Abstract

Like other countries of the world, Costa Rica faced the challenge of dealing with a variety of trade-offs when implementing sustainability goals in agriculture. Very often, economic promotion is in conflict with goals regarding human and environmental health protection. Organic farming practices could provide strategies to overcome some of these trade-offs. However, in Costa Rica, the majority of farmers still relies on conventional farm practices. In this paper, I investigate the potential for a sustainable transformation in Costa Rica’s agriculture by focusing on organic farming policies. I shed light on the role local actors and organizations play in this process compared to other actor types. I argue that local actors are “the agents of change” in these processes, as these are the target groups of organic farming policies and are the ones who are asked to change their farm practices. Based on survey data and network analysis, I was able to illustrate how differently integrated local actors are compared to other actor types in Costa Rica’s implementation of organic farming policies. Local actors show interest and willingness to further participate in land-use implementation processes when institutional barriers are alleviated, and further promotion instruments are available.

1. Introduction

Costa Rica made international headlines with its detailed plan to decarbonize its economy by 2050 and thus takes a further step as a global green pioneer [1,2,3]. The Central American country already has a strong basis of environmental protection as it started early with investments into ecological preservation and its social system and is now well known for its efforts towards sustainable development [1,4]. However, in one aspect, the country is not environmentally performing so well: Its usage of pesticides in agriculture is one of the highest in the world [5,6]. Costa Rica imported 2648 tons of pesticides in 1977. This more than quadrupled by 2006 to 11,636 tons [7], with associated serious risks documented for the environment [8,9,10] and human health [11].

In terms of sustainable development, the high use of pesticides poses a particular challenge also because Costa Rica’s economy and farmers’ income are dependent on the cultivation and export of agricultural products, and pesticides are used to guarantee a more or less stable harvest [12]. One possible way to combine economic growth with ecological and social protection and thus overcome sustainability trade-offs is organic farming. Organic farming is a production management system that applies environmentally friendly methods of crop and weed control. It uses natural sources of nutrients, such as compost, crop residues, and manure “which promotes and enhances agro-ecosystem health, including biodiversity, biological cycles, and soil biological activity” [13], and the use of synthetic agrochemicals is forbidden.

Important steps towards the national implementation of organic farming practices in Costa Rica include the creation of the National Chamber for Organic Exporters and Producers (CANAPRO) [14] and the introduction of a new program for organic practices by the National Institute for Apprenticeships (INA) in 2017. Moreover, Law No. 8591 for the Development, Promotion, and Facilitation of Organic Farming (published in August 2007) and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC (published in November 2009) were designed to promote organic farming practices in Costa Rica. However, ten years later, in 2019, Costa Rica only had an area of 8832 hectares of organic agricultural land registered, which is a share of 0.5 percent of total agricultural land [15]. In 2008, there were 8004 ha of organic agricultural land in Costa Rica [16], indicating a slow growth of organic agriculture. The fear of high economic costs—especially during transition periods—has been mentioned as a contributing factor to the lagging trend. Galt [17] also cites the underrepresentation of environmental activists, local actors, and NGOs in its implementation process.

The literature on collaborative governance and the management of land and natural resources largely emphasizes the roles of local actors and target groups and sees them as fundamental in the design, formulation, and implementation of land-use-related policies [18,19,20]. Local actors are often directly addressed by policy instruments and practices and thus can benefit from (or be disadvantaged by) related decisions [20,21].

Organic farming challenges the responsibility not only of the government to steer but also of producers and consumers to change their behavior [22,23]. The ways different types of local actors are integrated into organic farming policies, with a particular focus on local organizations, is worthy of study. In this context, the following research questions arise: How are local actors involved in the implementation process of organic farming policies in Costa Rica, and how does this differ from the integration of other actor types?

I answer these questions by focusing on the implementation process of the aforementioned organic farming law and its regulation. I gathered data through actor and stakeholder surveys and conducted a social network analysis that informed me about the degree of inclusion in the implementation of various types of actors. After some conceptual thoughts, I present an overview of the situation along with the data, results, and analysis. I sum up with insights into the process under study but also come to some broader conclusions about the role of local actors in general and about the implementation of organic farming, in particular.

2. Local Actors in a Multi-Level Perspective

Sustainability challenges a variety of systems, such as the food and energy systems, and calls for more or less fundamental societal transitions. To guide such large transition processes, the literature relies on governance concepts and, thus, steering mechanisms that are designed and implemented by a network of public and private actors [24]. Many challenges are disentangled in space and time, such as climate change sources and their impacts and the production and consumption of diverse goods and services [25]. Such problems, which include the use of pesticides or the implementation of organic farming, are often perceived differently depending on the level they are viewed from, with the consequences of environmental issues being particularly felt at the local level. In addition, in order to assure proper application standards, regulations regarding social and environmental impacts are often set in non-hierarchical structures [26]. Likewise, network structures and multi-level and cross-sectional perspectives are essential in the examination of how actors are integrated into natural resource management and the implementation of sustainable development policies [20,27,28]. Indeed, it is very common that multiple public and private actors “engage in international standard-setting processes” [26] (p. 1) for nearly all kinds of environmental issues, such as certifications in agriculture, fishery, forestry, and maritime on a local, national, and global level.

Land-use policies constitute a good example of how governance structures influence policy implementation because responsibilities and tasks are typically shared and, at the same time, difficult to control. Indeed, multi-level governance strategies are often pursued to improve the management of complex issues, including land use and natural resource policies. In this respect, scholars point to possible issues related to learning and the efficient dissemination of knowledge in governance systems [29]. For example, it is essential for high levels of government to have very detailed information about local issues (e.g., urban and rural communities each face different challenges [30]), and to consider that developments in one sector can affect other sectors substantially (e.g., the growth in large-scale farming can affect the tourism sector due to changes in the landscape). Schweizer et al. investigated the implementation of the Forest and Landscape Restoration (FLR) policy, which “aims to regain ecological functionality and enhance human well-being in degraded landscapes” (p. 1) and underlines the importance of local knowledge, and thus the integration of a variety of actors, in order to include scientific as well as tribal and practical knowledge [31]. Moschitz et al. explored the network dynamics of the organic farming policy in the Czech Republic and found that over a 10-year period (2004–2014), the dynamics in the policy network changed substantially. The network centralized around the national Ministry of Agriculture, although it was initially mainly influenced by organic sector organizations. However, according to the authors, the organic farming organizations maintained their reputation for being valuable contributors to organic farming policy [32].

More general literature on sustainability issues often takes an actor-specific perspective, and in the case of climate change adaptation, which includes the governance of natural resources like water or land, vertical integration is often considered crucial [33]. Ziervogel et al. describe vertical integration as a “process of creating intentional and strategic linkages between national and subnational levels” [34] (p. 2729). In other words, vertical integration provides opportunities for coordination between supranational, national, regional, and local levels [35,36]. The literature highlights local actors as essential elements for climate change adaptation, stating the integration of local groups should be promoted [34]. Likewise, recent literature on energy transition often concentrates on the role of local and civic actors, and scholars widely agree that, among other factors, their inclusion is a central aspect in the transition to renewable energy [37,38]. Nabiafjadi et al. [39], who conducted an empirical network analysis in the Middle East about water governance, emphasized the need to decentralize administration to local, private, or non-governmental actors in order to improve water governance [40]. Hegga et al. went one step further, examining what actual capacities local actors—who seem to be already integrated into the implementation of policies through decentralization in water services—need in order to successfully participate in the operation and management of water services [41]. According to their research, the allocation of sufficient resources to the local actors is essential to ensure their successful and efficient participation in such governance systems [41]. Numerous studies emphasize the role of local actors in multi-level governance settings, and various scholars point out the important role of formal rules regarding horizontal and vertical integration to guarantee the inclusion of different types of actors in policy design and implementation [20,42,43]. According to Ingold [20] (p. 2), in governance structures, particularly “formal rules are defined to enhance the vertical integration of actors”.

In governance structures and land use policies, such formal rules can be based on the design of implementation processes. Here, the literature distinguishes between the “top-down” (e.g., [44,45]) and the “bottom-up” (e.g., [46,47,48]) approach. While the former starts with policy decisions made by authoritative policy statements or by governmental officials and “proceeds downwards through the hierarchical administrative structure to examine the extent to which the policy’s legally-mandated objectives were achieved and procedures followed” [49] (p. 12), the bottom-up approach begins at the local level and tries to include all actors who are affected by a policy from the beginning of policy processes [50]. For instance, Pachoud conducted a case study of a regional policy called Territorial Pastoral Plans (TPP) in Rhône-Alpes (France) that was considered innovative regarding “the territorialization of public action in favor of pastoralism, by articulating sectoral and territorial policies through bottom-up forms of governance” (p. 2). Focusing on the implementation process of TPPs, the author revealed that “this policy has provided the conditions for a pragmatic territorialization of public action by offering local actors an alternative and open form of governance within self-determined pastoral territories” (p. 11). However, Pachoud claims that such programs need more attention in agricultural policies, which mostly follow a top-down logic [51].

For this study, I use the distinction between top-down and bottom-up policy implementation to identify the independent variable, which is the formal rule regarding the implementation of organic farming in Costa Rica. Concretely, I examine whether Law No. 8591 and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC on organic farming in Costa Rica use a top-down or bottom-up implementation design. In sum, the assumption that the implementation process of Law No. 8591 and Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC is top-down serves as the independent variable.

Formal rules, such as the top-down implementation design, can affect the collaboration or reputational role of different actors. Actors are considered strongly integrated into a network when they collaborate with many other actors. For example, if local actors are considered important, they have high reputational power in the network. Moreover, if local actors collaborate with various national and global actors, their integration in the network is strong. Thus, they could access resources and participate more actively in policy implementation processes (see also [52]). This leads to the first and second hypotheses guiding this research:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The top-down implementation of Law No. 8591 and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC causes little reputational power of local actors in the implementation process.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The top-down implementation of Law No. 8591 and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC leads to limited integration of local actors in the implementation process.

In addition to the important role of local actors in policy processes, which is especially addressed by research into natural resource management and land-use studies, it has been widely agreed that the integration of different actors who represent different interests and stakes is necessary to manage complex ecological systems [53]. Moreover, a diversity of knowledge can help solve issues or find innovative solutions in natural-resource governance [54,55]. Including different types of actors can provide this diversity. Actors on different levels may be underrepresented in the process when a policy has a top-down implementation design, which leads to the third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The top-down implementation of Law No. 8591 and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC causes little collaboration between local actors and national and global actors.

In land-use practices, e.g., organic farming, private actors, such as associations and organizations, can occupy an important role because they are often closely connected to target groups, such as farmers. Cooperation between the public and private sectors can increase positive outcomes, including improving the quality of the policy-making process [56]. This can be underlined by lessons from case studies about climate adaptation that suggest that such policies and implementation “requires support from a range of intermediaries including NGOs, academics, private and informal actors and institutions” [34] (p. 2740) [57]. However, the extent of the cooperation between those actor types varies across countries, depending on different structures, cultures, and systems. Scholars who investigated organic farming in Costa Rica reached the conclusion that the implementation of such policies often failed due to insufficient collaboration between private farmers, their associations, and public authorities [58,59]. Accordingly, I am interested in the integration of private actors in the implementation of the most recent policies for the promotion of organic farming and set the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The top-down implementation of Law No. 8591 and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC leads to little collaboration between the public and the private sector.

In sum, the integration of actors in the actual implementation process of Law No. 8591 and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC serves as the dependent variable, which will be explained in four different ways: (1) The reputation of local actors, (2) the integration of local actors, (3) the collaboration between local actors and national and global actors, and (4) the collaboration between the private and the public sector. The examination of a land-use policy aims to provide sustainable development and, concretely, environmental and human protection from pollution. Indeed, land-use policies are one important aspect in attaining the goal of sustainability or sustainable development due to the fact that such policies can affect food and energy security, economic growth, ecosystem stability, social justice, and, recently, the mitigation of and adaptation to climate change [30]. In addition, land-use policies can play a crucial role in accomplishing at least six of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), i.e., climate-change mitigation, sustainable use of oceans, the protection of ecosystems, access to energy, the construction of resilient infrastructure, and inclusive cities.

According to various scholars, social networks play a significant role in actors’ integration in natural resource management or, more generally, in the enhancement of sustainable development [20,52,53,60,61,62]. Actors, such as politicians, interest groups, organizations, associations, etc., represent different interests and goals. Each of these actor groups has different resources (e.g., finances, responsibilities, time, infrastructure, information, political support) at its disposal that serve its interests. Adopting a social network perspective allows studying the positions of actors and the structures of relationships within their network. The network literature adopts the concept of embeddedness in examinations of the structural integration of actors. Network embeddedness is defined as “creating intensity in actor relationships, which, in turn, influences social actions, creates opportunities and constrains actor behavior” [20] (p. 3, see also [63]). This approach is suitable for this research as it focuses on the relations (also called ”ties” [64] (p. 1–2)) between actors (also called entities or nodes) and the structures that shape these relations [27]. Therefore, both the relations between actors and the position of an actor in the overall network are important [20]. In order to study how actors are embed in a network, Freeman differentiates between degree and betweenness centrality, which measure an actors’ local embeddedness in the structural arrangement of the network [65]. The number of direct ties to other actors in the network indicates the degree of centrality [65] (see also [20,66,67]) of an actor. Betweenness centrality measures the relations of an actor with other actors who are not otherwise connected in the network [65]. Therefore, a high score of betweenness centrality reveals that someone forms a connection between pairs of actors that are not connected through other nodes [20,68]. This kind of centrality is associated with power and importance [28,65], and actors with high betweenness centrality can act as brokers, mediators, or gatekeepers [69] and are often associated with potential control and power in the network [65,70]. In sum, high degree and betweenness centralities indicate that an actor is well embedded in a network, relating to better opportunities for participation in policy implementation.

3. Materials and Methods

The objective of this analysis is to link formal rules of policy design (top-down or bottom-up) to the integration of various actors and to empirically analyze actors’ integration in the implementation process of Law No. 8591 and Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC. In order to provide an inside view into structures and processes of multi-level governance structures, I adopted a network perspective [71,72,73]. The present examination is based on a single case study with one embedded unit, the implementation process of the aforementioned Law and Regulation, which represent the most recent regulations regarding the development, promotion, and enlivenment of organic farming practices in Costa Rica. Their content suggests the intention of including multiple actors in the implementation process of organic farming since special tasks to implement the law are assigned to many different actors (see Appendix A, Table A1). Moreover, a new department (namely the Departamento de Fomento de la Producción Agropecuaria Orgánica) was established at a national level within the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (MAG) to guarantee the effective implementation process within a few years of its publication.

3.1. Study Area and Case

Costa Rican agriculture, with its high pesticide use combined with genuine efforts towards environmental protection and sustainable development, is well suited for this research, which seeks to identify the possible factors that are influential in the slow implementation of the land-use policy of organic farming.

With the aim of investigating the vertical and horizontal integration of actors in the implementation of the aforementioned law and regulation, I selected the canton of Zarcero for this research project due to its typical rural characteristics, which are very suitable for the examination of land-use policies. Zarcero is located in the north central Alajuela province of Costa Rica and has a population of 14,624 inhabitants (2022), of which about 67 percent live in rural areas [74]. The average years of schooling are 7.4, and the literacy rate is 97.7 percent. Data from the National Census of 2011 show that 39.6 percent of the economically active population works in the primary sector (including agriculture, livestock, forestry exploration), 15.8 percent in the secondary (e.g., industries), and 44.6 percent in the tertiary sector (e.g., trade, transportation, education) [75]. The canton, which has an area of 155.13 km2 and an average altitude of 1769 m asl., can be considered a mountain climate with an average temperature of 17 °C, and is characterized by agricultural practices. Some farmers apply organic farming, but a large part of the canton is dominated by conventional farming practices, with associated use of synthetic pesticides [76,77].

3.2. Defining the Network Boundaries

As mentioned above, the integration of actors in the implementation process is the dependent variable and will be explained in four different ways, namely (1) the reputation of local actors, (2) the integration of local actors, (3) the collaboration between local actors and national and global actors, and (4) the collaboration between the private and the public sector. In order to operationalize these variables, a few preliminary steps were required. I relied on the classic combination of the positional, decisional, and reputational approaches to identify all (collective) actors involved in the present implementation process and thus, define the network boundaries. Because of the fact that in today’s politics, collective actors, such as public or private organizations, authorities, associations, agencies, or universities stand in the spotlight [60,78], I only identified collective actors, not individuals. Finally, these identified actors form the network under investigation, defining the network boundaries (see also [79]). First, following the positional approach, all actors who have a formal assignment in the implementation process and were therefore mentioned by name in Law No. 8591 and in Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC were identified. Second, further actors who were formally involved in the implementation process were determined following the decisional approach by conducting literature research and interviewing two key actors of the policy-making process—one representative from the Phytosanitary Service of the State (SFE) and one representative from the National Organic Agriculture Program (PNAO) of the MAG. Lastly, following the reputational approach, an interview with one organic farming expert from Zarcero and conversations with four local farmers (three of whom partially practiced ecological agriculture and one who solely practiced organic farming) helped me to define local actors in the canton of Zarcero. Those actors either played a key role in local policy implementation processes, are regarded as influential in environmental issues, or are considered local target groups (local farmers associations, organizations, and NGOs) of the law and the regulation.

Based on the recommendation of two actors during the survey period, I added the Regional Institute for the Study of Toxic Substances (IRET) as an actor. The result is a social network composed of 38 actors who are part of the implementation process or have been identified as essential target groups (see reputational approach, the full list can be found in Appendix A, Table A3). These 38 actors represent the reputational-power network of which I categorized nine actors as being local (24% of the total), 24 as national actors (63%), and five as global (13%). The fact that by far the largest group is the national one can be considered typical for top-down approaches, because top-down implementors often consider themselves (e.g., central/national authorities) as the key actors in the process. In contrast, bottom-up implementation typically regards the target groups (often local groups in land use policies) as the main implementors of a policy [80].

3.3. Social Network Analysis (SNA)

Applying a systematic SNA, I elaborated a survey to identify all essential actors who are actively integrated into the implementation process of Law No. 8591 and Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC and to determine relations between actors. Integration refers to involvement and participation during the implementation processes of these policies. Actors are considered integrated or embedded when they have relations with other actors, or in other words, when they collaborate with other actors, when they are consulted, or when they have decision-making power.

3.3.1. The Survey

I created a detailed survey and sent it to the representatives of the 38 actors, offering the possibilities of (1) completing the questionnaire in PDF format and sending it back, (2) meeting in person and filling out the survey together, or (3) completing it directly on the phone. Most of the actors preferred to complete the survey individually. Most of the survey data were collected during a field work period between August 2016 and September 2016, with the remainder collected up to March 2017. Some practical problems in contacting all actors were encountered at the beginning but were mainly solved with the support of local researchers. In the period from August 2016 until March 2017, a response rate of 79% was obtained (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Survey response rate (own elaboration).

Before analyzing the actual collaboration between actors in the network, I wanted to examine which actors were seen as very important by others. Through the following question in the survey, I calculated the scores of each actor’s reputational power for insight into how important they were in the opinion of others:

- −

- Please mark in the first column all those actors who are particularly important in the implementation of organic farming in Costa Rica. If actors are missing from the list, you can add them in the blank lines and also evaluate their importance.

A high reputational power score means that an actor is considered important, therefore would be considered well-integrated into the reputational-power network. For example, actors on the national or global level might consider local associations as very important for the implementation of organic farming policies, even if they do not collaborate directly with them.

As mentioned, collaboration relations seem especially relevant in investigations into actors’ integration in the organization of implementation processes [69]. Therefore, the collaboration between actors was used to analyze the integration of different actor types in the implementation of the aforementioned organic farming policies. The second dependent variable, i.e., the integration of local actors in the implementation process, is analyzed through the following question regarding the collaboration of all actors:

- −

- Please mark each organization or institution with whom you have regularly collaborated since 2009 in questions of organic agriculture and, more precisely, in the implementation of Law No. 8591 and its corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC. With regular collaboration, we mean a repeated exchange of information or joint performance of projects. If actors are missing from the list, you can add them in the blank lines and also mark possible collaboration.

I used the answers to this question to create the collaboration network. To obtain an overall picture of the situation, indegree, outdegree, and betweenness-centrality measures were used in the collaboration network.

The data for the third dependent variable concerning the collaboration between local actors and national and global actors were obtained from the following question regarding their geographical position to define the level at which each actor works.

- −

- Please specify for which area your organization in the field of organic farming is formally in charge, which includes regulatory, implementation, and consulting expertise. District, canton, province, region consisting of the following municipalities/cities, entire Costa Rica, cross-border region, or other.

According to those answers, I assigned each actor an attribute as to whether they operated on the local, national, or global level and assigned them to the corresponding group. By applying the within- and across-group density measure, I was able to measure the density between groups.

The fourth dependent variable, namely the integration of actors from different sectors, is measured by their density in the network. This follows the same principle and method as explained above in the cooperation between actors at the local, national, and global levels: The same list of actors was divided into actors operating in the private sector and actors operating in the public sector. The public sector group is composed of actors who are connected to the national government and/or depend on it, whereas the private sector group consists of private associations, NGOs, public universities, and research institutes because they are generally independent of the national government (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Assignment to levels and sectors of actors in the collaboration network (own elaboration).

3.3.2. Centrality Measures

Different centrality measures were used to analyze the embeddedness of local actors in the implementation process of organic farming. Data were examined with the help of UCINET v.6, software for the analysis of social network data [81]. A high degree of centrality score, defined by an elevated number of ties with others in the network, indicates that someone is structurally well integrated. Within this centrality measure, indegree and outdegree offer further insights into the social network. While indegree centrality offers a score regarding an actor’s popularity, outdegree measures the activities of an actor in the network. Concretely, applying these centrality measures provides a picture of who is popular and who is active. A high betweenness centrality score indicates an actor who is a broker in the network or who acts as a mediator or gatekeeper. Without such actors, the network would fall apart or would not even exist (Lienert et al., 2013). Gould and Fernandez (1989: 95) refer to Bavelas (1948) and Freeman (1977, 1979), who claim that betweenness centrality is “a natural way to measure brokerage.” As mentioned above, in a network, brokerage is often connected to power and powerful actors, but it is also linked to integration.

Furthermore, I measured the collaboration between different levels on the vertical axis through within- and across-group density. I relied on Ingold’s definition [20], which defines density as “the number of observed relations in the network divided by the maximum potential relations possible” (p. 5). Thus, I obtained a density score within and across the local, national, and global groups by counting how many relations the different groups share with others and dividing this number by the maximum potential relations. I also measured the collaboration within and between the public and private sector through within- and across-group density.

To overcome the issue of sample non-independence related to network data [68], I conducted statistical tests, namely T-test, one-way ANOVA, and Relational Contingency-Table Analysis statistical test, in UCINET (v.6, [81]), which includes bootstrap routines in its hypothesis-testing programs and provide insights about the significance of the results.

4. Results

The assumption of the independent variable, namely that Law No. 8591 and Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC follow the formal rules of top-down policy design, was confirmed by the following aspects: First, during the analysis of the law and the regulation’s content, I identified 34 actors who are mentioned and (partially) assigned concrete tasks in the implementation process, 32 of whom work on the national level (a list of all mentioned actors can be found in Appendix A, Table A1). Second, only national authorities (e.g., PNAO, which is part of the MAG) participated in drafting the law and the regulation. Third, in an interview with the representative of the PNAO, it became evident that local actors or authorities did not have the opportunity to participate in formulating or implementing the law or the corresponding regulation. Lastly, evaluating government protocols provided by the PNAO regarding the first and the second debate in the parliament concerning Law No. 8591 (a list of all actors participating in these debates can be found in Appendix A, Table A2) strengthened the assumption that Law No. 8591 and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC were implemented through a top-down implementation process.

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

I created the collaboration network based on the actors that responded to the survey. I excluded all actors who did not respond. I then calculated the degree and betweenness centrality of each node. None of the non-respondent actors (8) reached a high centrality score, confirming that their exclusion would not have a significant impact on the results. Additionally, one actor (National Insurance Institute—INS) who answered the survey marked no other actors as a collaboration partner and was not mentioned as a partner by any other actor. Therefore, this actor was excluded from the collaboration network.

Table 2 displays all actors who are part of the collaboration network, assigned to their level and sector. In sum, the collaboration network consists of 29 actors: Three at the global level, 19 at the national, and seven at the local level of the Zarcero canton.

Table 3 illustrates different network measures that present an overview of social network integration in the reputational-power network and the collaboration network. The density signifies that 33.9% of all possible ties in the reputational network exist, respectively 29.4% in the collaboration network. In addition, the overall graph clustering coefficient, which measures the average of the densities of the neighborhoods of each actor, reveals that local neighborhoods (60.6% and 49.5%) are denser in both networks than in the overall networks (33.9% and 29.4%). The network-centralization measure outdegree score shows the number of outgoing relations expressed as a percentage of the highest number possible, while the indegree score displays the percentage of incoming links. Both networks display higher outdegree centralities, whereby more outgoing ties were counted in the reputational power network. On the other hand, there were considerably more incoming relationships in the collaboration network.

Table 3.

Data and descriptive network statistics of the collaboration network (own elaboration).

4.2. Network Integration of Local Actors

Before analyzing the collaboration between actors or actor types, I examined the integration of actors in the reputational-power network. I focused exclusively on the indegree centralities of the three groups (local, national, and global) to show if local actors are considered important in the implementation of organic farming in Zarcero. Table 4 illustrates similar scores for the local and the national groups. Both are, thus, likely to be considered similarly important in the network. Global actors are considered more important as they reached the highest indegree centrality score.

Table 4.

Means in n indegree centralities in the reputational-power network (own elaboration).

These results falsify the first hypothesis that the top-down implementation of Law No. 8591 and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC causes little reputational power of local actors in the implementation process.

Applying a t-test, I compared the mean centrality of the local actors to all national and global actors in the network. In addition, via one-way ANOVA, I evaluated whether the differences found in group means (local, national, and global) were significant. None of the tests were significant, which is most probably because of the low number of observations.

Moreover, to measure the structural integration of local actors, in particular, I relied on indegree and outdegree centralities using the collaboration network. Indeed, to confirm the first hypothesis regarding the integration of local actors, they had to obtain lower centrality measure scores in the collaboration network than other actors. As displayed in Table 5, I calculated normalized (n) indegree and outdegree centrality, which differ between reciprocal and non-reciprocal relations, i.e., outgoing and incoming ties. Both degree scores demonstrate that national actors are most active and popular in the network. Local actors are not far behind regarding the outdegree calculation, while global actors have very few outgoing ties. According to the indegree scores, local actors lay far behind national actors, and global actors seem slightly more popular than the local. The results of the betweenness centrality, which measures whether an actor lies on the path of two actors that are not otherwise connected, confirm the insights received from indegree and outdegree centrality calculations. National actors exhibit by far the highest normalized (n) betweenness centrality.

Table 5.

Means in n outdegree, n indegree, and betweenness centralities (own elaboration).

Results of the different centrality measures applied to the collaboration network partly confirmed my second hypothesis that the top-down implementation of Law No. 8591 and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC leads to limited integration of local actors in the implementation process.

Here also, a t-test and one-way ANOVA were conducted and provided similar results for the indegree and betweenness centrality as discussed above—no significance. However, the results show that the actor type has a significant effect on outdegree centrality (significance: 0.07).

4.3. Collaboration between Local Actors and National and Global Actors

To analyze the collaboration between the national and global actors with local actors in the implementation of Law No. 8591 and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC, I examined the ties and the density between actors of the three levels. In order to confirm the third hypothesis, density rates within the national and global group, as well as density rates across the national and global actors, had to be higher than density rates across the local group.

Table 6 shows the number of ties and the mean density rates within and across groups. The national group counts by far the most ties, with 122. Many ties also exist between the local and the national groups. A high density is measured across the local and the national groups (0.346). The table further reveals that actors belonging to the local group collaborate more often with actors of the national group (46 ties) than the latter collaborate with actors from the local group (28), which leads to a density of 0.211 compared to 0.346. In other words, some collaborations are non-reciprocal. Of note, I registered no ties within the global group, thus a density of 0 is measured. Members of the global group collaborated in general with very few actors. Out of 26 actors, not counting themselves, only four other actors are mentioned (two from the local and two from the national group).

Table 6.

Number of ties and mean density rates within and across levels (own elaboration).

The highest density within a group was measured within the local one (0.405), which is an indicator that local actors are very connected to each other. The local:global connection (a density of 0.429) is also greater than the national:global connection (a density of 0.228). These results confirm hypothesis three that the top-down implementation of Law No. 8591 and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC lead to little collaboration between local actors and national and global actors. However, it is important to highlight that these results reveal that local actors engage in creating connections to higher levels (national, global).

I conducted two statistical tests on UCINET [81] that included bootstrap routines in these hypothesis-testing programs. Relational Contingency-Table Analysis confirmed that the results are not random.

4.4. Collaboration between Public and Private Actors

As mentioned above and illustrated in Table 2, I divided the collaboration network into 16 actors from the public or governmental sector and 13 actors from the private or non-governmental sector. This was necessary for the examination of hypothesis four that the top-down implementation of Law No. 8591 and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC leads to little collaboration between the public and the private sector.

Table 7 shows that the density rates are slightly higher in the public-sector group. However, the private sector displays a similar density. Moreover, private actors collaborate more often with actors belonging to the public sector (56 ties) than the other way round (51 ties). Densities within each sector are higher than across those groups. However, differences are limited. The results illustrate that private actors are well integrated into the network, and looking at reciprocal ties, they are certainly very active in integrating themselves. In other words, both private and public actors more often actively look for collaboration possibilities with public actors than with private actors. These findings lead to the falsification of hypothesis four.

Table 7.

Number of ties and mean density rates within and across sectors (own elaboration).

I conducted the Relational Contingency-Table Analysis statistical test in UCINET [81] that calculated a significance score of 0.56. Thus, it gives no affirmation that the results are more significant than random. Such scores are most likely the outcome of a limited number of actors and the fact that there are only two different groups with a similar number of actors.

5. Discussion

The main focus of this article is the impact of policy design on the integration of different actors on the vertical and horizontal levels. Local, national, and global groups were included across private and public authorities and organizations, with a particular focus on local actors, due to the reasons given above. In general, national authorities and associations represent the majority of integrated actors, while some local ones also formed part of the implementation process of Law No. 8591 and Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC.

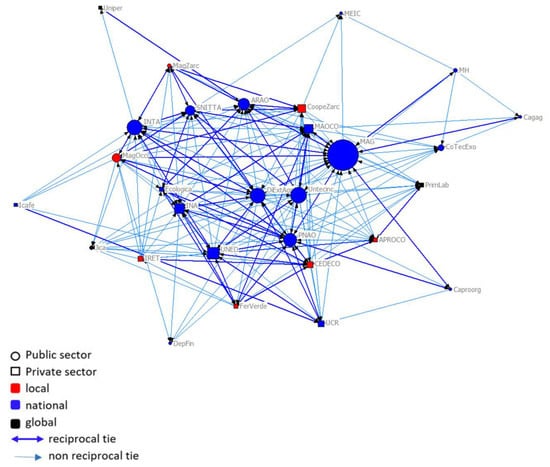

Figure 1 shows the entire collaboration network. Reciprocal ties are thick and colored dark blue, whereas non-reciprocal ties are thin and light blue. These distinctions help to illustrate a picture of the situation in the collaboration network. Figure 1 reveals that many relationships are not reciprocal, of which many come from the local and the private groups (see Table 6 and Table 7). As previously mentioned, this indicates that local actors are less likely to be considered as collaboration partners by national ones in the implementation of organic farming. Indeed, the national group certainly prefers to collaborate with actors of the same level. As a high betweenness centrality indicates the potential to play a broker role or act as a gatekeeper, and the size of the node indicates an actor’s betweenness centrality, Figure 1 reveals that especially national actors (blue) can occupy brokerage roles (e.g., the national actor MAG (Ministry of Agriculture and Livelihood). Therefore, it can be assumed that the implementation process of Law No. 8591 and Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC, which represent the legal basis for developing and promoting organic farming in Costa Rica, is mainly performed at the national level. This situation could be interpreted as one reason for the slow implementation of such laws, which target land use and, therefore, local actors and aspects, in particular. Indeed, Regulation No. 29782-MAG provides the guidelines for farmers to produce organically, how to obtain certifications for their products and is the regulatory basis of the export arrangement of organic products with the EU. National authorities are probably well informed about certification and (corresponding) export requirements, but if they are not familiar with local circumstances, they risk excluding farmers from the opportunity to consider transitioning officially to organic farming. Particularly relevant here are aspects that involve costs (e.g., for certifications), for which the law and the regulation offer very vague transitional solutions or assistance.

Figure 1.

The collaboration network (elaborated in UCINET [81]). Note: The size of the node indicates an actor’s betweenness centrality (see text and tables) (own elaboration).

The results from the examination of the reputational-power network, displaying similar indegree centrality scores for local and national actors, indicate that the local actors are considered as important as the national. This confirms the theory that local actors are important actors in land-use policies [20,52]. However, centrality measures in the collaboration network recorded a strong integration of mainly national actors, while the local group was less integrated. A closer look at the contents of the policies reveals that Law No. 8591 is more general and defines broader aspects of the promotion of organic agricultural activities, while the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC goes into more detail on many specific subjects. For example, several articles of the regulation deal with coordination with local farmers, participatory processes and consultations, or the training of producers. Both the law and the regulation seem very well elaborated regarding aspects of local implementation, with several sections emphasizing the local or regional level. Indeed, the law and regulation recognize the importance of cooperation with and the involvement of local groups/authorities and support a certain degree of governance in the implementation. However, as the results of this study show, the national actors do not make an effort to cooperate with the local organizations. In the canton of Zarcero, it is the local level that actively seeks cooperation, not the national ones. According to the law, however, the national authorities should also strive for local cooperation. Possible reasons for the poor cooperation effort of national actors towards local authorities can be manifold, but without speculating about such issues, I concentrate on a brief discussion regarding the design of the law and regulation. Both, as we have seen, had a top-down design, and local actors were only involved in a very rudimentary way. Promoting a more participatory process already in the formulation of the regulation, in this case, might have counteracted the lack of inclusion of local actors for the following reasons:

- -

- Local groups would have more knowledge about the content of the law and could promote it locally from the outset. In other words, they would not have to wait for the initiative of national authorities and thus, they could act more independently.

- -

- Relationships between locals and nationals could have been established at the design stage, thus would have already existed in the implementation process rather than having to be created at that point.

- -

- An earlier inclusion of the target group, i.e., local farmers/producers, could generally improve the acceptance of such policies, which could subsequently help to promote the implementation of organic farming practices in Costa Rica and, to that end, stimulate sustainable development.

Moreover, regarding the policy design, the content of the law and regulation could provide more details on how cooperation between organizations at different levels should look and how it can be achieved in a practical way.

In sum, Law No. 8591 and Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC acknowledge the importance of cooperation between different levels, as the regulation especially seeks to promote collaboration with local actors. However, the present research illustrated that the integration of local organizations and entities, in particular, could be improved in order to promote the transition towards organic farming as an important driver of sustainable development in Costa Rica.

Limitations and Future Research

While carrying out this research, I encountered some methodological challenges. As previously mentioned, the collaboration network consists of 29 actors and thus is a relatively small group for generalizing the outcome of this research. However, scholars have noted that “a very large part of social network methodology […] deals with relatively small networks, networks where I have confidence in the reliability of our observations about the relations among the actors” [68]. Addressing this, descriptive statistics, such as SNA provides, have proven to be of great value because they offer convenient tools to investigate and summarize “key facts about the distributions of actors, attributes, and relations” [68]. In principle, future research could include several cantons to obtain a broader picture of different local conditions.

Another challenge lies in the limited focus on only one law with its regulation. Even though the selected law and its regulation represent the legal and current basis of the development and promotion of organic farming, further policies exist that cover different topics regarding organic farming (e.g., the Organic Farming Regulation No. 29782-MAG). It could be argued that other policies addressing, for instance, pesticide use should also be taken into account in order to obtain a holistic view of the situation. For future research, I suggest including more policies on organic farming practices as well as pesticide regulations.

Regarding the results of the centrality measures in the reputation-power network that emphasized that global actors are considered to be important actors, I suggest that further studies into the implementation of organic farming in Costa Rica could focus on the role of global actors and their impact and role in land-use policies.

The last concern worth mentioning is the role of the commercialization sector and its actors in organic farming practices. Even though they did not seem to be integrated in the implementation process of Law No. 8591 and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC because they were not identified by the reputational, decisional, and positional approach and they were not mentioned by any actors in the survey’s question regarding the actors’ collaboration, such actors could, however, have an impact on organic farming practices in other ways. For instance, they can determine prices, buy more or less organic products, or promote organic products. The consideration or inclusion of those actors’ industries (e.g., the pesticide industry), political lobbies, and political parties can help to create a broader and deeper picture concerning the processes of implementation of organic farming.

6. Conclusions

This article addresses the questions of how local actors are involved in the implementation process of organic farming policies in Costa Rica and how this differs from the integration of other actor types. The paper concentrates on policies that offer alternatives for pesticide use in agriculture and, more concretely, on organic farming, which is a potential way to combine ecological and social protection with economic growth, thus overcoming sustainability trade-offs.

While local actors’ integration is widely accepted and formal rules of actors’ integration are often well-installed at the design stage of land-use policies [20,82,83], the question nevertheless arises as to what extent local actors actually participate in the implementation processes of organic farming policies. My research reveals that in the top-down implementation process of organic farming policies in Costa Rica, mainly national actors play a crucial role, while the integration of local actors is limited. Despite their low integration, results also reveal that local actors try to integrate themselves by creating ties to national actors (see non-reciprocal ties). Therefore, I deduce that local actors are interested in the implementation of organic farming policies, concretely Law No. 8591 and the corresponding Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC, that they want to participate, and they try to realize their aims and put their interests into effect.

Whether local and regional actors play an important role in law and policy-making or if they are widely excluded often depends on the national and subnational contexts [84,85,86]. Scholars’ views vary as to when and how subnational actors are and should be integrated into policy processes [87]. However, there is general agreement that actors belonging to subnational groups can contribute to building a common understanding regarding issues of land-use policies and can therefore optimize task execution [88] and strengthen the connections between actors at different levels [20]. Based on the case selection, I identified no regional actors, but as national actors lie between the local and the global level, they can also act as connectors between those actors and increase efficiency in implementation processes. Indeed, global actors can have a great impact on organic farming due to certification regulations, export provisions, international markets, etc., and they actually received the highest popularity scores in the reputational-power network, emphasizing their importance and the role they are considered to play in this case.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available as they represent the authors’ own field material.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on my master thesis “The implementation of organic farming in Costa Rica: A network analysis about the integration of political actors” submitted in June 2017 at the Institute of Political Science at the University of Bern under the direction of Karin M. Ingold. It was supported by the PESTROP project funded by Eawag, Switzerland. I would like to thank the research group around the PESTROP project for their valuable support during this research and my interview partners, and the people who filled in the questionnaire. I am extremely grateful to Karin M. Ingold for her important support on an earlier draft of this article, and I very much appreciate three anonymous reviewers for comments on an earlier draft. Special thanks also to Majella Horan, Harald Pechlaner and Felix Windegger. All remaining mistakes are, of course, my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of actors mentioned in Law No. 8591 and Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC (own elaboration).

Table A1.

List of actors mentioned in Law No. 8591 and Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC (own elaboration).

| Policy | Name of Actor |

|---|---|

| Law No. 8591 | Ministerio de Comercio Exterior |

| Grupo de personas agricultoras | |

| Programa de Reconversión Productiva del Sector Agropecuario (part of the MAG) | |

| Programa de Fomento de Producción Agropecuaria Sostenible (PEPAS) para el Reconocimiento de los beneficios Ambientales Agropecuarios (part of the MAG) | |

| Programa Nacional de Extensión Agropecuaria (part of the MAG) | |

| Law No. 8591 and Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC | Unidad de Acreditación y Registro en Agricultura Orgánica (ARAO) |

| Comisión Nacional del Consumidor | |

| División de Alimentación y Nutrición del Escolar y del Adolescente | |

| Ministerio de Ambiente y Energía | |

| Promotora de Comercio Exterior de Costa Rica (PROCOMER) | |

| Fondo Especial para el Desarrollo de las micro, pequeñas y medianas empresas FODEMIPYME | |

| Instituto Nacional de Seguros (INS) | |

| Instituto Nacional de Innovación y Transferencia en Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA) | |

| Asociación para el Movimiento de Agricultura Orgánica Costarricense (MAOCO) | |

| Regulation No. 35242-MAG-H-MEIC | Comisión Técnica de Exoneración de Insumos Agropecuarios |

| Programa Integral de Mercadeo Agropecuario-Centro Nacional de Abastecimiento y Distribución de Alimentos | |

| Colegio de Ingenieros Agrónomos | |

| Departamento de Fomento a la Producción Agropecuaria Orgánica (DFPAO) | |

| Dirección Superior de Operaciones Regionales y Extensión Agropecuaria (Now its called Dirección de Extensión Agropecuaria) | |

| Organización Internacional del Trabajo | |

| Oficina Nacional de Semillas | |

| Programa de Abastecimiento Institucional | |

| Programa de Fomento a la Producción Agropecuaria Sostenible | |

| Programa de Investigación y Transferencia de Tecnología Agropecuaria | |

| Sistema Participativo de Garantía | |

| Unidad Técntica Para el Reconocimiento de Incentivos para la Agricultura Orgánica | |

| Programa Nacional de Agricultura Orgánica | |

| Direcciones Regionales del MAG | |

| Instiuto Nacional de Aprendizaje | |

| Universidades | |

| Ministerio de Hacienda | |

| Camara Nacionl de Agricultura y Agroindustria | |

| Cámara de Exportadores de Costa Rica |

Note: This list is different from the list in Appendix A, Table A3 of all identified actors by the reputational, decisional, and reputational approach. This is because the reputational and positional approach added actors, and some actors mentioned in the law and regulation were not established by the time of this analysis or are not part of the actual implementation process.

Table A2.

List of actors participating in debates concerning the design of Law No. 8591 (own elaboration).

Table A2.

List of actors participating in debates concerning the design of Law No. 8591 (own elaboration).

| Name | Name |

|---|---|

| Partido Acción Ciudadana | Comisión de Asuntos Agropecuarios |

| APPTA | Movimiento Libertario |

| Comisión Ambiental | Comisión Permanente de Asuntos Agropecuarios y Recursos Naturales |

| Partido Unión Nacional | Ministerio de Producción |

| Presidente Antonio Pacheco Fernández | pequeñas y medianas empresas |

| Movimiento Libertario | INA |

| Comisión Permanente de Asuntos Agropecuarios y Recursos Naturales | Comisión de Asuntos Internacionales |

| Óscar Méndez | TLC |

| Partido Acción Ciudadana | Fracción del Partido Liberación Nacional |

| Ministro de la Producción, Comisión de Agropecuarios | Diputados, Partido Union Nacional |

| Movimiento de Agricultura Orgánica (MAOCO) | Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza (CATIE) |

| Ministerio de Economía Industria y Comercío | Escuela de Agricultura de la Región de Trópico Húmedo (EARTH) |

| Contraloría General de la República | Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) |

| Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganaderia | Dirección Fitosanitaria |

| Ministerio de Hacienda | Ministerio de Ambiente y Energía |

| Instituto Nacional de Seguros | Corte Suprema de Justicia |

| Bancos Públicos | Banco Popular de Desarrollo Comunal |

| Consejo Nacional de Producción | Instituto de Desarrollo Agrario |

| Universidad de Costa Rica | Universidad Estatal a Distancia |

| Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica | Universidad Nacional |

| Càmara de Agroindustria, Corporación de Fomento Ganadero | Programa de Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo (PNUD) |

| VECO (Agencia Belga de Cooperación) | Certificadora Ecológica |

| Junta Nacional de Ferías del Agricultor, | Pastoral de la Inglesia Católica |

| Consejo Nacional de Consumidores y Usuarios | HIVOS (Agencia Holandesa de Cooperación) |

| FECON | COOPROALDE |

| CEDECO | Certificadora AIMCOPOP |

| Certificadora SKALL | Consejo Nacional de Protección al Consumidor. |

Note: Those protocols of the first and the second debate in the parliament name delegates of different national parties and commissions. One of the reports mentions some private actors as being consulted, but none of them had decision-making power.

Table A3.

List of identified actors by the decisional, positional, and reputational approach (own elaboration).

Table A3.

List of identified actors by the decisional, positional, and reputational approach (own elaboration).

| Acronym | Name |

|---|---|

| APROCO | Asociación de Consumidores y Productores Orgánicos de Costa Rica (Feria Orgánica El Turque) |

| ARAO | Unidad de Acreditación y Registro en Agricultura Orgánica del Servicio Fitosanitario del Estado (Department of Accreditation and Registration on Organic Farming) |

| CactOrg | Comisión Nacional de la Actividad Agropecuaria Orgánica |

| CADEXO | Cámara de Exportadores de Costa Rica (Costa Rican Chamber of Export) |

| Cagag | Camara Nacional de Agricultura y Agroindustria |

| Caproorg | Camara de Productores Orgánicos (Chamber of organic producer) |

| CEDECO | Corporación Educativa para el Desarrollo Costarricense |

| CoopeZarc | Cooperativa de Servicios Múltiples de Zarcero |

| CoTecExo | Comisión Técnica de Exoneración de Insumos Agropecuarios |

| DepFin | Departamento Finaciero del MAG |

| DiExtAgro | Dirección de Extensión Agropecuaria del MAG |

| Ecologica | Certificadora de Productos Orgánicos y Sostenibles |

| FerVerde | Feria Verde de Aranjuez |

| FODEMIPYME | Fondo Especial para el Desarrollo de las micro, pequeñas y medianas empresas (administra Banco Popular y Desarrollo Comunal) |

| FunCoop | Fundecooperación |

| Icafe | ICAFE |

| INA | Instituto Nacional de Aprendizaje |

| INS | Instituto Nacional de Seguros |

| INTA | Instituto Nacional de Innovación y Transferencia en Tecnología Agropecuaria del MAG |

| Jica | Agencia de Cooperación Japonesa |

| Kiwa | Kiwa-BCS |

| MAG | Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganadería (Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock) |

| MagOcci | Dirección Regional Central Occidental del MAG |

| MagZarc | Oficina local del MAG en Zarcero |

| MAOCO | Asociación para el Movimiento de Agricultura Orgánica Costarricense |

| MEIC | Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Comercio (Ministry of Economy, Industry and Technology) |

| MH | Ministerio de Hacienda |

| PNAO | Programa Nacional de Agricultura Orgánica del MAG (The National Organic Agriculture Program) |

| PrimLab | PrimusLabs |

| PROAMO | Red Interactiva de Agricultura Orgánica/Programa de Apoyo a Mercados Orgánicos para Centroamérica y el Caribe |

| PROCOMER | Promotora de Comercio Exterior de Costa Rica |

| RedGene | Red Generativa / Finca Copalchi |

| SNITTA | Fundación para el Fomento y Promoción de la Investigación y Transferencia de Tecnología Agropecuaria, del Sistema Nacional de Investigación y Transferencia de Tecnología Agropecuaria |

| UCR | Universidad de Costa Rica |

| UNED | Universidad Estatal a Distancia |

| Uniper | Agencia Certificadora Control Unión Perú S.A.C. |

| Untecinc | Unidad Técnica para el Reconocimiento de Incentivos para la Agricultura Orgánica del MAG |

| IRET | Instituto Regional de Estudios en Sustancias Tóxicas (Regional Institute for the Study of Toxic Substances) |

References

- UNEP Costa Rica: The ‘Living Eden’ Designing a Template for a Cleaner, Carbon-Free World. Available online: http://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/costa-rica-living-eden-designing-template-cleaner-carbon-free-world (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- The Guardian Costa Rica Unveils Plan to Achieve Zero Emissions by 2050 in Climate Change Fight 2019. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/feb/25/costa-rica-plan-decarbonize-2050-climate-change-fight (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Schmidt, S. Costa Rica’s Environmental Minister Wants to Build a Green Economy. She Just Needs Time. The Washington Post, 31 August 2021. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-solutions/interactive/2021/costa-rica-andrea-meza-climate-change/(accessed on 12 February 2022).

- UNEP Costa Rica Named ‘UN Champion of the Earth’ for Pioneering Role in Fighting Climate Change. Available online: http://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/costa-rica-named-un-champion-earth-pioneering-role-fighting-climate (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Claydon, S. Phasing Out HHPs in Costa Rica; Pesticide Action Network UK: Brighton, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.pan-uk.org/phasing-out-hhps-costa-rica/ (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Alvaro, L. Costa Rica Takes First Place in the World for the Use of Pesticides. Costa Rica Star News, 3 May 2018. Available online: https://news.co.cr/costa-rica-takes-first-place-in-the-world-for-the-use-of-pesticides/72749/(accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Fournier, M.L.; Ramirez, F.; Ruepert, C.; Vargas, S.; Echeverría, S. Diagnóstico Sobre Contaminación de Aguas, Suelos y Productos Hortícolas Por El Uso de Agroquímicos En Lamicrocuenca de Las Quebradas Plantón y Pacayas En Cartago, Costa Rica 2010. Available online: http://www.mag.go.cr/bibliotecavirtual/a00237.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Rodriguez-Rodriguez, C.E.; Matarrita, J.; Herrero-Nogareda, L.; Perez-Rojas, G.; Alpizar-Marin, M.; Chinchilla-Soto, C.; Perez-Villanueva, M.; Vega-Mendez, D.; Masis-Mora, M.; Cedergreen, N.; et al. Environmental Monitoring and Risk Assessment in a Tropical Costa Rican Catchment under the Influence of Melon and Watermelon Crop Pesticides. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 284, 117498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carazo-Rojas, E.; Perez-Rojas, G.; Perez-Villanueva, M.; Chinchilla-Soto, C.; Chin-Pampillo, J.S.; Aguilar-Mora, P.; Alpizar-Marin, M.; Masis-Mora, M.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, C.E.; Vryzas, Z. Pesticide Monitoring and Ecotoxicological Risk Assessment in Surface Water Bodies and Sediments of a Tropical Agro-Ecosystem. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 241, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echeverria-Saenz, S.; Mena, F.; Arias-Andres, M.; Vargas, S.; Ruepert, C.; Van den Brink, P.J.; Castillo, L.E.; Gunnarsson, J.S. In Situ Toxicity and Ecological Risk Assessment of Agro-Pesticide Runoff in the Madre de Dios River in Costa Rica. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 13270–13282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farnham, A.; Fuhrimann, S.; Staudacher, P.; Quirós-Lépiz, M.; Hyland, C.; Winkler, M.S.; Mora, A.M. Long-Term Neurological and Psychological Distress Symptoms among Smallholder Farmers in Costa Rica with a History of Acute Pesticide Poisoning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaver, I.; Chain-Guadarrama, A.; Cleary, K.A.; Sanfiorenzo, A.; Santiago-Garcia, R.J.; Finegan, B.; Hormel, L.; Sibelet, N.; Vierling, L.A.; Bosque-Perez, N.A.; et al. Coupled Social and Ecological Outcomes of Agricultural Intensification in Costa Rica and the Future of Biodiversity Conservation in Tropical Agricultural Regions. Glob. Environ. Chang.-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2015, 32, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO Codex Alimentarius Commission. Organic Agriculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1999; Available online: https://www.fao.org/waicent/faoinfo/food-safety-quality/cd_hygiene/cnt/cnt_sp/sec_3/docs_3.6/Organic%20CXG_032e.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- IBS Soluciones Verdes. Estudio Sobre El Entorno Nacional de La Agricultura Orgánica En Costa Rica, Prepared for Programa Nacional de Agricultur Orgánica, Costa Rica. 2013. Available online: http://www.mag.go.cr/bibliotecavirtual/E70-9267.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- FiBL & IFOAM—Organics International. The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics & Emerging Trends 2021; Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–340. [Google Scholar]

- Willer, H.; Lernoud, J.; Kilcher, L. The World of Organic Agriculture—Statistics and Emerging Trends 2013; FiBL-IFOAM Report; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL), Frick, and International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM): Bonn, Germany, 2013; p. 340. [Google Scholar]

- Galt, R.E. Toward an Integrated Understanding of Pesticide Use Intensity in Costa Rican Vegetable Farming. Hum. Ecol. 2008, 36, 655–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-691-12238-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lubell, M.; Fulton, A. Local Policy Networks and Agricultural Watershed Management. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 673–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ingold, K. How Involved Are They Really? A Comparative Network Analysis of the Institutional Drivers of Local Actor Inclusion. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khailani, D.K.; Perera, R. Mainstreaming Disaster Resilience Attributes in Local Development Plans for the Adaptation to Climate Change Induced Flooding: A Study Based on the Local Plan of Shah Alam City, Malaysia. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolze, M.; Lampkin, N. Policy for Organic Farming: Rationale and Concepts. Food Policy 2009, 34, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockeretz, W. What Explains the Rise of Organic Farming? In Organic Farming. An International History; Cromwell Press: Trowbridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kenis, P.; Schneider, V. Policy Networks and Policy Analysis. Scrutinizing a New Analytical Toolbox. In Policy Networks. Empirical Evidence and Theoretical Considerations; Campus: Frankfurt Germany; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1991; pp. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, K.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Runhaar, H.A.C.; Widmer, A. On the Necessity of Connectivity: Linking Key Characteristics of Environmental Problems with Governance Modes. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 62, 1821–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbrandsen, L.H. Transnational Environmental Governance: The Emergence and Effects of the Certification of Forest and Fisheries; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-1-84980-675-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bodin, Ö.; Prell, C. Social Networks and Natural Resource Management: Uncovering the Social Fabric of Environmental Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-1-139-49657-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, K. Network Structures within Policy Processes: Coalitions, Power, and Brokerage in Swiss Climate Policy. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 435–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykvist, B.; Borgström, S.; Boyd, E. Assessing the Adaptive Capacity of Multi-Level Water Governance: Ecosystem Services under Climate Change in Mälardalen Region, Sweden. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2017, 17, 2359–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Governance of Land Use. Policy Highlights. 2017. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/governance-of-land-use-policy-highlights.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Schweizer, D.; van Kuijk, M.; Ghazoul, J. Perceptions from Non-Governmental Actors on Forest and Landscape Restoration, Challenges and Strategies for Successful Implementation across Asia, Africa and Latin America. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 286, 112251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moschitz, H.; Hrabalova, A.; Stolze, M. Dynamics of Policy Networks. The Case of Organic Farming Policy in the Czech Republic. J. Environ. Pol. Plan. 2016, 18, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.; Weinfurter, A.J.; Xu, K. Aligning Subnational Climate Actions for the New Post-Paris Climate Regime. Clim. Chang. 2017, 142, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ziervogel, G.; Satyal, P.; Basu, R.; Mensah, A.; Singh, C.; Hegga, S.; Abu, T.Z. Vertical Integration for Climate Change Adaptation in the Water Sector: Lessons from Decentralisation in Africa and India. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2019, 19, 2729–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vargas, V.R.; Lawthom, R.; Prowse, A.; Randles, S.; Tzoulas, K. Implications of Vertical Policy Integration for Sustainable Development Implementation in Higher Education Institutions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; Vince, J.; del Río, P. Policy Integration and Multi-Level Governance: Dealing with the Vertical Dimension of Policy Mix Designs. Politics Gov. 2017, 5, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoicka, C.E.; Conroy, J.; Berka, A.L. Reconfiguring Actors and Infrastructure in City Renewable Energy Transitions: A Regional Perspective. Energy Policy 2021, 158, 112544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berka, A.L.; Creamer, E. Taking Stock of the Local Impacts of Community Owned Renewable Energy: A Review and Research Agenda. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 3400–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nabiafjadi, S.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Ahmadvand, M. Social Network Analysis for Identifying Actors Engaged in Water Governance: An Endorheic Basin Case in the Middle East. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 288, 112376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhmouch, A.; Clavreul, D. Towards Inclusive Water Governance: OECD Evidence and Key Principles of Stakeholder Engagement in the Water Sector. In Freshwater Governance for the 21st Century; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 29–49. ISBN 978-3-319-43350-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hegga, S.; Kunamwene, I.; Ziervogel, G. Local Participation in Decentralized Water Governance: Insights from North-Central Namibia. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2020, 20, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriesi, H. Entscheidungsstrukturen Und Entscheidungsprozesse in Der Schweizer Politik; Campus: Frankfurt, Germany, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hooghe, L.; Marks, G. Unraveling the Central State, but How? Types of Multi-Level Governance. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2003, 97, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mazmanian, D.A.; Sabatier, P.A. Implementation and Public Policy; Scott Foresman: Glenview, FL, USA, 1983; ISBN 978-0-673-16561-9. [Google Scholar]

- Van Meter, D.S.; Van Horn, C.E. The Policy Implementation Process: A Conceptual Framework. Adm. Soc. 1975, 6, 445–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, P. The Study of Macro- and Micro-Implementation. Public Policy 1978, 26, 157–184. [Google Scholar]

- Scharpf, Fritz Interorganizational Policy Studies. Issues, Concepts and Perspectives. In Interorganizational Policy Making. Limits to Coordination and Central Control; Sage: London, UK, 1978; pp. 345–370. [Google Scholar]

- Elmore, R.F. Organizational Models of Social Program Implementation. Public Policy 1978, 26, 185–228. [Google Scholar]

- Najam, A. Learning from the Literature on Policy Implementation: A Synthesis Perspective. Available online: http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/4532/ (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Pülzl, H.; Treib, O. Implementing Public Policy. In Handbook of Public Policy Analysis; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-315-09319-2. [Google Scholar]

- Pachoud, C. Territorialization of Public Action and Mountain Pastoral Areas—Case Study of the Territorial Pastoral Plans of the Rhône-Alpes Region, France. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, K.; Balsiger, J.; Hirschi, C. Climate Change in Mountain Regions: How Local Communities Adapt to Extreme Events. Local Environ. 2010, 15, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, C. Strengthening Regional Cohesion: Collaborative Networks and Sustainable Development in Swiss Rural Areas. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Back to the Future: Ecosystem Dynamics and Local Knowledge. In Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 121–146. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. A Conceptual Framework for Analysing Adaptive Capacity and Multi-Level Learning Processes in Resource Governance Regimes. Glob. Environ. Chang.-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2009, 19, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S. Public-Private Partnerships: Theory and Practice in International Perspective; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, B.; Taylor, K. Vulnerability and Adaptation to Climate Change: A Review of Local Actions and National Policy Response. Clim. Dev. 2012, 4, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]