Abstract

In this study, we aimed to explore whether, regardless of the reasons why entrepreneurs start their activity, either due to necessity or vocation, they positively value the capacity of business incubators as a mechanism to help create value, contributing to the economic and social sustainability and establishing a context that increases the chances of the success and survival of businesses. A questionnaire was developed and distributed to a representative sample of entrepreneurs residing in Spain. Structural equation analysis (SEM) was applied. The results confirm that business incubators create value in society regardless of the reasons why entrepreneurs start their activity. This work provides an opinion and a direct vision of how different entrepreneur profiles value the contribution of business incubators to the sustainability of businesses in their first stage.

1. Introduction

According to Cantillón [1], entrepreneurs ensure markets develop correctly. Hence, in-depth study of this profile and the creation of adequate ecosystems to promote this role are necessary. Similarly, business incubators are critical elements for developing and sustaining an efficient entrepreneurial ecosystem [2,3,4,5,6]. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to explore how entrepreneurs value the different socio-economic benefits of business incubators for different reasons.

According to the administrator of the Business Incubator of the “Cámara de Comercio de Santiago de Compostela”, which occupies first place in the business pre-incubation and third place in the ranking of business incubators in Spain according to the Funcas 2019–2020 ranking, business incubators are not places of accommodation (space) or centers for processing administrative issues. Instead, they provide support to entrepreneurs throughout the process, from the moment they enter the incubator until they leave it, helping them to create business ideas; select the most suitable one; carry out paperwork and administrative procedures; and train, mentor, and search for financing through all possible routes [4,7]. In a previous investigation, the functionalities of business incubators were analyzed according to their different socio-economic benefits [2].

The primary purpose of incubators is to explore the most appropriate framework for the creation, development, and maturity of business experiences in each area, establishing a context that increases the chances of the success and survival of businesses [4,7]. They positively influence the ecosystem of an entrepreneur and create value in society [4,8]. Therefore, business incubators participate in the ecosystem by providing quality knowledge-intensive business services and generating good practices in this provisioning process [9].

According to numbers from the National Institute of Statistics (INE) [10], the value of the Spanish entrepreneurial ecosystem increased five-fold in 2015–2021, from 10,000 million to 46,000 million euros [10,11]. In March 2022, 11,071 companies were created, 0.6% more than the same month of 2021 and 1834 more than February 2022 (monthly variation of 19.9%) [10]. The study carried out by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor report (GEM) 2020–2021 [12] on entrepreneurship concludes that, for the creation of companies and their survival to continue to rise, it is important to know the aspects that led to their success and the aspects that have changed after the pandemic, such as the profile of entrepreneurs or new models of business. Before the pandemic, the profile of entrepreneurs was different from the current one. People who decided to start a business were young, aged between 24 and 35 years, with university education, and had few responsibilities, (entrepreneurs by vocation) [12]. However, with the arrival of the pandemic and all the changes that it has brought about, the age of entrepreneurs has increased: the current average age is 42 years [12], which is motivated by the need to seek alternatives due to the scarcity of employment (entrepreneurs out of necessity) [10,11,12]. Moreover, another relevant aspect related to the evolution of entrepreneurship in recent years in Spain is that the government of Spain, within the reforms of the “Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan”, approved the draft of the “Create and Grow Act” [13], which is expected to be applicable throughout this year. Its main characteristic is the reduction in the minimum share capital required to create a company, from 3000 euros to 1 euro. Likewise, it will be possible to set up a company online through the “Information Centre and Business Creation Network” (CIRCE), reducing the terms for its creation and facilitating and reducing the notary and registry costs for the creation of new companies. In addition, the government of Spain has given the green light for the “Startups Act” [13]. It is expected that its parliamentary process will be completed before the end of the year. This project expands tax deductions for entrepreneurs and provides facilities to digital nomads, among other measures, with the aim of “attracting talent and investment” [13].

With the pandemic, it has been shown that for a company to be successful, seeking profitability is inadequate. It is necessary to apply new business trends, where more digital, more global, and more sustainable businesses are required [12,13,14].

This work aimed to evaluate whether the reasons why entrepreneurs start a business influence their assessment of the socio-economic benefits of business incubators.

Although entrepreneurship and its relationship with economic and social growth have previously been studied in a broad and general way [4,5,6,15,16,17], there is a shortage of works that have focused on the economic and social sustainability capacity of incubators from the perspective of entrepreneurs [2,3,4].

Furthermore, although the relationships considered in this analysis have already been studied [18,19], the context and sample of our study are different. In this analysis, we focused only on Spanish entrepreneurs who are familiar with business incubators, and their perceived socio-economic benefits of business incubators.

This study identifies the opinions of entrepreneurs about the capacity of incubators to contribute to the promotion of sustainability in their projects. It offers the opportunity to redesign regional entrepreneurship policies based on the usefulness of business incubators to create social value.

This research is divided into five parts. The first part focuses on formulating hypotheses derived from the literature related to the motive for starting a business and the benefits of incubators to the sustainability of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. The methodology is also presented in this part. In the third part, the results are presented. The fourth part offers a discussion and, finally, the fifth part contains the discussion and conclusions of the work.

2. Materials and Methods

To study the differences in the assessment of the socio-economic benefits of business incubators according to the reasons for entrepreneurship, we chose two groups of entrepreneurs who had started a business for two different reasons: “to have the necessary resources” [10,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] and “to find difficulty when entering the labor market” [25,26].

2.1. Hypothesis Formulation

Having resources does not only imply economic means, which are undoubtedly relevant [20]. In addition, it must be at the lowest possible cost. The entrepreneur must develop sufficient capacities to maximize the benefits and profits of economic resources [21,22,23], leading to the highest profitability. The search for a source of financing is one of the essential activities of entrepreneurs [21,22,23], but this is not the only one. They must also know the general and specific area and field of business creation, contact networks, and technologies and generate knowledge about them to count on adequate and current machinery, raw materials with the lowest possible cost, services, and a place to operate [18,19]. Obtaining the best option is undoubtedly the most demanding and complicated job of entrepreneurship [24,25]. An entrepreneur that has the necessary resources and help from business incubators has an increased probability of the business succeeding of 40% [9] to 80–90% [18,24], and with it, socio-economic benefits are delivered to society. Business incubators are strategic partners for entrepreneurs as they contribute to a reduction in business creation transaction costs. Business incubators are also important for reducing the risk of death in the company and reduce uncertainty in the process [18].

The second reason considered most relevant for entrepreneurship by the entrepreneurs themselves is “because they have difficulties entering the labor market” [25,26], a reason integrated into the group of reasons for entrepreneurs by necessity. In this case, the entrepreneur has difficulties entering the labor market and, therefore, decides to start a business. It is not one of the best reasons since it can mean that sometimes they are not fully involved in the launch, start-up, and development of the activity [25].

However, [26] declares that entrepreneurship due to difficulties entering the labor market is not directly related to a clear need to find a way to earn money. In many cases, it is because the entrepreneur counts on the necessary training, knowledge about the area, skills and competencies for the business, and a network of contacts; however, for reasons about character and desirability, entrepreneurs do not want to work for others or respect the rules or schedules of companies, which makes it difficult for them to join the labor market. However, they have all the necessary resources to start a business.

The situation of economic paralysis caused by COVID-19 has left thousands of people jobless. Many of them have seen entrepreneurship as the best way to survive [12,27]. In the crisis of 2008, only 14% of entrepreneurs were entrepreneurs based on necessity while 80% were entrepreneurs due to opportunity. Nevertheless, such figures for 2017 and 2018, with the real estate bubble crisis, were 27% and 23% due to necessity and 63% and 70% due to opportunity, respectively [12].

Therefore, we can evidence that people who start businesses out of necessity grow in times of crisis. Despite this, in Spain, the spirit of entrepreneurship is low. In Canada, the rate of entrepreneurial activity was 18.7% in 2018, 17.9% in Brazil, and 15.6% in the U.S. [12] while in Spain, the rate was only 6.4% for the same year.

Furthermore, there is a great fear of failure [28]. The GEM report [12] revealed that 43% of the Spanish population between 18 and 64 years perceived that a fear of failure impedes them from deciding to undertake entrepreneurial action.

For this reason, entrepreneurship, out of necessity in many cases, is not a task for society but can benefit it and is an opportunity for entrepreneurs, who, for personal reasons, fear of failure, education or formation, etc., did not want to start a business but carried on with all the necessary resources to do so. Many entrepreneurs generally look for the best incubator to shorted their long journey [19], using business incubators as support mechanisms to increase their start-up experience and shorten the entrepreneurial learning curve [18,19].

In turn, the creation and support provided by business incubators to new businesses for them to grow and survive throughout their life cycle results in growth and economic development in society [12,29]. Furthermore, this increases the synergy between companies in the national economy, producing an increase in a company’s productivity and greater ease in obtaining R&D [10,30]. Business incubators, as allies of entrepreneurs, thanks to their services, experience, and expertise, help the latter to reduce their transaction costs, thus reducing the uncertainty and risk of possible early death of the company [18].

Therefore, the following hypotheses regarding the benefits of business incubators in “increasing employment in society” [12,28,31,32] are posited:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Entrepreneurs, having the resources necessary to do so, positively value business incubators’ impact on increasing employment in society.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Entrepreneurs who experience difficulties entering the labor market positively value the impact of business incubators in increasing employment in society.

The generation of startups means new jobs, which can be separated into two types: entrepreneur-employer (self-employment), and jobs for potential employees [31]. Business incubators play a critical role as mechanisms that encourage the creation of companies. According to a study conducted by the Madrid City Council from 2011 to 2019, the public incubators of the Community of Madrid created an average of 130 companies per year [32].

Studies by Panorama Laboral in the Madrid community [33], Funcas [4,7,34], and Madrid City Council [32] show that business incubators are very efficient tools for job creation. A study by GEM points out that its incubation program from 2020 to 2021 created 4200 direct and indirect jobs in just 2 years [12].

According to the Funcas report [4,7,34], after the first year of their creation, companies begin to hire workers to meet companies’ growth and the market demand.

The probability of the survival of newly created companies increases from 40% to 60% thanks to having the necessary resources. They positively value business incubators since they also help to increase the possibility of the survival of companies in a competitive market and thus create more jobs [7,31,34]. Their most essential functions are to promote the consolidation of new companies by minimizing startup costs and strengthening entrepreneurs’ figures by creating a suitable environment for their business development without the need for substantial investments [4,7,12,31,34].

Considering the previous arguments, the third and fourth hypotheses on the benefits of business incubators in “increasing innovation” [4,7,12,31,32,34,35] are provided:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Entrepreneurs, having the resources necessary to do so, positively value the impact of business incubators on increasing in innovation in society.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Entrepreneurs who experience difficulties entering the labor market positively value the impact of business incubators on increasing innovation in society.

Start-ups, as an integral part of the entrepreneurship ecosystem, play a critical role in the success of emerging markets. Without these entities, many market opportunities are not prone to being explored and exploited [14].

Another valued benefit of incubators for entrepreneurs who have the necessary resources is that they serve as a link between uncertainty and innovation.

Entrepreneurs not only consider business innovations as those related to the modifications, changes, or development of products/services but they are also aware that in many cases, they may involve new business models and/or business ideas that may lead to new business opportunities in current markets or new target audiences. This means that a competitive advantage can be achieved not only by the characteristics of the product/service but also by a higher level of efficiency, higher productivity, excellent service characteristics, or elements that accompany the product (complementary products) [30].

Therefore, innovation can be achieved whenever a product/service is offered more efficiently or effectively to better satisfy a customer’s needs. An example of this would be the case of the technology companies analyzed by Mattos [36]. He concluded that companies create innovation to better meet their customers’ needs and increase the synergy between their products [36]. Another example of innovation in new business models to increase their productivity or efficiency is the case of Mercadona’s co-innovation, as analyzed by Blanco-Callejo and De-Pablos-Heredero [37], a company that innovated from the customer backwards to satisfy the “boss” (customer) with products of the highest quality at the best possible price [14].

Taking into account that one of the main objectives of public business incubators is to promote innovative companies [31], there are even incubators that are mainly dedicated to incubating innovative or technological companies, as is the case of the public business incubator of Móstoles (Madrid) [38], where 80% of the incubated companies are related to R&D according to the director of this incubator, Ramírez, in the panel of experts conducted in 2019 by Lin-Lian [32,38].

The fifth and sixth hypotheses on the benefits of business incubators in “increasing the productivity of society” [30,31,32,37,38] are formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Entrepreneurs, having the resources necessary to do so, positively value the impact of business incubators on increasing the productivity of society.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Entrepreneurs who experience difficulties entering the labor market positively value the impact of business incubators on increasing the productivity of society.

The globalization process has led to a progressive reduction in the size of companies, which requires an increase in productivity levels linked to entrepreneurial activity. The most operative approach is to create small companies and choose to relocate the different stages of the production process. This is because smaller entities have more weight in creating employment, investment, and innovation, becoming the central piece of productivity growth according to the Office for Regional Policy of the Commission of the European Communities [39] and European Bussiness Centres Network [40].

The concept of the entrepreneur is defined in the law of the support to entrepreneurs (Ley 14/2013: 78792): “those persons, regardless of their status as individuals or legal entities, who will carry out or are carrying out a productive economic activity” [41]. To develop this productive activity, entrepreneurs must confront a wide range of variables that generate continuous changes in their business strategy.

Carree and Thurik [42] state that entrepreneurs are inclined to work longer hours and more efficiently since their income is directly linked to the hours worked. They positively value the influence of business incubators on the productivity of enterprises in society because they allow them to more efficiently obtain the required resources to undertake and better execute their productive economic activity [43,44].

Achieving the objective of economic growth and development is not an easy task, and, in this sense, the incubator is an instrument of economic development. This will only be the case if the efforts made are translated into productivity increases and, at the same time, a firm commitment is made to innovation [45,46].

Similar to any other economic policy instrument, business incubators have advantages and limitations: the nursery operator obtains significant savings in initial infrastructure costs, existing installations, and the creation of a space for entrepreneurs. Investment increases the incubator’s area, and economic activity is boosted [7,12,31,34].

The follow-up of these, both in the creation and subsequent maintenance, allows for higher levels of business creation and more efficient and productive companies. The increase in entrepreneurs with the necessary resources thanks to business incubators’ help positively impacts on their survival and productivity [45,46]. Business incubators’ functionalities that have the most substantial impact on productivity are networking activities [16,31] and the acceleration of high-potential projects, also in free coworking spaces [7,16,34].

Taking these arguments into consideration, we formulate the seventh and eighth hypotheses on the benefits of business incubators in “promoting the growth and economic development of society” [7,16,31,34,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Entrepreneurs, having the resources necessary to do so, positively value the impact of business incubators on the promotion of society’s growth and economic development.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Entrepreneurs who experience difficulties entering the labor market positively value the impact of business incubators on the promotion of society’s growth and economic development.

One of the most challenging resources for entrepreneurs is economic resources. Therefore, for businesses that, in the beginning, count on economic resources and the help of business incubators, the possibilities of success are more probable, increasing from a possible failure of 40% to only 10–20% in the first 5 years of life [7,24,34].

Although business incubators are not economically profitable at the beginning at the social level due to their requirement for economic support and public investment to start operating [46], they do have social profitability (above all, public business incubators) because the increase in business creation, employment, and revitalization of areas where the business incubators are located allows local public administrations, via taxes, to receive higher returns than those invested in these incubators [47,48]. According to the study by Sentana et al. [46], of the 43 business incubators in the autonomous community of Valencia that participated in the study, on average, the local administration collected 2.8 euros in taxes for every 1 euro spent on these entities [47,48].

Business incubators have a positive impact on the promotion of the growth and economic development of society according to the opinion of entrepreneurs with the necessary resources to start their business. As mentioned by Hansen, Ches-brough, Nohria, and Sull [49]; Blanco et al. [31]; Manigart and Sapienza [50]; Funcas [4,7,34]; GEM [12,51]; and INE [10], this increases the survival rate of companies during their first years of life by minimizing the costs at the beginning of their activity and providing advice and follow-up during incubation and when they graduate [2,31,34,50] and by contributing to the generation of employment of both a salaried and self-employment nature [7,10,12,34,49,51].

Therefore, the increase in the number of entrepreneurs and new businesses, driven in turn by business incubators, stimulates the economic growth and development of a given area as it increases and facilitates the movement of capital, resources, and capabilities, which puts a country’s national economy in a better position compared to other countries.

The ninth and tenth hypotheses on the benefits of business incubators in “increasing the social cohesion of society” [2,4,7,10,12,24,31,34,46,47,48,49,50,51] are formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Entrepreneurs, having the resources necessary to do so, positively value the impact of business incubators on increasing the social cohesion of society.

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

Entrepreneurs who experience difficulties entering the labor market positively value the impact of business incubators on increasing the social cohesion of society.

Economic growth without social growth leads to undesirable effects such as population displacement, violence, youth marginalization, indifference, and unemployment [52,53]. In this case, it would affect entrepreneurs with both economic and non-economic resources, which would mean a loss in both productivity and competitiveness for the local, regional, and national economy and reduced attraction of investors with resources in different local, regional, and national economic sectors [54].

Therefore, resourceful entrepreneurs play an important role as cohesive agents in the local, regional, and national ecosystem [55] since their profile allows for greater possibilities of success than other stakeholders and they are one of the main groups responsible for bringing about change in the management models of companies.

However, Ortiz and Millán [56] consider that it is equally essential for entrepreneurs to receive proper training in the social responsibilities they have as agents of the ecosystem to be socially responsible in society. Business incubators play a crucial role in this regard, primarily through the following two functions of this type of entity: advice and tutoring in all areas of entrepreneurs, including social and legal issues for the development of all kinds of ideas that intend to be implemented [7,34,57], and strengthening of the entrepreneurial capacity by creating a suitable environment for business development, solving, at all times, the problems that they may have in the various administrative, social, economic areas, etc., and advising them on the best options after an analysis of the cases by experts in the various areas, avoiding the involvement of third parties who are often untrained in the field [7,12,31,34].

Therefore, we can say that it is essential to retain entrepreneurs with resources in our ecosystem and attract entrepreneurs with resources from other economies [58] who receive proper social training through business incubators. Thanks to this type of entity, entrepreneurs stop being a risky adventurer who travels alone in the business world, becoming a driving force in the economy [31].

Next, the formulation of the eleventh and twelfth hypotheses on the benefits of business incubators in the “creation of companies in society” [7,12,31,34,52,53,54,55,56,57,58] is as follows:

Hypothesis 11 (H11).

Entrepreneurs, having the resources necessary to do so, positively value the impact of business incubators on creating businesses in society.

Hypothesis 12 (H12).

Entrepreneurs who experience difficulties entering the labor market positively value the impact of business incubators on creating businesses in society.

In any country, the creation of SMEs means economic growth and new jobs, including entrepreneur-employer (self-employment) and jobs for potential employees [31]. The more resources business partners have, the more economic growth the economy will experience. For entrepreneurs with resources, business incubators have a crucial role as a factor that encourages the creation of businesses, which is consistent with the study conducted by the Madrid City Council from 2011 to 2019, which showed that an average of 130 businesses were created annually in the public incubators of the community of Madrid [32].

According to the opinion of entrepreneurs, business incubators not only support the creation of new companies but also help them to grow and survive throughout their life cycle [7,29,34], and this, in turn, leads to an increase in the synergy between companies in the national economy [10,30], which, in turn, is enhanced and accelerated thanks to the fact that entrepreneurs have the necessary resources.

In summary, regardless of the reason why entrepreneurs start their activity, they positively value incubators as a mechanism to help explore the most suitable environment for the creation, improvement, and establishment of new business entities, providing a range of services to their customers [31] and providing a context that increases the probability of the success and survival of businesses [4,7].

2.2. Methodology

A questionnaire was developed to collect the opinions of a representative sample of entrepreneurs residing in Spain to assess the value creation of business incubators in society.

The sample was composed of 194 entrepreneurs residing in Spain. Spain was established as the demographic limit due to the significant development of business incubators compared to the rest of Europe [3,59]. The descriptive characteristics of our sample are shown in the following table (Table 1):

Table 1.

Descriptive table of the sample profile.

According to the number of subcontracted employees, this table shows that 74.74% of the microcompanies surveyed have less than two employees.

From the 194 surveys obtained, 60.31% are aware of the business incubators (117 companies). Therefore, the sample used for the study of the impacts of the socio-economic benefit of business incubators on society from the point of view of entrepreneurs with different motives for entrepreneurship included these 117 companies.

The survey mainly collected data on the impacts of the different functions of business incubators on the entrepreneurial ecosystem to assess the usefulness of business incubators in society.

To study the different evaluations depending on entrepreneurs’ motive for starting their activity, several variables were studied in the survey, divided into two large groups: one related to entrepreneurship due to necessity, e.g., unemployment and difficulty entering the labor market, and the other related to entrepreneurship due to vocation, e.g., desire to undertake and develop one’s project, having the necessary resources, independence, personal satisfaction, and happiness. However, only “having the necessary resources” [20,21,22,23,24] and “difficulty entering the labor market” [25,26] were found to be significant.

Questionnaires are one of the most widely used tools in social research, as they allow extensive information to be obtained from primary sources [46] on a particular topic of interest by presenting the set of items in the form of proposals [60]. However, the questionnaires also have disadvantages. Amongst them, we can stress two: one is the inadequate interpretation of the questionnaire by the interviewees and the second disadvantage is the difficulty in reaching reliability, since it whether the respondent suffers from occasional emotions or subjective opinions on the subject is unknown [60]. The first drawback has been attempted to be solved mainly by contacting entrepreneurs online, by phone, mail, social networks, etc. To avoid the second disadvantage, we chose to control the questions and use a Likert scale, which allows the questions to be closed and the results to be more precise, reducing ambiguities [46].

The survey was conducted online using the Google Surveys platform, and disseminated through social networks. Using the same tool, the responses were collected, and a descriptive analysis was conducted. The Google Surveys tool was chosen due to its ease of distribution and great reach [46], especially in unpredictable situations such as the current one caused by COVID-19 [27], but other means of contact with entrepreneurs such as telephone and online meetings were also used in order to achieve better dissemination.

Data were collected from 7 April 2020 to 19 September 2020, according to the schedule shown in the table below (Table 2):

Table 2.

Methodology schedule, date, and number of surveys collected.

The survey questions were measured using a Likert scale for entrepreneurs residing in Spain who are knowledgeable about business incubators. The evaluation was conducted using a Likert scale: 1: the respondent did not consider the factor important; 2: the factor is not very important; 3: the factor is considerably important; 4: the factor is important; and 5: the factor is very important.

Therefore, the geographic area is Spain. The information was collected using online surveys. Smart PLS was used to create the model. The sample was composed of 194 entrepreneurs. We obtained 117 valid surveys.

This work is part of a broader research study on the effects and impacts of business incubators on entrepreneurship. Questions were extracted from a more extensive questionnaire used in this research and divided into two blocks: reasons for entrepreneurship (block 1) and socio-economic benefits of incubators (block 2).

A group of variables was defined for each block. Therefore, two sets were used: those related to why entrepreneurs carried out their activity (REA) and those related to the benefits of incubators for society (ImBI). The values obtained in the descriptive analysis for each variable were also included.

To confirm the relationships between the motives for entrepreneurship and the valuation of the impacts of incubators on society, and to test the hypotheses highlighting the relationships, a structural equation model (SEM) was developed, since this method, unlike other multivariate methods used in the social sciences such as regression, where only one relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables are represented, can examine a series of dependency relationships simultaneously [61].

In SEM, multiple indicators are obtained to control the measurement error specific to each variable, which allows the researcher to evaluate and test the validity of each measured variable and the theoretical models [62].

Statistical analyses were performed using the partial least squares (PLS) method with SmartPLS3 software [63].

3. Results

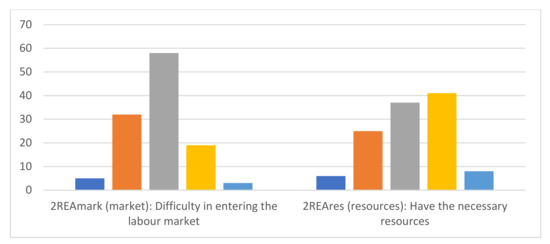

In Figure 1, the Likert-scale evaluation of the importance of the entrepreneurship factors according to the surveyed entrepreneurs is represented, and Table 3 shows the number of individuals and the average motive for starting a business in each group:

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of entrepreneurs’ assessment of the importance of entrepreneurship factors (Likert scale).

Table 3.

Calculation of the arithmetic mean of the importance of the entrepreneurial factors.

From the previous variables related to the entrepreneurial decision, we observed that for the sample surveyed, the most important reason was “I have the necessary resources” [20,21,22,23,24], with an average score of 3.17 out of 5. We observed that the reason “difficulty entering the labor market” [25,26] also had moderate importance in relation to the individual’s entrepreneurial decision (average of 2.85).

The following table shows the evaluation, mean and percentage of the evaluation of the different impacts of the business incubators on society by the entrepreneurs using a Likert scale (Table 4), with the highest mean (most important impacts) on a yellow background, and the lowest mean (least important impact) on a blue background:

Table 4.

Evaluation, average, and percentage (in parentheses) of the value of the different impacts of business incubators on society from the point of view of entrepreneurs (Likert scale).

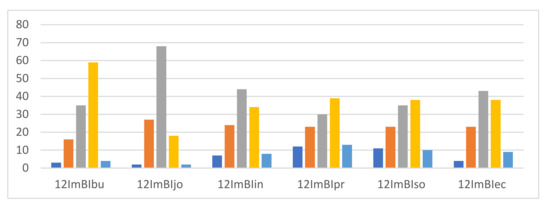

The following figure (Figure 2) shows graphically the entrepreneurs’ evaluation of the importance of the socio-economic impact of business incubators on society:

Figure 2.

Graphical depiction of the entrepreneurs’ evaluation of the importance of the impact of business incubators on society (from 1 to 5).

The three most significant impacts of the incubators for entrepreneurs were the creation of businesses, with an average of 3.38 out of 5. 83.76% of the 117 respondents; in second place, the promotion of economic growth and development, with an average of 3.21/5 and 76.93% of the respondents valuing it with more than a 3; and in third place, the increase in business productivity, with an average of 3.15/5 and 70.09% of the respondents valuing it with more than 3. Regarding the other impacts of the incubators on society, they were also considered important by the entrepreneurs, having the lowest impact score of 2.92 out of 5 and an average impact of 3.145, which shows that incubators have a strong impact on society from the point of view of entrepreneurs.

3.1. Model Analysis

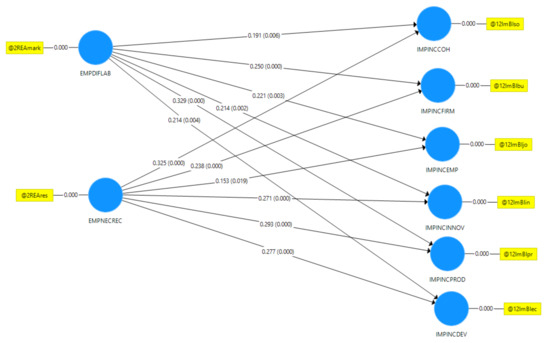

The proposed model (Figure 3) was estimated by bootstrap (5000 samples) using the Smart PLS 3 software. It was carried out in two stages [64]. In the first stage, the measurement models were evaluated, and, in the next stage, the structural model was built.

Figure 3.

Statistical model of the structural relationships between entrepreneurship motives and the benefits and impacts of business incubators on society.

Regarding the measurement models’ assessment, the internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) is higher than 0.7 (Table 5) and the indicator loadings (Table 6) are higher than 0.7. Concerning the convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) is higher than 0.5 (Table 5), as requested by the literature.

Table 5.

Construct reliability and validity.

Table 6.

Outer loadings.

The discriminant validity was verified using the Fornell–Larcker criterion (Table 7). This verified, as expected, that the AVE of each construct is higher than the construct’s highest’s squared correlation with any other construct. The cross-loadings matrix (Table 8) confirmed that a construct’s own indicator’s loadings are higher than its loadings on any other constructs.

Table 7.

Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Table 8.

Cross-loadings matrix.

Concerning the structural model, all the weights of the standardized paths were greater than 0.153, with p-values < 0.05 [65,66] (Figure 3).

As in the structural model, the significance of all its path values took a p-value of less than 0.05, and all the proposed hypotheses were accepted. The adjusted R2 of the different constructs is between 0.145 and 0.245, which acceptable within these types of research in the social sciences. This model does not present collinearity issues, with the VIF being lower than 2 (Table 9) [66,67].

Table 9.

Structural model variance inflation factor (VIF) values.

3.2. Acceptance/Rejection of the Hypotheses Proposed

Consequently, the following results can be confirmed:

H1. Entrepreneurs, having the resources necessary to do so, positively value the impact of business incubators on increasing employment in society (β = 0.153, p = 0.015 (p < 0.05)): accepted hypothesis.

The relationship between these two variables is positive and statistically significant (with a p value of 0.015). Therefore, higher scores in entrepreneurship with necessary resources are associated with an increase in employment in society.

H2. Entrepreneurs who experience difficulties entering the labor market positively value the impact of business incubators on increasing employment in society (β = 0.221, p = 0.003 (p < 0.05)): accepted hypothesis.

The relationship between these two variables is positive and statistically significant (with a p value of 0.003). Consequently, higher scores by entrepreneurs regarding the difficulty entering the labor market are associated with an increase in social cohesion. Therefore, the graphical representation is a linear function.

H3. Entrepreneurs, having the resources necessary to do so, positively value the impact of business incubators on the increase in innovation in society (β = 0.271, p = 0.000): accepted hypothesis.

The relationship between these two variables is positive and statistically significant (with a p value of 0.000). Thus, higher scores in entrepreneurship with necessary resources are associated with an increase in innovation in society. Hence, the graphical representation is a linear function.

H4. Entrepreneurs who experience difficulties entering the labor market positively value the impact of business incubators on increasing innovation in society (β = 0.214, p = 0.002 (p < 0.05)): accepted hypothesis.

The relationship between these two variables is positive and statistically significant (with a p value of 0.002). Therefore, higher scores by entrepreneurs regarding the difficulty entering the labor market are associated with an increase in innovation in society; therefore, the graphical representation is a linear function.

H5. Entrepreneurs, having the resources necessary to do so, positively value the impact of business incubators on increasing the productivity of society (β = 0.293, p = 0.000): accepted hypothesis.

The relationship between these two variables is positive and statistically significant (with a p value of 0.000). Therefore, higher scores in entrepreneurship with necessary resources are associated with an increase in productivity in society. Consequently, the graphical representation is a linear function.

H6. Entrepreneurs who experience difficulties entering the labor market positively value the impact of business incubators on increasing the productivity of society (β = 0.329, p = 0.000): accepted hypothesis.

The relationship between these two variables is positive and statistically significant (with a p value of 0.000). Therefore, higher scores by entrepreneurs regarding the difficulty entering the labor market are associated with an increase in productivity in society; therefore, the graphical representation is a linear function.

H7. Entrepreneurs, having the resources necessary to do so, positively value the impact of business incubators on promoting society’s growth and economic development (β = 0.277, p = 0.000): accepted hypothesis.

The relationship between these two variables is positive and statistically significant (with a p value of 0.000). Then, higher scores on entrepreneurship with necessary resources are associated with the promotion of economic growth and development in society; therefore, the graphical representation is a linear function.

H8. Entrepreneurs who experience difficulties entering the labor market positively value the impact of business incubators on promoting the growth and economic development of society (β = 0.214, p = 0.005 (p < 0.05)): accepted hypothesis.

The relationship between these two variables is positive and statistically significant (with a p value of 0.005). Consequently, higher scores by entrepreneurs regarding the difficulty entering the labor market are associated with the promotion of economic growth and development in society. So, the graphical representation is a linear function.

H9. Entrepreneurs, having the resources necessary to do so, positively value the impact of business incubators on increasing the social cohesion of society (β = 0.325, p = 0.000): accepted hypothesis.

The relationship between these two variables is positive and statistically significant (with a p value of 0.000). Therefore, higher scores on entrepreneurship with necessary resources are associated with an increase in social cohesion. Hence, the graphical representation is a linear function.

H10. Entrepreneur who experience difficulties entering the labor market positively value the impact of business incubators on increasing the social cohesion of society (β = 0.191, p = 0.005 (p < 0.05)): accepted hypothesis.

The relationship between these two variables is positive and statistically significant (with a p value of 0.005). Therefore, higher scores by entrepreneurs regarding the difficulty entering the labor market are associated with increased social cohesion in society. Then, the graphical representation is a linear function.

H11. Entrepreneurs, having the resources necessary to do so, positively value the impact of business incubators on the creation of businesses in society (β = 0.238, p = 0.000): accepted hypothesis.

The relationship between these two variables is positive and statistically significant (with a p value of 0.000). Therefore, higher scores on entrepreneurship with necessary resources are associated with higher levels of business creation in society.

H12. Entrepreneurs who experience difficulties entering the labor market positively value the impact of business incubators on the creation of businesses in society (β = 0.250, p = 0.000): accepted hypothesis.

The relationship between these two variables is positive and statistically significant (with a p value of 0.000). Therefore, higher scores by entrepreneurs regarding the difficulty entering the labor market are associated with a higher level of business creation in society. Then, the graphical representation is a linear function.

The following table (Table 10) shows the influence (on a scale of 0 to 1 normalized) of the variables related to entrepreneurs’ reasons with the impacts on society, reliability, and acceptance or rejection of the hypotheses:

Table 10.

Summary table: Acceptance/rejection of hypotheses according to the normalized indicator and p-value.

The condition that the variables 2 (2REAres and 2REAmark) of entrepreneurs’ reasons for starting their activity have an influence in a reliable and representative way is fulfilled in all hypotheses. All the hypotheses raised by the literature review were validated with a good level of reliability, as represented by the p value less than 0.05, and the influence was affirmed by the moderately medium high to moderately high p-values (from 0.153–0.329), with all of them being higher than 0.15.

Moreover, we observed that the greatest impact of the two entrepreneurship factors was on:

- The variable “difficulty entering the labor market” [25,26] to the variable “increase in the productivity of society” [30,31,32,37,38] from the point of view of entrepreneurs (0.329, modern high influence);

- Followed by the influence of the variable “having necessary resources” [20,21,22,23,24] on the variable “increasing social cohesion” [2,4,7,10,12,24,31,34,46,47,48,49,50,51] (0.325, moderately high influence);

- In third place, the influence of the variable “having the necessary resources” [20,21,22,23,24] on “productivity increase” [14,30,31,32,37,38] (0.293, moderately high influence);

- In fourth place, the variable “having the necessary resources” [20,21,22,23,24] to the variable “promoting economic growth and development” [7,12,27,30,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] (0.277, moderately medium-high influence). In fifth place, the same variable to “increasing innovation” [4,7,12,29,30,35,36] (0.271, moderately medium-high influence), and lastly, the influence of the variable “difficulty entering the labor market” [27,28] on the variable “business creation” [7,16,31,34,52,53,54,55,56,57,58] (0.250, moderately medium-high influence). Consequently, we can affirm that the model shows that the two factors studied influence entrepreneurship directly and in a moderately medium high to moderately high manner for all the factors studied (0.250, moderately medium-high influence). Therefore, we can say that the model shows that the two factors studied influence entrepreneurship directly and in a moderately medium high to moderately high manner for all the impacts studied in our hypotheses.

4. Discussion

This research analyzed the socio-economic benefits of business incubators oriented toward maintaining their sustainability in society through the valuation of entrepreneurs who have different entrepreneurial motivations.

From an empirical perspective, the model presented is consistent with the previous literature review, and the results show that all the hypotheses were validated. This means that the reasons why entrepreneurs start their activity do not influence their positive valuation of the benefits that business incubators have on the benefits in society. The hypotheses were validated with a high level of significance (p < 0.05).

The two reasons for entrepreneurship used for this study were “having the necessary resources” [19,20,68,69,70,71] and “difficulty entering the labor market” [25,26,27,28,68,69,70,72,73].

Studies conducted by the Madrid City Council and Funcas [4,7,32,34] show that incubators have a fundamental mechanism that promotes the creation of businesses based on an analysis of the number of businesses created in public incubators in the community of Madrid. This is consistent with the results of our model regarding H11 and H12.

This means that the entrepreneurial motives do not influence entrepreneurs’ positive evaluation of the benefits of business incubators in creating businesses in society. However, our study also shows that business incubators are effective in generating businesses in the community of Madrid.

According to studies conducted by the Madrid City Council, Funcas, and Panorama Laboral de la Comunidad de Madrid, the creation of new businesses is directly related to new jobs and an increase in employment, with these variables being directly and positively related. However, these studies are limited to the geographical limit of the community of Madrid [4,7,32,33,34]. Therefore, we found that the literature on the positive impact of business incubators on job creation coincides with the results of our model with respect to hypotheses one (H1) and two (H2).

The above statements, together with the literature review, show that business incubators help to increase the survival rate of businesses during their first years of life by minimizing the costs at the beginning of the activity and providing constant advice and monitoring during incubation. So, when they end this period [7,27,34,50], an increase in the number of entrepreneurs and new businesses that stimulate the economic growth and development of a determined area takes place, which coincides with the results of our model regarding H7 and H8.

The literature review also affirms that the appropriate training of entrepreneurs and future entrepreneurs, in which business incubators have a fundamental role, not only helps in the creation and survival of businesses but also in the development of new enterprises [4,7,10,12,31,32,33] while also producing an increase in social cohesion in society in general. This is because entrepreneurs are the leading promoters of the economy, so they have an essential role socially [31] to take care of their teams and company culture, since capturing talent and creating an excellent team is the only way for a company to grow on a large scale.

They conclude in the study that one of the best ways to capture and retain talent in companies is to have a proper culture and social responsibility [74], which supports the results of our model regarding H9 and H10.

A larger number of businesses and an increase in employment favor the circulation of capital, resources, and capabilities in the area, which places the national economy of a country in a better position compared to other countries [36], thus generating better synergies between them and, as a result, producing the effect of increased innovation. According to reports published by the Móstoles City Council and the Móstoles Business Incubator, their analysis of more than 80 companies incubated in the Móstoles Business Incubator (Madrid) since 2011 [31,32,34,38,59] showed that more than 50 were already graduated companies (having completed their incubation period) and 85% were innovative companies according to the manager of the Móstoles business incubator Ramirez [59]. Regarding the productivity in the society where they were located, according to the literature review performed, entrepreneurs are people who are inclined to work more hours and more efficiently since their income is directly linked to their work [42,45,46]. In the study conducted by Carree and Thurik [42] on an analysis of the GEM database and GDP growth in 36 countries, with the purpose of studying the effect of entrepreneurial activity on economic growth, they find a direct and positive relationship between both variables [42]. A study conducted by Eight Roads Ventures, one of the world’s extensive venture capital companies, in 2018 on entrepreneurs’ main aspirations based on interviews with 313 founders and co-founders of technology companies in Denmark, France, Germany, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom with a minimum income of one million dollars found that entrepreneurs are more ambitious regarding not only the economic issue but also that they are not happy with the current situation. Therefore, they are prepared to work more because they have the motivation to change the current situation in which they find themselves [74], which shows that the increase in entrepreneurs and businesses is directly related to the increase in the productivity of society, which supports the results obtained from our model regarding H3 and H4 on “benefits of business incubators in increasing innovation” [4,7,12,31,32,34,35] and H5 and H6 on “benefits of business incubators in increasing productivity” [27,28,32,36,37,38].

Because of this analysis, the research question is answered: Do business incubators create value in society regardless of why entrepreneurs start their activity? The answer is yes, and this answer was validated by the results achieved in this research.

5. Conclusions

The results of this work show the importance of business incubators that aim to make the entrepreneurial ecosystem more sustainable in society.

The relationship between business incubators and benefits regarding “business creation” (H11 and H12) is supported by our study’s high degree of agreement with the previous studies and confirms the findings of previous studies. As for the relationship between business incubators and “increased employment in society” (H1 and H2), the study conducted by GEM shows that its incubation program created 4200 direct and indirect jobs in just 2 years (from 2020 to 2021).

Regarding the relationship with the “increase in innovation” (H3 and H4), it is confirmed that business incubators promote the creation of new innovative businesses in Madrid, which is consistent with the results of our research regarding hypothesis 3 and hypothesis 4. Incubators have a positive impact on innovation, with the difference being that our study was limited to the Spanish territory. The results are based on information that came directly from the opinions of entrepreneurs.

The relationships between incubators and increased productivity (H5 and H6) with increased “social cohesion” (H9 and H10) and with the promotion of “economic growth and development” (H7 and H8) support the hypotheses, regardless of the reasons for which entrepreneurs start their activity. The results obtained in our study are consistent with the results of previous studies.

Therefore, in summary, we can affirm that the improvement of business incubators required exploration of the most suitable framework for the creation, development, and maturity of entrepreneurial experiences in a particular area regardless of the motives for entrepreneurship.

The main theoretical implication of this research is the construction of an SEM model based on the information gathered from direct surveys administered to entrepreneurs. This model allowed concrete data to be obtained from a specific profile: “Spanish entrepreneurs who have been in business incubators or know them”. This model allowed identification of the reasons why entrepreneurs start their activity and the socio-economic impact of business incubators in Spanish society, according to two different profiles of entrepreneurs: “entrepreneur due to necessity” and “entrepreneur due to vocation”. They both vary according to different socioeconomic characteristics and behaviors.

As the main practical implication, this study allowed deepening of the knowledge and opinions regarding the benefits of business incubators, identifying the usefulness of business incubators that impact on society. This work supports these entities as it takes a direct opinion of business incubators’ beneficiaries (entrepreneurs) of different profiles, providing a more accurate representation of this type of entity and making the benefits of these entities known. The results of this research also allow those responsible for managing this type of entity to make decisions on the future evolution of the benefits of incubators that are more oriented toward helping meet the real needs of entrepreneurs.

Therefore, a useful study is to justify the benefits that business incubators fulfill and help to promote them in society in order to improve entrepreneurship actions.

This work will help to decide on the areas of the benefits of incubators that should be promoted more because they are more important for entrepreneurs and will be useful to those responsible for the incubators in the design of policies, objectives, and plans for incubators: to undertake corrective or improvement measures that should be carried out both to benefit entrepreneurship in Spain and to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of incubators.

Surveys, as a method of collecting data, constitute the first limitation in this research. The sample itself is another limitation, in terms of the geographic area, being limited to the national boundaries of Spain.

Therefore, to complete this study, it is necessary to extend it to samples of entrepreneurs with a broader profile, including other regional, national, or international geographic areas and larger samples. It is also convenient to apply other methods of analysis in line with an investigation of the benefits of business incubators in society. Expansion of the reasons why entrepreneurs start their activity and other measures of impact assessment in the different fields of society are also welcomed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, all authors. Formal analysis, software, data curation, data processing, C.L.-L. and J.L.M.-B.; statistical analysis, C.L.-L. and J.L.M.-B.; validation and investigation, C.L.-L. and C.D.-P.-H.; supervision, J.L.M.-B. and C.D.-P.-H.; data acquisition, C.L.-L. All authors were involved in developing, writing, commenting, editing, and reviewing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article has been financed with funds from OPENINNOVA High Performance Research Group (URJC-V921) and the Bridge Research Project V946 -URJC entitled “The contribution of dialogic practices to teamwork quality: a proposal for evolving the relational coordination model.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the entrepreneurs who have provided data, support and time and have made possible the preparation of this work, and the Rey Juan Carlos University and public business incubators in Madrid who have offered the ideas and the resources to start with my work in the field of business incubators. Thanks to OPENINNOVA Research Group for their support to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cantillon, P. Teaching large groups. BMJ 2003, 326, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin-Lian, C.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Montes-Botella, J.L. Value Creation of Business Incubator Functions: Economic and Social Sustainability in the COVID-19 Scenario. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ochoa, C.P.; De Pablos Heredero, C.; Blanco Jiménez, F.J. How business accelerators impact startup’s performance: Empirical insights from the dynamic capabilities approach. Intang. Cap. 2020, 16, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, F.J.J.; Ackerman, B.V.; Polo, C.G.O.; Fernández, M.T.F.; Santos, J.L. Los Servicios Que Prestan los Viveros de Empresas en España: Ranking 2018/2019; Funcas: Madrid, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://www.funcas.es/libro/los-servicios-queprestan-los-viveros-de-empresas-en-espana-ranking-2018-2019-noviembre-2018/ (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Ferreiro Seoane, F.J.; Mendoza Moheno, J.; Hernández Calzada, M.A. Contribución de los viveros de empresas españolas en el mercado de trabajo. Contaduría Administración 2018, 63, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, R.; Grandi, A. Business incubators and new venture creation: An assessment of incubating models. Technovation 2005, 25, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, F.J.J.; Polo, C.G.O.; Fernández, M.T.F.; Santos, J.L.; de Esteban, D.E. Los Servicios Que Prestan los Viveros de Empresas en España: Ranking 2020/2021; Funcas: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://www.funcas.es/libro/los-servicios-queprestan-los-viveros-y-aceleradoras-de-empresas-en-espana-ranking-2020-2021/ (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Acs, Z.J.; Autio, E.; Szerb, L. National systems of entrepreneurship: Measurement issues and policy implications. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderete, R.Y.; Flores, L.E.; Mariño, S.I. Diagnóstico de Gestión del Conocimiento en una organización pública. In Proceedings of the XI Simposio Argentino de Informática en el Estado (SIE)-JAIIO, Córdoba, Spain, 4–8 September 2017; Volume 46, pp. 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). 2022. Available online: https://ine.es/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Agencia EFE. Las ‘Startups’ Españolas Captan Más de 1.434 Millones en lo Que va de 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.efe.com/efe/espana/1 (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Global Enterpreneurship Monitor. Global Enterpreneurship Monitor 2020/2021 Global Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Gobierno de Esapaña. El Gobierno Aprueba el Proyecto de Ley Crea y Crece Para Facilitar la Creación y el Crecimiento de Empresas. 2021. Available online: https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/ (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Salamzadeh, A. Start-up boom in an emerging market: A niche market approach. In Competitiveness in Emerging Markets; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2018; pp. 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Fernández, M.T.; Blanco Jiménez, F.J.; Cuadrado Roura, J.R. Business incubation: Innovative services in an entrepreneurship ecosystem. Serv. Ind. J. 2015, 35, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbers, J.J. Networking behavior and contracting relationships among entrepreneurs in business incubators. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 12032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aernoudt, R. Incubators: Tool for entrepreneurship? Small Bus. Econ. 2004, 23, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Hernández, J.G.; Magaña, R.D.S.G. Business incubators as allied in reducing the transaction costs in Mexican entrepreneurs. J. Entrep. Bus. Econ. 2014, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Salamzadeh, A.; Markovic, M.R. Shortening the learning curve of media start-ups in accelerators: Case of a developing country. In Evaluating Media Richness in Organizational Learning; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Olivos, T. Lo bueno, lo malo y lo feo: Las muchas caras de la evaluación. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Super. 2010, 1, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, R.E.A. El Emprendedor de Éxito; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, C.G.; Campillo, A.M.; Gago, R.F. Características del emprendedor influyentes en el proceso de creación empresarial y en el éxito esperado. Revista Europea Dirección Economía Empresa 2010, 19, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Del Junco, J.G.; Martínez, P.Á.; Zaballa, R.R. Características del emprendedor de éxito en la creación de pymes españolas. Estudios Economía Aplicada 2007, 25, 951–974. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, I.P. Organización Empresarial y de Recursos Humanos: ADGG0408; IC Editorial: Antequera, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- De Bes, F.T. El Libro Negro del Emprendedor. In Guia il Lustrada on es Mostra els Principals Problemes Que Tenen els Emprenedors a la Hora de Passar de la Idea al Desenvolupament de la Mateixa; Empresa Activa: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Alcaide, F.; Chica, L. Tu Futuro es HOY; Alienta Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S.A.; Sheikh, F.N.; Jamal, S.; Ezeh, J.K.; Akhtar, A. Coronavirus (COVID-19): A review of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. Cureus 2020, 12, e7355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.A.B.; García, M.L.S.; Adame, M.E.C. Hacia una comprensión de los conceptos de emprendedores y empresarios. Suma Negocios 2015, 6, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoane, F.J.F.; García, A.V. Los viveros de empresas como instrumento para el emprendimiento. In Proceedings of the Actas de la 4a Conferencia Ibérica de Emprendimiento, Pontevedra, Spain, 23–26 October 2014; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Fernández-Valero, G.; Blanco-Callejo, M. Supplier Qualification Sub-Process from a Sustained Perspective: Generation of Dynamic Capabilities. Sustainability 2017, 9, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, F.J.; Guseva, V.; López, C.M. Los viveros de empresas. Economistas 2012, 30, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Viveros de Empresas. 2021. Available online: https://www.madrid.es/ (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Panorama Laboral de la Comunidad de Madrid. 2018. Available online: https://www.ucm.es/aedipi/panorama-laboral-de-la-comunidad-de-madrid (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Blanco, F.J.J.; Polo, C.G.O.; Fernández, M.T.F.; Santos, J.L.; de Esteban, D.E.; Asencio, A.C.; Aguirre, J.C. Los Servicios Que Prestan los Viveros de Empresas en España: Ranking 2021/2022; Funcas: Madrid, Spain, 2022; Available online: https://www.funcas.es/libro/los-servicios-que-prestan-los-viveros-y-aceleradoras-de-empresas-en-espana-ranking-2021-2022/ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Qianqian, R.; Xindong, W. Application of Data Envelopment Analysis in Efficiency Assessment of Business Incubator: Taking Sci-Tech Business Incubators in Beijing as Example. Technol. Econ. 2011, 7, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dayan, R.; Heisig, P.; Matos, F. Knowledge management as a factor for the formulation and implementation of organization strategy. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 308–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Callejo, M.; de Pablos-Heredero, C. Co-innovation at Mercadona: A radically different and unique innovation model in the retail sector. J. Bus. Retail. Manag. Res. 2019, 13, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuntamiento de Mostoles. Mostoles Desarrollo: Viveros de Empresas. 2021. Available online: https://www.mostoles.es/ (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Dirección de Política Regional de la Comisión de las Comunidades Europeas (DG XVI). 2022. Available online: https://www.europeansources.info/corporate-author/european-commission-dg-xvi/ (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- European Bussiness Centres Network (EBN). 2022. Available online: https://ebn.eu/ (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Ley 14/2013, de 27 de Septiembre, de Apoyo a los Emprendedores y su Internacionalización. 2013. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2013-10074 (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Carree, M.A.; Thurik, A.R. Understanding the role of entrepreneurship for economic growth. Pap. Entrep. Growth Public Policy 2003, 1005, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.C.; Aldana, R.; Dios, S.D.; Yurrebaso, A. La Motivación y la Intención Emprendedora; Redalyc: Salamanca, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ripollés, M.; Blesa, A. Redes personales del empresario y orientación emprendedora en las nuevas empresas. Cuadernos Economía Dirección Empresa 2006, 26, 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- El Hussein, M.; Hirst, S.; Salyers, V.; Osuji, J. Using grounded theory as a method of inquiry: Advantages and disadvantages. Qual. Rep. 2014, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentana, E.; González, R.; Gascó, J.; LLopis, J. The social profitability of business incubators: A measurement proposal. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 116–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascigil, S.F.; Magner, N.R. Business incubators: Leveraging skill utilization through social capital. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2009, 20, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Redondo, M.; Camarero, C. Social Capital in University Business Incubators: Dimensions, antecedents and outcomes. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 599–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.T.; Chesbrough, H.W.; Nohria, N.; Sull, D.N. Networked incubators. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Manigart, S.; Sapienza, H. Venture capital and growth. In The Blackwell Handbook of Entrepreneurship; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Enterpreneurship Monitor. Global Enterpreneurship Monitor 2019/2020 Global Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-2019-2020-global-report (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Roundy, P.T.; Bradshaw, M.; Brockman, B.K. The emergence of entrepreneurial ecosystems: A complex adaptive systems approach. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I.; Definición de Encuesta. Promonegocio 2010. Available online: https://www.promonegocios.net/mercadotecnia/encuestas-definicion.html (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Mateus, J.R.; Brasset, D. La globalización: Sus efectos y bondades. Economía Desarrollo 2002, 1, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, A.F.S. El rol del empresario en la cohesión social. Criterio Libre 2011, 9, 127–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ortiz, P.G.; Millán, A.M.J. Emprendedores y empresa. In La Construcción Social del Emprendedor; Universidad de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.C.S.; Caggiano, V.; Sánchez, B.H. Competencias emprendedoras en la educación universitaria. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 3, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Carvajal, P.F.; Herrera-Sánchez, I.M.; Rueda-Méndez, S.; León-Rubio, J.M. El efecto de la conservación de recursos sobre la intención emprendedora en el contexto de crisis económica: El rol moderador de la autoeficacia y la creatividad. An. Psicol. Ann. Psychol. 2014, 30, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L. Business incubators: Mechanisms to boost business innovation capacity. Analysis of business incubators in the Community of Madrid. Esic Market Econ. Bus. J. 2020, 51, 73–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro de Lima, O.; Breval Santiago, S.; Rodríguez Taboada, C.M.; Follmann, N. Una nueva definición de la logística interna y forma de evaluar la misma. Ingeniare Rev. Chil. Ing. 2017, 25, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, A.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis; Kennesaw State University: Kennesaw, GA, USA, 2001; Volume 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlinger, F.N.; Lee, H.B.; Pineda, L.E.; Mora Magaña, I. Investigación del Comportamiento; MC Graw Hill: Mexico City, Mexico, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M.; SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH 2015. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modelling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Gedajlovic, E.; Lubatkin, M. A framework for comparing entrepreneurship processes across nations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2005, 36, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, F.C.; Spigel, B. Entrepreneurial ecosystems. USE Discuss. Pap. Ser. 2016, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo Martin, M.A.; Méndez Picazo, M.T.; Alfaro Navarro, J.L. Entrepreneurship, income distribution and economic growth. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2010, 6, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Reason, L.; Mumby-Croft, R.; Sear, L. Entrepreneurship education: Embedding practitioner experience. Rev. Int. Comp. Manag. 2009, 10, 598–610. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo, M.Á.; Méndez-Picazo, M.T. Innovation, entrepreneurship and economic growth. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaji, N.O.; Olugu, M.U.; Balogun, K.O. Innovative policies in technology business incubation: Key elements for sustainable entrepreneurship development in Nigeria. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2014, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Emprendedores. Eight Roads Ventures lanza un Fondo de 304 Millones de Euros Para ‘Start Up’ en Crecimiento. 2018. Available online: https://www.expansion.com/expansion-empleo/emprendedores/2018/03/20/5ab0d2a246163fa40e8b4621.html (accessed on 26 February 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).