Abstract

This study examined the effects of social support on the career exploration of university students in Pakistan. Nine hundred and seventy-three university students from Pakistan completed the measures of social support and career exploration. Regression analysis was applied to examine the impact of social support by family, friends, and significant others. The results revealed that career exploration is significantly predicted by family support (β = 0.063; p = 0.010), friend support (β = 0.081; p = 0.001), and teacher support (β = 0.065; p = 0.010). Moreover, total social support significantly predicts career exploration (β = 0.027; p = 0.003) of university students in Pakistan. These findings enhance our understanding of the factors influencing career exploration in university students. Further development of the research is discussed as well as possible educational implications.

1. Introduction

The topic of an individual’s career choice has become very popular and interesting among researchers these days. Career exploration is a significant part of most professional decisions, and choosing a career is one of most difficult tasks in life according to Kosine and Lewis [1]. The career development process is an ongoing, dynamic, and lifelong activity that needs to be carefully considered [2,3]. An individual explores activities, make decisions, and take on a variety of responsibilities through career exploration and career development [3,4]. Career development is linked to professional development [5,6] and involves the integration of educational, social, economic, physical, psychological, and chance factors that determine the nature and relevance of work across an individual’s life span [3]. Adolescence is the beginning of a person’s career development that continues throughout all of his/her life [7]. An individual in early life possesses two distinct stages of the career development process, which are career growth between the ages 4 and 13 and career exploration between the ages of 14 and 24 [7,8,9]. Previous studies found that the four explicit indicators of career choice include career planning, career exploration, career decisiveness, and the activities that involve career planning [10,11].

Career exploration is a key component of most professional decisions. Career exploration is a term that refers to intentional behaviors and cognitions that facilitate job-seeking information, professions, and organizations that were not introduced in the field in the past [12]. Career exploration is a multidimensional process of self-exploration considering the external environment, and it is the basic framework for career growth necessary for nurturing and expanding career development and job choice [13]. The career exploration process is concerned with how, where, and how much an individual searches, as well as the directedness continuum [13,14]. Career searching/exploration is necessary to assist students in efficiently directing their struggle in finding a job [1,15], and it is a crucial stage in an adolescent’s career development because it is linked to the school-to-work transition [7,16,17].

The investigation of identity and the formation of a core sense of self in connection with employment and career choices is among the most significant tasks for adolescents [7]. Although some adolescents engage in career exploration on their own, others may require assistance or support from social networks such as family, friends, and peers [18].

1.1. Career Exploration and Social Support

An important aspect related to the career exploration process is social support. Social support is perceived as providing support, assistance, or comfort to others, facilitating them to cope with psychological, biological, and social stressors in their life [19]. Social support is usually described by the characteristics of the social environment, social networks, and the benefits that they bring [20,21]. The positive impacts of social support on career exploration have been described by researchers [21,22]. Social support as multifaceted conception is characterized by the information that enables people to believe they are cared for, respected, and loved [23]. The psychological and material resources offered by an individual’s interpersonal relationships constitute social support [23]. Social support occurs when individuals consider their social interaction advantageous [24]. Support might occur from any interpersonal connection, including family members, friends, colleagues, or support groups [20,21]. The structural elements of a social network, as well as the perceived availability of resources, are indicated by social support [20,21]. Social support is a specific type of help provided by one’s family, peers, and colleagues to solve certain problems [23]. Social support can be psychological or material resources provided by social networks such as friends, family members, and coworkers to help others [23].

Social cognitive career theory states that cognitive characteristics, individual agency, and contextual aspects interact to grow a person’s career development [10,25,26]. To date, research concentrating the prediction of career choices in the academic realm, as well as the evaluation of the career decision-making process of university students, has overwhelmingly supported in social cognitive career theory [21]. Despite its contributions, this framework has yet to be used to discover the factors that influence students’ career choices. Lately, researchers have been found to be interested in investigating social–contextual elements that facilitate or hinder career development [10,21,25,27]. Research has explored strong associations of high levels of perceived social support with one’s belief about choosing a specific career [21,22,28]. For example, Chan conducted a study on the relationship among the social support, career exploration, career choice, and career self-efficacy of college students in Taiwan [21]. He found a strong positive association between the social support and career exploration of students [21]. Furthermore, Hui et al. found a significant association between perceived social support and career adaptability among adolescents in Hong Kong [22]. It was also reported in a previous study that teachers’ behavior and motivation played a significant role in career choice by the students [29]. Moreover, students’ career decision-making and social support from family and teachers were positively associated in a study in Bangladesh [30]. Interacting with parents, coaches, and peers, as well as receiving support from them, might boost students’ confidence in dealing with challenges related to career development [10,25]. Family support has a significant impact on one’s career choices and self-efficacy [21,31,32,33]. Furthermore, it is believed that when adolescents face goals such as continuing their education or starting a career after graduation, parental and teacher support had a beneficial impact on career exploration and choice [21,31,33,34].

Jiang argued that it is required to incorporate a vibrant life-span perspective to enhance our knowledge regarding career exploration and examine the multilevel factors and mechanisms involved in career exploration or self-exploration regarding work [8]. Further, Turan [27] analyzed the effect of perceived social support as far as the career exploration of adolescents is concerned. The authors found that peer support, family support, and significant others substantially precited career exploration among adolescents, suggesting the exploration of multilevel effects on career exploration [27]. Nevertheless, an extensive study emphasizing the psychological factors that may help career choice is required. Lately, detailed studies based on an appropriate theoretical framework that could explicitly provide the backdrop for interventions designed to support university students in the process of making career choices is required. The relationship between perceived social support from family, peers/friends, and teachers and career exploration has not been studied yet, particularly in the context of Pakistani university students.

1.2. The Current Study

Although the previous research has addressed the factors influencing the career development, career decision-making, and career choice of adolescents in Pakistan, there are a lot of gaps to fill in the current body of knowledge. Furthermore, not all sources of social support have been described in a concurrent model like in the present study. For instance, a study in Pakistan exhibited the positive effect of family on the career choice of undergraduate university students in Pakistan; however, other significant sources of social support, such as friends and teachers, were not included [35]. Moreover, there is research describing different results than the previous one. For example, Sharif et al. conducted a study on factors affecting students’ career choice [36]. The authors found a significant effect of fathers on the career choice of their children, but no statistical influence of mothers and tutors on students’ career choice, which is quite surprising [36]. On the other hand, the research did not see the effect of peers/friends, which has been reported to be a stronger predictor of career exploration than other sources of social support [37]. The current study also includes the effect of peers’ or friends’ support on the career exploration of adolescents. There is only once exception considering all sources of social support affecting students’ academic career choice in Pakistan [37]. However, the sample was taken from only one university. A study with a larger sample may generate different results. Furthermore, Akosah et al. presented a systematic review on the factors influencing career choice by focusing on the role of culture [38]. The authors found that the adolescents in a collectivistic culture such as Pakistan are mainly influenced by the parents or family expectations [38]. It is further argued that further research is imperative to guide the understanding of parental influence and diversity. Above all, Pakistan is in the process of creating a career guidance system that is affected by political, cultural, and professional challenges [39]; therefore, research on factors affecting career-related constructs would be of great importance to understand and grow the system effectively.

Based on the abovementioned literature and social cognitive career theory, the current study was designed to investigate social support and career exploration in a concurrent model. The aim was to look into the relationship between perceived social support and career exploration. Career exploration was considered as an outcome, whereas perceived social support was considered as a predictor variable in this study. The hypothesis was the positive association of perceived social support with career exploration. Social support was found to be involved in making the transition from school to professional life smoothly [40]. The purpose was to verify whether perceived social support predicts adolescent career exploration. This viewpoint implies that some elements viz perceived social support from friends, parents, and significant others impacts career development.

1.3. Covariates

Various demographic factors were identified as being associated with practices of career exploration and social support. The variables included gender, age, and socioeconomic status (SES). It is believed that males receive less social support and more career barriers than females [41,42]. Career exploration is reported to be higher in males than in females [43]. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that SES has played an essential role in career exploration. Students with lower SES are reported to have a lack of network and work commitments [44]. Moreover, younger age is correlated with more career exploration and older age with less career exploration [8]. Hence, it is expected that a study based on social support affecting career exploration may exhibit gender, age, and SES differences in the association.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Data were collected from undergraduate students in Pakistani universities. Participants were conveniently chosen from the first year (673) and second year (300) of their university classes. It took 15 min to fill out the questionnaires. We distributed approximately 1200 surveys, and 1023 of them were returned, with a response rate of 85.25%. The cases with missing values were removed, and we received 973 useable cases for data analysis. There were 645 (66.3%) males and 328 (33.60) females in total. The students participated in the study on the basis of informed consent. Individuals in the study ranged in age from 18 to 21 years old (mean age = 19.48 ± 0.99). The characteristics of the participants are reported in Table 1. Students voluntarily participated in the study. The survey was administered face to face by one of the researchers, who explained the study objectives to all participants prior to the administration of the scales.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

2.2. Measures

Measures for interpersonal factors and career exploration were administered to the students. All tools were used in English, as students at universities in Pakistan are taught in English. In addition, information about the following concurrent variables were collected: age, gender, and SES. SES was measured on 3 points, which were 1 = lower class, 2 = middle class, and 3 = upper class.

2.2.1. Interpersonal Factors

We adopted a self-report measure of perceived social support for career development from previous research [45] to assess interpersonal factors in the current study. The scale contains 12 items assessing adolescents’ career exploration. All items were evaluated on 7-point Likert scale (1 = very strongly disagree to 7 = very strongly agree). “Family,” “friends,” and “significant other” are three factors on the scale that measure perceived social support. The term “significant others” was changed to “teachers” in the current study. “My family truly tries to help me” and “My friends really try to help me” are two examples. The total score is computed by taking the sum of all items. There are no reverse items in the scale. The scale was revalidated in the Pakistani setting. We used the scale in its original form by changing a few words based on Pakistani society and university students (Appendix A).

2.2.2. Career Exploration Scale

The scale for career exploration was taken from a previous study [46]. The scale is one of the sub-components of the career and talent development self-efficacy scale. The scale is a self-report measure of career exploration containing six items. The items are evaluated from 1 (not confidence at all) to 5 (completely confident). The scores in the scale range from 5 = low level of career exploration to 30 = high level of the career exploration. The total score on the scale is the sum of all the items. We used the scale in its original form by changing a few words based on Pakistani society and university students.

2.3. Data Analysis

Missing values were excluded from the data. Then, the tools were validated in the Pakistani setting. First, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was computed and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was applied to see whether the factor structure fit into the data. Then, descriptive statistics were computed by using the mean and standard deviations. Pearson correlation was calculated to scrutinize the association among all study variables. Furthermore, regression analysis was used to examine the effect of social support by family, friends/peers, and teachers on students’ career exploration. An independent sample t-test was applied to verify gender differences. Age and SES differences were also analyzed by applying one-way ANOVA. Students differed in acquiring social support with different age and different SES. However, they were not different in their career exploration. Hence, SES and age were entered into covariates. Bivariate correlation was run to see the association among study variables, and regression analyses were used to investigate the impact of social support by family, peers/friends, and teachers on adolescents’ career exploration.

3. Results

3.1. Validity and Reliability

Before descriptive analysis, EFA and CFA were performed to explore factors and confirm whether the data fit into the model. EFA (see Table 2) generated a single factor for career exploration, with Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) = 0.88 (p < 0.001) and 71.39% variance explained. However, social support comprised three factors, with KMO = 0.94 (p < 0.001) and a variance explained of 84.65%. The reliability was checked with Cronbach’s alpha. Both tools where reliable, as the alpha value for career exploration was 0.92 and for social support was 0.96. Convergent validity was checked in terms of average variance extracted (AVE). The tools had convergent validity, as AVE was above 0.5 and composite reliability (CR) was greater than AVE (see Table 3). The discriminant validity was also established, as maximum shared variance (MSV) was less than AVE and the under-root of AVE was greater than the correlations between study constructs [47]. Moreover, construct validity was also ascertained, as the model fit indices were according to the standard [47,48]: The ratio of Chi-square to degree of freedom (χ2/df) was 4.35, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.93, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.073, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.058, and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.92. Table 2 reports the tool validation data.

Table 2.

Convergent validity, discriminant validity, and reliability of tools.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

3.2. Common Method Bias

Research reports that the results from cross-sectional data might be threatened by common method bias [49]. Hence, common method bias was assessed using the Herman one-factor test. The test was run in SPSS with principal component analysis. Four factors were extracted with eigenvalues greater than one. The first factor had 37.43% variance, which shows that data had no common method bias.

3.3. Differences in Demographic Factors

The results from the independent sample t-test revealed that there was no significant difference (t (971) = 0.19, p = 0.84) between males (M = 58.99, SD = 14.74) and females (M = 59.17, SD = 13.21) for overall social support. Furthermore, family support for boys (M = 20.36, SD = 5.36) and girls (M = 20.44, SD = 4.95) was also not statistically different (t (971) = 0.22, p = 0.83). Moreover, there was no significant difference (t (971) = 1.05, p = 0.29) between males (M = 19.33, SD = 5.12) and females (M = 19.69, SD = 4.72) in receiving support from friends for career exploration. Furthermore, social support from teachers was also statistically insignificant (t (971) = 0.71, p = 0.47) for males (M = 19.30, SD = 5.11) and females (M = 19.05, SD = 4.97). Likewise, males (M = 20.62, SD = 3.89) were not different than females (M = 20.45, SD = 4.07) in career exploration ((t (971) = 0.61, p = 0.54).

Furthermore, it was found that the social support is significantly different for different age groups (F (3, 969) = 3.33, p = 0.019), with 18-year-old adolescents (M = 56.58, SD = 13.27) receiving the least social support and 21-year-olds the highest social support (M = 61.16, SD = 15.66). Social support for 19-year-olds (M = 59.04, SD = 13.81) and 20-year-olds (M = 59.58, SD = 14.28) was almost the same. On the other hand, career exploration of adolescents in different age groups was not statistically different (F (3, 969) = 0.93, p = 0.43).

Moreover, adolescents from different SES were significantly different in receiving social support (F (2, 970) = 7.27, p = 0.001), with adolescents from upper (M = 65.54, SD = 13.56) and middle classes (M = 59.71, SD = 13.93) exhibiting more social support than the adolescents from the lower class (M = 56.47, SD = 14.80). On the other hand, career exploration of adolescents from different social status was not statistically different (F (2, 970) = 0.59, p = 0.55).

As career exploration was not different for different genders, age groups, or SES, no variable was entered as covariate in the main analysis.

3.4. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 3 indicates mean (M) values, standard deviation (SD), and correlation coefficients, showing relationships between career exploration and interpersonal factors. It was observed that among the interpersonal factors, family social support had the highest mean (M = 20.38, SD = 5.22), whereas teacher social support had the lowest mean (M = 19.22, SD = 5.07). Contrariwise, the mean for friend/peer social support was 19.45, and that for career exploration was 20.57. It is further depicted that social support by family, social support by friends, and social support by teachers all had a positive relationship with the career exploration of students. Career exploration was positively associated with social support from family (r = 0.083, p < 0.01), perceived social support from friends (r = 0.102, p < 0.01), and perceived support from teachers (r = 0.084, p < 0.01). In addition, overall social support was also significantly positively related to career exploration (r = 0.096, p < 0.01).

3.5. Regression Analyses

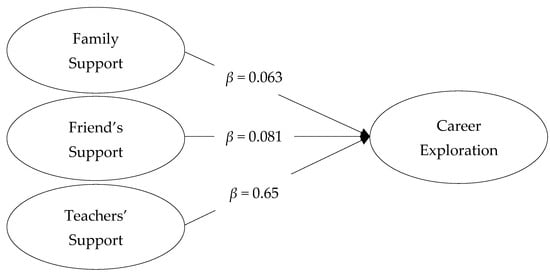

Table 4 presents the results of regression analysis. The table shows that career exploration was significantly predicted by family support (F (3) = 6.74, β = 0.063; p = 0.010), friend support (F (3) = 10.26, β = 0.081; p = 0.001), and teacher support (F (3) = 6.73, β = 0.065; p = 0.010). Moreover, total social support significantly predicted career exploration (F (3) = 8.998, β = 0.027; p = 0.003) of university students in Pakistan. The variance explained in career exploration by social support was 9.6%.

Table 4.

Social support predicting career exploration.

The structural model in Figure 1 exhibits the positive impact of family support, friend support, and teacher support on the career exploration of adolescents.

Figure 1.

Social support affecting career exploration.

4. Discussion

Contributing to the literature, the current study validates a conceptual model reflecting the association of social support with students’ career exploration. It was hypothesized that interpersonal factors such as family, friends, and teachers would positively affect the career exploration of students. The hypothetical model in our study suggests the importance of a theoretical framework predicting career exploration in university students in Pakistan.

The analyses of differences in demographic factors indicate that there was no significant difference between males and females in receiving social support in terms of career exploration. The results contradict previous research indicating that males receive less social support than females [41,42]. Furthermore, the present findings indicate that males and females were not significantly different in career exploration. Opposite to the current finding, previous research has explored significant differences between boys and girls in the activity of career exploration [43]. Career exploration in males was higher than that of females [43]. The lack of gender differences in the career exploration of Pakistani university students suggests the necessity and importance of developing equal career education irrespective of gender. Furthermore, consistent with previous research [50], no age-related or gender-related differences were found in career exploration. On the other hand, adolescents with different SES did show different career exploration, as opposed to past research [44].

Then, the correlation among study variables was estimated. It was found that there was significant correlation between interpersonal factors and adolescents’ career exploration. In line with past research [35,36,37], family support, peer or friend support, and teacher support for career exploration was positively related to the career exploration of adolescents. However, the highest correlation was between friend support and career exploration. This echoes the results of Arif et al., who reported peer support as a stronger predictor of career exploration than any other sources of social support [37]. The present findings are also consistent with previous research that found a significant correlation between interpersonal support and career exploration [10,21,27].

Next, regression analysis revealed that career exploration was significantly and substantially predicted by family support, friend or peer support, and teacher support. The study results demonstrate that there was a substantial effect of family support on career choice of university students. This finding is in line with the previous body of research [21,37] that presented a significant association among social support by family, friends, significant others, and career exploration. The current findings also echo the results of a systematic review that found that youth careers are mainly influenced by family expectations and guidance, as parents increased career confidence and career self-efficacy [38]. Humayon et al. also argued that family support significantly influences the career choice of undergraduate university students [35]. This suggests that families should encourage their children to engage in career exploration or self-exploration [38]. Furthermore, the study described that interpersonal factors such as perceived friend support also predicted career exploration substantially. This finding means that the higher the perceived level of support from peers/friends, the higher the level of career exploration would be. Several empirical studies [21,37] and a review study [8] on Asian culture confirmed the significant impact of peer/friend support on the career exploration of university adolescents. The result implies that support from peers or friends at university would be beneficial in making decisions about future careers. Moreover, teacher support positively predicted career exploration. In association with Sharif’s perspective, teachers’ support of career choice determines an adolescents’ careers in the future [36]. It implies that if students are motivated by the teachers about a certain profession, they would prefer to choose that career. The study also echoes the findings of another recent study in Bangladesh that authenticated the significant effect of teachers on students’ career exploration [30].

5. Limitations

This research is limited to subjective assessment of study factors. Although we feel that students’ subjective experiences are crucial to understand, the objective assessment of constructs (e.g., career exploration and sources of interpersonal support) may indicate a different form of outcomes. Despite its limitations, the present study contributes to a better understanding of the interpersonal support systems that are likely to contribute to adolescents’ career exploration.

6. Implications and Further Developments

There are several implications that could be discussed regarding the educational applications of the current findings. Our results could help to elaborate the relationship between social support, career exploration, and professional growth by presenting a model associating social support with career exploration. Considering that social support sources could play a role in the career exploration process, it is crucial to develop educational strategies that consider this variable, organizing activities to enhance students’ awareness of career exploration through social support.

The findings of this study have implications for future research on the relationship between social support and career exploration and suggest that additional study in this field is needed. Because the existing sample groups are only of Pakistani university adolescents, more research is suggested to examine different samples of students in Pakistan (e.g., college and school students). Moreover, future studies may recruit participants from different countries and continents in order to develop a large international comparison. Another option might involve the use of additional quantitative tools measuring different constructs such as motivation, self-efficacy, and identity development, reaching a significantly number of participants and inspiring a more comprehensive assessment of the characteristics of career exploration.

7. Conclusions

The current study reports research on the effect of interpersonal factors on the career exploration of Pakistani university students. Underpinning this research is the social cognitive career theory. This study’s research model is based on the evidence gathered from 973 university students in Pakistan. After analyzing the data, we found that family support, peer/friend support, and teacher support for career choice directly predicted the career exploration of adolescents. Therefore, social support is necessary for adolescents in the process of making a career decision. The significance of interpersonal factors for understanding career exploration of university students in Pakistan has been determined by the current study.

Author Contributions

For this research, S.K. (Sumaira Kayani) and H.K. wrote the original draft of the article. W.L. supervised the whole work. M.B. critically analyzed the research, and reviewed and edited the article. S.K. (Saima Kayani) wrote the Materials and Methods section, and K.K.R. contributed to data collection from Pakistan. S.K. (Sumaira Kayani) and H.K. contributed equally to the research. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted per the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013) and the Code of Ethics and Conduct of the British Psychological Society (2009). The Institutional Review Board of Zhejiang Normal University granted ethical approval for data collection, and all subjects gave their informed consent before taking part in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

An informed consent was signed by the participants before they filled questionnaires.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available with the first author on request.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge Zhejiang Normal University for providing me the opportunity to carry out a postdoc.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Social support scale.

Table A1.

Social support scale.

| Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

|

Total Score: Social support (SS) = sum (SS1 to SS12). Dimension scores: Family support: FaSS = sum(SS3, SS4, SS8, SS11); friend support: FrSS = sum (SS6, SS7, SS9, SS12); teacher support: TSS = sum (SS1, SS2, SS5, SS10).

Table A2.

Career exploration scale.

Table A2.

Career exploration scale.

| Items: I Am Confident That I Can… | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

|

Total Score: Career exploration (CE) = sum (CE1 to CE6).

References

- Kosine, N.; Lewis, M. Growth and exploration: Career development theory and programs of study. Career Tech. Educ. Res. 2008, 33, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, K.A.; Sutherland, D. History repeats itself: Parental involvement in children’s career exploration. Can. J. Couns. Psychother. 2013, 47, 239–255. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, M.; Hammer, S.; McIlveen, P. Mapping graduate employability and career development in higher education research: A citation network analysis. Stud. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A.; Koen, J. Contemporary career orientations and career self-management: A review and integration. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 126, 103505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutti, M.; Concina, E.; Frate, S.; Delen, I. Teacher professional development: Experiences in an international project on intercultural education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutti, M.; Concina, E.; Frate, S. Social sustainability and professional development: Assessing a training course on intercultural education for in-service teachers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, D. Life-Span, Life-Space Career Theory and Counseling. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Newman, A.; Le, H.; Presbitero, A.; Zheng, C. Career exploration: A review and future research agenda. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 338–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H.; Rudolph, C.W.; Todorovic, T.; Ammann, D. Academic career development: A review and research agenda. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Morris, T.R.; Penn, L.T.; Ireland, G.W. Social–cognitive predictors of career exploration and decision-making: Longitudinal test of the career self-management model. J. Couns. Psychol. 2019, 66, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Career decision making, fast and slow: Toward an integrative model of intervention for sustainable career choice. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 120, 103448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, R.; Jin, Q. Impact of a career exploration course on career decision making, adaptability, and relational support in Hong Kong. J. Career Assess. 2016, 24, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paixão, O.; Gamboa, V. Autonomous Versus Controlled Motivation on Career Indecision: The Mediating Effect of Career Exploration. J. Career Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esters, L.T. Influence of Career Exploration Process Behaviors on Agriculture Students’ Level of Career Certainty. J. Agric. Educ. 2008, 49, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusran, N.A.; Puad, M.H.M.; Omar, M.K. Role of Career Exploration in Influencing Career Choice among Pre-University Student. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2021, 29, 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M.L. Career adaptability: An integrative construct for life-span, life-space theory. Career Dev. Q. 1997, 45, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, D.E. A Life Span, Life Space Perspective on Convergence; CPP Books: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jemini-Gashi, L.; Duraku, Z.H.; Kelmendi, K. Associations between social support, career self-efficacy, and career indecision among youth. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 4691–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA. Social Support. Available online: https://www.scribbr.com/apa-examples/website/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Golden, T.D.; Gajendran, R.S. Unpacking the role of a telecommuter’s job in their performance: Examining job complexity, problem solving, interdependence, and social support. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-C. The relationship among social support, career self-efficacy, career exploration, and career choices of Taiwanese college athletes. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2018, 22, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, T.; Yuen, M.; Chen, G. Career adaptability, self-esteem, and social support among Hong Kong University students. Career Dev. Q. 2018, 66, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, W.; Juntunen, M.; Shirazi, F.; Hajli, N. Consumers’ value co-creation in sharing economy: The role of social support, consumers’ ethical perceptions and relationship quality. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 151, 119786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vietze, D. Social support. Encycl. Adolesc. 2011, 2, 341–351. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R.W.; Ezeofor, I.; Morrison, M.A.; Penn, L.T.; Ireland, G.W. Applying the social cognitive model of career self-management to career exploration and decision-making. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 93, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendling, E.; Sagas, M. An application of the social cognitive career theory model of career self-management to college athletes’ career planning for life after sport. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, E.; Çelik, E.; Turan, M.E. Perceived social support as predictors of adolescents’ career exploration. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2014, 23, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-H.; Fu, C.-M.; Li, R.-H.; Lou, J.-H.; Yu, H.-Y. Relationships among social support, professional empowerment, and nursing career development of male nurses: A cross-sectional analysis. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2012, 34, 862–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuatul, M.; Setyabudi, I.; Nugroho, S.I.; Indah, U. The effect of teaching quality on student career choice: The mediating role of student goal orientation. Интеграция Образoвания 2019, 23, 541–555. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiky, M.; Akter, S. The Students’ Career Choice and Job Preparedness Strategies: A Social Environmental Perspective. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2021, 10, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Islam, T.; Usman, A. Predicting entrepreneurial intentions through self-efficacy, family support, and regret: A moderated mediation explanation. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 13, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, A.; Puig, N. Personal strategies for managing a second career: The experiences of Spanish Olympians. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2016, 51, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-C. Factors affecting career goals of taiwanese college athletes from perspective of social cognitive career theory. J. Career Dev. 2020, 47, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yean, T.F.; Chin, T.L. Parental Influence and Undergraduates’ Career Choice Intentions. Sains Hum. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humayon, A.A.; Raza, S.; Khan, R.A. Effect of Family Influence, Personal Interest and Economic Considerations on Career Choice amongst Undergraduate Students in Higher Educational Institutions of Vehari, Pakistan. Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2018, 7, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, N.; Ahmad, N.; Sarwar, S. Factors influencing career choices. IBT J. Bus. Stud. 2019, 15, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, S.; Iqbal, J.; Khalil, U. Factors influencing students’ choices of academic career in Pakistan. FWU J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 13, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Akosah-Twumasi, P.; Emeto, T.I.; Lindsay, D.; Tsey, K.; Malau-Aduli, B.S. A systematic review of factors that influence youths career choices—The role of culture. Front. Educ. 2018, 3, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, G.; Hooley, T.; Neary, S. Careers work in higher education in Pakistan: Current practice and options for the future. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2020, 48, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.A.; Blustein, D.L.; Bohlig, A.J.; Platt, M.G. The college-to-career transition: An exploration of emerging adulthood. J. Couns. Dev. 2010, 88, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-C.; Wu, Y.-P.; Wan, Y.-P.; Zeng, Y.; Tang, X.-R.; Wang, L.-R. Effects of attribution retraining on the perceived career barriers of undergraduate nursing students. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2015, 2, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Holloway-Friesen, H. Acculturation, enculturation, gender, and college environment on perceived career barriers among Latino/a college students. J. Career Dev. 2018, 45, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, H.; Ling, H.; Gu, X. How do students become good workers? Investigating the impact of gender and school on the relationship between career decision-making self-efficacy and career exploration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordósy, R.; Clark, T. Beyond the compulsory: A critical exploration of the experiences of extracurricular activity and employability in a northern red brick university. Res. Post Compuls. Educ. 2018, 23, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, M.; Gysbers, N.C.; Chan, R.M.; Lau, P.S.; Shea, P.M. Talent development, work habits, and career exploration of Chinese middle-school adolescents: Development of the career and talent development self-efficacy scale. High Abil. Stud. 2010, 21, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, B.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. Common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, L.; Ginevra, M.C.; Santilli, S.; Nota, L.; Sgaramella, T.M.; Soresi, S. Career exploration and occupational knowledge in Italian children. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2015, 15, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).