Social Marketing Plan to Decrease the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Senior Citizens in Rural India

Abstract

:1. Introduction

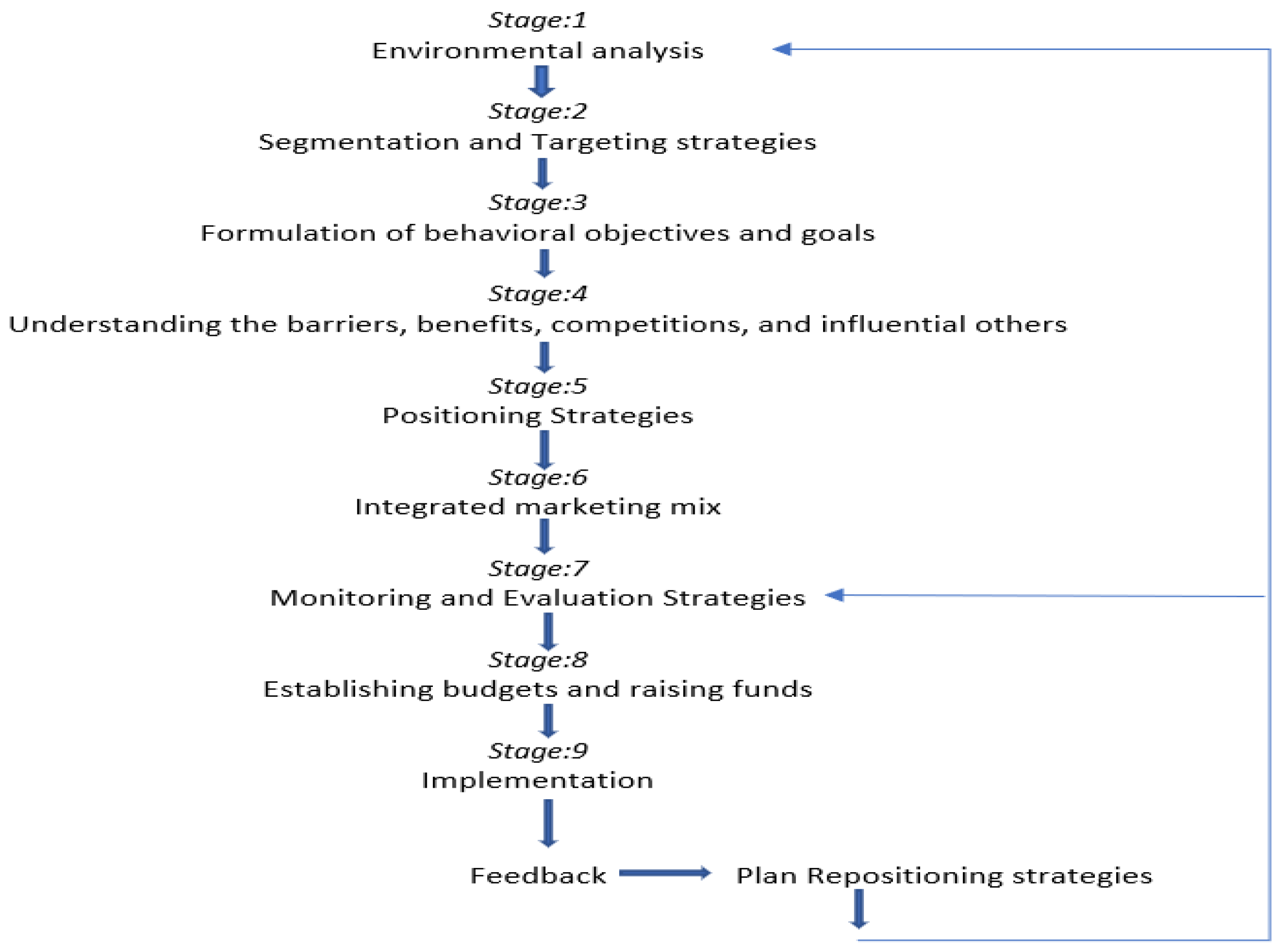

1.1. Stage 1: Environmental Analysis

1.2. Stage 2: Segmenting, Evaluating, and Targeting the Audience

1.3. Stage 3: Formulating Behavioral Objectives and Goals

1.4. Stage 4: Understanding the Barriers, Benefits, Competitions, and Influential Others

- (a).

- Increasing the benefit of target behavior: e.g., An appreciation certificate (if vaccinated) from a high-rank government official.

- (b).

- Decrease the target behavior’s barriers (and or expenses): e.g., Free pick and drop to vaccination camps and back to home.

- (c).

- Decrease the benefits of the competing behavior: e.g., Restricted supply of immunity booster drugs if not vaccinated.

- (d).

- Increase the barriers (and or expenses) of the competing behavior: e.g., Audience to pay a heavy price for immunity booster drugs if not vaccinated.

1.5. Stage 5: Crafting a Positioning Strategy

“We want the senior citizens to see COVID-19 vaccinations as a life vest to guard against coronavirus as more important and beneficial than abstinence”.

- (a).

- Behavior-focused positioning—How do we want the target audience to behave? (e.g., to take vaccine shots at the earliest to combat COVID infections)

- (b).

- Barrier-focused positioning—Focus on the social marketers offering to help overcome perceived barriers such as fear, self-efficacy, and perceived high cost associated with performing the desired behavior (e.g., free pick up and drop off to vaccination camps and back to home)

- (c).

- Benefits focused positioning—The focus here should be on the benefits that the target audience wants (e.g., free health checkup once a month if vaccinated).

- (d).

- Competition focused positioning—Focus on removing the competing behavior of the target audience (e.g., Positioning vaccine hesitancy as a severe threat to life).

1.6. Stage 6: Developing an Integrated Marketing Mix

1.7. Stage 7: Monitoring and Evaluation

1.8. Stage 8: Establishing Budgets and Raising Funds

1.9. Stage 9: Implementation Plan

2. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kashte, S.; Gulbake, A.; El-Amin, S.F.; Gupta, A. COVID-19 Vaccines: Rapid Development, Implications, Challenges and Future Prospects. Hum. Cell 2021, 34, 711–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, S.H. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: 12 Things You Need to Know. Available online: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus/covid19-vaccine-hesitancy-12-things-you-need-to-know (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- MacDonald, N.E.; Eskola, J.; Liang, X.; Chaudhuri, M.; Dube, E.; Gellin, B.; Goldstein, S.; Larson, H.; Manzo, M.L.; Reingold, A.; et al. Vaccine Hesitancy: Definition, Scope and Determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, H.J.; Jarrett, C.; Eckersberger, E.; Smith, D.M.D.; Paterson, P. Understanding Vaccine Hesitancy around Vaccines and Vaccination from a Global Perspective: A Systematic Review of Published Literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine 2014, 32, 2150–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, S.K. Social Media, Positive News Give Hope amid Pandemic in India. Media Asia 2021, 48, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M.C.; Rahal, C.; Brazel, D.; Yan, J.; Gieysztor, S. COVID-19 Vaccine Deployment: Behaviour, Ethics, Misinformation and Policy Strategies; The Royal Society & The British Academy: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Razai, M.S.; Chaudhry, U.A.R.; Doerholt, K.; Bauld, L.; Majeed, A. Covid-19 Vaccination Hesitancy. BMJ 2021, 373, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan Sharma India Administers Record 1.28 Crore COVID-19 Vaccine Doses in a Day. Available online: https://www.indiatoday.in/coronavirus-outbreak/story/india-1-crore-vaccinations-covid19-coronavirus-single-day-again-1847649-2021-08-31 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Shekhar, S.K.; Jose, T.P. COVID-19 and Second Wave: Can India Become Self-Sufficient in Vaccines? Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandoth, S.; Shekhar, S.K. Media and COVID-19 Vaccine Negligence in India. Media Asia 2021, 49, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Sujitha, P. Vaccine Hesitancy in India-the Challenges: A Review. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2020, 7, 4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachauli, C.; Bhan, A. Tackling Vaccine Hesitancy Challenge in Rural India. Available online: https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/science/tackling-vaccine-hesitancy-challenge-in-rural-india/article34994324.ece (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Lee, N.; Kotler, P. Influencing Behaviors for Good. In Social Marketing: Influencing Behaviors for Good; Sage: Newcastle, UK, 2008; pp. 2011–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Henley, N.; Raffin, S.; Caemmerer, B. The Application of Marketing Principles to a Social Marketing Campaign. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2011, 29, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opel, D.J.; Diekema, D.S.; Lee, N.R.; Marcuse, E.K. Social Marketing as a Strategy to Increase Immunization Rates. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2009, 163, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mallik, P. Is Vaccine Hesitancy Plaguing Rural India? Less Than 0.5%. Available online: https://thelogicalindian.com/health/is-vaccine-hesitancy-plaguing-rural-india-less-than-05-have-registered-28929 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Mandal, P.C. Marketing Realities in the New Environment. Int. J. Bus. Strateg. Autom. 2020, 1, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mose, A. Syaifuddin Analysis of Macro and Micro Environment on the Marketing Strategy Formulation and the Influence to the Competitive Advantage (Case Study). Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 15, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Manan, M. Sony Micro and Macro Environment. 2016. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/mahermanan27/sony-micro-and-macro-environment (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Wright, M. The Complete Guide to STP Marketing with Examples|Yieldify. Available online: https://www.yieldify.com/blog/stp-marketing-model/ (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Savciuc, O.; Timotin, A. The Integration of Behavioural Change Models in Social Marketing Programs in Public Health. Mark. Inf. Decis. J. 2019, 2, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanishka Gupta Jab Hesitancy: Vaccine Fear in Rural India a Challenge for Health Workers. Available online: https://www.business-standard.com/multimedia/video-gallery/coronavirus/jab-hesitancy-vaccine-fear-in-rural-india-a-challenge-for-health-workers-126599.htm (accessed on 3 October 2021).

- Andreasen, A.R. Marketing Social Marketing in the Social Change Marketplace. J. Public Policy Mark. 2002, 21, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, C. Difference between Differentiated Marketing Strategy & Concentrated Marketing Strategy|Your Business. Available online: https://yourbusiness.azcentral.com/difference-between-differentiated-marketing-strategy-concentrated-marketing-strategy-5962.html (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- McKenzie-Mohr, D. Fostering Sustainable Behavior through Community-Based Social Marketing. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cothran, H.M.; Wysocki, A.F. Developing SMART Goals for Your Organization. EDIS 2005, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, M. Midstream Social Marketing and the Co-Creation of Public Services. J. Soc. Mark. 2016, 6, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, A.; Trout, J. Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind; McGraw-Hill Prof.: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, R. Re-Thinking and Re-Tooling the Social Marketing Mix. Australas. Mark. J. 2012, 20, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.D.; Azzam, T.; Wanzer, D.L.; Skousen, D.; Knight, C.; Sabarre, N. Enhancing the Effectiveness of Logic Models. Am. J. Eval. 2020, 41, 452–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, E.; Couper, M.P. Some Methodological Uses of Responses to Open Questions and Other Verbatim Comments in Quantitative Surveys. Methods Data Anal. 2017, 11, 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, M.R.; Kostyk, A.; Zhou, W.; Paas, L. Novel Approaches for Improving Data Quality from Self-Administered Questionnaires. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 61, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, H. The Logic of Qualitative Survey Research and Its Position in the Field of Social Research Methods. Forum Qual. Sozialforsch. 2010, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muijeen, K.; Kongvattananon, P.; Somprasert, C. The Key Success Factors in Focus Group Discussions with the Elderly for Novice Researchers: A Review. J. Heal. Res. 2020, 34, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Woods Johnson Fundation RWJF—Qualitative Research Guidelines Project|Informal Interviews|Informal Interviewing. Available online: qualres.org/HomeInfo-3631.html (accessed on 17 April 2022).

- Morgan, S.J.; Pullon, S.R.H.; MacDonald, L.M.; McKinlay, E.M.; Gray, B.V. Case Study Observational Research: A Framework for Conducting Case Study Research Where Observation Data Are the Focus. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Marketing Management/Philip Kotler, Kevin Lane Keller; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, G.; Adam, S.; Denize, S.; Kotler, P. Principles of Marketing, 11th ed.; Pearson Australia: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Sr.No | Criteria | Details | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Segment | Number of people in this segment | How many senior citizens are yet to take the COVID-19 vaccine? |

| 2. | Problem incidence | Number of people engaged in problem-related behavior | What percentage of senior citizens are reluctant to take the COVID-19 vaccines? |

| 3. | Problem severity | The level of consequences of problem-related behavior in this segment | What is the incidence of COVID-19 infections among senior citizens? |

| 4. | Defenselessness | The number of people who can take care of themselves versus those needing help | What percentage of senior citizens have easy access to vaccination camps? |

| 5. | Reachability | The extent to which this audience can be identified and reached. | Are there media channels and other options that can be used for promoting vaccination messages targeted explicitly for senior citizens? |

| 6. | General responsiveness | The readiness, willingness, and ableness to respond to the social marketer | How concerned are senior citizens with COVID-19 infections? How do they compare with Generation Y? Which group has been responsive to similar campaigns in the past? |

| 7. | Incremental costs | Estimated cost to reach and influence this segment | Are there free or inexpensive channels to reach the target audience? How does this compare to Generation Y? Are there similar campaigns from neighboring states that have worked well with senior citizens, or will the social marketer need to start from scratch? |

| 8. | Marketing mix | The likeliness of this segment to respond to social marketing strategies | What are the most significant influences on senior citizens’ decisions relative to their vaccine hesitancy? How concerned are their relatives with potential programs and messages? |

| 9. | Organisational capabilities | Availability of staff expertise to handle the social issue | Are the social marketers’ experience and knowledge in handling senior citizens as strong as Generation Y? |

| Purpose | Behavior | Knowledge | Belief |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduce vaccine hesitancy | What does the social marketer want the target audience to do? | What does the target audience need to know before they act? | What does the target audience need to believe before they act? |

| Objective | Get vaccinated | To know that vaccinated people have fewer complications if affected with COVID-19 | Believing that postponing vaccination can risk one’s health and deteriorate nation’s health index |

| Target goal | Increase the percentage (from 20% to 70% in 3 months) of senior citizens who take vaccination | Increase the percentage of people (from 20% to 70% in 3 months) who become aware of the fact that vaccination brings fewer complications | Increase the percentage of people (from 20% to 70% in 3 months) who believe that postponing vaccination is a risk to one’s health and nation’s health. |

| SMART | Details | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Specific | Goals need to be and clearly defined. The marketer must know what to accomplish | To educate the senior citizens in rural India to get vaccinated |

| Measurable | The goal set to be achieved. How can it be assured that the goal will be completed? | The marketer may request the audience to furnish the vaccination certificate provided by the COWIN * app/web portal. The social marketing firm may seek the help of the government to capture this measurement. The report may furnish the list of people who are getting vaccinated after the campaign |

| Attainable | Goals to be realistic. The social marketer may scrutinize what is possible with the availability of resources, time, and knowledge. The marketer must ascertain the likelihood of the campaign being successful | How likely were the senior citizens’ responses to similar marketing campaigns in the past |

| Realistic | The importance of creating a material impact on achieving the objectives | To examine if the target audience is ready to listen to the marketer. Do they want to be physically fit and stay immune? |

| Time-based | Locking the goals to a specific time frame | The marketer can lock the target to be achieved, such as few months |

| 4Ps | Description | Strategies for Targeting Senior Citizens |

|---|---|---|

| Product | ||

| Core | Benefits of performing the behavior | By taking vaccine: Peace of mind. Stay protected |

| Actual | Special features | Vaccination camps |

| Augmented | Additional features put forward to perform the behavior | Counseling, support at home |

| Price | Monetary and non-monetary incentives/ disincentives |

|

| Place | Access to the goods and services |

|

| Promotion | Key messages | “All vaccination services are free.” “Vaccination for everyone is prevention for all.” “Privileges for vaccinated senior citizens” |

| Key messengers | Health care workers Social marketers Government ASHA * workers Community volunteers NGOs | |

| Key media channels | Mass media: TV, radio, print media, internet, hoardings/billboards, wall painting, bus/auto panels, LED scrolls Print materials: Posters, pamphlets, factsheets, banners Special events: Flashmobs, street plays, drama, local folk songs, story telling Videos: At health center waiting areas, banks, public library Personal communications: Use of health workers and peer groups Community mobilisation: Use of surveillance groups Advocacy: Local teams targeting families and political leaders |

| Input | Output | Outcome | Impact | ROI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resources allocated to the social marketing campaign | Activities conducted to influence the behavior of the audience | Response to output by the target audience | Indicators showing the level of impact on the social issue | Rate of return associated with the effort |

| Money, Social marketers, Man-hours, Existing material used | The number of senior citizens targeted/met, Events (camps) held, Reach and frequency of social marketing communications, Media coverage (free and paid), Implementation of the social marketing programs (Whether conducted on time, budget, etc.) | Change in behavior, belief, and value of the senior citizens, No. of vaccinations completed, Response to the social marketing campaign, Campaign awareness etc. | Improvement in health, Lives saved | Cost to change the behavior, For every money spent, money saved or generated calculating ROI |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shekhar, S.K. Social Marketing Plan to Decrease the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Senior Citizens in Rural India. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7561. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137561

Shekhar SK. Social Marketing Plan to Decrease the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Senior Citizens in Rural India. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):7561. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137561

Chicago/Turabian StyleShekhar, Suraj Kushe. 2022. "Social Marketing Plan to Decrease the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Senior Citizens in Rural India" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 7561. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137561

APA StyleShekhar, S. K. (2022). Social Marketing Plan to Decrease the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Senior Citizens in Rural India. Sustainability, 14(13), 7561. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137561