Assessing the Economic Contribution of Ocean-Based Activities Using the Pacific Coast of British Columbia as a Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Economic Contribution of Oceans

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Ocean Sectors

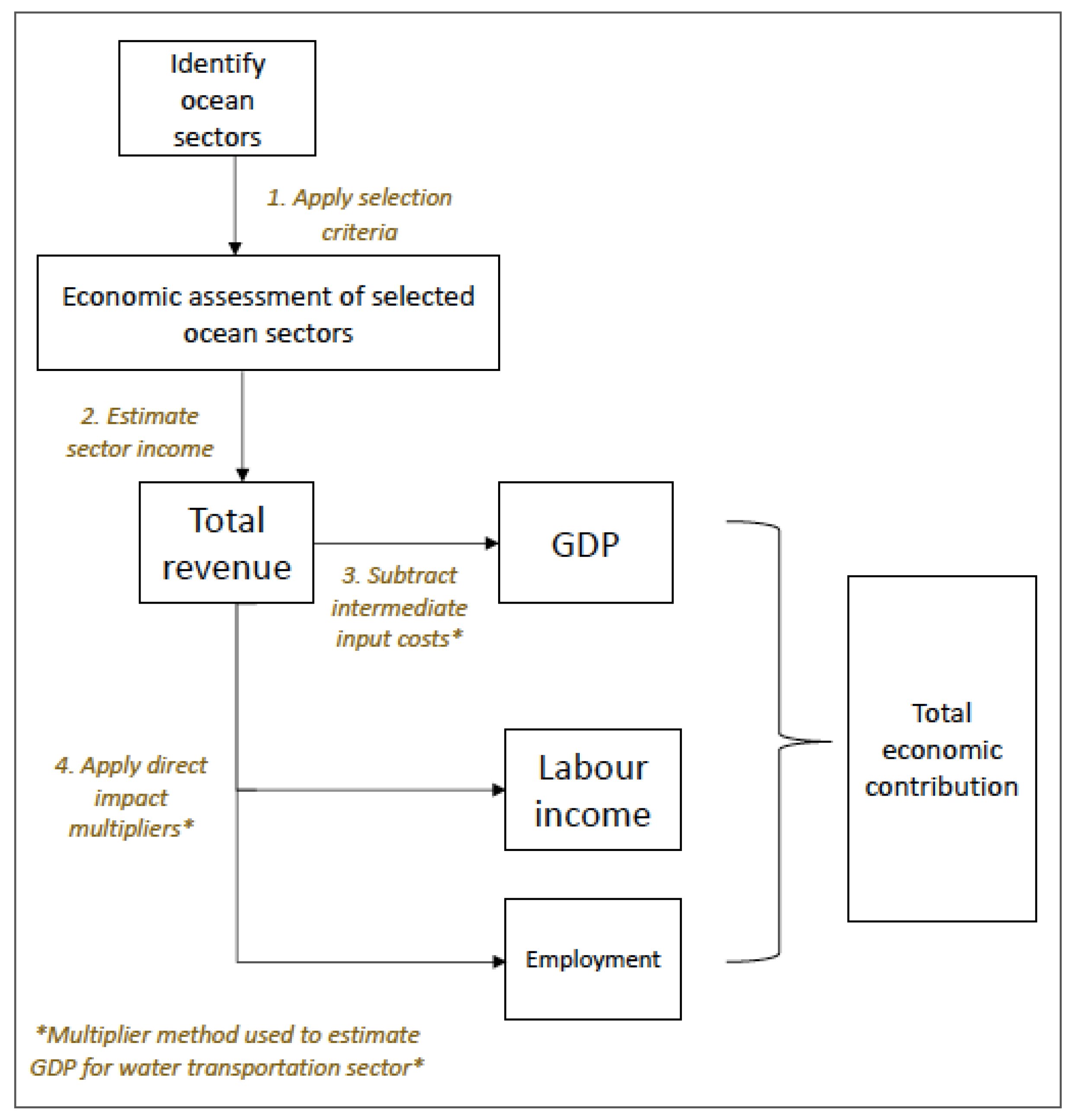

- Step 1: Defining Ocean sectors

- Step 2: Assessing economic impact on the economy

2.3. Living Sector

- Marine recreation and tourism—We accounted for popular ocean-based activities, based on participation rates from a survey of BC participants in outdoor recreation [31]. These included ocean-side activities (beaches, scenic viewing), kayaking, and whale watching. We summed up the direct spending of participants (locals and tourists) to estimate total revenue in the marine recreation and tourism sector. This similar methodology is used in other valuation studies of marine ecotourism [23,32]. We chose to use this method because it avoids the time-consuming and data-intensive task of accessing annual and monthly business administrative surveys for revenue and expenditure data of the more than 15 industries that are considered to be tourism-related [33]. In addition, due to confidentiality issues, revenue data may not always be publicly accessible, and these data may have to be obtained by conducting primary research [34].

- Recreational fishing—Total revenue was estimated by multiplying total recreational catch by the average angler expenditure per tonne of fish catch. Total recreational fish catch was extracted from the Sea Around Us database. Recreational catch surveys that monitor saltwater/tidal recreational fishing provide data on angler expenditures in terms of the number of fish caught. To convert this unit into tonnes of fish, we obtained length–weight conversions from Fishbase (https://www.fishbase.se/search.php) for the top 3 species caught by BC saltwater anglers, which were chinook, sockeye, and coho salmon [35]. The length–weight conversion was done using minimum length requirement measurements for the three species. We then converted the units of fish caught to tonnes of fish using the weighted average weight of the three top species, where the weighting was determined by the relative proportion of the three species in total reconstructed recreational catch from the Sea Around Us database. We divided total tonnage by total angler expenditure [35] to obtain average angler expenditure per tonne of fish catch.

- Wild fisheries—Total revenue was the landed value of total catch, which was calculated as fish catch multiplied by ex-vessel fish price for each taxa in the catch. Ex-vessel fish prices and total catch were extracted from the Sea Around Us database, where fish catch included reported and unreported landings and discards by Canadian industrial and artisanal boats fishing in the Canadian Pacific and United States Alaskan waters.

- Seafood processing and packaging—Total revenue in seafood processing and packaging was estimated by adding a processing margin to the total landed value of BC’s wild fisheries (described above). The processing margin was obtained by taking the averaged difference between wholesale value and landed value of wild caught BC seafood production from 2014 to 2016 [36], which is the added value from processing to prepare fish for the market [37].

2.4. Nonliving Sector

- 1.

- Cruise lines—The revenue generated from cruise tourism was estimated using the same approach as that for the marine recreation and tourism sector. Here, we summed up the spending by cruise vessels, and cruise line passengers and crew.

- 2.

- Marine transportation—Statistics Canada’s classifies this sector as establishments that are engaged primarily in the transportation of passengers and goods (e.g., ferries), as well as support services such as cargo handling, piloting, and harbour and port operation. Ancillary services such as maritime law and shipping supplies/equipment were also included as part of the ocean transport sector in the [29] economic impact study. Here, we consider marine transport to consist of three subsectors—freight and passenger transport, marine shipping, and support services.

- (i)

- Marine shipping—The activities in this subsector are typically classified as ‘support services’ for water transportation by Statistics Canada and include port and harbour operations, marine cargo handling, and navigation services to shipping. Economic impact arising from the marine shipping sector was calculated using employment as the base reference point rather than revenue, following the approach used in an economic impact assessment of the Port of Vancouver [38]. The InterVISTAS study [38] provided 2016 employment data, collected from surveys, for the Port of Vancouver. Employment data reported the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) jobs in five broad classes of port operations, i.e., maritime cargo; cruise; construction, vehicle, building and repair; non-marine-related services; and other marine-related services. We included maritime cargo and other marine-related services under the economic impact from marine shipping, while port operations related to cruise liners were attributed to the cruise sector in this study. The calculation of FTE jobs from 2000 to 2015 was based on one anchor point in 2015/2016 for which data was available. The total number of FTE jobs in 2016 in maritime cargo and other marine-related services was divided by total tonnage of cargo that moved through the port of Vancouver (138 million tonnes in 2015) to provide a job-to-tonnage ratio. This ratio was then multiplied by the volume of cargo handled by the Port of Vancouver in the years 2000–2015 to derive total FTE jobs in each of those years. Total cargo tonnage at the Port of Vancouver was raised by 30% to account for cargo volume handled at other BC ports. This percentage was based on data [39] that indicated the Port of Vancouver handled on average about 70% of total cargo tonnage that passed through the Pacific region from 2002 to 2011. Values for total revenue, GDP, and wages were then generated from the number of FTE jobs by applying input–output multipliers.

- (ii)

- Freight and passenger transport—We used BC Ferries revenue to represent this subsector’s economic output. Ref. [40] found that BC Ferries generated revenues of $365 million in 2000, which we used as an anchor point. This value was then extrapolated to 2015 using the Consumer Price Index (https://data.worldbank.org). Other industries that are typically included in this subsector are marine towing, ship chartering, and shipping [40]. Ship chartering is omitted from this study because the industry is not well developed in Canada [40]. Marine towing and the handling of cargo in the shipping industry are captured in the marine shipping subsector of this study.

- (iii)

- Support services—This subsector was only given cursory treatment in this study due to limited data and its comparatively low contribution to overall marine transport economic impact relative to the other two sub-sectors. We accounted for marine support services by taking 25% of revenue from the annual output statistics for the water transportation industry (BS48300) released by Statistics Canada. The proportion was based on a breakdown of gross output from BC’s ocean transport sector 2002–2005 [29], in which ‘other services’, covering shipping equipment and supplies, shipping agents, maritime law and other related businesses, averaged 25% of total output from 2002 to 2005.

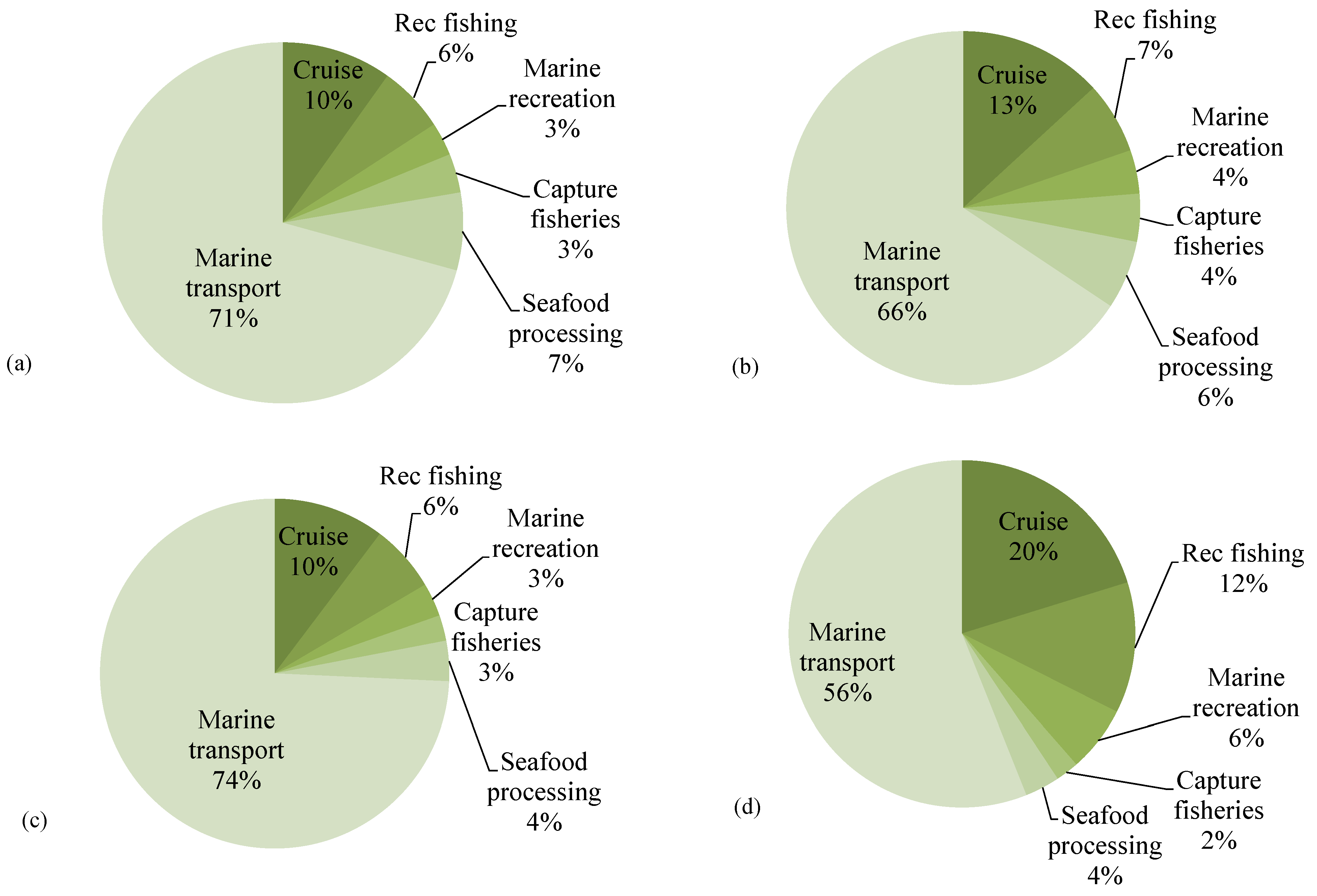

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Data and Other Factors That Influence Results

4.2. Limitations of Assessed Ocean Economic Contribution

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sather, C. The Bajau Laut: Adaptation, History, and Fate in a Maritime Fishing Society of South-Eastern Sabah; Oxford University Press: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; New York, NY, USA, 1997; 359p. [Google Scholar]

- Erlandson, J.M.; Fitzpatrick, S.M. Oceans, Islands, and Coasts: Current Perspectives on the Role of the Sea in Human Prehistory. J. Isl. Coast. Archaeol. 2006, 1, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Rodrigues, J.; Conides, A.; Rivero Rodriguez, S.; Raicevich, S.; Pita, P.; Kleisner, K.; Pita, C.; Lopes, P.; Alonso Roldán, V.; Ramos, S.; et al. Marine and Coastal Cultural Ecosystem Services: Knowledge gaps and research priorities. One Ecosyst. 2017, 2, e12290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.R.; d’Arge, R.; de Groot, S.; Farber, M.; Grasso, B.; Hannon, S.; Naeem, K.; Limburg, J.; Paruelo, R.V.; O’Neill, R.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, M. Sound Investment: Measuring the Return on Howe Sound’s Ecosystem Assets; David Suzuki Foundation: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2015; p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Worm, B.; Barbier, E.B.; Beaumont, N.; Duffy, J.E.; Folke, C.; Halpern, B.S.; Jackson, J.B.C.; Lotze, H.K.; Micheli, F.; Palumbi, S.R.; et al. Impacts of Biodiversity Loss on Ocean Ecosystem Services. Science 2006, 314, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eriksen, M.; Lebreton, L.C.M.; Carson, H.S.; Thiel, M.; Moore, C.J.; Borerro, J.C.; Galgani, F.; Ryan, P.G.; Reisser, J. Plastic Pollution in the World’s Oceans: More than 5 Trillion Plastic Pieces Weighing over 250,000 Tons Afloat at Sea. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allison, E.H.; Bassett, H.R. Climate change in the oceans: Human impacts and responses. Science 2015, 350, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment and Climate Change Canada Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators: Canada’s Conserved Areas. 2018. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/environmental-indicators/conserved-areas.html#DSM (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- UN General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 21 October 2015, A/RES/70/1. 2015. Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Jones-Walters, L.; Mulder, I. Valuing nature: The economics of biodiversity. J. Nat. Conserv. 2019, 17, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Ocean Economy in 2030; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.J.; Sumaila, U.R. Economic impact of ocean fish populations in the global fishery. J. Bioecon. 2010, 12, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, P.A.L.D.; van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. Economic valuation of biodiversity: Sense or nonsense? Ecol. Econ. 2001, 39, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remoundou, K.; Koundouri, P.; Kontogianni, A.; Nunes, P.A.L.D.; Skourtos, M. Valuation of natural marine ecosystems: An economic perspective. Environ. Sci. Policy 2009, 12, 1040–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual., U.; Muradian, R.; Brander, L.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Martín-López, B.; Verma, M. The economics of valuing ecosystem services and biodiversity. In The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Ecological and Economic Foundations; Kumar, P., Ed.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 183–256. [Google Scholar]

- Pontecorvo, G.; Wilkinson, M.; Anderson, R.; Holdowsky, M. Contribution of the Ocean Sector to the United States Economy. Science 1980, 208, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kildow, J.T.; McIlgorm, A. The importance of estimating the contribution of the oceans to national economies. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, T.M. An approach for integrating economic impact analysis into the evaluation of potential marine protected area sites. J. Environ. Manag. 2004, 70, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, F.; Lamond, J.; Appleby, T. Assessing the significance of the economic impact of Marine Conservation Zones in the Irish Sea upon the fisheries sector and regional economy in Northern Ireland. Mar. Policy 2016, 74, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, G.; Allan, G.; Beaumont, N.; Georgakaki, A.; Hacking, B.; Hooper, T.; Kerr, S.; O’Hagan, A.M.; Reilly, K.; Ricci, P.; et al. Economic and socio-economic assessment methods for ocean renewable energy: Public and private perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 45, 850–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colgan, C.S. Measurement of the Ocean Economy from National Income Accounts to the Sustainable Blue Economy. J. Ocean Coast. Econ. 2016, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDuffee, M.; Rosenberger, A.R.; Dixon, R.; Jarvela Rosenberger, A.; Fox, C.; Paquet, P.C. What’s at Stake: Threatened Ecosystems and Benefits in the Salish Sea; Version 1; Raincoast Conservation Foundation: Sidney, BC, Canada, 2015; p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, C.; McDaniels, T.; Hinch, S. Indigenous culture and adaptation to climate change: Sockeye salmon and the St’át’imc people. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2010, 15, 859–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groesbeck, A.S.; Rowell, K.; Lepofsky, D.; Salomon, A.K. Ancient Clam Gardens Increased Shellfish Production: Adaptive Strategies from the Past Can Inform Food Security Today. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ban, N.; Alder, J. How wild is the ocean? Assessing the intensity of anthropogenic marine activities in British Columbia, Canada. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2008, 18, 55–85. [Google Scholar]

- NOAA. 10 Years of Research & Conservation: Southern Resident Killer Whales. 2014; 24p. Available online: http://komonews.s3.amazonaws.com/140625_orca_report_quality.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Lam, V.W.Y.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Reygondeau, G.; Sumaila, U.R. Project change in global fisheries revenues under climate change. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- GSGislason & Associates. Economic Contribution of the Oceans Sector in British Columbia; GSGislason & Associates: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2007; 64p. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, D. Should BC Lift the Offshore Oil Moratorium? A Policy Brief on the Economic Lessons from Hibernia. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternative. Available online: https://policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/BC_Office_Pubs/offshore_oil.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- NRG Research Group and BC Ministry of Jobs, Tourism and Skills Training. 2009/10 Outdoor Recreation Study BC Resident Participation. 2013. Available online: http://www.destinationbc.ca/getattachment/Research/Research-by-Activity/All-Research-by-Activity/Outdoor-Recreation-Study-2009-2010,-January-2013/Outdoor-Recreation-for-Distribution-14Jan13-FINAL-DRAFT-(2).pdf.aspx (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Bodtker, K.; Shaikh, S.; Towers, J.R.; Scott-Ashe, J.; Robb, C.; Gilliard, G.; Wright, K. Connecting Marine Ecotourism Values in Northern Vancouver Island with Marine Protected Areas; Living Oceans Society: Sointula, BC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- BC Stats Measuring the Size of British Columbia’s Tourism Sector. 2009. Available online: http://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/data/statistics/business-industry-trade/industry/tourism (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Tourism, B.C. Economic Value of the Commercial Nature-Based Tourism Industry in British Columbia. Prepared in Part by Pacific Analytics and Wilderness Tourism Association. 2004. 18p. Available online: https://www.destinationbc.ca/content/uploads/2018/08/Economic_Impacts_of_Commercial_Nature-Based_Tourism_Report-sflb.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Pinfold, G. Economic Impact of Marine Related Activities in Canada. Statistical and Economic Analysis Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ontario. Publication No.1-1. 125p. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2010/mpo-dfo/Fs22-7-1-1-eng.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Government of BC British Columbia Seafood Industry Year in Review 2016. 17p. 2017. Available online: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/farming-natural-resources-and-industry/agriculture-and-seafood/statistics/industry-and-sector-profiles/year-in-review/bcseafood_yearinreview_2016.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- BC Salmon Farmers Association Economic Impact Study of the BC Farm-Raised Salmon Industry. Prepared by MNP LLC, 24p. 2015. Available online: https://bcsalmonfarmers.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/1_BCSFA_2014_EconImpactStudy.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- InterVISTAS. Port of Vancouver 2016 Economic Impact Study; InterVISTAS: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2017; 100p. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Shipping in Canada; Catalogue No. 54-205-X; Minister of Industry: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012; 191p. [Google Scholar]

- LEGG. Marine Industry Benefits Study: Economic Impact of the Canadian Marine Transportation Industry; LEGG: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2004; 108p. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Table 14-10-0023-01 Labour Force Characteristics by Industry, Annual (x 1000); Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Table 36-10-0402-02 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at Basic Prices, by Industry, Provinces and Territories, Growth Rates (x 1,000,000); Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business Research & Economic Advisors. The Economic Contribution of Cruise Tourism in Victoria; Prepared for Greater Victoria Harbour Authority; Business Research & Economic Advisors: Exton, PA, USA, 2013; 12p. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, M.; Kocian, M.; Batker, D. Valuing the Aquatic Benefits of British Columbia’s Lower Mainland: Nearshore Natural Capital Valuation; David Suzuki Foundation and Earth Economics: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2012; 103p. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, C.M.; O’Leary, B.C.; McCauley, D.J.; Cury, P.M.; Duarte, C.M.; Lubchenco, J.; Pauly, D.; Saenz-Arroyo, A.; Sumaila, U.R.; Wilson, R.W.; et al. Marine reserves can mitigate and promote adaptation to climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 6167–6175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Statistics Canada. Table 36-10-0402-01 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at Basic Prices, by Industry, Provinces and Territories (x 1,000,000); Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism, B.C. Fishing Product Overview. 2009. 13p. Available online: http://www.destinationbc.ca/getattachment/Research/Research-by-Activity/Water-based/Fishing_Sector_Profile.pdf.aspx (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Pauly, D.; Zeller, D. Catch reconstructions reveal that global marine fisheries catches are higher than reported and declining. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DFO. Fishing-Related Employment by Industry and Province, 2014–2016. Fisheries and Oceans Canada Statistics. 2018. Available online: http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/stats/cfs-spc/tab/cfs-spc-tab2-eng.htm (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Destination British Columbia. July 2016. Tourism Sector Profile: Cruise. Available online: http://www.destinationbc.ca/getattachment/Research/Research-by-Activity/Water-based/Cruise-Profile-FINAL.pdf.aspx (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Van der Meer, L. Global Revenues from Wild Seafood Products. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Graduate Studies, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2012; 115p. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F. Subsistence Fishing in Canada: A Note on Terminology. Arctic 1998, 41, 319–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schumann, S.; Macinko, S. Subsistence in coastal fisheries policy; What’s in a word? Mar. Policy 2007, 31, 706–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSGislason & Associates. The Marine Economy & the Regional District of Mt. Waddington in BC. In Prepared for Living Oceans Society & Regional District of Mt. Waddington; GSGislason & Associates: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011; 39p. [Google Scholar]

- Chiesura, A.; de Groot, R. Critical natural capital: A socio-cultural perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2003, 44, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M.D. On the relation between ecosystem services, intrinsic value, existence value and economic valuation. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 95, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.O. The Hedonic Method. In A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation; Champ, P.A., Boyle, K.J., Brown, T.C., Eds.; The Economics of Non-Market Goods and Resources; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Cesar, H.S.J.; van Beukering, P.J.H. Economic Valuation of the Coral Reefs of Hawai’i. Pac. Sci. 2004, 58, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teh, L.S.L.; Teh, L.C.L.; Jolis, G. An economic approach to marine megafaua conservation in the coral triangle: Marine turtles in Sabah, Malaysia. Mar. Policy 2018, 89, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, L.E.; McDonough, N.; Austen, M.; Mee, L.; Moore, M.; Hess, P.; Depledge, M.H.; White, M.; Philippart, K.; Bradbrook, P.; et al. Oceans and Human Health: A rising tide of challenges and opportunities for Europe. Mar. Environ. Res. 2014, 99, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selig, E.R.; Hole, D.G.; Allison, E.H.; Arkema, K.K.; McKinnon, M.C.; Chu, J.; de Sherbinin, A.; Fisher, B.; Glew, L.; Holland, M.B.; et al. Mapping global human dependence on marine ecosystems. Conserv. Lett. 2019, 12, e12617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vandermoor, M. Integrated Oceans Management Planning and Policy in Canada: An Evaluation of the Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area Planning Process. Master’s Thesis, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada, 2017; 144p. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Jobs, Tourism and Innovation. The Value of Tourism in British Columbia: Trends from 2000 to 2010. 2012; 42p. Available online: https://www.destinationbc.ca/content/uploads/2018/08/Value-of-Tourism-in-British-Columbia-May-2012.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- B.C. Data Catalogue Industry Statistics. Available online: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/data/statistics (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Regional Outdoor Recreation Opportunities Study for Metro Vancouver and Fraser Valley Regional District, March 10, 2011. Phase 1 Demand Analysis Report. Prepared by LEES + Associates, Mustel Group, Urban Futures. Available online: http://www.metrovancouver.org/services/parks/ParksPublications/Regional%20Outdoor%20Recreation%20Opportunities%20Study%20-%20Phase%20One%20Demand%20Analysis%20Report%20-%20March%202011.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Tourism Vancouver Market Research (1998–2015 Data). Available online: https://res.cloudinary.com/simpleview/image/upload/v1/clients/vancouverbc/cruise_volume_86_15_dbb3a2a0-d504-4d46-ba6d-51e38be5029f.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Port Metro Vancouver Cruise Statistics Report 2008–2015. Available online: https://www.portvancouver.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Cruise-Statistics-Monthly-2008-to-2015.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Survey of Recreational Fishing in Canada 2010; DFO: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012; 27p. [Google Scholar]

- GSGislason & Associates. British Columbia Seafood Sector and Tidal Water Recreational Fishing: A Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats Assessment; Final Report; GSGislason & Associates: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2004; 234p. [Google Scholar]

- DataBC. BC Seafood Harvest, Landed and Wholesale Value. Available online: https://catalogue.data.gov.bc.ca/dataset/bc-seafood-harvest-landed-and-wholesale-value (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Statistics Canada Data. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/type/data?MM=1 (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Principal Statistics for Manufacturing Industries, Annual Survey of Manufacturing and Logging Industries, Seafood Product Preparation and Packaging [NAICS 3117]. Available online: https://www.ic.gc.ca/app/scr/app/cis/manufacturing-fabrication/3117;jsessionid=0001Qc0fcTt1toHK18lFR6gb2hi:-C7AEJO?wbdisable=true (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Ecotrust Canada. Briefing: A Cautionary Tale about ITQs in BC Fisheries; Ecotrust Canada: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- BC Ministry of Agriculture. 2011. Available online: http://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/farming-natural-resources-and-industry/agriculture-and-seafood/statistics/industry-and-sector-profiles/employment/2011_british_columbia_fish_processing_employment_survey_results.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Stroomer, C.; Wilson, M. British Columbia’s Fisheries and Aquaculture Sector, 2012 ed.; BC Stats: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2013; 98p. [Google Scholar]

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Survey of Recreational Fishing in Canada; Fisheries and Oceans Canada: Ottawa, ON, USA, 2005; Available online: http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/stats/rec/can/2005/REC2005_EN_20070727.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2022).

| Ocean Based Activity | Benefit (Output) from Activity | Producer (Beneficiary) | Revenue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild fisheries | Fish catch | Fishers | Landed value |

| Recreational fishing (residents and nonresidents) | Fish catch, fishing experience | Recreational fisher (producer); Local businesses (beneficiary) | Expenditure by recreational fisher |

| Seafood processing | Seafood product | Seafood processors/buyers | Wholesale value |

| Whale watching | Whale/wildlife sighting | Whale watching companies | Fees paid by participants |

| Ocean-side activities (locals, tourists) | Purchase of land-based goods and services | Port city (travel, accommodation, food, equipment, etc.) | Expenditure by tourists and locals |

| Kayaking/canoeing (self-guided) | Kayaking experience | Kayaker (producer); Local businesses (beneficiary) | Expenditure by kayaker (travel, gear rental, etc.) |

| Cruise lines | Purchase of land-based goods and services | Port of call | Expenditure by cruise vessels, passengers and crew |

|

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teh, L.C.L.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Sumaila, R. Assessing the Economic Contribution of Ocean-Based Activities Using the Pacific Coast of British Columbia as a Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148662

Teh LCL, Cheung WWL, Sumaila R. Assessing the Economic Contribution of Ocean-Based Activities Using the Pacific Coast of British Columbia as a Case Study. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148662

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeh, Lydia C. L., William W. L. Cheung, and Rashid Sumaila. 2022. "Assessing the Economic Contribution of Ocean-Based Activities Using the Pacific Coast of British Columbia as a Case Study" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148662

APA StyleTeh, L. C. L., Cheung, W. W. L., & Sumaila, R. (2022). Assessing the Economic Contribution of Ocean-Based Activities Using the Pacific Coast of British Columbia as a Case Study. Sustainability, 14(14), 8662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148662