1. Introduction

More than half of the world’s population lives in urban areas, a proportion that is expected to increase to 66% by 2050, and the number of cities in developing countries will have tripled by 2030 [

1,

2]. Large-scale urbanization has been happening autonomously and has been actively advocated for by individuals, collective powers, and states since the 19th century [

3,

4]. Cities are now the main centers for technology development, innovation, education, commerce, administration, transportation, medical care, human resources and more, and around 80% of global gross domestic product (GDP) is generated in cities [

4,

5]. Further development of cities is discussed within the idea of smart cities, however, the smartness as such also refers to the rural areas.

According to the definition presented by European Network for Rural Development (ENRD) [

1], “Smart villages are communities in rural areas that apply innovative solutions to improve their resilience, taking advantage of local strengths and opportunities. They rely on a participatory approach to develop and implement their strategy to improve their economic, social, and/or environmental conditions, in particular mobilizing solutions offered by digital technologies. Smart villages benefit from cooperation and alliances with other communities and actors in rural and urban areas. The initiation and implementation of smart village strategies is based on existing initiatives and can be funded by a variety of public and private sources” [

1].

An important role in the implementation of the concept of smart villages refers to solutions to improve the quality of life, depopulation, underinvestment, ageing society, depopulation, increasing the quality of services and safety, respect for the local environment, insufficient job opportunities, and digital divide. What can be underlined in particular is the importance of not associating this concept with issues such as digitization of villages, providing ready-made solutions to existing social problems related to the above challenges, and repetition of existing solutions [

2].

The aim of the smart village concept is to focus on energy, vision, and commitment of local people towards local action. The examples of projects and initiatives identified so far clearly show that smart villages start with local people organizing themselves around a common problem or shared vision to implement some form of ‘action plan’ to achieve a specific goal. Ideas of smart villages refer in concept to the ideas of smart cities. The question under discussion is how these two dimensions are interconnected.

The main objective of the work is to evaluate the role of partners from urban centers in local development concepts of rural areas in order to find the potential for future cooperation. The following research questions have been formulated in order to fulfill the main objective.

- Q1.

Are partners from urban centers identified in rural economic development concepts?

- Q2.

How significant a role do partners representing cities play in conceptualizing innovative development activities in rural areas?

- Q3.

How strong is the supra-local stakeholders’ influence on the implementation of concepts of innovative pro-social and pro-economic activities in rural areas?

The manuscript is organized as follows: in the first part, the literature review underlining the concept of partnerships and modern village organization is presented. In the next section the methodology underlining the case study method has been placed. Then, there is the research results section followed by the discussion section. At the end of the work, the conclusion and practical implications are provided. The manuscript ends with the references.

3. Materials and Methods

The choice of case study method, as Robert Yin points out [

33], occurs when “(1) your main research questions are: how or why questions (2) you have little or no control over behavioral events and (3) your focus of study is a contemporary (as opposed to entirely historical) phenomenon—a case”. As the researcher further points out, the reference can apply to a single case as well as a multiple case. Moreover, a case study can be an exclusive research method as well as one of the research methods for making observations and indicating regularities in the occurring and observed processes [

33]. A particular recommendation to use the case study method is the existence of a need for in-depth description of social phenomenon [

33].

The presentation and explanation of a social phenomenon, which includes facts and events and has an idiographic approach” [

34] entitles us, among others, to apply the case study method, which, unlike the theoretical approach, is based mainly on empirical data [

35].

The research questions identified in the introductory part of this paper are directly related to rural development and the participation of urban partners in this development. The first question is a general one, leading to the next two, which concern the specificity of rural areas. The two specific questions can be considered to follow the logic of the case study method due to their specificity. (1) How significant a role do partners representing cities play in conceptualizing innovative development activities in rural areas? (2) How strong is the supra-local stakeholders’ influence in the implementation of concepts of innovative pro-social and pro-economic activities in rural areas?

The case study method is commonly used to describe and analyze economic phenomena [

36], and allows us to build, based on the analysis of these phenomena, theories [

37,

38]. The application of the case study method in relation to the questions posed, as well as in relation to the formulated paper objective, results from an attempt to gain knowledge in terms of a generalized perspective on rural development, following the theory of smart cities, and at the same time an attempt to identify the gap of cooperation with urban stakeholders, which at the same time provides an opportunity to estimate the potential of this cooperation for the future. Various differentiated approaches are used to create studies of descriptions of phenomena, assuming scenarios for their construction and also the importance of describing the environment and context. In their logic, case studies are utilized as the constructive purpose of pointing out generalized conclusions, which lead to the development of considerations regarding the possibility of considering them as regularities for the description of similar phenomena in the future [

39]. The use of the case study method allows us to increase the level of detailed description of the object or phenomenon under study, however, the limitations that accompany the use of this method should also be pointed out—low representativeness, intuitive and subjective interpretation, as well as time and funds intensification.

The diversity that applies to European regions, which is embodied in the concept of smart regional specializations, also applies to rural areas, which are territorially predominant. The research questions refer to the phase of conceptualization and implementation of innovative solutions in rural areas and concern the level of involvement of supra-local stakeholders in these processes.

The choice of rural regions in Poland, to be analyzed for the involvement of supra-local partners in the conceptualization and implementation phases of innovative solutions in rural areas, results from the interesting and unique developmental solutions observed in these areas due to the research conducted over the last two years. On the other hand, the choice of the method of comparative analysis of the initiatives was selected as the purposeful method, given the diversity of the subject of the development initiatives:

The coordinator is a small number of enthusiasts;

The conception of the initiative is of a social innovation nature;

The reference to urban stakeholders in the implementation of the initiative is noticeable.

Adapting the multiple cases study method to the description of phenomena in rural areas results from the specificity of these areas, as well as the specificity and uniqueness of the initiatives undertaken there. Despite the fact that the problems and challenges in rural studies [

40,

41] seem to have a similar dimension, regardless of geographical location or economic situation, the directions of development activities in these areas may already be subject to their own specificity due to such conditions as, e.g., historical and cultural ones.

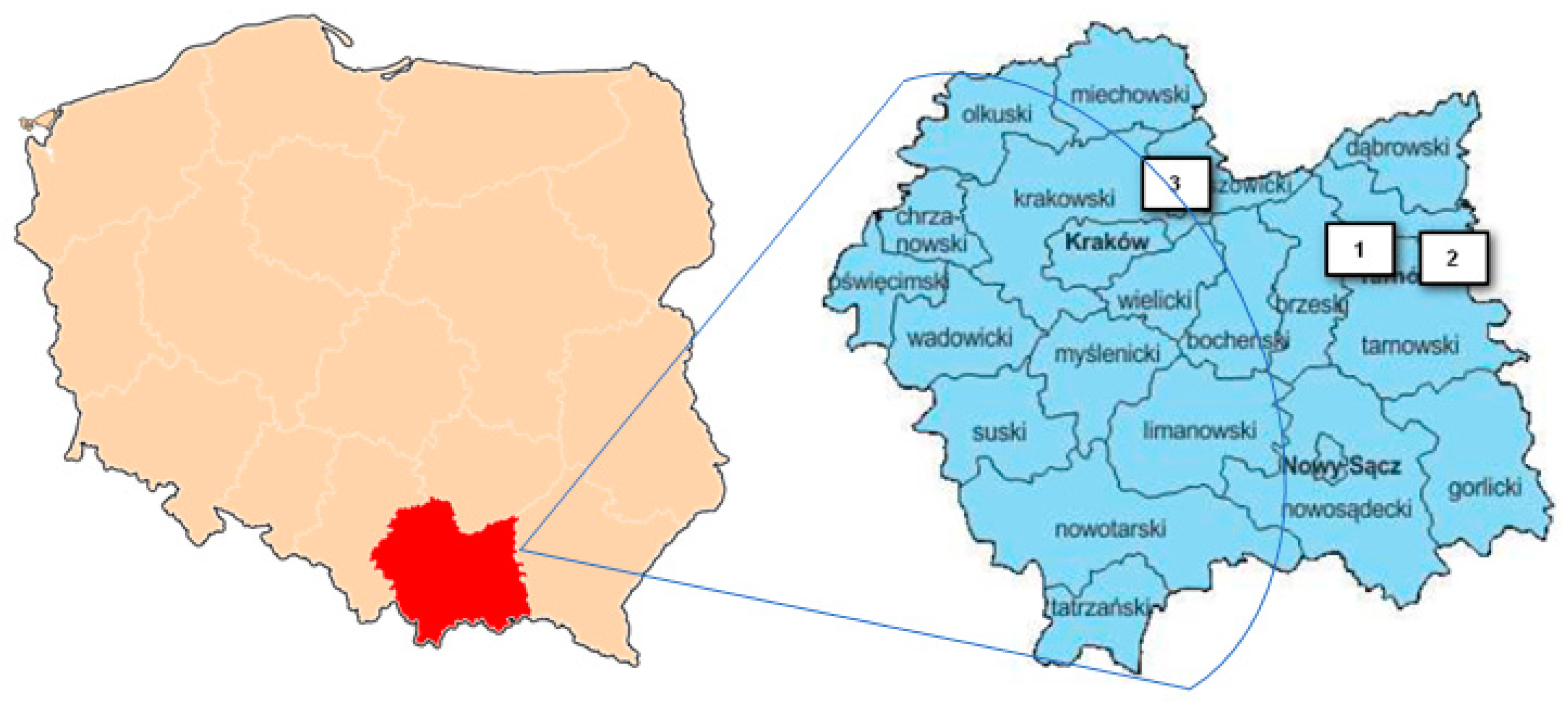

The areas of interest presented in the “Research results” section are within the EU region NUTS 2, based in Malopolska, southern Poland (

Figure 1).

The described examples of initiatives concern the area of Lesser Poland Voivodship, in the regions where the density of business entities is the lowest (

Figure 2), i.e., the areas where the development initiatives are supposed to be the most desirable. The development of rural areas, in expert opinion, depends significantly on the development of economic activity [

41].

Apart from the greatest significance of activities in the field of micro and small entrepreneurship for the development of rural areas, social entrepreneurship is equally important, which manifests itself, among others, in the functioning of social economy entities, such as foundations and associations.

Figure 3 presents graphically the number of non-governmental organizations in the described area and their density in the region.

The development initiatives presented in the next section, where possible directions of rural inhabitants’ activation are described, pertain to three rural areas within the powiats territorial range with diversified characteristics in terms of the number of business entities and non-governmental organizations. Apart from territorial diversification with regard to the location of initiatives, the examples described also refer to the diversified nature of activities, i.e., economic and social initiatives. In addition to territorial variety and the nature of the activity, the initiatives differ in approach to socio-economic activation of the population and a range of impacts.

The initiatives of social and economic character were developed by local leaders, residents of the areas analyzed, who, due to their involvement, qualify as local experts and activists. The observations and conclusions included in the respective descriptions of initiatives with respect to the identified local problems, objectives, and activities aimed at elimination and minimization of the observed deficiencies and shortcomings are the result of long-term activities, e.g., own observations, interviews, and discussions with inhabitants, information obtained from the local media, as well as reports and participation in local council meetings. Moreover, among the members of local groups responsible for the initiatives there are members of the local public administration, which additionally gives credibility and increases the value of the research material.

4. Research Results

The case studies presented are descriptions of development initiatives in three municipalities of Southern Poland, which represent (as indicated in the methodological section) provincial areas with the lowest level of economic and social entrepreneurship. Descriptions of individual initiatives include a section on the conditions, e.g., the number of inhabitants and the communal territorial area, an indication of the main problems that constitute the basis of the region’s developmental barriers, and a brief proposal to overcome these problems through economic or social activity (or jointly an initiative with a socio-economic background, such as a foundation with a business formula). Brief descriptions include, among others, identification of stakeholders defined as internal and external, main goals of the initiative, outline of actions planned to be undertaken, and resources. There is no direct structuring of the above elements in the case studies presented below, the information is presented collectively in a descriptive form.

4.1. The Case of Pleśna: Winoteka Initiative

The initiative refers to the commune of Pleśna (No. 1 on

Figure 1), where the vineyards Janowice, Dąbrówka, Uroczysko, Zadora, Epigon, and others are located. The Pleśna commune is located in the Małopolska province, in Tarnów county. It covers an area of 83.56 km

2. The number of inhabitants is 11,946 (as of 31.12.2017).

The identified problem was the lack of opportunities for small family farms and local wine producers to sell their products due to the lack of adequate promotion of the area and a place adapted to sell local products. Therefore, the main objective of the initiative was creating an outlet for local products for small family farms and local producers. Additional formulated goals included: promotion of the region and raising awareness about local products and strengthening cooperation between farms in the municipality.

The first stage of this initiative is to set up a foundation with a for-profit option in order to create a store with local products sourced directly from small family farms and local producers. The nature of the store is not purely profit-making, but also promotional—to increase awareness of potential customers (in and outside the region) about local products, which will directly translate into promotion of the region. Among the potential internal stakeholders, the following were identified: foundation managing the store and people connected with the foundation as well as the Pleśna municipality. As for the external stakeholders, the following were identified: community of local producers and suppliers, potential customers (both local people and tourists visiting the region) and competitive wineries and stores.

The initiative addresses two target groups. The first one consists of small households and small producers. The project should allow them to improve their economic situation (due to the possibility of selling the products) and should also contribute to increase cooperation between farms—creation of community of producers around the foundation, underlining the benefits of cooperation. The second target group refers to the potential customers, including tourists visiting the region. The main objective of the activities within this group is to promote the region. The main objective of the activities within this group is to promote the region and local products by offering the highest quality products, which are not available in “ordinary” stores. The foundation and its store should facilitate the way for households and local entrepreneurs to sell their products, thus giving them an additional source of income.

Currently, there is no store selling local wines in the community (one place with products from different vineyards). This kind of store seems, therefore, to be an ideal solution for tourists, who want to buy different kinds of products without the need to drive around the vineyards. The solution can be adopted in the surrounding communes or scaled up to a joint project connecting several counties, as the entire area (which includes Tarnów, Brzesko, and Dąbrowski counties) abounds in local vineyards. Among key human resources, the following were identified: board of founders, people who raise funds from outside sources, and staff responsible for operating the store. The key physical resources include premises (point of sale) based on long-term lease from the municipality, equipment of the premises and additional furniture as well as office supplies.

The activities to be taken in order to fulfill the goals have been divided into three stages:

Phase 1: Establishing the foundation, where preliminary market analysis needs to be performed, creating a business plan, presentation of the business plan to the municipality in order to obtain premises and finally establishing the foundation;

Phase 2: Preparing the activity with finalizing the lease agreement with the municipality, purchasing necessary equipment, negotiating contracts with local suppliers, preparing the premises to commence sales and finally launching of promotional activities (SM, publications in the local press and on associated websites);

Phase 3: Commencement of sale where the first activity would be opening of the store and beginning of stationary and online sales and cyclical information and promotional publications.

4.2. The Case of Skrzyszow: Beekeeping Incubator

The initiative covers the municipality of Skrzyszów (No. 2 on the

Figure 1), which was awarded as a bee-friendly municipality in 2017. There are numerous apiaries in the municipality run by beekeepers affiliated with the Skrzyszów Beekeepers Club. The Skrzyszów commune is located in the Małopolska province, in Tarnów county. It covers an area of 86.23 km². The population is 14,303 (as of 31.12.2019).

The problem of the area has been identified as the lack of possibility to legally obtain honey and market it outside of direct sales or agricultural retail trade. This is due to the lack of financial resources of individual beekeepers to be able to adapt their studios to the requirements of direct sales, i.e., the room and beekeeping equipment—honey extractors, separators, etc. The club has its own entity where statutory activities are discussed and materialized, however, it is a small room that does not meet the veterinary requirements allowing for the sale of so-called “traditional product”, i.e., goldenrod honey from the Skrzyszów commune.

The main objective of the initiative was to create an incubator for beekeeping. The detailed goals include promotion of the region and increasing the awareness of local bee products, goldenrod honey from the Skrzyszów Commune located on the List of Traditional Products in the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, strengthening cooperation between apiaries in the commune and the Tarnów district and creation of a bee trail or Honey Land within the Skrzyszów commune and the surroundings of the incubator.

The planned activities include introduction of paid statutory activity and then simultaneously performing economic activity in order to create a beekeeping incubator in the area of the commune. The problem is also the lack of funds to adapt the building and transform it into an incubator. The incubator in which to conduct activity related to the production of food of animal origin is subject to registration and approval by the territorially competent authority of the Veterinary Inspection (district veterinarian), according to the adopted principles of the functioning of the incubator. The obligations of entities intending to conduct such activity are specified in particular by the provisions of Articles 19 and 21 of the Act of 16 December 2006 on products of animal origin (obligation to draw up a technological design of the establishment and requirements concerning the application for entry in the register and for approval of the establishment), depending on the manner of use. Approval is granted on the basis of an inspection of the establishment by an employee of the competent district veterinary inspectorate, during which compliance with hygiene requirements is evaluated. Hygienic requirements for such establishments are defined in Regulation (EC) No 852/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the hygiene of foodstuffs. The problem is also related to the necessity of meeting the requirements indicated in Regulation (EC) No 852/2004, which does not regulate certain requirements precisely, but contains vague terms such as “premises allowing for proper maintenance, cleaning and disinfection”. One of the main limitations was also the issue of legal regulations and the possibility of starting this type of incubator.

It has been agreed that the incubator can be made available on the market for the purpose of processing food, in this case—honey. The incubator can be made available to local beekeepers for the purposes of processing food provided from the farms—for processing honey, using the service of making the incubator’s space and equipment available. Thanks to the actions taken and the solution found concerning the sanitary and epidemiological requirements, the club realized it can make efforts to obtain funds for launching the investment. The incubator is planned to become a place where advice on honey processing technology and beekeeping is available. Moreover, it is to be an area for meetings and exchange of experience between beekeepers and producers.

Taking into account the volatility of the real estate market and all the components of the venture, after a long analysis the decision has been undertaken to lease a building with a total area of 107.72 sqm in Szynwałd for 25 years from the commune of Skrzyszów, in order to renovate and adapt it for honey processing and conducting trainings and hosting study groups. Obtaining funds for the creation of the incubator from the Civic Organisations Development Programme or Małopolska Bee Programme is also planned. Then, the funds for the maintenance of the building are planned to be obtained from paid statutory activities, donations, and membership fees. Launching the incubator is a response to the defined problem of the lack of possibilities for the legal processing of honey and its further distribution within short supply chains, as previously indicated. The realization of this task will be a tangible institutional support to improve the club’s premises, working conditions, and comfort, and to improve the image.

The intention of idea givers is to increase the awareness of potential customers (in and outside the region) about the local products, which would directly translate into the promotion of the region and the commune as bee-friendly. The thematic village (commune), as in the case of Bałtów, has great opportunities for development. The identified internal stakeholders of the initiative include beekeepers club and Skrzyszów commune, whereas the external stakeholders are local beekeepers, potential clients (both local people and tourists visiting the region), individuals, families, seniors, and children.

The initiative is addressed to two target groups. The first one consists of small apiaries, which thanks to the incubator will be able to legally marketize honey. The project will improve their economic situation (thanks to the possibility of selling the products) and will contribute to the increase of cooperation between the apiaries, creating a beekeeping community around the club and underlining the benefits of cooperation. The second target group consists of the potential customers, including tourists visiting the region and buying honey or other bee products such as honey, bee pollen, feather, and royal jelly as gifts for their families or friends. The main aim of the activities within this group is to promote the region and local honey by offering products of the highest quality.

4.3. The Case of Szklana—Village Community Center: “Kamieniec as Our Place on Earth”

The village of Szklana is one of the smallest villages in the Proszowice municipality (Southern Poland—No. 3 on

Figure 1 within the Malopolska region) with an area of 75 sq. km and a population of about 120 inhabitants. It is a village whose buildings are located mainly along the provincial road no. 776, in the north-eastern part of the Lesser Poland Province. Szklana village is a typical agricultural area, where people have been making their living by working on the land for generations. However, due to social and economic changes, a significant number of younger residents of the village decided to take up professional jobs in recent years, mostly in Krakow. The change of environment and surroundings, however, helped to perceive the value of local tradition and the need for strong interpersonal ties. As a result, the Village Housewives’ Club (KGW SZKLANA) was reactivated in the village, and so were the village grounds—called “Kamieniec” (2.14 ha)—as a place of local initiatives and meetings of inhabitants.

The main problem of Szklana, as identified within the observations and interviews, is the lack of a village hall that would serve the local community in the form of: organizing activities for inhabitants, mainly children (up to 15 years old), youth (15+), seniors (60+), organizing of free time activities (educational, physical development, sports), conducting village meetings and integration meetings as well as creating a seat for some local social organizations operating in the village. An additional problem is the development of the village area, “Kamieniec”, in accordance with the expectations and needs of residents, creating an attractive place for recreation and outdoor recreation for whole families. The above-mentioned problems are reflected in the social (article on KGW SZKLANA, “MojaWieś” portal, etc.), press (April issue of “Tygodnik Poradnik Rolniczy”). The problems were also raised on numerous occasions at village meetings with the participation of representatives of the commune authorities and at sessions of the Proszowice Town Council.

The main goals to overcome problems it to create a village common space in Szklana village in order to launch educational, sports and integration activities and to develop the “Kamieniec” grounds.

Among the internal stakeholders, there are members of the Rural Housewives’ Club (KGW) in Szklana (18 people), who manage “Kamieniec” and lease the adjacent land from the commune, were identified as project implementers. The KGW club has legal personality and has already implemented several grant projects, which were obtained, among others, to plant shrubs to protect the slopes of “Kamieniec” from natural erosion. Additionally, the mayor of the village, the councilor of the district and the municipality have shown intentions to be involved in the project. Some additional external stakeholders of the project have been indicated as primarily residents of the village Szklana, but mainly children (30 people), youth (20 people) and seniors (15 people). Additionally, families from neighboring villages and the town of Proszowice might also benefit from the project as they may gain an attractive area for active recreation. The proposed initiative is mainly addressed to the inhabitants of Szklana village (c.a. 120 people), the inhabitants of the neighboring villages (c.a. 200 people) and the town of Proszowice (c.a. 1000 people). Main target groups of the project are children (9–15 years old), youth (15+) and seniors (60+).

The project added values include: creation of a village common space and its identification as a place friendly to people and the environment, connecting and integrating village residents, headquarters for local social organizations and facilities for their activities, possibility of conducting educational, sports, culinary and artistic activities for children, teenagers and seniors, making village life more attractive, improving life in the countryside, emphasizing the landscape and tourist values of the place, promoting local history of the village and “Kamieniec”, revitalization and reclamation of the former stone mining site, innovativeness of the form and applied solutions. The implemented project is regarded as the possible model of good solutions and practices that can be used for adaptation of other rural areas with similar potential in the whole country and other countries.

Among the human resources crucial for the project realization there are members of KGW Club, including the president coordinating the project, construction workers and construction works manager, construction supervision workers, pedagogues and kindergarten teachers, counselors possessing knowledge on possible sources of project financing, representatives of the commune and the head of the village—acquiring necessary permits and notifications. Among the internal stakeholders listed, the human resources with indicated and required qualifications are members of the KGW village club.

On the other hand, the material resources to be managed include the area of “Kamieniec” and the adjacent field to be developed, as transferred in the statute as municipal property for the purposes of the village, and the adjacent area was leased for 10 years to KGW Club.

Among the activities to be taken in order to fulfill the initiative’s objectives, the following have been identified: identification of residents’ needs, administrative tasks (obtaining required permits, preparing plans), project promotion, preparing the ground for setting the dayroom and installation of containers, finishing and furnishing the interior, planting and arranging the surrounding area, creating a mini playground, launching and conducting classes, project coordination, and accounting for the project and evaluation.

5. Discussion

Discussing the first initiative: the main problem identified in this area was lack of market opportunities, i.e., creation of a market, or what was not explicitly stated—insufficient market and lack of sufficient potential for its building in the closest vicinity. Apart from the fact that in the presented case little emphasis is put on specifying the market, another important thing is the identified (and therefore noticeable) lack of promotion—knowledge and assortment of local products in the area. Such rural specificity is not limited to the presented case, as this seems to be rather common in other EU regions—insufficient promotion of local products.

The initiative to establish a foundation is directly in line with the smart village idea, where local actors take the place of initiators of development projects. Another element, resulting from the specificity of the initiative, is the concentration on the promotion of production and sales of the locally unique product, which is wine, is consistent with the idea of intelligent regional specialization, where the assumptions include identification and strengthening of unique regional and local products and activities, specific and culturally justified. This is justifiable, among other things, by the prospects for the development of the initiative in the immediate local, but also further regional environment. Among the noteworthy factors resulting from the description of the initiative, the one that stands out, in addition to the perspective of regional development, is the offer of electronic sales, such as an online store, as the third stage.

In problem solving: among the stakeholders identified by the idea-givers, practically only the municipality was indicated as internal, while the external stakeholders were noticed only in the local environment, not going significantly beyond the immediate region.

The introductory analysis of the local initiative allows us to assume the lack of any supra-local perspective in the phase of conceptualization. However, it can be observed that there exists a local group that cares about the development of their region, which is in line with the smart village idea [

1].

Stakeholders from the city are noticed much wider in the implementation phase of the initiative. Then, the potential of the solution as a model for implementation in neighboring municipalities is recognized, and the development and acceleration in the long run only gives the possibility for municipalities and cities themselves to get involved. Direct perception of the importance of urban partnerships is therefore evident in the implementation phase of the initiative. In the context of perceiving their presence at the stage of problem and conception of the initiative, such presence can only indirectly be indicated to a small extent.

In the second presented case, “Beekeeping incubator”, which in the context of smart villages is referred to as using local amenities [

26], the main identified problem seems to be low industrial capacity in relation to processing, or more industrial approach to the local product, which is honey. In order to cope with this problem, the concept of incubator was initiated, which should rather refer to the creation of a kind of social cooperative, a place where industrial goals would be realized, which finds reference to planning in the concept of smart village [

20]. Despite that, however, there are references to the functioning of the incubator in the presented initiative, such as its specificity. Among them, one can notice obtaining advice on honey processing technology, as well as networking activities. The identified stakeholders include the municipality of Skrzyszów (internal stakeholders), while the identified external stakeholders do not include any other supra-local groups, institutions, or individuals that could affect the implementation of the initiative. On the other hand, in the earlier broad description, references to sanitary regulations, legal acts referring to food regulations are made in a very specific way, which suggest that supra-local groups or institutions, e.g., those that are district or voivodeship, may have a very significant impact on the implementation of the discussed initiative. Therefore, at the level of identification of urban partners, there is a direct lack of perceived participation, as well as at the stage of conceptualization. It should be noted, however, that indirectly at the stage of partners identification their presence can be noticed, taking into consideration the issues of incubator localization. In the conceptualization phase the participation of municipal partners is also not very directly visible, but already indirect references to the location and legal regulations give an indication of the need for partnership at the level of at least consultation. In the context of implementation, where identified sources of financing in the form of EU funds are mentioned, it seems that both direct and indirect relations with municipal partners are necessary.

As far as the third case is concerned, the described initiative affects an area with slightly better characteristics in terms of entrepreneurship level than the first two cases. Nevertheless, it is still an area with low entrepreneurship saturation and a small number of functioning NGOs (

Figure 3). The presented initiative, unlike those presented earlier, should be qualified only as a social innovation, as it lacks any benefit dimension. Instead, the idea of creating a dayroom fits into the leisure industry, which has a profit-generating dimension, but not in relation to “Kamieniec”. Thus, the initiative fits into the domain of the so-called growth centers [

25,

26]. In the issues underlying the goal of the initiative, the initiators mention the economic migration to the city (Kraków), but what is also highlighted is the issue of newly arrived inhabitants of rural areas. The need to organize leisure time is accompanied by the need to integrate communities under the banner of upholding tradition. Therefore, it seems that in the context of the discussion on the community center initiative, the problem of partnership is indirectly perceived, but it has a social foundation—it concerns the social fabric, namely the tightening of social relations between the existing and new rural inhabitants. The external stakeholders included local representatives, while the beneficiaries who should also be counted as external stakeholders included those from the nearest urban center. It should be noted, however, that these are only indications of people who will use the community center and its offer in the future. In the context of the developmental concept itself, which is reflected in the smart village concept [

20], it is possible to identify at the level of the problem the participation of the city, as it is indicated as a source of information, and meetings of inhabitants with administrative authorities at different levels, including municipal, but also district ones.

As a result of the analysis of the three innovative development concepts, it can be indicated that partners from urban centers are hardly identified by idea-givers (Q1), thus both their influence on the creation of development concepts (Q2) as well as their impact during the implementation of these initiatives (Q3). The initiative concepts presented in two cases were socio-economic in nature and in one case purely social. While the conception in which economic objectives were indicated lacked any direct identification of municipal partners among the stakeholders, in the case of the purely social conception there was a reference to the municipal authorities of Proszowice and the residents and employees of the city of Kraków. Therefore, stakeholders from closer and further surroundings of the city were identified, but only in relation to Proszowice can we talk about a potential partner role considering indications of reporting problems occurring in the village to this level of public administration authorities. Similarly, in the case of this one social initiative, we can discuss the indirect participation of municipal stakeholders. It seems that in two other cases, although there is no direct reference to municipal stakeholders, their influence on the conception (Q1) as well as on the implementation (Q3) can be seen in the descriptions, though to a small extent. In case of the beekeeping incubator initiative (Case no 2) the need for active participation of supralocal stakeholders was not directly indicated, however, it seems, based on the description of the issues related to the implementation of the incubator, that such participation would be necessary, if not indispensable, and therefore the active role of these stakeholders, and thus partners, is desirable, if not necessary. Therefore, in this case we can consider the impact (Q2) on the creation of initiatives as small, but the impact (Q3) as at least moderate.

Table 2 presents the results of the analysis and evaluation of three innovative rural development concepts from the point of view of:

- (a)

Identification of urban partners in these concepts (Q1);

- (b)

The influence of urban partners on the creation of development concepts (Q2);

- (c)

Possible impact on the implementation of the initiatives (Q3).

What was not presented in the initial assumptions of the work and what should be treated as recommendations resulting from practical implications is the level of perceiving the role of urban partners. In the descriptions of concepts, indirect reference to those active stakeholders can be seen, mainly in the layer of implementation of initiatives.

In the described cases of village development concepts, which refer to modern smart village concepts, the need for partnership at the planning stage either does not exist or is indirectly noticed to a small extent. This allows us to identify the big future potential for the smart village expansion and development, which in terms of rurality in regional context can be extrapolated EU-wide. However, the closer the concept approaches the implementation phase, the more the importance of urban partners increases. This implies the need to establish rural-urban relations already at the planning stage, the stage of conceptualization of solutions aimed at building smart villages, in this case in Małopolska.

When analyzing the state of urban–rural partnerships, it is important to recognize that the definition of rurality varies regionally as a result of different degrees of urbanization, settlement types, and landscapes. In addition, European countries differentiate in terms of their level of metropolization, which in turn determines the spatial scope of practical cooperation and theoretical investigation, which in turn may result in a different perception of the definition of partnerships even if it is made more specific. The concept of urban–rural partnerships therefore needs to be adapted and adjusted to local needs and conditions [

42]. It is essential to identify the barriers that hinder the establishment of cooperation, as well as the potential benefits that various types of entities in both urban and rural areas could derive from partner cooperation. The basic questions that arise in this context are who could initiate such cooperation, in which thematic areas it could have the greatest significance and on what level it should take place. The added value of cooperation is not always recognized by local stakeholders. The formation of urban-rural partnerships, although often treated as a tool to achieve the objectives of territorial cohesion policy, should not be seen as an alternative to existing solutions but rather as a complement to them. Another point to be made when considering the potential and appropriateness of urban–rural cooperation precisely concerns the objectives, which include not only development in economic terms but also in social and institutional terms. The initiation of urban–rural partnerships in the Polish context has a regional dimension, a greater level of involvement in this field is attributed to regional authorities [

42] in comparison with European regions (the example of the Netherlands) where the party initiating and expressing interest in cooperation are metropolitan authorities. The case of Poland is an example of competition in the pursuit of funds for local development, where city authorities perceive the province as competition. Unfortunately, a similar approach does not lead to territorial cohesion [

32].

6. Conclusions

The aim of the study was to assess the role of partners from urban centers in the concepts of local development of rural areas in order to find the potential for future cooperation. The aim of the study was not to indicate the size of the city, it was more to identify the place of supra-local partnerships in rural development concepts. In order to be able to achieve the aim of the study, three research questions were formulated relating to whether urban partners in development concepts are identified at all (referring to the assessment at low level), how big a role these partners play and how strong their influence is in the planned implementation of these concepts. Innovative development concepts for social development and economic development were taken into account. The method that was used to investigate the problem is a critical analysis of the literature and explanatory multi-case study analysis.

The growing importance of the role of cities in the economy finds very strong evidence in the literature. It is accompanied by depopulation of rural areas, where inhabitants are less able to use urban resources than the urban-born population. This concerns the housing market and health services, but also, among others, services related to the leisure industry. A lower level of adaptability of inhabitants of rural areas in cities is accompanied—opposite to the reverse—by a lower level of adaptability of inhabitants of cities in rural areas. The trend of moving from cities to areas with lower levels of urbanization is noticeable and also observable among researchers. As in the case of the need for an adequate approach to the management of agglomerations and areas with a high level of urbanization (smart cities), it is also important to manage areas with a low level of urbanization (smart villages) in accordance with the changes occurring in the economy. Local resources are important in the implementation of smart villages, but also the transfer of knowledge, particularly from urban centers where development and innovation concepts are related to the functioning of knowledge centers such as universities. Successful implementation of the idea of smart villages, despite their limited knowledge resources, depends on local and regional cooperation with stakeholders from closer and further surroundings, especially centers with a higher level of urbanization.

Thus, the role of partners from urban centers is crucial, both at the stage of conceptualization of innovative products and services, as well as in the process of their implementation. Considering the indispensable factor of knowledge transfer in the realization of the concept of smart villages, support from stakeholders at the supra-local level should be recognized as necessary. However, the reverse migration, i.e., from cities to villages, seems to be a factor that may constitute, if not a solution, then a significant progress in the realization of the concept of smart villages.

The analysis of the three presented cases seems to confirm the conclusions of the literature analysis. The development concepts identified as part of the idea of building intelligent villages find reference to stakeholders from urban centers. This presence is less directly noticeable at the stage of creating innovative concepts, but much more significantly at the time of planning the implementation of innovative solutions. The analyzed rural areas, which are characterized by a particularly low level of saturation with profit and non-profit oriented organizations, and therefore those for which smart and intelligent development is particularly important, should naturally open up to knowledge and transfer it from urban centers.

Therefore, considering the results of the conducted research, deliberations, and discussions in the context of assessing the role of partners from urban centers in development concepts in rural areas, it seems that in the context of Poland, and Malopolska in particular, the role of those partnerships is perceived and realized, but the potential for future collaboration is huge. The importance of the need for partnership is hardly noticeable during the very creation of development concepts, which allows us to prioritize the policies of building concepts to innovate in order to increase the smartness of villages and to engage to a great extent the stakeholders from cities. The described cases focused on areas with low saturation of economic and social organizations, which may explain such a low level of inter-partner relations, thereby pointing out directions for further research. There is a need to study cases from areas with higher levels of social and economic entrepreneurship.