, during which we can expect a corrective wave in the growth trend, usually possible in the case of fatigue or failure to keep up with technology. We also believe that this correction, even though it is necessary, can result in a long-term declining trend, because index A data are already below index B data. In such a case, if the level is decreased below the previous minimum, this may increase the likelihood of long-term crisis phenomena in the economic system. On the one hand, this should force the authorities to pay greater attention to the economic processes in this situation, and, on the other hand, also increases the need for regaining and maintaining talented people in the economic system. Situation 1.4.3 may appear only when employees willing to develop, learn, develop their skills, acquire knowledge and search for possible technological solutions to improve work and increase productivity per one hour worked are still in the society.

The point of crossing the line built based on index A data from the area below line B upwards is a significant place characterizing adjustment of the present pool of employees to technological progress (existing in the given economic system). This situation is marked with the number 1.5. At this stage, we can try to talk about the reduction of the laziness index in the economic system. Here, it is also worth emphasizing the location of the present importance of index B in relation to its previous peaks and valleys.

Analysing situation number 1.6, we can expect that it may be very rare. This may be justified as follows: if we have hard-working and efficient people in the economic system (efficiency per working person is growing, but the level of the obtained efficiency per one hour worked does not increase), then it is very likely that there is the total absence of technological progress, which is contrary to the assumptions of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, or there is a state of exception in the economic system. Also, such a situation proves the absence of talents in the pool of people employed in a particular economic system. Situation 1.6.1 is characterized by an increased efficiency per one employee than per one hour he or she has worked. This proves the society’s awareness concerning the fact that a higher efficiency of each individual member of the society employed in the economic system will have in consequence a positive effect on the quality of life. However, considering the fact that index B remains in a side trend, this proves the lack of talents. Situation 1.6.2 is very similar to situation 1.4.2. The only difference is that situation 1.6.2 may be caused not only by fatigue but also by the so-called professional burnout. Situation 1.6.3 may appear only as a state of exception when the employees are forced, for any reason, to work more with no new technological solutions introduced to the production process. On the other hand, the long-term presence of index A above index B is not possible and will result in conflicts of interest in society. In the case of a situation when index A is in a declining trend, and index B remains in a side trend, the following options can be distinguished (

Figure 3).

In

Figure 3, index A data are in a declining trend, namely particular peaks and valleys are lower and lower. The marked situations are in fact a mirror reflection of

Figure 3. Hence, we can point out that in its essence situation 1.7 is characterized by a state of the economy when the society works more than the present level of technology development may allow, which is manifested in the impossibility to increase work productivity per one hour worked despite the society’s effort. As already mentioned earlier, such a situation would not last for a long time, and in the end, it will most likely result in a collapse of the economic system and a conflict in society. At this stage, important will be the behavioural response as well as the decisions made by corporations, governments and directly by large and small entrepreneurs, who act as employers. The effect of their activities will be visible during situation 1.7.2, and, in the case that they are not effective, situation 1.7.2 will change into situation 1.7.3 continuing the declining trend. The crucial point for the examined economic system is situation 1.8. This point can be defined as the zero point (productivity per one hour worked equals the productivity level of one employee in the given economic system at the present level of technological development).

In fact, situation 1.9.1 is the continuation of situation 1.7, when the employees worked over the standard and the effect of an attempt to mitigate the social conflict. On the other hand, situation 1.9.2 is similar to situation 1.7.2, when the role of employers, governments, corporations increases. The way they will act at this moment towards their employees, the society, the talents working in the given economic system will significantly affect the further development of the whole economic system and the level of social life. It should be pointed out that, on the one hand, well-rested staff (including talents) can start increasing their performance. On the other hand, the laziness variable already turns on at the given moment and further stimulation to increase effort may become a challenge for the management staff in the first place. Hence, the choice of the turning point, namely breaking situation 1.9.1 into situation 1.9.2, is a severe task and sensing this moment well can also contribute to the effect of the whole effort. At the end of the classification of possible changes taking place in the economic system, while index B is in a side trend, there is situation 1.9.3, the presence of which is actually a collapse of the economic system, resulting in a high likelihood of a long crisis of the examined economic system. The following situations can be additionally distinguished:

Situation 2.0. Index A data are in a side trend; index B data are in a growth or declining trend;

Situation 3.0. Index A data and index B data are simultaneously in a growth or declining trend-there is a convergence;

Situation 4.0. Index A data and index B data are simultaneously in trends of different direction (growing-declining, growing-side, declining-side or declining-growth)-in such a case, we can speak about a divergence between data of the indexes examined.

3. Results

The basic data considered to prepare the original business laziness index for EU-27 (real work performance indicator per one person employed in the examined economic system (A) and the work performance indicator per one hour worked (B)), after the modifications (an indication of the first quarter 2000 as the starting point) are presented in

Figure 4.

Analysing the basic data, we can formulate the following conclusions:

First, in the European Union’s economic system there is a continuous shortage of talents. This is because, from the beginning of the first quarter of 2000, the trend line for index A is below the trend line for index B. The inclination angle is respectively 0.208 (A) and 0.289 (B). When building the trend line for A

i-B

i, we can see a negative tendency, the equation of which is also presented in

Figure 4, (its inclination angle is negative and is 0.08 with a minus sign). Therefore, we can say that in the EU-27 economic system there is a tendency for business laziness and at the same time there is a continuous shortage of talents. Second, the statistical analysis of situation 1 and situation 2, when one of the indexes is in a side trend, namely when A

i = A

i−1 or B

i = B

i−1 occurred 15 times or 20% of the time, including a simultaneous side trend being present only once in the first quarter of 2008 (

Figure 5).

A side trend for the index describing the labour productivity level of one employee in the EU-27 economic system was present 8 times, and 8 times a side trend was present for the index of productivity per one hour worked. As we are approaching 2020, we can also notice how the frequency of the given phenomenon increases. In 2019, there was no quarter without problems with economic growth. The last two quarters are characterized by the lack of growth in productivity per one hour worked, which, in accordance with the authors’ assumptions, may result in a crisis in the economic system and proves the absence of innovative solutions being implemented for increased employee productivity or the impossibility to perform such actions.

As already mentioned above, from the point of view of the psychology of employee behaviour, when B

i = B

i−1, and at the same time Ai < A

i−1 and A

i < B

i and there is employee professional burn-out, a shortage of talents, and most likely no implementation of innovation in manufacturing processes, there is a noticeable absence of productivity increases per one hour worked in the examined economic system. Such a situation was present in 2007 Q3, 2013 Q1, 2014 Q2, 2017 Q1, 2019 Q2. In such a situation, the role of the management staff and the decisions they make increases (

Figure 6).

Adding data regarding convergence and divergence (

Figure 7) we can develop the whole chronology.

2000 Q2–2002 Q4-Growth convergence (Ai > Ai−1; Bi > Ai−1; Ai < Bi). At the same time, the productivity levels per one hour and per one employee are growing. In fact, the implementation of new solutions in technological processes is taking place.

2003 Q1-Declining convergence (Ai < Ai−1; Bi < Bi−1; Ai < Bi). Employee productivity in the economic system and productivity per one hour worked decrease simultaneously. The economic systemis thus incrisis. The roles of the decisions made by employers, management staff and the role of talents in the economic system increase. There is a need for immediate actions.

2003 Q2-Divergence (A going down, B growing) (Ai < Ai−1; Bi > Bi−1; Ai < Bi). After the decisions made at the previous stages, a continuation of the declining trend is visible for the index of productivity per one employee and, at the same time, productivity per one hour worked increases. This is the first situation of such type for the period examined, hence, the first serious change in employee behaviour is taking place-the level of business laziness is growing. This is justified by the fact that, with increases in productivity per one hour, employee productivity is not increased, but reduced. Therefore, in fact, the introduction of new technological solutions makes the employees read it as a possible reduction in workload (there is the phenomenon of laziness in society or professional burnout). Likely a conflict of interest in favour of employees.

2003 Q3–2007 Q2-Growth convergence (Ai > Ai−1; Bi > Bi−1; Ai < Bi). Long-term labour productivity growth with two conflicts of interest (2005 Q2 and 2006 Q3-general impact on the economic system-positive), when there is the phenomenon of divergence with simultaneous growth in employee productivity even at reduced productivity per one hour. In this situation, the winners are employers, hence, we can also state that employers dominate the labour market. There was no such phenomenon observed anymore. Probably due to the missing economic convenience of such a situation. Increased employees’ effort does not increase productivity per one hour worked, and we should expect higher wage costs (we are working more) at smaller labour productivity. This correlation may confirm the fact that increased productivity of one employee should not (cannot) be realized by increasing the amount of working time and only by the introduction of new technologies to the economic system. Confirming the authors’ hypothesis concerning the fact that economic growth is possible only through technological progress, namely the implementation of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. This is also confirmed by the fact that the majority of employees do not keep up with technological progress, which increases the need for comprehensive application of artificial intelligence and innovative solutions.

2007 Q3-Productivity per one employee remains unchanged (side trend) (Ai = Ai−1), Productivity per one hour is growing (Bi > Bi−1). The significance of such a situation is twofold. On the one hand, new solutions are introduced in the economic system (this is a positive phenomenon). On the other hand, any solutions introduced so far do not create productivity growth anymore among the persons employed in the economic system. Such a situation also creates a conflict of interest between employees and the management staff. In other words, manufacturing exactly the same amount as before, the employer should invest in the business. Therefore, investment in business does not bring the expected effect anymore, and this means that it is likely that such investment is unprofitable. This is a more peaceful phenomenon than the one which occurred in the second quarter of 2003 and was later repeated in the second quarter of 2012 (described below).

2007 Q4-Growth convergence (Ai > Ai−1; Bi > Bi−1; Ai < Bi). The behaviour of the management staff and the decisions made at the previous stage give a positive result for instance at the beginning in stopping any further reduction in productivity per one employee. The implemented solutions bring their effects in a short time.

2008 Q1-Simultaneous side trend-freezing of the economic system (Ai = Ai−1; Bi = Bi−1; Ai < Bi).A single presence of such a phenomenon for the period examined proves, on the one hand, its uniqueness, but on the other hand that the economic system has not experienced such a situation; yet it freezes the productivity level per one employee (proves that employees do not know what will happen next, and so, work the same as before). On the other hand, employers are also not sure of the future and thus do not invest in new solutions and technologies.

2008 Q2–2009 Q1-Declining convergence (Ai < Ai−1; Bi < Bi−1; Ai < Bi). After freezing the economic system there is the longest and, at the same time, the deepest correction wave on the previous growth trend. The productivity level per one employee and the productivity level per one hour worked wend down to the data from 2004. A very negative phenomenon, which caused serious consequences for the entire economy.

2009 Q2–2011 Q3-Growth convergence (Ai > Ai−1; Bi > Bi−1; Ai < Bi). Despite the growth in the productivity levels, the moment of going out of the 2008 crisis can be observed in the second half of the year 2010. Growth convergence proves employees’ awareness (including actual talents, which all the time there are shortages of) and the management staff concerning the need to stimulate personal, technological and social development.

2011 Q4-Declining convergence (Ai < Ai−1; Bi < Bi−1; Ai < Bi).

2012 Q1–2013Q1-No common human resource development concept.

2012 Q1-The productivity level per one employee decreases (Ai < Ai−1) at the constant productivity level per one hour worked (Bi = Bi−1).

2012 Q2-Divergence. The productivity level per one employee (Ai < Ai−1) continues to decrease with a simultaneous growth in productivity per one hour worked (Bi > Bi−1).

2012 Q3-Short term growth convergence. Most likely caused by the efficiency of solutions implemented at the previous stage. Still, such growth does not give a great effect per one employee anymore, which deteriorates and increases the difference between the pace of growth of the two indexes analysed. In other words, the implemented solutions do not produce any effect in a short time anymore. The advantage is still on the employees’ side; that is, the employer, while implementing technologies, does not expect any longer that employee productivity will grow at the same pace as productivity per one hour. There is a combat between two forces present in the examined economic system.

2012 Q4-The situation from the first quarter of 2012 is repeated.

2013 Q1-Productivity per one employee remains unchanged (side trend) (Ai = Ai−1), Productivity per one hour is growing (Bi > Bi−1). In such a situation, the role of the management staff and the decisions they make increases. The likelihood of crisis phenomena and social conflict increases. Deteriorated economic situation. It becomes harder and harder to increase the employee’s productivity level, and any technologies being implemented bring increasingly smaller effects.

2013 Q2–2017 Q4-Growth convergence, with the repetition of troubles in the second quarter of subsequent years.

2014 Q2-Index A remains unchanged, but the productivity level per one hour still increases, which, on the one hand, stops the situation from deteriorating further and, on the other hand, increases inefficiency of the economic system.

2015 Q2-At this moment, productivity per one hour remains unchanged, and the employees are forced to increase their productivity based on the existing technological solutions, the potential of which is not completely utilized by the continuous shortage of talents and the phenomena present in the global economy.

2016 Q2-Short term declining convergence.

2018 Q1–2019 Q4-No constant development of the examined economic system. The continuous change in the direction of the selected indicators can be observed. Productivity growth per one employee is not based on their increased productivity per one hour worked. Index B is in a side or declining trend almost all the time. The economy ceases to operate rationally and effectively. No cooperation and complex solutions are necessary to improve the situation and recover to a growing trend. On the other hand, the old economic system functioning for years indicates a shortage of talents, and low effectiveness of any implemented innovation as well as a poor motivation system in enterprises causing the formation of laziness in the society.

In the quality of employee productivity index and evaluation of their productivity per one hour worked, it has been proposed to use a calculation of the trend line inclination angle for eight periods, meaning that for the calculations we take A

i or B

i and 7 data preceding them (

Figure 8).

The calculation of the index data in a chain way enables us to evaluate changes in the situation. Therefore, a reduction in the indexes proves that the situation has deteriorated in the examined economic system and their growth, respectively, efforts to recover to the growing trend or a growth trend. Such an approach offers a more transparent vision of the processes taking place in the economic system and indicates weak spots in the talent management system to the management staff. The regression and variance analysis (

Table 2) between the data presented in

Figure 8 confirms the earlier formulated conclusions.

Therefore, we may state that the relationship between the received data is statistically significant, and the linear regression equation between the trend line inclination angle of the productivity level per one employee (index A as y) and productivity level per one hour worked (index B as x) looks as follows:

A proposal has been made to calculate the developed Economic Laziness Index (the index of the lack of talents in the economic system) also by an evaluation of the data trend line inclination angle proving the size of the difference between indexes A and B. The results of the calculations are presented in

Figure 9. Based on the received results of the conducted calculations, the following conclusions can be drawn: in the European Union’s economic system, there is a continuous shortage of talents on the labour market; from the first quarter of 2002 until the end of 2019, the values of the original Business Laziness Index decreased from the level −0.17676 to −5.69396, confirming the original research hypotheses; the present talent management concept needs a further transformation to adapt it to the current requirements on the labour market, which is the pursuit of neutralizing the differences between the pace of changes in the observed indexes A and B.

To control the effectiveness of talent management, a matrix system was proposed, based on calculating the author’s own Talent Shortage Index.

The matrix is divided into three main categories: the current value of the Talent Shortage Index, where three situations are possible: I

i > 0, I

i = 0 or I

i < 0; the current value of the Index in relation to its previous value, where further situations may arise: I

i > I

i−1, I

i = I

i−1 or I

i < I

i−1; evaluation of the degree of the talent shortage on a scale from 1 to 9 (

Table 3).

The “1” rating corresponds to a situation where the current value of the talent shortage index is above zero (Ii > 0) and higher than in the previously analysed period (Ii > Ii−1).

The “2” rating corresponds to a situation where the current value of the talent shortage index is positive (Ii > 0); however, it remains unchanged compared to the previous index value (Ii = Ii−1).

Ratings “1” and “2” show an increase in the labour productivity, intensive efforts to implement technological changes of the industrial revolution 4.0, increasing the efficiency and profitability of economic processes, development of human potential, high efficiency of the implementation of the Talent management concept.

The “3” rating, when the positive value of the current Index (Ii > 0) indicates a reduction in the labour productivity (Ii−1), shows a decrease in productivity and the problem of talent shortage. Therefore, it is necessary to find weak spots (gaps) in the implemented talent management concept and to develop this concept accordingly. The “4” rating is very close to situation “3” and indicates problems in the talent management system. Ratings “5” and “6” indicate a situation of stagnation and loss of opportunities for economic growth in the long term, showing significant gaps in the talent management, lack of optimal allocation of human resources, and lack of revolutionary development 4.0.Ratings “7”, “8”, “9” speak of a lack of efforts to adapt to requirements of revolution 4.0, with low development opportunities, show that the concept of talent management is in its initial phase; that is, human resources management is carried out according to current standards. The ratings correspond to a chronic talent shortage situation.