Abstract

Institutional systems have a crucial impact on the development of biotechnology. In this article, we analyze the interaction between biotechnology and institutions. To conduct our analysis, we use the case study method and the stakeholder perspective. Our findings suggest the following: (1) Through the analysis of patent data, biotechnology has been developing very rapidly in recent years in China; (2) basic biotechnology institutions have been established, consisting of government, policy, and other institutional arrangements; (3) the interaction between the development of biotechnology and its existing institutions is dynamic; and (4) the interaction is affected by relative stakeholders. This study contributes to the theory concerning the governance of biotechnology, which is important in the sustainable development of biotechnology. Moreover, the article sheds light on policy implications.

1. Introduction

As an enabling technology [1], biotechnology can be applied broadly, which is very important for the economy, society, and environment [2]. Particularly, the discoveries, invention, and application of biotechnologies are leading to the emergence of the bioeconomy [3,4,5]. Nevertheless, recent biotechnologies have increasingly generated practical issues and regulatory challenges [6,7,8]. The misuse of biotechnology could be harmful to the environment or biodiversity, and concerns have been raised concerning the uncertainty of people’s health, ethical issues, biosecurity, etc. [9]. At the end of 2018, the Chinese scientist Jian-Kui He claimed that he had helped create the world’s first genome-edited babies using the CRISPR–Cas9 tool, and this raised global discussion [10,11,12]. At present, it is not clear what will happen to the two genome-edited babies, but what is known is that the scientist was sentenced to prison for 3 years [13]. Generally, the development of biotechnology and bioeconomy require the establishment and improvement of a regulatory framework [3].

In addition to practice, the development of biotechnology has received broad interest among researchers [6,9,14,15]. Prior studies have noted the importance of biotechnology-related institutions in various aspects [9,16,17,18,19], particularly in promoting the development of biotechnology [20]. However, together with the development of biotechnology, the related institutions also change dynamically. Although biotechnology potentially generates great benefits, the cost implications under certain circumstances might be massive, leading to public controversies and the need for intervention by institutions [9]. The relationship, particularly the interaction mechanism between biotechnology and institutions, is underexplored. Therefore, we ask the following research question: What is the interaction mechanism between biotechnology development and its institutions?

To answer our research question, we select China as a research context. China, as an emerging developing nation, with the aim of overtaking the curve, has achieved some improvements in the field of biotechnology [14]. In those years, China has paid considerable attention to the development of the biotechnology industry [21]. In 2001, the biotechnology industry was listed as a high-tech industry in the 10th Five-Year Plan of High-tech Industry Development. In the Mid-Long Term S&T Development Plan (2006–2020), biotechnology is listed as the first of the eight types of cutting-edge technologies. The development of biotechnology in China has been very rapid in recent years. In accordance with the latest statistics by the OECD (key biotechnology indicators, available online: https://www.oecd.org/sti/emerging-tech/keybiotechnologyindicators.htm (accessed on 10 March 2022)), in 2018, China accounted for 8.2% of biotechnology patents from the IP5 patent families (the five largest IP offices in the world, including the European Patent Office (EPO), the Japan Patent Office (JPO), the Korean Intellectual Property Office (KIPO), the National Intellectual Property Administration of the People’s Republic of China (CNIPA), and the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO)) only after the US (37.6%) and Japan (12.3%), while the percentage was only 0.8% in 2001. However, the institution that regulates and promotes the development of biotechnology is not established at first, and experiences a process to improve. This situation provides a proper foundation to examine our research question in China’s context.

The reminder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we analyze the existing research on this topic. In Section 3, we introduce the research design. In Section 4, we present the situation of the biotechnology and relative institution. In Section 5, we analyze the role of stakeholders in the relationship between biotechnology and institutions. In Section 6, we present the main findings. Finally, Section 7 concludes our study.

2. Existing Research

2.1. Biotechnology and Institutions

Existing research on the relationship between technology and institutions increasingly focuses on the effects of institutions on technology [15,16,18,22]. The effects are mainly reflected in the following aspects. First, institutions stimulate and promote the research and development (R&D) of technology, and most countries in the world have put forward policies to support R&D activity [15,23]. Bronzini and Piselli [16] studied the impact of an R&D subsidy program on firm innovation, and found that the program had a significant impact on the number of patent applications. Second, institutions help protect technology and promote the commercialization of technology. The patent institution plays a crucial role [17]. In this case, Henderson et al. [18] found that the implementation of the Bayh-Dole Act has increased the extent of patent licensing.

In the field of biotechnology, OECD provides a framework for the function of policies, including supporting research, diffusing knowledge and expertise, commercializing biotechnology research, and encouraging the adoption (application and use) of biotechnology [19]. However, institutions also regulate R&D, and the commercialization of technology. This is mainly due to the fact that the use of biotechnology may pose risks to public health or the balance of the environment [9,22]. In the literature, Wiktorowicz and Deber [9] presented a political model for biotechnology regulation. Moreover, Stewart and Knight [22] studied the history of agricultural biotechnology regulatory policy in the US since 1972.

In addition, technology development pushes institutional change [24]. Evolution economist Nelson [25] analyzes the coevolution of technology and institutions in one of his early papers. With the development of technology, institutions may evolve at the same time, and this is particularly evident in the patent protection of biotechnology, since patentability for biotechnology in patent law has been revised in many countries. The development and application of biotechnology affects and is affected by a variety of stakeholders, and the institutions related to biotechnology are established in a system consisting of those stakeholders. We identify four types of key stakeholders in the relationship between biotechnology and institutions. The first is the government, which plays a central role in the institutional system and bioeconomy [26]. Governments intervene in the development and application of biotechnology by making policies, and taking institutional actions. The second is the industry, which acts as the link where technology is changed to be directly helpful in the development of the economy. The bioeconomy consists of industries that rely on biotechnologies [3]. The biotechnology industry is stressed by governments not only due to the fact that it is necessary for the health of humans, but also due to the high profit from innovations. The third is the university and public research institute (U & PRI), which is a main producer of biotechnology. The fourth is consumers. Even though consumers do not have direct impact on biotechnology, they are greatly influenced by biotechnology, and they are cared for by the government when making policies.

Institution helps in reducing uncertainty. Therefore, organizations make rational choices by considering institutional factors, such as the state and society when making and implementing strategies [27,28], and this is how institutions influence the behavior of organizations [29]. At the same time, in the long run, institutions motivated by internal and external forces can also be affected and will change, as well [30]. In the field of biotechnology, different types of organizations are involved, and we combine the perspective of institutions and stakeholders to consider the more complicated interactions.

2.2. Stakeholder Perspective

In this study, we use a stakeholder perspective to analyze the relationship between biotechnology and institutions. Freeman’s [31] seminal research on stakeholders promoted scholars’ attention in this area. Since then, stakeholder theory has experienced an explosion of theoretical development over the past several years in one way or another [32], and has been broadly used in the literature [33,34,35,36]. Among these articles, the studies on policy [32,37], institution [38], and governance [39] are similar to the topic of the present research.

Carroll [40] defined stakeholder as “any individual or group who can affect or is affected by the actions, decisions, policies, practices, or goals of the organization”. Donaldson and Preston [41] divided stakeholder theory into research of the “facts” (empirical description and summary) and “value” (normative core). Analysis based on the stakeholder perspective is required to consider the interests and concerns of different groups and individuals [32]. In solving the question in this research, both “facts” and “value” are stressed, since we care not only about the present relationship between biotechnology and institutions (“facts”), but also what the relationship should be (“value”).

In our research, the interaction between biotechnology and institutions is a dynamic process, and is affected by various groups and individuals. At the same time, in a bioeconomy, the engagement of key stakeholders in the governance is an important theme to be stressed [7]. Therefore, the stakeholder perspective is particularly suitable here.

3. Research Design

3.1. Case Study

The case study method allows for the investigation of phenomena in their general complexity [42]. In addition, it is effective for research on a topic where the main aim is to find an answer to “what” and ‘‘how’’ questions [43]. The stakeholder theory provides a perspective and tool to understand the relationship between biotechnology and institutions, yet the relationship should be based on practice and evidence. Therefore, we select practical cases to explain the relationship.

In this analysis, three cases are selected. The first is the discussion of genetically modified food in China; the second is the “gene-edited babies” event in China; and the third is the development of vaccines and detection technology for COVID-19 in China. The three cases are used since (1) each of them is relevant to the development and application of biotechnology, and is closely related to institutions; (2) each of them is broadly considered in China.

3.2. Data Collection

3.2.1. Patent Data

We use patent application information to indicate the development of biotechnology. Patent is a frequent indicator used to measure technological innovation. Ahuja and Katila [44] use the number of granted patents to measure firms’ innovation performance, and Carree et al. [45] use the number of patent applications per capita to measure regional innovation. In the field of biotechnology, patents are intensively used to protect inventions, and patent indicators can shed light on the level of biotechnology activity [2]. In accordance with a report by OECD [46], biotechnology patents represented 6.5% of countries’ patent portfolios on average from 2004 to 2006.

The biotechnology-related patents are identified in Table 1, which is suggested by the OECD [47]. We obtain access to patent data through the database of Patyee (available online: patyee.com (accessed on 27 March 2022)), a broadly used commercial patent database in China, whose original patent data is extracted from the official patent database of the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPO). We search data from 1985 to present (27 March 2022), and obtain 575,490 biotechnology patent application records in total. However, considering the time lag between patent application and publication, there is an underestimation of the exact number, since some recently submitted applications have not been disclosed.

Table 1.

IPC codes of biotechnology patents.

3.2.2. Case Information

The information for our case analysis is collected mainly from second-hand materials. These materials include: (1) Policy documents published by governments; (2) newspaper articles published by various newspapers in China; (3) books and journal publications; and (4) other online materials, e.g., announcements published by governments on their websites. Most of these materials are official publications or academic publications, and in the process of analysis, we use information from various sources to conduct mutual verification. Therefore, the information collected for case analysis is credible.

4. The Biotechnology and Relative Institutions

4.1. The Development of Biotechnology in China

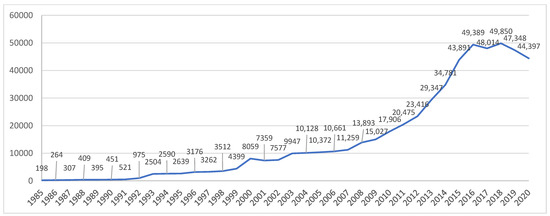

Figure 1 shows the number of biotechnology patents in China during 1985–2020. Considering the time lag between patent application and publication, the numbers in 2021 and 2022 are not displayed. The number of biotechnology patents in 1985 was 198, and it reached 7359 in 2001, increasing by 36 times. In the 21st century, the number of biotechnology patents experienced an even sharper increase, rising to 49,850 in 2018.

Figure 1.

Number of biotechnology patents in China (1985–2016).

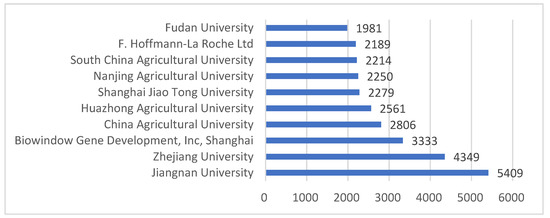

Figure 2 shows the 10 organizations with the most biotechnology patents in China. Jiangnan University ranks first with 5409 biotechnology patents. Among the top 10 applicants, there are only two companies: Biowindow Gene Development Inc. (Shanghai, China) in Shanghai ranks third with 3333 applications; the other is F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland, ranking ninth with 2189 applications. The remaining organizations are all domestic universities.

Figure 2.

Main applicants of the biotechnology patents in China.

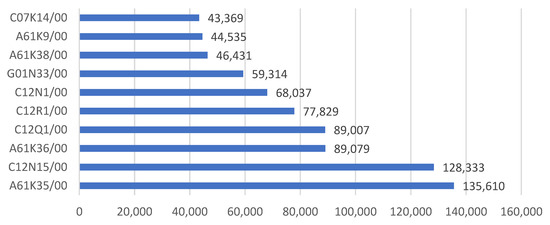

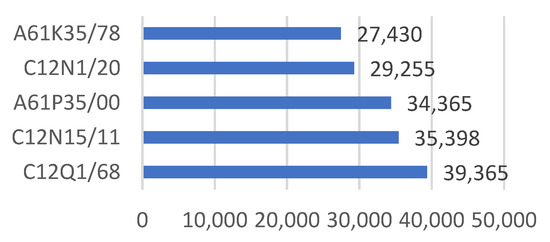

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the main IPC codes of biotechnology patents in China. Most of the biotechnology patents fall into the area of the class of A61K35 (medicinal preparations containing materials or reaction products thereof with undetermined constitution), C12N15 (mutation or genetic engineering; DNA or RNA concerning genetic engineering, vectors, e.g., plasmids or their isolation, preparation or purification; use of hosts thereof), and A61K36 (medicinal preparations of undetermined constitution containing material from algae, lichens, fungi or plants or derivatives thereof), with numbers of 135,610, 128,333, and 89,079, respectively. More specifically, C12Q1/68, C12N15/11, A61P35/00, C12N1/20, and A61K35/78 are the five subgroups that have the most applications.

Figure 3.

Main IPC codes of the biotechnology patents (main group).

Figure 4.

Main IPC codes of the biotechnology patents (subgroup).

Table 2 provides the number of biotechnology patents in different provinces in China. Jiangsu is the province with the most biotechnology patents, and the number is 55,238, followed by Beijing, Shandong, Guangdong, and Shanghai. Some western provinces, such as Ningxia and Qinghai, have a very small number of applications.

Table 2.

Number of patents in different provinces.

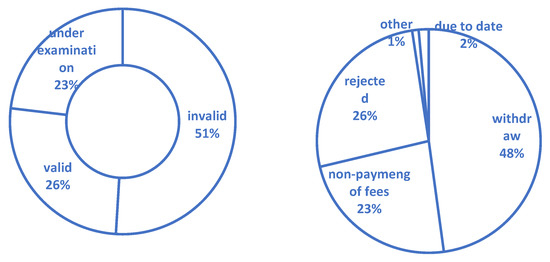

Figure 5 shows the legal status of the biotechnology patents in China. Presently, 51% of the 575,490 total applications are invalid, accounting for more than half. As seen from the right part of Figure 5, 48% of the invalid patents are withdrawn, 26% of the invalid patents are rejected and thus not granted from the start, and 23% of the patents are invalid due to the non-payment of fees. A total of 2% of the biotechnology patents that expired were due to patent term completion.

Figure 5.

Legal status of biotechnology technology.

To explain the increase in the number of biotechnology patents, we investigate the funding of research projects by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC). The NSFC is the department responsible for the management of science funding in China. Presently, there are nine science sectors in different fields under NSFC, and one of them was established in November 2020. By 2021, NSFC granted research projects in eight science sectors: Mathematics and physics science, chemistry science, life science, earth science, engineering and material science, information science, management science, and medical science. Table 3 and Table 4 show the funding situation in life science and medical science, which are closely related to biotechnology.

Table 3.

Funding on life science projects by the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Table 4.

Funding on medical science by the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

It is shown that the percentage of grants on life science projects has been sustained at a relatively high level, the value of which for general projects and youth projects is 19.21% and 17.45% in 2021, respectively. The total expense of medical science funding remains at a relatively high level; the amount for general and youth projects is 2497.68 and 1511.90 million Yuan in 2021, accounting for 22.53% and 24.07%, respectively. In 2021, the expense of general projects in the two fields accounted for 38.37% of the total expense of general projects, and the expense of youth projects in the two fields accounted for 37.62% of the total expense of youth projects. From this point, the government’s investment might be a key factor in encouraging biotechnology patents from academic organizations.

4.2. The Biotechnology Institution in China

The institution of biotechnology in China has also experienced evident dynamic development in recent decades. North [48] defined institutions as “the rules of the game in a society or, more formally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction”. In addition, institutions are divided into formal institutions (e.g., laws, regulations) and informal institutions (e.g., cultural tradition, manners, and customs). In this paper, we only focus on formal institutions. Institution is broadly understood in this work, including government arrangement, policies, and other institutional arrangements.

4.2.1. Government Departments

There are several departments involved in biotechnology administration in China under the present governance structure. These departments include the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), National Intellectual Property Administration (NIPA), National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), etc., as shown in Table 5. These departments constitute the administration system of biotechnology in China, covering the aspects of research and development (R&D), industry development, supervision, and commercialization.

Table 5.

Government departments involved in biotechnology administration.

4.2.2. Policies

The policies related to biotechnology are an important part of the biotechnology institution. The present policy system can be analyzed from two dimensions. The first dimension is the administrative level of the department issuing the document, which can be divided into three types: (1) The law and other document issued by the National People’s Congress (Table A1); (2) the regulations issued by the State Council (Table A2); and (3) the policy documents issued by the departments under the State Council (Table A3). The second dimension is the target area of the policies, and we divide the target into four types: (1) Technology development; (2) industry development; and (3) technology regulation (Table 6).

Table 6.

Main policies related to biotechnology.

The main aim of “technology development” is to promote the R&D of biotechnology. As early as 1988, the General Office of the State Council (GOSC) issued the Critical Policy Points of Biotechnology Development to promote biotechnology. In the Mid-Long Term S&T Development Plan (2006–2020), biotechnology was listed as the first of the eight cutting-edge technologies. In 2011, the MOST issued two documents related to biotechnology development: The 12th Five-Year Plan of Biotechnology Development and the National Mid-Long Term Biotechnology Talent Development Plan (2010–2020).

The main aim of “industry development” is to promote the development of biology industries and biotechnology-related industries. In 2009, GOSC issued the Notice on Issuing the Several Policies in Promoting the Biology Industry Development. In 2001, the biotechnology industry was listed as a high-tech industry in the 10th Five-Year Plan of High-tech Industry Development. In 2010, the biology industry was listed as one of the seven strategic new-emerging industries in China. In 2012, the State Council issued the Bio-Industry Development Plan. In 2016, the NDRC issued the 13th Five-Year Plan on Biology Industry Development.

The main aim of “technology regulation” is to set limitations and standards for R&D and the application of biotechnology to avoid harmful or illegal effects resulting from biotechnology. Genetically modified food (GMF), biomedical ethics, and human genetic resources are the three most important issues. In 2019, the State Council issued the Regulation on the Management of Human Genetic Resources, and its last version was in 1986. In 2017, the State Council issued the amended Regulation on Administration of Safety of Agricultural Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO), which was first issued in 2001 and revised in 2011; the former Ministry of Health issued the Measures for the Ethical Review of Biomedical Research Involving Humans; and MOST issued the Management Measures on Safety of Biotechnology Research and Development.

As can be seen from the administrative level of the policies, most of them are in the second and third levels. On the first level, the Biosecurity Law, which was published in 2020, aiming at “promoting the healthy development of biotechnology”, is the most relevant and the only law in the field of biotechnology. In the 14th Five-Year Plan, biotechnology-based industry is stressed, and a special section concerning biosecurity is included. On the second level, the State Council issues policies that are important in certain areas, and the State Council will transfer some important policies issued by the State Council departments in the name of the State Council to stress its importance by improving the policies’ level from the third to the second level. The departments under the State Council issued policies in accordance with their responsibilities, and these are third-level policies, e.g., the MOST is in charge of technology development, and the NDRC is in charge of industry development.

4.2.3. Other Institutional Arrangements

Apart from the government departments and the policies concerning biotechnology, there are still some other institutional arrangements related to biotechnology in China.

The first lies in the R&D of the biotechnology: National Key Laboratory (NKL). China started to establish NKL in the 1980s, and at present, NKLs have become a very important part of the innovation system in China, particularly in the field of basic research. By the end of 2016, there were 254 NKLs in total, and 40 of them belonged to the area of biotechnology, accounting for 15.7% of the total number [49].

The second lies in the industry cluster of biotechnology. The development zones and biotechnology industry bases play an important role. In 2018, the NDRC issued the Content of the Chinese Development Zone (2018 edition), and the content includes all the national and provincial development zones certified by governments. Among all 552 national development zones, 88 have a dominant industry related to biotechnology, contributing to 15.94%. In addition, since 2005, the NDRC has granted 22 biotechnology industry bases with four batches [50], and these industry bases also play an important role in the development of technology and industry.

The third lies in the protection of biotechnology. China started to establish its patent system in 1985. Even though it has been regarded as weak in patent protection [51], the government has made tremendous efforts to strengthen patent protection. The Patent Law, after its enactment, was revised four times in 1992, 2000, 2008, and 2020. In 2014, the Chinese government decided to establish three specialized intellectual property (IP) courts in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou to deal with increasing IP litigations.

5. Stakeholders in the Relationship between Biotechnology and Institution

In this section, we apply the stakeholder perspective to analyze the relationship between biotechnology and institutions.

5.1. Case Description

5.1.1. Discussion on the Safety of Genetically Modified Food (GMF)

Discussion on the safety of GMFs is a real-world issue [52], and has lasted for quite a long time in China [53]. On 27 October 2009, the MOA in China issued three safety certificates for transgenic crops, indicating that these crops were planned to be commercialized. However, safety issues have been broadly discussed, and Table 7 shows some key milestones in the process.

Table 7.

Timeline of the discussion on genetically modified food.

5.1.2. The “Gene-Edited Babies” Event

On 26 November 2018, a Chinese scientist, Jian-Kui He, declared that two of the world’s first genetically edited babies who are immune to HIV infection were born. This event raised broad worldwide attention and criticism concerning Jian-Kui He’s activity. Table 8 shows some key milestones in the event.

Table 8.

Timeline of the “gene-edited babies” event in China.

5.1.3. The Development of Vaccine Sand Detection Technology for COVID-19

At the end of 2019, the explosion of COVID-19 has spread throughout the world with strong impacts in various dimensions. The pandemic has brought significant losses to human life and the economy. To cope with the virus, the Chinese government adopted several measures to develop vaccines. The development, clinical trial, and approval of a vaccine typically last several years. However, China has shortened this process to several months with the development of different solutions through various approved COVID-19 vaccines. Institutions play important roles in the process, and some of the key milestones are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Timeline of COVID-19 vaccine development in China.

5.2. The Function of the Main Stakeholders

5.2.1. Government

Various government departments function simultaneously in administrating biotechnology from different angles, including the development of technology and industry, protection of invention, as well as supervision of food and medicine. The direct users of institutions include universities, industries, and consumers. The main functions of governments include: (1) Providing funding for the research of biotechnology in U & PRI, and regulating the research activity; (2) providing funding for the research and development of biotechnology in industry, regulating their research activity and production, and providing preferential policies (e.g., preferential taxation policy); and (3) creating policies to protect and benefit consumers, e.g., their right to know the information of GMF.

In the case of GMF safety, the main function of the government is to establish policies concerning genetically modified crops and GMF, set standards on the marketing and selling of GMF, and issue certificates to products of GMF. In the case of the “gene-edited babies” event, the government plays an important role, even though the government failed to avoid this event, yet several measures had been taken after the event, e.g., the punishment of the responsible scientist, the improvement of relative policies, especially the amendment of the Criminal Law and the issuance of the Biosecurity Law. In the case of COVID-19-related technologies, the government plays a significant role in promoting the fast development, approval, and production of the vaccines. Moreover, the government created policies to control the cost of detection of the novel coronavirus. This measure is based on the development of new efficient detection technologies and products, and is helpful for consumers.

5.2.2. Industry

The role of industry concerning biotechnology is reflected not only in producing products and selling them to consumers, but also in the R&D activity of biotechnology. Moreover, the industry has an important power on biotechnology research. The activities of industry are greatly affected by institutions. From the perspective of innovation value chain, first, the industry can apply for government funding projects to conduct R&D, and enjoy the reduction in taxes by conducting R&D. Second, institutions provide patent protection for the industry, guaranteeing their monopoly income. Third, by selling biotechnology products, the industry can again enjoy the reduction in taxes under certain conditions. At the same time, the development of industry influences the evolution of institutions. When the industries are weak in biotechnology and market power, they require the government to provide more public funding in R&D and provide protection to relatively weak patents for the industry to grow. With the development of the industry, they can in turn, be stronger in technology and apply for additional patents, which requires stricter patent protection from the government.

In the case of GMF safety, the development of the relative biotechnology industry required the legitimation of the GMF. Therefore, they are motivated to invest more in biotechnology R&D, and to push the government to formulate policies to identify their role. In the case of COVID-19-related technologies, the industry made important contributions to developing vaccines, such as the Wuhan Institute of Biological Products Co., Ltd., Sinovac Biotech Ltd., and CanSino Biologics Inc.

5.2.3. University and Public Research Institute (U & PRI)

U & PRIs are the most important contributors to biotechnology development in China. They sell or license out the technology to industries, and then the technologies are commercialized to industries, that in turn, are introduced to the market. Fiscal expenditure is an important source of research funding. Meanwhile, universities may also receive funding from industry or establish laboratories in alliance with industry. At the same time, the R&D activities in U & PRI are regulated by the institution, and the U & PRI also establish internal rules to regulate the behavior of their employed scientists.

In the case of GMF safety, transgenic rice that received the first two safety certifications was developed by the research team at Huazhong Agricultural University. In the case of “gene-edited babies”, scientist Jian-Kui He is a professor of the Southern University of Science and Technology. Even though the university tried to stay out of trouble, there is no doubt that the university is responsible for administering its staff. In the case of COVID-19-related technologies, various research groups from the U & PRIs are involved in research on vaccines to promote the innovation process.

5.2.4. Scientist

Scientists are the direct entities that conduct the R&D of biotechnology. Similar to the role of U& PRI, scientists receive funding from the institution to conduct research, and the institution encourages their innovation work. At the same time, their research work is regulated by the institution, and should comply with the policies.

In the case of GMF safety, scientists play a significant role in promoting the commercialization of GMFs. For example, a scientist named Qi-Fa Zhang, who is an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, delivered speeches and comments concerning the safety and advantages of GMF several times. In fact, he is also the principal scientist in the research project of transgenic rice, which received the first two safety certifications in China. Another example lies in the activity of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Biotechnology in issuing the “Truth of the ten Rumors about Transgenesis”, which is helpful for consumers to better understand and accept GMF. In the case of “gene-edited babies”, many scientists criticized Jian-Kui He’s scientific misconduct and violation of research ethics. In the case of COVID-19-related technologies, individual scientists are also important in leading the research, such as Chen Wei from the Military Medical Research Institute, and Yang Xiao-Ming from CNBG.

5.2.5. Consumer

The food that people eat and the medicine that people use are all related to biotechnology. In the process of dealing with those items, consumers will provide feedback to the industry and government, thus influencing their decisions. In the case of GMF safety, consumers think they have the right to clearly know whether the products they buy are genetically modified crops. When consumers find that their rights are not respected, they safeguard themselves by filing lawsuits, which attracts the attention of the government to improve institutions. In the case of COVID-19-related technologies, consumers have a high and frequent need for nucleic acid detection of the novel coronavirus, and this requirement forms a huge market and encourages the development of new technologies. At the same time, the opinion of the consumers also influences the government’s decision in controlling the price.

6. Main Findings

6.1. Biotechnology Interacts with Institution Dynamically

The basic framework of biotechnology institutions has been established in China. There are different departments in charge of different administrative areas of biotechnology. Various laws, plans, regulations, and other policies concerning biotechnology have been issued. Different institutional measures are taken to promote the development of the biotechnology and biotechnology industry, e.g., the NKL and the development zone.

Institution co-evolves together with the development and application of biotechnology. However, the growth of biotechnology research is very rapid, while the improvement of institutions is relatively slow. Therefore, institutions require time to step up the pace. Thirty years ago, China has noticed the importance of biotechnology and biotechnology industry, since the GOSC put forward a policy to promote biotechnology in 1988. Even though the government issued a policy concerning the safety of agricultural GMOs as early as 2001, this did not prevent the intense discussion concerning the safety of GMFs in society when the GMFs were placed in the market, and consumers’ worries were not relaxed by the policy. The GMF institutional system gradually improved in recent years, and the 2001 GMO-safety-related document was amended until 2017.

The improvement of institutions is pushed by the development and application of biotechnology. In the case of “gene-edited babies”, although the responsible scientist was punished, the name of the crime was “illegal medical practice”. However, to some degree, it is not fully suitable to judge who is guilty in this event. The crime of “illegal medical practice” should be based on the fact of “medical practice”, while the activity of Jian-Kui He was more of “medical research” rather than “medical practice”, and the role of Jian-Kui He was a researcher rather than a doctor. The event of “gene-edited babies” directly led to the amendment of the Criminal Law in China in 2020, and a new article was added, defining a new crime named “crime of illegally implanting gene editing and cloning embryos”, which is targeted at a similar activity with the “gene-edited babies”.

6.2. The Interaction between Biotechnology and Institutions Is Affected by Stakeholders

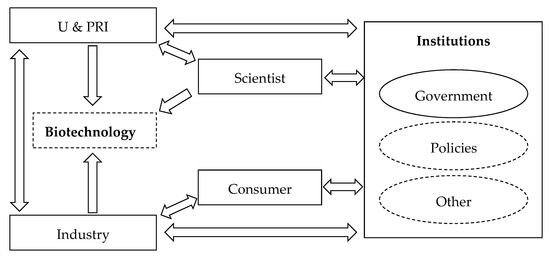

A variety of stakeholders function in the interaction between biotechnology and institutions, and the interaction mechanism is affected by a system consisting of all stakeholders (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Interaction mechanism of biotechnology and institutions. The main stakeholders are depicted in the solid line box; and in the dotted line box, main elements that cannot be defined as stakeholders are shown.

Biotechnology is developed through various mechanisms: (1) U & PRIs and their scientists conduct research on biotechnology to obtain academic reputation; (2) industries also invest in R&D on biotechnology to achieve market return, and they sometimes cooperate with U & PRIs; and (3) the government encourages the development of biotechnology in U & PRI and industry to drive the progress of the economy and society. However, the R&D of biotechnology may be misconducted, and biotechnologies may be improperly used. Therefore, policies to regulate the technologies are required. In the absence of specific regulation, the occurrence of an emergency incident can speed up the process of institutional progress. However, society will undertake the cost brought by the emergency.

7. Concluding Remarks

7.1. Conclusions

This article presents an update on biotechnology-related institutions in China. We study the interaction mechanism of biotechnology and biotechnology-related institutions under the context of China. As can be seen from the number of patent applications, the development of biotechnology has improved considerably. Universities that are supported by public funds are an important contributor, in line with prior findings [3,14]. The institution concerning biotechnology consists of governments, policies, and other institutional arrangements. It is found that biotechnology co-evolves with the institution, and the interaction is affected by various stakeholders.

The roles of institutions in biotechnology are mainly reflected in two aspects: Promotion and regulation. First, the R&D and experiment of biotechnology usually takes a long time and faces great risk, and this requires the government to take action. This may be part of the reason why universities patent a lot of biotechnology, considering that they can receive more research funding from government than companies. Second, the R&D and application of biotechnology may have a negative impact on food safety, medicine safety, and biodiversity. Biotechnology is usually concerned with ethical issues, and new biotechnologies of cloning technology, artificial insemination, and test-tube baby challenge traditional perceptions. Moreover, these technologies have a potential influence on the evolution and development of human beings, of which we still do not know whether the influence is good or not. Biotechnologies used in optimizing crops may be harmful to ecological balance and biodiversity, and eating GMF still has uncertainty for people’s health. Biotechnology has the possibility of use as virus in war. All of these require governments to set standards to regulate the behavior of stakeholders.

7.2. Discussions

The development of biotechnology is important in the context of the bioeconomy [5,54,55], and the establishment of an efficient regulatory system is required [3] as a major influencing factor of the bioeconomy [7]. Technological innovations are a powerful driver in promoting economic development, but may result in severe social or environmental issues if not well regulated [56,57]. To reach a sustainable development goal, the benefits and potential adverse impacts require balance, with the role of different stakeholders considered. Motivated by these drivers and opportunities, this article analyzed the institutions of biotechnology.

This research mainly contributes to research on technology governance [56,58,59,60,61], particularly biotechnology governance [57,62,63,64]. “With the increasingly prominent position and the important role of biotechnology in national development systems”, it is necessary to achieve good governance by establishing fair laws and regulations [62]. However, “creating new institutions is always a challenging task and should not be undertaken lightly” [59]. Prior studies on this topic have increasingly focused on the context of developed countries [65,66,67,68,69,70]. However, this issue is also important in developing countries, where biotechnology has developed quickly and, if not properly regulated by institutions, may cause severe problems, such as the event of “gene-edited babies” in China. In recent years, China has taken various measures to catch up with developed countries in the field of science and technology. However, institutions cannot keep up with new technologies, particularly in developing countries where increased attention has been provided to the economic-growth effect of technology rather than the potential harm. With the use of China as a context, we explain how biotechnology interacts with institutions.

7.3. Implications

Based on the above analysis, we achieved the following implications, mainly for policy makers. First, even though a large number of biotechnology patents are submitted in China, this may not indicate that the real technological innovation level has improved equally. Universities are an important contributor to biotechnology patents, yet most of those patents are generated by undertaking government-funded research projects. In addition, professors are motivated to apply for patents since they can receive faster promotion. As a result, many patent applications are of low quality and are difficult to use in the industry. Therefore, investment in the R&D of biotechnology still requires increased attention and leans toward the private sector. The role of universities and industries in the innovation system of biotechnology should be clarified. Industry should be at the core of the system, and firm innovators are strongly required. Even though the government in China has taken measures to cultivate the biotechnology industry, the effect is required for evaluation and strengthening.

Second, although the framework of biotechnology institutions has been established, it still requires improvement. Some important issues, such as biosafety, biodiversity, GMF, ethics, and genetic resources, have been noticed, yet a systemic institutional environment has not been formed, and detailed rules for implementation are required, e.g., the establishment of a national ethical review system. Therefore, there is an urgent need for the regulation of the ethics of biotechnology in China. The lack of regulations may result in two possible risks: Chinese researchers conduct biotechnology research at their will, and foreign researchers may conduct forbidden biotechnology research in China, which is prohibited in their country. Therefore, China is required to set up laws that protect gene information to clarify the ethical rules in R&D and the use of biotechnology.

Third, China is required to establish specific policies to implement the Biosecurity Law. In recent years, biotechnology safety has raised wide attention in China. In addition, the Biosecurity Law was finally put forward in 2020, setting basic rules, standards, and processes in dealing with biotechnology, yet specific measures have to be taken to implement the law.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-F.Z.; methodology, Y.-F.Z.; formal analysis, Y.-F.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-F.Z.; writing—review and editing, T.Q.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Main Government Documents of Biotechnology

Table A1.

Law and other Policy Documents of National People’s Congress.

Table A1.

Law and other Policy Documents of National People’s Congress.

| Policy Document | Department |

|---|---|

| Biosecurity Law | National People’s Congress, 2020 |

| Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and the Vision for 2035 | National People’s Congress, 2021 |

Table A2.

Policy Documents of the State Council.

Table A2.

Policy Documents of the State Council.

| Policy Document | Department |

|---|---|

| Opinions on Strengthening the Governance of S&T Ethics | General Office of the CPC Central Committee (GOCC), GOSC, 2022 |

| Regulation on the Management of Human Genetic Resources. Order No. 717 of the State Council | State Council, 1986 (revised in 2019) |

| Opinions on Strengthening the Protection of Aquatic Organisms in the Yangtze River | GOSC, 2018 |

| Regulation on the Biosafety Management of Pathogenic Microbe Labs. Order No. 424 of the State Council | State Council, 2004 (revised in 2016 and 2018) |

| Regulation on Administration of Safety of Agricultural Genetically Modified Organisms. Order No. 687 of the State Council | State Council, 2001 (revised in 2011 and 2017) |

| Bio-Industry Development Plan. Guo Fa [2012] No. 65 | State Council, 2012 |

| Notice on Issuing the Several Policies in Promoting the Biology Industry Development. Guo Ban Fa [2009] No. 45 | GOSC, 2009 |

| 11th Five-Year Plan of Biology Industry Development. Guo Ban Fa [2007] No. 23 | GOSC, 2007 |

| Opinions on Precaution of Alien Invasive Species | GOSC, 2003 |

| List on Export of Dual-Use Biological Agents and Relative Equipment and Technology | State Council, 2002 (revised in 2006) |

| Outline of Action in protection of the Aquatic Organisms Resources | State Council, 2006 |

| Mid-Long Term S&T Development Plan (2006–2020). Guo Fa [2005] No. 44 | State Council, 2005 |

| Notice on Strengthening the Protection and Administration of Biological Species Resource | GOSC, 2004 |

| Critical Policy Points of Biotechnology Development. Guo Ban Fa [1988] No. 18 | GOSC, 1988 |

Table A3.

Policy Documents of the State Council departments.

Table A3.

Policy Documents of the State Council departments.

| Policy Document | Department |

|---|---|

| Management Measures on Safety of Biotechnology Research and Development. Guo Ke Fa She [2017] No. 198 | MOST, 2017 |

| 13th Five-Year Plan of Biotechnological Innovation. Guo Ke Fa She [2017] No. 103 | MOST, 2017 |

| 13th Five-Year Plan on Biology Industry Development. Fa Gai Gao Ji [2016] No. 2665 | NDRC, 2016 |

| Building Plan of High-Level Biosafety Laboratory System (2016–2025) | NDRC and MOST, 2016 |

| 13th Five-Year Plan of Biomass Energy Development | NEA, 2016 |

| Measures for the Ethical Review of Biomedical Research Involving Humans. Order No. 11 of NHC | National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC, presently NHC), 2007 (revised in 2016) |

| Development Policies for the Biodiesel Industry | NEA, 2014 |

| Development Plan on National Forest Biomass Energy (2011–2020) | State Forestry Administration (SFA, present NFGB), 2013 |

| 12th Five-Year Plan of Biomass Energy | NEA, 2012 |

| National Mid-Long Term Biotechnology Talent Development Plan (2010–2020). Guo Ke Fa She [2011] No. 673, 2011 | MOST, 2011 |

| 12th Five-Year Plan of Biotechnology Development. Guo Ke Fa She [2011] No. 588 | MOST, 2011 |

| Urgent Notice on strengthening the Administration of Research on Highly Pathogenic Microorganisms | Ministry of Agriculture (MOA, presently MARA), 2005 |

| Method on Administration of Genetic Engineering Safety | State Scientific and Technological Commission (SSTC, presently MOST), 1993 |

References

- Commission of the European Communities. Preparing for Our Future: Developing a Common Strategy for Key Enabling Technologies in the EU. 2009. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex%3A52009DC0512 (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- OECD. A Framework for Biotechnology Statistics; OECD: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zilberman, D.; Kim, E.; Kirschner, S.; Kaplan, S.; Reeves, J. Technology and the Future Bioeconomy. Agric. Econ. 2013, 44, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Chichakli, B.; von Braun, J.; Lang, C.; Barben, D.; Philp, J. Policy: Five Cornerstones of a Global Bioeconomy. Nature 2016, 535, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugge, M.M.; Hansen, T.; Klitkou, A. What Is the Bioeconomy? A Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2016, 8, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rabitz, F. Institutional Drift in International Biotechnology Regulation. Glob. Policy 2019, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, K.; Kautto, N. The Bioeconomy in Europe: An Overview. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2589–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arujanan, M.; Singaram, M. The Biotechnology and Bioeconomy Landscape in Malaysia. New Biotechnol. 2018, 40, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktorowicz, M.; Deber, R. Regulating Biotechnology: A Rational-Political Model of Policy Development. Health Policy 1997, 40, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyranoski, D.; Ledford, H. Genome-Edited Baby Claim Provokes International Outcry. Nature 2018, 563, 607–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Did CRISPR Help—or Harm—the First-Ever Gene-Edited Babies? Science 2019, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Wang, F. Gene-Edited Baby by Chinese Scientist: The Opener of the Pandora’s Box. Sci. Insigt 2018, 2018, e000178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyranoski, D. What CRISPR-Baby Prison Sentences Mean for Research. Nature 2020, 577, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Guan, J. Mapping of Biotechnology Patents of China from 1995–2008. Scientometrics 2011, 88, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dongen, P.; Tak, H.; Claassen, E. Policies and Patenting to Stimulate the Biotechnology Sector: Evidence from The Netherlands. Sci. Public Policy 2019, 46, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronzini, R.; Piselli, P. The Impact of R&D Subsidies on Firm Innovation. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geuna, A.; Rossi, F. Changes to University IPR Regulations in Europe and the Impact on Academic Patenting. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henderson, R.; Jaffe, A.B.; Trajtenberg, M. Universities as a Source of Commercial Technology: A Detailed Analysis of University Patenting, 1965–1988. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1998, 80, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundel, A. Biotechnology Indicators and Public Policy; OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers; OECD Publications: Paris, France, 2003; Volume 2003/05. [Google Scholar]

- Aghmiuni, S.K.; Siyal, S.; Wang, Q.; Duan, Y. Assessment of Factors Affecting Innovation Policy in Biotechnology. J. Innov. Knowl. 2020, 5, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Cao, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Y. Bioindustry in China: An Overview and Perspective. New Biotechnol. 2018, 40, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, P.A.; Knight, A.J. Trends Affecting the next Generation of U.S. Agricultural Biotechnology: Politics, Policy, and Plant-Made Pharmaceuticals. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2005, 72, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Cooke, P.; Wu, F. State-Sponsored Research and Development: A Case Study of China’s Biotechnology. Reg. Stud. 2011, 45, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murmann, J.P. Knowledge and Competitive Advantage: The Coevolution of Firms, Technology, and National Institutions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.R. The Co-Evolution of Technology, Industrial Structure, and Supporting Institutions. Ind. Corp. Chang. 1994, 3, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Börner, J.; Förster, J.; von Braun, J. Governance of the Bioeconomy: A Global Comparative Study of National Bioeconomy Strategies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, M.W.; Sun, S.L.; Pinkham, B.; Chen, H. The Institution-Based View as a Third Leg for a Strategy Tripod. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2009, 23, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliver, C. Sustainable Competitive Advantage: Combining Institutional and Resource-Based Views. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, M.W. Towards an Institution-Based View of Business Strategy. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2002, 19, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Ahlstrom, D.; Carraher, S.M.; Shi, W. An Institution-Based View of Global IPR History. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2017, 48, 893–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz, R.A.; Rosenthal, S.B. Stakeholder Theory and Public Policy: How Governments Matter. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 51, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Romero, J.; Bilro, R.G. Stakeholder Engagement in Co-Creation Processes for Innovation: A Systematic Literature Review and Case Study. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 388–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilly, D.; Zollo, M.; Hansen, M.T. Faking It or Muddling Through? Understanding Decoupling in Response to Stakeholder Pressures. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1429–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, B.L.; Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Purnell, L.; de Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art. Annals 2010, 4, 403–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplume, A.O.; Sonpar, K.; Litz, R.A. Stakeholder Theory: Reviewing a Theory That Moves Us. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 1152–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunan, X.; Weixin, L.; Yujie, Y.; Hui, W. Evolutionary Game for the Stakeholders in Livestock Pollution Control Based on Circular Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 125403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prud’homme, D.; Tong, T.W.; Han, N. A Stakeholder-Based View of the Evolution of Intellectual Property Institutions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 52, 773–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, L.B.; Nabatchi, T.; O’Leary, R. The New Governance: Practices and Processes for Stakeholder and Citizen Participation in the Work of Government. Public Adm. Rev. 2005, 65, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Business & Society: Ethics and Stakeholder Management, 3rd ed.; Cengage Learning, Inc.: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Siggelkow, N. Persuasion With Case Studies. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, G.; Katila, R. Technological Acquisitions and the Innovation Performance of Acquiring Firms: A Longitudinal Study. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carree, M.; Piergiovanni, R.; Santarelli, E.; Verheul, I. Factors Favoring Innovation from a Regional Perspective: A Comparison of Patents and Trademarks. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beuzekom, B.; Arundel, A. OECD Biotechnology Statistics-2009; OECD: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrichs, S.; van Beuzekom, B. Revised Proposal for the Revision of the Statistical Definitions of Biotechnology and Nanotechnology; OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- North, D. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Di, Y.; Chen, R. A Brief Introduction of the National Laboratory and National Key Laboratory. Mod. Sci. 2019, 7, 24–33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Sun, L. Development Status and Problems of Biomedical Industrial Parks in China. Chin. J. New Drugs 2019, 28, 2440–2446. [Google Scholar]

- Keupp, M.M.; Friesike, S.; von Zedtwitz, M. How Do Foreign Firms Patent in Emerging Economies with Weak Appropriability Regimes? Archetypes and Motives. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1422–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teferra, T.F. Should We Still Worry about the Safety of GMO Foods? Why and Why Not? A Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 5324–5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, J.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, X. Agricultural GMO Safety Administration in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14, 2157–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sili, M.; Dürr, J. Bioeconomic Entrepreneurship and Key Factors of Development: Lessons from Argentina. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokko, Y.; Heijde, M.; Schebesta, K.; Scholtès, P.; Van Montagu, M.; Giacca, M. Biotechnology and the Bioeconomy—Towards Inclusive and Sustainable Industrial Development. New Biotechnol. 2018, 40, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linstone, H.A. Technology and Governance: An Introduction. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 1997, 54, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raybould, A. New Frontiers in Biosafety and Biosecurity. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oudheusden, M. Where Are the Politics in Responsible Innovation? European Governance, Technology Assessments, and Beyond. J. Responsible Innov. 2014, 1, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marchant, G.E.; Wallach, W. Coordinating Technology Governance. Issues Sci. Technol. 2015, 31, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fosch-Villaronga, E.; Heldeweg, M. “Regulation, I Presume?” Said the Robot—Towards an Iterative Regulatory Process for Robot Governance. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2018, 34, 1258–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, R.; Christin, N.; Edelman, B.; Moore, T. Bitcoin: Economics, Technology, and Governance. J. Econ. Perspect. 2015, 29, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qianqian, G.; Jinjin, W. Legal Prevention of Biotechnology Risks from the Perspective of COVID-19 Pandemic. Sci. Technol. Law 2021, 1, 140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Yu, H.; Qin, G. Towards Good Governance on Dual-Use Biotechnology for Global Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graeff, N.; Dijkman, L.E.; Jongsma, K.R.; Bredenoord, A.L. Fair Governance of Biotechnology: Patents, Private Governance, and Procedural Justice. Am. J. Bioeth. 2018, 18, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, S.J.; Wesseler, J. The Future of Genome Editing Innovations in the EU. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, D.; Custers, R.; Edvardsson Björnberg, K.; Hansson, S.O.; Purnhagen, K.; Qaim, M.; Romeis, J.; Schiemann, J.; Schleissing, S.; Tosun, J.; et al. Options to Reform the European Union Legislation on GMOs: Scope and Definitions. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, H.; Taduri, S.; Kesan, J.; Lau, G.; Law, K.H. Mining Information across Multiple Domains: A Case Study of Application to Patent Laws and Regulations in Biotechnology. Gov. Inf. Q. 2012, 29, S11–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzma, J. A Missed Opportunity for U.S. Biotechnology Regulation. Science 2016, 353, 1211–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, I.M. Regulation of Biotechnology: Will We Ever ‘Freely’ Trade GMOs? Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2002, 29, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karky, R.B. Japanese Biotechnology Regulation and Life Science (Gene) Patenting. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2021, 24, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).