Couple Ethical Purchase Behavior and Joint Decision Making: Understanding the Interaction Process and the Dynamics of Influence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ethical Consumers and Their Ethical Purchase Decisions

2.2. Couple Decision Making as an Interaction Process

2.3. Dynamics of Influence within Family in Relation to Ethical Consumption

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Couples’ Decisions and Ethical Purchasing

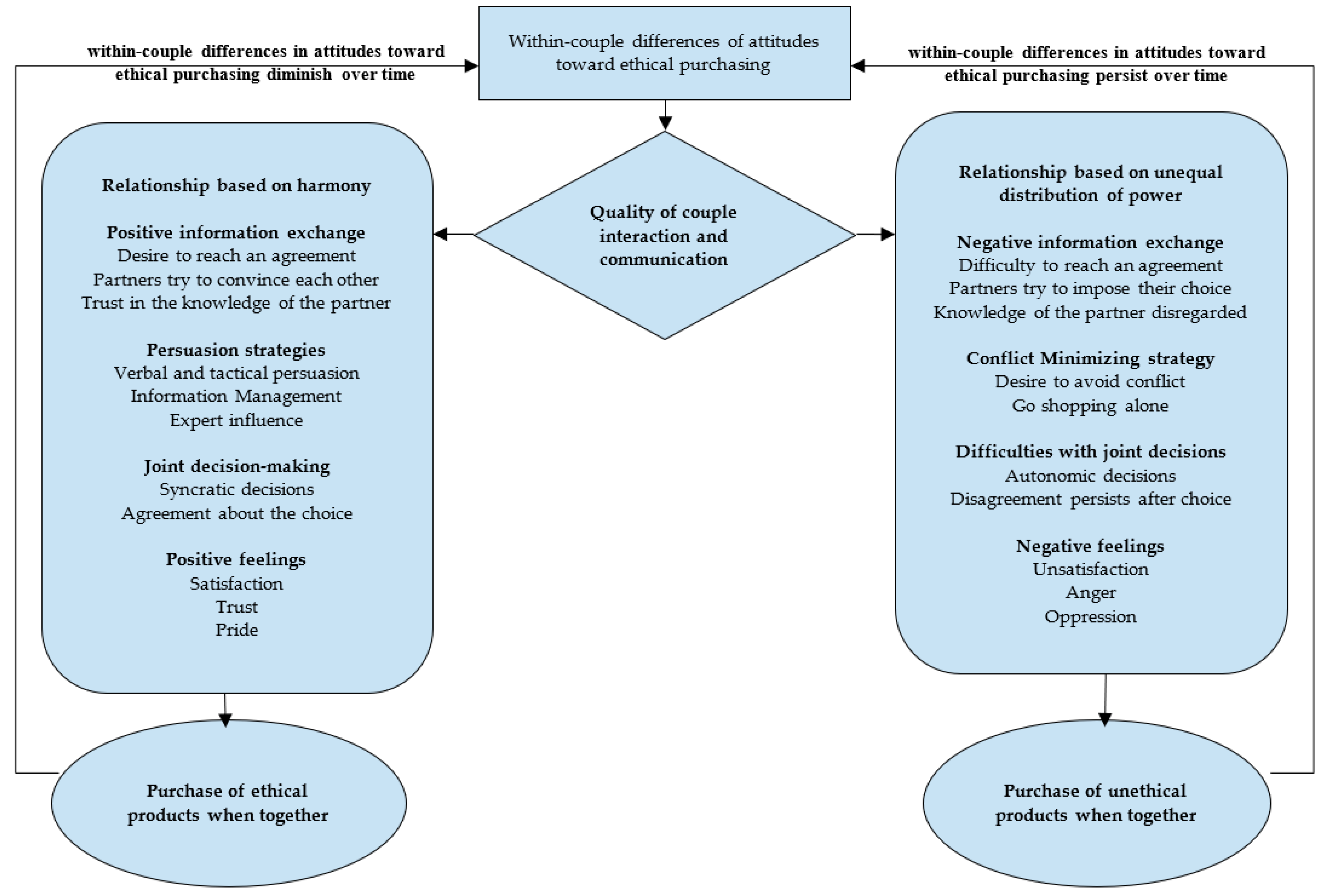

4.1.1. Interactions and Decision Making within Ethical Couples

4.1.2. Interactions and Decision Making within Unethical Couples

4.2. Factors Restricting Couple Ethical Purchasing

4.2.1. Time Restriction

4.2.2. Money Restriction

4.2.3. Pleasure Restriction

4.3. Couple Intention of Behavioral Change towards More Ethical Purchasing

4.3.1. Desire to Change Couple’s Attitude towards Ethical Purchasing

4.3.2. Easier to Convince the Other Regarding Food

4.3.3. Perceived Importance of Couple Life-Cycle Transitional Events

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheung, M.F.; To, W.M. The effect of consumer perceptions of the ethics of retailers on purchase behavior and word-of-mouth: The moderating role of ethical beliefs. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 771–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.P. Consumers’ purchase behaviour and green marketing: A synthesis, review and agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1217–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akenji, L.; Bengtsson, M. Making sustainable consumption and production the core of sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2014, 6, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bigliardi, B.; Filippelli, S. Investigating circular business model innovation through keywords analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur-Wierzbicka, E. Circular economy: Advancement of European Union countries. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M.; Alfredsson, E.; Cohen, M.; Lorek, S.; Schroeder, P. Transforming systems of consumption and production for achieving the sustainable development goals: Moving beyond efficiency. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1533–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. Inside the sustainable consumption theoretical toolbox: Critical concepts for sustainability, consumption, and marketing. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 78, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesini, G.; Castiglioni, C.; Lozza, E. New trends and patterns in sustainable consumption: A systematic review and research agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.; Johns, N.; Kilburn, D. An exploratory study into the factors impeding ethical consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carrigan, M.; Szmigin, I.; Wright, J. Shopping for a better world? An interpretive study of the potential for ethical consumption within the older market. J. Cons. Mark. 2004, 21, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, K.M.; Velazquez, L.; Munguia, N. Reflections on sustainable consumption in the context of COVID-19. Front. Sustain. 2021, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, S.; Hickmann, T.; Lederer, M.; Marquardt, J.; Schwindenhammer, S. The 2030 agenda for sustainable development: Transformative change through the sustainable development goals? Politics Gov. 2021, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toti, J.F.; Moulins, J.L. Comment mesurer les comportements de consommation éthique? Rev. Int. Manag. Homme Entrep. 2015, 4, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Lobo, A.; Greenland, S. Energy efficient household appliances in emerging markets: The influence of consumers’ values and knowledge on their attitudes and purchase behavior. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwah, S.; Dhir, A.; Sagar, M.; Gupta, B. Determinants of organic food consumption. A systematic literature review on motives and barriers. Appetite 2019, 143, 104402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Lee, J. The effects of consumers’ perceived values on intention to purchase upcycled products. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønhøj, A. Communication about consumption: A family process perspective on ‘green’ consumer practices. J. Consum. Behav. 2006, 5, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, L.; Shaw, D.; Shiu, E. The impact of ethical concerns on family consumer decision-making. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, N.R.; Zoellick, J.C.; Deutschbein, J.; Anton, V.; Bergmann, M.M.; Schenk, L. Dietary preferences in the context of intra-couple dynamics: Relationship types within the German NutriAct family cohort. Appetite 2021, 167, 105625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellaoui, M.; L’Haridon, O.; Paraschiv, C. Individual vs. collective behavior: An experimental investigation of risk preferences. Theory Decis. 2013, 75, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellaoui, M.; L’Haridon, O.; Paraschiv, C. Do Couples Discount Future Consequences Less than Individuals? Available online: https://crem-doc.univ-rennes1.fr/wp/2013/201320.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Garbinsky, E.N.; Gladstone, J.J.; Nikolova, H.; Olson, J.G. Love, lies, and money: Financial infidelity in romantic relationships. J. Cons. Res. 2020, 47, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A.F.; Lynch, J.G. On a need-to-know basis: How the distribution of responsibility between couples shapes financial literacy and financial outcomes. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 45, 1013–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glogovețan, A.I.; Dabija, D.C.; Fiore, M.; Pocol, C.B. Consumer perception and understanding of European Union quality schemes: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Andronie, M.; Uţă, C.; Hurloiu, I. Trust management in organic agriculture: Sustainable consumption behavior, environmentally conscious purchase intention, and healthy food choices. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, W.; Davenport, E. Has the medium (roast) become the message? The ethics of marketing fair trade in the mainstream. Int. Mark. Rev. 2005, 22, 494–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, P.; Devinney, T.M. Do what consumers say matter? The misalignment of preferences with unconstrained ethical intentions. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulstridge, E.; Carrigan, M. Do consumers really care about corporate responsibility? Highlighting the attitude—behavior gap. J. Commun. Manag. 2000, 4, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Longo, C.; Shankar, A.; Nuttall, P. It’s not easy living a sustainable lifestyle: How greater knowledge leads to dilemmas, tensions and paralysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 759–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, N.; Paraschiv, C.; Rousset, X. Online dynamic pricing and consumer-perceived ethicality: Synthesis and future research. Rech. App. Mark. 2017, 32, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Driesen, L.; Rayp, G. Do consumers care about ethics? Willingness to pay for fair-trade coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 363–385. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23860612 (accessed on 23 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Schäufele, I.; Janssen, M. How and why does the attitude-behavior gap differ between product categories of sustainable food? Analysis of organic food purchases based on household panel data. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 595636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhir, A.; Sadiq, M.; Talwar, S.; Sakashita, M.; Kaur, P. Why do retail consumers buy green apparel? A knowledge-attitude-behaviour-context perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Attalla, A. The myth of the ethical consumer–do ethics matter in purchase behavior? J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Velicer, W.F.; DiClemente, C.C.; Prochaska, J.O.; Brandenburg, N. Decisional balance measure for assessing and predicting smoking status. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freestone, O.M.; McGoldrick, P.J. Ethical positioning and political marketing: The ethical awareness and concerns of UK voters. J. Mark. Manag. 2007, 23, 651–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleim, M.; Lawson, J.S. Spanning the gap: An examination of the factors leading to the green gap. J. Consum. Mark. 2014, 31, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.C.; Yoon, S.J. Theory-based approach to factors affecting ethical consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, H.M.; Lourenço, T.F.; Silva, G.M. Green buying behavior and the theory of consumption values: A fuzzy-set approach. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1484–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Karakas, F.; Sarigöllü, E. Exploring pro-environmental behaviors of consumers: An analysis of contextual factors, attitude, and behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3971–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tran, A.T.V.; Nguyen, N.T. Organic food consumption among households in Hanoi: Importance of situational factors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; Anandya, D. Exploring the impact of empathy, compassion, and Machiavellianism on consumer ethics in an emerging market. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; Septianto, F.; Chowdhury, R.M. Religious but not ethical: The effects of extrinsic religiosity, ethnocentrism and self-righteousness on consumers’ ethical judgments. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.; Wong, Y.H.; Leung, T.K. Applying ethical concepts to the study of green consumer behavior: An analysis of Chinese consumers’ intentions to bring their own shopping bags. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 79, 469–481. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25482129 (accessed on 23 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Kirchler, E.; Winter, L.; Penz, E. Methods of studying economic decisions in private households. Rev. Crítica Ciências Sociais 2016, 111, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Britt, S.L.; Hill, E.J.; Lebaron, A.; Lawson, D.R.; Bean, R.A. Tightwads and spenders: Predicting financial conflict in couple relationships. J. Financ. Plan. 2017, 30, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler, E. Spouses’ joint purchase decisions: Determinants of influence tactics for muddling through the process. J. Econ. Psychol. 1993, 14, 405–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corfman, K.P.; Lehmann, D.R. Models of cooperative group decision-making and relative influence: An experimental investigation of family purchase decisions. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 1–13. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2489238 (accessed on 23 June 2022). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kirchler, E. Conflict and Decision-Making in Close Relationships: Love, Money, and Daily Routines; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Benmoyal-Bouzaglo, S.; Paraschiv, C. Quand Amour et Argent doivent rimer au quotidien… Un agenda de recherche sur la gestion des finances au sein des couples. Gerer Compr. 2021, 143, 13–24. Available online: https://www.annales.org/gc/2021/gc143/2021-03-02.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Brandstätter, H. Gruppenleistung und Gruppenentscheidung. In Sozialpsychologie. Ein Handbuch in Schlüsselbegriffen; Frey, D., Greif, S., Eds.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1987; pp. 182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Spiro, R.L. Persuasion in family decision-making. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 9, 393–402. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2488789 (accessed on 23 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Kliestik, T.; Zvarikova, K.; Lăzăroiu, G. Data-driven machine learning and neural network algorithms in the retailing environment: Consumer engagement, experience, and purchase behaviors. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 2022, 17, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, E. Machine learning tools, algorithms, and techniques in retail business operations: Consumer perceptions, expectations, and habits. J. Self-Gov. Manag. Econ. 2022, 10, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, M.L.; Hooper, S. Social influence and green consumption behaviour: A need for greater government involvement. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 827–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterling, D.; Miller, S.; Weinberger, N. Environmental consumerism: A process of children’s socialization and families’ resocialization. Psychol. Mark. 1995, 12, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schill, M.; Godefroit-Winkel, D.; Hogg, M.K. Young children’s consumer agency: The case of French children and recycling. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotte, J.; Wood, S.L. Families and innovative consumer behavior: A triadic analysis of sibling and parental influence. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Alony, I. Guiding the use of Grounded Theory in doctoral studies–An example from the Australian film industry. Int. J. Doct. Stud. 2011, 6, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, B.; Cardon, P.; Poddar, A.; Fontenot, R. Does sample size matter in qualitative research?: A review of qualitative interviews in IS research. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2013, 54, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, E.; Paraschiv, C. Le coaching, un vecteur de changement au sein des organisations? Rev. Française De Gest. 2020, 46, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qual. Res. 2008, 8, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; SAGE: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, H. An exploratory study of how latecomers transform strategic path in catch-up cycle. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isensee, C.; Teuteberg, F.; Griese, K.M. Exploring the use of mobile apps for fostering sustainability-oriented corporate culture: A qualitative analysis. Sustainability 2022, 1, 7380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunk, K.H. Exploring origins of ethical company/brand perceptions: Reply to Shea and Cohn’s commentaries. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 12, 1364–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czellar, S. Self-presentational effects in the Implicit Association Test. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumard, P.; Donada, C.; Ibert, J.; Xuereb, J.M. La collecte des données et la gestion de leurs sources. Methodes De Rech. En Manag. 1999, 261–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Pölkki, T.; Utriainen, K.; Kyngäs, H. Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 2158244014522633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.L. Decision making within the household. J. Consum. Res. 1976, 2, 241–260. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2488655 (accessed on 23 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.F.; Blackwell, R.D.; Miniard, P.W. Consumer Behavior, 8th ed.; Dryden Press: Forth Worth, TX, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, J.G. The exchange process in close relationships. In The Justice Motive in Social Behavior; Lerner, M.J., Lerner, S.C., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1981; pp. 261–284. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, R. Altruistic or egoistic: Which value promotes organic food consumption among young consumers? A study in the context of a developing nation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 33, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, N.; Paraschiv, C.; Vernette, É. Vers un référentiel théorique interdisciplinaire du bien-être individuel. Rev. Française De Gest. 2019, 281, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganglmair-Wooliscroft, A.; Wooliscroft, B. Well-being and everyday ethical consumption. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ethical Couples | Unethical Couples | |

|---|---|---|

| Decision Making Process | Joint decision making The partners “decide together” (6) The partners “do the shopping together” (5) The partners “discuss” product choices together before purchasing (4) | Independent decision making The partners “do not discuss much/at all“ (5) One of the partners “decides alone” (4) The partners “rarely do the shopping together” (3) In the store, the less ethical partner “takes what he/she wants” without concertation (3) |

| Information Exchange Process | Positive exchange of information The more ethical partner “tries to convince” the other through discussions (7) Divergent opinions are not seen as a problem (3) The more ethical partner “pushed” toward more ethical purchasing over time (3) Both partners “try to convince” each other (2) | Negative or no exchange of information The less ethical partner “does not care” about ethical purchasing (5) The less ethical partner “refuses the dialogue” (4) The less ethical partner “does not pay attention” in the store (2) The partners are both “not concerned” about ethical purchasing (2) |

| Interaction Strategies | Agreement The more ethical partner “succeeds in convincing” the other (6) The less ethical partner “accepts” the decision of the partner (4) The less ethical partner generally “tends to follow” (3) Persuasion Strategy The more ethical partner “provides information” (5) The more ethical partner actively “searches information” about ethical products (5) The more ethical partner “shows videos” (3) The more ethical partner “makes tasting products” (3) Trust-based interaction The less ethical partner has “trust” in the knowledge of the partner (4) The less ethical partner “thinks the choice of the partner is the best” (2) | Conflict The less ethical partner “does not agree” to ethical purchasing (4) The less ethical partner “ignores ethical information” provided by the partner (4) Conflict-minimizing Strategy The more ethical partner “tries to avoid disputes” by letting go (3) The more ethical partner “doesn’t want to fight at the store” (2) The more ethical partner “makes concessions” (3) The more ethical partner “makes efforts” (2) Power-based interaction The less ethical partner has more “decision power” (3) The more ethical partner “does not really have a choice” (2) |

| Associated Feelings | Positive Feelings The less ethical partner “is proud” of partner’s investment in ethical purchasing (2) | Negative Feelings Partners “get angry” (3) The more ethical partner “feels stuck” (2) |

| Type of Restriction | Associated Aspects |

|---|---|

| Time Restrictions | Purchasing ethical products “takes more time” (8) Decision making process of ethical product “is more complex (rational/analytical) and takes more time” (5) Purchasing ethical products implies more time for “searching information” (5) Purchasing ethical products implies more time for “comparing packaging” (4) Purchasing ethical products implies more time “to go shopping” (3) Purchasing ethical products implies more time “to discuss” the choice and share information before the purchase (3) |

| Money Restrictions | Ethical products have a “higher price” (7) Existence of a “trade-off” between the financial side and the ecological side (5) Ethical products are less expensive if a “long-term perspective” is adopted (5) Ethical products are less expensive if “health effects” are considered (3) Increasing ethical purchasing by “buying less” to reduce the price (3) |

| Pleasure Restrictions | Pleasure is “less ethical” (6) Pleasure “justifies the purchase of unethical products” by the couple (5) Pleasure “justifies a different attitude of the partner” towards ethical purchasing (3) Pleasure increases unethical purchasing by “habit decisions” (3) Pleasure increases unethical purchasing by “impulse buying” (2) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rabeson, L.; Paraschiv, C.; Bertrandias, L.; Chenavaz, R. Couple Ethical Purchase Behavior and Joint Decision Making: Understanding the Interaction Process and the Dynamics of Influence. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138105

Rabeson L, Paraschiv C, Bertrandias L, Chenavaz R. Couple Ethical Purchase Behavior and Joint Decision Making: Understanding the Interaction Process and the Dynamics of Influence. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):8105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138105

Chicago/Turabian StyleRabeson, Landisoa, Corina Paraschiv, Laurent Bertrandias, and Régis Chenavaz. 2022. "Couple Ethical Purchase Behavior and Joint Decision Making: Understanding the Interaction Process and the Dynamics of Influence" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 8105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138105

APA StyleRabeson, L., Paraschiv, C., Bertrandias, L., & Chenavaz, R. (2022). Couple Ethical Purchase Behavior and Joint Decision Making: Understanding the Interaction Process and the Dynamics of Influence. Sustainability, 14(13), 8105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138105