Rural Residents’ Intention to Participate in Pro-Poor Tourism in Southern Xinjiang: A Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

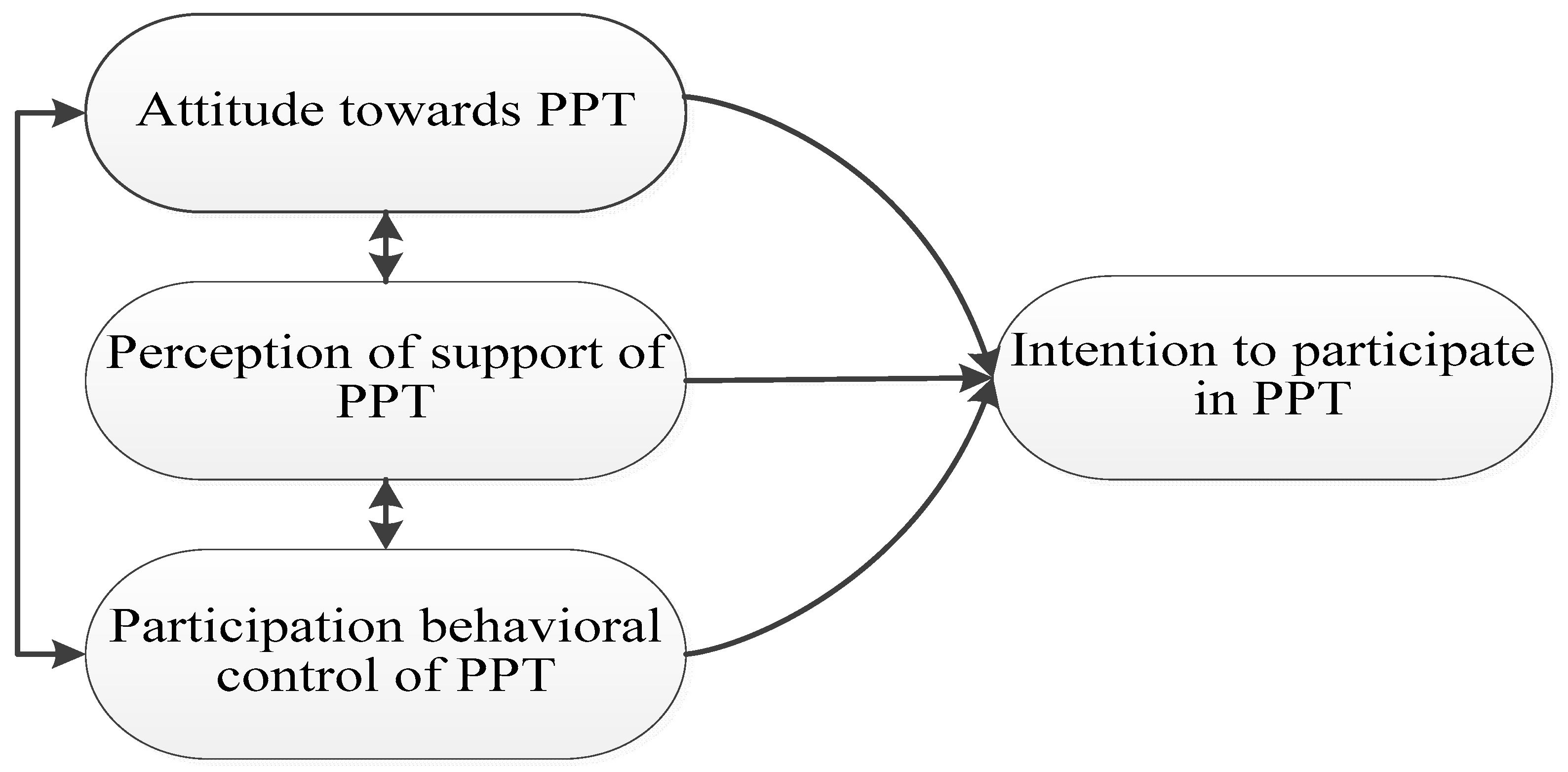

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Context

3.2. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Regression Analysis

4.3. Analysis of Influencing Factors

- (1).

- Analysis of attitude towards PPT

- (2).

- Analysis of perception of support for PPT

- (3).

- Analysis of participation behavioral control of PPT

- (4).

- Analysis of personal characteristics

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goodwin, H. Pro-poor tourism: A response. Third World Q. 2008, 29, 869–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventi, C.; Sutherland, H.; Tasseva, I.V. Improving poverty reduction in Europe: What works best where? J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2019, 29, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spenceley, A.; Meyer, D. Tourism and poverty reduction: Theory and practice in less economically developed countries. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 297–317. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, D.; Xu, H.; Chung, Y. Perceived impacts of the poverty alleviation tourism policy on the poor in China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 41, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R.; Naidoo, P. Tourism and poverty reduction: The case of Mauritius. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2010, 7, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D. Pro-poor tourism: Looking backward as we move forward. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2014, 11, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoya, E.T.; Seetaram, N. Tourism contribution to poverty alleviation in Kenya: A dynamic computable general equilibrium analysis. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Winkler, C.; Wang, S.; Chen, H. Regional determinants of poverty alleviation through entrepreneurship in China. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2020, 32, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Xia, X. Tourism and poverty reduction: Empirical evidence from China. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, P.; Aguirre-Padilla, N.; Oliveira, C.; Álvarez-García, J.; del Río-Rama, M.d.l.C. The spatial externalities of tourism activities in poverty reduction. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D. Pro-poor tourism: From leakages to linkages. A conceptual framework for creating linkages between the accommodation sector and ‘poor’ neighbouring communities. In Tourism and the Millennium Development Goals; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; pp. 131–156. [Google Scholar]

- Sudsawasd, S.; Charoensedtasin, T.; Laksanapanyakul, N.; Pholphirul, P. Pro-poor tourism and income distribution in the second-tier provinces in Thailand. Area Dev. Policy 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Do indexes assess poverty? Is tourism truly pro-poor? J. Ekon. 2022, 4, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Wang, G.; Marcouiller, D.W. A scientometric review of pro-poor tourism research: Visualization and analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, B.; Ryan, C. Assisting the poor in China through tourism development: A review of research. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muganda, M.; Sahli, M.; A Smith, K. Tourism’s contribution to poverty alleviation: A community perspective from Tanzania. Dev. S. Afr. 2010, 27, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, C.; Boyd, C.; Goodwin, H. Pro-Poor Tourism: Putting Poverty at the Heart of the Tourism Agenda; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M. Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict tourism destination revisit intention. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2021, 22, 524–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, S.S.; Catacutan, D.; Sileshi, G.W.; Nieuwenhuis, M. Tree planting by smallholder farmers in Malawi: Using the theory of planned behaviour to examine the relationship between attitudes and behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A. The theory of planned behavior and microfinance participation: From the perspective of nonparticipating rural poor in Bangladesh. Res. J. Financ. Account. 2014, 5, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T.J. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Tölkes, C.; Butzmann, E. Motivating pro-sustainable behavior: The potential of green events—A case-study from the Munich Streetlife Festival. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Popa, A.; Sun, H.; Guo, W.; Meng, F. Tourists’ Intention of Undertaking Environmentally Responsible Behavior in National Forest Trails: A Comparative Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, Z.-A.; Shalbafian, A.A.; Allam, Z.; Ghaderi, Z.; Murgante, B.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R. Enhancing Memorable Experiences, Tourist Satisfaction, and Revisit Intention through Smart Tourism Technologies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Gendered theory of planned behaviour and residents’ support for tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 525–540. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, K.; Shen, H. Chinese traditional village residents’ behavioural intention to support tourism: An extended model of the theory of planned behaviour. Tour. Rev. 2020, 76, 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.K.F.; Wu, H.; Kim, S. Residents’ perceptions of tourism influence and intention to support tourism development: Application of the theory of planned behavior. J. China Tour. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Geng, B.; Zhuang, T.; Yang, H. Research on impoverished Tibetan farmers’ and herders’ willingness and behavior in participating in pro-poor tourism: Based on a survey of 1320 households in 23 counties (cities) in the Tibetan areas of Sichuan Province. Tour. Trib. 2017, 32, 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D.; Ouyang, Z.; Nunkoo, R.; Wei, W. Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes towards tourism development: A meta-analysis. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Lin, H.; Zhang, C. Locally situated rights and the ‘doing’of responsibility for heritage conservation and tourism development at the cultural landscape of Honghe Hani Rice Terraces, China. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, D.W. An institutional analysis of local strategies for enhancing pro-poor tourism outcomes in Cuzco, Peru. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, C.; Roe, D. Pro-Poor Tourism Strategies: Making Tourism Work for the Poor: A Review of Experience; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vedeld, P.; Angelsen, A.; Bojö, J.; Sjaastad, E.; Berg, G.K. Forest environmental incomes and the rural poor. For. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 869–879. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Wang, S.; Tuo, S.; Du, J. Analysis of the effect of rural tourism in promoting farmers’ income and its influencing factors–Based on survey data from Hanzhong in Southern Shaanxi. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zuo, Y.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Impact of farmers’ participation in tourism on sustainable livelihood outcomes in border tourism areas. Int. Sociol. 2022, 37, 50–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Geng, C.; Su, X. Antecedents of residents’ pro-tourism behavioral intention: Place image, place attachment, and attitude. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Mi, Z.; Zhang, Z. Willingness of the new generation of farmers to participate in rural tourism: The role of perceived impacts and sense of place. Sustainability 2020, 12, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, H.; Ye, S. Being rational and emotional: An integrated model of residents’ support of ethnic tourism development. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yujing, C.; Songmao, W.; Zhaoli, H.; Tong, D. A study on minority women’s willingness to participate in tourism poverty alleviation and its influencing factors: A case study of Kazak in Xinyuan County. Int. J. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2020, 29, 1458. [Google Scholar]

- Sirivongs, K.; Tsuchiya, T. Relationship between local residents’ perceptions, attitudes and participation towards national protected areas: A case study of Phou Khao Khouay National Protected Area, central Lao PDR. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 21, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mosquera, N. Gender differences, theory of planned behavior and willingness to pay. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D. Place attachment, perception of place and residents’ support for tourism development. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2018, 15, 188–210. [Google Scholar]

- Erul, E.; Woosnam, K.M.; Mcintosh, W.A. Considering emotional solidarity and the theory of planned behavior in explaining behavioral intentions to support tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1158–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-T.; Chen, Y.-S. Local intentions to participate in ecotourism development in Taiwan’s Atayal communities. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2018, 16, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colautti, L.; Cancer, A.; Magenes, S.; Antonietti, A.; Iannello, P. Risk-perception change associated with COVID-19 Vaccine’s side effects: The role of individual differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampedi, I.T.; Ifegbesan, A.P. Understanding the determinants of pro-environmental behavior among South Africans: Evidence from a structural equation model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyeampong, O.A. Pro-poor tourism: Residents’ expectations, experiences and perceptions in the Kakum National Park Area of Ghana. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, F.; Wang, Z.; Shuai, C. What is the anti-poverty effect of solar PV poverty alleviation projects? Evidence from rural China. Energy 2021, 218, 119498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D.; Hall, C.M.; Garry, T. Tourism and poverty alleviation: Perceptions and experiences of poor people in Sapa, Vietnam. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 1071–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talinbayi, S.; Xu, H.; Li, W. Impact of yurt tourism on labor division in nomadic Kazakh families. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2019, 17, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Huang, S.; Ding, P. Toward a community-driven development model of rural tourism: The Chinese Experience. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetschmann, G.; Ballantyne, A.; Staub, K.E.; Winkelmann, R. feologit: A new command for fitting fixed-effects ordered logit models. Stata J. 2020, 20, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. Understanding and interpreting generalized ordered logit models. J. Math. Sociol. 2016, 40, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, W.; Shengmin, Y.; Wei, X. Ologit-based analysis of factors affecting campus football performance. J. Shanghai Univ. Sport 2019, 43, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson, C.M. Pro-poor local economic development in South Africa: The role of pro-poor tourism. Local Environ. 2006, 11, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X. Growth, Inequality, and Poverty in Rural China: The Role of Public Investments; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; Volume 125. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Xiang, P.; Zhang, R.; Chen, D.; Ren, Y. Mediating effect of risk propensity between personality traits and unsafe behavioral intention of construction workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Ren, Y.; Xiong, N.; Li, H.; Chen, Y. Why small towns can not share the benefits of urbanization in China? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.V.; Duflo, E. The economic lives of the poor. J. Econ. Perspect. 2007, 21, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyathi, M.D. Social Exclusion as a Barrier to Poverty Reduction: The Case of Basarwa in Botswana; University of KwaZulu-Natal: Durban, South Africa, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tilak, J.B. Education poverty in India. In Education and Development in India; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 87–162. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ngo, Q.-T.; Iqbal, W. Role of education in poverty reduction: Macroeconomic and social determinants form developing economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 63163–63177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasudawan, K.; Ab-Rahim, R. Pro-Poor Tourism and Poverty Alleviation in Sarawak. Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, J. Path dependence in pro-poor tourism. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 973–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, U.C.; Ehiobuche, C.; Igwe, P.A.; Agha-Okoro, M.A.; Onwe, C.C. Women entrepreneurship and poverty alleviation: Understanding the economic and socio-cultural context of the Igbo women’s basket weaving enterprise in Nigeria. J. Afr. Bus. 2021, 22, 448–467. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, O.; Cicowiez, M.; Gachot, S. A quantitative framework for assessing public investment in tourism–An application to Haiti. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.L. What is field theory? Am. J. Sociol. 2003, 109, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Title | Author (Year) | Respondents | Related Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedents of residents’ pro-tourism behavioral intention: Place image, place attachment, and attitude | [38] | Residents in Huangshan, China (N = 370) | Residents’ attitude towards tourism was positively related to their PPT behavioral intention. |

| Willingness of the new generation of farmers to participate in rural tourism: The role of perceived impacts and sense of place | [39] | Farmers in Yanling County, China (N = 263) | Perceived impacts of rural tourism positively affected residents’ willingness to participate in tourism activities. |

| Being rational and emotional: An integrated model of residents’ support of ethnic tourism development | [40] | Residents in Xijiang Miao Village, Leishan County, Guizhou Province, China (N = 294) | Residents’ perceived benefits positively influenced their support for tourism development. |

| Research on impoverished Tibetan farmers’ and herders’ willingness and behavior in participating in pro- poor tourism: Based on a survey of 1320 households in 23 counties (cities) in the Tibetan areas of Sichuan province | [30] | Farmers and herdsmen in Tibetan areas of Sichuan (N = 1320) | The attitude of poor farmers and herders towards PPT had a positive impact on their participation behavior; the support perception of important others had a significant positive impact on their willingness to participate in PPT; perceived behavioral control had a significant positive impact on their willingness to participate in PPT. |

| A study on minority women’s willingness to participate in tourism poverty alleviation and its influencing factors: A case study of Kazak in Xinyuan County | [41] | Minority Women in Xinyuan County, China (N = 660) | Tourist souvenir-making skills, government attention to tourism poverty alleviation, economic income supporting the participation in PPT, and family support for working out had a significant positive impact on Kazakh women’s willingness to participate in PPT. |

| Relationship between local residents’ perceptions, attitudes and participation towards national protected areas: A case study of Phou Khao Khouay National Protected Area, central Lao PDR | [42] | Residents in Phou Khao Khouay National Protected Area (N = 405) | Residents’ positive perceptions affected their attitudes, while positive attitudes strongly influenced their participation in NPA activities. |

| Gender differences, theory of planned behavior and willingness to pay | [43] | Visitors in Monfragüe National Park, Spain (N = 200) | Visitors’ subjective norms had a positive influence on their willingness to pay for the conservation of the park. |

| Chinese traditional village residents’ behavioral intention to support tourism: an extended model of the theory of planned behavior | [28] | Residents of Hongcun Village, Anhui Province, China (N = 406) | Residents’ subjective norms had a positive effect on their behavioral intention to support tourism. |

| Place attachment, perception of place and residents’ support for tourism development | [44] | Residents in Kavala, Greece (N = 481) | Residents’ perception of place positively affected their perception of tourism impacts, which positively influenced their support for tourism development. |

| Considering emotional solidarity and the theory of planned behavior in explaining behavioral intentions to support tourism development | [45] | Residents in Izmir (Turkey) (N = 740) | Perceived behavioral control significantly predicted their behavioral intentions to support tourism development. |

| Local intentions to participate in ecotourism development in Taiwan’s Atayal communities | [46] | Residents in three Atayal communities in Yilan County, Taiwan (N = 301) | Perceived behavioral control had a positive influence on the residents’ behavioral intentions to participate in ecotourism development. |

| Variables | Classification | Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 517 | 51.09% | 51.09% |

| Female | 495 | 48.91% | 100% | |

| Age | 16–24 years old | 177 | 17.49% | 17.49% |

| 25–34 years old | 296 | 29.25% | 46.74% | |

| 35–44 years old | 271 | 26.78% | 73.52% | |

| 45–54 years old | 236 | 23.32% | 96.84% | |

| 55 years old or older | 32 | 3.16% | 100% | |

| Ethnic group | Uygur nationality | 313 | 30.93% | 30.39% |

| Kazak nationality | 26 | 2.57% | 33.50% | |

| Kirgiz nationality | 261 | 25.79% | 59.29% | |

| Tajik nationality | 357 | 35.28% | 94.57% | |

| Han nationality | 23 | 2.27% | 96.85% | |

| Other | 32 | 3.16% | 100% | |

| Education level | Below primary school | 86 | 8.50% | 8.50% |

| Primary school | 306 | 30.24% | 38.74% | |

| Junior high school | 302 | 29.84% | 68.58% | |

| High school and technical secondary school | 211 | 20.85% | 89.43% | |

| College degree or above | 107 | 10.57% | 100% | |

| Mandarin level | Unable to communicate | 312 | 30.83% | 30.83% |

| Basic oral communication without writing | 305 | 30.14% | 60.97% | |

| Basic oral communication with basic writing | 227 | 22.43% | 83.40% | |

| Fluent in listening and speaking | 110 | 10.87% | 94.27% | |

| Accurate writing, fluent listening and speaking | 58 | 5.73% | 100% | |

| Satisfaction with personal health status | Very dissatisfied | 61 | 6.03% | 6.03% |

| Dissatisfied | 184 | 18.18% | 21.21% | |

| Moderate satisfaction | 241 | 23.81% | 48.02% | |

| Satisfied | 316 | 31.23% | 79.25% | |

| Very satisfied | 210 | 20.75% | 100% | |

| Per capita cultivated land area | ≥1.38 mu | 188 | 18.58% | 18.58% |

| 0.8–1.38 mu | 442 | 43.68% | 62.26% | |

| ≤0.8 mu | 383 | 37.85% | 100% | |

| Main sources of income | Government grants | 496 | 49.01% | 49.01% |

| Fixed-wage income | 324 | 32.02% | 81.03% | |

| Independent operation | 192 | 18.97% | 100% | |

| Main sources of income before tourism development | Animal husbandry | 256 | 25.29% | 25.29% |

| Crop planting | 134 | 13.24% | 38.53% | |

| Forest and fruit planting | 255 | 25.20% | 63.71% | |

| Handicraft industry | 279 | 27.60% | 91.31% | |

| Other | 88 | 8.70% | 100% | |

| Willingness towards ways to participate in tourism | Provide catering raw materials | 80 | 7.90% | 7.90% |

| Self-operated farmhouse | 105 | 10.38% | 18.28% | |

| Independent ethnic flavor restaurant | 133 | 13.14% | 31.42% | |

| Self-operated B&B | 94 | 9.29% | 40.71% | |

| Scenic-spot work | 124 | 12.25% | 52.96% | |

| Hotel staff | 34 | 3.36% | 56.32% | |

| Travel agency staff | 99 | 9.78% | 66% | |

| Tour guide | 96 | 9.49% | 75.59% | |

| Small-commodity management | 106 | 10.47% | 86.06% | |

| Proportion of tourism income in family income | ≤10% | 459 | 45.36% | 45.36% |

| 11%–20% | 216 | 21.34% | 66.70% | |

| 21%–30% | 188 | 18.58% | 85.28% | |

| 31%–40% | 89 | 8.79% | 94.07% | |

| ≥40% | 60 | 5.93% | 100% | |

| Number of tourism training sessions received in a year | 0 times | 241 | 23.81% | 23.81% |

| 1 time | 316 | 31.23% | 55.04% | |

| 2 times | 210 | 20.75% | 75.79% | |

| 3 times | 184 | 18.18% | 93.97% | |

| ≥4 times | 61 | 6.03% | 100% |

| Items and Constructs | Mean | Std. |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude towards PPT | 3.22 | 1.42 |

| PPT helps to increase my employment opportunities | 3.24 | 1.55 |

| PPT helps to increase my income | 3.21 | 1.52 |

| PPT helps to improve my life skills | 3.21 | 1.53 |

| Perception of support for PPT | 3.12 | 0.66 |

| I am satisfied with the tourism service materials provided by the government | 3.28 | 1.09 |

| I am satisfied with the number of tourism training provided by government and tourism enterprises | 3.28 | 1.07 |

| I am satisfied with the incentive of pioneer of PPT | 2.80 | 1.23 |

| Participation behavioral control of PPT | 3.22 | 1.41 |

| I have full confidence in local tourism resources | 3.27 | 1.53 |

| I have opportunity to participate in PPT | 3.23 | 1.57 |

| I think the local tourism industry is extremely fragile | 3.27 | 1.51 |

| Intention to participate in PPT | 3.26 | 1.06 |

| VARIABLES | Intention to Participate in PPT | VARIABLES | Intention to Participate in PPT |

|---|---|---|---|

| (OLOGIT, Model 1) | (OLS, Model 2) | ||

| Attitude towards PPT | 0.489 *** | Attitude towards PPT | 0.220 *** |

| −4.52 | −4.66 | ||

| Perception of support for PPT | −0.102 | Perception of support for PPT | −0.038 |

| (−1.13) | (−0.97) | ||

| Participation behavioral control of PPT | 0.509 *** | Participation behavioral control of PPT | 0.224 *** |

| −4.67 | −4.72 | ||

| Age | 0.013 | Age | 0.002 |

| −0.25 | −0.08 | ||

| Education level | 0.025 | Education level | 0.057 |

| −1.12 | −1.09 | ||

| Mandarin level | −0.087 * | Mandarin level | −0.043 ** |

| (−1.79) | (−2.02) | ||

| Satisfaction with personal health status | −0.009 | Satisfaction with one’s own health | −0.006 |

| (−0.18) | (−0.27) | ||

| Annual household income | −0.018 | Annual household income | −0.001 |

| −0.37 | −0.49 | ||

| Housing structure | 0.018 | Housing structure | 0.007 |

| −0.37 | −0.34 | ||

| Residential location | 0.018 | Residential location | −0.005 |

| −0.31 | (−0.21) | ||

| Proximity of residence to scenic spot | 0.065 ** | Proximity of residence to scenic spot | 0.094 |

| −2.02 | −2.33 | ||

| N | 1012 | N | 1,012 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.169 | R-squared | 0.791 |

| Log likelihood | −1195.4906 | r2_a | 0.784 |

| LRx2 | 486.22 | F | 58.38 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Liao, Y.; Gao, J. Rural Residents’ Intention to Participate in Pro-Poor Tourism in Southern Xinjiang: A Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8653. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148653

Wang Q, Liao Y, Gao J. Rural Residents’ Intention to Participate in Pro-Poor Tourism in Southern Xinjiang: A Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8653. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148653

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qi, Yue’e Liao, and Jun Gao. 2022. "Rural Residents’ Intention to Participate in Pro-Poor Tourism in Southern Xinjiang: A Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8653. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148653

APA StyleWang, Q., Liao, Y., & Gao, J. (2022). Rural Residents’ Intention to Participate in Pro-Poor Tourism in Southern Xinjiang: A Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective. Sustainability, 14(14), 8653. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148653