Trust Transfer in Sharing Accommodation: The Moderating Role of Privacy Concerns

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Institutional Trust and Sharing Accommodation

2.2. Trust Transfer

2.3. Privacy Concerns and Sharing Accommodation

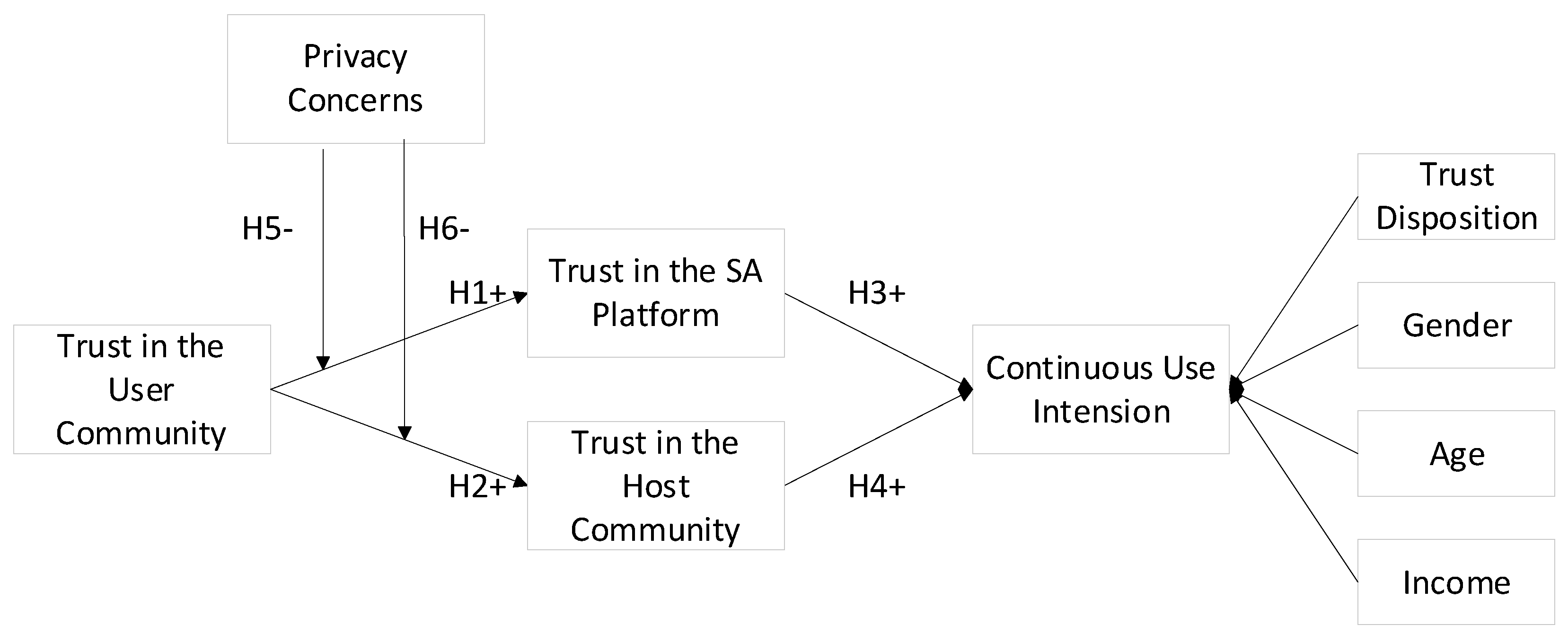

3. Research Model and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Trust Transfer

3.2. Institutional Trust and Continuous Use Intention

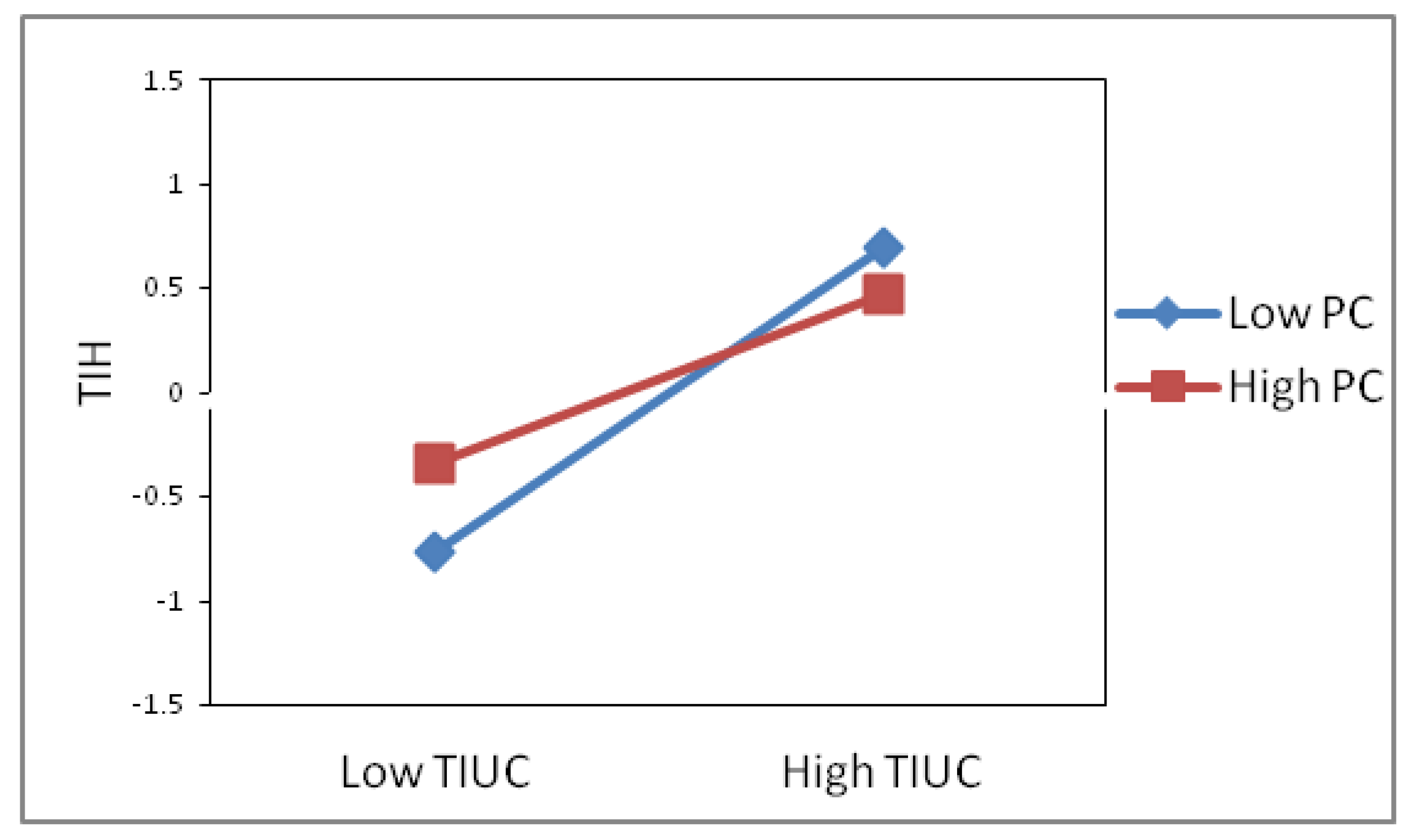

3.3. Moderating Effects of Privacy Concerns

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Measurement Development

4.2. Sample and Data Collection

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Measurement Model

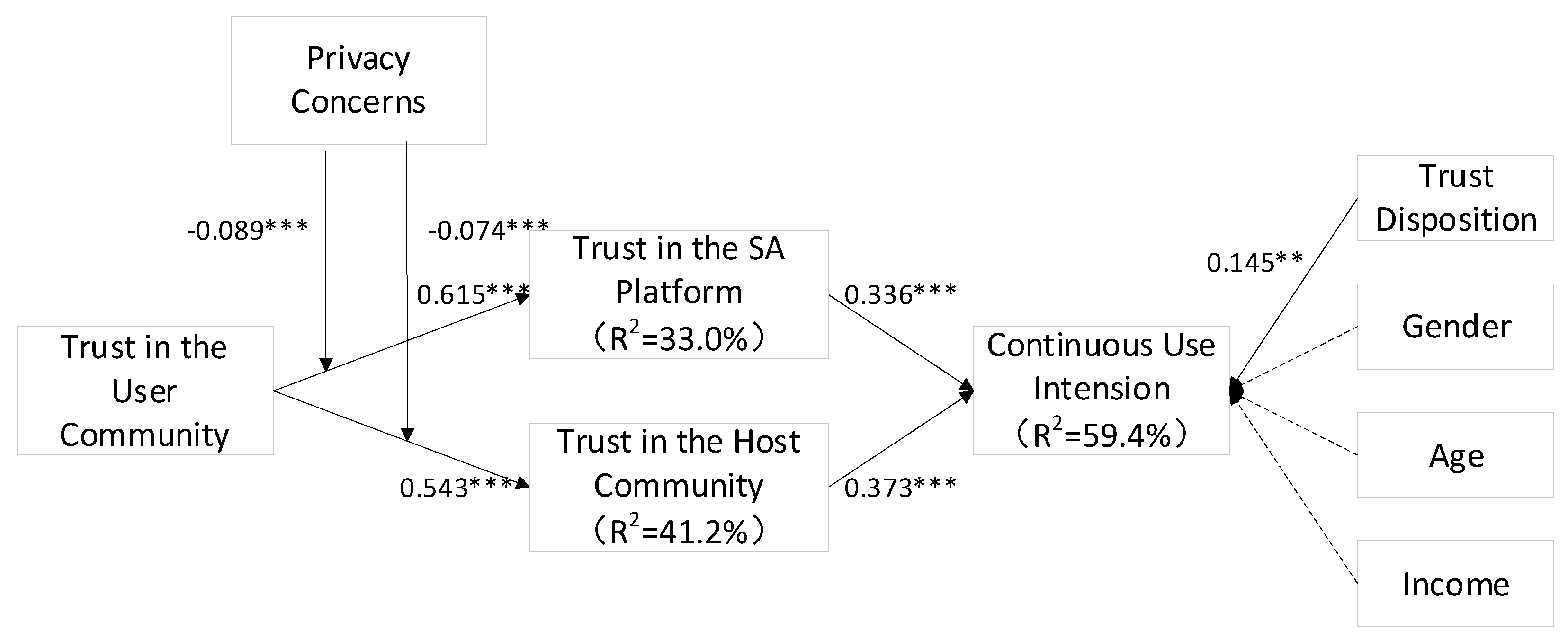

5.2. Structural Model

6. Conclusions and Discussion

6.1. Research Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs | Code | Measurement Items | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trust in the SA platform | TIP1 | The platform is honest. | Yang et al., 2019 [42] |

| TIP2 | The platform is trustworthy. | ||

| TIP3 | The platform knows how to provide an excellent online booking accommodation service. | ||

| Continuous Use Intention | CUI1 | I will continue to use the platform to book rooms. | Gefen & Straub, 2004 [43] |

| CUI2 | In the short term, I will continue to use the platform to book rooms. | ||

| CUI3 | In the long term, I will continue to use the platform to book rooms. | ||

| Trust in the host community | TIH1 | I am confident most hosts on the platform are reliable. | Pavlou & Gefen, 2004 [5] |

| TIH2 | I am confident most hosts on the platform are trustworthy. | ||

| TIH3 | The hosts on the platform can provide good service. | ||

| Trust in the User Community | TIUC1 | Other users of the platform are willing to genuinely help me, such as providing real feedback and answering my questions. | Söllner et al., 2016 [16] |

| TIUC2 | Other users of the platform are truthful in dealing with one another | ||

| TIUC3 | The information provided by other users in the comment area is worth considering. | ||

| Privacy Concerns | PC1 | I am concerned that the information I submit to platforms and online hosts could be compromised. | Dinev & Hart, 2006 [20] |

| PC2 | I am concerned that the information I submit to platforms and online hosts could be misused. | ||

| PC3 | I am concerned that the information submitted to the platform and the host may be used by others. | ||

| Trust Disposition | TD1 | I generally trust other people. | Gefen & Straub, 2004 [43] |

| TD2 | I generally have faith in humanity. | ||

| TD3 | I feel that people are generally trustworthy |

References

- Ling, C.; Zhang, Z. Research on the development path of “sharing economy” in China: Based on online short-term rental. Mod. Manag. Sci. 2014, 10, 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Economic View. Available online: https://mo.mbd.baidu.com/r/F7cfZa3DnG?f=cp&u=229bd0cc6b46bad3 (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- City Report. Available online: https://m.weibo.cn/1708877153/4619828222498256 (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Fang, Y.; Qureshi, I.; Sun, H.; McCole, P. Trust, satisfaction, and Online Repurchase: The Moderating Role of Perceived Effectiveness of E-commerce Institutional Mechanisms. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 407–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Park, S. When guests trust hosts for their words: Host description and trust in sharing economy. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J. A Study of the Multilevel and Dynamic Nature of Trust in E-Commerce from a Cross-Stage Perspective. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2014, 19, 11–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Gefen, D. Building Effective Online Marketplaces with Institution-Based Trust. Inf. Syst. Res. 2004, 15, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, B.; Zeng, Q.; Fan, W. Examining macro-sources of institution-based trust in social commerce marketplaces: An empirical study. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2016, 20, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, B. Exploring the moderators and causal process of trust transfer in online-to-offline commerce. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 98, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, H.; Bock, G. Trust transference in brick and click retailers: An investigation of the before-online-visit phase. Inf. Manag. 2007, 44, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester Research. North American Technographics Media and Marketing Online Survey; Forrester Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Heijden, H.; Verhagen, T.; Creemers, M. Understanding online purchase intentions: Contributions from technology and trust perspectives. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2003, 12, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, Q.; Davison, R.M.; Hua, Z. What Drives Trust Transfer? The Moderating Roles of Seller-Specific and General Institutional Mechanisms. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2015, 20, 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, G.R.; Boza, M. Trust and concern in consumers’ perceptions of marketing information management practices. J. Interact. Mark. 1999, 13, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddei, S.; Contena, B. Privacy, trust and control: Which relationships with online self-disclosure? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Cummings, L.L.; Chervany, N.L. Initial Trust Formation in New Organizational Relationships. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mao, Z.E.; Jones, M.F.; Li, M.; Wei, W.; Lyu, J. Sleeping in a stranger’s home: A trust formation model for Airbnb. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Zhang, T.; Wang, L.; Keller, L.R. Trust Antecedents, Trust and Online Microsourcing Adoption: An Empirical Study from the Resource Perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 85, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsai, T.; Wang, W.; Lin, Y.; Choub, S. An O2O Commerce Service Framework and its Effectiveness Analysis with Application to Proximity Commerce. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 3498–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Söllner, M.; Hoffmann, A.; Leimeister, J.M. Why different trust relationships matter for information systems users. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2016, 25, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benlian, A.; Titah, R.; Hess, T. Differential Effects of Provider Recommendations and Consumer Reviews in E-Commerce Transactions: An Experimental Study. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 237–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.J. Trust Transfer on the World Wide Web. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Huang, J.; Su, S. The effects of trust on consumers’ continuous purchase intentions in C2C social commerce: A trust transfer perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, T.; Hart, P. An Extended Privacy Calculus Model for E-Commerce Transactions. Inf. Syst. Res. 2006, 17, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Data Protection Regulation(GDPR). Available online: https://gdpr-info.eu (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Pavlou, P.A. State of the information privacy literature: Where are we now and where should we go? MIS Q. 2011, 35, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Park, J.; Jung, Y. The role of privacy fatigue in online privacy behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 81, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Milberg, S.J.; Burke, S.J. Information Privacy: Measuring Individuals’ Concerns About Organizational Practices. MIS Q. 1996, 20, 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Agarwal, J. Internet Users’ Information Privacy Concerns (IUIPC): The Construct, the Scale, and a Causal Model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2004, 15, 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, H.J.; Dinev, T.; Xu, H. Information privacy research: An interdisciplinary review. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 989–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lutz, C.; Hoffmann, C.P.; Bucher, E.; Fieseler, C. The role of privacy concerns in the sharing economy. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2018, 21, 1472–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teubner, T.; Flath, C.M. Privacy in the Sharing Economy. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2019, 20, 213–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joinson, A.N.; Reips, U.; Buchanan, T.; Schofield, C.B.P. Privacy, trust, and self-disclosure online. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2010, 25, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCole, P.; Ramsey, E.; Williams, J. Trust considerations on attitudes towards online purchasing: The moderating effect of privacy and security concerns. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1018–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranzini, G.; Etter, M.; Vermeulen, I. European Perspectives on Privacy in the Sharing Economy. 2017. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3048152 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Pan, Y.; Wu, D.; Olson, D.L. Online to offline (O2O) service recommendation method based on multi-dimensional similarity measurement. Decis. Support Syst. 2017, 103, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, T.; Benkenstein, M. When good WOM hurts and bad WOM gains: The effect of untrustworthy online reviews. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5993–6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Chervany, N.L. What Trust Means in E-Commerce Customer Relationships: An Interdisciplinary Conceptual Typology. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2001, 6, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.J.; Sheu, C. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsón Ponte, E.; Carvajal-Trujillo, E.; Escobar-Rodríguez, T. Influence of trust and perceived value on the intention to purchase travel online: Integrating the effects of assurance on trust antecedents. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Ferrin, D.L.; Rao, H.R. Trust and Satisfaction, Two Stepping Stones for Successful E-Commerce Relationships: A Longitudinal Exploration. Inf. Syst. Res. 2009, 20, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gefen, D.; Pavlou, P.A. The Boundaries of Trust and Risk: The Quadratic Moderating Role of Institutional Structures. Inf. Syst. Res. 2012, 23, 940–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.J.; Choi, H.C.; Joppe, M. Exploring the relationship between satisfaction, trust and switching intention, repurchase intention in the context of Airbnb. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.W.Y.; Chan, T.K.H.; Balaji, M.S.; Chong, A.Y. Why people participate in the sharing economy: An empirical investigation of Uber. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 829–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, G.; Zahedi, F.M.; Gefen, D. The role of privacy assurance mechanisms in building trust and the moderating role of privacy concern. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 624–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Qin, L.; Kim, Y.; Hsu, J. Impact of privacy concern in social networking web sites. Internet Res. 2012, 22, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J. Central or peripheral? Cognition elaboration cues’ effect on users’ continuance intention of mobile health applications in the developing markets. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 116, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, C.; Huang, H.; Xu, W. Research on User Continuance Intention of Mobile Map Applications From the Perspective of Privacy Concern. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 5, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Lee, K.; Lee, H.; Koo, C. In Airbnb we trust: Understanding consumers’ trust-attachment building mechanisms in the sharing economy. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.W. Consumer trust in B2C e-Commerce and the importance of social presence: Experiments in e-Products and e-Services. Omega 2004, 32, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How Meituan Homestay Makes It into the Top Three in the Homestay Industry in the Last Two and Half Years. Available online: http://www.woshipm.com/evaluating/3099274.html (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- The Research Report on the Development of China’s Homestay Industry. Available online: https://www.docin.com/p-2578869341.html (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Liang, H.; Xue, Y. Understanding and Mitigating Uncertainty in Online Exchange Relationships: A Principal-Agent Perspective. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 105–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A Partial Least Squares Latent Variable Modeling Approach for Measuring Interaction Effects: Results from a Monte Carlo Simulation Study and an Electronic-Mail Emotion/Adoption Study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKnight, D.H.; Choudhury, V.; Kacmar, C. Developing and Validating Trust Measures for e-Commerce: An Integrative Typology. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 334–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S. Platform-based mechanisms, institutional trust, and continuous use intention: The moderating role of perceived effectiveness of sharing economy institutional mechanisms. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shen, J. A Study on Airbnb’s Trust Mechanism and the Effects of Cultural Values—Based on a Survey of Chinese Consumers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, M.; Qin, J.; Wen, M.; Chen, W. Sustaining Consumer Trust and Continuance Intention by Institutional Mechanisms: An Empirical Survey of DiDi in China. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 158185–158203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, N.W.; Ruangkanjanases, A.; Chen, S. The Effects of Product Monetary Value, Product Evaluation Cost, and Customer Enjoyment on Customer Intention to Purchase and Reuse Vendors: Institutional Trust-Based Mechanisms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Zhang, K.Z.K.; Chen, C.; Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, M.K.O. What drives trust transfer from web to mobile payment services? The dual effects of perceived entitativity. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Accept,

Accept,  Reject.

Reject.

| Measure | Items | Valid Response (n = 470) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | ||

| Gender | Male | 282 | 60.00% |

| Female | 188 | 40.00% | |

| Age | 18 or below | 3 | 0.64% |

| >18 and ≤25 | 118 | 25.11% | |

| >25 and ≤30 | 231 | 49.14% | |

| >30 and ≤35 | 79 | 16.81% | |

| >35 | 39 | 8.30% | |

| Education | High school and below | 48 | 10.21% |

| Bachelor and college degree | 401 | 85.32% | |

| Graduate and above | 21 | 4.47% | |

| Income per month (RMB) | ≤2000 | 46 | 9.79% |

| >2000 and ≤4000 | 133 | 28.30% | |

| >4000 and ≤8000 | 265 | 56.38% | |

| >8000 | 26 | 5.53% | |

| Frequency of using | Once every two Months | 233 | 49.57% |

| Once a Month | 169 | 35.96% | |

| Two to three times a Month | 58 | 12.34% | |

| More than four times (including four) a Month | 10 | 2.13% | |

| Platforms | Meituan Homestay | 254 | 54.04% |

| Tujia | 131 | 45.96% | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust in the SA platform | 1 | 0.876 | |||||

| Continuous use intention | 2 | 0.673 | 0.839 | ||||

| Trust in the host community | 3 | 0.626 | 0.650 | 0.873 | |||

| Trust in the user community | 4 | 0.552 | 0.507 | 0.615 | 0.871 | ||

| Privacy concerns | 5 | 0.133 | 0.158 | 0.079 | 0.120 | 0.902 | |

| Trust disposition | 6 | 0.624 | 0.560 | 0.548 | 0.468 | 0.032 | 0.875 |

| Variable | Items | Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust in the SA platform | TIP1 | 0.886 | 0.848 | 0.908 | 0.768 |

| TIP2 | 0.889 | ||||

| TIP3 | 0.853 | ||||

| Continuous use intention | CUI1 | 0.884 | 0.789 | 0.877 | 0.704 |

| CUI2 | 0.827 | ||||

| CUI3 | 0.805 | ||||

| Trust in the host community | TIH1 | 0.884 | 0.844 | 0.906 | 0.762 |

| TIH2 | 0.878 | ||||

| TIH3 | 0.856 | ||||

| Trust in the user community | TIUC1 | 0.886 | 0.841 | 0.904 | 0.759 |

| TIUC2 | 0.852 | ||||

| TIUC3 | 0.875 | ||||

| Privacy concerns | PC1 | 0.965 | 0.901 | 0.929 | 0.814 |

| PC2 | 0.906 | ||||

| PC3 | 0.831 | ||||

| Trust disposition | TD1 | 0.878 | 0.846 | 0.907 | 0.765 |

| TD2 | 0.883 | ||||

| TD3 | 0.862 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust in the SA platform | 1 | ||||||

| Continuous use intention | 2 | 0.820 | |||||

| Trust in the host community | 3 | 0.739 | 0.796 | ||||

| Trust in the user community | 4 | 0.651 | 0.620 | 0.729 | |||

| Privacy concerns | 5 | 0.124 | 0.153 | 0.084 | 0.108 | ||

| Trust disposition | 6 | 0.734 | 0.684 | 0.646 | 0.554 | 0.058 |

| Constructs | Items | CUI | PC | TD | TIUC | TIH | TIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Use Intention | CUI1 | 0.884 | 0.229 | 0.500 | 0.462 | 0.568 | 0.610 |

| CUI2 | 0.827 | 0.135 | 0.445 | 0.455 | 0.552 | 0.566 | |

| CUI3 | 0.805 | 0.020 | 0.464 | 0.354 | 0.514 | 0.513 | |

| Privacy Concerns | PC1 | 0.193 | 0.965 | 0.062 | 0.162 | 0.093 | 0.161 |

| PC2 | 0.101 | 0.906 | 0.001 | 0.07 | 0.071 | 0.085 | |

| PC3 | 0.049 | 0.831 | −0.048 | −0.015 | −0.018 | 0.054 | |

| Trust Disposition | TD1 | 0.491 | 0.089 | 0.878 | 0.410 | 0.489 | 0.576 |

| TD2 | 0.516 | −0.005 | 0.883 | 0.436 | 0.517 | 0.542 | |

| TD3 | 0.460 | 0.001 | 0.862 | 0.380 | 0.427 | 0.518 | |

| Trust in the host community | TIH1 | 0.567 | 0.074 | 0.499 | 0.591 | 0.884 | 0.566 |

| TIH2 | 0.566 | 0.055 | 0.502 | 0.510 | 0.878 | 0.517 | |

| TIH3 | 0.569 | 0.078 | 0.433 | 0.507 | 0.856 | 0.556 | |

| Trust in the User Community | TIUC1 | 0.471 | 0.155 | 0.398 | 0.886 | 0.531 | 0.491 |

| TIUC2 | 0.412 | 0.037 | 0.417 | 0.852 | 0.546 | 0.445 | |

| TIUC3 | 0.442 | 0.120 | 0.409 | 0.875 | 0.531 | 0.505 | |

| Trust in the SA platform | TIP1 | 0.602 | 0.164 | 0.578 | 0.522 | 0.563 | 0.886 |

| TIP2 | 0.607 | 0.096 | 0.581 | 0.464 | 0.560 | 0.889 | |

| TIP3 | 0.558 | 0.087 | 0.476 | 0.461 | 0.522 | 0.853 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, B.; Wang, Z. Trust Transfer in Sharing Accommodation: The Moderating Role of Privacy Concerns. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127384

Lu B, Wang Z. Trust Transfer in Sharing Accommodation: The Moderating Role of Privacy Concerns. Sustainability. 2022; 14(12):7384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127384

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Baozhou, and Zhenhua Wang. 2022. "Trust Transfer in Sharing Accommodation: The Moderating Role of Privacy Concerns" Sustainability 14, no. 12: 7384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127384

APA StyleLu, B., & Wang, Z. (2022). Trust Transfer in Sharing Accommodation: The Moderating Role of Privacy Concerns. Sustainability, 14(12), 7384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127384