Abstract

Due to the COVID-19 epidemic, ordering food online has become very popular. This study used a structural equation model to analyze the indicators that influence the decision to order food through a food-delivery platform. The theory of planned behavior and the technology acceptance model were both used, along with a new factor, the task–technology fit (TTF) model, to study platform suitability. Data were collected using a questionnaire given to a group of 1320 consumers. The results showed that attitudes toward on-line delivery most significantly affected the behavioral intentions of the consumers, followed by subjective norms. Among attitudes, perceived ease of use was the most significant, followed by perceived usefulness and trust. The study’s results revealed that TTF had the most significant impact on perceived ease of use, followed by perceived usefulness. This means that, if a food-ordering platform is deemed appropriate, consumers will continue to use it, and business sustainability will be enhanced.

1. Introduction

The Internet has generated such convenience and speed [1] to our lives that our world has become an online world. In other words, the acceptance and use of the Internet is pervasive [2,3,4]. In 2018, Thais used the Internet on average 10 h and 5 min per day, an increase of 3 h and 30 min over the previous year. The five most popular Internet features were social media (96.3%), email (74.2%), information searching (70.8%), TV, other video entertainment, and music (60.7%) access, and shopping (51.3%). In addition, Thais completed more tasks online (69.1%), such as reserving hotel rooms, purchasing tickets, and paying for goods and services—including food delivery—compared to completing just 30.9% of these tasks offline. In 2017, the proportions were 52.5 and 47.5%, respectively. From 2014 to 2018, the Thai food-delivery business experienced average an annual growth of 7.7%, rising in value from THB 23,640 million to THB 31,814 million [5].

After the COVID-19 outbreak, Thai authorities imposed drastic measures, that included temporarily shutting down or restricting businesses. Restaurants were only allowed to sell food for takeout or delivery. In the first half of 2020, home delivery via on-line platforms increased by about 150% over the previous year. After the pandemic abated and restaurant dining resumed, the volume of home delivery food was not as high, but still higher than before the pandemic—66–68 million deliveries—for an annual growth of 78.0–84.0% [6]. Because the purchase of goods through apps is so fast and easy, online purchases also represent a growth opportunity for digital service businesses, such as food and parcel delivery. In particular, online food delivery increased more than three times compared to the same period of the previous year, a trend that is reflected in the use of Google to search for e-commerce and logistics, parcel delivery, and online food delivery [7].

Additionally, the food-service industry experienced growth amid the pandemic and associated lockdowns. In Thailand and elsewhere, the number of restaurants, couriers, and customers joining these platforms in 2020 increased dramatically. As a result, food-delivery platforms worldwide became more profitable [8].

From a review of the literature, most studies on online food delivery through applications focused on marketing mix, service satisfaction, and application selection factors: drone food delivery [9], channels that affect the intent to use food-delivery platforms (Taiwan) [10], consumer innovation motivations in drone food delivery before and after the outbreak [11], online food delivery (Bangladesh) [12], psychological advantages of using greener drone food-delivery services [13], customer satisfaction and continued intention to order online [14], predicting online food-delivery satisfaction and intention [15], comparison of food-delivery services and customer preferences [16], gaps in behavioral control, trust, and satisfaction in organic food consumption [17], risks of drone food delivery before and after the pandemic [11], anti-innovation perspectives related to food-ordering apps [18], the use of drone food delivery services [19], food ordering from fast-food restaurants (China) [20], sustainable digital food purchasing [21], web mining to evaluate the effect of food-delivery ordering on the consumer [22], eco-friendly and value-model drone food-delivery service, scrutinizing product involvement [23], application aesthetics in the use of a food-ordering application [24], the role of a food-ordering application in developing satisfaction and brand loyalty during the pandemic [25], and the behavioral intent of using food-delivery apps [26] and food delivery during the pandemic [27].

There have also been studies on the technology adoption model (TAM) examining customer attitudes regarding ordering food online [28], factors influencing the intent to use food delivery apps [29], reasons why consumers purchase food through a food-delivery application [30], acceptance of purchasing clothing via mobile devices (China) [31], attitudes and intentions of customers using smartphone chatbots for shopping [32], the TAM for mobile health care [33], online shopping behaviors of middle-aged adults [34], willingness of young consumers to purchase environmentally friendly products in developing countries [35], consumer attitudes and intentions toward healthy food (Norway) [36], healthy food purchase intentions (Korea), including the behavior of consumers toward buying organic milk [37], online food delivery using the TAM and the technology process and business (TPB) theory [38], the differences between Generation Y males and females regarding online auctions by applying TPB theory [39], and the role of social distancing in mobile shopping acceptance [40] using both the TAM and TPB.

This study used TPB, TAM, and TTF theories to evaluated consumers using online food ordering services. From the review of the past research, it was found that no re-searchers have conducted studies using all three theories; TPB and TAM have been studied together, but both of these methods only study consumer behavior. Therefore, this research further studies the TTF theory to determine whether or not the online food ordering application is suitable for online food ordering services. In this regard, entrepreneurs can use the research results to develop strategies to continuously encourage consumers to use the service. No research had been conducted on the use of TTF with the TAM and TPB. Research related to TTF for ordering food through apps has been concerned with the repeated use of food-delivery apps [41], consumers’ attitudes and behavior toward Internet-enabled TV shopping [42], and extending the TAM–TTF theory through the application of telematics [43]. The three studies found that the TTF factor provided positive research results. Companies that operate a food-ordering application platform can apply our results to develop policies related to consumer demand. If more consumers turn to online food-ordering, such companies will generate more sales. A review of the research into food delivery and sustainable development goals found that consumer behavior studies are still in the early stages (e.g., there was not much use for drone food delivery. As a result, business owners were required to do a significant amount of marketing [44]. The article “Supply Chain Sustainability During COVID-19: Last Mile Food Delivery in China” analyzed factors affecting consumer acceptance for sustainability in business operations [45], specifically, the last mile of online food delivery on the Glovo platform.

The research question for this study concerned factors affecting consumer behavioral intention of online food ordering in Thailand. For this evaluation, we used data collection and statistical model development. Section 2 is a literature review. Section 3 describes the research and methodology. Section 4 presents our findings. Section 5 is the discussion. Section 6 outlines our conclusion. Section 7 describes the limitations of our research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definitions about Food Delivery through Apps

Food-delivery apps are a part of a technology change known as “digital disruption.” They not only change consumer behavior, but also change restaurant business operations. In addition, they play an important role in expanding the food-delivery business. From 2014 to 2018, the average annual growth rate was around 10%, which is only 3–4% higher than the overall average annual restaurant growth rate [46].

Food-delivery apps (FDAs) are an emerging online to offline (O2O) mobile technology that mediates between catering organizations and customers through online ordering and offline delivery services. FDAs are classified into two types [47]: chain restaurants, such as KFC, Domino’s, and Pizza Hut, where customers can order online; and third-party platforms, such as Uber Eats, Zomato, and Baidu Waimai [48].

According to Wang [49], “Mobile food ordering apps are mobile apps that users can download and use as a convenient way to access restaurants, view menus, order and pay without interacting with restaurant staff.”

2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

TPB is a behavioral science theory that predicts and analyzes individual behavior [50]. It was developed from the theory of reasoned action (TRA) by Fishbein and Ajzen. It describes human behavior based on the premise that human beings are logical, use information systematically, and consider consequences before deciding to perform an action [51].

However, Ajzen [50] found that the TRA is of limited use for predicting behaviors over which an individual has incomplete volitional control. He or she is unable to decide whether to perform an action that requires other opportunities or resources, such as money, time, skills, or cooperation from others. In 1985, Ajzen proposed the TPB, which differed from the TRA by adding perceived behavior control. The theory further explained that individuals plan their behaviors, and that successful achievement results from the intent to control factors that obstruct behavior. Most behaviors are under volitional control, which consists of three factors: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control.

Tandon, Kaur, Bhatt, Mäntymäki, and Dhir [30], and Troise, O’Driscoll, Tani, and Prisco [38] confirmed the studies which showed that the main predictor of a customer’s attitude toward online food delivery was behavioral intention toward online shopping. Several studies highlighted the use of apps to buy food and the importance of attitude (ATT) in explaining behavioral intention (BI) [9,19,52,53,54,55,56]. These factors were used to develop the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Attitude positively influences the behavioral intention to order food online.

The subjective norm (SN) is “the perception of social pressure to act or not to take action” [50]. It is also a factor related to using FDAs [48]. The researchers found a significant positive correlation between SN and BI in food-delivery services and online shopping [38,48,57]. Thus, the second hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The subjective norm positively influences the behavioral intention to order food online.

According to the TPB model, perceived behavioral control (PBC) may also influence BI [58]. PBC is defined as “a subjective level of control over the effectiveness of behavior itself.” Various studies have confirmed that PBC is a relevant factor in BI to order food online. For example, one study revealed the importance of considering PBC in BI analysis to buy food online [38]. Thus, the third hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Perceived behavioral control positively influences the behavioral intention to order food online.

In TPB, SN is the primary factor of ATT. When customers recognize that their friends, family, and other related parties have a positive attitude toward online food ordering, they will be more willing to receive such food. Several studies have found that this relationship is important for the acceptance of online or mobile food purchases [38,57]. Thus, the fourth hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Subjective norms positively influence attitude toward ordering food online.

2.3. Technology Acceptance Model

Customers accept emerging technologies in a variety of ways [59]. The TAM, adapted from the TRA, is a well-known theory that researchers use to describe behavioral intention, and it can be used to study information technology acceptance.

The TAM is a factor that determines each individual’s perception of how information and communications technology (ICT) helps contribute to improving operational efficiency and directly affects the BI for repeated use. The TAM can provide insight into the acceptance of technology for its functions and the usefulness of ICT. Many previous studies considered the factors influencing consumers’ attitudes toward ordering food online. For example, the authors of [28] analyzed customer attitudes in the process of food-delivery application, and Davis [60] identified two principles of cognitive response for predicting ATT: perceived ease of use (PEOU) and perceived usefulness (PU). According to Davis [61], PEOU is “the degree to which an individual believes the use of a particular system will be effortless.” For FDAs, this refers to factors influencing behavioral intentions to use a food-ordering app, and to choose an FDA [29,56]. PU, in this case, refers to the perceived usefulness of apps for food ordering [38,56].Therefore, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Perceived ease of use positively influences the attitude toward ordering food online.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Perceived usefulness positively influences the attitude toward ordering food online.

Several scholars have shown that trust (TR) influences ATT, and trust in the mobile app is a crucial factor in O2O commercialization in food delivery [52]. It showed that TR influenced ATT in the same way that the study in [38] confirmed these results. In addition, TR has a great influence on ATT. Thus, the seventh hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Trust positively influences the attitude toward ordering food online.

Many scholars [38,48] have studied how PEOU influences PU; therefore, the eighth hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Perceived ease of use positively influences the perceived usefulness of ordering food online.

In addition, this research added the TTF theory and technology characteristics to determine if the food-ordering platform was suitable. TTF theory is used to assess technology effectiveness, [62] its impact on work operations, and its matching of job requirements to technology characteristics. If it is insufficiently useful, it will not be used [63]. Consistent with the research of [64], extending the TAM–TTF theory with telematics [43] confirmed that TTF affected PEOU and PU. Therefore, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Task–Technology Fit positively influences the perceived ease of ordering food online.

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

Task–Technology Fit positively influences the perceived usefulness of ordering food online.

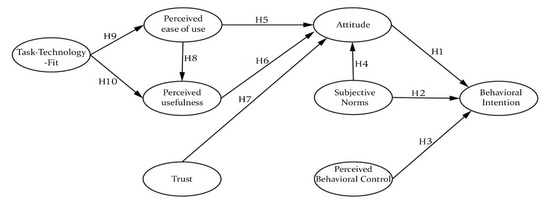

Based on the H1–H10 hypotheses, we established a conceptual framework of relevant studies on factors affecting behavioral intentions to order food delivery, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework.

From a review of related research to test the structural correlation between factors related to attitudes and consumer behavior and other related studies, most articles focused on consumer attitudes and behaviors. The details of these factors are related to the TAM theory and the TPB, as shown in Table 1, which presents a review of research related to the structural relationship between factors related to consumer attitudes and behaviors using analytical methods. These methods are confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), structural equation modeling (SEM), analysis of variance (ANOVA), partial least square SEM (PLS-SEM), and the covariance-based approach (CB-SEM).

Table 1.

Types of relationships found in studies of the technology acceptance model (TAM) theory, the theory of planned behavior (TPB), and other related topics.

2.4. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Sustainable development is designed to meet the needs of the current generation without sacrificing the ability to respond to the needs of the next. It has three key components: economic growth, social inclusion, and environmental protection.

This research responds to the SDGs: decent work and economic growth—the online food-ordering market is growing, and as a result, the economy continues to grow; and responsible consumption and production—online food ordering is highly responsive to consumers because they can order anywhere, anytime. This results in business sustainability in line with the SDGs and the master plan under the country’s national strategy [65].

3. Research and Methodology

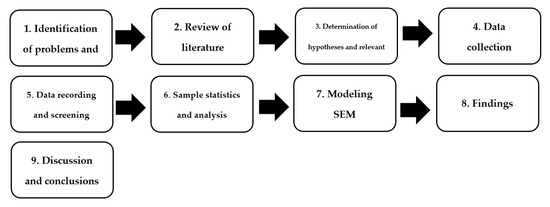

This research studied consumer behavior to suggest guidelines for developing a food-ordering application. There are nine steps in the operation process, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Operational process.

3.1. Data Collections

- Questionnaire design: The questionnaire was divided into 3 parts. Part 1 concerned personal and household characteristics of the respondents (sex, age, highest education level, occupation, average income) and their experience with using food-ordering services apps. Part 2 concerned the behavior of users ordering food through food-ordering apps. Part 3 involved other suggestions related to the use of food-ordering apps.

- Scale: Part 2 consisted of 22 items, assessed on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Although these are ordinal variables, these can also be estimated using maximum likelihood (ML), according to [66], who described it as “the second option for the ordinal variable in which the parcel is being analyzed.” A parcel is a total score across a set of homogeneous items, each with a Likert-type scale. Parcels are generally treated as continuous variables, and their score reliability tends to be for the collective, rather than for individual, items. If the distribution of all parcels is normal, then the default ML estimate could be used to analyze the data.

- Sample size: This study analyzed data with CFA in a SEM model; the optimal sample size was 20 times the number of variables [66]. With 22 variables, the sample size was 440.

- Participants: The respondents were service users who ordered food online through the apps. The survey was conducted from January to February 2021 in the six regional economic provinces of Thailand: Central, Northern, Northeastern, Eastern, Western, and Southern. The total sample size was 1320 people, comprising 220 from each region.

- Table 2 shows the frequency and percentage analysis of basic data from all the samples, such as service users ordering online food delivery, task characteristics, and service frequency. The samples of respondents had the following characteristics—gender: 805 females (61%) and 515 males (39%); age: most were 21–30 (556, 42.1%) and 31–40 (358, 27.1%); education: most had a bachelor’s degree (817: 61.9%), followed by high school (299: 22.7%); occupation: most respondents were students (395: 29.9%), followed by company employees (366: 27.7%); income per month: most earned TBH 10,001–20,000 (413: 31.3%), followed by TBH 5000–10,000 (266: 20.2%). The highest frequency of online food ordering was less than 4 times a month (683: 51.7%), followed by 5–10 times per month (405: 30.7%)

Table 2. Characteristics of the sample.

Table 2. Characteristics of the sample.

3.2. Reliability

To validate the quality of the research tool, five specialists validated the content and determined the consistency of each question by analyzing and scoring the questions against item-objective congruence (IOC). An IOC index above 0.5 meant that the validity of the inquiries was within the acceptable range. A pilot study was subsequently conducted with 30 respondents, not included in this research, using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to analyze the reliability of the questionnaire. The details indicated an alpha value of 0.784–0.965, and these values were higher than the suggested value of 0.7 [67].

3.3. Structural Equation Modeling

SEM is a statistical method that measures the relationship between observed and latent or unobserved variables, or the relationship between two or more latent variables. The important characteristic of SEM is that it is a linear equation. In addition, finding the relationship between variables can uncover causal variables. The interaction between variables or between variable groups occurs simultaneously.

SEM comprises a measurement and a structural model. The measurement model builds candidates, including measured variables and sub-variables, and indicates whether or not the candidate is a good one. In this model, the variable coefficients are called factor loadings. The structural model is the causal model consisting of independent and dependent variables, together with latent variables. It indicates whether the independent variable caused the dependent variable or not. In this model, the variable coefficients are called regression weight and factor loadings. The details of SEM were included in the study by the authors of [66,68].

Therefore, SEM was the method used to build a structural model to determine the relationship between the attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral control that affect consumer behavior toward online food ordering. Each measurement model was analyzed to determine which factors had the greatest loading for use in further policy recommendations.

4. Findings

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The analyses of mean, standard deviation, and R-squared values of the basic data from 1320 samples are shown as in Table 3.

4.2. Structural Equation Model

4.2.1. Goodness-of-Fit Statistics

The results showed that the model was quite consistent with the empirical data: χ2 = 551.898; df = 189; p < 0.000; χ2/df = 2.920; RMSEA = 0.038; CFI = 0.984; TLI = 0.981; and SRMR = 0.034. When comparing the appropriate criteria, it was recommended that χ2/df be 2–5 [69]; (2) RMSEA less than 0.07 [70]; CFI equal to or greater than 0.90 [71]; (4) TLI equal to or greater than 0.80 [72]; and SRMR equal to or less than 0.70 [71].

4.2.2. Measurement Model

The statistical values were based on empirical data comprising 8 latent variables and 22 indicators. Considering the standardized loading values, they were in the range of 0.739–0.922, whereas the threshold should be greater than 0.4. Thus, the model was a statistically significant method (p < 0.001), and the standard loading values for each item are as follows:

Based on the relative weighting assessment of BI from the three observed variables (I1–3), I3 showed a maximum loading score of 0.894, followed by I1 with 0.890. Of the three observed variables, attitudes toward FDAs (I4–6), I5 and I6 had an equal loading score of 0.761, followed by I4 with 0.740. Of the two subjective norm variants, I7 had the higher loading score of 0.853, whereas I8 had 0.742. Of the three PBC variables (I9–11), I10 had the maximum loading score of 0.922, followed by I9 with 0.890. Of the 3 PEOU variables (I12–14), I12 had the highest loading score of 0.883, followed by I13 with 0.878. Of the 3 perceived usefulness variables (I15–17) I17 had the maximum loading score of 0.896, followed by I15 with 0.871. Of the two trust variables (I18–19), I18 had a score of 0.861, followed by I19 with 0.829. Out of three TTF variables (I20–22), I21 had the maximum loading score of 0.886, followed by I22 with 0.863.

From the above data, I10 had the highest loading score of 0.922, followed by I3 with 0.894. The lowest indicator was I11 with 0.739. The results of the measurement model are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

| Construct | Variables | Mean | SD | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Intention [53] | I1: I intend to use the food delivery app. | 3.82 | 0.839 | 0.792 |

| I2: If I have an opportunity, I will order food through the delivery app. | 3.85 | 0.814 | 0.790 | |

| I3: I intend to keep ordering food through the delivery app. | 3.80 | 0.845 | 0.799 | |

| Attitude [53] | I4: Using the food delivery app is useful. | 4.11 | 0.823 | 0.548 |

| I5: I am strongly in favor of ordering food through the delivery app. | 3.69 | 0.927 | 0.579 | |

| I6: I desire to use the delivery app when I purchase food. | 3.77 | 0.870 | 0.579 | |

| Subjective Norms [48] | I7: How do you think your friends would respond if they thought you had used a food delivery application? | 3.72 | 0.803 | 0.728 |

| I8: How do you think your parents would respond if they thought you had used a food delivery application? | 3.50 | 0.917 | 0.550 | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control [73] | I9: In general, ordering food online is very complex. | 3.04 | 1.033 | 0.793 |

| I10: With ordering food online via application creates anxiety for you. | 2.94 | 1.083 | 0.850 | |

| I11: In general, ordering food online yields (will yield) few problems for me. | 3.10 | 1.048 | 0.546 | |

| Perceived Ease of Use [48] | I12: I would find it easy to order food using a food delivery application. | 3.93 | 0.784 | 0.779 |

| I13: My operation of a food delivery application would be clear and understandable. | 3.91 | 0.788 | 0.770 | |

| I14: Using a food delivery application would not require a lot of mental effort. | 3.84 | 0.807 | 0.693 | |

| Perceived Usefulness [48] | I15: Using a food delivery application would enable me to better check the ordering and receiving process of delivery food. | 3.93 | 0.797 | 0.758 |

| I16: Using a food delivery application would make it more convenient to order and receive delivery food. | 3.97 | 0.783 | 0.754 | |

| I17: Food delivery application would be useful for ordering and receiving delivery food. | 3.95 | 0.787 | 0.803 | |

| Trust [53] | I18: I trust the food delivery app. | 3.85 | 0.760 | 0.742 |

| I19: The information provided by the food delivery app is reliable. | 3.85 | 0.758 | 0.687 | |

| Task–Technology Fit [41] | I20: The functions of FDAs are enough for me to order and receive the delivery food. | 3.85 | 0.760 | 0.741 |

| I21: The functions of FDAs are appropriate to help manage the ordering and receiving the delivery of food. | 3.87 | 0.780 | 0.784 | |

| I22: The functions of FDAs fully meet my requirements of ordering and receiving the delivery of food. | 3.88 | 0.772 | 0.774 |

4.2.3. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

The composite reliability [66,68] and average variance extracted (AVE) were calculated, respectively, using Equations (1) and (2):

where is the standardized factor loadings obtained by CFA, i is the number of observed variables in each variable factor, and is the error variance terms of measurement models under the condition CR ≥ 0.7 [66,68]. The CR was 0.779–0.920 for TPB analysis with AVE ≥ 0.5 [66,68].

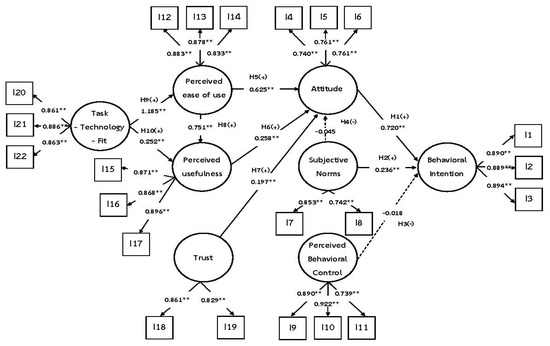

SEM using maximum probability showed that the levels of conformity index were χ2 = 551.898; df = 189; (p < 0.000); χ2/df = 2.920; RMSEA = 0.038; CFI = 0.984; TLI = 0.981; and SRMR = 0.034. The conformity index value indicated that they were sufficient. Thus, it could be concluded that the SEM was based on empirical data. In addition, when examining the 10 hypotheses in Table 4, we found that they influenced behavioral intentions in ordering food online in the following ways:

Table 4.

Measurement model results.

Table 4 presents the SEM results for a structural model that explores the relationship between the three variables influencing the behavioral intention to order food through online apps. The standard regression coefficient (coef.) indicated that the attitude factor had the greatest influence on behavioral intentions (0.720), followed by subjective norms (0.236) and PBC factors (−0.018). The standard regression coefficient (coef.) indicated that the PEOU factor had the greatest influence on attitude (0.625), followed by the perceived benefit factor (0.258), credibility factor (0.197), and subjective norms (−0.045), and that the correlation analysis results between the two exogenous variables influenced the perceived usefulness of ordering food through apps. A coef. indicated that the PEOU had the greatest influence on perceived usefulness (0.751), followed by the TTF factor (0.252). The results regarding the task and technology suitability analysis influencing PEOU in work operations had a coef. of 1.185. The results of factors affecting behavioral intentions to order online food delivery and the analytical results of the hypothesis testing are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Standardized path coefficient and t-value for the structural model.

The conclusion of the investigation based on the proposed research hypotheses (H1–H10) found that the hypotheses had a significant effect on the correlation, as indicated and shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Results of main-test research model. Notes: →result is supported; ⇢result is not supported. ** significant at 0.05 level.

5. Discussion

The key objective of this research was to develop an SEM to examine the structural relationships of online food ordering through food-ordering apps. The factors studied in the TAM theory consist of credibility, PEOU, PU, ATT, and BI. For TPB, the factors included SN and PBC. One additional factor was also explored: TTF and technology characteristics. The study method used a CFA index consisting of 10 hypotheses for structural equation analysis to examine the correlation among the various factors. The CFA assessment results showed that we certified the model components as statistically significant. Moreover, from SEM analysis, we found that the model consistency index was quite consistent with 8 out of 10 hypotheses. The factors were significantly related to the hypotheses as follows:

According to SEM, the factors that directly influenced the intention to order food online through the food-delivery application were ATT, SN, and PBC. While testing the standardized path coefficients, we found that ATT had the greatest influence on BI at 0.720, meaning that shopping attitudes had a direct, positive influence on the BI to use the food-ordering apps. Therefore, if users are satisfied or have a good experience, they will have a positive attitude toward the app and a tendency to use it. Consistent with research by the authors of [19,38,52,54,55,56,57,74], results showed that ATT positively affected BI to order food online, followed by SN influencing a continued intention to use equal to 0.236, meaning that when consumers receive advertisements about online food ordering from subjective norms, such as close friends or parents, they will be interested in ordering food through apps and express their behavior by using them, as found in the studies by the authors of [38,48,57]. The factors that directly influenced ATT toward online food ordering through apps are PEOU, PU, and credibility. While examining standardized path coefficients, we found that PEOU had an influence on ATT toward ordering food through apps equal to 0.625, meaning that when consumers perceive an ease of use, they have a positive attitude toward ordering online food through these apps. In addition, the PU influence on ATT to use food-ordering apps was equal to 0.258, meaning that, when consumers recognize the usefulness of the application for both ordering and receiving food, and checking the details of the food from the app, they have positive attitudes toward online food ordering, which is consistent with the studies by the authors of [28,38,56]. The credibility influence on attitudes toward ordering food through apps had a value of 0.197, meaning that when consumers consider the apps to be trustworthy, they are likely to order food through them, which is consistent with research from the authors of [28,38,52]. The factors directly influencing PU include PEOU and TTF. Examining standardized path coefficients, we found that the value of the PEOU influence on PU was equal to 0.751, meaning that when consumers perceived that apps were easy to use, they perceived food-ordering apps to be highly beneficial, which agrees with research from the authors of [29,38,48].

The TTF factor influenced perceived usefulness at 0.252 and PEOU at 1.185, indicating that that consumers saw the app functions as suitable for either ordering or receiving food. In addition, when consumers encounter problems using the apps, channels should be provided so that consumers can contact someone for help, or solve the problem themselves. If the apps provide solutions, consumers will be more satisfied with the apps, which is in line with the research of the authors of [42,43,75]. In addition, two hypotheses were proven false: PBC influences BI and SN influences ATT. In other words, the analysis of PBC data did not influence BI toward online food ordering and had an effect value of −0.018, demonstrating that consumers are still concerned about ordering food through the apps because they are worried about complicated apps. The analysis result showed that SN did not influence ATT, with an effect value of −0.045. This means that when consumers receive online food-ordering advertisements from subjective norms, such as close friends or parents, they are not interested in using food-ordering apps at all. For example, consumers may have received information from subjective norms that the apps are not practical or that the food is not as specified in the apps. In the short term, we believe that the demand for online food ordering services continues to be popular because consumers want convenience in daily life, but for the long run, entrepreneurs must create a strategy to convince consumers to continue to use the service. This may be conducted using a marketing mix to motivate and retain customers to use the service continuously.

6. Conclusions

The authors used an SEM method due to its compatibility and efficiency for measuring complicated phenomena. Serving a similar purpose to multiple regression, SEM is more efficient for considering the following issues: the interaction model, nonlinearity, correlated independent variables, measurement errors, corresponding error conditions, multiple latent independent variables, and one or more latent dependent variables [66]. The data collected in Thailand was from six regions: Central, North, Eastern, Northeastern, Western, and Southern.

The research results allowed us to rank the exogenous variables by the strength of their influence on BI, which is influenced by ATT. If the consumers have a positive attitude toward using apps, they will have a positive tendency to use FDAs. They may consider or look through them before choosing to use one, particularly, if they have a positive attitude toward PEOU, PU, and credibility.

Since consumers want to order food conveniently through the apps, the entrepreneurs should establish promotions to attract consumers and use the app attributes as a medium. This procedure allows immediate communication between apps and consumers, such as obtaining product information for decision making about using the service and facilitating processes such as payment and food delivery. In addition, if consumers find that apps are suitable, either for ordering or receiving food, consumers will decide to use them. Moreover, subjective norms, such as friends, close friends, and parents, will affect consideration before ordering via the apps or making an immediate purchase decision. Consumers who order food or buy goods through online apps do not choose them without seeing the actual products. If an incentive stimulates their demand, sharing information or advertising products through social norms about offering the food to consumers may build consumer attention, or if they depend on these groups, an immediate purchase decision may be possible. The analysis results showed that PBC did not influence behavioral intentions toward online food ordering. The reason is that some consumers still have anxiety about ordering food through complicated apps. Thus, if a business owner develops a practical food-ordering app, the consumers will increasingly use it to order food. Moreover, most consumers tend to order food via apps. Therefore, governmental or other relevant agencies should adopt these research results to formulate policies that facilitate the purchase of goods in the digital marketing system.

The results found that the attitude factor (H1) affected consumers’ online food-ordering behavior the most, followed by subjective norms (H2). Responding to the needs of users will affect the frequency of use. It was also found that the ease-of-use factor (H5) affected the attitude toward app use the most, followed by perceived usefulness (H6) and trust (H7), respectively. The next factor, perceived ease of use, affected perceived usefulness (H8). Therefore, if the platform is easy to use, it will enhance the users’ positive attitudes, resulting in repeated use and referrals to others. In addition, this research included additional studies in the task–technology fit section; the study’s results revealed that TTF had the most significant impact on perceived ease of use (H9), followed by perceived usefulness (H10). This meant that if a food-ordering platform is appropriate for use, consumers will continue to use it, leading to sustainable business operations. According to the research, this was consistent with the SDGs: responsible consumption and production. It will allow consumers to use more services, thereby improving profits and employment. Most importantly, it will help businesses achieve sustainability. This is in line with the research by the authors of [76], which studied the behavior of consumers in the early stages of drone food delivery and found that there was not much use for the service.

7. Limitations and Future Work

This study highlighted the guidelines for studying users’ behavioral intention to use food-delivery services via online apps. However, there were some limitations. There was a slight difference in the question items used in our research because we used questions from various researchers who studied food ordering online to determine behavioral intention. Future research should study theories beyond just TAM and TPB to obtain more diverse attitudes of the service users. Another limitation was the scope of the study. As the results were acquired from questioning only online food-delivery users via apps in the provinces representing each region, the results or levels of significance may vary in other countries. Future studies should examine attitudes toward a wide variety of apps using other theories that affect user behavior to understand users’ opinions on FDAs.

Author Contributions

C.I.: conceptualization, methodology, software, and writing—original draft; T.C.: software, validation, and formal analysis; S.J.: data curation; V.C.: writing—review and editing; V.R.: supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by (i) Suranaree University of Technology (SUT), (ii) Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI), and (iii) the National Science Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) (Grant number: RU-7-706-59-03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee, Suranaree University of Technology (COE No. 81/2563).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Internet World Stats. Internet User Distribution in the World-2021. Available online: https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Martínez-Domínguez, M.; Mora-Rivera, J. Internet adoption and usage patterns in rural Mexico. Technol. Soc. 2020, 60, 101226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schehl, B.; Leukel, J.; Sugumaran, V. Understanding differentiated internet use in older adults: A study of informational, social, and instrumental online activities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkijika, S.F. Factors influencing the adoption of mobile commerce applications in Cameroon. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Intelligence Center Thailand Food Market Report 2019. Available online: http://fic.nfi.or.th/MarketOverviewDomesticDetail.php?id=269 (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Kasikorn Research Center. After COVID-19 Food Delivery Business Expands on Fierce Compettition. Available online: https://www.kasikornresearch.com/th/analysis/k-econ/business/Pages/z3128-Food-Delivery.aspx (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Bank of Thailand. The Crisis of COVID-19 and Business Trends Shipping under Next Normal. Available online: https://www.bot.or.th/Thai/ResearchAndPublications/articles/Pages/Article_14Apr2020.aspx (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Economic Intelligence Center. Inside Food Delivery Business: Moving Forward to Expand the Market with a Variety of Services. Available online: https://www.scbeic.com/th/detail/file/product/7906/g3uws6soy7/EIC_Note_Food-delivery_20211102.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Hwang, J.; Kim, H. Consequences of a green image of drone food delivery services: The moderating role of gender and age. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 872–88410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, Y.-S. Channel integration affects usage intention in food delivery platform services: The mediating effect of perceived value. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J. Perceived risks from drone food delivery services before and after COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. 2021, 33, 1276–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.T. Factors affecting online food delivery service in Bangladesh: An empirical study. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Cho, S.-B.; Kim, W. Consequences of psychological benefits of using eco-friendly services in the context of drone food delivery services. J. Travel Tour. Mark 2019, 36, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.A. Mobile food ordering apps: An empirical study of the factors affecting customer e-satisfaction and continued intention to reuse. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annaraud, K.; Berezina, K. Predicting satisfaction and intentions to use online food delivery: What really makes a difference? J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2020, 23, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, N.; Gupta, S.; Nanda, N. Food delivery services and customer preference: A comparative analysis. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2019, 22, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, P.; Tarafder, T.; Pearson, D.; Henryks, J. Intention-behaviour gap and perceived behavioural control-behaviour gap in theory of planned behaviour: Moderating roles of communication, satisfaction and trust in organic food consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 81, 103838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Dhir, A.; Ray, A.; Bala, P.K.; Khalil, A. Innovation resistance theory perspective on the use of food delivery applications. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2020, 34, 1746–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, W. Investigating motivated consumer innovativeness in the context of drone food delivery services. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 38, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, U.; Ansari, A.R.; Fu, G.; Junaid, M. Feeling hungry? let’s order through mobile! examining the fast food mobile commerce in China. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, C.; Cegrell, O.; Vesterinen, J. Digitally enabling sustainable food shopping: App glitches, practice conflicts, and digital failure. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, J.C.; Garzón, W.; Brooker, P.; Sakarkar, G.; Carranza, S.A.; Yunado, L.; Rincón, A. Evaluation of collaborative consumption of food delivery services through web mining techniques. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2019, 46, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, W.; Kim, J.J. Application of the value-belief-norm model to environmentally friendly drone food delivery services: The moderating role of product involvement. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. 2020, 32, 1775–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Jain, A.; Hsieh, J.-K. Impact of apps aesthetics on revisit intentions of food delivery apps: The mediating role of pleasure and arousal. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirsehan, T.; Cankat, E. Role of mobile food-ordering applications in developing restaurants’ brand satisfaction and loyalty in the pandemic period. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangmee, C.; Kot, S.; Meekaewkunchorn, N.; Kassakorn, N.; Khalid, B. Factors determining the behavioral intention of using food delivery apps during COVID-19 pandemics. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res 2021, 16, 1297–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Shah, A. Revisiting food delivery apps during COVID-19 pandemic? Investigating the role of emotions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Ruan, W.J.; Jeon, Y.J.J. An integrated approach to the purchase decision making process of food-delivery apps: Focusing on the TAM and AIDA models. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2021, 95, 102943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-Y.; Lee, S.-B.; Jeon, Y.J.J. Factors influencing the behavioral intention to use food delivery apps. Soc. Behav. Pers. Inter. J. 2017, 45, 1461–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Kaur, P.; Bhatt, Y.; Mäntymäki, M.; Dhir, A. Why do people purchase from food delivery apps? A consumer value perspective. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T. Understanding Chinese consumer adoption of apparel mobile commerce: An extended TAM approach. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasilingam, D.L. Understanding the attitude and intention to use smartphone chatbots for shopping. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajak, M.; Shaw, K. An extension of technology acceptance model for mHealth user adoption. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.; Kwok, R.C.-W.; Ng, M. An extended online purchase intention model for middle-aged online users. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2016, 20, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystrand, B.T.; Olsen, S.O. Consumers’ attitudes and intentions toward consuming functional foods in Norway. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 80, 103827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Cavallo, C.; Caso, D.; Del Giudice, T.; De Devitiis, B.; Viscecchia, R.; Nardone, G.; Cicia, G. Explaining consumer purchase behavior for organic milk: Including trust and green self-identity within the theory of planned behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 76, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troise, C.; O’Driscoll, A.; Tani, M.; Prisco, A. Online food delivery services and behavioural intention–a test of an integrated TAM and TPB framework. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 664–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, C.; Bradley, L.; Prentice, G.; Verner, E.-J.; Loane, S. Gender differences using online auctions within a generation Y sample: An application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhuillier, A. The Moderating Role of Social Distancing in Mobile Commerce Adoption. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2022, 52, 101116. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Bacao, F. What factors determining customer continuingly using food delivery apps during 2019 novel coronavirus pandemic period? Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2020, 91, 102683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, G.; Schramm-Klein, H.; Steinmann, S. Consumers’ attitudes and intentions toward Internet-enabled TV shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.-H. Extending a TAM–TTF model with perceptions toward telematics adoption. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist 2019, 31, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Marjerison, R.K.; Choi, J.; Chae, C. Supply Chain Sustainability during COVID-19: Last Mile Food Delivery in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippini, F. Sustainability in the Last Mile Online Food Delivery: An Important Contribution Using the Case Study of “Glovo”. 2021. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2445/179738 (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Kasikorn Research Center. Food Delivery Application to Drive Food Delivery Business to Continue to Grow. Available online: https://kasikornresearch.com/SiteCollectionDocuments/analysis/k-social-media/sme/food%20Delivery/FoodDelivery.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Ray, A.; Dhir, A.; Bala, P.K.; Kaur, P. Why do people use food delivery apps (FDA)? A uses and gratification theory perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, M.; Park, K. Adoption of O2O food delivery services in South Korea: The moderating role of moral obligation in meal preparation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 262–27349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-T.; Ou, W.-M.; Chen, W.-Y. The impact of inertia and user satisfaction on the continuance intentions to use mobile communication applications: A mobile service quality perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. In Englewood Cliffs; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.-W.; Namkung, Y. The information quality and source credibility matter in customers’ evaluation toward food O2O commerce. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2019, 78, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Bonn, M.A.; Li, J.J. Differences in perceptions about food delivery apps between single-person and multi-person households. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2019, 77, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amin, M.; Arefin, M.S.; Alam, M.R.; Ahammad, T.; Hoque, M.R. Using mobile food delivery applications during COVID-19 pandemic: An extended model of planned behavior. J. Food Prod. Mark 2021, 27, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.Y.; Choi, Y.G.; Kim, J.J. A comparative study on the motivated consumer innovativeness of drone food delivery services before and after the outbreak of COVID-19. J. Food Prod. Mark 2021, 38, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gârdan, D.A.; Epuran, G.; Paștiu, C.A.; Gârdan, I.P.; Jiroveanu, D.C.; Tecău, A.S.; Prihoancă, D.M. Enhancing Consumer Experience through Development of Implicit Attitudes Using Food Delivery Applications. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2858–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J. Merging the norm activation model and the theory of planned behavior in the context of drone food delivery services: Does the level of product knowledge really matter? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag 2020, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Tourism, technology and ICT: A critical review of affordances and concessions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems: Theory and Results; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodhue, D.L.; Thompson, R.L. Task-technology fit and individual performance. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, S.; Khan, M.M.; Alghizzawi, M. Extension of technology continuance theory (TCT) with task technology fit (TTF) in the context of Internet banking user continuance intention. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. 2020, 38, 986–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-M. Understanding cloud ERP continuance intention and individual performance: A TTF-driven perspective. Benchmarking Int. J. 2020, 27, 1591–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About SDGs. Available online: https://opendata.nesdc.go.th/sdg-page (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Confirmatory Factor Analysis, Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 600–638. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hocevar, D. Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First-and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups’. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 97, 562–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J.H. Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu Lt Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struc. Equa. Model. Multi. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Evaluating Model Fit: A Synthesis of the Structural Equation Modelling Literature. In Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, Regent’s College, London, UK, 19–20 June 2008; pp. 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, T. Consumer values, the theory of planned behaviour and online grocery shopping. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo VC, S.; Goh, S.-K.; Rezaei, S. Consumer experiences, attitude and behavioral intention toward online food delivery (OFD) services. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 150–162. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Chen, X. Continuance intention to use MOOCs: Integrating the technology acceptance model (TAM) and task technology fit (TTF) model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 67, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, N.I.; Kasim, H.; Mahmoud, M.A. Towards the Development of Smart and Sustainable Transportation System for Foodservice Industry: Modelling Factors Influencing Customer’s Intention to Adopt Drone Food Delivery (DFD) Services. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).