Abstract

Greenwashing has become a widespread phenomenon and obstructs green products, but literature on how consumers react to misbehaving brands is still scarce. This study aims to investigate the effect of greenwashing on consumers’ brand avoidance, integrating the mediating effect of brand hypocrisy and the moderating effect of CSR–CA belief. Data were acquired from a questionnaire survey of 317 consumers. Hypotheses were tested in a first-stage moderated mediation model with a bootstrapping method using the PROCESS program in SPSS. The empirical results demonstrated that greenwashing has a positive effect on brand avoidance, which is partially mediated by brand hypocrisy. Meanwhile, the positive effects of greenwashing on brand hypocrisy and brand avoidance are both weaker at higher levels of CSR–CA belief. Furthermore, the mediating effect of brand hypocrisy is also weaker at higher levels of CSR–CA belief. Based on these findings, we recommend that brands fulfill their environmental claims and balance their quality control, manufacturing costs and environment protection. Moreover, the government and environmental protection organizations should educate the public that there is not necessarily a tradeoff between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate capability (CA).

1. Introduction

Brands are the major source of product differentiation, and firms are eager to promote their brands by all means [1]. As consumers become more concerned about environmental issues, more and more brands advertise the environmental features of their products nowadays [2,3]. However, not all brands fully accomplish their claims because some of them lack enough capabilities or resources to undertake the environmental strategy or are just unwilling to bear the additional costs [4]. This phenomenon has been recognized as greenwashing, which can be defined as “tactics that mislead consumers regarding the environmental practices of a company or the environmental benefits of a product or service” [5] (pp. 15–16). It has been widely criticized and become a severe social problem. Not only do environmental activists denounce greenwashing as simply public relations campaigning, but consumers also now possess a more sophisticated understanding of this trick [2,6]. However, even though the topic of greenwashing has attracted increasing academic interest in the past decade, the literature remains scarce and is limited to skepticism about all green products instead of brand-related reactions [4,6,7]. Too much emphasis on the effect on the whole green marketing movement alleviates the worries of those who are trying to greenwash. Only when managers realize that greenwashing damages their own brands will they reject greenwashing spontaneously. To address this issue, this study aims to investigate the effect of greenwashing on consumers’ brand avoidance.

Brand avoidance is “the conscious, deliberate, and active rejection of a brand that the consumer can afford, owing to the negative meaning associated with that brand” [8] (p. 330). It mainly refers to the deliberate and conscious act of refraining from using and purchasing a particular brand, even though it is available, accessible and financially affordable [9]. Most previous research has focused on the positive aspects associated with brands, such as brand attachment [10], brand trust [11], brand love [12], brand commitment [13], and brand loyalty [14]. However, the negative aspects, such as brand hate [15], brand avoidance [16], and brand forgiveness [17], are relatively underexplored. Even though some negative aspects are covert and less noticeable, they may do great harm to the brand’s reputation and profitability. It is rewarding to be one of the preferred brands, but it is also vital to not be among the avoided ones [18], let alone that negative word-of-mouth is more sustainable and influential for potential consumers [19,20]. Consumers avoid a particular brand because of various reasons, such as dissatisfactory experience, moral wrong doing or personal identity conflicts [19]. Greenwashing represents overstating the environmental features of the brand, which will disappoint the consumers when it is found out [4]. Cheating is also immoral and damages the brand’s image, which ruins consumers’ trust and loyalty eventually [2,5]. Moreover, consumers who choose green products are usually committed to environmental protection. When they realize that the brand is not actually protecting the environment, they will be angry and despise the greenwashed brand [6]. In this sense, it is interesting to investigate whether greenwashing will result in brand avoidance.

To examine how greenwashing results in brand avoidance, this study has also considered the mediating effect of brand hypocrisy. Brand hypocrisy refers to “a brand perceived as intentionally projecting false or unrealistic appearances, thereby implying the dissimulation or manipulation of attributes, motivations or beliefs” [21] (p. 599). Consumers readily criticize brands for misbehaving, lacking transparency, or acting in a manner contrary to their beliefs nowadays [21]. Hypocrisy occurs when there is a disconnection between what a brand claims and what a brand does. In the case of greenwashing, brands are cheating regarding their claims about the environmental features of their products, which can be considered being dishonest [19], insincere [22], and inauthentic [23]. This is especially true because consumers have broader access to information about what a brand truly does with the prevalence of social media nowadays [6,24]. Notably, previous literature found that brand hypocrisy ruins the brand’s reputation and consumers’ trust [25,26]. Then, brand hypocrisy may further result in brand avoidance because no one likes to be fooled. Therefore, the influence of greenwashing on brand avoidance may take effect through the mediating role of brand hypocrisy.

Furthermore, many previous studies suggest that corporate social responsibility (CSR) does not always lead to actual consumption [27]. Many consumers claim their preference for CSR but seldomly take it into account when it comes to real consumption. It is true that individuals vary in CSR orientation and react differently to brands’ CSR initiatives [28]. Some consumers even believe that there is a trade-off between CSR and corporate capabilities (CA) [29]. This belief is called CSR–CA belief, which is defined as the “general beliefs about the trade-offs companies make in supporting CSR initiatives” [30] (p. 225). Not all consumers are committed to protecting the environment and gain intrinsic joy from it; some may even see such activities as a needless expense [31]. They tend to complain that consumers pay the price, while brands take the credit [32,33]. Likewise, even though most consumers criticize greenwashing, they may have different tolerance levels for it [34]. Those who have a strong belief that there is a tradeoff between CSR and CA may forgive or even indulge greenwashing, especially when the greenwashed brand has lower prices [31]. Therefore, this study has also considered the moderating effect of CSR–CA belief to clarify the boundary conditions of the effects of greenwashing.

To sum up, this study has constructed a moderated mediation model to investigate the effect of greenwashing on consumers’ brand avoidance, integrating the mediating effect of brand hypocrisy and the moderating effect of CSR–CA belief. By revealing how and when greenwashing results in brand avoidance, this study hopes to extend the theories on greenwashing and persuade brands to truly fulfill their environmental claims.

2. Theories and Hypotheses

2.1. Greenwashing and Brand Avoidance

Even though greenwashing has received increasing academic attention recently, there are still debates about what it is [3,35]. Scholars have summarized seven sins of greenwashing, which include the sins of hidden trade-offs, no proof, vagueness, worshiping false labels, irrelevance, lesser of two evils, and fibbing [36]. These seven sins help to capture what specific behaviors can be viewed as greenwashing and are accepted widely. Many scholars consider greenwashing as dealing with environmental issues, but some other scholars argue that it should also include social issues [35]. In reality, environmental responsibilities are part of social responsibilities, and many companies also exaggerate their other kinds of social responsibilities. Therefore, we advocate that greenwashing mainly addresses environmental issues, but also considers social issues. Some studies have focused only on false advertisements that mislead consumers on purpose [37], while more studies have expanded to include claims without proof and selective disclosure of positive information [4,6]. Even though these actions differ in the degree of falsehood in the message, they all create a better image for the brands than they deserve. Therefore, we advocate that greenwashing include different kinds of behaviors, such as false advertisements, claims without proof, and selective disclosure of positive information.

The concept of brand avoidance should also be clarified. Brand avoidance is not the antithesis of brand loyalty, nor the synonym of brand switching or boycotting [16]. Consumers who are not loyal to a brand do not necessarily reject the brand deliberately [19]. In comparison, brand switching may simply be a result of unaffordability, unavailability or inaccessibility, so consumers are left with no choice [38,39], while brand avoidance particularly emphasizes that consumers reject the brand when they have the ability to purchase from it as well as access to the brand [9]. Although boycotting is also a kind of anti-consumption and resistance, it is usually a punitive ban at a social/group level, whereas brand avoidance is individually based [16]. Therefore, brand avoidance is a relatively new concept with its unique connotation and worth further examination. Another issue includes the subdimensions of brand avoidance. Some scholars have identified several kinds of brand avoidance based on the reasons why consumers avoid the brand, such as experience avoidance, moral avoidance, identity avoidance, and deficit-value avoidance [16,19]. However, the antecedents should not be confused with the subdimensions. In this study, we advocate that brand avoidance is a unidimensional construct, which can result from one or several of these reasons.

Consumers are interested in eco-friendly brands because they are not only concerned about the environment, but also expect personal benefits from green products [4,6]. If a brand overstates the environmental functionality of its products, consumers are reasonable to doubt whether they will benefit from the so called “green products”, let alone the extra cost [5]. This disappointing experience will even trigger hatred for the brand and result in avoidance [16]. Meanwhile, according to institutional theory, brands should appear legitimate to various audiences to obtain their support [40]. This may be one of the reasons why brands wish to be viewed as green brands. However, they will be worse off when they are found to be cheating through false advertisements or selective disclosure. It is true that undertaking CSR satisfies consumers, but it is even more true that consumers hate to be fooled. The scandal of greenwashing will damage the brand’s reputation and legitimacy, even after they have repented. In addition, according to social identity theory, people strive to maintain a positive social identity by differentiating their in-groups and out-groups [41]. They stick to certain beliefs and behaviors that define the group and avoid being recognized as other groups. In consumption, consumers demonstrate their self-concept through what they consume and what they refuse to consume [42]. If a brand is recognized to be greenwashed, consumers may never purchase its products because they do not want to be identified with brands that do not protect the environment. Finally, many consumers may choose to avoid greenwashed brands because they wish to punish the brands and remind them of their responsibilities and obligations [43]. Therefore, we argue that greenwashing will result in consumers’ brand avoidance and propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Greenwashing will be positively associated with brand avoidance.

2.2. The Mediating Effect of Brand Hypocrisy

Brand hypocrisy is a perception in consumers’ minds that a brand claims to be something it is not, especially regarding corporate social responsibilities [44]. For example, a brand is perceived as hypocritical when it fails to deliver on promises, fails to acknowledge negative impacts on consumers or society, or purposely promotes unrealistic images [21]. By engaging in these behaviors, the brand is likely to benefit from a perfect image that it does not deserve. However, these behaviors also raise a negative association in consumers’ minds, which grows into a brand personality over time [21]. Some studies further argued that hypocrisy could be conceptualized as a multifaceted concept, which includes moral hypocrisy, behavioral hypocrisy and hypocrisy attribution [45]. However, this notion has not gained popularity yet and most studies treat brand hypocrisy as moral hypocrisy or behavioral hypocrisy or a combination of the two. At any rate, previous studies have demonstrated that brand hypocrisy negatively influences brand reputation [46] and brand trust [25] and positively influences consumer skepticism [26] and brand-switching intention [25].

CSR activities improves a brand’s image only when consumers believe the activities are true and the result of a sincere motive [46]. Greenwashing represents that there is a mismatch between the environmental claims and the brands’ practices, which may raise suspicions and confusion among consumers [6,47]. When a brand claims to be environmentally responsible but does not engage in any specific activities to protect the environment, it is likely to be viewed as hypocritical because it does not act as it says [25]. It is also reasonable to doubt the authenticity of a brand when it is found to selectively disclose positive information without fully disclosing negative information [48]. Consumers are apt to believe that the brand will do anything to maximize its own benefit even if it damages consumers’ benefits. Because of the dishonest history, consumers will find it difficult to believe its statements in the future [25]. Even if the brand does not intend to cheat but just lacks solid evidence to support its claims, consumers will also be skeptical and hesitate to trust the brand’s statements, especially when they have seen more and more greenwashed brands recently [4,26]. Therefore, we argue that greenwashing positively influences brand hypocrisy and propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Greenwashing will be positively associated with brand hypocrisy.

Perception of hypocrisy is often related to trust, which is critical to the relationship between consumers and brands [29]. When consumers perceive a brand as hypocritical, they will be confused and doubt whether its claims are trustworthy [24]. Then, they will hesitate to choose its products because they are not sure whether such products will meet their expectations. They will have trouble trusting the brand’s products and perceive high risks in purchasing them [49]. The worries may even spread beyond environmental claims to functional claims [24,44]. Even if the brand actually fulfill its environmental responsibility later, the stereotype of hypocrisy also leads consumers to question the motives underlying these CSR actions and diminishes the positive effect of CSR [26]. What’s worse, brand hypocrisy also generates a sense of betrayal [25]. The enraged consumers will then reject the brand and even spread negative word-of-mouth to punish it [43,50]. Even for those who have never purchased the brand before, perceptions of hypocrisy generated from negative word-of-mouth or news reports also drive them away from trying the brand [8,51]. Therefore, we argue that brand hypocrisy positively influences brand avoidance and propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

Brand hypocrisy will be positively associated with brand avoidance.

Considering that greenwashing positively influences brand hypocrisy and brand hypocrisy positively influences brand avoidance, we further argue that there will be a mediating effect of brand hypocrisy in the relationship between greenwashing and brand avoidance and propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2c (H2c).

Brand hypocrisy mediates the relationship between greenwashing and brand avoidance.

2.3. The Moderating Effect of CSR–CA Belief

Even though CSR has dominated business practices and public awareness, individuals still vary in CSR orientation and have different beliefs in organizations’ CSR initiatives [28]. The CSR–CA belief is also known as the CSR–CA tradeoff [29,30]. CSR refers to the brand’s commitment and activities it takes to promote social or environmental welfare, and CA refers to its professional capability to provide quality products/services [29]. It is found that CSR and CA interact to positively affect consumers’ evaluations of product quality and the brand [52]. Consumers usually love brands that willingly undertake CSR and also demonstrate strong CA, but such brands are quite rare. Although many consumers believe that CSR pushes brands to develop better technologies and adopt higher product standards, some other consumers believe that investing too many resources in CSR drains the resources that could have been devoted to developing technologies that really help to provide quality products [27,31]. Some of them even see CSR activities as a needless expense instead of a benefit and believe green products are of lower quality standards [53,54]. They believe that all corporations’ resources are limited and that there is always a tradeoff between CSR and CA. This belief may affect their response to corporations’ CSR activities.

When consumers believe CSR initiatives are fulfilled at the expense of CA, they evaluate its CSR efforts less positively [34]. From another perspective, these consumers may also be more tolerant to those who did not undertake CSR. Consumers who hold a strong belief about the CSR–CA tradeoff view that the additional costs and higher prices associated with green products are paid by consumers but provide few benefits [30,31]. They tend to complain that consumers pay the price while brands take the credit for being socially responsible [32,33]. What’s worse, these consumers even believe that socially responsible behavior drains company resources and lowers product standards [31]. In this sense, CSR may even harm consumer satisfaction if the brand emphasizes CSR activities too much without practical innovation and quality improvement [55]. These thoughts undermine the value of CSR activities and provide excuses for greenwashing. They may view greenwashing as a solution to satisfy the public expectation of environmental protection without increasing the burden of consumers. Instead of accusing the greenwashed brand of hypocrisy, they may even praise the brand for being flexible. Even if the greenwashed products do not perform well environmentally, they do not really care about it. Instead, they argue that socially responsible behavior often covers up inferior products because people seldomly criticize the “responsible” brands [31]. In contrast, those who believe there is no tradeoff between CSR and CA are more likely to attribute greenwashing to the brand’s immorality and incompetence and reject the brand [2,6]. They may argue that CSR and CA are synergistic and that a brand should be both socially responsible and provide products of high quality. In this case, they will be less likely to indulge greenwashed brands and reject purchasing their products. Therefore, we argue that belief about the tradeoff between CSR and CA alleviates the positive effects of greenwashing on brand hypocrisy and brand avoidance and propose the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 3a (H3a).

CSR–CA belief negatively moderates the relationship between greenwashing and brand avoidance, such that the positive effect of greenwashing on brand avoidance will be weaker at higher levels of CSR–CA belief.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b).

CSR–CA belief moderates the relationship between greenwashing and brand hypocrisy, such that the positive effect of greenwashing on brand hypocrisy will be weaker at higher levels of CSR–CA belief.

Hypothesis 3c (H3c).

CSR-belief moderates the mediating effect of brand hypocrisy in the relationship between greenwashing and brand avoidance, such that the mediating effect will be weaker at higher levels of CSR–CA belief.

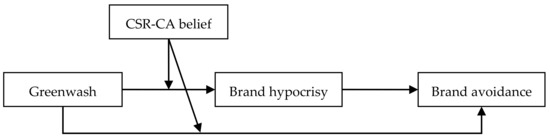

The research framework and hypotheses are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework and hypotheses.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

Data were acquired from a questionnaire survey conducted in Hangzhou, China. To obtain access to various samples, ordinary consumers who were wandering in shopping malls were invited to join the survey. The consumers were free to refuse to participate or quit at any time if they found the questions not suitable to answer. A little souvenir worth about CNY 10 was offered to those who completed the survey. An oral explanation was given to inform the participants of the purpose of the study. It was also promised that the survey was anonymous and that the result would only be used for academic purposes. At the very beginning of the questionnaire, the participants were asked to name one brand that they are familiar with and answer the questions accordingly.

A total of 380 questionnaires were distributed, resulting in 317 completed and valid samples, yielding a response rate of 83.4%. Of the participants, 138 (43.5%) were male, and 179 (56.5%) were female. As for age, 61 (19.2%) were aged 20 or younger, 110 (34.7%) were aged between 21 and 25, 97 (30.6%) were aged between 26 and 30, and 49 (15.5%) were aged 31 or older. As for education, 113 (35.6%) had a college degree or lower level of education, 106 (33.4%) had a bachelor’s degree, 87 (27.4%) had a master’s degree, and 11 (3.5%) had a doctorate. As for household income, 62 (19.6%) had an annual household income of less than CNY 100,000, 112 (35.3%) between CNY 100,001 and CNY 200,000, 110 (34.7%) between CNY 200,001 and CNY 500,000, and 33 (10.4%) over CNY 500,000. As for the brands, 164 (51.7%) chose an electronic brand and 153 (48.3%) chose a fashion brand. In addition, 140 (44.2%) chose a Chinese brand and 177 (55.8%) chose an international brand.

3.2. Measures

All the variables were measured with mature scales developed and validated by previous studies. As the survey was carried out in China, the items were translated from English into Chinese through the back-translation process until no discrepancy between the original items and the translations existed. All the scales were measured with a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree.

Greenwashing. We measured greenwashing with the five-item scale from Xiao et al. [6], which was originated by Chen and Chang [49]. One sample item is “The products of this brand mislead with words in their environmental features.” The Cronbach’s α was 0.87 in this study.

CSR–CA belief. We measured CSR–CA belief with the eight-item scale from Pritchard and Wilson [31], which was originated by Sen and Bhattacharya [30]. One sample item is “Socially responsible behavior weakens a company’s ability to provide the best.” The Cronbach’s α was 0.89 in this study.

Brand hypocrisy. We measured brand hypocrisy with the three-item scale developed by Wagner et al. [44]. One sample item is “What this brand says and does are two different things.” The Cronbach’s α was 0.86 in this study.

Brand avoidance. Brand avoidance is a relatively new construct without any generally accepted scales. Shin et al. used a three-item scale to measure whether consumers will stay away from a certain brand [56]. Khan et al. used another three-item scale to measure consumers’ intentions to stop purchasing a certain brand [18]. Both of the two scales capture important features of brand avoidance and were integrated into a six-item scale. To fit the research context of this study, the wording of the items was slightly modified. One sample item is “I will avoid visiting the stores of this brand.” The Cronbach’s α was 0.90 in this study.

Control variables. Along with the previous research on greenwashing and brand avoidance [6,18], gender, age, education, household income, brand industry and brand nationality were included as control variables. Apart from these demographic variables, brand familiarity was also chosen as a control variable, as it might affect how consumers perceive and react to a specific brand and how accurate their judgements are [57]. Brand familiarity was measured with the three-item scale developed by Siew et al. [57], which was originated by Kent and Allen [58]. One sample item is “I am familiar with this brand.” The Cronbach’s α was 0.82 in this study.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Validation

First, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to assess the validity issues. The results of model comparison showed that the five-factor model has the best fit with the data, as presented in Table 1. The standardized regression weight (SRW), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) of the five-factor model are presented in Table 2. All the SRWs were larger than or close to 0.7, all the CRs were larger than 0.8 and all the AVEs were larger than 0.5. In addition, as presented in Table 3, the square roots of AVE of all variables were larger than the corresponding inter-construct correlations. Thus, the construct validities and discriminant validities were acceptable. Second, as reported previously, all the Cronbach’s α values were larger than 0.8, which indicates that the internal reliabilities were also acceptable. Third, to assess the problem of common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted in the exploratory factor analysis with all items. Five factors were extracted, with 67.857% variance explained in total. The amount of variance explained by the first factor was 31.120%, which is smaller than the critical criterion of 40% and indicates that the common method bias was not severe.

Table 1.

Model comparison of confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 2.

Items, standardized regression weight, composite reliability and average variance extracted.

Table 3.

Means, S.D.s, correlations and square roots of AVE.

4.2. Descriptive Analysis

The means, standard deviations (S.D.s), correlations and the square roots of AVE are presented in Table 3. Greenwashing was positively correlated with brand hypocrisy (r = 0.450, p < 0.01) and positively correlated with brand avoidance (r = 0.490, p < 0.01). Meanwhile, brand hypocrisy was also positively correlated with brand avoidance (r = 0.649, p < 0.01). These results were consistent with and provided initial support to the hypotheses.

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

The hypotheses were tested in a first-stage moderated mediation model with a bootstrapping method using the PROCESS V4.0 developed by Hayes in the SPSS. Specifically, the “Model 4” from the template of PROCESS was used to test the direct effect of greenwashing on brand avoidance and the mediating effect of brand hypocrisy, and the “Model 8” from the template of PROCESS was used to test the moderating effects of CSR–CA belief. We chose a 95% confidence level for bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals with 5000 bootstrapping samples. The results are summarized in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 4.

Results of the regression analysis.

Table 5.

The mediating effect of brand hypocrisy.

Table 6.

The moderated mediating effect of CSR–CA belief.

As presented in Table 4, the results of Model 1 showed that greenwashing was positively and significantly associated with brand avoidance (β = 0.4203, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported. Meanwhile, the results of Model 4 showed that greenwashing was positively and significantly associated with brand hypocrisy (β = 0.3800, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 2a was supported. In addition, the results of Model 2 showed that brand hypocrisy was also positively associated with brand avoidance (β = 0.5365, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 2b was also supported. Moreover, as presented in Table 5, the index of the mediating effect of brand hypocrisy in the relationship between greenwashing and brand avoidance was 0.2039, and the 95% confidence interval was [0.1443, 0.2739], which did not include zero. Therefore, the mediating effect of brand hypocrisy was significantly positive. Thus, Hypothesis 2c was also supported. Considering that the direct effect of greenwashing on brand avoidance is still significantly positive (index = 0.2164, 95% confidence interval = [0.1278, 0.3049], which did not include zero), it can be concluded that brand hypocrisy partially mediates the effect of greenwashing on brand avoidance.

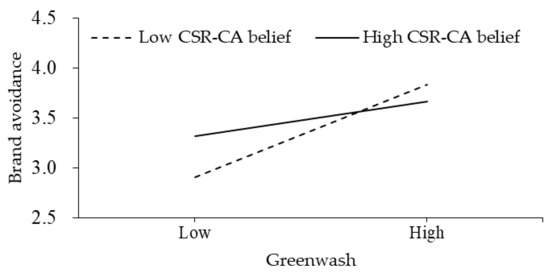

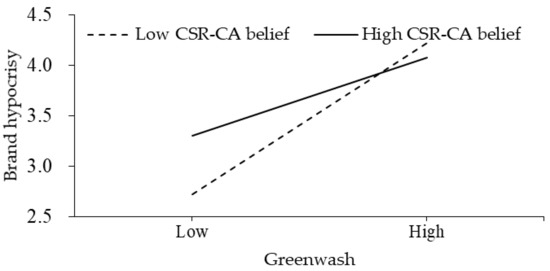

Furthermore, the results of Model 3 showed that the interaction of greenwashing and CSR–CA belief was significantly and negatively associated with brand avoidance (β = −0.1057, p < 0.01). Thus, Hypothesis 3a was supported. The results of Model 5 showed that the interaction of greenwashing and CSR–CA belief was significantly and negatively associated with brand hypocrisy (β = −0.1229, p < 0.01). Thus, Hypothesis 3b was also supported. To illuminate the moderating effects of CSR–CA belief, the samples were separated into two groups (mean + S.D., mean − S.D.) for further regression analysis. As shown in Figure 2, the positive effect of greenwashing on brand avoidance was weaker for the high-CSR–CA-belief group. Therefore, CSR–CA belief negatively moderates the relationship between greenwashing and brand avoidance, which provides further evidence for Hypothesis 3a. As shown in Figure 3, the positive effect of greenwashing on brand hypocrisy was also weaker for the high-CSR–CA-belief group. Therefore, CSR–CA belief also negatively moderates the relationship between greenwashing and brand hypocrisy, which provides further evidence for Hypothesis 3b.

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of CSR–CA belief in the relationship between greenwashing and brand avoidance.

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of CSR–CA belief in the relationship between greenwashing and brand hypocrisy.

To test the moderated mediation effect, the conditional indirect effects of greenwashing on brand avoidance via brand hypocrisy at levels of CSR–CA belief were computed and presented in Table 6. The standardized regression coefficient of the mediating effect of brand hypocrisy was 0.2607 at the lower level of CSR–CA belief, decreased to 0.1976 at the medium level of CSR–CA belief and decreased to 0.1345 at the higher level of CSR–CA belief. The index of the difference was −0.0631, and the 95% confidence interval was [−0.1119, −0.0178], which did not include zero. Therefore, the positive mediating effect of brand hypocrisy was significantly weaker at higher levels of CSR–CA belief. Thus, Hypothesis 3c was supported.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study aims to investigate the effect of greenwashing on consumers’ brand avoidance and reveal the mechanism by examining the mediating effect of brand hypocrisy and the moderating effect of CSR–CA belief. Seven hypotheses were put forward, and all of them were supported. First, Hypothesis 1 was supported, which indicated that greenwashing leads consumers to avoid the brand deliberately. Second, Hypotheses 2a, 2b and 2c were all supported, which indicated that greenwashing also results in consumers’ perception of brand hypocrisy, and brand hypocrisy results in brand avoidance; thus, there is an indirect effect of greenwashing on brand avoidance via brand hypocrisy. Third, Hypotheses 3a, 3b, and 3c were all supported, which indicated that the effects of greenwashing on brand hypocrisy and brand avoidance, as well as the mediation effect of brand hypocrisy, were all weaker at higher levels of CSR–CA belief. In summary, the positive effect of greenwashing on brand avoidance, which is partially mediated by brand hypocrisy, was found and confirmed, while it was found that consumers who believe in the tradeoff between CSR and CA will be influenced by greenwashing less significantly.

Based on these findings, this study is able to make several contributions to the theories. First, most previous studies on greenwashing have focused on skepticism about all green products [2,4,7], while this study was devoted to investigating consumers’ brand-related reactions. This is meaningful because it helps to remind brands that greenwashing not only obstructs the prevalence of green products, but also damages their own economic performances. Only when detrimental consequences are inflicted on the misbehaved brands will they realize that there is no benefit in greenwashing. Second, different from the previous studies that focused on the positive aspects associated with brands [6,11,13], this study tried to explain why consumers hate and reject a greenwashed brand deliberately. This is of great theoretical importance because some brands may not pursue being reputable, but no brand can stand to be hated and avoided [38]. It provides a new perspective to understand the effect of greenwashing and introduce many possible research directions. For instance, by investigating the theories of brand forgiveness, we may be able to determine how a greenwashed brand can retrieve consumers’ trust [17]. Third, by examining the mediating effect of brand hypocrisy, this study has integrated the theories of greenwashing, brand hypocrisy and brand avoidance to reveal the mechanism of how greenwashing results in brand avoidance [5,8,21]. Meanwhile, the partially mediating effect also indicates that there may be other mediators in the relationship between greenwashing and brand avoidance. Fourth, this study has taken individual differences into consideration and demonstrated the moderating effect of CSR–CA belief, which is original in the field of greenwashing [3,31]. This is inspiring because it not only helps to clarify the theoretical boundary of the effect of greenwashing, but also deepens our understanding of consumers’ beliefs about CSR and the associated influences.

5.2. Practical Implications

Several implications could be derived from the findings, for brands and society as well. First, since greenwashing damages brands’ reputations and economic performances, brands should fully accomplish their environmental responsibilities, for their own good. They should avoid using vague expressions to mislead consumers, provide convincing evidence for their genuine green initiatives and never deliver false environmental messages to consumers. In addition, exaggerating environmental claims is noxious and may be worse than not taking on the responsibilities. Therefore, brands should genuinely adopt environmental responsibilities within their reach instead of claiming objectives that are unrealistic. Second, because consumers of stronger CSR–CA belief are less likely to avoid the greenwashed brands, it is necessary to educate the public that undertaking environmental responsibilities does not necessarily damage corporate capabilities. The government and environmental protection organizations should select some outstanding brands that have performed well in both protecting the environment and providing quality products and propagandize their practices and achievements. In advertising the green products, brands should not just emphasize the green features of their products, but also convince consumers that the green features improve instead of lower their quality standards. Third, as consumers are becoming more sophisticated and have broader access to information, it is also necessary to change the traditional trick that promotes green products at an abnormally high price to avoid leading consumers to feel that buying environmentally friendly products is unfair. Brands should make it a competitive strategy to balance their quality control, manufacturing costs and environment protection.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

There are also several limitations in this study. First, the cross-sectional design limited this study to unequivocally determine the direction of causality. Even though we have hypothesized that greenwashing results in brand hypocrisy and brand avoidance based on rigorous theoretical deduction, we cannot exclude the possibility of reversed relationship with the current design. Hence, an experimental design or a longitudinal design would have been preferred. Second, the data were acquired from a single group of participants at the same time and may suffer from common method bias. Even though the Harman’s single-factor test supported that the problem was not severe, measuring some of the variables with data from other sources would have been preferred. For instance, the measurement of greenwashing could be substituted by brands’ actual greenwashing behavior, with objective records or evaluations by a third party. Third, the sample size was relatively small, which limits the robustness of the results. In addition, the survey was only conducted in Hangzhou, China, resulting in the concern that the findings may not be generalizable in the West, or other areas of China. In addition to the cultural context, the prevalence of CSR–CA belief may be quite different between China and the West. This may not only influence what kind of behavior is viewed as greenwashing, but also affect how consumers react to it. Further studies can be conducted to compare the differences in different countries and cultures to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Last finally, as this study has discussed, greenwashing contains several kinds of behaviors, which are the result of different intentions and of different degrees of falsehood in the messages. It will be very insightful to identify the subdimensions of greenwashing and investigate their different effects on consumer responses in the future.

6. Conclusions

In summary, this study has demonstrated that greenwashing results in consumers’ brand avoidance and that the effect is partially mediated by brand hypocrisy. By revealing the detrimental outcomes of greenwashing, this study highlights that undertaking environmental responsibilities is not only a moral requirement for brands, but also a vital determinant of their economic success. This may help to strengthen the intrinsic motive of brands to fulfill their environmental claims spontaneously. In addition, this study has also demonstrated that the detrimental effects of greenwashing are alleviated by CSR–CA belief. Therefore, it is necessary to educate the public that there is not necessarily a tradeoff between CSR and CA, and brands should strive to balance their quality control, manufacturing costs and environment protection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.X. and Y.W.; methodology, Z.X. and D.G.; formal analysis, Z.X.; investigation, Z.X. and Y.W.; resources, Z.X. and D.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.X. and Y.W.; writing—review and editing, Z.X. and D.G.; supervision, D.G.; project administration, Z.X. and D.G.; funding acquisition, Z.X. and D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (22NDJC014Z), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LQ22G020006), National Natural Science Foundation of China (72101233), National Social Science Foundation of China (21BJY087), and Research Projects of the Department of Education of Zhejiang Province (Y202045242).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for the research, since the questionnaire survey did not involve ethical issues and was conducted in accordance with general ethical guidelines and legal requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. We informed the participants that they could choose to participate or not and that they could quit at any time if they found the questions not suitable to answer. An oral explanation was given to inform the participants of the purpose of the study. It was also promised that the survey was anonymous and that the result would only be used for academic purposes.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Davcik, N.S.; Sharma, P. Impact of product differentiation, marketing investments and brand equity on pricing strategies: A brand level investigation. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 760–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, A.; Wang, T.; Chen, Y. Greenwash and green purchase behaviour: The mediation of green brand image and green brand loyalty. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2020, 31, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemes, N.; Scanlan, S.J.; Smith, P.; Smith, T.; Aronczyk, M.; Hill, S.; Lewis, S.L.; Montgomery, A.W.; Tubiello, F.N.; Stabinsky, D. An integrated framework to assess greenwashing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Yang, Z.; Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W.; Cao, T.K. Greenwash and green purchase intention: The mediating role of green skepticism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parguel, B.; Benoît-Moreau, F.; Larceneux, F. How sustainability ratings might deter ‘greenwashing’: A closer look at ethical corporate communication. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ji, X.; Cai, L. Greenwash, moral decoupling, and brand loyalty. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2021, 49, 10038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.M.M.R.; Yifei, L.; Bhutto, M.Y.; Ali, R.; Alam, F. The influence of consumption values on green purchase intention: A moderated mediation of greenwash perceptions and green trust. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2019, 13, 826–848. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A.; Lee, M.S. Prepurchase determinants of brand avoidance: The moderating role of country-of-origin familiarity. J. Glob. Mark. 2014, 27, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knittel, Z.; Beurer, K.; Berndt, A. Brand avoidance among Generation Y consumers. Qual. Mark. Res. 2016, 19, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japutra, A.; Ekinci, Y.; Simkin, L. Self-congruence, brand attachment and compulsive buying. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Portal, S.; Abratt, R.; Bendixen, M. The role of brand authenticity in developing brand trust. J. Strateg. Mark. 2019, 27, 714–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Bairrada, C.; Peres, F. Brand communities’ relational outcomes, through brand love. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G.; Agarwal, J.; Malhotra, N.K.; Varshneya, G. Does brand experience translate into brand commitment?: A mediated-moderation model of brand passion and perceived brand ethicality. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamitov, M.; Wang, X.; Thomson, M. How well do consumer-brand relationships drive customer brand loyalty? General-izations from a meta-analysis of brand relationship elasticities. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 46, 435–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetscherin, M. The five types of brand hate: How they affect consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoom, R.; Kosiba, J.P.; Djamgbah, C.T.; Narh, L. Brand avoidance: Underlying protocols and a practical scale. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetscherin, M.; Sampedro, A. Brand forgiveness. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 633–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ashraf, R.; Malik, A. Do identity-based perceptions lead to brand avoidance? A cross-national investigation. Asia Pac. J. Market. Logist. 2019, 31, 1095–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Motion, J.; Conroy, D. Anti-consumption and brand avoidance. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Mitra, S.; Zhang, H. Research note—When do consumers value positive vs. negative reviews? An empirical inves-tigation of confirmation bias in online word of mouth. Inform. Syst. Res. 2016, 27, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guèvremont, A. Brand hypocrisy from a consumer perspective: Scale development and validation. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 598–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehle, N.; Otnes, C.; Supphellen, M. Consumers’ perceptions of the dimensions of brand personality. J. Consum. Behav. 2011, 10, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.J.; Arsel, Z. The Starbucks brandscape and consumers’ (anticorporate) experiences of glocalization. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hur, W.; Yeo, J. Corporate brand trust as a mediator in the relationship between consumer perception of CSR, corporate hypocrisy, and corporate reputation. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3683–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Bhaduri, G.; Ha-Brookshire, J.E. What to say and what to do: The determinants of corporate hypocrisy and its nega-tive consequences for the customer–brand relationship. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 30, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; van Esch, P.; Northey, G.; Lee, M.S.W.; Dimitriu, R. Hypocrisy, skepticism, and reputation: The mediating role of corporate social responsibility. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 706–720. [Google Scholar]

- Öberseder, M.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Gruber, V. “Why don’t consumers care about CSR?”: A qualitative study exploring the role of CSR in consumption decisions. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singhapakdi, A.; Lee, D.; Sirgy, M.J.; Senasu, K. The impact of incongruity between an organization’s CSR orientation and its employees’ CSR orientation on employees’ quality of work life. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaduri, G.; Jung, S.; Ha-Brookshire, J.E. Effects of CSR messages on apparel consumers’ Word-of-Mouth: Perceived Corporate Hypocrisy as a Mediator. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2021, 0887302X211055984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsi-bility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, M.; Wilson, T. Building corporate reputation through consumer responses to green new products. J. Brand Manag. 2018, 25, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habel, J.; Schons, L.M.; Alavi, S.; Wieseke, J. Warm glow or extra charge? The ambivalent effect of corporate social respon-sibility activities on customers’ perceived price fairness. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuen, K.F.; Thai, V.V.; Wong, Y.D. Are customers willing to pay for corporate social responsibility? A study of individual-specific mediators. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2016, 27, 912–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, Y. CSR and service brand: The mediating effect of brand identification and moderating effect of service quality. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, L.; Seele, P.; Rademacher, L. Grey zone in—Greenwash out. A review of greenwashing research and implications for the voluntary-mandatory transition of CSR. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TerraChoice. The Seven Sins of Greenwashing; TerraChoice Environmental Marketing Inc.: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, E.L. Green marketing goes negative: The advent of reverse greenwashing. Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2012, 3, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasrodashti, E.K. Explaining brand switching behavior using pull–push–mooring theory and the theory of reasoned action. J. Brand Manag. 2018, 25, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, Z. The dual effects of consumer satisfaction on brand switching intention of sharing apparel. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M.A.; Abrams, D.; Brewer, M.B. Social identity: The role of self in group processes and intergroup relations. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 2017, 20, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klipfel, J.A.; Barclay, A.C.; Bockorny, K.M. Self-Congruity: A determinant of brand personality. J. Mark. Dev. Compet. 2014, 8, 130–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kucuk, S.U. Negative double jeopardy revisited: A longitudinal analysis. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 18, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wagner, T.; Korschun, D.; Troebs, C. Deconstructing corporate hypocrisy: A delineation of its behavioral, moral, and attributional facets. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 114, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; Grace, A.; Palmer, J.; Pham, C. Investigating the direct and indirect effects of corporate hypocrisy and perceived corporate reputation on consumers’ attitudes toward the company. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 37, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; Mitchell, V. The effect of consumer confusion proneness on word of mouth, trust, and customer satisfaction. Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 838–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Grau, S.L.; Garma, R. The new greenwash?: Potential marketing problems with carbon offsets. Int. J. Bus. Stud. 2010, 18, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Chang, C. Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonetti, P.; Maklan, S. Social identification and corporate irresponsibility: A model of stakeholder punitive intentions. Br. J. Manag. 2016, 27, 583–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sudbury-Riley, L.; Kohlbacher, F. Moral avoidance for people and planet: Anti-consumption drivers. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Poon, P.; Huang, G. Corporate ability and corporate social responsibility in a developing country: The role of product involvement. J. Glob. Mark. 2012, 25, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernev, A.; Blair, S. Doing well by doing good: The benevolent halo of corporate social responsibility. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 41, 1412–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.C.; Slotegraaf, R.J.; Chandukala, S.R. Green claims and message frames: How green new products change brand attitude. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Casidy, R.; Yoon, A.; Yoon, S. Brand trust and avoidance following brand crisis: A quasi-experiment on the effect of franchisor statements. J. Brand Manag. 2016, 23, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, S.; Minor, M.S.; Felix, R. The influence of perceived strength of brand origin on willingness to pay more for luxury goods. J. Brand Manag. 2018, 25, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, R.J.; Allen, C.T. Competitive interference effects in consumer memory for advertising: The role of brand familiarity. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).